Throughout the book, we have talked about storytelling, but stories can be told in many different ways:

Oral stories: Stories told aloud with both storyteller and audience present.

Written stories: Stories communicated in written form. Usually, this means that the storyteller is not present and the story has to stand on its own.

Visual stories: Stories told (mostly) in pictures.

Multimedia, animation, or video: Stories told using spoken words, pictures, and moving images.

There are two formats that are especially important in the world of user experience design. Both formats mix a written or visual presentation with oral presentation, blending the mediums.

Reports: An obvious place for user experience design stories is in user research and usability reports or as a way to introduce a design concept, whether the report is written or presented orally.

Presentations: A particularly common business format, presentations are the performance storytelling medium for user experience design.

When we think about stories, we often imagine them being told aloud in real time. The audience may be one person, a small group, or many people. The occasion may be formal or informal. But whenever or wherever they are told, spoken stories are part of the oral tradition, because they are passed down from one generation to another as a way of transmitting and perpetuating culture. They can be as natural as any conversation, or they can be a well-rehearsed performance.

In user experience design, spoken stories can be an important part of analysis or design brainstorming. Retelling events from user research can remind you of their importance, help emphasize the most relevant details, or help you share those insights with a group. Stories can be part of working through a design or explaining it. Spoken stories are also part of that all-important business skill, the great presentation.

One important difference between telling a story and other story mediums is that you tell the story, so how you shape the story is affected by who you are, your relationship to the audience, and your skill (and comfort) with live performance. You are part of how the audience experiences the story. This is true of any story, of course, but it’s especially true in the case of a spoken story.

If you are feeling a little tentative about using stories in a professional situation, it might be because you’d rather not put the emphasis on yourself as the storyteller, because you are more comfortable observing than taking center stage.

There are advantages of delivering the story yourself, however. For one thing, you can see your audience as they hear the story. This means that you can adjust the story—adding details to answer questions and making it shorter if you have misjudged the length while you are telling it. You can use their faces and body language as cues, allowing you to fill in any confusing parts, or move more quickly if their attention is failing. As Doug Lipman, a consummate story performer, coach, and author puts it, oral stories are “dynamic, interactive, and sensory,” which makes them very different from simply reading a speech.

In a business setting, oral stories will only rarely be a stand-alone performance. They are most often integrated into a discussion or a presentation. For example, you might tell a story to illustrate a point and then make a smooth transition into a discussion of the implications of the story or a brainstorming session based on ideas that the story brings up.

Sometimes, you can create a story with the audience by suggesting the context or structure and then letting your listeners fill in the gaps, actively telling their part of the story.

Whatever the situation in which you decide to tell an oral story, you have a few extra ingredients to work with. Oral storytelling does not involve dramatic acting, nor is it simply a matter of getting the words out or reading a prepared speech.

There’s an old joke about how to get to Carnegie Hall. The answer is “practice.” Malcolm Gladwell makes the same point in his book Outliers: Expertise is partly a matter of time spent perfecting a skill. Gladwell estimates that 10,000 hours of practice separate people who are unusually good—i.e., outliers—from those who are just talented. Every time you craft a story or tell a story, you are banking hours of experience.

It is important to practice before you tell a story for the first time or if you are telling an oral story to an audience you can’t see—if you are giving a webinar, for instance, or telling a story for the first time on the phone to an audience you don’t know well. In those cases, you definitely want to rehearse. To prepare to tell a story, live with it for a while.

Barry McWilliams offers good advice on learning to tell a story: “Once you settle on a story, you will want to spend plenty of time with it. It will be a considerable period of time and a number of tellings before a new story becomes your own.” His article “Effective Storytelling: A Manual for Beginners” (www.eldrbarry.net/roos/eest.htm) goes on to offer some basic advice for a new storyteller. We’ve adapted it slightly here.

Read the story several times. Start by reading it as though you were meeting it for the first time; then proceed with concentration as you learn it.

Analyze its appeal. Think about the word pictures you want your listeners to see and the mood you want to create.

Research its background and cultural meanings. Prepare for questions from the audience and for flexibility in front of the audience, because you may need to adjust or explain the background of a story for various audiences.

Live with your story. The characters and setting become as real to you as people and places you know. If there are important facts, be sure you can include them easily and naturally.

Visualize it! Imagine sounds, tastes, scents, and colors. If you can picture the story in your head as you are telling it, it will be more real for you... and for the audience as well. Only when you see the story vividly yourself can you make your audience see it!

There’s a saying in storytelling, which is that every story is a personal story. Of course, if you tell a story about something that happened to you, it’s a personal story. But also if you tell Little Red Riding Hood—it’s a personal story. And if you tell a story about a research observation—it’s a personal story. What this means is that when you tell a story, there is always some part of you in it. That personal stamp might be what you choose to emphasize, or the style in which you tell it. It’s important to think about the authenticity of the story and your relationship to it, or what makes you interested in the story.

