Merchandising, Video Games, Hotels, Pay-Per-View and Transactional VOD Roots, Airlines, and Other Markets

|

More content from this chapter is available at www.focalpress.com/9780240824239 |

This chapter combines a bit of a hodgepodge of revenue streams, but that is because an intellectual property asset, by its divisible and malleable nature, lends itself to being exploited via endless permutations, associated with a dizzying array of physical products, and distributed by any platform capable of attracting eyeballs. Given this open-ended sandbox to bring in additional dollars, in exceptional cases revenues from “ancillaries” can become the proverbial tail wagging the dog, generating more money than the property in its original incarnation. Merchandising, a category that could mean a thousand different products (ranging from toys, to games, to apparel), is what one tends to associate with ancillary revenue. I will accordingly devote the bulk of this chapter to merchandising (in the broad sense), and while it is beyond the scope of this book to delve too deeply into the games business, I will both touch on games as they relate to film/TV ancillaries and also discuss elements of social gaming. The evolution of data analytics, which is ever being fine-tuned by the gaming world, will inevitably influence all media consumption metrics and related advertising tracking and pricing.

Notwithstanding the importance of merchandising in the film and television world, in the context of distribution, a series of ancillary streams have carved out additional niche windows for exploiting content. The most prominent of these include:

■ hotel/motel

■ pay-per-view

■ video-on-demand (VOD) (here focused on its roots, briefly touching on Internet VOD, as OTT services are generally discussed in Chapter 7)

■ airlines

■ non-theatrical.

I will only cover these markets in broad concept, in part to illustrate their relative relationship to the more important revenue drivers. What is interesting is how the landscape has changed: in my first edition, I included transactional video-on-demand within this section, but have now moved the discussion of transactional VOD to the video chapter (as VOD has, as predicted, become the new face of rental video), a discussion of SVOD to Chapter 6 (as subscription VOD has become akin to pay TV), and Internet VOD to Chapter 7 (as part of the description of streaming OTT services). In the new order, VOD is truly everywhere, and as discussed throughout the book the increasingly ubiquitous access to content in an on-demand manner is collapsing the value drivers in Ulin’s Rule and putting unrelenting stress on the historical window system.

Finally, a quick note about online revenues—it would be fair to add online generally into this mix of “ancillaries,” because many view online as just another additive revenue stream. However, I am treating online as a separate almost “super category,” focusing on how it is impacting mainstream and ancillary revenue windows alike. In summary, that is the challenge of convergence: Are revenues from downloading a TV show to an iPod or streaming content to a tablet ancillary revenues, or rather new kinds of digital exploitation changing the very character of traditional markets (electronic sell-through supplanting DVD retail, and streaming content challenging the nature of what is TV)?

Merchandising revenues can be so significant that this ancillary market actually becomes the primary revenue stream targeted. Many animated properties originate from toys or with the intent of generating toy sales, with the producer sometimes viewing the cartoon (and, in extreme cases, its telecast) as a marketing expense. The challenge is that mer chandising revenues can be even more fickle than the film business, with toy vendors wary of the high risks even when dealing with name properties.1 Basing toys on a movie runs a dual risk that the movie will work and then that the movie’s performance can be converted into retail success with products based on the movie and its characters.

And yet, when a merchandising program takes off, it can be extremely big—in select cases, even bigger than all other traditional media streams combined. I had the privilege of cross-promoting videos with Star Wars merchandise, the all-time leader in merchandising sales from a film property. Commenting on cumulative sales generated over 35 years since the debut of the original film, the Hollywood Reporter summarized: “Over the span of Star Wars’ lifetime, $20 billion and counting of licensed goods has been sold, this on top of the $4.4 billion in tickets and $3.8 billion in home entertainment products.”2

In the era of social networking and digital versions of content, transmedia has been ballyhooed as a new buzzword for extending stories into other media and platforms; in general, the term refers not to sequels and remakes, but rather the production of new stories and content via different platforms and media, which serve to expand the fabric and experience of the core content. Whether this is fundamentally different than the notion of migrating a property into a franchise that is larger than the sum of its parts is difficult to define. Those trying to frame transmedia exploitation may argue that the difference is in planning: independent tangents are enabled from the get-go in an effort to create a broad, immersive experience where storylines are not linked, yet all tie together because of common grounding (which, in legal terms, reflects all the related properties being derivative works). No doubt, digital media helps enable these different threads. I would argue, though, that big enough franchises spawn an end result akin to transmedia storytelling, whether the end result is designed or simply evolves from opportunities to monetize different elements.

Star Wars, again, provides a good example. The following are some of the key tentacles of brand extension:

■ Toys: Toys such as action figures and lightsabers have been a staple consumer retail product for decades, defining the franchise as an evergreen.

■ Books: Searching the Web, one can find more than 100 different books (excluding graphic novels and comics) expanding upon the Star Wars universe, ranging in age demographics (e.g., young adult) and segmented by timeline (before or after X period of “history” in the saga). Additionally, the books include longtime relationships with leading brands such as Random House and Scholastic, several New York Times bestsellers, and estimates of more than 160 million copies of books in print.3

■ Video games: LucasArts was among the top independent games publishers for almost 20 years, with Star Wars games both tying into and expanding the Star Wars universe. (Note: LucasArts was closed in 2013 post Disney’s acquisition of Lucasfilm.) Lego alone has sold more than 15 million units of the Lego Star Wars video game, and the MMO Star Wars: The Old Republic (developed in collaboration between LucasArts and Electronic Arts’ BioWare), launched during the 2011 holidays, sold more than 2 million copies in its first two months, and according to the Hollywood Reporter about 1.5 million people were paying an average subscription of $15 per month during Q1 2012.4

■ Theme park rides: Star Tours, a staple flight simulator ride at Disney theme parks globally, debuted in 1987, and was then revamped in 2011.

■ Education: There have been multiple Star Wars learning products over the span of the franchise, including in the last few years a range of interactive educational games from leading children’s educational software company LeapFrog.

■ Television: The franchise has led to a series of documentaries, ranging from behind-the-scenes productions to Discovery Channel’s The Science of Star Wars. Additionally, the hit animated series The Clone Wars was among Cartoon Network’s top shows since its debut in 2008, averaging 2.2 million daily viewers, and has ranked as the top show for the boys 2–14 demographic.5

Arguably, books, video games, and television series taking characters and themes in different and new directions, in different media, often set in different time periods, enabling different and often immersive experiences yet all grounded in common iconography, is a form of transmedia storytelling. What is new today, however, when people often refer to transmedia, is the launching of a “franchise” with different elements from conception, enabling viral growth, which helps define and build a franchise. The formal definition of transmedia, or whether the tail wags the dog (or vice versa), though, is less important than the ability of intellectual property to be molded into different forms, formats, product, and media, which all can be independently monetized.

As Risky and Lucrative as the Film Business

What Properties Can Spawn Successful Merchandising Programs?

Most successful film- or TV-based merchandising programs are built around either franchise properties or properties targeted at the kids/family demographic such as animated features. To the extent that a property crosses over to both categories, namely franchises and kids, then the potential is that much greater. This is why films based on comic books have become so hot, and why brands such as Marvel have seen a resurgence. Even with this type of triangulation, nothing is a sure thing. Batman has been a success story, and more recently Spider-Man has hit its stride, but product based on Superman has struggled by comparison.

Star Wars has been the industry’s leading and enduring success story, somehow managing to strike a continuing chord with multigenerational fans and collectors. It is a legendary industry story how Lucasfilm was caught by surprise by the product demand back in the 1970s following the launch of the original film. Demand was so high that toy company Kenner shipped empty boxes with vouchers for product that would be shipped later. This story is instructive to illustrate (again) the similarity of vicissitudes to the film business; namely, the market is hit-driven and no one can fully predict what will catch on and when. Accordingly, the business tends to segment into two major categories: established properties, where the merchandise becomes part of a larger franchise management program, and newly released properties that launch with the hype of presumed success (e.g., a new Pixar film).

