In this chapter, we reach the structure—the organization of events—of the story. In the previous two chapters, you have seen how you can tell a story from different perspectives or change the way you tell it to different audiences. Here, we will look at the elements of plot and structure.

The structure is the framework of a story. It’s the underlying skeletal pattern for the story.

The plot is the arrangement of the events of the story, the sequence in which those events are revealed to the audience.

Story structure and plot are the path to bring the audience into the world created by the storyteller. When the audience can enter the story through a clear structure and plot, they can pay more attention to the story’s larger themes and higher-level points, and are less likely to be distracted by logic and rational analysis. They can listen to the emotional subtext of the story, and be coaxed into its influence. They can “get it.”

Storytelling is one of the oldest art forms. We can imagine ancient hunters sitting around the communal fire at the end of the day, dressed in the skins of their kills, telling stories of their exploits. People haven’t changed all that much: we still care about our families, our work, and moving forward with our lives, so some aspects of our stories haven’t changed that much either. But even within a familiar structure, each story has its own pacing, images, and context. Most stories follow familiar structures. Even if there are twists and turns in the plot or surprises in how the ingredients are assembled, the basic structure is often a familiar one.

Some story structures are very simple:

A boy meets a girl, they fall in love but are kept apart, and then finally they find each other again.

A person is given a mission and sets out to fulfill it with the help of a band of friends. They overcome obstacles and eventually reach their goal.

Some structures are more complicated, such as stories that are in layers, each one revealing a little more of the details until a secret or underlying truth is found. Working with a familiar structure will help you build your story, and it will also help your audience understand it. You can focus on using the story to make a point.

The underlying structures of stories are found across many different cultures and languages. Although story scholars’ approaches and taxonomies differ, they all look at the structure of a story as a journey that the characters take. Story scholars like Vladimir Propp and Joseph Campbell have studied the way stories have been told around the world and throughout time. Campbell and Propp’s work have influenced Broadway and Hollywood. Campbell, for example, was an important influence on George Lucas as he developed Star Wars.

Campbell is most widely known for his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces. In it, he traces the hero story structure across cultures and across centuries, showing how consistent and universal it is. Many of his examples are drawn from myths. Joseph Campbell’s work provides a detailed cross-cultural analysis of the hero’s journey as it appears in stories from many cultures and languages. Campbell was especially fascinated by the way an individual’s life story echoed the mythic hero’s journey.

In the early part of the twentieth century, Propp catalogued and analyzed stories in The Morphology of the Folktale. Although Propp analyzed Russian folktales, his work applies to many types of stories and illustrates a relatively simple way that stories can be deconstructed. Propp identified 31 “functions” of fairy tales—classifiable actions that characters can take. He found that they occur in a consistent order, as found in Campbell’s later work, but that the selection of functions varies from story to story. The combinations of these actions become grammar for story structure—a framework for how the story develops.

Propp’s functions also follow a character’s journey, with different events that may happen along the way. They are written in the language of fairy tales, but with a little imagination, it is easy to see how they might apply to any situation or life journey.

The first functions set up a situation in which someone needs to be “rescued” or where there is a problem to be solved. They include warnings, ignoring those warnings, reconnaissance of the situation, trickery, deception, and outright villainy.

In the middle of the story are a group of functions in which the hero leaves home to correct the situation and is tested. He (or she) may receive help from a magical agent and have to search for the villain, but ultimately confronts and overcomes the problem.

Finally, the hero returns home (or is rescued). The hero may not be immediately recognized for his efforts, having to complete one more task before being rewarded.

The selection of functions determines the structure of the story. Propp believed that functions could be omitted from a story, but that they always appeared in the same order. Contemporary narrative scholars find Propp’s work particularly interesting as the basis of computer models for constructing stories. You can look at one such model, called the Proppian Fairy Tale Generator (www.brown.edu/Courses/FR0133/Fairytale_Generator/gen.html). We are not suggesting that you use a computer program to create your user experience stories, but these research experiments show that it is possible to create a plausible narrative with a computer program. You may find that using linear, logical structures as a framework is a helpful way to start constructing your own stories.

