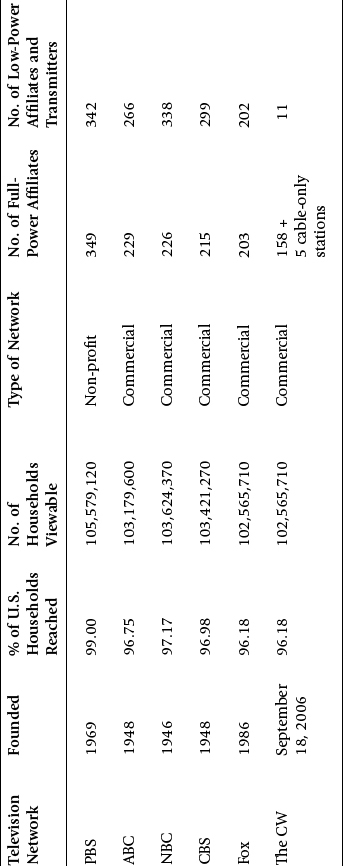

The TV market is both a primary and secondary platform for content. Although TV is traditionally thought about in terms of TV series and other made-for-television productions, TV programming is a quilt that also relies heavily on other product. Accordingly, beyond analyzing firstrun programming, to understand the entire economic picture it is also important to review how television garners revenues for films and other intellectual properties that can be aired on television but were not originally produced for television broadcast.

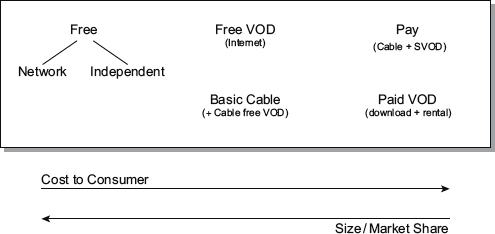

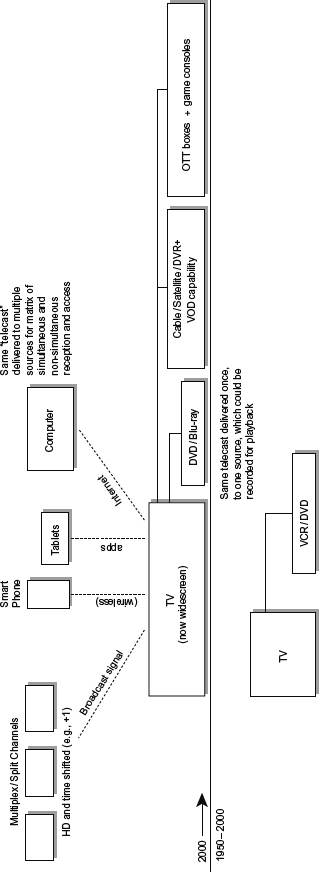

This chapter focuses on traditional television, namely free television (commonly referred to as free over-the-air broadcast television) and cable/pay television. New technologies, such as cable video-on-demand (VOD) and Internet/OTT streaming, are blurring the lines of what has historically been categorized as “television” (see Figure 6.1), and this blurring and the emerging new media platforms for TV programming are only touched upon here and then discussed in greater detail in Chapter 7. It is worth noting up front, however, that the very nature of what we perceive as “TV” is changing so rapidly that at the end of this century’s first decade, the landscape has completely transformed from what existed just a few years ago. Simply look at the new points of access that already exist (see Figure 6.2).

Against this backdrop, there are evident challenges, including windowing, as well as forecasting whether and how fast new media revenue streams will mature. I asked Gary Marenzi, former president of MGM Worldwide Television, as well as Paramount International Television, how he viewed this new landscape and how television distributors were adapting and tempering enthusiasm for new revenue streams versus the proven sources:

Figure 6.1 Types of Television

Digital/online-enabled platforms are becoming a major source of revenue for content providers, as more and more consumers (especially those under the age of 30) are utilizing their laptops, tablets, and smartphones as their primary sources of video content. This growth is obviously welcome and has helped to compensate for the decline in physical disc/DVD sales, but it requires the licensor to be extra vigilant in determining what rights are granted and for which exploitation windows. Obviously, licensors want to maximize their revenues from traditional sources like free television, so they’ll protect these traditional windows against overexposure by other media. But as media licensing opportunities continue to grow, the major content providers will stir up competition for pricier, exclusive windows regardless of the delivery configuration. The key for content providers is to maintain the value of their programming for every potential audience, so that priority will not change no matter how many new distribution options emerge.

Figure 6.2 The Shifting TV Landscape

Table 6.1 Table of Broadcast Television Networks

Data from Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_United_States_over_the_air_television_networks). Excludes My Network TV.

Free Television (United States)