It then becomes the challenge of major product providers, such as toy companies, to place large upfront bets. The two largest U.S. toy companies, Mattel and Hasbro, are heavily courted by every studio and network, because having a major toy program in place not only validates the expectations for an upcoming release, but also provides cross-promotion via the brand marketing of the toy company. It is like joining a craps table, but now there are more people betting on the roll, with the energy and expectations feeding on each other; moreover, the drama is heightened by the fact that everyone gets only one roll (the film’s opening box office, or a TV series initial airings).

The Difference with TV

In many ways, merchandising driven off of TV is a much better business. This is because, with a continuing story, it is possible to hold back and see how a property is performing before ramping up too far. It is not unusual to wait for the second season of a series before launching major product; the time delay allows programs to be built around what the merchandisers now know is a hit. Moreover, with TV there is the ability to keep the property in front of its consumers week after week. The combination of a more calculated risk and a longer tail should produce a healthier ROI, a fact further buttressed because TV production costs should be lower than film costs.

Among the great success stories in this space is Power Rangers, a series/franchise that became so strong that it (together with thousands of hours of other animated content controlled by Saban Entertainment) allowed producer Haim Saban to launch and co-own Fox Kids with NewsCorp; Saban then netted a huge personal payoff (in the billions) when he sold the kids cable network to Disney (which then rebranded the network ABC Family).6 (See Chapter 7 for a discussion of how these profits were leveraged to make billions more with the purchase and sale of one of Germany’s leading commercial TV networks.)

Another prime example over the last 10–20 years has been an explosion of anime-based properties, including Pokémon, Yu-Gi-Oh!, and Dragon Ball Z, hitting U.S. television (properties that are, in turn, often derivative of manga magazines and graphic novels). Nintendo’s Pokémon turned into a phenomenon, becoming such a figure of pop culture that it appeared on the cover of Time magazine and the New Yorker, and a gigantic Pikachu balloon floated through the Macy’s Thanksgiving Parade.7 As an aside, I remember meeting the woman in Tokyo who created the signature yellow pocket monster character Pikachu, and autographs were so in demand that she regularly kept stickers with her to sign. In terms of numbers, Pokémon sales figures were daunting: from over 1,000 licensed products, it is estimated that global Pokémon merchandise sales exceeded $5 billion. And these numbers are from legitimate licenses—in 1999, Nintendo of America, the licensing agent for Pokémon, asked a New York court to crack down on pirates, alleging they were losing $725 million per year from counterfeit goods.8

It is the hope of these types of returns that excites the executives at all channels focused on kids programming. At Nickelodeon, SpongeBob SquarePants sustained a successful merchandising program for years. Disney uses its Disney Channel airtime to keep key characters fresh, such as with a CG-animated Mickey Mouse; moreover, it is also able to cross-promote items through its theme parks, networks, videos, etc., thus creating purchasing demand among each new generation of toddlers. Disney has also been able to expand its success into the teen demographic, as evidenced by its Disney Channel special High School Musical. This TV musical and its sequels (e.g., High School Musical 2), per Variety, “have sold nearly 15 million CDs, 50 million books, 4.8 million video games, and spawned stage shows, concerts, and an ice tour.” In terms of financial return, at the height of the High School Musical frenzy (2009), Disney targeted $2.7 billion from High School Musical and Hannah Montana products.9

In contrast, name a successful TV or film merchandising program not aimed at kids. There are a few, such as around The Simpsons and South Park, but outside of these edgy shows where the merchandising leverages the cult appeal of the show, there are hardly any examples. Dramas, police shows, action movies, romantic comedies, sitcoms, and even niche genres such as horror do not lend themselves to converting property interest to product purchases. Why? Arguably, it is all about time, focus, and independence. As people grow older and are more independent with their choices, with more influences competing for their attention, marketing messages are diluted, and the desire to affiliate with a character or item becomes less compelling. Simply, think of a graph, where the Y axis is range of choice and influences, and the X axis is age. The older you get, the more choices and the more exposure. In contrast, children watch hours of certain TV shows each week (if not each day), and a particular property is more integral to their lives.

Chicken and Egg: When Merchandise Drives TV

As outlined in Chapter 6, on occasion producers will pay for airspace and take on the risk of selling the commercial inventory to guarantee a broadcast slot. This risk tends to be limited to instances where there are strong ancillary revenues, such as built-in merchandising from an established brand, where the P&L is not simply based on advertising sales. A prime example several years ago was 4Kids Entertainment’s deal with Fox (4Kids holding TV merchandising and broadcast rights to Pokémon and other hit anime titles).

According to 4Kids Entertainment’s annual report, “The Company, through a multi-year agreement with Fox, leases Fox’s four hour Saturday morning children’s programming block. The agreement, which commenced in September 2002, requires the Company to pay annual fees of $25,312 through 2006.”10 The annual report continued:

The Company, through a multi-year agreement with Fox, leases Fox’s Saturday morning programming block from 8 a.m. to 12 p.m. eastern/pacific time (7 a.m. to 11 a.m. central time). In January 2005, the Company changed the name of the Saturday morning programming block from Fox Box to 4Kids TV. The Company provides substantially all programming content to be broadcast on 4Kids TV. 4Kids Ad Sales, Inc., a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Company, retains all of the revenue from its sale of network advertising time for the four-hour time period.11

Fox secured over $100 million over four years without any risk, presumably on the assessment that it could not sell $25 million of advertising per year in this space or otherwise net better than this amount after programming costs. The network’s bet seemed to pay off based on the 4Kids report, which lists advertising media and broadcast revenues for 2002, 2003, and 2005, respectively, as $11.2 million, $22.54 million, and $24.1 million. In addition to running a deficit on the airtime, 4Kids had programming costs to amortize. And yet, as the report further noted, the company’s belief that TV exposure would drive other revenues tied to the already established franchise justified the risk: “The ability of the Company to further develop its merchandising, home video, and music publishing revenue streams were significant components of its evaluation process which resulted in the decision to lease the 4Kids TV Saturday morning programming block.”12

In the context of leveraging well-known brands with strong merchandising lines, the 4Kids Entertainment strategy of broadcasting new (and inexpensive-to-produce) series on network to drive awareness for ancillary revenue streams was a bold play. However, absent this context the notion of paying for production, receiving no license fee (and, in fact, having a negative license fee given the lower ad revenues versus the cost of the airtime), and betting the entire economics on ancillary revenues may carry worse odds than gambling.

Most Extreme Example: Toys Programming a Whole Network

The natural extension of the 4Kids experiment with Fox and programming a block of TV content is to take over and program an entire channel. With exposure difficult and a few key players controlling the network flow, both independents and toy companies recently changed strategy and have opted to become both the programmer and owner.

In 2009, Hasbro bought 50 percent of Discovery Kids to launch The Hub, a new children’s network with a reach of approximately 60 million subscribers. While Discovery continues to manage advertising sales, programming is the responsibility of Hasbro—meaning that a toy company is leveraging a major cable network to promote its brands (e.g. Transformers), with animated series such as Transformers Rescue Bots and Transformers Prime.

Another example of a children’s production company launching a network is PBS Kids Sprout. The channel originally launched in 2005 as a partnership among Comcast, HIT Entertainment, PBS, and Sesame Workshop. HIT Entertainment, launched originally as the overseas television arm of the Jim Henson Company (Henson International Television), had gone public and bought the iconic U.K. brand Thomas the Tank Engine. The new network enabled HIT to have a direct television outlet via which to air series and cross-promote its brands. (Note: In 2011, Mattel bought HIT Entertainment, bringing not only Thomas the Tank Engine, but global brands Barney and Bob the Builder under its umbrulla; however, HIT’s ownership interest in Sprout was not part of the transaction. This makes sense given the educational focus and mission of PBS and Sesame Workshop, which would arguably have been in direct conflict with having one of the two largest toy companies (Mattel) as a major owner.)

