24

Audiovisual heterophony

A musical reading of Walter Ruttmann’s film Lichtspiel Opus 3 (1924)

Introduction

In this chapter I discuss my new musical score for Walter Ruttmann’s short, abstract film Lichtspiel Opus 3 (1924), composed in 2014. During the first section I consider Ruttmann’s artistic background and relationship to his peers, Hans Richter and Viking Eggeling. The film’s spatio-temporal characteristics and inner relationships are closely scrutinised. Overall, Ruttmann avoids montage in favour of a more evolutionary, evenly proportioned time character; meanwhile, the choreographic elements, varied repetitions, strong formal contrasts and fluid rhythmic patterns all appear to spring from the same structural impulse as music. I wanted to use a ‘musical’ reading of the film images as the starting point for a score which functioned as a marker of the film’s ‘musicality’. Initially, however, I was unsure of how to practically realise this ‘analytical’ ideal without lapsing into sterility and slavish predictability. My compositional approach was ultimately enriched and transformed through stimulating, productive encounters with the multimedia theories of Nicholas Cook and the music of Conlon Nancarrow, in which contrasting layers of rhythmic activity are clearly discernible, almost like a musical ‘split screen’ effect. Subsequently, I developed a research method for interrogating and ‘performing’ Ruttmann’s abstract film text musically, by reading it as a set of musical instructions, or ‘score’. This formed the starting point and material basis for a multi-faceted, polyphonic musical response, which illuminates formal detail and structure while simultaneously contributing additional layers of movement and meaning. The in-depth audiovisual analysis in the third section presents detailed case studies from the film and score. The chapter ends with some further reflections on the project; the overall approach is defined as ‘audiovisual heterophony’.

Walter Ruttmann and the spatio-temporal characteristics of Lichtspiel Opus 3

Many abstract (non-narrative, non-representational) films from the silent era claim an analogy with music. German animations such as Rhythmus 21 (Hans Richter 1921/4), Symphonie Diagonale (Viking Eggeling 1924), and Lichtspiel Opus 3 (Walter Ruttmann 1924) reject montage, in favour of spatial subdivisions and a ‘polyphony’ of visual elements. Hans Richter and Viking Eggeling sought to use musical processes and forms as purely technical models, for plotting and co-ordinating simultaneous visual movements over time, with every action ‘producing a corresponding reaction’ (Richter 1957: 64). By contrast, Ruttmann was a more ‘emotive’ artist and less of a theorising personality. However, he was an accomplished cellist, having studied music as well as visual art at the Academy of Fine Arts, Munich, and the influence of Kandinsky can be clearly discerned in his mode of painterly abstraction. His first film, Lichtspiel Opus I, is probably the earliest surviving example of abstract cinema, resembling as it does a painting in motion (Elder 2008: 120). The work has also been likened to a dance choreography.1 However, Richter was critical of the work’s impressionistic tendencies (Richter 1949: 222–223) and another contemporary reviewer commented on its ‘troubling bent towards cuteness’ (Elder 2008: 124). While movements are controlled in an assured and ‘professional’ manner, gestures are often not particularly interrelated or differentiated. The later films in Ruttmann’s Opus series are more aesthetically accomplished and structurally sophisticated, with dynamic contrasts between different types of shapes and movement occurring amid ‘stark architecture’ and ‘complex musical structures’ (Elder 2008: 124). Ruttmann pulled stylistically closer to his peers without sacrificing his spontaneity, verve and slicker animation style.

Overall, the formal time-structure of Lichtspiel Opus 3 is repetitious and very sectional, demonstrating Ruttmann’s apparent concern for periodicity and corresponding units of similar duration. The film has an ‘organic’ unity akin to composed music, as visual gestures and sequences are recalled and transformed throughout. Ruttmann often subdivides the screen like a grid; forms and movements are arranged diagonally, layered, grow, merge, break apart and reciprocate one another in many sequences. However, these visual elements are more than merely functional units, unlike the slowly oscillating rectangular components in Rhythmus 21 (Lawder 1975: 52). Put simply, the forms and movements have a strong aesthetic significance and identity in and of themselves; Ruttmann allows them a degree of autonomy as they ‘dance’. Furthermore colour plays an important structural role in Lichtspiel Opus 3, providing additional differentiation between forms and movements; it is used as ‘an element in choreography, almost like stage lighting’ and there are even black ‘visual silences’ (Moritz 1997). Both these features also help to reinforce the film’s large-scale sectional symmetries and contrasts.

