Stories in user experience design are not “made up”—they are based on real user data and then distilled to effectively illuminate the design process. It all starts with collecting stories during user research. Whether you are building a picture of audience demographics, doing an in-depth task analysis, or seeking a broader understanding of user motivations and desires, you, too, can collect valuable stories.

The stories you hear from users give you a first-person view of the world from many unique perspectives. They help you understand the goals, motivations, and preferences of the people you design for. They help you understand their personalities and their quirks, which you can use to create a rich, textured experience.

The most obvious place to collect stories is in qualitative research: ethnography, contextual inquiry, focus groups, and interviews all center on observing (and listening to) people. As we listen, we hear not just what they choose to say, but also how they say it and what they leave out. Some stories are explicit, offered as a straightforward explanation and ready to be collected. Others must be teased out, deduced from what is not said, or discovered by also collecting details about the context.

When you are there, you can hear and see all of the small details that make up an experience. This is especially true of emotional reactions, or those happy accidents that only occur when you don’t plan them.

If you can’t be there, you can find stories all around you. For example, user research that primarily aims at learning answers to a specific set of closed questions can also be a source of stories. Surveys and usability testing usually include opportunities for people to answer open-ended questions or to comment. These comments may be very short stories, or might hint at a story that can be collected later.

Even if you can’t do direct user research, you can glean stories from many indirect sources.

Search logs and server logs. Web server logs, path analysis, search logs, and other ways of measuring user behavior give you a quantitative look at what people are doing as they interact with your site or product. This data is one side of a conversation between users and the site. By seeking the story behind the data, you can get a better view into how and why people use your products. The story in Chapter 7 on Golden Pages is a good example of how data from server and search logs can lead to a more detailed story.

Customer service records. If you have access to records from customer service or support queries, you will find many stories hidden there. Emails or Web contact forms will have questions in users’ own words, often with a rich description of the context. Customer support logs provide an overview of the types of questions being asked. You can treat these entries as a form of observation.

Training and sales demos. People who teach training classes or do sales demonstrations have direct contact with users as they learn a new product. This information is rarely collected, so you can tap into a new source of information by taking the training department to lunch. They often will have a great collection of anecdotes about questions they are asked in their classes, stories they have heard about how the product is used, or the way users explain a problem. All of these can be the beginning of a story.

Market research. General industry research with a specific audience or market segment often contains raw material for stories like images, emotional responses, or even small snippets of interviews.

Attitudinal data. Satisfaction surveys of customer opinions and attitudes are useful sources of stories, especially if they include open-ended questions or if they ask for examples.

You can use material from these sources along with stories gleaned from the user research you are currently doing. Each source will provide you with slightly different types of stories, all useful in creating a rich and well-rounded view of the user experience.

Another source of stories are the many social media networks. Official and informal support sites and user forums can be an easy way to find stories about using specific types of products or solving problems. More general social networks can provide insights into many different kinds of activities and interactions.

It can take work to dig through these sites, but they can be rich repositories of information. Not only do people tell stories, but others in the group react to them and often expand on a first comment or question with stories of their own. This gives you ready-made clusters of stories on a related topic.

You don’t usually set out to capture stories directly. But with a little effort, you can watch for story opportunities and structure your user research to allow time to listen to them.

When you plan a user research session, you usually have a series of questions in mind, and you set up the session so you can get those answers. You probably include time for follow-up questions or to probe more deeply into motivations and attitudes. Listening for stories is no different. When you allow time for a bit of wandering, or give the people you work with space to think carefully, you can get beyond the top layer of information to explore not only the background but also the deeper layers of experience behind their answers. That’s where you will often find the best stories.

For example, you might be testing a new concept for a television remote control. You ask each person you work with to complete a series of tasks to see how easily they can use the new design and how well the features fit into the way they might use the remote. After each task, you might ask them to assess their experience. That conversation might go something like this:

Researcher: How was that? Was that easy for you? Did you have any problems?

Participant: Oh, no, no, no. I had no problems. It was very easy. My husband would never be able do this. But I had no problems with it.

As the researcher, you now have two choices. After you write “no problems” or “successful in task” on your notes, you can continue to the next task. Or you can back up to that throwaway comment about the participant’s husband. There is a story there, and you have a chance to find out what it is. What is the difference between these two people? How do they use technology in their household to work around (or make use of) this difference? This sort of story is not just a source of material to spice up a final report. These stories encourage new understanding and point to previously unnoticed usage areas. In other words, these stories can lead to new product ideas!

The simplest way to elicit stories is to ask for them. Give the people you are working with permission to give you more than the shortest possible answer. Instead of asking several short questions, you can just ask one open-ended question. Or you can follow up with a broad invitation to talk. It might go something like this:

You: How often do you buy things online?

User: At least once a week. Sometimes more. Or do you mean for work? I do that all the time.

You: Let’s stick with things you buy for home, for right now. What was the last thing you bought online for yourself?

User: Oh, it was a sweater I saw in a catalog.

You: Tell me about that.

User: I still get all this junk mail, but some are from stores I like. I flip through them and mark things I might want. Most of the time that’s all I do, but sometimes I’ll go to the Web to see if it’s still on sale. Waiting...that’s a good way to keep from spending too much money. All the good things are gone, so it takes the decision away. But if I really like something ...

Now you know that this person not only buys things online, but also still browses catalogs to find things to purchase. You also know that they play a little game with themselves to make sure they only buy things they really want. This is a detail that you can weave into a larger story about how people mix different sources of information as they shop.

Once you get into the habit of asking “Why?” or “Tell me about that,” you will find that just asking people to tell you about themselves is often enough to get them started. Remember: Stories start with listening. Your job as an interviewer is to give the participants your attention and make it comfortable for them to talk.

Another way to collect stories is to get a group of people to tell stories to each other. There’s a natural tendency for one story to lead to another and for each person to want to tell their own story. You can make use of this bad listening habit to create more story-collecting opportunities.

One of the classic problems in focus groups is that the more confident participants can overwhelm those who are less confident about speaking up. This often includes people from lower social backgrounds or those who are not as well educated. According to Jon Cohen, who helped develop the BBC’s Read and Write literacy strategy in 2005, storytelling is a powerful means to allow people with low literacy to express themselves.

“It lays the foundation for personal stories which bring to life how respondents feel about any commercial and social issue, brand, or product in their lives.”

—Matthew Secker, Research Magazine

For example, you can weave storytelling into a focus group session. In a typical focus group, you might start with a prototype of some kind, perhaps just an image or a story that the moderator tells. Then the moderator asks a series of questions. Some people will leap forward to answer the questions. Some of them will tell a quick story as an example. As the moderator, you can use this moment to encourage others to tell their own stories, with each one building on the last. As with any group, you have to make sure that everyone gets their turn. These quiet participants may be more comfortable telling a story, or adding a little bit to another story, than expressing an opinion or answering a direct question.

One of the side benefits of small groups like this is that it gives people a chance to be listened to and to have their experiences acknowledged by others. When you can create a safe place for this to happen, you will gain much deeper insights into the user experience.

The technique of collecting narratives is at the heart of the Critical Incident Technique developed by John Flanagan. Instead of asking for an opinion about a product or experience, you ask the person to tell you about a specific recent experience. This formal methodology is often used for evaluating the performance of mission-critical systems, but you can use the general approach to get people to tell you the story of a single event. It can be an interesting way to get people to tell you about routine experiences.

These stories not only give you examples of events or user behavior, but also information about the context in which those events occurred. You’ll use these contextual details later when you construct your own stories.

If you are watching as someone does something, watch how they do it in addition to listening to what they say about it. Their behavior may offer a story as rich as their words.

Sometimes the simplest activities may offer unexpected insights into the user experience.

While we were collecting stories for this book, we heard a lot of anecdotes about seemingly small observations that led to large improvements to the user experience:

One group watched people unpacking a large, heavy piece of equipment and had the insight that they could design the box as a lift-off lid: instead of lifting the equipment out of the box, the packaging could slide off the top.

A documentation manager didn’t discover until visiting customer sites that many of the users had never even unpacked the product manuals.

At a call center that covered three states, the best customer representatives kept a window open for each state, giving each of them a different background color.

You probably have your own stories like that. Details so small that no one would think to mention them that became the basis for an innovation.

When you go into a new situation, everything is unfamiliar and strange to you. Those early moments, before you become an “insider,” are your opportunity to observe stories about how people interact with objects in their environment and with other people. In their chapter on conducting site visits in User and Task Analysis for Interface Design, Ginny Redish and JoAnne Hackos talked about the importance of taking specific notes on the environment, including the way the furniture is arranged, the decorations and notes around someone’s workspace, the lighting, or any special clothing or safety equipment. Similarly, if you are in someone’s home or personal environment, you want to take notes on how they have arranged that environment to make it their own.

Anthropologists talk about contextual observation as a way of making the familiar strange or the strange familiar. Genevieve Bell and her colleagues at Intel study the home and familiar settings like kitchens. They talk about defamiliarization as a way of looking critically at a context or object to see it in a new way. In an article, “Making by Making Strange: Defamiliarization and the Design of Domestic Technologies,” they describe how they use detailed descriptions to force themselves to observe well-known settings closely and see a familiar environment and its objects in a new light.

Seeing the familiar in a new way can be difficult if you work in a specialist field like technology or medicine. You may have absorbed basic concepts to the point that you can’t imagine not knowing them. Stories from people encountering a situation that incorporates these concepts for the first time can help you and your colleagues remember what that experience is like.

Careful observation of the physical environment is also important if you are working in a situation that is new to you. We don’t usually tell stories about routine things. As Steve Denning puts it, “fish don’t tell stories about water.” So it’s up to you to notice these details and how they affect the people in the environment.

When you question basic assumptions, you’ll find new opportunities.

You may want to bring back pictures as a way of reminding yourself of what you saw and to give you images to illustrate your stories. Your notes and photos can also shed new light on what you heard. Do the users’ descriptions match what you observed? If not, you may have the beginning of an interesting story about different perceptions.

If you are used to conducting very structured research sessions, you may find that gently directing the conversation and flow of information is harder than just asking a series of prepared questions. Even when you are experienced at collecting stories, you need to be ready to deal with things that can derail your work.

Sometimes what people have to tell you is important to them but not that valuable to your research. Other times, it’s the opening to a much richer understanding. As a researcher, you have to be in control and practice the art of listening without being distracted from your goal. You don’t want to cut off someone who has a story they need to tell. (Remember, stories start with listening.) But you don’t want to let a story take you off track, either. Most of the time, you need to keep the user research session on track while remaining open to valuable tangents.

If someone veers off into a story that isn’t exactly what you are interested in, you need to decide how long to let them talk and find ways to redirect the conversation into the areas you want to hear about. You can do this by asking them to tell you more about an aspect of the experience they are describing that might be more relevant to your research. Or you can let them finish and then move on to your next topic.

You: How often do you buy things online?

User: All the time. The last thing I bought was a sweater. I used to knit my own sweaters. Actually, I was really into wool and did a lot of experimenting with dyes. Did you know that you can make dyes from natural products? They are a lot better for you than the chemicals that most commercial sweaters are colored with. I even collect things from the woods. Like there are certain barks that you can boil to make really nice brown colors.

You: That’s really interesting. Thanks for telling me about that. To come back to shopping, are you able to find knitted products that you like online?

If the person seems determined to avoid the topics you are interested in, that in itself might be an important piece of information, and you might want to take some time to find out why.

As you learn to handle these situations, keep focused on your research goals. Most of the time, you don’t want to go down a rabbit hole following a tangential story unless you are sure that there’s something interesting to be learned.

If you want to collect stories, you have to create a structure for your research sessions that allows the time for that to happen. One way to do this is to mix closed and open questions. You can start with simple questions that establish the topic and then ask a question that invites the person to give you more detail. For example, look at Table 6-1.

Table 6-1. ![]() http://www.flickr.com/photos/rosenfeldmedia/4459992066/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/rosenfeldmedia/4459992066/

A STRUCTURE FOR AN INTERVIEW | |

|---|---|

Do this... | Like this... |

Start with a question that establishes the activity you want to talk about. This question can be simply answered with a yes or no. | “Have you ever [done something]?” |

Then ask questions that build up a picture of how this activity fits into their work or life. You can even suggest answers from a standard list for these questions. | “How often do you [do that thing]?” “What makes you decide to [do that thing]?” “Would you say this is something you mostly do at work or at home?” |

Now, ask a question to get them to think about a specific example. | “When was the last time you [did that thing]?” |

Once they have a specific event in mind, you can repeat the situation, to be sure you have it right, and then ask for the whole story. | “Tell me about that.” |

Sometimes, there is not much more to say about the event, but if there is, you have accomplished two goals: found answers for your basic questions and given the person a chance to give you a rich example of the context and situation.

Something else to remember is that people respond to their environment. If you are sitting in a conference room with a camera looking over your shoulder, taking notes on a clipboard with a list of questions on it, don’t be surprised if people respond by trying to answer each question as succinctly as possible.

If you want them to open up, they need things to react to. These can be your own products or prototypes, but they might also be all the things in their office or even a “stage set” of a home. Proctor & Gamble, for example, built a Future Home Lab, which was a house complete with a laundry room, kitchen, and living room (along with a focus group room), where they could talk to customers within a context similar to the one in which their products would be used. They felt that they could get more accurate information from research when people were reminded of “real life.” Something about being in a kitchen, for example, reminds people that it can be messy and wet and hot. Or having their kids with them reminds people of how busy and sometimes chaotic their lives can be.

You need to make people feel comfortable talking. If they haven’t been listened to very much, they may need cues that it’s OK to tell their story in their own way. Or they may not be sure just what kind of information you are after, so you should be ready to ask more questions to gently keep them talking.

In casual conversation, people usually try to reach a state of equilibrium in which everyone contributes equally. As an interviewer, you want the person you are working with to talk more, so you have to create an unequal conversation pattern. There are some simple techniques to help keep the conversation flowing with minimal intervention from you. Judy Ramey’s “Methods for successful ‘thinking-out-loud’ procedures” describes techniques that are helpful. All of them allow you to take your turn in the conversation without interrupting the story.

Echoing. Repeat their last words or phrases back to them as a question. Echoing sets up a social dialogue and reinforces social conversation expectations: They say something, you repeat it; they say the next thing, because that is what is expected in conversation. Sometimes, even a nonverbal signal can be enough. What’s important is that you “take your turn” in the conversation and then give control back to them without distracting them from their train of thought.

User: This is confusing.

You: ...confusing...

User: Yes, confusing. I wasn’t sure whether I should use this link or that one.

Conversational disequilibrium. Let your statements trail off and end in an upward pitch, as if you were asking a question. The other person will usually complete your statement. This is another way to “take your turn” in the conversation and toss it right back to them.

User: I wanted to download that application, but the instructions were so confusing...(trails off and stops talking).

Here are five good ways for you to get them going again:

You (1): The instructions were confusing?

You (2): And you expected....

You (3): Confusing? ...Because....

You (4): So then you....

You (5): Mmmm hmmm.

In using any of these techniques, be careful not to put words in their mouth or offer interpretations. If you use their words, instead of trying to come up with a new way of saying the same thing, you are usually on safe ground.

When you build time for story collecting into your user research, you uncover completely new ideas. A rigidly structured interview only gives you the answers to the questions you ask.

Giving people space to tell their own stories lets you learn about things you would never have thought to ask about.

Often, people insist on giving the shortest possible answers. When you absolutely need to pull something out of someone who is either shy or otherwise uncommunicative, you can tell stories to get stories. When people hear a story, they are often compelled to respond with their own. So have a collection of small personal stories in your back pocket that you can pull out and tell if a participant is not giving you enough. For example:

You: Have you ever used an ecommerce Web site?

Participant: Yes.

You: How recently?

Participant: Last week.

You: What did you do when you were there?

Participant: I bought something.

You: Tell me about it.

Participant: I bought a sweater.

You: (wait)

Participant: (silence)

You: I got a sweater recently, too. It was for my husband... a blue one. For his birthday. Who did you buy yours for? Was it a special occasion?

Participant: Myself. I’d been wanting something bright and cheery, and I saw this red sweater...

The goal is to open up the discussion by sharing a small piece of personal information, putting you and the participant on a more equal conversational footing. The trick is to do this without asking a leading question. It doesn’t have to be more than a few words, but it does have to be true. Don’t pretend to like something you don’t or claim an experience you haven’t had.

Once you get them telling stories, you can use all the techniques above to keep them going. If they go back to short, crisp unhelpful answers, pull out another story. Remember, both your probing questions and short crisp stories establish and feed your relationship with the users. You like telling stories to people you have a relationship with, even if that relationship is paper-thin and transient.

In Chapter 2, we described the relationship between the storyteller, the audience, and the story as the Story Triangle. That bottom connection of the triangle between the storyteller and audience, or in this case between the user and you, is very important. So make sure they have a warm body to tell their stories to and not a cold paper survey with arms and legs.

You won’t have any stories (or even story fragments, images, or great quotes) if you didn’t take good notes. There’s nothing more frustrating than to half-remember a story, but not be able to find it in all your observation notes. If you don’t capture this information in a retrievable way, you will never go back and get it later. The way you write your notes can help.

There must be an ideal world in which there is enough time for everything we want to do, but the realities of most project schedules make it hard to fit in anything “extra.” And the rich detail that you need for stories is often “extra.”

The most important place to start is by turning on your “juicy story” filter so you are ready to take notes on any exceptional stories that come along. These field notes don’t have to be elaborate—just enough to remind you of the story so you can go back and write down all the details later.

Anytime you take notes, you are making selections about what is worth writing down. It might seem possible to record a description without any interpretation at all, but even the decision about where to place a video camera eliminates some parts of the story and emphasizes others.

When you are taking notes, it’s very helpful to write down the real words. The specifics of terminology or expression can be key to a story. With the specific words, patterns or other realizations may emerge during later review of your notes that you would never see if you didn’t have those words. Look at these four notes about someone deleting something by accident.

User deletes sentence.

User deletes sentence, comments that it was a mistake, retypes.

User deletes sentence. (Makes a face.) “Oh, I deleted what was already there.” Retypes sentence.

User deletes sentence. “Damn it. Why doesn’t it know that I wanted to add this information, not get rid of what I typed before!” (Bangs on the keyboard as he retypes the sentence.)

The first situation describes the event, but includes no emotional or behavioral detail. The second adds a richer description of the entire event. The third and fourth provide a direct quote and an indication of the user’s level of emotion, showing a different level of intensity in the reaction to the situation.

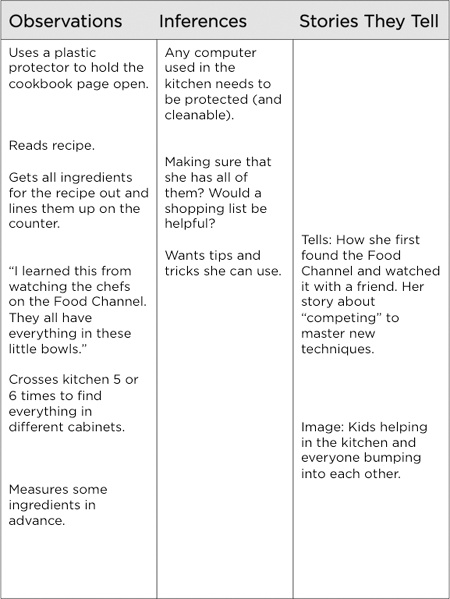

Since you are probably not just listening for stories, but collecting a lot of other information at the same time, you need to organize your notes so that there is time and a place for notes that might lead to stories. Ginny Redish, the author of one of the first books on usability, suggests using a multi-column format, as shown in Figure 6-1. The first column is for your observations, and the second for inferences you draw from those observations. In the final column, you can easily record both quotes and notes on potentially good stories.

Figure 6-1. Organizing your notes in columns (or marking them as you write them) makes it easier to find those insights that occur to you as you listen and observe, as well as the stories that might otherwise get lost.

Of course, you may be taking your notes in an electronic recording tool like Techsmith’s Morae or simply typing in a document or spreadsheet. If so, make two different markers for stories. You might use “Q” for a great verbatim quote and “S” for a possible story or word image. That way, it’s easy to find your story material among all the other notes and data that gets recorded, so that you can go back and listen to that part of the recording later.

You may not have time to write as much as the last example when you are taking notes “live,” but you will want to develop a note-taking style that lets you capture as much of the richness of the experience as possible. One place to start is by capturing as much of the real words as you can. Capturing exact words can also be a fast way to provide cues about details, like the level of domain knowledge, for example:

“I just closed the window.”

“I clicked on the little x thing.”

All of these techniques also work if you are taking notes by reviewing audio or video recordings. Whether you are watching the tapes for the first time or just going back over sessions or events where you were present, you still need to listen for the users’ own words and the way they tell their stories.

In this example, both users manage to close the window, but one uses technical language to describe her actions, while the other does not, suggesting very different relationships to the computer.

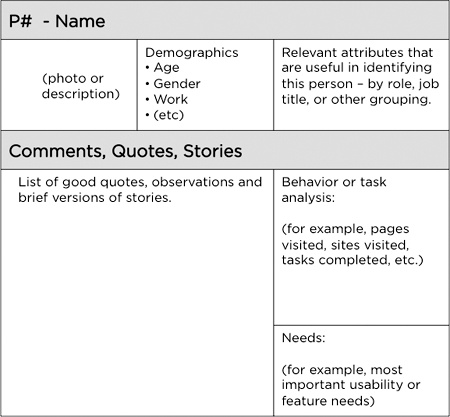

Another trick that helps make analysis easier is to write a summary of each person, pulling together all of your notes. A summary sheet might include the following information:

Demographic details and a description of the person

A log of their actions (where they went, what they did)

Quotes or observation notes that describe their attitudes

A brief note on any stories you heard

Any other specific details you are collecting, such as task success, preference, or other questionnaire data

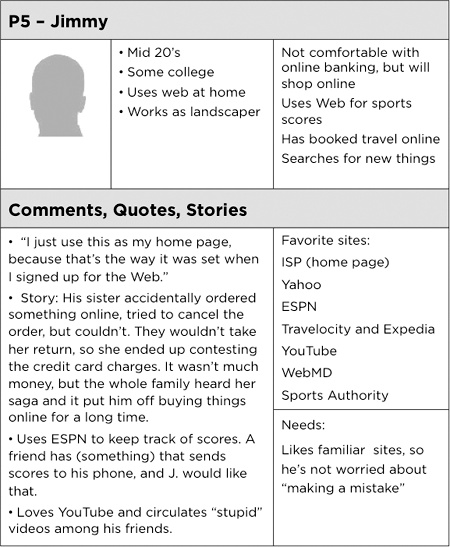

Put this into a structured format, and it will be easy to flip through your notes to find the stories. Figure 6-2 shows the basic template, and Figure 6-3 shows an example of a structured notes form.

This may seem like a lot of work, and you may not have time to do this for every participant on every research project. But when you can do this, it makes the analysis go much faster. It does something else, too. It gives you a chance to summarize the session while it is still fresh in your mind. You can get down on paper all the impressions that you took away from the session. In her writing on field studies, Judy Ramey calls this “collecting your head notes.” If you are working on a research team, it’s a good chance to pull everyone’s observations into one place. And it’s fodder for personas.

“Making by making strange: Defamiliarization and the design of domestic technologies,” G. Bell, M. Blythe, and P. Sengers, in ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI) 2005, Volume 12, Issue 2

“Methods for successful ‘Thinking-Out-Loud’ procedures,” Judy Ramey, in the STC Usability Toolkit: www.stcsig.org/usability/resources/toolkit/toolkit.html

Stories are all around us, if you just listen for them. The trick to getting good stories in your user research is to make the time for them.

Look for juicy stories in any user research, as you observe or review your notes.

Learn to ask questions that encourage people to tell you stories.

Thinking out loud procedures can keep the conversation and stories flowing comfortably.

You can find stories in many places, including search logs, customer service records, survey data, and even internal staff who work with users.

Take notes in a way that lets you find possible stories easily.