In A World of Apps, Do Toy Company–Network Partnerships Make Sense?

Given the growth of the app space, and the rise of brands such as Angry Birds into global franchises, it will be interesting to watch whether the appetite for toy companies to invest in linear television programming continues. Rovio, the Finnish developer of Angry Birds, riding the crest of over 500 million downloads (mobile and online) reportedly turned down a $2.5 billion bid from social games pioneer Zynga at the end of 2011.13 This phenomenal growth in under two years is an example of digital power—the downloads combine use across cell phones, tablets, Web browsers, and computers, and according to Rovio users engagement was a staggering combined playtime of 200,000 years and 400 billion in-game bird launches.14 Because apps and TV measure metrics so differently, it is difficult, if not impossible, to compare like-for-like value; nevertheless, if one were to harmonize a metric of user engagement, no doubt Angry Birds would come out near the top, if not a clear leader.

The number of toys and other merchandise that Angry Birds spawned would be the envy of any toy company. Rovio targeted sales of 20 million Angry Birds toys at Christmas 2011, and in an interview with Forbes, GM North America Andrew Stalbow noted the following statistics in highlighting the company’s efforts on bridging the digital and physical world in 2012: “We’re selling over 1 million plush toys every month. We have apparel in stores like Walmart and JC Penney. We have three new books in stores now—the cookbook and two dootle books. We had the number one ‘most searched for’ Halloween costume.”15

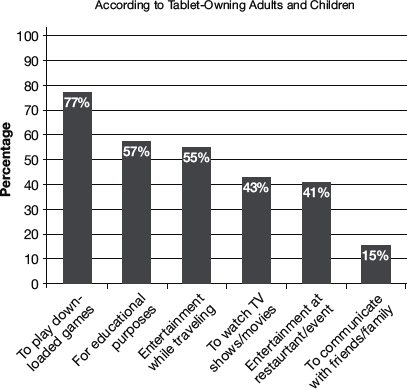

Figure 8.1 How do Children Use Tablets? Reproduced by permission of Nielsen

Reproduced by permission of Nielsen

With the power of the app-driving-merchandise model proven by Rovio, a toy company looking to market its brands would then need to ask whether this is a fluke, or whether there is a broader phenomenon building in terms of digital devices grabbing the attention of its core consumers (i.e., kids). A study by Nielsen in Q4 2011 implies yes: of households with tablets, 77 percent of children under 12 used the tablets to download games, compared to 43 percent that used them to watch TV (Figure 8.1).

These statistics suggest something even more powerful—clever marketing and integration that could take advantage of a tablet’s combined power for downloads and watching TV/video suggests that a brand leveraging the power of new digital devices can drive penetration, consumption, and brand awareness on an unprecedented scale. Moreover, because the cost of developing apps is a fraction of producing linear television (suite of top apps in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, versus the cost of a season of animated TV programming in the millions of dollars), access is not controlled by the filter of programming executives (apps can be democratically launched across multiple platforms). Further, since marketing and advertising costs for apps are lower (though costs are increasing, costs are still significantly lower, as well as capable of being more finely targeted direct-to-consumer rather than direct-to-demographic), toy companies with investments merely focused on controlling a slice of airtime are likely to find themselves playing catchup with those that can optimize this new ecosystem.

E-Commerce Plus Web-Based and Social Media Extensions

Although discussed in Chapter 9 regarding marketing, it is important to highlight in the context of merchandising the role the Internet plays. Virtually all films and major TV shows have dedicated websites, and within these websites users can often directly link to e-commerce applications to buy related merchandise. When I took over managing www.starwars.com, I was pleasantly surprised to learn (and I guess I really should not have been surprised) that one of the thriving parts of www.starwars.com was the Star Wars shop. This store, like many other Internet boutiques, was able to include within its product mix special online exclusives; more targeted marketing, and the ability to offer limited quantities, will sometimes allow a diverse SKU of unique items that may not be viable in the hyper-competitive environment of retail shelf space.

Since my first edition, the concept of dedicated “sites” has expanded such that a website is now not enough; all key brands also have parallel social networking sites, such as a Facebook page. Social networking sites can help cross-promote and link merchandising elements, even if the store may be embedded elsewhere. Additionally, video/TV properties lend themselves particularly well to apps, and a major franchise is apt to drive consumption via a combination of apps, social networking, and websites, all leveraging each other and capturing user data across the spectrum. As discussed in Chapter 9, the challenge today is to create efficient metrics and dashboards to enable brand managers to optimize engagement around key branding events (e.g., launches), capture user data to efficiently update and market to “fans” between events, and push out messaging that is configured for personalized storage and virally spread when touched (be that consumed, viewed, recommended, etc.). The critical element to this new paradigm is the personalized level of communication; in terms of merchandising, it is therefore not surprising that the trend has been pushed down to the personal level as well.

The tangible manifestation of everything being pushed down to the individual level is customization of merchandise, with e-commerce platforms able to create “print-on-demand” solutions for a range of product. Café Press and Zazzle are among the biggest names, with companies enabling fans of shows to customize a range of items, from apparel, to housewares (e.g., coffee mugs), to cell-phone covers. Images and even buzz slogans from characters can be customized with your name, or in a pattern chosen by the consumer. Because (in theory) this business does not require inventory, but rather companies can print or manufacture product on a 1:1 basis based on the particular customer order, a material business can be created with relatively small staff. All order manufacturing, invoicing, marketing, etc. is done via the website, fulfilment can be performed using third-party delivery services (leveraging the Amazon model), and, depending on the product, it is even possible to outsource the actual production. Not surprisingly, there are various companies, such as MashOn, leveraging this new on-demand model to deliver customized products tied to movies, TV series, and even games.

In addition to enabling e-commerce merchandise applications (both for digital and physical product, including items available only via the Web), the Web has enabled the phenomenon of secondary markets. Everyone is familiar with stories of the value of old comic collections, and eBay has enabled a vibrant marketplace for collectors—in essence, giving an entire new life to the collectibles market. While eBay is obviously a broader phenomenon, it is a boon to the world of merchandise.

A licensing program is based around trademarks affiliated with a movie or TV show, and creates a variety of product categories leveraging the brand and key characters. The categories are as diverse as one can imagine, and the following is just a sample list:

■ toys and games (including now app-based and social games)

■ apparel and accessories (including backpacks)

■ publishing (e.g., books, magazines, activity books)

■ interactive (e.g., computer games, platform games)

■ mobile (ringtones, wallpaper, etc.)

■ domestics (e.g., sheets, towels, bath and bath accessories)

■ housewares

■ social expression (including greeting cards, stationery, etc.)

■ sporting goods

■ food (including salty snacks, cereals, packaged goods, frozen, etc.)

■ gifts and collectibles.

Top brands can have literally hundreds of licensed properties, and the range of the program and how fine the categories are segmented depends on the property and philosophy of the licensor. The digital and online world is further expanding the possibilities, as movie sounds and music have been adapted for popular ringtones, and it is now possible to license avatars and digital accessories in a variety of environments.

Product merchandising, however, is an area where more is not always better, and the success of a program will depend on the commitment of the licensees and the licensor’s ability to exercise controls both with licensees and with retail to ensure quality and a level playing field for product.