Free Television Market Segmentation

Free National Networks

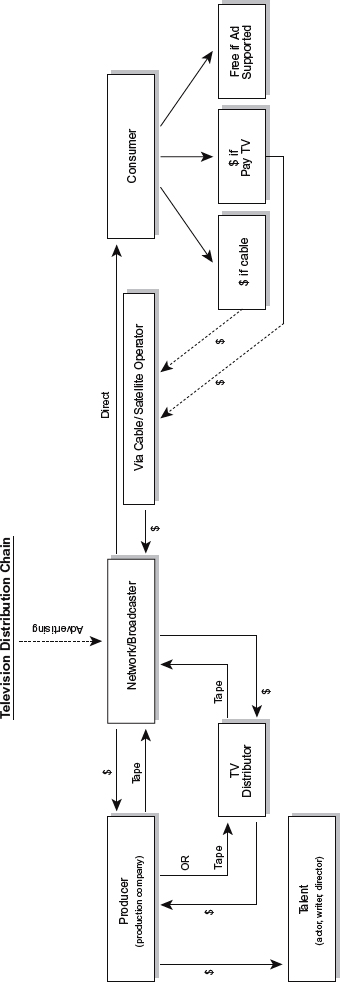

The market is divided into terrestrial over-the-air national networks (NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and The CW) and cable or satellite-delivered television stations. Networks are somewhat complicated entities, however, in that a network is really a grouping of local television stations that are either owned by or affiliated with the parent network company. The FCC regulates station ownership to protect against the concentration of media ownership within markets, a construct that may become moot as market shares continue to erode and access to media from online and other sources becomes ubiquitous. There are several regulations, but the critical ones governing television station ownership are:

■ National TV Ownership Rule: Prohibits an entity from owning television stations that would reach more than 39 percent of U.S. television households.

■ Local TV Multiple Ownership Rule: Allows an entity to own two television stations in the same designated market area (DMA, as defined by Nielsen Media Research) provided threshold minimum of other stations in the market remain and at least one of the stations is not ranked among the four highest-ranked stations in the DMA.

■ Dual TV Ownership Rule: Prohibits a merger between or among these four television networks: ABC, CBS, Fox, and NBC.1

Accordingly, the “big” networks are an aggregation of owned local TV broadcasters and affiliated stations, which cover all the major DMAs and reach nearly all the potential households in the United States (see Table 6.1). (Note: While reach has been relatively constant, it is interesting to note that services such as Nielsen have reduced their counts of TV households, a fact attributable to a census shift to the Web and evidence of cord-cutting (see Chapter 7); the reduction by Nielsen of households in 2011 was the first downsizing of total households by the ratings agency since 1990.2)

The “network” only programs a certain amount of airtime for simulcast on a national basis, which generally includes the national news and a primetime schedule of three hours in the evening. In terms of original programming, this translates into around 22 hours per week (three hours Monday–Saturday, four hours Sunday, excepting Fox, which broadcasts an hour less in primetime). This is among the reasons why NBC’s announcement at the end of 2008, amid the steep economic downturn, to eliminate original scripted programming in its 10:00 p.m. hour (EST/PST) was so dramatic (shifting a new Jay Leno talk show to its third primetime hour); this represented a shift of five hours out of 22, nearly a quarter reduction in original programming. (Note: The move, leading to a ratings decline, was generally considered disastrous and was quickly abandoned.)

The affiliates are generally obligated to run the network programming during these hours, but for the balance of the schedule they have a measure of flexibility whether or not to take the network-offered programming. The network actually markets and sells to its affiliates, trying to convince them to come on board for its slate. Economically, there are strong incentives to stay consistent with programming: the local affiliates gain the benefit of the brand (e.g., ABC or NBC), and the more shows it programs from the parent, the stronger and more consistent the brand. From the network’s standpoint, it wants national coverage for its programming and will therefore incentivize the local stations to stay loyal to its slate.

Local Independent Stations

Alongside affiliate stations that make up a national network, there remain many local independent television stations. The recent disbanding of the WB and UPN (2006) for the new CW network freed up several local affiliates, creating a boon for the independent market, which for years had been in decline. In the 1980s and the early 1990s, there was a plethora of strong independents, fueling off-network syndication opportunities, but the growth of networks such as UPN, WB, and Fox gobbled up the prime independents and relegated much syndication to an afterthought following cable options.

Cable Networks

There are currently over 200 cable stations in the United States, with toptiered channels bundled in “basic” carriage packages such that popular networks (e.g., Discovery Channel, ESPN, TNT, and USA) are provided in the overall fee charged to the consumer. This is distinguished from “premium cable,” for which the consumer pays a direct incremental fee for access to specific premium channels such as HBO (“premium pay cable”).

With the increased penetration of cable and satellite, many larger media companies have diversified programming by creating niche or specialized channels, and, as in the broadcast space, the independents have largely been consolidated. Examples of cable networks with national reach that are part of larger media groups include USA, Syfy, and Bravo (under the former NBC-affiliated family, and now all part of Comcast); Comedy Central, Nickelodeon, Spike, MTV (under the MTV Networks/Viacom family); CNN, TBS, TNT, TMC (under the Warners family); Fox Sports, FX (under the Fox/NewsCorp family); and ESPN, the Disney Channel, and the ABC Family (under the Disney umbrella). A good resource for television programming issues and for identifying a complete list of networks is the publication Broadcasting & Cable (see www.broadcastandcable.com, which lists upwards of 250 channels/networks). Beyond the pattern of large media producers developing or acquiring cable outlets for their content, it may be a new trend to see pure-play cable operators owning the cable networks carried over their pipe, in essence incubating their own viewers. Comcast, for example, before broadening its holdings with the acquisition of NBC Universal and its affiliated networks, was the parent to a variety of smaller services, including the Golf Channel, E! Entertainment, G4 (merged with the acquired Tech TV), and OLN (Outdoor Living Network, rebranded Fine Living).

Free Video-on-Demand and Internet Access—What Does Free TV Mean?