Both of these scholars looked at the patterns of stories in the same way that Christopher Alexander’s A Pattern Language deconstructed architecture into a set of structures that could be rearranged and reused in endless creative ways.

Architecture is a good analogy for the function of structure in crafting a story. When you see a large building being built with its structural steel complete, you have some idea of the general shape of the finished building: how large it will be, how many floors, and so on. Even without seeing the color or external materials of the building, you can still get some sense of what the building will be like, and even how you might eventually navigate through it. (That is, with the possible exception of a building by architect Frank Gehry, with his typical use of fantastic superstructures of planes and shapes.)

It’s the same for story structure—it’s a framework for the finished story, before you add ingredients like character, context, or even the details of the plot. We’ve drawn on this tradition of analysis to suggest some story structures that you may find useful as you create your own stories.

There are three main reasons to create a strong structure for a story.

It helps the audience. When the audience recognizes the structure, they have another level of understanding of the story. They can listen to the details of your story more carefully, once they have a good expectation of how the story will be told; they don’t have to waste time speculating on the direction of the story.

It helps the author. Story structure is a navigational device, helping you figure out what’s next or what’s missing as you create a story.

It helps the story. It can help move a story from a vague idea to something more solid, suggesting ways to organize it into a beginning, middle, and end.

Story structure provides familiarity to the storytelling process. But that doesn’t mean each story has to be the same. You can play with the structure, following it closely or deliberately violating the audience’s expectation with a twist. Without the platform of the structure and the expectations it creates, the twist has far less impact.

The familiarity of story structures can also provide comfort by giving the audience landmarks to use as they navigate the story. This can be particularly important if the topics of the story are unfamiliar or challenging. Familiar structural hints will help them grasp the story more easily. They may look for a wise mentor who shows up to help the hero or for flashbacks that illuminate events in the present.

User experience stories aren’t on the momentous scale of an epic. And we aren’t claiming they are great works of art. But UX stories are still about things that make a difference in the lives of real people. If you use a structure that is familiar to your audience, the context can add resonance and depth to a prosaic situation.

We talked in Chapter 12 about ways to let your audience see themselves in the story. In Chapter 2, Michael Anderson’s persuasive story, “Using Analogies to Change People’s Minds,” used analogies to allow his audience to relate their current situation to “a different story.” Any story about an outsider who arrives to solve a problem that is blighting a community can be cast as Beowulf slaying the monster Grendel—that is, fixing something that is broken in a user experience. In fact, many user experience stories have the new product (and the people behind them) as implicit heroes. Waiting For the Bus in Chapter 13, the story about Sandra and RideFind, is a story of someone rescued from distress.

From various collections of story structures, we have selected a few recognizable story structures that are useful in telling stories in user experience design. We offer them here as starting points for your stories. These structures are:

Prescriptive: Structural templates that allow you to fill in the blank

Hero: Using Joseph Campbell-inspired hero’s journey elements

Familiar to foreign: Using a different journey of sorts that begins with the comfortable and then stretches into the less familiar

Framed: Stories that appear to begin and end the same way

Layered: Using layered images to build a story experience

Contextual interludes: Using diversions of physical or emotional details to add an extra dimension to a story

A simple, straightforward story structure for user experience stories is prescriptive. All it requires is a fill-in-the-blanks approach, using whatever contextual details and outcomes are required for your application. Think of it as more of a logical argument structure that gets expanded into a story. Given X, if Y, then Z. To create a story with this structure you just need to figure out what elements in your project or environment satisfy the XYZ requirements of the structure. Dan North describes a prescriptive structure for what he calls Behavior-Driven Development:

Title

Given [context]

And [some more context]...

