13

The new analogue

Media archaeology as creative practice in 21st-century audiovisual art

Introduction: retro culture and media

The work discussed in this chapter is part of a trend towards retrospection, where cultural artifacts and aesthetics from previous eras are resurrected and repurposed. This phenomenon can be seen throughout history and is arguably part of human nature. However, this chapter argues that it has been accelerated by (broadcast, recorded, live) media, here discussed particularly with respect to contemporary audiovisual practice.

It positions this as the second part of a cultural revolution brought about by the rise of mass media. The first, associated with the normalization of television as a cultural force during the 1960s and 1970s, fostered an idea of collapsing (geographical) boundaries. This can be seen in the commentary of Marshall McLuhan – in particular his ideas around the ‘global village’ (McLuhan 1964) – and in artworks such as Stan Vanderbeek’s Movie Drome (Vanderbeek 1966) and Nam June Paik and John Godfrey’s Global Groove (Paik and Godfrey 1973).

In the 1980s, the widespread adoption of video recording technology caused a similar collapsing with respect to time, making vast tranches of cinematic history asynchronously available from the nearest video store, and positioning home videos as the first widely available form of user-generated content and personal archives.

The cultural effects of media have been accelerated by the adoption of digital technology, which has made them accessible to the point of ubiquity and collapsed media history to an unprecedented degree. The World Wide Web has made it available, almost in its entirety, at the click of a mouse. One effect of this has been to further encourage the recycling of media in ever more complex and nuanced forms of retro culture.

Although this chapter focuses on the use of analogue technologies implied in its title, it starts its discussion in the proliferation of digital media which this ‘analogue turn’ reacted against. It argues that the combination of analogue and digital techniques is particularly fertile territory for this area of practice, and theorises that a new kind of materiality of sound and light (transcending the duality of analogue or digital) is emerging.

Aesthetics of (digital) failure

Early domestic digital media, such as the CD (brought to market in 1982), were marketed largely on their capabilities for high-fidelity reproduction. In comparison to the analogue media of the time, which were associated with undesirable artifacts, they offered a dream of infinite copy generation, with a copy (or a copy of a copy) being identical to the original.

While digital media were sold as the ultimate destination of ‘hi fi’ development, this was immediately challenged by artists, musicians and other enquiring minds. Their duplicability and ‘perfection’ was seen as a challenge by artists who found methods to subvert media and positively encourage error. Artists such as Yasanao Tone and Oval found ways to ‘wound’ CDs (Tone 1997), a process which would proliferate across other media and define a phenomenon and cultural movement known as Glitch. This can be seen as part of a long tradition of technological subversion in music (technology), including tools and techniques such as vinyl scratching, the prepared piano and the electric guitar. Whilst there was nothing explicitly retrospective in Glitch, it signaled a fallibility, and perhaps humanization, of technology which was to become important to much of the work discussed here. In particular, it established an aesthetic framework where errors highlight qualities unique to a particular medium, and therefore represent the authentic ‘voice’ of that medium in a new kind of materiality. These ideas and others were captured in Kim Cascone’s seminal paper ‘The Aesthetics of Failure: “Post-Digital” Tendencies in Contemporary Computer Music’ (Cascone 2000), which can be seen as an early theoretical touchstone for the field of practice covered here.

Glitch was primarily an audio phenomenon, but Glitch aesthetics filtered through into the visual domain. It can be seen in the visual aesthetics of many music videos made for electronic music producers of the era, for example those directed by Chris Cunningham and Alex Rutterford. Zoetrope, an audiovisual work produced by the author of this chapter in 1998, explicitly attempted to explore an audiovisual aesthetic of failure, ‘use and misuse; abuse, breakdown’ across audio and video (Hyde 1998). More recently, a kind of visual Glitch language has been employed in the datamoshing phenomenon, where low-level software hacks are used to break and subvert the CODECs used by internet video platforms such as YouTube.

Glitch to Hauntology: the analogue turn

The problematisation of digital technology’s perfectionist dream was kindled by the experimentalists of Glitch, but can also be seen in mainstream music production. Here, it centred around a dialogue characterising digital media as alienating and ‘cold’ in comparison to the ‘warm’ qualities perceived in analogue media (and the older recorded material with which it was associated). The origins of this idea can perhaps be found in the crate-digging ethos of early East Coast Hip Hop, and its widespread adoption in the 1980s coincides not only with the rise of digital media, but also the widespread adoption and influence of Hip Hop. This can be seen for example in the career of producer Rick Rubin, who worked with New York–based Hip Hop artists in the early 1980s, had a crossover Rock/Hip Hop hit in Run DMC and Aerosmith’s Walk This Way in 1986, and then went on to work with mainstream Rock, Country and Pop artists such as Johnny Cash and the Red Hot Chili Peppers, taking a pared-back, analogue production approach with him.