Unlike all the other story mediums, oral storytelling lets you shape your tale in real time, using your performance style, the pacing of the story, and the manner in which you connect and interact with the audience.

Any performance style requires making choices about what you want to sound like and what impression you want to make. To a tell story effectively, make those choices consciously.

Your performance style should be comfortable for you—not too different from your normal way of speaking, especially as you start out. Even professional storytellers who perform on stage must be able to incorporate their normal speaking voice in their work, as well as use their voice to serve the dramatic elements of their story. In fact, a performance voice, one that’s notably different from your speaking voice, sounds insincere. Or it will once your audience talks to you after the performance. The most basic guideline is to be open, honest, clear, and sincere. If you’re presenting in a conference room, you don’t want to sound like you’re performing in an Andrew Lloyd Webber musical. Imagine having a normal conversation with an opera singer who, when asked the time, starts belting it out in full operatic voice. Lovely—but jarring.

Another way to think about performance style is that as the storyteller, you are there to serve the story and help the audience understand it. You are there for the story. Anything about your performance that does not serve the story is superfluous. For example, you might be afraid that the audience is getting bored and start to speak faster, even when speaking faster does not serve the story. This choice, however well meaning, harms the story. Instead, you might consider changing the pace of the story or using your voice to emphasize points. If you are comfortable with the story, you can make connections between elements of the story.

As another example, some storytellers when faced with a particularly formidable audience might start speaking in a more authoritative tone with the notion that they will hold this tone throughout the story, even though it is clear that this tone is not their natural speaking voice.

As Doug Lipman described earlier, the oral storyteller has many tools to choose from and multiple channels through which to deliver their story. Relax and allow your performance style to be simple and only one of the many contributing tools you use for delivering your story.

After your performance style, the next element to add is pacing. Speak at a comfortable pace for both you and your audience. Don’t rush through your material or be too slow. Your pace does not need to be uniform. Use pacing to draw the audience in to the particular points you want to make or to shift from a detailed level to the big picture and back. There are two forms of pacing in storytelling—presentation pacing and narrative pacing.

Presentation pacing is how fast or slowly you talk, and to some extent how succinct or sharp your speech is. Think of presentation pacing as a way to influence the emotional response of the audience. For quicker, exciting, energized parts of the story, you can speed up. For slower or sadder parts of the story, you can slow down. Of course, this is only a general guideline and not a rule. You can also work with the transitions from one speed to another, using them to signal movement from one structural element in the story to the next.

Narrative pacing is about how fast or slow the story goes. This is not “words-per-minute,” but how much time is compressed or expanded in the details and structure of the story. For example, a story might focus on examining one small moment or jump through time from one event to another taking place much later.

We like to stick to positive advice, but there are a few things you should avoid, especially as you are starting out.

Don’t try to do voices and accents. Unless you are very sure of yourself, a very good performer, and have a safe audience who can give you feedback on it first, you can easily turn your characters into caricatures or sound like you are making fun of the people the story is about.

When in doubt, keep it short. There are no rules for how long (or short) a good user experience story can be, but no one was ever penalized for being too brief. When you are telling a story in person, you can always elaborate if you are asked to.

Don’t be afraid of silence. Don’t fill every second with the words of your story. You can choke your story with too many words or when words flow without a break. Use silence to allow the story to breathe, emphasize important points, or provide an opportunity for the audience to build your images in their heads.

We’ve been talking about the importance of reacting to your audience and watching their reactions. With more global UX projects, much of your meeting time is spent on the phone. New media like webinars are another situation in which you may be telling a story to an audience you can’t see. Here are a few tips for those situations:

Give the people on the phone enough time to react. Don’t let the performance pacing drag, but add a few seconds between sections of the story to make sure they have time to catch up.

You might want to have at least one person in the room with you, so you have someone to make eye contact with.

Make sure that your story doesn’t rely on gestures, props, or facial expressions. If you are using a screen-sharing tool, you can show photographs, documents, or software, but pointing with the mouse just isn’t the same as using your hand or being able to put something right in front of the audience.

Explain with examples whenever possible to create a vivid description. Use metaphors and similes for their expressive possibilities. Both use comparisons of two unlike things. Metaphors use an image or a description in an unusual context: lightening response time or bulletproof code. Similes use the words like or as: slow as a turtle or solid as a rock. People on a conference call are listening to a lot of words, often spoken by people who sound alike and whose faces can’t be seen. They are suffering from visual deprivation. Using verbal imagery helps them see what you are talking about instead of just hearing more words.

Using stories in a business setting requires striking a balance. Stories add interest and depth to a report or presentation, but too many stories can make your work seem trivial to people who may be more used to facts and figures. This can be especially true if your stories aim primarily for an emotional response, rather than being closely tied to data.