Retail Buy-In and Support

A licensing program does not stop with concluding licensing deals, because a successful campaign will also have the licensor working with key retail accounts and licensees to ensure placement and coordination at retail outlets, which today also includes e-tailers. Amazon has a form of retail space and with home page placement, e-mail blasts, alerts, targeted marketing, and cross promotions, a campaign can materially influence the success of tied merchandising. A challenge with online, though, is that it can adjust more quickly and more democratically to index promotions to search and purchase metrics; thus, a successful product may build on its traffic (successful sales lead to a virtuous cycle of more frequent or better-placed search results and cross references), but it is harder to influence an underperforming product as the results, not promise of results, will dictate exposure (i.e., if underperforming, a producer will argue that warrants greater promotion since the title is not being found as expected, and yet the search results and indexing for promotion will actually be reduced since they are often linked to actual results, creating a downward spiral of reduced promotion; the nature of the online metrics linking to actual results tends therefore to accentuate the extremes, adding promotion to what is already successful, and perhaps too early bailing on a title not yet performing). As for large physical retailers such as Walmart, Target, and Toys “R” Us, these key accounts will stock a variety of products related to the brand, but will be dealing with separate and unrelated licensees, with each pushing its product at the level of the department buyer. To the extent an event (e.g., movie launch) or brand warrants it, special standees and sections can be created, pulling product from multiple departments, creating incremental retail placement, and highlighting the brand; moreover, if the retailer buys in and believes aggregating product will drive traffic, then the retailer is also more likely to promote and advertise the selection, either in circulars and/or with hard media using co-op advertising funds. When the last Star Wars movie was released, for example, the merchandising program was robust enough that Walmart even participated in special “tent” events at select locations: What could be better than not having to leave the parking lot to fight with a lightsaber?

Any successful licensing program will therefore focus on retail-specific programs. You know you have stepped into a licensing meeting when an executive is talking planograms and live on-shelf dates. Another reason retail engagement is so critical is that the very nature of product merchandising speaks franchises, and if there is oversupply of product or too many licensees, such that the retailers get hurt (as opposed to the product licensees), then a campaign is not only unsuccessful, but the future is undermined. Some will take a “take the money and run” approach, focusing on guarantees, but a successfully managed campaign will spend as much time working retail engagement, placement, and metrics as the deals for the products themselves.

Licensing has a longer development/planning cycle than any of the traditional media categories (e.g., theatrical, video, and TV distribution), which often puts crazy pressure on divisions to lock in plans before the details of a project are even worked out. If cutting a trailer for a film is difficult because the movie is not yet done, then creating product for that movie takes the challenge one step further because decisions often need to be locked before the filming even starts.

Timing

Lead times of two years are not unusual, and anything short of 18 months may make developing product and getting it on-shelf in time impossible. This is simply the nature of product development—the entire supply side, from designs, to materials, to molds, etc., takes time. Virtually everything is outsourced for manufacturing, which means location and subcontractor decisions are involved, plus product samples need to be made and approved. (Note: Product placements (which can sometimes be confused with merchandising), such as a special car being featured in a film, similarly need long lead times, as the integration has to occur before filming. See Chapter 9 for a discussion of product placements.)

Style Guides and Quality Approval

Before any product is made, the licensor will create a detailed style guide. This guide will include the logos and typefaces to be used (including a variety for different types of packaging and sizing), approved artwork for characters, including in different poses and turnarounds (e.g., flat and dimensional), approved trademark and copyright notices, approved color palates, approved phrases, approved peripherals (such as weapons or vehicles from the property), approved size charts (relative scale of one character to another), etc. KidScreen magazine, describing how a style guide can differentiate a pitch and is at the heart of any consumer product program, referred to style guides as “doing overtime as a calling card, a presentation piece, a licensee manual and a brand road map all at once. So getting the right style guide is crucial to scoring a [merchandising] hit.” It then continued to detail the elements of a guide: “Most guides start off with a general description of the film or TV show and then get into the nitty-gritty graphic components, including icons, logos, color guides (breaking out main, secondary, and accent palettes), character and background art, prints, borders, patterns, phrases and text that can be used, fonts and sample product applications.”16

The goal of the style guide is to create brand consistency. If over 100 products are made in varying media and mediums, the licensor needs to provide a blueprint around which specific items are then designed. In the case of Barbie, which has approximately 1,000 licensees working across 45 product categories, there is a template to rein in too-divergent elements, but Mattel claims that while “you do need a few rules, because that’s how a brand becomes clear and cohesive,” they strive to work with licensees throughout the process and avoid steering the process through too narrow a creative tunnel.17 The style guide then provides a working anchor for quality control, as sample designs and product must stay within the parameters outlined. To the extent the product is consistent, then the licensor’s review for quality approval is infinitely easier.

This is one of those areas where I touch upon it in a paragraph or two, but the execution of the style guide and approval over designs and sample product are the lifeblood of the merchandising campaign. Failure to timely approve items or to properly inspect quality are the surest way to doom a program, and cannot be taken for granted. This becomes an economic consideration, because once deals are signed, there is the temptation to assume “licensees know what they’re doing” and relax. In fact, it is tempting to cut budgets around personnel to review product, especially as the numbers and categories grow. Almost all merchandising managers will testify that they have rarely seen cutting corners pay off, because there is nothing more competitive than the retail shelf, and consumers are always savvier than anticipated. This is why companies will invest significant funds up front in the creation of a style guide (most aspects of which can apply to online/digital representations as well), with the bill ranging from tens of thousands to well over one hundred thousand dollars.

I have waited until this point to describe key elements of licensing deals to punctuate the point made earlier that while signing up licensees is obviously critical, if a licensor puts full stock in that element at the expense of developing sophisticated plans for approvals, style guides, and retail management, then, at best, license deals will not be optimized and, at worst, undermined.

Licensed Products and Property

“Licensed product” is exactly as it sounds: the specific products being authorized, such as action figures, T-shirts, key chains, digital avatars and accessories, or wallpapers. The “Licensed property,” in contrast, refers to the underlying rights (e.g., trademarks) upon which the products may be based.

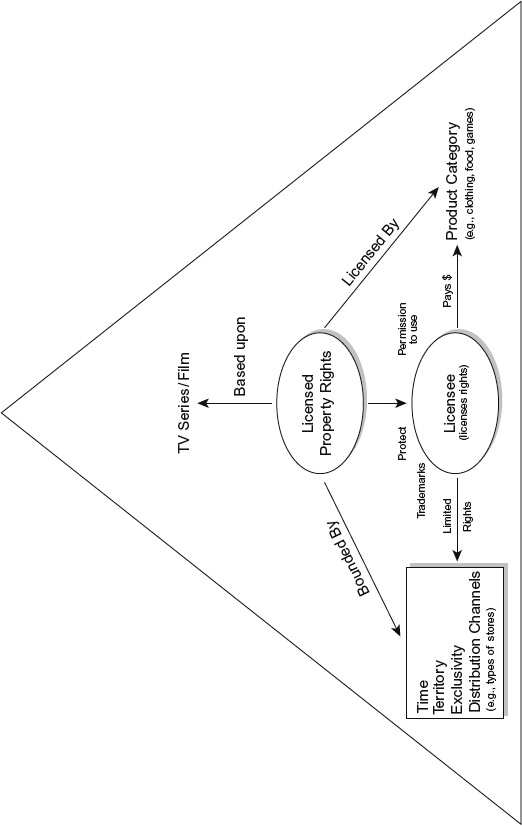

Licensed Rights—Exclusive versus Nonexclusive Rights to Licensed Properties

The license agreement will make it clear (hopefully) whether the licensor conveys either exclusive or nonexclusive rights to use the licensed property in connection with a defined category of licensed products (and to add further legal boundaries, of course during a limited term, and restricted to the defined territory). Because the license rights ultimately derive from the ability to use the licensor’s trademarks with products based on the underlying property, to the extent the licensor is allowing multiple products, then conceptually the license is nonexclusive; however, most licenses carve out a measure of category exclusivity, such as the exclusive right to make watches or trading cards. It is this niche level of exclusivity (whether a de facto practice adhered to on a relationship basis, or expressly granted) that allows franchises to spawn hundreds of licensed goods and obtain minimum guarantees against narrowly defined category exclusives.