Symphonie Diagonale has been characterised as the visual embodiment of a sonata form.2 I find this particular musical reading of the film’s time structure problematic; the formal contrasts between hard, angular elements and softer, curved lines are too subtle. The static, muted animation style (Le Grice 1977: 24) and lack of colour give the film a continuous, unbroken quality, particularly when viewed silently (as intended by Eggeling). This, along with the film’s intricate, interrelated, ‘imitative’ style of textural patterning surely places it aesthetically closer to the ‘seamless, almost uniform flow’ of Baroque music (Rosen 1971: 43) and certain forms of atonal modernism (e.g. Webern) than to a Classical-Romantic aesthetic. By comparison, the formal contrasts in Lichtspiel Opus 3 are much more clearly and dramatically presented, with conflicts between geometric and curved forms and between pumping ‘pistons’ and smoother gestures particularly prominent. As mentioned previously, the use of colour and visual ‘silences’ prevent the overall pacing from becoming too uniform. There are no sequences featuring curved forms until about a third of the way through the film (1’18.7”) and these are mostly kept separate from the geometric, modernistic elements and ‘aggressive’ movements until the fast closing section (from about 2’59.0” to 3’20.0”). This is a vivid formal climax, in which many of the earlier forms and sequences are recalled and forcefully merged into one another, with rapid bursts of visual activity and densely layered shot compositions.

Lichtspiel Opus 3 is especially notable for its rhythmic freeness and fluidity, which also contributes a great deal of energy and drama to the visual processes.3 There are two possible ‘musical’ readings of this phenomenon, a ‘romantic’ and a ‘modernist’ one. The fluidity can be interpreted as a form of ‘rubato’ (flexible interpretations of the beat), found mainly in performances of Classical and Romantic music. Alternatively, it can be read as a series of written-out rhythmic accelerations and decelerations, relating to modernist techniques of musical composition. The former would seem to accord more with other elements in the film (the interaction of two ‘themes’, the apparent concern for corresponding units of similar duration) and in all probability is what Ruttmann was consciously emulating. However, the latter suggests a rhythm fixed in time and utilised as part of the compositional structure, as opposed to an improvisatory feature added on afterwards by a performer for purely expressive purposes; therefore, it is a more appropriate and useful analogy, regardless of Ruttmann’s intentions.

From a ‘musical’ reading of the images to a multi-faceted compositional approach

The main compositional research questions which arose at this stage were these: if the spatio-temporal characteristics of Lichtspiel Opus 3 show evidence of having been systematically modelled after musical processes and forms, can I develop a method for interrogating the film musically and learn more about this phenomenon through the act of musical composition? How might a new musical soundtrack function as a marker of the film’s ‘musicality’, ‘analysing’ and commenting on the images while, at the same time, functioning as a multi-faceted musical composition, avoiding sterility and slavish predictability? In Analysing Musical Multimedia, Nicholas Cook argues that similarity is the starting point for a ‘transfer of attributes’ between two media, especially music and film. Meaning is created from a ‘limited intersection of attributes’, not ‘complete overlap or total divergence’ (Cook 1998: 81–82). Seeking to formulate and test new analytical strategies, he also makes a striking analogy between the interaction of musical elements (like pitches, rhythms) and the perceptual interaction between individual components in multimedia (Cook 1998: 24).

While it is possible to conceive of certain time-based notions, particularly ‘rhythm’ and ‘counterpoint’ functioning in a broadly similar way across different media, obviously musical and abstract film processes cannot be measured by exactly the same standards, and subject to precisely the same criteria in practice; there will always be subtle perceptual and behavioural differences, which intrude. However, it is at least theoretically possible to envisage an intricate audiovisual fabric, in which there are not only significant ‘internal’ relationships within each separate medium (i.e. between pitch and rhythmic material, or visual forms and motion) but also meaningful connections and interactions between pitch and visual forms, rhythm and visual motion, musical texture and visual shot composition and so on. Over time, relationships between these elements may be set up and subsequently changed, or even abandoned; nothing stays fixed by necessity or design. Given that the most significant aesthetic, structural and behavioural characteristics of Lichtspiel Opus 3 include spatial subdivisions, the ‘polyphony’ of visual elements (overlapping, interrelated and reciprocal movements), varied repetition, formal contrasts between ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ elements and a fluid approach to rhythm, I determined that ideally the music should seek to emulate these characteristics as far as possible without compromising its own structural integrity. However, it should also contribute additional layers of movement and meaning, enriching and enlivening the audiovisual texture, without expressively overwhelming the film. Reconciling these competing objectives represented the main technical challenge of the project.