You can tell a story to introduce a topic, illustrate a point in the middle, or sum up a series of factual points. Your goal is to find the sweet spot where a good story can help you engage the audience—that’s the moment when they are ready to hear a story.

For many people in user experience design, written communication is a primary form of communication. If you work on a geographically dispersed team, you may rely on written communications to span time zones. If you are a consultant working with your clients from the outside, the written reports you leave behind may be as important as your in-person interactions.

Written stories can be a part of any design communication, such as personas, user research, usability reports, or design documentation.

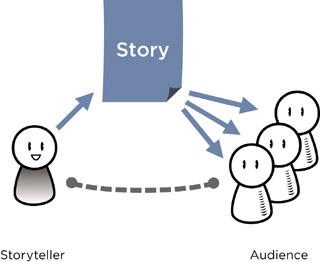

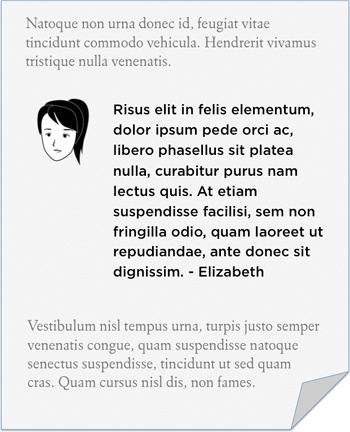

The biggest challenge for including stories in written communications is that you are not there to tell the story. Many of the techniques of oral storytelling are simply not available, because the readers control the pacing and hear the words only as they imagine them. Perhaps more important, you do not know who will read your story and thus will not be able to adjust the story to fit. As you can see in Figure 15-1, this does not mean that the Story Triangle doesn’t exist. But you won’t get direct feedback from the audience and will only learn about the impact of the story outside of the immediate storytelling context.

Figure 15-1. In a written story, communication between the storyteller and the audience is only indirect.

When you create a written story, you have the advantage of being able to edit it into a single form and maybe even control the presentation. You also have an audience that can read the story at their own pace and go back over sections if they need to.

As you plan your written story, here are a few thoughts to keep in mind:

Keep the story as long as it needs to be, but no longer. There is no rule for this, but in general, more people will read a shorter story than a longer one.

Keep the story crisp. Set the context efficiently, choosing details that will help the audience understand the story.

Don’t let it get weighed down with unnecessary description or side comments. You might get away with this in oral storytelling, but it’s hard to put asides into a written story.

Use all the tools of information design to shape the way the story looks. White space, illustrations, and other visual elements give the story its own place on the page, and can suggest the pace of the narrative.

Decide on the voice for the story. Will it be in third person, with a narrator describing the events from the outside? Or in first person, taking on the voice of the central character?

If you are using a story to share a detail about a user, just tell the story. Don’t make it a story about a story.

Think about how you frame the story in a larger document. It might be part of the main text or set off in a box or some other device.

Make the point of the story explicit. You are not present to lead a discussion or adjust the story so the audience “gets” it, so either build your conclusion into the story itself or use it as part of the framing for the story.

Before you finish a story, have someone else read it. When you read your own story, you are also hearing your own inflections on words and tone of voice. Your readers will only have the words, and will hear their own inflections as they interpret those words.

All stories rely on the listeners’ ability to fill in the blanks using their own experiences and imaginations. In Chapter 2 an audience picked up small cues from Kevin’s Tokyo story and used their own experience to fill in the gaps in the story and re-created it in their mind.

The IBM Research Knowledge Socialization Project (www.research.ibm.com/knowsoc/) talks about how stories “draw on common truths to convey more information than is obvious.” One of the ways a story engages the audience is by providing opportunities for them to build a rich picture, with much more total “knowledge” than what is actually said (or written).

One of the tricks to writing a succinct story is to make use of your ability to pick up on social and cultural cues. Of course, this relies on knowing your audience and being sure that they will extract the same information from a story that you put into it.

In her chapter on “Storytelling and Narrative” in The Persona Lifecycle, Whitney followed the IBM project’s example and looked at what information is suggested by even a very short fragment.

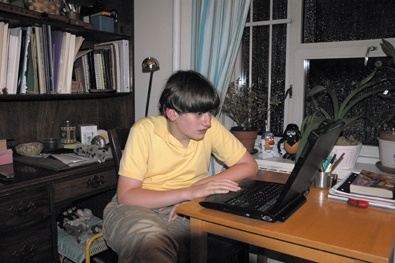

Tanner was deep into a Skatepunkz game—all the way up to level 12—when he got a buddy message from his friend, Steve, with a question about his homework. He looked up with a start. Almost bedtime and his homework was still not done. Mom or Dad would be in any minute....