Although most film-based licenses tend to be category-exclusive, one can also find general market examples of nonexclusive product licenses. A prominent example is found in sports, where individual teams may permit a number of manufacturers to make a product such as multiple companies creating apparel using team logos (in which case, one shirt may bear trademarks of Nike and Team X, and another shirt Team X plus Y).

Not only can the license be bounded by time, territory, product category, and exclusivity, but even by types of distribution outlets (e.g., novelty stores, grocery stores). This is somewhat akin to the video market, which is differentiated into retail categories (such as rental and sell-through), though ultimately much more complex because the segmentation adds the complexity of the character of the outlets rather than resting on the clearer dividing line of price and type of transaction (see Figure 8.2).

Economics: Minimum Guarantees/Advances

Minimum guarantees are important at two levels: first and foremost, they ensure the licensor a revenue floor, and second, they create incentives for the licensee to push the product to meet and hopefully exceed the guarantee. Licensing deals rarely stray from the concept of an advance against royalties, with these two items as the focal point of negotiations. This is not to trivialize other elements of the deal, or argue that when and how advances and royalties are paid is not critical, but it is important to recognize that at the heart of any licensing deal are relatively simple and direct economic terms. Unlike net profits from a film (see Chapter 10), Hollywood has not evolved arcane accounting standards around merchandising: at its guts are how many units are being sold, what the royalties are (and how they are calculated), and what amount, if any, the licensee will front against the royalties.

One wrinkle that can arise around minimum guarantees is that a licensor may want minimum royalty payments over defined periods such as on an annual basis. These thresholds are designed to ensure that licensees are continuing to market and push products; if certain sales targets are not met, this could trigger the right to terminate the license (or, conversely, extend the license if they are met).

Licensors are dealing with brands that have inherent awareness and goodwill (here, someone willing to pay money pursuant to a trademark license to associate a consumer product), and the ability to guarantee continued levels of sales and exposure can be as critical to brand management as the associated revenues. These types of licensors will not “take the money and run,” but rather take the money and make the licensees keep running. This is fundamentally different from deals based on straight license fees (e.g., TV, assuming no ratings bonuses), in which initial marketing commitments may be established, but thereafter the broadcaster has flexibility. In the context of TV, broadcasters typically have the obligation to pay the license fee, but then assuming the fee is paid they do not actually have to broadcast the property. Merchandising deal structures are more like video, where product sales are dependent on shelf space, retail execution, and thousands of points of purchase; similarly, both are consumer products, upsides are generally tied to volume, and with a licensor’s participation set as a per-product royalty.

Figure 8.2 Licensing: Product Merchandising Ecosystem

Royalties

Royalty calculations are generally straightforward, and are expressed as a percentage of sales. The challenge is in defining sales, and then specifying what, if any, adjustments or deductions are permitted. First, in terms of sales, the product can be sold at multiple levels, such as wholesale and then retail (with further wrinkles if a product may be purchased from an overseas manufacturing facility where the pricing is pre-shipment and wholesale markup). Much like the context for video sales/royalties, the only pot of money a licensor taps into is at the wholesale level. A licensee makes its product and sells it to a customer (e.g., a retailer), and any corresponding royalty needs to be based on the gross revenue derived at this level. This is nearly an exact parallel to royalties/revenue that are accounted for at the wholesale price with respect to video. The one wrinkle here regards digital goods, for a digital asset—such as a character upgrade or weapon/accessory in a game—does not need to be manufactured, and accordingly royalties will be set off the consumer price.

Once the “gross” pot is defined from which the royalty is calculated, the next concern is defining whether there are any adjustments to this gross; a concept that is sometimes made confusing by defining this gross amount as “net sales.” There are multiple elements that may come into play to reduce the base from which royalties are calculated (e.g., Can a licensee apply trade and other discounts, such as cash discounts? Can a licensee have an allowance for free or promotion goods?). While it is standard to allow some deductions, as well as apply a cap on total deductions, much of the risk ends up transferred to the licensee. As noted earlier, the concepts of net and gross track common sense expectations and generally do not devolve into arcane accounting schemes.

Finally, it is worth touching on setting royalty rates. Unlike the video context, where there is a relatively clear economic logic to splits (see Chapter 5 for a discussion of setting royalties to approximate cost of the top splits), royalty rates in the merchandising areas tend to be set on straightforward percentages without the parties trying to match a cost of the top split or other structure (likely because of the low cost of goods, the production of which has been outsourced to Asia/lower-cost production centers decades before this became trendy in other businesses, and the opportunity costs of having to deal with this calculation on hundreds of different products). Of course, the notion of splits underlies the setting of any royalty, but the point is that there is less of a conscious mechanism here; rather, the percentages tend to be within customary bands per product category.

It is a trade secret what those bands are, but suffice it to note that certain product categories may be in the very low single digits, while others can be a multiple of this range and command double digits. The Los Angeles Times, quoting a toy analyst, noted regarding the range: “The studios license the rights to toy manufacturers and also receive royalties of 7 percent to 15 percent of the sales, said Chris Byrne, an independent toy analyst and contributing editor of Toy Wishes magazine.”18 The Hollywood Reporter, in its survey article prior to the annual New York Toy Fair (2008), pegged the numbers a bit higher; estimating for top properties that licensors usually receive an advance guarantee in the $1 million range, it references a group publisher from License Global magazine in citing that studio licensors receive a 10–15 percent royalty on wholesale (and that wholesale is roughly 50 percent of retail), and that for certain franchises such as Pixar’s Toy Story, the percentages can be even higher.19

A final element worth mentioning in the context of merchandising royalties is the impact of distribution fees, which tend to be much higher than those applied for non-ancillary streams. It is not uncommon for a merchandising agent/distributor to charge fees from 30–50 percent, the high percentage justified by the presumably tougher job of managing (and selling) multiple product SKUS, timelines, and quality control (see also “Role of Agents” below). Accordingly, the net to the licensor is impacted by comparatively low royalty rates (to an extent driven by thin margins) and very high off-the-top fees—a formula that means only a fraction of the wholesale revenues (and remember, this is a fraction of the often-quoted retail sales) ends up paid to the producer/owner of the TV show or film upon which the product is based.

Premiums are licensed product that are given away to consumers rather than sold. This may take the form of a figure included with a kids’ meal at a fast food restaurant chain, and the issue for the licensor is on what basis is it paid: the consumer has not paid anything for the item of merchandise, and yet the licensor needs to be compensated. Economically, there are two theoretical routes for compensation. The first would be to allocate a portion of the sale, treating the premium as a bundled good and attributing a percentage of the purchase price to the premium. This, however, is not feasible for a variety of reasons: (1) the retailer (e.g., restaurant) is not going to allocate away from its core product; (2) the product is temporary, in that the premiums are offered only during a short promotional window, which means that the same allocation would need to be offered for all product among competitors (e.g., Burger King is not going to give Warner Bros. a better deal in March for the product packed in a kids’ meal than they will give Universal the following month); and (3) there may be no wholesale price (as the retailer will sometimes directly commission and manufacture the item).

Given these complications, compensation, to the extent there is direct compensation at all and this is not viewed as marketing, may instead be based on the manufacturing price of the item. A royalty would then be calculated based on the production cost, which amounts to a nominal number per item. The licensor will agree to this small basis because the nature of premiums is promotional (and at some level it is only mutual leverage that keeps them from having to pay for this promotion), the products are very inexpensive (almost disposable), and, at essence, royalties on the product are an incremental upside and not the driver of the deal.

Licensing at an elemental level is about sales, and every company has to make economic decisions balancing the cost/benefit of an in-house licensing department versus outsourcing the function. Even with a large in-house staff, however, some elements will still be outsourced to ensure global coverage (there is simply not enough consistent throughput for most companies to have dedicated staff in all major markets worldwide).