When [event]

Then [outcome]

And [another outcome]

By starting with the title, this structure immediately provides the audience with the subject matter of the story. It then requires some amount of context (where is this story, who are the main characters of the story, etc.), the major event, situation or problem, and finally the primary outcomes of the story, presumably the solutions.

This type of structure is widely applicable. While it’s easy to fill in the blanks, you should pay attention to making the chain of causality plausible—to making sure that the story makes sense. While any structure is by its nature simple, it is all too possible to create an overly simplistic story. For instance, the “Widgets for prosperity” story below makes such a broad claim that it is almost nonsense. It’s hard to imagine that an impulse purchase of a widget—no matter how low the price—could lead to prosperity.

All the elements of this story fit the structure. And while a bit overstated in order to make a point, the story itself is simplistic and would therefore be unconvincing. Here’s an alternative:

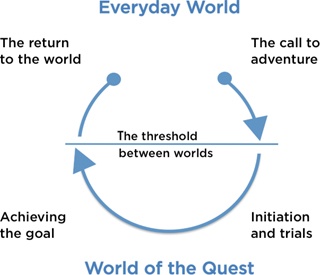

Many of the stories in this book have a hero—usually someone who has to overcome a problem. Joseph Campbell described this structure as a hero’s journey, and identified several steps in the journey. In his structure, part of the story takes place in the everyday world and part in the world of the quest. The journey completes a cycle from one to the other and back, shown in Figure 14-1.

Figure 14-1. The hero story structure is a cycle. The point where the story ends can be the beginning of the next story.

The call to adventure

Heroes start in the everyday world and receive a call to adventure. They usually resist at first, refusing to undertake the journey. (Think of the hobbits in The Lord of the Rings and how hard they tried to return to their comfortable life in Hobbiton.) A supernatural character (Gandalf the Grey) often comes to their aid and helps them take the first step on the journey. They may set out alone or with a band of companions (the Fellowship of the Ring). One of these companions (Sam Gamgee) acts as a window character—a reminder of life before the journey and how far the hero (Frodo) has come.

The initiation and trials

The journey is often described as a series of trials and setbacks, which the hero must overcome (filling most of the story). Heroes meet goddesses and father figures, and are helped through their adventures by their companions. Often, each companion has a particular skill or characteristic that proves critical to the hero’s success.

Achieving the goal

The second stage ends with the achievement of the quest (destroying the Ring at Mount Doom).

The return

Heroes must not only finish the quest, but also get out alive. They may need help to return to the world, with the object or knowledge of their quest. Ideally, they learn and grow from their mission and so return a changed person, ready to share their experience.

Hmm. Quests. Supernatural characters, goddesses. This may not sound much like user experience design, but this structure can be used for simple and prosaic “quests,” as well as for epic and mythical ones. Here’s a story that uses the heroic structure, elaborating on the short realist tale from Chapter 13.

Let’s look at how this story follows the hero’s journey.

The call to adventure

Initiation and trials

Trials and setbacks—slipping and falling, plus the temptation to give up

Achievement of the quest

Trying the RideFind number

The information arrives

Return to the world

Making use of her new knowledge—telling the other person about the bus

The arriving bus will take her to work

You could shift perspective and tell this story from the point of view of the network manager who keeps the RideFind service running, from the perspective of a bus driver, as the story of a band of intrepid commuters, or even as the observer coming up with this new idea from the trials of those commuters.

These stories take the audience on a journey, starting with something familiar and comfortable, but then taking them toward the unknown. As with the hero structure, this structure starts in the “real world”—the world the audience already accepts. The goal of the story is to draw the audience into a new place, helping them make the transition by showing parallels between the familiar and the foreign and possibly illuminating something new about the familiar world.

Many TV commercials use this structure, particular for financial services and other nontangible products that may seem foreign or frightening. By setting the story in a familiar setting, the ads suggest that their service is also simple, homey, innocent, safe, smart, or practical. Like most commercials, these stories are compact and efficient, lasting just 30 seconds.

A TV ad from Zurich Financial Services called What if? includes four short scenarios, each of which takes a common situation and asks “what if” to show an uncommon result.

TV ads from Ameriprise Financial, starring Dennis Hopper, reverse this concept to show the familiar in the foreign. Hopper makes impassioned points standing alone in the middle of an unusual setting (a field of flowers, a deserted beach, a salt flat), followed by a sequence of familiar daily life images of people presumably acting on their dreams.

Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland is a longer example of this structure. Alice first appears in the story as a bored girl sitting on the bank of a river in the English countryside. So far, pretty mundane. Then a white rabbit runs by. At first this is nothing amazing or unusual, except that the rabbit pulls a watch out of his waistcoat pocket and says, “Oh dear! Oh dear! I shall be late!” Since she has never seen a rabbit with a waistcoat and pocket watch, this sparks Alice’s interest, and she follows him down the rabbit hole. Once inside Wonderland, she speaks with animals, a strange cat appears and disappears in front of her, and she meets a royal family of playing cards. All quite ridiculous, fantastic, and enjoyable, especially in contrast with the prosaic opening scene in the English countryside.

Starting in the familiar and moving to the less familiar or foreign is a common way to introduce new concepts to an audience. Consider this user experience story that could have been used in the early 1990s to drive product sales.

Like most seemingly fantastic stories, this one has more than an element of truth. It is based on a story we found in the news. It begins with a very familiar scene—a lawyer on a sales trip, but with the main character placed in a different culture. The twist on the structure comes when the lawyer draws on his own experience to come up with an idea that can be applied to this new and different culture.

Familiar-to-foreign is also the structure of many stories that demonstrate new technology or design ideas.

In the framed structure, the story appears to begin and end in the same place. It wraps around itself, and like Dorothy back in Kansas, finds its way back home, but with a different realization or understanding from having taken the trip. So while the beginning and ending of a framed story are similar, it is their difference, however slight, that gives the story impact.

This story is so simple that if the structure were not called out, it could be easily overlooked. It’s built from an anecdote, a simple idea that you might discount all together. “That idea? Oh that’s not a story!” Yeah, it is—or it can be.

Don’t confuse framed stories as defined here with “a story within a story.” While these two story structures are similar, the story within a story has interwoven stories, each of which can stand on its own and illuminate one another. Our framed stories are simpler and are composed of story fragments or images that only give a sense of a full story when put together.

There are three common variations on the framed structure: Me-Them-Me, Here-There-Here, and Now-Then-Now.

This structure begins with some aspect of yourself—something you like or are good at. Then it turns to another person who does it differently (better or worse) or brings a different perspective. And it ends by returning to you.

This structure works particularly well for stories told in the first person, but it can just as easily be told in the third person. The main character might be someone you use as a lens for the story or someone that your audience will identify with. The next story is a Me-Them-Me frame about different ways to shop, told in the third person.

In this structure, you start in the present, with a specific event or image. The important thing is that it be in the present—“now.” Then it turns to a related detail from the past to show how it affected the character then. The story ends with a return to the present, but with an echo of the past, changing the way the character perceives the new “now.”

The Now-Then-Now structure is a nice way of illustrating the main character’s relationship with the world without focusing on the relationship. As the story jumps back and forth in time, the audience sees how the main character connects with the world. Some things will remain constant, but others will change.

Many user experience stories describe a new (or updated) relationship with technology. This structure can show how basic needs stay constant over time, but can be met in new ways. The “Mechanics of Writing” story is an example of this use of the Now-Then-Now structure.

Now: When working on this book...

Then: Back in the 1980s...

Now: The mechanics are easier...

Other examples are a doctor who still needs to treat the patient, or the delivery person who still needs to deliver packages on time. Their connection with the world is the same. But current tools can meet those needs in a better way than those they used or knew 10 or 20 years ago.

In this structure, you start with a location, where you introduce the main character. This might be “home.” Then select some other place, either far away or seemingly far away. Finally, like Ulysses, you return home. Focusing on distance can be a powerful way of talking about other cultures. This structure is easy to reverse to There-Here-There, too. Here’s an example inspired by an Italian friend of Kevin’s from a number of years ago.

Layered stories are told as tiny images one after the other. Very little may happen in the plot. Instead, the story is revealed through the details in the images. Each image builds on the previous one, adding layers that build up into a full picture.

This structure is a good one to spark the audience’s imagination. It puts their natural story interpretation ability to work as they think about how all of the layers fit together. You can create a surprise ending by using the last image to suggest an unexpected interpretation of the sequence.

There are advantages and disadvantages to this structure. It is slow, but can be a potent method of telling a story. The story doesn’t have to give away where it’s going early (as in this example). If the images are engaging enough, then the audience is less likely to notice a lack of plot and be willing to focus instead on the images and their residual feelings. It is likely that the audience will remember their feelings from the story more than specific story points. Therefore, use this structure when you specifically want an emotional, as opposed to logical, response to your story.

This structure will not always work for every audience. Some people will understandably want you to “get to the point.” Others will be patient and wait for the story to evolve. One way to address the needs of the get-to-the-point audience is to give them more to-the-point context either just before or after the story. You could start or follow the story example above with a statement that provides context.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is an often slowly progressing, incurable lung disease that blocks airflow, making it increasingly difficult to breathe.

You can use the layered story structure as one element in a larger structure—for example, putting it into a section of a story where you want an emotional response, nesting it within the logic.

One of Kevin’s performance stories, “Tomato Paste,” uses a layered structure. It starts with a list of three things Kevin knows about tomato paste. Each element builds upon the previous element, growing in complexity. The first paragraph is fairly simple; the second is slightly longer and more involved; and the third is quite involved. The story does not give away where it’s going and purposely leaves out explanatory details that would reveal its intended direction.

You can read more about this story on the book’s Web site and see a video of Kevin performing “Tomato Paste” on YouTube: ![]() www.rosenfeldmedia.com/books/storytelling/blog/tomato_paste.

www.rosenfeldmedia.com/books/storytelling/blog/tomato_paste.

Detailed descriptions of context can also be used as a structural element in a story. Like a layered story, they allow the point of the story to emerge from a collection of details, without much action or plot. Contextual interludes can help you show relationships in what may seem like scattered collections of physical or emotional details that form the context for the story. They work in two ways:

The contextual interludes connect the audience to the tangible, like sensory elements, or to personal experiences. They are often built on a close telling of sensory elements.

They are a break from the action of the plot. This can be particularly important in stories that are trying to communicate the textural details of an experience.

The following example continues the Motown story from the section on context as an ingredient in Chapter 13.

This contextual interlude could be part of a larger story about media personalization or about the portability of electronics. That story might show how an MP3 player liberates music from a single location, or compare the physical texture of the old record player to the feel of a new device.

You can use contextual interlude as a story introduction to a place or time before launching into the main, action-oriented part of the story. Or it can be an ending that adds emotional elements to an otherwise straightforward narrative.

Framed stories may use two contextual interludes to contrast the starting and ending state of the characters.

In a Here-There-Here story, an opening contextual interlude can introduce a cultural or geographic context, identifying details that are key to the experience.

In a Now-Then-Now story, the central part of the structure might draw on a factual or fictional historical or sensory context describing the sounds that can be heard.

Plot is the arrangement of the details of a story. It includes what happens in the story, in what order, with whom, and with what chain of causality. For many types of stories, it’s the plot that carries the audience from the beginning to the end and, hopefully, inspires them to ask the question you may want them to ask, “What happens next?”

Drawing the audience in and holding them is the power of a good story plot. Professional storyteller and teacher Loren Niemi puts it this way:

“The aim of plot and detail is to create unity, a singular thing of beauty which, when told or read, is forcefully present and inviting. When the audience hears or reads such a story, they enter its internal logic and geography willingly and find that it satisfies, sustains, and remains with them.”

—Loren Niemi, The Book of Plots

As with any other aspect of a story, the plot is crafted to capture and hold the audience. There are keys to determining the plot of a story:

Arrangement: The parts of a story can be arranged and rearranged by the storyteller. By controlling the arrangement of the story elements, the storyteller can engage the audience and shape their acceptance and understanding. For example, stories don’t have to be strictly chronological, even if the story is about a linear chain of events. For business audiences, it might be more effective to tell the end of a story first—to cut to the chase as it were. It’s OK to show them where you are going, since the path to that point doesn’t have to be predictable. But the arrangement of the events in the journey to the end of the story has to be clear and justified at every point along the way.

Plausibility: On some level, a story must be believable. That doesn’t mean that all stories must be factual, but they must ring true enough at every point along the way so that at no time does the audience stop listening and instead start thinking, “Is that true? Could that really happen? I don’t think so, but I’m not sure.” When they mentally (or perhaps worse, verbally) ask that question, you’ve lost their attention, and it may be hard to get them back. Plausibility is measured moment by moment, so what’s implausible at the beginning of a story may not be implausible if it occurs near the end.

The goal of some user experience stories may be to change the audience’s sense of what is plausible, opening up the possibility of new ideas. UX and business stories rely on plausibility. Plausibility breeds confidence and lowers feelings of risk. Take for instance the “Widgets for prosperity” story examples earlier in this chapter using Dan North’s story structure. The first example would not convince major project stakeholders on the viability of Acme Widgets in the marketplace. It simply doesn’t build from the starting point to the final conclusion. The second example is more effective because it builds from one “given” to another, taking small steps from the current state to a new one.

There is no one right way to put together the plot of a story. Once you have the events clear in your head, the best way to figure out the best story plot is to play with it. Here is an example:

This is a simple story with a simple structure. It’s a chronological chain from one event to the next—this happened, then that happened, then this other thing happened, etc. The first two sentences establish who the main character is and what problem or situation the character needs to address. The next four sentences show a first step toward solving the problem—looking to online dive shops—but then introduce another problem, of what size to buy. The rest of the story describes how the problems were addressed, with the final line added to spark the reader’s imagination. What would they have her do if she wanted a wetsuit? Lie down on a giant piece of paper?

The plot could be rearranged to focus on the interests of a particular audience. Leaving the major events unchanged, detail and emphasis would be placed differently. The first way of telling the story is probably ideal for product management, with its balance of just enough technical details to suggest how the idea might work and the focus on differentiating the site from others.

The same story might be re-worked to address the perspective of developers:

This is the same story, but told from a different perspective. Since gender is not important for this story, it is eliminated. Since the customer’s point of view is of limited value for the purpose of this story, those details are limited. A developer would be interested in how the various processes and algorithms connect together to create an end-to-end service. Therefore, more of the details of those processes are included—much more than in the previous version.

Structure and plot go hand in hand. Choosing a structure for a story will shape its plot and help you see which details fit and which don’t. Knowing even a partial arrangement of plot details will help you see what structure might fit the story best. Then you can use that structure choice to further guide plot details. Here are some examples, starting with a user experience story example, and then a story that is more general.

Here is a story for a technical audience of researchers and developers about using mobile technology to coordinate large groups to be at the same place at the same time.

This story is structured much like a TV product ad, since the story was for a fictitious new product. Most standard TV ads use a structure that starts with a context and problem, shows how the product beautifully addresses those problems, and then has some sort of “kicker” at the end.

The first two sentences of the story provide the context of the problem in a visual way: “... but they can’t click away a thousand bodies.” That image is used to impart a sense of power.

The next section of the story describes how it works. Because the purpose of this story was to get people to see the value of new technological features, the specifics of the interface are not important. There is no mention of menus, buttons, or service contracts. The details of both the features and the design are left to the audience’s imagination. The audience not only provides their own vision of the interface, but also determines whatever technology would be needed to do this. The story just speaks of the effect of the service, echoing the imagery from the earlier context.

The last sentence is the kicker—just eight words. A kicker is often a slogan, such as “We bring good things to life,” “Good to the last drop,” or “Melts in your mouth, not in your hand.” It can also be a word image that encourages the viewer to think, “Hey, they’re talking about me.” Or “I want my life to be like that.” “We use advanced technology to advance our society” may sound a bit altruistic, but the point is to highlight, for a technical audience, the power and influence of the technology. Particularly their own technology.

As you start to craft a story, try out different structures. Look at the ingredients you want to emphasize and choose a structure that will let you explore them with the audience.

A good structure and appropriate plot points will provide you with these areas:

Coverage: Does it address all of the facts without leaving out any inconvenient details?

Coherence and plausibility: Does the explanation the story provides make sense?

Fit: Is the story a good fit for the facts, or has it been forced into place?

Uniqueness: Is it a compelling explanation, or does it seem like there are many others that would work equally well?

Audience Imagination: Is the story loose enough for the audience to build their own details, or is it so detailed that there is no room for the audience to use their imagination?

One of the other benefits of working with a defined structure is that your story is more likely to be easy to retell. For you, this also means that you can learn the story well enough to adapt it to a slightly different audience as the need arises. It also means that others can retell your story. If your story is so clear that others are inspired to use it, then that is a measure of success.

Stories are made up of many elements. You can craft stories by carefully assembling all of the ingredients into a structure and a plot. This may feel a little mechanical at first, but as you gain experience, you will also gain a more intuitive feel for how to use these elements.

But a beautifully crafted story is something more than the sum of its parts. The many story parts described in this book are not recipes for stories or Lego pieces that fit together to create the perfect story, but paint colors and brush sizes. They can serve as guidelines to get you started, but the goal is to paint over the seams between the parts so that the audience experiences a sense of awe, not a sense of appreciation for the cleverly assembled story parts.

“Awe matters.” In their book Imagination First, Eric Liu and Scott Noppe-Brandon describe the work of scientist David McConville (www.elumenati.com). McConville employs 3D projection technology to stir the imaginations of climate change policy makers and school children alike. McConville uses awe to affect changes in thinking and understanding. When we as storytellers allow an audience to sit back and take in all of an image, a vision, an approach, or a world through storytelling, then we too are unleashing their capacity for awe. And the audience’s gratitude for that makes them ready and willing to learn and accept new ideas.

The Hero with a Thousand Faces by Joseph Campbell

Two descriptions of the stages of the hero’s journey: faculty.gvsu.edu/websterm/Hero.htm and www.mcli.dist.maricopa.edu/smc/journey/ref/summary.html

The Morphology of the Folk Tale by Vladimir Propp

Both Wikipedia (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vladimir_Propp) and Answers.com (www.answers.com/topic/vladimir-propp) have good summaries of Propp’s functions.

Dan North’s story structures: dannorth.net/whats-in-astory

The Books of Plots by Loren Niemi

The structure is the framework of a story. It’s the underlying skeletal pattern for the story, similar to other architectural or design patterns. The plot is the arrangement of the events of the story, the sequence in which those events are revealed to the audience. Look for the balance of structure and plot that helps you make a point effectively.

Useful story structures for user experience stories include:

Prescriptive: Structural templates that allow you to fill in the blank

Hero: Joseph Campbell inspired hero’s journey elements

Familiar to foreign: Begins with the comfortable and then shifts to the less familar

Framed: Stories that appear to begin and end the same way

Layered: A series of images that build a story experience

Contextual interludes: Details that add an extra dimension to a story