Here are some things we learned about Tanner in just 53 words:

He is a kid (he still has homework and a bedtime).

He is an avid computer games player and good at it.

He has friends who also use the computer.

Getting a message is an everyday way to communicate.

He is probably on a cable modem or some connection where it does not matter how long he stays online.

He is probably playing in his room, or somewhere his parents cannot see him and watch exactly what he is doing.

We might be able to infer that his family is comfortably well off.

You can unpack any story to see what cultural or social assumptions it relies on and what details it communicates implicitly. When you craft a story, you can use those assumptions to keep the story short, focusing on the details that are important to the point of the story.

Stories don’t have to be just words. As a friend put it, “Would it kill you to have an illo or two? Even if storytelling is largely auditory, some of us are pretty visual learners.” He went on to point out that there are ways to create illustrations easily and cheaply.

We are not talking about drawing representative pictures or fabulous visual designs, although good graphic skills can be helpful. If you are one of the many people who think you can’t draw, stop worrying. As Dan Roam, Scott McCloud, and many others have pointed out, visual thinking is not about drawing, but about thinking. The Web comic xkcd is another good example. It’s composed almost entirely of stick figure drawings and other simple line illustrations.

If you are already a visual thinker, this kind of storytelling may come naturally to you. In his book, The Back of the Napkin, Dan Roam calls people who seem to want to leap up to a whiteboard and start drawing “black pen people.” He contrasts them with people who are comfortable with visual stories but don’t think they can draw and those who aren’t really comfortable with using pictures at all.

One way to work around a lack of drawing skills is to use a tool. In an article in UXmatters, Mike Hughes talks about how he uses comics to end a weekly project summary and says that they help him “condense complex issues and also ... communicate them in a humorous, but illustrative way.” As Mike himself admits, he is not a polished artist: he uses a free online tool called Make Beliefs Comix to get past his lack of drawing skills. You can see an example in Figure 15-2.

“This comic was part of a weekly report that informed the team we would be conducting a specific study shadowing users. It gave me the opportunity to remind researchers that we need to stay out of the experience we are observing. Portraying the user as playing Solitaire during the study (an authentic activity but one we never get to see) was also a gentle reminder that we never truly get to observe the user unobserved.”

—Mike Hughes

It doesn’t require a lot of drawing skills. But you do have to think carefully about what you are trying to say.

Figure 15-2. Using comics for team communication: www.uxmatters.com/mt/archives/2009/11/visual-methods-of-communicating-structure-relationship-and-flow.php.

Comics and cartoons are gaining in popularity as a way to tell a story or share a design idea.

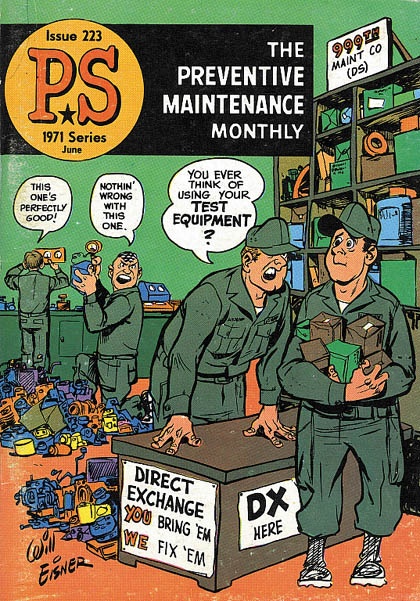

This idea isn’t new. Comics have been used to tell stories for many years. They are often used as a way to present longer or more complex stories in a simpler, more concise format. The “classics illustrated” comic books from many different publishers retold literary classics in comic format. Even the U.S. Army publishes PS magazine (Figure 15-3), which uses illustrated stories and comics to communicate basic safety and mechanical tips.

Figure 15-3. Cover of PS magazine from June 1971 from the VCU libraries: dig.library.vcu.edu/cdm4/index_psm.php.

Artists who worked on the publication included popular comic book authors such as Will Eisner. The visual style of Preventive Maintenance Monthly has changed over the years to keep up with the current style of comic books.

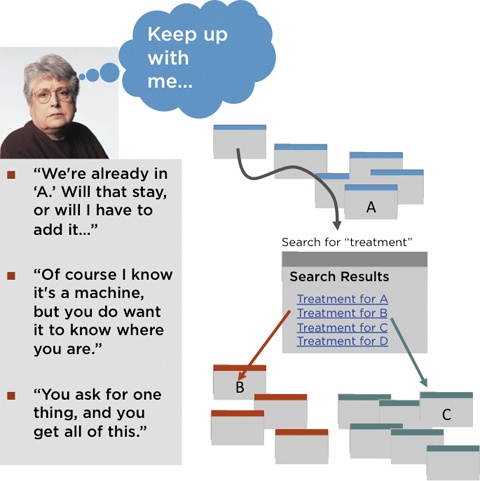

You can also use speech or thought bubbles in photographs to show what people said (or thought), as shown in Figure 15-4. (If you are using pictures of real people, be sure that you have their permission to share their image.)