In the 1990s, this analogue nostalgia in popular music became more overt. It can be seen in the Trip Hop movement, which exaggerated the retro aesthetics of Hip Hop, highlighting the detritus and noise of (particularly older) technology and the erosion and decay of material, with a kind of melancholic nostalgia in mind. This can be seen in the production style of the British band Portishead, who went to considerable lengths to build these elements into their music, for example cutting material to dubplates and then distressing these records considerably before sampling them (and scratching and cutting them further).

Hip Hop aesthetics can also be seen in the early VJ scene emerging at around the same time. We see a direct equivalent of sampling in the use of ‘plundered’ video loops, and a similar set of aesthetic choices, where old and rare footage is sought after. VJ pioneers such as Hexstatic and Emergency Broadcast Network used audio-visual samples and breakbeats, relying on the cultural resonance of the repurposed material to add a narrative dimension to their work. This idea is taken further in the work of Vicki Bennett (People Like Us), who pioneered a unique kind of audiovisual collage in works such as Story Without End (Bennett 2005), based on old public information films collected in the Prelinger Archive (Figure 13.1).

Figure 13.1 Still from Story Without End, People Like Us.

Electronica duo Boards of Canada explored melancholic aesthetics similar to Trip Hop at around the same time. The elements of their musical language are very different, however, consisting of abstract soundscapes, woozy vintage synths and samples from 1960s information documentaries – the resultant sound is a kind of re-imagination of the work of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop in the 1960s and 1970s. This ‘lost future’ has become a vital force, particularly in the UK. British record label Ghost Box represents this niche prominently – many of their artists (examples being Belbury Poly, Pye Corner Audio and The Advisory Circle) could be characterised as occupying this kind of neo (perhaps alt-) radiophonic territory. The label is represented by a strong visual aesthetic, referencing the artwork of 1960s Penguin paperbacks and children’s Ladybird books and other memorabilia. This aesthetic territory has been explored writ large in the Delaware Road festival, which has had three iterations since 2006, featuring several of these artists. The festival, founded by Alan Gubby and mounted in unusual locations (including a nuclear bunker and a military base), combines retrospective audiovisual aesthetics with pagan imagery, and an occult mythology built around pioneers of the Radiophonic Workshop.

A younger generation of artists are exploring similar ideas but with a more recent set of reference points. Where Boards of Canada (mis)remember the VHS documentaries (with radiophonic soundtracks) they watched in the classroom, artists such as Burial and Zomby take a similar deconstructive and nostalgia-laden approach to the sounds of 1990s pop and dance music. In a parallel development, Vaporwave grew up alongside other niche internet-based genres chillwave and synthwave in the early 2010s. It is somewhat difficult to define, and is perhaps closer to an internet meme, or ‘in joke’ than it is to some of the other areas explored in this chapter. Nonetheless, it is a convenient shorthand for a field of contemporary aesthetics which centres around an ironic appropriation of 1980s and 1990s music styles such as lounge music, smooth jazz and R&B, influenced in particular by mainstream consumer capitalism and advertising, and with a knowing and ironic take on its sources. These musical tropes are often accompanied by visual material that explores similar stylistic territory, emulating 1980s and 1990s video technology and early computer graphics and web design.

A number of artists take a more conceptual approach to the erosion of media with these creative ends in mind. Philip Jeck explicitly (but perhaps prematurely) mourned the death of vinyl records in his seminal Vinyl Requiem (1993), which employed a bank of 180 Dansette Record Players to produce a ‘wall’ of sound in which the signature crackle and hiss of vinyl became more dominant than the music encoded on the records themselves. In works such as Disintegration Loops (2002 onwards), William Basinsky works with tape loops, and runs these loops through reel-to-reel tape recorders until they disintegrate, producing an increasingly ‘broken’ and distorted sound and – eventually – long periods of silence.

These retrospective trends were distilled and defined as Hauntology by Jacques Derrida (Derrida 1993), with this term achieving wider coverage in the 2000s, where writers such as Mark Fisher and Simon Reynolds used it to describe work which explored a ‘nostalgia for lost futures’ (Gallix 2011). Several writers have argued that this type of Hauntology can be seen as a descendent of Glitch (Holmes 2010), exploring the ideas of the latter but in a broader context. Certainly it can be seen that there is a similar concern with the material nature of technologies used in art-making, and how those tools might be deconstructed (sometimes literally).