Most companies will therefore utilize either a master agent or a network of agents, managing this sales staff via commission structures. The agent will be responsible for sourcing deals, helping negotiate contracts, monitoring quality and performance levels of the licenses, and in some cases even overseeing collections. The licensor then has the decision of what level of autonomy to authorize, and to what degree it will delegate management functions either up front (deal terms/selecting licensees) or during management and maintenance (e.g., product approvals). The degree of work will dictate whether the agent receives only a commission tied to royalties, or has an additional retainer/higher fees for performing overhead functions.

In addition to agents scouring the market to set up product licenses, the business is now so big that Hollywood agencies separately represent toy companies and individual properties to try to set up tie-in movie and TV deals (e.g., WME represented Hasbro to turn games such as Trivial Pursuit and Candy Land into film and TV products tapping its talent roster).20

Toys are the sweet spot of most merchandising programs, and a licensor leveraging a film property will usually first attempt to sign a master toy license. Such a toy license will cover a range of potential products, such as toy vehicles, action figures, and themed props (e.g., swords, guns, apparel). For perspective, it is important to understand the breadth of the market, not simply in overall licensing program terms, but also in terms of diversity of toy revenue. For example, while action figures are undoubtedly a key driver, creating stimulus for kids’ role-playing and buying ancillary accessories and props, action figures make up only a part of the puzzle. Action figure sales have hovered around the same percentage of the overall market in the last several years—$1.25 billion of the $22.6 billion overall toy market in 2006, and $1.3 billion of the $21.18 billion market in 2011 (both estimates by NPD group).21

In terms of how big merchandising tied to an individual film can be, it is possible to earn in the hundreds of millions of dollars. Business Week, in an article describing how Marvel and the whole industry underestimated the extent to which The Avengers (summer 2012) would be a hit, noted that Hasbro would make around $150 million in sales from Avengers product. While that may seem like a great success, in quoting an analyst from BMO Capital Markets, it noted: “Normally, a movie that makes more than $1 billion at the box office would produce $250 million to $300 million in toy sales …”22

Mega Deals: Star Wars and Spider-Man

The amount of money that can be made from toys can reach extraordinary heights, as evidenced by Hasbro’s success with Transformers and its deal with Lucasfilm for Star Wars merchandise (pre Disney’s acquisition of Lucasfilm). Discussing an extension of its initial $590 million agreement with Lucas Licensing (Lucasfilm’s merchandising arm), Hasbro advised that, in addition to a term extension, the new agreement lowered “the minimum payment guaranteed to the film producer George Lucas because of less-than-expected sales. The minimum payment was reduced by $85 million, to $505 million.”23

Another example is Marvel (also pre its acquisition by Disney), where Hasbro put up a $200 million-plus guarantee for toy and game rights across Marvel’s properties, including Spider-Man, Fantastic Four, and X-Men for five years; Spider-Man was clearly the driver in the deal, as the New York Times reported the “license guarantees Marvel $205 million in royalty and service fee payments, of which $70 million and $35 million would be payable on the theatrical release of Spider-Man 3 and Spider-Man 4, respectively.”24

These types of guarantees and deals are clearly high stakes. In the case of Hasbro and Star Wars, to some degree the toy manufacturer bet the company, as in addition to paying huge guarantees, Lucasfilm was granted $200 million in warrants for Hasbro common stock, which Hasbro had the right to repurchase.25

In recouping guarantees in this order of magnitude, one also has to keep in perspective that the dollars available are based on the wholesale amounts. As discussed previously, just like box office and film rentals, the relevant sums here to recoup advances are based on the net wholesale revenues, which extrapolate up to staggering sums needed at retail to break even. In analyzing the risks Hasbro was taking on its Marvel licensing deal covering Spider-Man sequels, one analyst that ultimately believed the deal would be profitable, despite its cost, was quoted by the Los Angeles Times as saying: “The company needs $1 billion in Marvel-related sales over the next five years to make a profit on the license …”26

Perhaps with this much at stake, it is not surprising that studios, and in particular Disney, have tried to leverage their consumer products infrastructure to optimize merchandising sales tied to key film properties. Disney, which in the last few years has bought both Marvel and Lucasfilm for the franchise value of their key brands (e.g., Iron Man, Star Wars), clearly looked to merchandising upsides as part of its rationale for the deals. When acquiring Lucasfilm, the Hollywood Reporter referred to Disney’s CFO Jay Rusulo’s statements in paraphrasing: “in 2012, Lucasfilm revenue from licensing and merchandising will be around $215 million, which is roughly equal to what Marvel was doing when they acquired that brand in 2009. Since then, Marvel has seen big increases in consumer product sales and Disney expects the same to happen with Star Wars.27

Rank |

Company |

2011 sales |

Brands |

1 |

Disney Consumer Brands |

37,500 |

Mickey Mouse, Disney Princesses, Disney Fairies, Toy Story, Cars, Marvel Brands (Note: Marvel, which in 2007 was #5 overall, in 2011 contributed $6 billion of Disney’s $37 billion-plus.) |

5 |

Warner Bros. Consumer Brands |

6,000 |

DC Comics superheroes, new characters for film and TV |

6 |

Nickelodeon and Viacom Consumer |

5,550 |

Dora, Diego, SpongeBob SquarePants, South Park, Neopets, miscellaneous TV Products properties |

14 |

DreamWorks Animation |

3,000 |

Miscellaneous animated properties/films |

15 |

Lucas Licensing (pre acquisition by Disney) |

3,000 |

Star Wars, Indiana Jones |

With this level of sales, it is not surprising that studios, networks, and producers controlling franchise rights are among the largest sellers of licensed merchandise, along with sports leagues and other major consumer brands (e.g., clothing, electronics, autos). License Global magazine, which performs an annual survey of the industry, listed several media companies in its top rankings (see Table 8.1).28

Coming Full Circle: Toys Spawn Films Spawn Toys

In the ultimate example of coming full circle, the Hasbro toy brand Transformers spawned a movie, with the movie then serving as the catalyst for a diversified product licensing program. The Los Angeles Times noted that Hasbro, confident of boosting its Transformers brand, had “signed deals with 230 licensees worldwide for T-shirts, bedding, cell phones and shoes.”29 This Transformers campaign turned into a huge success, with the initial film garnering more than $300 million at the U.S. box office (and more than $700 million worldwide) and increasing Hasbro’s sales of Transformers toys fivefold from $100 million to $500 million, proving synergy between merchandising and toys.30 The franchise has since gone on to include three sequels, with Transformers 4 set for summer 2014, and Transformers: Dark of the Moon itself grossing over $1 billion at the worldwide box office in 2011.

This Transformers synergy was so successful that the company aggressively moved to repeat this type of success. In 2009, Hasbro and Paramount partnered on G.I. Joe: The Rise of Cobra, which garnered more than $300 million at the global box office and led to a sequel, G.I. Joe: Retaliation. With its proof of concept, Hasbro struck a multi-picture deal with Universal to develop films related to its other key brands, including Monopoly, Candy Land, and Battleship.31 Despite significant media hype over this partnership, the companies parted ways at the beginning of 2012. Their biggest film project, Battleship, starring Liam Neeson, reputedly cost $209 million32 to make, but grossed only $65 million from the U.S. box office, debuting in May 2012 leading off the summer season.33 Hasbro and Universal continued to partner on Ouija, but on an entirely different investment scale, with the film originally in the $100 million range and then later reputedly targeted in a low budget range of $5 million for a 2013 release.34

The thirst for tie-ins and the perceived virtuous cycle of toys spawning films spawing toys, however, continues, as Sony quickly jumped in to work with Hasbro, partnering with Adam Sandler and his Happy Madison Productions to develop a movie based on the hit game Candy Land.35 Accordingly, if Candy Land comes to fruition, Hasbro will have launched major feature films based upon its toy lines with three different studios, generating global box office well over $1 billion, and making it one of the leading independent production companies in the world.