Figure 15-4. This image from a usability report combined a collection of quotations with the thought behind them and the context for the comments. The photograph is from an image library to avoid using images of the actual participants.

The attraction of these kinds of visual stories may be the pictures, but they also present a complex topic in just a few words.

Wireframes and prototypes are common techniques for showing the interactive flow of a product: how users will navigate from screen to screen and what they will see on each one. Storyboards can communicate a broader view of the interaction to show context and events.

You can use storyboards to think through a design problem or show how the product will answer questions that people may have as they use it. These are a little different than wireframes or even interactive prototypes. Like comics, these storyboards combine visual images with a chronological sequence and captions or words spoken (or thought). They can illustrate a complete task or allow you to show a user’s thoughts and reactions to the product, as the story about Flow Interactive in Chapter 8 does.

Another role for visual storytelling is to make the imagery in a story more concrete. The audience can zoom in to the detail or pull back for the big picture. Visual stories can be unpacked just like verbal stories can.

Think back to the story about Tanner:

Tanner was deep into a Skatepunkz game—all the way up to level 12—when he got a buddy message from his friend Steve with a question about his homework. He looked up with a start. Almost bedtime and his homework was still not done. Mom or Dad would be in any minute....

Look at the photograph in Figure 15-7. Does it support or contradict this story?

The image gives fewer explicit details. For example, you don’t know the boy’s name, or his friends, or whether he has parents, and you can’t see what he is doing on the computer. But you can see a boy of a similar age to the text, using a computer. You can see that he is in a city, at night, high above the street (by the lights outside the window). And you can infer a social setting:

A private space for the boy to work unsupervised

Computer is readily available

A comfortable, middle-class home

The present day

A western culture

As with written stories, you can use visuals to add context and cultural background to the story. The photograph in Figure 15-7 reinforces the context suggested in the Tanner story. You can also use an illustration to add a twist or a surprise context. Imagine if the photograph of the Tanner story showed a boy in a very different cultural context.

Whether your story is entirely visual or adds illustrations to reinforce the words, visuals add depth to any story.

You can use a comic style to show conversations directly, suggest time lapses in the action, and show sequences of events.

Photographs add context, placing the story in a specific place or cultural setting.

Simple diagrams can show sequences, infer relationships, or highlight details.

A few years ago, we would have said that video and multimedia were not widespread enough to consider carefully, but with the rise of YouTube (and other online formats for presenting video or multimedia), video can be an effective way to share stories.

If you are thinking about using video, however, you have to do more than just read a story into the camera. One of the challenges of using video is that film and television are so pervasive that most of the world has a clear sense of what they consider to be quality video. Just turning on a camera and pointing it is just not enough.

As with oral storytelling, video storytelling communicates on multiple levels. It includes the words of dialogue or narration, the primary and background objects in the frame, the primary elements of sound, and any secondary or ambient sound, which can include music. This is all blended together for the audience.

Some video stories use some of the same simple ideas for creating visual stories, with a sound track and animation. A new trend in Web sites that promote new products (or ideas) is the use of video instead of text to explain how they work. This style of documentation not only blends spoken words, written words, and images of the concept or interface in action, but it can also reveal more about the experience than simply how the product works.

New Google products, like Google Voice, are often released with just one page describing what it is and how to use it—all of the explanations are short videos.

The instructions for adjusting the settings for multi-touch gestures in Apple’s OS X consist of a video demonstrating multi-touch gestures. Duh.

Starfire, which we talked about in Chapter 1, created a scenario in a video to show how new technologies could change how you interact with computers.

A company called Common Craft creates video explanations that tell short stories about how people use a product. One of their samples is Twitter in Plain English (www.commoncraft.com/Twitter).

Type the name of almost any new consumer electronics product with the word “unboxing” into a YouTube search to see more examples. Unboxing videos demonstrate the experience of first receiving a product, taking it and its accessories out of its box, and often setting it up and turning it on.

Each of these examples uses video to explain something technical and set it in a context so that you can understand why you might use the product. Twitter in Plain English is particularly effective at putting a human face on an experience that is difficult to explain before trying it.

Simply reading a script in front of a camera can be deadly boring, unless the words being spoken are incredibly interesting and you are an especially good performer. However, for most people it is natural to start composing a video by first composing the written word.

As you create the script for your video, you should keep in mind some of the different elements of the cinematic language. While video production is beyond the scope of this book, you can think about how to use these video elements as part of your story ingredients.