Maker culture

There is considerable overlap between these aesthetic trends and the ‘maker culture’ which has become widespread in the last decade. One area of activity involves lo-tech modifications to existing hardware, known as Circuit Bending (Ghazala 2005) or Hardware Hacking (Collins 2006). Anyone foregrounding, questioning and subverting technology as a means is likely to be interested in interventions and hacks to this technology, and this approach can clearly be seen as another extension of the ideas behind Glitch.

For the purposes of this chapter we will limit ourselves to a handful of examples, specifically connected with audiovisual practice. One of the simplest and most fundamental subverts the basic electronic signals that comprise analogue audio and video, using a technique sometimes known as Composite Cramming (ibid.). It involves the use of standard definition composite video connections (now essentially obsolete) being cross-wired into the audio domain. Experienced as audio, these signals betray their origins, dominated by the 50Hz (PAL, 60Hz if NTSC) rate of the raster scan on which the TV signal is based, with the finer content of the image manifesting as pseudo-harmonics. Carefully chosen material, often involving repetitive patterns within or between frames, can sometimes yield quite legible audiovisual relationships. The reverse configuration is possible, where audio signals are read as video. However, it is more difficult to produce ‘legible’ results. Any arbitrarily chosen audio signal is likely to yield chaotic, glitchy and noisy material, or indeed nothing at all as the video circuitry might designate it an invalid signal. The author of this chapter’s work End Transmission (Hyde 2009) attempts this, and is built entirely around various composite cramming techniques, working in both directions between audio and video. Additional distortions are produced by transmitting and receiving these signals using short-range UHF transmitters/receivers, in a system where audio and video signals interfere which each other, and even with the movements of the artist while making the work (Figure 13.2).

Figure 13.2

Still from End Transmission, Joseph Hyde.

Working at the low level of composite cramming, it is even possible to ‘mix’ video signals, albeit in a highly unpredictable and unstable way. This can be seen in the ‘dirty video mixer’ circuit designed by Karl Klomp, a very simple circuit capable of interesting if very glitchy results, ideal for building in DIY workshops. Deriving a coherent video image from an audio signal is complex, however, because it relies on synchronisation with the raster of the video display. Such synchronisation is at the heart of analogue video synthesis, which has enjoyed a rebirth in the last decade, based around new tools ranging from the lo-tech to complex and expensive solutions.

Jonas Bers’s CHA/V (Cheap Hacky A/V) project, also the basis for many DIY workshops, allows for simple synchronisation (though it can also function without). This an open source circuit for a simple video synthesiser which can be built with little expert knowledge and minimal expense. One of the key advantages of this circuit is that it is built around an existing device – a VGA signal generator. These are widely available and at minimal expense, so that a CHA/V video synthesiser can be built for under $10 at current prices. Another, slightly more expensive, device is the Synchronator, designed by Bas van Koolwijk and Gert-Jan Prins. The Synchronator simply adds video synchronisation and colour signals to an audio signal (with no other controls) to allow audio signals to be passed into the video domain with reasonable image stability. A companion device, the ColorControl, allows further control over colour (hue and saturation), and an HD version of the Synchronator is offered alongside the standard SD model. Another approach is offered by Netherlands-based artist Gijs Gieskes. Gieskes has designed a number of circuits for video production and manipulation (alongside many for audio and other purposes). Of particular note is the 3TrinsRGB+1 device, which represents a fairly fully featured video synthesiser at a price point below anything comparable. This device is available in various forms – Gieskes himself supplies PCBs and full kits for home builds, where various third parties offer fully built solutions.

Modular systems

Much of the work discussed in the previous section relies on a ‘hacker’ approach, and the willingness of artists to build – or rebuild – their tools. This has offered an alternative to the ‘black boxes’ represented by commercial software and hardware, but there is room between these two poles. In the late 1990s, new areas of technology development offered a more modular approach, where building blocks could be assembled into bespoke systems without the need to wield a soldering iron or write code. This can be seen in computing in the emergence of ‘physical computing’ platforms such as the Arduino and modular coding environments such as Max/MSP and puredata, all of which have a place in contemporary AV practice.

Perhaps the most striking example can be seen in the re-emergence of modular synthesisers, and the establishment of the Eurorack standard, defined by Doepfer Musikelektronik in 1996. The latter is important because it allowed a huge explosion in this area, and a new approach: where in the modular synthesisers of the 1960s and 1970s, the modules making up such a synthesiser would generally be produced by one manufacturer (by necessity, in the absence of any standard), Eurorack allowed users to build bespoke instruments out of modules from a variety of companies. More importantly, it fostered the emergence of ‘boutique’ manufacturers, who might produce only one or two very specialised or idiosyncratic modules. It involved the musician directly in the design of their own instrument, and offered opportunities for a DIY approach (with many modules available as build-your-own kits, or open-source schematics).