Toys and the Internet—Growing Crossover with Avatars and Virtual Worlds

One would think, conceptually, that toys, dolls, and stuffed animals would be one category somewhat isolated from the impact of the Web. This is not the case, as toy companies and studios are finding ways to cross over categories, creating new interactive elements to established franchises and growing entirely new brands and worlds.

Mattel, which previously took Barbie from a doll to TV movies and direct-to-videos, launched www.barbiegirls.com, where kids can play with avatars and unlock “VIP” content (by paying for them, or plugging in a Barbie MP3 player bought at retail that unlocks characters when connected). Rival toy company Hasbro built a virtual world to complement its Littlest Pet Shop, where each pet has a code in its collar that allows users to enter the site. Not to be outdone by the toy companies, Disney experimented with a couple of Web-related toy lines, including “Clickables,” based on Disney fairies, which enables kids to interact with a linked virtual world. Summarizing the trend at the 2008 annual toy conference, Toy Fair, the Hollywood Reporter noted: “The biggest trend industrywide at Toy Fair … is the increasing number of toys being sold that connect to Internet play and, with the inputting of special codes found on the toys, unlock virtual worlds.”36 And when there is new value, everyone starts to jump on the bandwagon: one of the original success stories, Webkinz, had a value in 2008 estimated by some in the $2 billion range. Their website is kid-friendly and simply states: “Webkinz pets are lovable plush pets that each come with a unique secret code. With it, you enter Webkinz World where you care for your virtual pet, answer trivia, earn KinzCash, and play the best kids games on the net!”37

As noted above in the context of Rovio’s Angry Birds, apps are becoming a leading outlet for creating virtual worlds and playing with avatars. This is apparent by looking at the paid app section of Apple’s iTunes store, where apps tied to leading kids brands are often among the top sellers. In fact, the Wall Street Journal noted how three of the top five apps in summer 2012, and in fact the top three slots at one point (including Temple Run: Brave, tied to the Pixar film Brave, and top app Where’s My Perry? linked to a character from Disney television cartoon Phineas and Ferb) were from Disney. The Wall Street Journal, focusing on the trend of kids playing apps on smartphones, noted: “Now, with kids spending more and more time playing games on their iPhones, big companies like Walt Disney Co…. are increasingly using apps as a distribution channel for their own brands while hunting for hits they can exploit in their broader operations.”38

Whether or not an avatar, used in a virtual world, on a mobile phone (e.g., tied to instant-messaging services), in a tablet app, or in social networking sites (where the lines are being blurred for kids, as in communities such as Club Penguin), is a type of virtual ragdoll is up for debate. What is clear is that toy companies and entertainment brands are striving to find ways to expand their characters and worlds into the virtual space. Moreover, once this transition is made, the entire merchandising food chain starts anew in the virtual world, with opportunities for e-commerce (pay to dress up your character or buy him or her accessories), linked games, apps, etc.

In my prior edition, I asked Howard Roffman, then president of Lucasfilm Licensing, who had overseen Star Wars-branded merchandise for over 20 years, what he thought about the online world’s impact and whether virtual merchandise would become as big as toys. He stated:

The online world is definitely beginning to impact the world of merchandise licensing, and that impact is rapidly evolving; we are just seeing the beginning today. Online retailers can offer higher-end collectibles that would be challenging to sell through traditional retail, such as the very large and expensive building sets that are offered exclusively through Lego’s online “Shop at Home” outlet. Online also offers opportunities for customization and targeting discrete market segments that would not be practical through brick-and-mortar outlets. While it is hard to imagine purely “virtual” goods such as avatars and ringtones becoming as large a market as traditional toys and many other popular mass-market categories, the day is clearly coming when content-driven items such as video games and DVDs will be consumed primarily via the Internet, all but eclipsing traditional retail.

Extending the Franchise: Video Games, Books, etc.

Video games and books are somewhat unique within the merchandising realm, because as opposed to toys or T-shirts, video games and books are derivative properties that often branch a story in a different direction. While still grounded in a movie, or the core iconography or characters of a franchise, games and books allow the creative freedom to explore different tangents and backstories, extending the core franchise (see also prior transmedia discussion). Of course, certain games and books are merely direct translations of a property into another medium, such as a novelization of a film, but the bigger a franchise and the deeper the fan base, the more options the rights holder has for creating new intellectual property grounded in, but not directly parroting, the underlying franchise (see also companion website for discussion of console games).

To an extent paralleling the move of toy companies to control more of their destinies—create channels and content to control more of the pie, rather than simply licensing their properties—book publishers have even set up their own film and TV divisions. Motivated by diverse factors, including watching the erosion of their traditional business, fearing pending additional disruption via e-book companies such as Amazon launching their own publishing arms, and seeing the lion’s share of profits from film adaptations of book series go to the studios, publishers such as Random House and Macmillan have launched in-house film and TV arms.39 Although there is logic in retaining more control, that control comes with a cost and associated high risk—it remains to be seen whether these traditional publishers will have the stomach or cash reserves for the roller-coaster process of financing films, and it is more likely that the experiments will first play out in TV, where there is lower risk and a natural fit for serialized stories. Given the overall challenges of the publishing business and the demise of major bookstore chains and specialists alike, the cycle of “ancillary markets” overtly feuling films that then fuel more ancillaries is unlikely to be commonplace and therefore disruptive to the traditional ancillary cycle. Publishers have done quite well historically with the symbiotic relationships of launching properties (from books) and creating properties (novelizations) tied to Hollywood, and the associated risks and costs in the name of hypothetically increasing profits is probably too big a bet outside the companies’ core expertise. Moreover, there is an unspoken snobbery in the book world, where the written word, so engrained for millennia in culture, is perceived either as a higher art form or a more learned form of intellectual property; accordingly, licensing rights to a hit novel is seen as opportunistic capitalism, while consciously targeting film has a whiff of debasement to the purists—meaning development of films within venerable publishing houses is apt to face cultural hurdles.

Growth of Social Games and Importance of Data Analytics

Zynga, which went public with a market capitalization more than $7 billion in 2011 (before its stock fell severely back down to earth in 2012), in many ways defined the social games space. Moving beyond its success with traditional games (e.g., poker) and themes (e.g., Mafia Wars), Zynga created original properties such as Farmville, CityVille, and Empires & Allies, leveraging a model utilizing database/customer mining, a freemium economic model, viral growth (as an almost positive parasite feeding off of social network traffic and interactions), and virtual goods. The power of the model not surprisingly spawned other social games companies, with Playdom gobbled up by Disney, Electronic Arts acquiring Playfish (which went on to launch the hugely successful The Sims Social, extending The Sims brand into this realm), and core-gamer focused independents (Kabam) raising venture capital in amounts exceeding what many IPOs generate. I do not plan to present a case study of or otherwise analyze Zynga or other social game companies; what I do want to highlight are some of the underlying metrics that make it and other social games companies tick.

The Zynga model, grounded in data analytics, has the potential to upend traditional metrics because these companies have tapped into the Holy Grail of customer engagement: networks and Hollywood do not know who their end customer is and rely on statistical samples such as from Nielsen to approximate consumer adoption and engagement, while social games develop a direct personal relationship with their consumers. Social games companies know who you are, can market new games directly to their user base, and can segment their marketing and offerings to users’ specific behavioural patterns. A good example is the release of Empires & Allies: because of Zynga’s customer database, it was able to report an astonishing 21 million-plus MAUs 20 days after launch in June 2011 (see below for a discussion of MAUs and metrics).40 What would Warner Bros. have paid with a film series such as Harry Potter to be able to directly market and engage with potential viewers based upon whether it knew that you had seen the first movie, the prior two, all priors in the series, had bought X items of merchandise …? Think about the discussion in Chapter 9 regarding trailering, which is trying to match demographics to target awareness, in an attempt to break down the barriers inherent in experience goods—how valuable would it be for a studio launching a new film in genre X, starring actor Y, to be able to directly market to the specific individuals who had watched/rented/bought a similar film that the studio is using to identify its target market? This is the power of Google and ad targeting brought to bear on the experience good quandary at the microscopic level of the individual.