Camera: The camera provides the visual perspective. This includes how subjects are framed, how the camera moves from place to place, and how to light subjects to visually separate them from the background. In the visual language of film, there is implied meaning and emotional effect associated with various camera angles. Think about the films you have seen for inspiration and a style that will create a good visual interpretation of your written story.

Time and Space: Video is a temporal medium, meaning that things happen and develop over time, just like they do when telling an oral story. Video also uses the space of the frame. Things can come in and out of frame from the sides, and action can take place across the entire video frame, as well as forward and back within the frame, not just front and center. In a video story, you can use time and space to emphasize points and make the story more interesting, similar to how you would use your voice in an oral story.

Audio: The audio can be as simple as text read by an off-camera voice, but it can also include music, sound effects, and on-camera sound. People’s standards for audio are fairly high, so you have to consider what audio you want to include and how best to record it.

Editing and Rhythm: All stories have a rhythm, whether they are spoken live or recorded. In a video, you have the pacing of the narrative, as well as three other rhythmic lines—visual, aural, and editorial.

Visual rhythm is the rhythm of what you see, such as the swing of the arms and legs of someone walking down the street.

Aural rhythm is the rhythm of what you hear, which includes speech, as well as other sounds, music, and silence—often the most important effect.

Editorial rhythm is the rhythm of video editing, including the frequency of cutting from one camera angle to another, the use of point-of-view camera angles, how a cut happens in relationship to on-screen action, and if cuts are continuous or discontinuous to express jumps in time or space.

In the same way that we suggest practicing an oral presentation or having someone read a written story, having someone watch an early version of your video will help you see if any rhythmic elements are distracting from the story.

Video does not have to involve a camera. With the many graphic tools available, you can tell effective stories without the complexities of a live “shoot.”

One example is the software Photo to Movie (www.lqgraphics.com/software/phototomovie.php). It can take images and glide smoothly across them, fly and spin over them, or zoom in to a small region. The result is a QuickTime movie that you can then narrate, add music to, or manipulate further with other software tools. If your work involves photos taken in the field, product design illustrations, or prototype sketches, you can turn them into video and then add your script as voice-over. With only slightly more sophisticated tools, you can add overlay graphics to help tell your story.

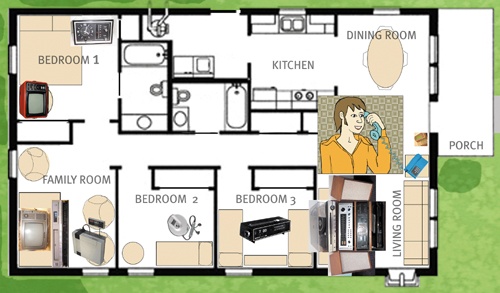

Kevin produced a number of animations for the “Learning from a tough room” story in Chapter 12. The image for one of them is in Figure 15-8. The animation showed home electronics of the past, as an introduction to ideas for how electronics might be used in the home in the future.

To create this animation, Kevin started with a large image of the layout of a house. He placed images of different household electronics on it: hi-fi, telephone, clock radio, B&W TV, etc. The animation flew around the house, swiveling around the path, and zooming in on the individual elements as needed. A narration explaining the connection between all of the elements was added later.

Reports and other deliverables are part of the work of most user experience designers.

Two obvious places to use stories are in user research and usability reports, as well as any deliverable that connects a design to user activities.

You may already be using a form of stories in your report, including quotes from users or brief anecdotes from your research. And you may find that thinking more consciously about using stories makes your reporting more effective. Two things we heard in our discussions about using stories in user experience reports summed this up for us:

“I didn’t think I used stories, but now I see that I do this all the time. I read out quotes or re-enact what I saw, describing what people were looking for and what happened.”—Lara Keffer

“One of the things that holds us back is the way we frame our presentations as ‘research reports.’ This influences their structure. Really, we should not be trying to just report on data, but to tell a story.”—Daniel Szuc