It used to be that “TV was only TV,” but with the advent of advertising-supported Internet access, such as offered by Hulu, and cable-free VOD (FVOD), the lines are blurring. In contracts, attorneys have to grapple with whether TV should be delineated by delivery mechanisms (e.g., analog, digital, free-over-the-air, terrestrial, satellite), and now dealmakers and attorneys alike need to categorize Internet streaming and other on-demand access. If a network such as NBC makes a show available for free Internet access on a non-NBC-branded site such as Hulu, or ABC makes a primetime show available via abc.com, or CBS makes its primetime series available for free viewing on cable free-on-demand, how should these be characterized?

As a consumer, you can access Glee, or CSI for no additional charge and watch the same programming with the same, or in most cases fewer, commercials. Because the start time for access is in the viewer’s control (and the site even perhaps embedded into a personalized page on a social networking website), it is a form of VOD; moreover, because this VOD is not transaction-based (i.e., no direct fee to the viewer), but is advertising-supported, it is coming to be known as advertising-supported VOD (AVOD), a subset of FVOD. (Note: See Chapter 8 for more discussion on transactional VOD.) Whatever the label, free viewing at one’s election is competitive with free viewing in accordance with a broadcaster’s schedule.

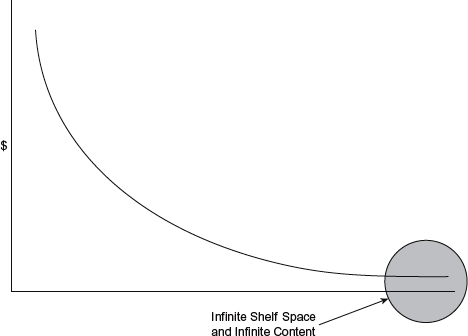

Free TV is therefore becoming categorized not so much by where or how one watches, but whether the content is TV-branded and -produced (“premium content”). In the future, free TV will ultimately only mean programming broadcast on TV (or perhaps debuted or simultaneously launched on TV) in addition to being made available via other outlets, thus turning everything on its head. Today, we think of the other markets as emerging and competitive to TV, but if and when content is everywhere (and, by and large, the market is already close to this point), then free TV will become the limiting, not the defining factor, because unlike other platforms, broadcasters have retail-like limited shelf space: just compare 22 hours of primetime versus an infinite range of choice on-demand or via the Internet. The fact that a program at least was aired or launched on TV, or was produced for TV, may become the defining element of whether it falls within the notion of TV at all.

Metrics and Monetization Challenges

It is worth circling back to the discussion in Chapter 3 regarding the challenge of pricing advertising, and the difficulty of reconciling online versus offline pricing—in some ways, it is almost as mystifying as international currency conversions and trying to find equivalents, given many moving parts. The issue is important in the FVOD context because major cable operators are straddling the fence, pricing in one way now while looking to major growth and an upside if they can coax the ecosystem into capturing value via increased VOD viewing accompanied by dynamic ad insertion. U.S. cable giant Comcast is a good example. Speaking at a Broadcast & Cable summit, and noting that Comcast anticipates VOD advertising impressions on FVOD content to increase tenfold between summers 2012 and 2013, one of Comcast’s executives noted: “We have 400 million monthly VOD views on Comcast. I’d love to have a dollar for every view.”3 FVOD revenue growth is enabled by dynamically inserting advertising into content called up by users, which makes the viewing experience feel more like live TV (as ads are not embedded in the content, creating the same repetitive loop each time a program is called). The catch is that the value of viewing those ads is still generally monetized via ratings, and captured within Nielsen Live+3 ratings windows; however, with dynamic advertising insertion and the ability to monitor by user, people are now starting to track data in different ways and looking at online impression metrics. The industry simply needs to rationalize and harmonize the systems, and once everyone can obtain consistent and reliable data from VOD sources (i.e., set-top boxes in terms of cable), then arguably different metrics than estimated (and aggregated) ratings ought to be used for valuing those VOD views.

This challenge was further highlighted in Chapter 3 when discussing the underpinnings of ratings, and the challenge of capturing downstream viewing from sources outside traditional TV, given the fast growth of watching via a myriad of devices, including game systems, tablets, and phones. Nielsen talks of the shift in “appointment viewing” whereby, historically, viewing and therefore ratings were grounded in capturing views at a particular place and time (with live sports being the prime example). However, they have asked the obvious question as to what happens when viewers can freely time-shift to when they want—how much viewing is taking place outside both the traditional metrics (“live”) and then outside the “catch-up” window captured generally as Live+3 and at the outside as Live +7? Citing a new National People Meter Panel that is being trialed, Nielsen has reported findings that “just over five percent of viewing is happening in this beyond-7-day environment, with less than one percent for syndication. In fact, some of the top shows are adding up to an entire rating point in this expanded period.”4 My guess is that this 5 percent is well underreported because metrics have not been reliably developed to capture the plethora of devices where people are actually watching, and that the sampling is too dependent on traditional streams from DVRs, where catch-up started and is still most prevalent. The challenges are daunting in terms of harmonizing ratings and metrics, but no doubt more and more content is being consumed both off-TV and later (whether via one-off catch-up or emerging trends of binge viewing, whereby viewers will watch a series in marathon fashion). (See Chapter 7 for further discussion.)

Historical Window Patterns and New Technology Influence on Runs

The market for feature films on TV has historically been very strong, and for years a key sales benchmark was a license to one of the major national networks. In the best of scenarios, the market even provides four successive TV windows, allowing for millions of dollars continually flowing in for well over a decade:

■ 12–18-month window on pay television (e.g., HBO, Showtime, Starz)

■ 3–4-year window on network TV (e.g., NBC, ABC, CBS, Fox)

■ multi-year window on cable TV

■ multi-year window in syndication.

(Note: As discussed later, four windows today is extremely rare.)

Assuming this historical pattern, a theatrical feature film will typically be licensed to a broadcast network for debut approximately three years after its theatrical release. This allows an exclusive period for the theatrical run, followed by the primary video/cable VOD window and a pay TV license (see Figures 1.8 and 1.9 in Chapter 1). Up until the TV landscape shifted dramatically (see Figure 6.2), the “network window” was generally the most lucrative, as the networks simply had a larger reach and audience share, and could therefore pay more with the larger advertising revenues earned. To the extent value is allocated over runs, the initial airing would command the greatest value because audience ratings usually show a decline with each successive airing. Accordingly, network licenses are customarily for relatively short periods and limited numbers of runs, such as for three or four runs over three or four years. Depending on the film, the first run, if not all of the runs, will usually be in primetime.

The Internet and digital technology are complicating even this relatively simple construct, as the definition of a “run” (i.e., telecast) is transforming. If a broadcaster has a multiplex channel, such as NBC and NBC HD, are simulcasts on each only one run? What if there are time-delayed digital channels where the entire channel is shifted an hour or two (e.g., ITV + 1), thus expanding the hours programming is broadcast (Program X is on at 9:00 p.m. on Channel Y, and again at 10:00 p.m. on Channel Y + 1, with Y + 1 the exact feed/programming as Y, just shifted back an hour). Is the + 1 run considered part of the other run, or separate? And, finally, what about free streaming VOD repeats on cable or the Internet, where a show may be available for a limited time (sometimes referred to as a “catch-up”) after the TV broadcast, allowing viewers to see the show if they missed it live or did not record it? Are catch-up runs separate runs, or is a run the live broadcast plus a week’s catch-up access?

Setting the evolving and boggling matrix of the definition of a run aside, in certain instances, with exceptional films, the license may specify exact airing windows such as around a holiday period or in a cross-promotional window if the movie is tied to a larger franchise. This was the case with Steven Spielberg’s classic E.T., where Sears sponsored the broadcasts and the film was licensed to play as a perennial on Thanks-giving. In the instance of a film series, such as James Bond, Star Wars, Batman, or Spider-Man, the license may be structured (or broadcasters may simply structure their schedules) so that airings take place around the promotional window for an upcoming new film in the franchise. Some believe that such an airing could detract from the theatrical release, but others ascribe to the theory that the TV broadcast helps cross-promote the film, and the film’s marketing platform, in turn, helps cross-promote the TV broadcast.

Decline in Ratings for Films on TV

It is an acknowledged fact that ratings for films on TV have declined over time, and there are several factors frequently pointed to explaining the slide. Among these are the growth of DVD, the growth of other media options such as the Internet, fragmentation of the TV market with the growth of cable, waning tolerance for viewing films with commercial breaks, the ability to consume the film earlier via ancillary platforms such as VOD and PPV, the changing profile of network scheduling and programming (e.g., reality craze), and, of course, piracy.

It is no doubt also true that before the growth of the home video market, TV had a more dominating impact: there was a large audience that had never seen the movie, and no matter how big a film was at the theater, the reach of tens of millions of eyeballs on TV inevitably dwarfed the numbers that had physically seen the movie in cinemas. With movies selling in the millions across downloads, digital lockers, and DVDs, and the expansion of ancillary windows/access, including VOD, allowing earlier consumption, clearly prior exposure has contributed to the decline in ratings of films on TV. In the 1980s when a film played on television, this was its first and primary exposure after the movie theater; now, however, by the time a film is on free television years downstream from its theatrical release, there have been innumerable opportunities to “consume” the movie on a variety of platforms (and, regrettably, both illegally as well as legally).

Shared Windows, Shorter Network Licenses, and Clout of Cable

With the decline in network clout and the growth of cable channels, the traditional sequential TV windows are becoming more of an historical artifact. There are instances where films go to network, and then cable, and then syndication; however, it is now common for cable stations to buy out network windows or to partner with networks on shared long-term windows with oscillating periods of exclusivity. The playing field is relatively level, and cable stations such as FX, USA/Syfy, TBS/TNT, Spike, Bravo, and the ABC family can compete with, and in cases are, the frontrunners to the networks, even in cases where the networks may be an affiliated sister company. Because the licensors are trying to garner the best deal for their specific film or package, the best option may cut across different studio lines and strange bedfellows can emerge.

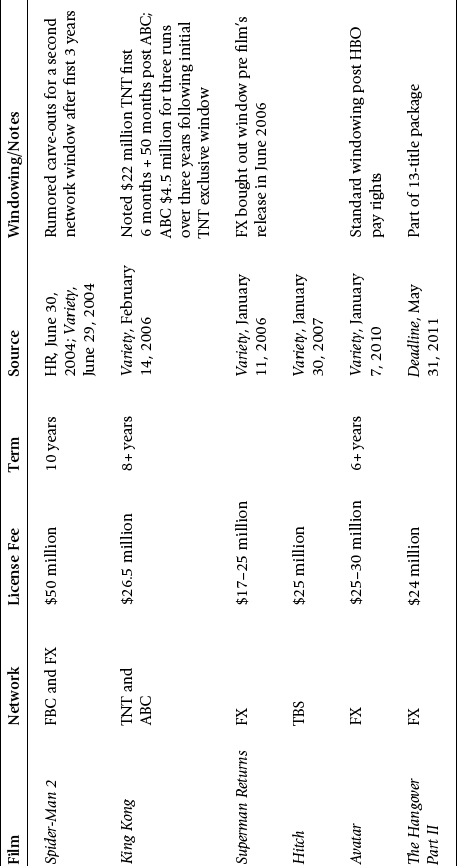

Ranges of fees are tightly guarded, but Table 6.2 outlines several high-profile deals typical of the market’s high end, and also illustrates how some films will share windows between cable and networks.

It is also worth highlighting that with the growing clout of cable, and especially in hybrid licenses where cable stations and networks may share runs, the licensed runs and period for networks are shrinking. Whereas it may have been typical to take three to four runs, scenarios now arise where a network may only take one or two runs.

Star Wars Example

I was personally involved in overseeing the licensing of the six Star Wars movies to TV. As of 2005, none of the films had aired on cable or syndication for several years, and Episode III, which was just launching in theaters, had obviously never been licensed to television. Given the unique nature of the saga, and knowing that there were no more sequel motion pictures planned for the future (at least that was the case at the time, before George Lucas turned the keys to the franchise over to Disney in his 2012 sale of Lucasfilm), it made sense to explore licensing all six films together. The highlight would be the television premiere of Episode III, supported with the first TV window for all of the films together. The final deal was made with Spike, at the time a relatively new cable network under the ownership of MTV Networks/Viacom, which catered to a male-skewing audience. Spike had rebranded itself as “the network for men,” in contrast to women’s branded networks such as Oxygen or Lifetime. The network had a variety of programming, but had been successful with franchise exploitation having been the home to the James Bond films. I cannot comment on the specifics of the deal, but it was significant, and Variety (without confirmation from either Lucasfilm or Spike) reported the package as being sold for $70 million.5

I relate this story not as a travelogue of deals past, but as an example of how interesting the TV market can be. At the outset of this deal, it probably would have been fair for analysts to speculate that the films would go to Fox, as historically movies of this stature would only debut on network; in fact, Episode I and Episode II had debuted on Fox. Cable had grown to a point, however, and the market had changed substantially enough that Episode III, the film with by far the biggest box office of 2005 ($380 million in the U.S. and $848 million globally) and among the top box office films of all time (as of 2005, number seven of all time), was licensed to premiere on Spike.

Table 6.2 Movie Licensing Fees

There is no doubt this formerly network-dominated business had experienced a seismic shift when The Lord of the Rings premiered on TNT, Star Wars on Spike, and Avatar on FX. This is also a sign of healthy competition as the big four networks and cable channels jockey for positioning and programming.

Economics and Pattern of Licensing Feature Films for TV Broadcast

Films were historically licensed in large packages. The size of packages could vary dramatically, from a few films to hundreds—a traditional studio package of films would often include 25 or more films. A buyer would acquire all the titles for a “package price,” with the titles having (usually) common numbers of runs and a common license period. There were always a couple of key lead titles, and buyers would be faced with the dilemma of potentially having to acquire a bunch of secondary titles simply to acquire the few titles they really wanted to program. With deals often going out several years, and with lots of airtime to fill up, this scheme satisfied buyers and sellers for years. The top pictures would be programmed in premiere slots, where premiums could be charged for commercial spots, and the other pictures could be used at off-peak times or even as filler. The art of valuing pictures within a multiple-picture package lies somewhere between absolute logic and litigation.

Packages are still common, but as buyers have become more selective, the number of pictures in those packages has shrunk, and the economics are more closely tied to true per-picture valuations.

So, how do you value a license?

Runs and Term

The most critical elements are the number of runs and term. There are certain industry-accepted benchmarks, and the jousting is then within these parameters. As noted previously, network television licenses are usually for a small number of runs such as three or four. This is largely due to the fact that, as earlier discussed, the definition of “network” accounts for those hours that are programmed by the network as opposed to given back to the affiliates; this inherent limitation puts a cap on inventory and programming space. A second limitation is that films are long—with commercial breaks, they take up a minimum of two hours of programming time, and can take up to three-hour blocks. Completing the matrix is the fact of diminishing returns: ratings typically decline with subsequent broadcasts, echoing the general TV pattern of higher ratings for new episodes/programs than for repeats.

Add up the factors of: (1) diminishing ratings with repeats; (2) limited inventory; and (3) requirement of large chunks of prime programming inventory space, and what you get is the need to space out broadcasts and cap runs. It does not really help to have the right to broadcast a film on network 10 times in three years because the network would never allocate that much space; the opportunity cost of foregoing a show that would likely draw higher ratings would force the network to omit runs. Moreover, for the licensor, if a film was played too frequently and the overexposure caused a severe dip in ratings, then the future value would be diminished. Everyone would lose.

The result is a mutual desire to manage runs in a way that maximizes ratings and returns. As a rule of thumb, playing a film on network, on average, more than once a year starts the downward spiral; accordingly, most network deals call for a couple of runs, and sometimes up to four, over a period of time that allows breathing room of, on average, at least a year between runs. A traditional network deal may therefore be structured as three or four runs over three or four years.

Cable licenses are more complicated, for there is more inventory space and the smaller audience share lends itself to more repeat viewings; cable, after all, grew up as a bastion for reruns, and only in recent years have cable networks invested substantially in original programming to differentiate themselves. The pattern in cable is more dependent on the niche and individual station philosophy, and some stations will literally play programming to death. What is typical across all groups is that the average number of runs is substantially higher—it is not unusual to see film deals with 10 or more runs of a title per year. This allows the cable network great flexibility in programming, and enables customized blocks, such as marathons, weeks focusing on subject matters, retrospectives, etc. The cable station is often branded as the “home of X,” and for that to ring true it needs to appear enough to validate the identity. Airings once a year or so do not make sense, nor would there be (potentially) enough programming to fill up the schedule. As networks mature, they often realize that they have the same vested interest in not overexposing a property, and balance is ultimately struck.

It is important to note in this context that a run may not be what one expects of a single run; namely, before the layer of complexity created by Internet VOD or multiplexed channels, cable and pay TV required nuances on the notion of runs. A network run will be just as it sounds: a simultaneous broadcast aired by its network affiliates, run one time during the day. For cable, however, given the lower penetration and repeat programming as part of the landscape, runs may be defined similar to a pay television context with the use of exhibition days. An exhibition day is a 24-hour period (very specifically defined in a contract; for example, 12:00 a.m. until 11:59 p.m., and then within the box defined as an exhibition day there may be multiple runs granted). Accordingly, the cable broadcaster may have the right to broadcast a title two or perhaps even three times within that single day. Often, these runs are placed at unrelated times to fill up programming space, but in other instances there will be back-to-back runs (often marketed as an “encore” performance). The theory is that no viewer would watch the program twice in a day, and that the multiple start-time schedule will not undermine the value: after all, there are only so many exhibition days allowed. So long as the number of exhibition days is within customary bounds, and likewise the number of runs permitted within each such exhibition day is standard, then this practice is generally accepted.

Setting License Fees

It is only after sorting out the runs and years that it can then make relative sense to value the corresponding license fee. That is why it is so difficult to make direct comparisons on TV deals: the playing field is not level. It is not like dealing with DVD units, where there are bragging rights to absolute numbers (although this has its quirks, as discussed in Chapter 5, with performance influenced by pricing, returns, and inventory management) or the egalitarian barometer of box office. When you hear about a license value for a TV deal, it has to be put in context of how many runs, how many years, and if it was a stand-alone or an allocation of some sort was involved (now only imagine the complications wrought by trying to factor in online catch-up). Moreover, in a world of relationships and horse-trading, there may be political or timing elements that could further influence values.

Stripping out these other considerations, and looking purely at the underlying economics, the principles of valuing the license fee then becomes straightforward. The licensor will look to competitive product or historical licenses to set a range, and the licensee broadcaster will be running numbers on potential advertising revenues. The deal can thus be looked at on a macro level in terms of the gross fee, and then also be validated bottom-up by analyzing on a per-run basis (either straightlining license fees per run or imputing a certain discount after a certain number of runs). At some level, this can be overanalyzed, because a buyer and seller will be negotiating here in a classic fashion trying to find common ground. Are you going to agree to $50,000 per run or not?

To gauge whether $50,000 per run is fair value, if one side perceives there is too much of a gulf and they cannot agree on terms, then the negotiation may take on factors that apportion risk. This often takes two forms. First, a licensor may agree to a percentage of barter, such as a deal that is part cash and part barter. In this scenario, a certain minimum guaranty is locked in for security, and the balance is tied to the ad sales. This is a cumbersome direction, for it requires being in the loop on the ad sales front, as well as the determination and cost of potentially auditing the revenues. Another, frankly easier path may be tying overages or underages to ratings performance. If the fees are ultimately tied to a certain expectation level, then tying a bonus to over-performing should protect both sides; the licensor will win by protecting an upside, and the broadcaster can easily afford the upside if they have earned a premium on the ad sales. Both of these scenarios significantly complicate a deal from a reporting, managing, and trust perspective.

Another method of valuation is simply to quote an industry-accepted range. On hit films, it was sometimes quoted as a “rule of thumb” that the license fee should be in the range of 10–15 percent of domestic box office; however, this percentage cannot be relied upon as an accurate benchmark, and to the extent there is a benchmark range, it tends to move over time. In the case of Superman Returns, for example, Variety said of FX: “The network has agreed to pay Warner Bros. Domestic Cable about 12 percent of the eventual domestic gross, with a cap at between $17 million and $25 million, depending on the contract’s length of term and on whether Warners finds another buyer to share the window with FX.” Although an older example, in reporting a license for War of the Worlds, Variety referenced this barometer in the context of a reputed $25 million fee:

That’s a much lower stipend than the 15 percent of domestic box office, which used to be the benchmark for a successful theatrical-movie deal in the network window. But times have changed. Since War of the Worlds has grossed more than $230 million domestically, 15 percent would come to $34.5 million—an impossible figure for distributor DreamWorks to draw in a sluggish broadcast and cable marketplace for theatricals…. Bowing to the new reality, distributors have put a cap on the total license fee, which can start as low as $22 million and rise to as high as $27 million a title, unless the buyer gets more runs and a longer exclusive license term.6

Further indicating that there is likely an artificial ceiling in the market, Broadcasting & Cable magazine, in describing how FX was recently dominating the market, acquiring 28 of the top 50 box office titles in 2011 (including Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo as part of a $100 million 19-film deal), noted in the context of a further acquisition of 21 Jump Street and The Lorax that: “Basic cable networks tend to pay 8 percent to 12 percent of domestic box office for premiere rights to theatricals.”7

A final twist is licensing titles across channels within a larger group. If a particular film has crossover demographic appeal, together with a strong enough brand identity, then there may be a desire to play the title across multiple group-affiliated networks. This obviously adds another wrinkle to the analysis and value for runs. Moreover, this is an area where analysis paralysis can loom, and from a macro point of view many will simply split this into network versus cable; namely, how many aggregated cable runs are required across various cable outlets. It may be that certain discounts are taken, or that certain outlets are either ignored (given limited reach) or excluded on grounds of fit (“I do not want X on Y!”). The primary impact of aggregating potential licensees is that the fee will usually increase, given the greater exposure, and the time of the license will also be lengthened to allow for the title to be cycled through the different outlets without over-saturating exposure both on a single outlet and across the group. While it was only the syndication market that traditionally had very long licenses, one may now see 10-year licenses in this context.