The new modular synthesiser rapidly made an impact on the visual domain too. Alongside the emergence of companies making small-run audio modules, a number of manufactures have started to make modules for video synthesis. The most prominent of these is LZX Industries, founded by Lars Larsen (US) and Ed Leckie (Australia) in 2008 and now based in Portland, Oregon. The company produces stand-alone video synthesis units such as the Vidiot, but is perhaps best known for its video synthesis modules. It makes a wide variety of such modules, covering most aspects of video synthesis, venturing into other areas such as laser control (through its Cyclops module), and including a large range of DIY modules in its Cadet range.

Perhaps most importantly, it has established a standard for video synthesis modules. This format is similar in many ways to the Eurorack standard – the physical specification is identical, and while the electronic specification is not, it is fairly easy to mix Eurorack and LZX-standard modules, and to convert control signals (where necessary) from one standard to the other.

A number of other manufacturers (or individuals) are worth mentioning here. Nick Ceontea, operating as brownshoesonly, offers a small number of modules designed to the LZX specification. Video synthesis pioneer Dave Jones is working towards a full video synthesiser system, but in the meantime produces the MVIP module. Unlike the LZX series, this module is designed with Eurorack-format control voltages in mind, and is essentially offered as a stand-alone solution to add video functionality to a Eurorack system.

A number of communities have grown up around these instruments and systems. These were first established in the US, where the Experimental Television Centre grew out of the media access programme founded by Ralph Hocking at Binghamton University in 1969, and moved to Owego, New York in 1971. The ETC was responsible for the development of many early video tools such as the Paik/Abe Video Synthesizer, the Rutt/Etra Scan Processor, and a suite of tools built by Dave Jones, and hosted video artists such as Steiner and Woody Vasulka, Gary Hill and Shigeto Kubota (High et al. 2014). The ETC wound up its residency programme in 2011, but Signal Culture, also housed in Owego, continues to offer facilities to artists, including some of the same tools.

The UK also has a long history of such communities, such as London Video Arts, which was founded in 1976 and (after a number of changes of name and focus) merged with the London Film-Makers Co-op in the late 1990s to eventually become LUX in 2002. A more recently founded community, Video Circuits, run by Chris King first as a blog and now as a Facebook group brings together some of the pioneers of analogue video with many younger practitioners. It is currently the most active such group online, with over 7,000 members at the time of writing.

Cracked ray tubes

Some of the interest in analogue video is wrapped up in the unique aesthetics of the cathode ray tube, and methods to hack or ‘crack’ (Kelly 2009) this technology. This can be seen in parallel to video synthesis in historical terms, with video art pioneer Nam June Paik (for example) as interested in the aesthetics of television sets themselves as the images they display.

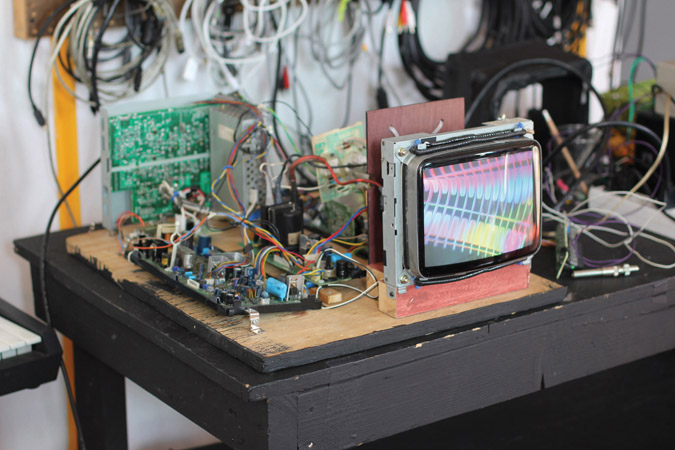

The hacking affordances of TVs are somewhat limited, however, due to the complexity of the imaging process. Images are formed by means of a raster scan, where an electron beam is electrostatically deflected to form a synchronised pattern of scan lines. The Raster Manipulation Unit, colloquially known as the Wobbulator, developed by Paik with Shuya Abe in 1968, built on Paik’s earlier experiments with magnets, and employs copper wire coils wound around the cathode ray tube of a black-and-white TV to further deflect and distort the scanned image. This is a fairly involved, and indeed dangerous process (due to the high voltages involved), but several contemporary versions of the device have been built. One is at Signal Culture, where Jason Bernagozzi and Dave Jones also developed a version based on a colour TV (Figure 13.3).

Figure 13.3

The Colour Wobbulator at Signal Culture.

Source: Photo: Joseph Hyde.