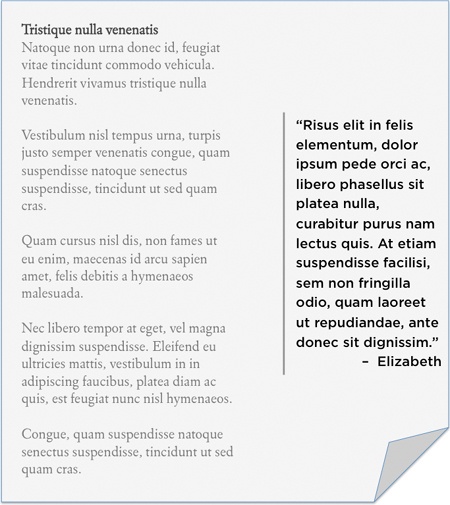

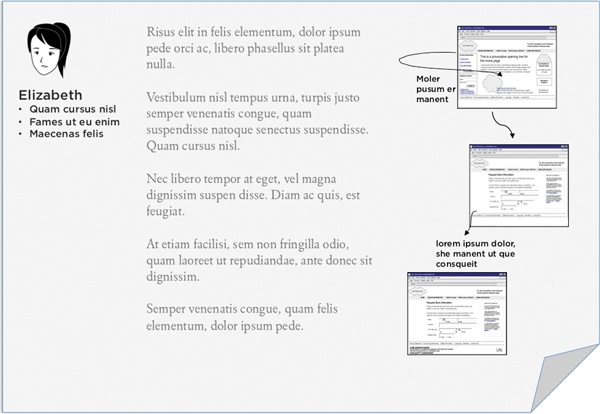

We’ve seen many reports that include quotes from users to support important points and help bring the research to life. Figure 15-9, Figure 15-10, and Figure 15-11 show various layouts that you can use.

Figure 15-9. If you include stories within the body of the report, you can use a layout or visual style to distinguish them from the rest of the text.

Figure 15-11. If you have photographs or screen shots, you can add talk balloons around them to represent the voices of those users.

You can also be more elaborate, introducing the person the story is about and illustrating it with photographs (of user research information) or screen shots (of an online experience).

An example of this is the story from Chapter 7 about how users wandered off track while looking for cancer information. The combination of screen shots, explanations of the interaction, and quotes from the users helped tell the story of how and why users got lost. Figure 15-12 shows what it might look like on a page.

Figure 15-12. This mockup shows a story illustrated with screen shots and a brief summary of the user characteristics.

You could do the same thing with video clips from a usability report, either telling one user’s story or combining several different people to show a pattern of interactions or problems.

These stories or story fragments can become part of the shared culture of the team. The story at the beginning of Chapter 1 about Priti, the woman who ended up selecting the wrong course for all the right reasons, is one that has become a shorthand for that team.

However you include stories, story fragments, or quotes, you must be sure of one thing: that the story supports the point you are trying to make. It’s no good putting together a collection of juicy stories if they don’t help the audience understand your point in a richer way.

If you deliver a report in person, you have another chance to use stories.

Your company culture may be more tolerant of stories in a presentation than in the formal report.

You can use oral storytelling to expand and illustrate points in the report.

All of the points we made before about paying attention to the audience apply here. You have to decide how many stories you can incorporate into a report and how much you can rely on them. Your colleagues may not have the same level of interest in the details of the research. You will have to decide how to engage them and win their trust for learning from stories, in addition to “harder” data.

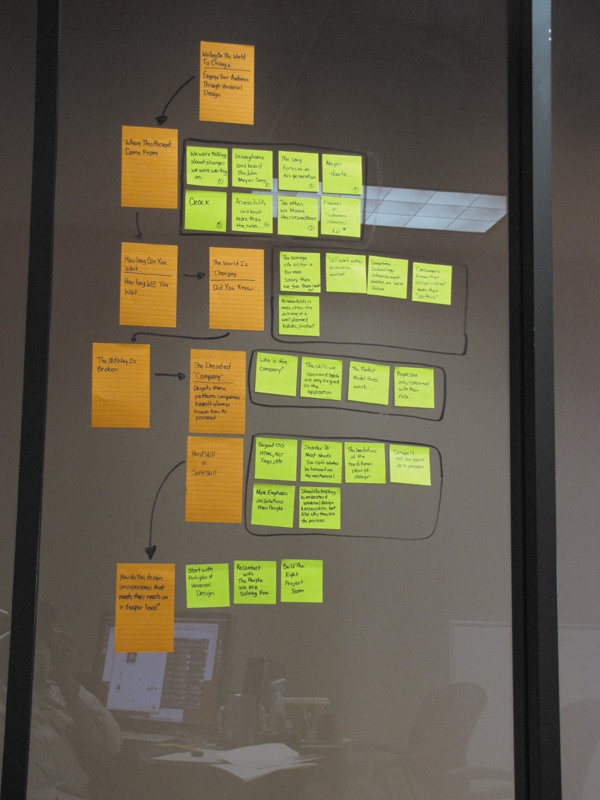

Presentations have a bad reputation as a boring sequence of bullet points, with someone droning through the information. Edward Tufte has even written an essay bemoaning The Cognitive Style of PowerPoint as a wasteland whose rate of information transfer approaches zero. Doug Zongker’s humorous presentation at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), called Chicken chicken chicken, reduced an entire scientific presentation to a single word www.youtube.com/watch?v=yL_-1d9OSdk and isotropic.org/papers/chicken.pdf. Do a quick search for bad presentations, and you’ll find hundreds of examples of how not to engage the audience.