First-run TV series tend to follow a regular cycle of development and launch tied to network seasons. Although the growth of cable, including powerful pay networks such as HBO, have altered this, and some networks have gone to a year-round launch calendar, most network shows debut in the fall and are committed to following screenings of pilots in the spring.

Pitch Season and Timing

Pitch season is traditionally in the fall. The new network season has launched and, within a short span (in many cases, within the first two to three episodes), the broadcasters are already starting to evaluate which new shows will survive and whether to consider mid-season replacements.

After scheduling pitches (“pitch season”), the networks will then decide which ideas to green-light for a script, with the network’s approval of the writer. The script will then be written later in the fourth quarter so the script would be ready to take to pilot in the new year. There is a brutal winnowing down of material, and only a small percentage of pitches are commissioned for scripts, and an even smaller percentage of scripts are then produced as pilots. The ratio can vary dramatically from company to company, with the economic incentive to maximize the percentage of pilots made from scripts commissioned. The Museum of Broadcasting once pegged the ratios as follows: “few scripts are commissioned, and fewer still lead to the production of a pilot—estimates suggest that out of 300 pitches, approximately 50 scripts are commissioned, and of those, only 6 to 10 lead to the production of a pilot.”8

Pilots

Although expensive to produce, as discussed in Chapter 3, pilots are an efficient means to test a concept and evaluate a show before committing to a full series. To a degree, this solves the problem faced by theatrical films, and inherent in experience goods, of having to complete the movie before it can be screened and tested; theoretically, a pilot dramatically decreases the risk on a per-property basis because there is enough information to make an informed decision, yet the show is not so far along that it is too late to make changes.

Because pilots are the guinea pigs of a series, experimenting with location, premise, cast, timing, etc., they tend to be significantly more expensive than later episodes. Once a show finds its rhythm, it should become more efficient to produce (but for escalating talent costs), as episodes are produced in volume, and upfront costs of sets, costumes, and infrastructure can be amortized over the run of series. Although the amounts are now dated, the Museum of Broadcasting noted the following regarding costs and the risks at stake: “In the early 1990s the average cost for a half-hour pilot ranged from $500,000 to $700,000, and hour-long pilot programs cost as much as $2 million if a show had extensive effects.”9 Today, the cost of pilots is a multiple of those figures. In looking at the 2009–2010 pilot season, the Hollywood Reporter noted that with the downturn in the economy, the average cost of drama pilots had dropped to $5–5.5 million from a high of $6–6.5 million in 2008.10

Pickups and Screening for International Networks

The “network cycle” continues in the second quarter of the new year as network executives tinker with and test pilots with focus groups. By spring, decisions need to be made, and the networks elect which shows they will commission for their fall lineup. The timing is dictated by the “upfronts” (see more detailed discussion later, as well as discussion of emerging digital upfronts in Chapter 7), where the networks put on a dog and pony show for advertisers, unveiling their primetime lineups and securing large upfront buys for the bulk of the season’s airtime. Virtually as soon as the lineups are locked, the networks host screenings for international buyers; the “LA Screenings” occur toward the end of May following the network upfronts and comprise a week when international networks cycle through all the new offerings. The LA Screenings have evolved into a significant market, given the growing importance of global license fees and the need for key broadcasters to launch series on a nearly simultaneous basis to avoid devaluation from piracy and potential early online glimpses.

(Note: There are other forms of first-run programming, such as TV movies and miniseries, both of which have generally fallen out of favor given costs and general programming economics (TV movies, for example, are now more common on cable networks, such as Lifetime, that can both match programming to specific demographics and heavily promote and rebroadcast the programs given their 24/7 control of airtime and limited original offerings). Given that these formats have become relatively niche programming, I will not address here, but simply point them out as another factor in market segmentation, as described in Chapter 1.)

Syndication versus Network Coverage and Timing

Syndication used to be the Holy Grail for TV: once a program reached a certain number of episodes, it could be sold into syndication for fees that can dwarf initial licensing revenues, turning a deficit into profits. The traditional magic number for syndication is 65 episodes. This allows a station to run a program five days per week (“stripping”) for 13 weeks, corresponding to half of a network season (e.g., September–December); with repeats, this quantity provides adequate episodes to run a series daily throughout the entire broadcast year. Although this can still be true, the market has shifted dramatically from the 1980s and 1990s, when syndication was king. This is due to a number of factors: the elimination of the fin/syn rules (see the section “Impact of Elimination of Fin/Syn Rules and Growth of Cable” later in this chapter for discussion), the growth of cable stations acquiring programming that used to be the staple of syndication, and the shrinking number of potential syndication buyers overall (by network groups such as Fox and the WB, now part of CW, aggregating stations and taking key independents off the market).