Working as Cracked Ray Tube, James Connolly and Kyle Evans ‘explore the latent materiality of analog cathode ray tube televisions and computer monitors’ shared using an open ‘maker culture’ approach based on video tutorials and hands-on workshops. One of their tutorials allows the raster scan of a TV to be bypassed. It effectively turns a raster-based TV into a vector monitor, where the horizontal and vertical positions of the electron beam are arbitrary and can be directly controlled using variable voltages, or indeed audio, making it much more open in terms of creative misuse. Vector monitors are most commonly found in oscilloscopes and have been used for ‘oscilloscope music’, or ‘oscillographics’ since the 1950s, when Mary Ellen Bute developed a kind of lexicon for aesthetic visual representations of sound in works such as Abstronic (Bute 1952). During the 1960s and 1970s, oscillographics was a regular mainstay of popular electronics magazines. Its current resurgence includes the work of Australian artist Robin Fox, whose oscilloscope-based DVD ‘Backscatter’ was released in 2004. It arguably hit the mainstream through the work of Jerobeam Fenderson, whose YouTube videos went close to ‘going viral’ in 2014. A set of techniques for this practice has been defined by Derek Holzer (Holzer 2019), who has also been instrumental, with Ivan Marušić Klif and Chris King, in producing the Vector Hack festival centred on this practice.

A particularly vibrant hacker ‘scene’ has grown up around the GCE/MB Games Vectrex videogame console. The Vectrex, commercially available only from 1982 to 1984 and not commercially successful, is the only domestic video console to be based around a vector display. Its design is a clear digital/analogue hybrid, with one circuit board built around a microprocessor to run the game software, and one based on analogue circuits to drive the CRT display. The two boards are connected by three control voltages, controlling the X (horizontal deflection), Y (vertical deflection) and Z (brightness) of the electron beam. A simple hack is therefore possible, by means of disconnecting these signals and substituting others. Within certain constraints, audio works well, allowing the Vectrex to be used as a kind of oscilloscope, but with an image quality all of its own. This practice, established by Lars Larsen (based on earlier experiments with the console within the gaming community) in 2012, has become a mainstay of the Vector Synthesis community and has been well documented by Andrew Duff (an example of Duff’s work with the Vectrex can be seen in Figure 13.4).

Figure 13.4

Vectrex Performance System v.1 – Andrew Duff

Source: Duff 2019.

Light and sound materiality

The dialogue between analogue and digital, and the focus on technology implied therein, has perhaps run its course. In the 21st century, we see a new interest in working with sound and light as physical materials as opposed to electronic signals or media. We can observe a resurgence in sound art which explores physical space and acoustic phenomena. We can also see an equivalent burgeoning interest in the materiality of light.

Light has been explored through tantalising experiments in Colour Music and Lumia for centuries, and of course has always played a role supporting music and theatrical performances. Its use achieved a breakthrough in the context of the 1960s psychedelic movement, and the evolution of the light shows that accompanied performances by the biggest bands of the era, such as The Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane and Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention. These performances usually involved an overhead projector, and a set of interventions on the beam of this projector (typically involving glass containers and coloured liquids of various kinds) operated in real time to produce the lightshow. Artists producing such light shows included Glenn McKay, Elias Romero and Joshua White and the Single Wing Turquoise Bird collective.

This area of practice has maintained a continuous existence, and although it was perhaps overshadowed by other means of audiovisual production for several decades, it has had a renaissance in recent years. This continuity, and resurgence, has been fostered by the Psychedelic Light Show Preservation Society, an online community now based on a Facebook group (founded by Donovan Drummond and previously centred around various other communities off- and on-line). This community facilitates a connection between younger artists engaging with the area for the first time and those who pioneered this practice in the first place. Several key figures from the early days of the psychedelic light show are active contributors to the group, such as Joshua White. As well as contributing to the community through groups such as this, White (as an example) continues to actively perform, building on his work with the giants of 1960s psychedelic music with performances with contemporary bands such as MGMT (Figure 13.5).

Figure 13.5 Joshua light show with MGMT 2002.

Source: Photo: Stan Schnier.

There are many younger artists turning to this way of working. Others are using similar ideas about light as a fluid, architectural entity in other contexts. Kathrin Bethge extends classic liquid light show techniques for use in large-scale outdoor installations and as part of theatre and dance productions (she also performs as part of several audiovisual ensembles with leading contemporary musicians). Mark Weber, aka MFO, works across a similarly broad range of contexts. He combines some of the techniques of the liquid light show with digital tools, and his work generally explores light as a volumetric and immersive element as opposed to a projection (onto a surface). An example of this is his light show for Australian producer Ben Frost’s A U R O R A tour, and his work as Director for Lights and Visuals of Berlin’s Atonal festival has helped establish this kind of practice as a vital force in contemporary audiovisual performance.

A natural extension of the practice employed in Vector Synthesis is the use of lasers, usually in the form of ILDA (International Laser Display Association) specification RGB laser projectors. Such laser projectors cannot be described as obsolete technology – indeed they are in a somewhat febrile period of development where improved diode-based technologies are driving up the power and brightness of the beams while driving down the size and cost of projectors. The use of lasers, usually using specialist laser control software, is somewhat ubiquitous in large-scale live music productions. This type of practice achieves a high level in the work of high-profile groups such as the Laserium (operating in one form or another for 45 years) and Marshmallow Laser Feast. However, for the purposes of this chapter, only those taking a more hauntological, or ‘cracked media’ approach are discussed here.

With associations with 1980s clubs and 1990s raves, lasers are seen by some as having a somewhat retro quality, and some artists exploit this. Italian producer Lorenzo Senni’s recent work is characterised by Senni as ‘pointillistic trance’ or ‘rave voyeurism’. It deconstructs the euphoric highs of trance, house and rave music, and the use of lasers in his live shows references their (over)use in this context.

Others are finding ways of using laser projectors that are determinedly ‘lo fi’ and analogue. The ILDA spec includes a standardised 25-pin D-Sub connector which allows the external control of beam deflection and (colour) intensity. Although this is designed for connection to a PC, and to allow control of the laser by sophisticated software solutions (such as those offered by laser manufacture Pangolin), the actual interface technology is entirely analogue. It is therefore possible to bypass the use of existing laser control software and control the projector (x and y deflection of the beam, intensity of RGB beams) using analogue voltages. Within certain constraints (largely frequency bandwidth), audio signals can directly be used for this purpose, in a process similar to that employed in oscillographics.

Robin Fox, mentioned earlier, evolved his practice from oscillographics to the use of lasers in 2007. He has continued to explore a direct connection between sound and lasers in works such as Single Origin Laser (2018). Alberto Novello, aka JesterN, is an Italian scientist, composer and media artist. He is well known for his work with analogue audio synthesis, where he works as a solo artist and with senior figures in the field such as Alvin Lucier, Evan Parker and Trevor Wishart. His current work Laser Drawing (Figure 13.6) is again a development of earlier work using vector monitors, in this case the Vectrex.

Figure 13.6

Alberto Novello’s Laser Drawing.

Source: Photo: Erin McKinney.

Robert Henke’s work using these techniques is particularly technically advanced. Although the lasers he uses in installation works such as Fragile Territories and performances such as the Lumière series are computer controlled, the software he uses is entirely self-built around Max/MSP and Ableton Live. The signals produced by the software are entirely in the audio domain and communications with the laser projector use analogue ILDA connectors, a potent combination of analogue and digital. Recently, Henke has also explored the structural properties of laser radiation. Phosphor uses an ultraviolet laser (invisible to the naked eye) and phosphor dust, with the laser leaving a ‘trace of light’ in the phosphor, which slowly erodes over time. Deep Web, with Christopher Bauder, combines lasers with a large kinetic sculpture in an environment which is exhibited both as an installation and performance space.

Cinematic practice

It is beyond the scope of this chapter to discuss the world of cinema in general, but where it intersects with this renewed interest in the materiality of light (and sound) we can also find an undercurrent of Hauntology. The Structural Film movement of the 1960s and 1970s represented filmmakers becoming acutely concerned with the precise and unique qualities of their medium, as epitomised by perhaps the first structuralist film, Tony Conrad’s The Flicker (Conrad 1965). Four years later in 1969, Ken Jacobs produced his best-known film, Tom, Tom the Piper’s Son (Jacobs 1969), in which a short 1905 Biograph film is endlessly re-photographed. Of particular interest for our discussion is what Jacobs writes about it: ‘Ghosts! Cine-recordings of the vivacious doings of persons long dead. Preservation of their memory ceases at the edges of the frame’.

More recently, New York–based filmmaker Bill Morrison has built an explicitly hauntological cinematic language through the use of archival film footage, which he often edits to contemporary music by well-known composers (including fellow New Yorkers Steve Reich, Philip Glass and Michael Gordon). Often he makes a particular feature of film stock which has decayed, a well-known example (with music by Michael Gordon) being his 2002 feature-length film Decasia (Morrison 2002).

As well as the medium itself, we see artists exploring older cinematic techniques such as stop-frame animation. An example of this can be seen in the work of Hong Kong–based artist Max Hattler. His early works such as AANAATT (Hattler 2008) re-imagine stop-motion animation for a 21st-century context and make a knowing and deconstructed approach to the medium. Johan Rijpma brings stop-frame animation to the texture and chaos of the real world, capturing in a phenomenological way patterns of evaporating water (Rijpma 2014b) or breaking ceramics (Rijpma 2014a). More explicitly linked to an audiovisual dialogue is Noise, by Kasia Kijek and Przemek Adamski (Kijek and Adamski 2011), a ‘game of imagination provoked by sound’ and ‘the basics of synaesthetic perception’, where sounds are represented in the visual domain by animated objects.

Other artists explore cinematic illusions that predate celluloid film. There are a number of re-inventions of the zoetrope, perhaps the most spectacular being Matt Collishaw’s All Things Fall (Collishaw 2015), which uses a large-scale 3D printed sculpture to generate its effect. Jim LeFevre uses similar techniques (and coins the term ‘phonotrope’), and makes use of carefully constructed 2D and 3D disks which can be played on a record turntable, extending this practice in interesting ways – for instance working with a potter to produce functional ceramics which also work as phonotropes. British audiovisual duo Sculpture work within a strongly hauntological aesthetic which makes heavy use of tape loops and delays. Their visuals are primarily based on zoetrope (or phonotrope) disks, which are controlled live by Reuben Sutherland to psychedelic effect (Figure 13.7). They have also released picture disks that function both as phonotrope and audio record, such as Form Foam (Hayhurst and Sutherland 2016).

Figure 13.7

Sculpture performance with phototrope disk.

One technique of particular relevance to our audiovisual discussion is Direct Sound, sometimes known as Synthetic Sound. This is a technique specific to celluloid film, with direct parallels with ‘Composite Cramming’ (discussed earlier). It offers a similarly literal approach to audiovisual relationships, where a signal intended for one sense (sight or hearing) is experienced or interacted with using the other. In this case, the ‘signal’ is the optical soundtrack of celluloid film.

Optical sound was introduced in the 1920s, gradually displaced from mainstream usage by the magnetic soundtrack from the 1950s to the 1970s, but still in use today. Perhaps because an optical soundtrack is visible to the naked eye, ‘hacking’ this technology has proved irresistible to audiovisual artists since its inception. Many of the early pioneers of Visual Music, including Oskar Fischinger, Norman McLaren and the Whitney brothers, found inventive ways of manipulating or ‘synthesising’ an optical soundtrack. This technique might be considered a core part of the repertoire of structural cinema through the 1960s and 1970s, as exemplified in the work of Guy Sherwin and Lis Rhodes. It has enjoyed a continued existence and can be seen in more recent films such as Steve Woloshen’s Visual Music for Ten Voices (Woloshen 2011) and Richard Reeves’s Linear Dreams (Reeves 1997). It has formed a key part of the work of Bristol Experimental Expanded Film (BEEF), founded in 2015, who foregrounded it in their event The Brunswick Light Ray Process in 2017.

Similar techniques have been used removed from cinematic projection. There is a particularly strong tradition in this area in Russia, covered in depth in Andrey Smirnov’s book Sound in Z: Experiments in Sound and Electronic Music (Smirnov 2013). Another example is the remarkable Oramics machine originally developed by Daphne Oram (founder of the Radiophonic Workshop) in 1957. This device was a synthesiser where the user input was via drawings made on multiple strips of film. In 2011, this work received a revival of interest around the exhibition Oramics to Electronica in London’s Science Museum. This interest extended to an attempt to restore the machine. Although this was ultimately unsuccessful, it led Tom Richards to develop his Mini Oramics machine, completed in 2016 and built in accordance with Oram’s never-realised plans for a portable version of her device.

Conclusion: media (as) archaeology

This kind of practice can perhaps be seen as part of a broader discourse around media archaeology, which ‘excavate[s] the past in order to understand the present and the future’ (Parikka 2012: 2), and in particular views ‘the new and the old in parallel lines’ (ibid.), in the kind of temporal collapse discussed in the introduction to this chapter.

This taps into some of the most important sociological and environmental issues of the present day. Increasingly, the idea of technology as representing ‘progress’ has been cast into doubt, and deepening awareness around the climate emergency has been causing many to question the expansionist capitalist ethos it is built on. Recently, many artists working with technology have started to question the sustainability and impact of their technology usage. Where the central narrative of technological development was seen in somewhat utopian terms, people are increasingly aware of its negative societal and environmental impacts. All these concerns make the recycling of technology attractive beyond purely aesthetic value, and are likely to see more and more artists incorporating this approach into their practice.

Bibliography

- Barbrook, R. (2007) Imaginary Futures: From Thinking Machines to the Global Village. London: Pluto.

- Benjamin, W. (1992 [1934]) The Author as Producer. In: W. Jennings (ed.), R. Livingstone (trans.) Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, Volume 2 (1927–1934). Belknap Press of Harvard University. pp. 768–782.

- Bennett, V. (2005) Story without End. Available online: www.ubu.com/film/plu_story.html [Accessed 15/11/19].

- Bute, M.E. (1952) Abstronic. On Visual Music from the CVM Archive, 1947–1986 (DVD). Center for Visual Music, 2017.

- Cascone, K. (2000) The Aesthetics of Failure. Computer Music Journal. 24(4). pp. 12–18.

- Collins, C. (2006) Handmade Electronic Music. Abingdon and Oxon: Routledge.

- Collishaw, M. (2015) All Things Fall. Available online: https://vimeo.com/125791075 [Accessed 15/11/19].

- Connolly, J.; Evans, K. (2014) Cracking Ray Tubes: Reanimating Analog Video in a Digital Context. Leonardo Music Journal. 24. pp. 53–56.

- Conrad, T. (1965) The Flicker. Distributed by LUX. Available online: https://lux.org.uk/work/the-flicker [Accessed 15/11/19].

- Derrida, D. (1993) Spectres of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning, and the New International. New York: Routledge.

- Duff, A. (2019) Vectrex 3 X Inputs For X/Y/Z Oscillographics Modification v2. In J. Bernagozzi (ed.) The Signal Culture Yearbook. New York: Signal Culture.

- Fisher, M. (2012) What Is Hauntology?. Film Quarterly (Vol. 66/1). Oakland: University of California Press.

- Gallix, A. (2011) Hauntology: A Not-So-New Critical Manifestation. London: The Guardian, 17 June.

- Ghazala, R. (2005) Circuit-Bending: Build Your Own Alien Instruments. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Hattler, M. (2008) AANAATT. Available online: https://vimeo.com/27808714 [Accessed 15/11/19].

- Hayhurst, D.; Sutherland, R. (2016) Form Foam. Available online: https://vimeo.com/192017698 [Accessed 15/11/19].

- High, K.; Hocking, S.M.; Jimanez, M. (2014) The Emergence of Video Processing Tools: Television Becoming Unglued. Bristol: Intellect.

- Holmes, E. (2010) Strange Reality: Glitches and Uncanny Play. Eludamos Journal for Computer Game Culture. 4(2). pp. 255–276.

- Holzer, D. (2019) Vector Synthesis: A Media Archeological Investigation into Sound-Modulated Light. Helsinki: Self-Published.

- Hyde, J. (1998) Zoetrope. Distributed by LUX. Available online: https://lux.org.uk/work/zoetrope [Accessed 15/11/19].

- Hyde, J. (2009) End Transmission. Available online: https://vimeo.com/3241660 [Accessed 15/11/19].

- Jacobs, K. (1969) Tom, Tom the Piper’s Son (video). Distributed by Electronic Arts Intermix. Available online: www.eai.org/titles/tom-tom-the-piper-s-son [Accessed 15/11/19].

- Kelly, C. (2009) Cracked Media: The Sound of Malfunction. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Kijek, K.; Adamski, P. (2011) Noise. Available online: https://vimeo.com/21154287 [Accessed 15/11/19].

- McLuhan, M. (1964) Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Morrison, B. (2002) Decasia. HD Stream Rented. Available online: www.amazon.com [Accessed 01/11/19].

- Paik, N.J.; Godfrey, J. (1973) Global Groove. Distributed by Electronic Arts Intermix. Available online: www.eai.org/titles/global-groove [Accessed 15/11/19].

- Parikka, J. (2012) What Is Media Archaeology? Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Reeves, R. (1997) Linear Dreams. Available online: www.youtube.com/watch?v=vEvW-tHVhvg [Accessed 15/11/19].

- Rijpma, J. (2014a) Descent. Available online: https://vimeo.com/92009557 [Accessed 15/11/19].

- Rijpma, J. (2014b) Refreshment. Available online: https://vimeo.com/87478840 [Accessed 15/11/19].

- Smirnov, A. (2013) Sound in Z: Experiments in Sound and Electronic Music. Cologne: Walther Konig.

- Tone, Y. (1997) Solo for Wounded CD. (CD). Tzadik Records, Cat. #7212.

- Vanderbeek, S. (1966) Culture Intercom, a Proposal and Manifesto. Film Culture. 40. pp. 15–18, reprinted in Battcock, G. (1967) The New American Cinema: A Critical Anthology. New York: Dutton. pp. 173–179.

- Woloshen, S. (2011) Visual Music for Ten Voices. Available online: https://vimeo.com/20343694 [Accessed 15/11/19].