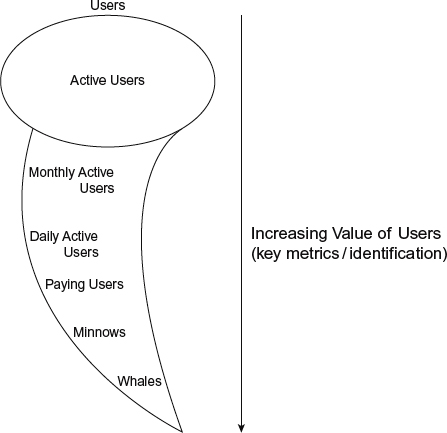

Social Games Metrics

The metrics behind social game monetization are relatively straight-forward. In simple terms, social games focus on segmenting populations, much like traditional loyalty rewards programs, to create a funnel optimizing revenues (see Figure 8.3). Imagine a tornado, and at the top where the cylinder is the widest is the total population of users who have ever tried a game. How to measure this total population is a function of how a service or site captures registered users. For traditional games, this tends to be counting client downloads of associated software; for social games, the measuring stick is similar, but because they are browser or app-based, it is usually expressed in application installations. From this base, the key metric is then defining from whom this population of “registered users” can then be defined as active users. There is no precise definition of active users; however, because companies (and the industry, in terms of leaderboards) track users on a daily and monthly basis, an active user is usually quantified as an individual that has taken some action to be meaningfully engaged with the game (product) within a one-month period (hence the often-quoted category of monthly active users, or its acronym “MAUs”). What that user has to do within a 30-day period to be labelled “active” is somewhat murky; ideally, he or she should have logged into the game and spent some de minimis time playing. By defining active users, a company automatically also defines inactive users, and in theory the registered users can be segmented into MAUs, those who are active but not on a monthly basis (have not lost them entirely), and truly inactive users (remember, the inactive can still be an important basket to track, as companies have a 1:1 relationship with them, and it may be that they do not like one game, but are participants in another).

Daily active users (“DAUs”) are then a subset of the MAU base, with the calculation not exact (based on averages), but still precise in that it is simply a tracking/database management issue to identify those participants who are engaging daily. Akin to theatrical box office, these top-line numbers of MAUs and DAUs are publically reported by the bigger companies, and available on sites such as www.appdata.com. These numbers are then used to create leaderboards, and report relative positions on a daily and weekly basis, enabling rankings on both a per-game and per-developer (publisher) basis. Although tracking very different elements, the net result looks a lot like box office rankings, comparing films (what is up/down) and studios; rather than weekend box office, the reports are simply aggregating weekly performance. I have not looked into data in terms of what days are most important, but one can surmise that it is the inverse of box office; whereas box office is dominated by the weekend when people have free time to attend movies, social games are (to the disdain of employers) are often played at work with quick check-ins, and generate heavy weekday traffic.

All of the above is interesting, but falls short of the key metric, which is: Who is paying? Social games employ a freemium model, meaning participation is free, but once hooked in order to accelerate performance, move on, or enjoy the key features, it may be necessary to purchase something (e.g., a weapon, a character, a building); the trade-off is often time, but can also be a substitution for playing with a multitude of friends (as the games incentivize social behavior, to gain a level or complete some equivalent task to move on you may need to have three people join you; if you do not, then the equivalent of paying for a virtual friend to join you will suffice). Accordingly, the most critical metric is average revenue per user (ARPU). Again, how ARPU is calculated may vary. It can be calculated as total monthly revenue divided by the total number of monthly active users; for social games, the calculation, though, is often tied to DAUs (daily revenue divided by DAUs).

From this segmentation, companies then can delve deeper and look at the lifetime value of a user (LTV) and the average revenue per paying user (ARPPU). Lifetime value is simply an extrapolation of how long a user is expected to engage at a certain frequency and monetization rate, and can be calculated in accounting terms much like traditional forecasting. ARPPU is critical as it is capturing the amount of money generated per user from those users that actually pay (real dollars) during a defined period (can again, in theory, be tied either to daily or monthly use, but is almost always viewed as a monthly calculation, as focusing on people that pay everyday is slicing the pie to thin). Once again turning to our tornado, the paying user is the point at the bottom of the funnel. It is this bottom point that is the most important number, and that developers then segment into finer slices, trying to identify the most valuable of the valuable (again, think of traditional customer loyalty programs). The term of art that has developed for the most valuable of these paying customers is “whales”—whales are individuals that can spend thousands of dollars per month paying for virtual items. Different companies then attach varying thresholds, but, for example, whales may represent a small (but critical) fraction of paying users, often in a 10 percent or less range (e.g., could be 2–3 percent). The other 90 percent can then be segmented as well; if half of the paying users pay $2 or less per month (“minnows”), then the other 40 percent (given that 10 percent are whales) are in the mid range. This categorization can then be translated into ARPPU thresholds, such as whales may be those with a value of more than $X (e.g., $50 per month), etc.

How to manage the analytics then becomes as important as the measuring sticks themselves, as all numbers and averages can become misleading. A decline in ARPU, for example, may not be a bad thing if it is correlated with a significant increase in total active users (namely, less on average from an expanded base may generate more revenue). In the end, more users and more payers is everyone’s endgame at a macro level, with a focus then on monetizing the most valuable users (the whales). Because the business mode, though, is heavily dependent on mining the whales, it will be interesting to see if this remains sustainable, which in turn depends on the strength of product offerings. The natural comparison is gambling, but the “addiction” motivating players there is true money, while the payoff in social games remains virtual and status (leaderboard) oriented. Logic would argue that a business built on maintaining cash flow from a couple of percent of users is subject to upheaval, and the success to date of the leaders has been because of early entry and building remarkably large funnels.

Figure 8.3

On top of these numbers, companies then layer on traditional market segmentation such as age and gender, and can run reports that will show X percent of revenue comes from women between 25 and 40 who are DAUs. These trends can then be correlated with specific actions taken (types of virtual goods bought, areas visited). It is not difficult to see the possible permutations, and the value in managing the database both for monetization and for marketing. It is also an advertiser’s dream to have this level of data on customers interested in their brand (see below regarding implications for other media).

Films as Social Games

Not surprisingly, with the explosive growth of the social games market, creating a social game based on a film is a new ancillary exploitation. While these have been limited to date, this is a growing trend, as evidenced by social game-maker Kabam’s licensing deal with Warner Bros. to produce games tied to the new The Hobbit films. Venture Beat noted: “Kabam will make two multiplayer strategy games that will be free to play, where users play for free and pay real money for virtual goods. The Hobbit: Kingdoms of Middle-Earth will debut on mobile devices. The Hobbit: Armies of the Third Age will debut on Web browsers.”41

Sony, leveraging its animation and interactive units, sees similar synergies, and in fall 2012 announced the launch of a Facebook game The Hotel Transylvania Social Game (www.facebook.com/hoteltgame) tied to its animated theatrical film Hotel Transylvania.42 For the films, these efforts provide, at minimum, a marketing boost and viral reach through social media—in the best case scenario, the studios gain marketing breadth, guaranteed licensing revenue (if a brand license, such as in the case of The Hobbit), and an upside linked to the success of virtual goods sales.

I asked Chris Carvalho, chief operating officer of Kabam and former head of business development at Lucasfilm, whether he saw projects such as The Hobbit as exceptions, or going forward we would see movies, and especially franchise-type movies, launch social games with the type of regularity that films tie into traditional console games. He noted: