Now that you’ve collected stories, you have to select those to develop for use in analysis. These stories serve a purpose and must be more than simply “great” anecdotes.

A performance storyteller may start from a story that “just feels right” and develop it over many years, letting it evolve in front of different audiences. In user experience, that process often happens as you (and your team members) go through all of the user research material to understand what you have learned.

As you select and develop your stories, you have to consider both your audience and your goal. These stories must help you understand the user experience in a new way or help support your user analysis as you communicate with the rest of the user experience team, the broader project team, and management.

You (and your colleagues) are your first audience. Your first use of stories is to help your team understand what you have learned about users and their context. If you don’t find these stories useful and meaningful, no one else will either, because you won’t be able to use them effectively.

The process of selecting stories is iterative, just like any other analysis. At the beginning, you may notice stories that illuminate the problems you are working on. But, as you dive deeper into the analysis, you will find stories that point out new, previously unnoticed aspects of the design space.

The more often you work with the information, the easier it is to connect individual data points to make a coherent picture. You may find some of the stories you collected popping into your mind as you work on other parts of the analysis. For example, a story might be a great illustration for a quantitative data point, or it might provide the background to explain users’ attitudes about a product or task. For example, published research suggests that Latinos who are more acculturated—who have been in the U.S. longer, were educated in English, or speak English more fluently—often act as intermediaries in helping their families navigate the healthcare system in the U.S. With that data point tucked away in your mind, when you hear a user research participant talk about finding information for her mother, your ears should prick up. Perhaps there is a concrete story here that can help make the research more vivid.

This isn’t that different from any other analysis process. It can work both top down and bottom up. You may select stories to illustrate a concept. Or you may combine story fragments and other data points to draw a larger conclusion. (You have taken your notes in a way that makes it easy to find those stories, right? If not, go back to Chapter 6, where we have some pointers for writing notes.)

Remember that you may not find complete stories popping out of your notes fully formed. Often, you will have a collection of anecdotes, notes on behaviors, and imagery. These can be equally valuable as the building blocks for rich stories. Here are a few examples:

A user describes his system for storing information as “a junk heap—like my kids’ closets, with everything tossed in wherever it will fit”—and suggests that he needs “one of those consultants who organizes your closets.”

Someone else talks about “the laundry basket of junk on my computer—I just pick the newest things off the top and never get all the way to the bottom.”

During a usability test, participants seem to get lost in part of the program. They talk about how much information there is on the screen, using words like “cluttered,” “crowded,” “junk heap of valuable things,” and “overwhelming.”

A participant tells a story about losing information that she is sure she saved... somewhere.

Another describes her “perfect toy” as a “Mary Poppins bag that never gets full, no matter how much you put into it.”

These are all different viewpoints on managing the objects in our lives. Any one of them could be the starting point for a story, or you could combine snippets from different people into one story. If you have the data, you can go further and mix in the insights from metrics. For example, perhaps cluttered screens are making it harder for users to find information

What you are looking for are juicy stories: stories with plenty of texture, dripping with good detail.

Some of the signs of a juicy story are the following:

Stories that you have heard from more than one source. They don’t have to be identical, but when you hear similar anecdotes or ways of talking about an event, pay attention.

Stories with a lot of action detail. Stories describing the way things happened thoroughly are valuable because they offer more than an opinion or a quote. They capture a narrative sequence and can be the basis for further development as a scenario for how a product might be used.

Stories with details that make your user data easy to understand. Stories with a lot of contextual detail help anyone who hears them relate to the people they describe. These details might describe when, how, or why something happens. They might be a turn of phrase, a way of describing someone’s goals or actions, or an anecdote that just seems to sum up a type of person or event.

Stories that illustrate an aspect of an experience that the UX team is particularly interested in. They may not be your focus of attention, but you can always look for stories that have come up organically during any story collecting. If you know that your team is starting to work on a mobile interface, a story about how someone used your site through their cell phone will be particularly juicy at that moment.

Stories or story images that surprise or contradict common beliefs, yet are clear, simple, and compelling. These can be the hardest, because (like Ginny Redish’s story, A Story Can Deliver Good News...and Bad News, in Chapter 4), they may deliver bad news. However, stories can provide early anecdotal evidence that can suggest new design directions or new user needs.

Stories are most valuable when they help you explain something about the user experience in a way that gets beyond simple demographic facts or even complex data analysis. They should bring your data to life by grounding it in a specific context.

When you find a juicy story fragment, you can work with it to see if it develops into a useful story. You might start from a user quote or an anecdote and see if it still holds your interest when you try retelling it a few times. Or you might find that part of a story from one person complements stories from other participants.

Sometimes, these stories illustrate a single usability problem or a single user experience goal, giving you more specific data to work with. Sometimes, several pieces of stories start to collect into something richer than you would get simply by tying analysis points into a single narrative. The story can let you pull it together in a way that helps you focus on the bigger problem, even as you weave in some of the specific examples of how that problem affects users.

Telling stories is a natural activity, an easy way to sort through what you have learned. If you work with other people on user research or usability testing, you have probably done it without thinking, “I’m telling a story.” You just share bits and pieces that seem particularly memorable and juicy to you.

So far, we have mostly talked about stories that come directly from participants in user research or from your own observations. As we mentioned in Chapter 6, there is another source of user research, though you may have to dig a little deeper to find the stories in it: user information from search logs, Web logs, or other collected data about user behavior. These sources can give you details to use in your stories, such as the most frequent (or infrequent) types of searches, how long someone reading intently might stay on a page in your site, paths through the site, or even nonobvious connections between parts of a site.

This analysis tells us a lot about how people connect one activity to another, and how important having good, useful content is for attracting people to your site. Analysis insights like these can be the start of a story that illustrates why some pages are so attractive. These stories could be incorporated into a persona or combined with other user research to make the analysis memorable.

You can also use sources of information like technical support logs or questions in an online knowledge base to find raw material for “points-of-pain” stories. Do the problems users report match up to the problems you see in usability tests or the needs you hear about in other user research?

When you can triangulate between different data sources—draw the same conclusions by looking at the user experience through several different lenses—you are almost always on the right track.

If you create personas, they are a natural place to use stories. The stories you write for your personas let you transform facts into situations that bring static personas to life, giving them context and motivation.

The stories you tell about personas are a natural way of understanding people and events. Let’s look at three ways to describe a group of people:

Aged 30–45

Well educated: most have attended

college or have a college degree

45% married with children

Over half use the Web 3–5 times a week

65% use search engines

This profile is not very specific. It looks very precise with its percentages and statistics. But it does little to bring these statistics to life. Add some specific details: pick an actual age, not just a range. Then add some of the story fragments you have collected. These are things participants told us during a pre-test usability interview when we asked for examples of reasons they had used the Web recently:

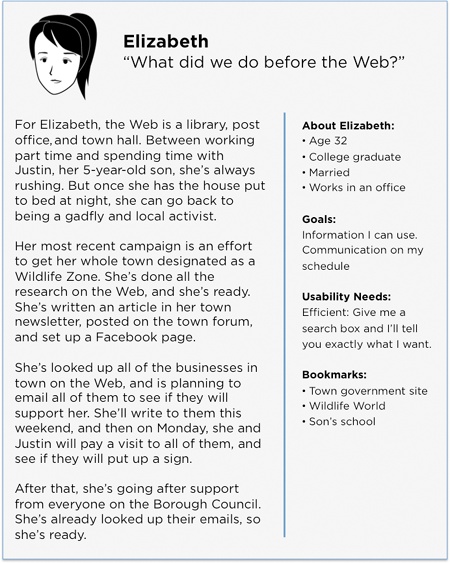

Elizabeth, 35 years old

Married to Joe, has a 5-year-old son, Mike

Attended State College and manages her class news on the alumni site

Uses Google as her home page and reads CNN online

Used the Web to find the name of a local official and how to contact that person

Now you have a person with some real activities. You can now develop those activities into stories (see Figure 7-2). The demographic details and other data are still there, but they provide a background for the richer description of the experience.

If you already have personas, you can connect your stories to them. This can have a number of advantages:

Stories add more richness (and underlying data) to the personas, making them more useful and helping keep them fresh and updated.

Using the personas as the cast of characters lets you explore internal conflicts, attitudes, or choices the personas make under pressure.

If you are working with personas that are little more than named categories, stories can help you understand the concepts behind the categories better.

Stories inspire more stories, so combining stories with personas inspires collaborators, stakeholders, and other team members to inject more life into the design project.

Stories breathe life into implicit cultural context of personas—like “35-year-old married, college graduate office worker”—which helps the audience identify better with the characters.

Sometimes, stories can even expose gaps in your user analysis. If a story doesn’t seem to “fit” well with any of the personas, and you are sure that the story illustrates an important analysis point, you need to stop and figure out what’s happening. You may be missing a persona, or you may find that there are some things you don’t know about your personas. Either way, the stories can help bring out those gaps before you design a product without considering them.

Including user research data in stories provides a powerful new way to communicate your work. Personas can combine stories from people with similar perspectives. Connecting different user experience techniques strengthens all of them, as each connection between them validates the conclusion, and adds to your ability to triangulate on user experience needs.

Your goal in analysis activities is to find juicy story fragments that you can develop into stories. When you start from a quote, anecdote, or image, add it to other fragments, and then distill it down into a narrative, you have a story that can explain “what’s going on here” in a clear way.

Selecting stories puts your “story thinking” to work, identifying stories that support other analysis. A useful set of stories makes sense of scattered pieces of information by doing the following:

Illustrating points you want to emphasize from the user analysis.

Bringing out details that are hard to communicate in any other way.

Connecting with other sources of information.

Resonating, not just by ringing true, but also because they are so natural and convincing that they spark action, like a discussion or a design change.