As I searched for a flexible, rhythmic, dynamic musical style with roomy textures, capable of accommodating and articulating multiple musical perspectives without becoming weighed down by them, I found myself drawn to the music of Nancarrow. In Nancarrow’s player piano studies, time is ‘manipulated into something that can exist in multiple ways at once’ (Murcott 2012: 2). This is particularly apparent in a piece like Study No. 21 (also known as ‘Canon X’). The apparently simple combination of an accelerating lower line and decelerating upper line creates a highly distinctive and uncannily powerful effect. There is an air of permanent flux, of formal imbalance and unresolved tension. Temporal ambiguity dominates the entire piece; it is impossible to ‘reconcile’ the two separate layers of activity, or determine a ‘central’ pulse. Most importantly for my purposes, the fast, busy texture allows room for contrasting musical materials to operate simultaneously, in a clearly audible way; there are multiple ‘points of entry’ for the listener. The organisation of the musical texture is perhaps analogous to a split-screen effect.

There are a number of additional characteristics which make this style of music aesthetically appropriate for my purposes. Firstly, a piece for player piano (or electronic sequencer/MIDI) can execute impossibly fast rhythms and agile melodic runs, meaning that it has the potential to keep pace with and ‘catch’ rapid visual patterns very precisely. During a discussion on Nancarrow’s player piano studies, Paul Griffiths refers to the ‘joys and comedies of heavy loads lightly carried’, explicitly linking this phenomenon to cartoons and animation more generally (Griffiths 1995: 101–102). Secondly, while the textures in many of the player piano studies are full of elaborate pitch patterning and harmonic dissonance is by no means avoided, the fast tempi and predominance of percussive, staccato attacks mean that the perceptual focus generally shifts from the vertical to the horizontal. The music is not typically weighed down by dense, introspective harmonic activity; much of it ‘moves too quickly for harmony to register’ (Gann 1995: 12). Instead, Nancarrow almost always foregrounds rhythm and polyphony; these are elements which are intrinsically musical, but less exclusive to music than harmony and pitch functions. By way of illustration, the overlapping, rapidly ‘echoing’ visual flourishes and fluid visual rhythms which occur in Lichtspiel Opus 3 could be regarded as a very approximate visual analogue of his imitative textures and irregular rhythmic patterning. Finally, while Nancarrow’s work is abrasively modernist in many ways, it does not completely reject the past. The composer often relied on an ancient device (canon) in order to produce his futuristic-sounding musical textures (Gann 1995: 109). He also restricted himself to the 12-note equally tempered scale and a percussive piano timbre. The player piano studies often feature pulsating materials, developmental structures and even triads (although obviously these elements are abstracted and divorced from their usual context).

I sought to apply similar techniques in an audiovisual context, assembling a multi-faceted musical commentary which draws attention to and meaningfully interprets the spatial subdivisions, polyphony of visual elements and fluid visual rhythms of Lichtspiel Opus 3. I began by treating the visual patterns as a set of instructions, or ‘score’, which I ‘performed’ by composing a fragmentary single line of music, meticulously subordinated and synchronised to the picture with the aid of a click-track. I tried to ‘catch’ as many visual details as possible. This very close, imitative reading was subsequently transformed, becoming the structural bedrock and material basis for a multi-faceted, polyphonic musical response. The finished piece seeks to illuminate detail and articulate structure, for example through shadowing, punctuation and temporal partitioning. However, there are also layers which intensify, even exaggerate visual gestures, superimpose additional rhythmic complexity and move at their own pace. This technique facilitated maximum compositional control, while maintaining contact with the picture at all times and enabled the conception of a flexible formal outline at an early stage in the compositional process.4

The instrumentation features a combination of live performers (piano, vibra-phone) with pre-recorded electronic audio parts (sampled piano, harpsichord sounds). Both performers receive a click-track via headphones and the electronic parts are routed through loudspeakers. The electronic (MIDI) parts help to lock in the choreographic, synchronised gestures more tightly than human instrumentalists would be able to by themselves. They also ensure that the complexity of the musical rhythms and their sometimes confrontational relationship with the picture are intensified rather than softened. While the music has an improvisatory, humorous sensibility, with allusions to jazz rhythms and a ‘waltz’ figure in the middle section, the end result is nervously playful rather than ‘pretty’. Musical patterns originally prompted by the visuals are gradually reworked according to their own, independent logic and woven back into the semi-autonomous polyphonic fabric of the music.

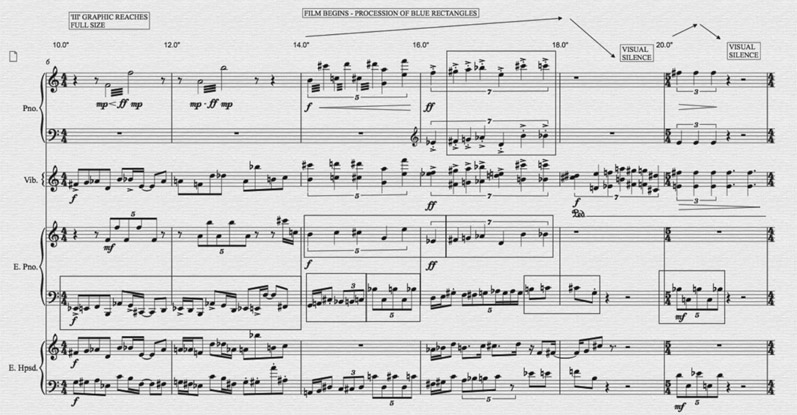

Pitch centres are important, strengthening musical unity and directionality. However, there is an increased concern with melodic variation – melodic patterns are constantly fragmented and inwardly re-shaped, which invites the viewer to examine the images more critically, drawing attention to transformations which occur within them. The bassline in the first two bars of the piece contains two significant motivic patterns (separated by the barline, in Musical Score Example 1, Figure 24.1). The second pattern (in the second bar) can be interpreted as a re-ordering or inward re-shaping of the first; the two have many notes in common. The semitone is the most common interval and the tritone is also structurally significant.

Figure 24.1

Musical score example 1.

Throughout the piece, both of these patterns are further reduced, re-shaped and split into fragments, which are often inverted (this can be clearly seen in the later musical score examples; I have drawn boxes around some of the more signifi-cant recurrences, placements and transformations). However, the patterns are also recalled in their original form from time to time. The accented, syncopated rhythm of the first pattern gradually becomes a distinctive figure in its own right. The harmonic language is post-tonal but I have avoided extremely dissonant sonorities such as cluster chords. In bars 6–7 (Musical Score Example 2 in the following section), the first pattern is harmonised with major and minor thirds [0,3,4]; the second with a whole tone sonority [0,4,6]. While the music often ‘toughens’ the film, it was important to avoid heavy-handedness.

Meanwhile, the ensemble writing features an increasing amount of differentiation and tension between the expressive, soloistic piano part and the electronic lines, in an effort to make them more stylistically distinct from one another. This polarisation is intended as a musical commentary on the film’s formal contrasts, the conflict between ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ elements. The piano part’s hairpins, abrupt dynamic changes, trills and tremolo are juxtaposed against the more thoroughly mechanical qualities of the electronically sequenced lines. Trills and tremolo have an ‘uneven’ and unpredictable quality in the hands of a real pianist; when notated and played back on a score-writing programme like Sibelius they just sound like electronic pulsation, unless the composer intervenes. While this instrumental set-up contributes an additional layer of meaning to my musical reading of Lichtspiel Opus 3 and makes the separation between certain musical lines more audible, it can also be read as a more general comment on the forced marriage between live (music) and pre-recorded media (film) which commonly occurs in a silent film concert setting. Applying these ideas within the musical ensemble is a further extension of the concept. The theorist Marion Saxer observes:

In this piece, it might be said that the film ‘plays’ the live musicians via the electronic parts and the headphone click-track. The last few bars have quite an arresting effect, as the electronic parts take over, swamping the musical texture with increasingly rapid, impossible-to-play patterns as the live instrumentalists drop out.

Audiovisual analysis: case studies

![]()

I worked from a video of the restored film, taken from the commercial DVD release Berlin: Die Sinfonie der Grosstadt and Melodie der Welt (Berlin: Symphony of a Great City and Melody of the World), dir. Walter Ruttmann, 1927/1929 (Munich Film Museum 2008). The duration of the film is 3’20.0”. Two audio recordings of my piece are available to listen to on the companion website for this book. The first is a completely electronic (MIDI) recording (Video 24.1) , created using sampled instrumental sounds and the second is a 2017 live concert performance by the Riot Ensemble, featuring the two performers (Adam Swayne and Jude Carlton) playing along to pre-recorded audio, as intended (Video 24.2). The score is exactly the same for both versions. There are six musical score examples in the audiovisual analysis which follows, with corresponding video clips online. Sibelius timecode references and important visual movements and rhythms are indicated with arrows. I have also drawn boxes around some of the more structurally significant and rhythmically disruptive musical patterns, in order to make the analysis as clear as possible.