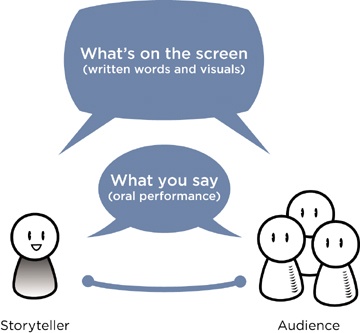

What makes presentations so challenging is that they combine both oral and written storytelling. You are giving a live presentation to a real audience. Presentations have a storyteller (you), an audience, story material (what you say), along with written and visual elements (what’s on the screen, such as PowerPoint).

Most poor presenters just start with something like a classic research report outline, and then they work through their material in a chronological order. Of course, like any other story, you have to start with the audience and what you want to communicate to them.

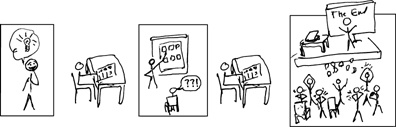

The trick is to think about the whole presentation as a story. You have something to say, and you need to present it in a way that will engage your audience. It’s the Story Triangle again, as shown in Figure 15-13.

Figure 15-13. The Story Triangle for presentations has two story forms working simultaneously: the oral story and the visual one.

Your goal is to help the audience create the story (or hear your point) for themselves. A presentation is not only a story, but it also contains stories. When you are dealing with a story-within-a-story, you will probably find that relying on a clear, simple story structure (see Chapter 14) will help you—and your audience—stay on track.

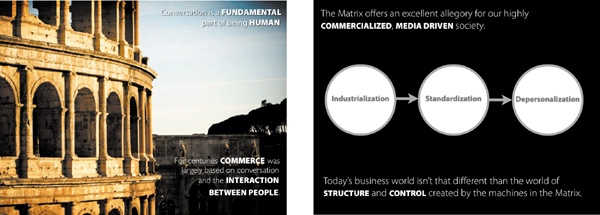

As you can see in these samples of Kelsey Ruger’s slides (in Figure 15-15), the visuals are not a literal transcription of what he says in the presentation. Instead, they provide imagery along with a few words to reinforce the key point. Audiences are listening to your presentation in multiple modalities, in this case, visual and auditory. These modalities do not have to provide the same information all the time. In fact, it’s usually more interesting if they don’t.

Figure 15-15. You can see the slides for this presentation on SlideShare: www.slideshare.net/themoleskin/crucial-conversations-in-social-media.

This chapter has focused on the different ways you can share a story: telling a story orally, writing a story, presenting visual stories like comics and storyboards, and showing multimedia stories. We’ve also looked at how to use stories in two business formats: the report and the presentation.

Each medium for telling a story has strengths and weaknesses:

Oral storytelling allows you to create a rich experience, interacting directly with the audience. This medium can be woven into meetings, report presentations, or design brainstorming sessions. Stories and story structures make formal presentations more engaging.

Written stories allow you to shape a story and share it without a performance. The readers can skip forward and backward to review the story. Stories in this medium are easy to integrate into reports, illustrating important points or sharing user voices and actions you have collected.

Visual storytelling lets you share a conversation, show an environment, and provide rich cues for the audience’s imagination.

Technically mediated story forms like video and multimedia are informed by oral storytelling practices and visual language, using their own techniques and language.

Oral storytelling

Improving Your Storytelling, Doug Lipman

The Power of Personal Storytelling, Jack Maguire

The Storyteller’s Start-Up Book, Margaret Read MacDonald

Storytelling and the Art of Imagination, Nancy Mellon

Storytelling performance

National Storytelling Festival: www.storytellingcenter.net

Local storytelling festivals and events: storynet.org

The Moth: www.themoth.org

MassMouth: http://massmouth.ning.com/

Visual stories

Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud: scottmccloud.com

The Back of the Napkin, Dan Roam: www.thebackofthenapkin.com

Digital storytelling

The Center for Digital Storytelling: www.storycenter.org

Hillary McClellan’s Tech-Head: www.tech-head.com/dstory.htm

Presentations

The Cognitive Style of PowerPoint, Edward Tufte: www.edwardtufte.com/tufte/powerpoint

Beyond Bullet Points: www.beyondbulletpoints.com

Pecha Kucha: www.pecha-kucha.org

There are many mediums for stories, both in person (with oral storytelling and presentations) and in a written, visual, or multimedia format.

Oral storytelling is a performance, told in real time to an audience. It offers direct interaction with the audience in a dynamic, sensory, and immediate way. To tell oral stories well, you need to develop your own performance style and practice telling the story many times.

Written stories enable you to reflect and edit, and let the audience experience them at their own pace. Written stories can be included in reports and other business communications.

Visual stories let you share imagery and context without lengthy descriptions.

Multimedia can bring together visual, oral, and written storytelling techniques.

Presentations also blend story mediums, mixing the richness of a performance with words and visual imagery.