![]()

The music begins at 10.0”/bar 6, as the ‘III’ graphic reaches its full size, with an energetically syncopated chordal texture (the preliminary part of the title sequence is left silent). The film begins properly at 14.0”/bar 8, with a procession of tall, overlapping, oscillating blue rectangles positioned on the left of the screen, over a dark background. As they are re-oriented diagonally towards the centre of the shot, their movement becomes increasingly fast-paced and erratic. The music increases the intensity of this opening sequence with a disorientating, abruptly introduced ‘surge’ of polyphonic activity in bars 8–10. Pulsating rhythmic and melodic patterns are layered at different speeds and overlap one another. I have drawn boxes around some of these overlapping patterns in Musical Score Example 2 (10.0”/bar 6 to 20.0”/bar 11), which is shown in Figure 24.2 (Videos 24.3 and 24.4).

![]()

Figure 24.2

Musical score example 2.

In Musical Score Example 3 (22.5”/bar 12 to 32.5”/bar 17) (Figure 24.3), a snaking arrow traces a diagonal path across the screen, merges into a rectangle and fades to black. This ‘melodic phrase’ occurs four times (indicated by diagonal arrows in the score) (Videos 24.5 and 24.6). With each repetition there is an increase in ‘dynamic’ intensity and volume (indicated by the steeper gradient of each line), as the arrow travels further across the screen and the rectangle increases in size, finally breaking apart from the central shape and morphing into a trapezoid. This creates quite an expressive, dramatic effect even when the film is played silently. The music punctuates and embellishes these fluctuating visual intensities, increasing the already quite strong momentum and directionality of the sequence. It does so by repeating and elongating an ascending figure in the bass and using melodic variation, localised heterophony, spasmodic rhythmic ornamentation and ascending harmonies, with a new pitch centre in each bar. The flurry of musical activity ceases each time the screen fades to black with a ‘visual silence’; only the vibraphone continues with its soft, irregularly pulsating dyads. Meanwhile, the counter-melodies in the electronic harpsichord part, derived from the bassline in bar 8 (see Musical Score Example 2), are initially placed where they are for purely musical reasons and subject to inward re-shaping, although they gradually intrude on and overwhelm the surrounding parts, contributing additional intensity and disruptive power.

Figure 24.3 Musical score example 3.

In the visual sequence beginning at 33.5”/bar 18, a square appears to rapidly advance and ‘flash’, resulting in an incisive visual ‘pulse.’ This creates ‘ripples’ at a fairly regular tempo; the screen ‘vibrates’. In Musical Score Example 4 (Figure 24.4), the music exactly imitates the rhythm or ‘metre’ of this visual gesture in the bassline (Video 24.7). The pattern (indicated with the downward arrows in bars 18–20, electric piano lower stave) runs 3/8+3/8+3/8+4/8+3/8+3/8+4/8. Building on this irregular foundation, the music also creates a gesture analogous to the ‘ripples’ with a hocketing technique, as the vibraphone dyads are placed a semi-quaver behind the bass. Meanwhile, earlier figures are recalled and elaborated on melodically in the upper parts. In bars 19–20 the melodic elaboration in the harpsichord line (a familiar pattern derived from the opening bars) proceeds at its own pace again (quintuplets/crotchet 150); this superimposed rhythmic complexity is somewhat ‘indifferent’ to both the bassline and visual ‘pulse’ and has a purely decorative function. Overall, the music continues to suggest multiple rhythmic perspectives here, while simultaneously emphasising formal continuities.

![]()

Figure 24.4 Musical score example 4.

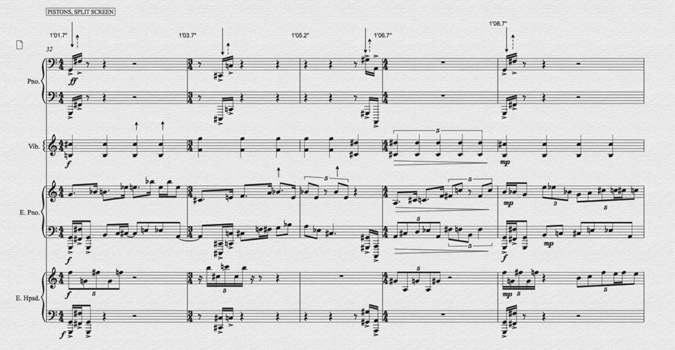

At 1’01.7”/bar 32 there is a split-screen effect and a pulsating, very machine-like sequence begins. Again, there is a close synchronicity between the two media, as a major seventh aggressively punctuates the downward motion of each ‘piston’ (indicated in Musical Score Example 5 [Figure 24.5] with the downward arrows) (Videos 24.7 and 24.8). This musical attack sharply intensifies the visual gesture; it seems less forceful when the film is played silently.5 In between each punctuation, free melodic elaboration continues in the surrounding parts, with individual notes sometimes ‘catching’ the smaller, upward-moving rectangles (indicated with the smaller arrows). After each punctuation, the pitch centre changes. First the music ‘modulates’ up a tritone from G to C sharp, then down a third to A. These three pitches form the pattern [0,4,6], which relates to the whole tone sonority in bars 6–7. This cyclical harmonic movement briefly superimposes a dynamic forward motion onto the visual sequence which it does not possess when played silently, making the visual repetitions seem more varied. Slightly later, the musical pulse begins to become submerged as quintuplets and septuplets smudge the texture, and free melodic elaboration starts to take over. The music becomes more independent, and briefly takes some ‘time out’ to rework material according to its own internal structural principles while the visual repetition continues.

![]()

Figure 24.5 Musical score example 5.

Musical Score Example 6 (beginning at 1’18.7”/bar 41) (Figure 24.6) sees the first proper appearance of curved lines/shapes in the film (Videos 24.9 and 24.10). In the music, there is an increase in rhythmic dissonance and layered complexity, from 5:4 in the first half of the bar, to 7:6:5:4 in the second. These superimpositions are brief further examples of temporal ambiguity, overlaid onto the visual patterns here in order to increase energy and dynamism. The tentative, fluctuating melodic pattern at crotchet 105 (septuplets) in the middle of the bar connects the two rhythmic textures in a somewhat unstable manner, during the visual ‘silence’. Then, at 1’23.7” the shot composition changes, as the screen is split diagonally from the lower left corner to the upper right. Curved figures ‘climb’ up the central dividing line. Their movement begins to accelerate and becomes more irregular and fluid at 1’28.7”/bar 44:3, then decelerates around 1’31.7”/bar 46. Also, from about 1’30.7”, the diagonal line begins to ‘wilt’, morphing into a curved form. This is one of the moments in the film when its rhythmic freeness and fluidity are most strikingly apparent; the energy and irregularity of the music help to accentuate it.

![]()

Figure 24.6

Musical score example 6.

However, since the change in shot composition at 1’23.7” is not especially dramatic or striking when viewed silently, the music (bar 42) marks the sectional break here much more decisively. The transition to the quintuplet dyads sounds like a tempo change (to crotchet 150) and the pitch centre drops down a major third, from C to A. There is a sudden decrease in the dynamic level and the texture becomes slightly more vertical, dominated by the quintuplet dyads. The role of the music here might be characterised as analogous to a change in stage lighting, or even a ‘jump cut’; an act of temporal partitioning which helps to articulate the film structure more clearly. While many of the instrumental lines subtly track the upward movement in the picture, the descending major thirds in the harpsichord part, which begin momentarily before the sectional break, add decorative contrary motion, a kind of reverse shadowing. As in previous sections, this contributes further to the multilayered effect and prevents the music from becoming sterile or predictable.

Finally, in Musical Score Example 7 (beginning at 2’11.7”/bar 58) (Figure 24.7), a curved figure emerges and begins to ‘dance’, with slow, jerky but evenly recurring rotations (indicated with the upward/downward arrows) (Video 24.11). This is the most ‘anthropomorphic’ gesture in the whole film so far, yet it can be traced back to the earlier movements of curved forms from 1’23.7”. The music undergoes a tempo change/metric modulation here (from crotchet 120 to 90) and there is also an implied metre change as the stuttering, lopsided, waltz-like figure emerges (notated as triplets). The surrounding parts gradually disrupt the more ‘vernacular’-sounding dance gestures. The pitch centres alternate between F, G and B. This forms the trichord [0,2,6], another whole tone grouping similar to [0,4,6], the trio of pitch centres familiar from the earlier ‘piston’ sequence (Musical Score Example 5). Like before, this cyclical harmonic movement makes the visual patterns seem more dynamic and less repetitive than they are when played silently. The recurring musical device also suggests a formal association with the earlier sequence. Therefore, this passage is an example of the music not only intensifying and enlivening visual gestures but also implying structural parallels and connections between contrasting sections, contributing additional cohesion to the film overall.

![]()

Figure 24.7

Musical score example 7.

The purpose of this audiovisual analysis has been to demonstrate how the compositional ideas outlined in the earlier sections of this chapter are made to work in practice. The piece continues in a similar vein; from 2’59.0” the tempo of both the film and music become much more frantic, as earlier visual and musical material is restated and rhythmically compressed. At 3’02.2” and from about 3’09.4” to the end, the geometric and curved elements in the film are decisively merged together for the first time. In the music, fast, dotted rhythms and frenetic electronic flourishes confront one another in a frenzied climax.

Conclusion: audiovisual ‘heterophony’

Reading Lichtspiel Opus 3 as a musical score reveals and elucidates the film’s unusual blend of influences from different media and historical periods. Rutt-mann’s abstract moving image aesthetic looks backwards and forwards at the same time, retrospectively embodying a tension between tradition and modernity. His rejection of montage technique in favour of a more evolutionary, evenly proportioned and organic time character distances Lichtspiel Opus 3 from the more famous examples of 1920s non-narrative cinema, such as Ballet Mécanique (Léger and Murphy 1924) and Le Retour a la Raison (Man Ray 1923), which are unmistakeably futuristic by comparison.6 However, as my analysis has shown, the visual elements in his work are frequently geometric and contrasting, with movements recurring at an uneven pace, running the whole gamut from fluid to spasmodic, metronomic to irregular. Modernist themes and ‘hard’ imagery are by no means neglected in Lichtspiel Opus 3.

A device such as counterpoint is a thoroughly institutionalised element within music; yet its deployment in an approximately analogous way within abstract moving images, as pulsating visual patterns which overlap, interrelate and reciprocate one another, remains a relatively ‘avant-garde’ concern. Perhaps this merely serves to reiterate the point made near the beginning of the second section of this chapter: there will always be subtle perceptual and behavioural differences between music and abstract film, even when their spatio-temporal characteristics spring from the same impulse. However, I would argue that my musical reading of the film images in Lichtspiel Opus 3 points away from these apparently irreconcilable differences, drawing the two media closer together without degrading them. By taking influence from Nancarrow’s formal techniques and also combining live performers with electronically sequenced parts, I have been able to creatively reinterpret Ruttmann’s complex visual rhythms and choreographic structures, articulating and elaborating on their modernist qualities without completely obscuring their connection to more traditional, developmental classical music structures and ‘romantic’ performance traditions.

Moreover, I have sought to create and demonstrate a working model of film music, which allows room for precisely synchronised musical gestures and relatively self-governing musical textures to co-exist. Superimposed, clearly discernible layers of contrasting rhythmic activity make it possible to create a polyphony of musical perspectives. This is not a ‘universal’ theory of film music; there are other, more narrative-based contexts in which formalist devices like these might obfuscate rather than reveal or enhance. Yet, in bringing the insights and methods of later musical thought to bear retrospectively on Lichtspiel Opus 3, my music has explored new modes of mediation between historical moving images and contemporary classical music. The internal relationships of both media interact and overlap, resulting in a set of dynamic interrelations across sight and sound.

Like many practitioners and theorists before me I have often been attracted to the term ‘audiovisual counterpoint.’ Obviously the music for Lichtspiel Opus 3 is very polyphonic when taken by itself. As frequently discussed, the film has sections which include overlapping, interrelated movements. However, the relationship between the film and the music cannot be described as ‘counterpoint’ as the two media are not, strictly speaking, completely independent of one another. Rather, they represent different versions of one another, played at the same time. Heterophony is defined as the ‘simultaneous performance of a melody and a variant of the same melody’ (Bowman 2002: 78). Therefore, ‘audiovisual heterophony’ would, perhaps be a more precise description of the multimedia texture captured in my score for Lichtspiel Opus 3. This relates back to Nicholas Cook’s theory of multimedia, cited earlier: similarity is the starting point for a ‘transfer of attributes’ between two media (especially music and film). However, it is only a starting point, no more. Meaning is created from a ‘limited intersection of attributes’, not ‘complete overlap or total divergence’ (Cook 1998: 81–82). My compositional approach is both precise and flexible, demonstrating that a close audiovisual relationship need not compromise the structural and aesthetic integrity (and autonomous potential) of the musical soundtrack.

Bibliography

- Adorno, T.; Eisler, H. (1947) Composing for the Films. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Andriessen, L.; Schönberger, E. (1989) The Apollonian Clockwork: On Stravinsky (trans. J. Hamburg). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bowman, D. (2002) Rhinegold Dictionary of Music in Sound. London: Rhinegold Publishing Ltd.

- Cook, N. (1998) Analysing Musical Multimedia. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cowell, H. (1930) New Musical Resources. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Eisenstein, S. (1975) The Film Sense (trans. J. Leyda). New York: Harcourt Brace.

- Elder, R.B. (2008) Harmony and Dissent: Film and Avant-Garde Art Movements in the Early Twentieth Century. Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

- Gann, K. (1995) The Music of Conlon Nancarrow. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Griffiths, P. (1995) Modern Music and after. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lawder, S.D. (1975) The Cubist Cinema. New York: New York University Press.

- Leeuw, T.D. (1977) Music of the Twentieth Century (trans. S. Taylor). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Le Grice, M. (1977) Abstract Film and Beyond. London: Cassell & Collier Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

- Marks, L.E. (1978) The Unity of the Senses: Interrelations among the Modalities. New York: Academic Press.

- O’Konor, L. (1971) Viking Eggeling: Artist and Film-Maker, Life and Work. Stockholm: Royal Swedish Academy of Letters, Histories & Antiquities.

- O’Pray, M. (2003) Avant-Garde Film. London: Wallflower Press.

- Rees, A.L. (2011) A History of Experimental Film and Video. London: BFI & Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rogers, H. (2013) Sounding the Gallery: Video and the Rise of Art-Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rosen, C. (1971) The Classical Style. London: Faber and Faber.

Chapters in books

- Ahlstrand, J.T. (2012) Berlin and the Swedish Avant-Garde. In: H. Berg (ed.) A Cultural History of the Avant-Garde in the Nordic Countries 1900–25. New York: Rodopi. pp. 201–229.

- Elsaesser, T. (1987) Dada/Cinema? In: R.E. Kuenzli (ed.) Dada and Surrealist Film. New York: Willis Locker & Owens. pp. 13–28.

- Hughes, E. (2008) New Technologies and Old Rites: Dissonance between Picture and Music in Readings of Joris Ivens’s Rain. In: R.J. Stilwell; P. Powrie (eds.) Composing for the Screen in Germany and the USSR: Cultural Politics and Propaganda. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. pp. 93–106.

- Moritz, W. (1997) Restoring the Aesthetics of Early Abstract Films. In: J. Pilling (ed.) A Reader in Animation Studies. Sydney: John Libbey.

- Rees, A.L. (2007) Frames and Windows: Visual Space in Abstract Cinema. In: A. Graf; D. Scheunemann (eds.) Avant-Garde Film. New York: Rodopi. pp. 55–77.

- Rees, A.L. (2009) Movements in Art, 1912–40. In: S. Comer (ed.) Film and Video Art. London: Tate Publishing. pp. 26–46.

- Richter, H. (1949) Avant-Garde Film in Germany. In: R. Manvell (ed.) Experiment in the Film. London: The Grey Walls Press. pp. 219–234.

- Richter, H. (1957) Dada and the Film. In: W. Verkauf (ed.) Dada: Monograph of a Movement. New York: George Wittenborn, Inc. p. 64.

- Saxer, M. (2014) Paradoxes of Autonomy: Bernd Thewes’s Compositions to the Rhythmus-Films of Hans Richter. In: C. Tieber; A.K. Windisch (eds.) The Sounds of Silent Films: New Perspectives on History, Theory and Practice. Palgrave Studies in Audio-Visual Culture. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 192–208.

- Velguth, P. (2006) Notes on the Musical Accompaniment to the Silent Films. In: S. MacDonald (ed.) Art in Cinema: Documents Toward a History of the Film Society. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. pp. 151–155.

Journal articles

- Bordwell, D. (1980) The Musical Analogy. Yale French Studies. (60). Cinema/Sound. pp. 141–156.

- Heller, B. (1998) The Reconstruction of Eisler’s Film Music: Opus III, Regen and the Circus. Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television. 18(4). pp. 541–559.

Online resources

- McDonnell, M. (2003) Notes for Lecture on Visual Music. Available online: www.soundingvisual.com/visualmusic/visualmusic2003_2004.pdf [Last Accessed 16/03/16].

- Murcott, D.; Kelly, J. (2012) The Music of Conlon Nancarrow: Impossible Brilliance – Festival Programme. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/51372358e4b09e6afa7c7ffa/t/5512e9eae4b039d26a9136f8/1427302912261/Impossible+Brilliance+Programme.pdf [Last Accessed 13/3/20].

Filmography

- Ballet Mécanique (1924) [FILM] dir. Fernand Léger; Dudley Murphy. Kino Video/Douris Corp.

- Le Retour a la Raison (1923) [FILM] dir. Man Ray. Kino Video/Douris Corp.

- Lichtspiel Opus 1 (1920) [FILM] dir. Walter Ruttmann. Munich Film Museum.

- Lichtspiel Opus 3 (1924) [FILM] dir. Walter Ruttmann. Munich Film Museum.

- Rhythmus 21 (1921/4) [FILM] dir. Hans Richter. Kino Video/Douris Corp.

- Symphonie Diagonale (1924) [FILM] dir. Viking Eggeling. Kino Video/Douris Corp.

DVDs

- Avant-Garde: Experimental Cinema of the 1920s and ’30s, Films from the Raymond Rohauer Collection, dir. Various (Kino Video, Licensed by the Douris Corp, K402 DVD, 2005).

- Berlin: Die Sinfonie der Grosstadt and Melodie der Welt (Berlin: Symphony of a Great City and Melody of the World), dir. Walter Ruttmann, 1927/1929 (Munich Film Museum, 2008).