Table 6.3 Ratings and Coverage of Syndicated Shows (2006)

Program |

Stations/% Coverage |

Ratings—AA % |

Wheel of Fortune |

488/98 |

9.2 |

Oprah Winfrey |

S21/99 |

7.6 |

Jeopardy |

464/98 |

7.2 |

Dr. Phil |

S23/99 |

5.6 |

Entertainment Tonight |

484/99 |

5.6 |

Judge Judy |

473/97 |

4.8 |

Seinfeld |

408/99 |

4.7 |

Friends |

404/99 |

3.9 |

Variety, December 18–24, 2006; AA average refers to non-duplicated viewing for multiple airings of the same show.

Before discussing these forces and the evolution of the market further, however, it is useful to clearly define syndication. Simply, syndication means licensing a program into the individual markets on a one-by-one basis. There are over 400 markets in the United States, and syndicators maintain dedicated sales forces to sell programming into individual stations. Table 6.3 illustrates a matrix of top-ranked syndicated shows, coverage achieved, and their ratings.

As discussed earlier, stations are either owned, affiliated, or independent; even affiliated stations have programming flexibility and only take a certain percentage of programs from their affiliated parent groups, thus having residual program slots to acquire other programming offered by the network (such as branded late-night shows or morning talk shows) or unaffiliated third parties. When all the network affiliates broadcast a program together, it reaches 95 percent or more of the potential TV households, thus creating the unique convergence of saturation market coverage and simultaneous broadcast. This is a cumbersome way, in essence, to stay live.

In contrast, syndication is the broadcast of the same program over non-affiliated stations at times programmed by the individual stations. Accordingly, it is possible in syndication to achieve the same market coverage and the same amount of time on the air. The profound difference is in missing that intersection of simultaneous broadcasts with full market coverage. This pseudo-live nature of a network broadcast is what makes it so powerful: the network can reach an enormous number of people with the same programming at the same time. This cross section allows for targeted marketing and scheduling, which in turn allows for targeted advertising. Despite the explosion of new media options, there is still no better way to reach a population of over 250 million people. Broadcasters know that a certain percentage of X demographic will watch the nightly news at 6:00 p.m. versus Y demographic for a sitcom in primetime. And the game is all about that sole fact: how many eyeballs of which type (here, young versus old, male versus female, kid versus adult) will see the program.

Syndication, in contrast, is still about drawing eyeballs, but the task can be more challenging when the promotion is solely at a local level.

There is no absolute magic threshold for coverage, but there is a certain quantum of coverage that rises to the level of “significant.” That benchmark is usually in the 70 percent or more range. The composition of the coverage is often a hodgepodge of stations. It could mean an ABC affiliate in Denver and Dallas, a Fox affiliate in Los Angeles, and independent stations in Kansas City and Seattle. There are sometimes certain station groupings, such as the former “WB 100,” that may license together, which can achieve a chunk of coverage in one deal.

Achieving a certain quantity threshold of coverage is critical for attracting advertisers, as many will not consider a program that does not hit an internal mandated coverage threshold (e.g., 80 percent of nation-wide coverage). Beyond the absolute percentage, however, advertisers will look at both the quality of stations and the programming time. For a national buy, there will usually need to be a significant number of top stations in key markets. If, for example, there are no network-affiliated stations carrying the program in the top 10 markets (e.g., no network affiliates in Los Angeles, New York, Chicago), then it is obviously a hard sell. Sometimes this can be overcome with a strong enough station grouping, such as a percentage of Fox- or ABC-affiliated stations.

Because the syndication quilt will not achieve simultaneous broadcasts, advertisers will also be keenly interested in the time slots. It may be great to have a Chicago station, but if it is a CW station broadcasting a kids’ show at 5:00 a.m., then the value is clearly very different than had it been an ABC affiliate at 8:00 a.m. It is because of this particular challenge of trying to aggregate and secure advertising commitments across unaffiliated stations in less than full market coverage with non-synchronized broadcast times that anyone in this business needs a good advertising–sales team. The nature of the beast is such that it may be difficult or impossible to secure a national spot/advertiser, and that advertising needs to be sold on a market-by-market, broadcast-slot-by-broadcast-slot basis. Because syndicators may air a program more than once a week, the matrix of total telecasts becomes quite complicated to manage. (Note: See also Chapters 3 and 7 regarding the challenge of pricing fragmented online/Internet viewing, as akin to a form of national or global syndication, whereas traditional TV syndication sells advertising locally.)

Barter as a Solution to Fragmented Sales and Airings

Making this task of selling ads even harder is the speculative nature of viewership. Because of the fragmented placement, marketing can only be committed at the local level, and ratings are only meaningful within the discreet local market. Accordingly, what has emerged is a barter market.

The term barter syndication is often used in this context, and means a sharing of the advertising time. If a 22-minute program is shown in a 30-minute block, that may leave approximately seven minutes of advertising space to sell (excluding time reserved for station promos). The licensor of the program may “own” all or part of this time, and is betting on the fact that he or she can sell the space for better terms than he or she would otherwise receive for licensing the program outright. This is also a mechanism for the station to hedge its bets and lower program acquisition cost. It may be better for a station to pay $1,000 rather than $3,000 for a program and cede some advertising time to lower its costs.

In this instance, the station is obviously betting on a couple of factors. First, it is assuming that the value the licensor will achieve from selling the advertising inventory is less than the discount the station has granted. Second, the station is assuming that there is residual value/benefit to having the programming; it draws viewers to the station generally in the time period, viewers are not going to a competitor, and viewers may stay tuned in for other programming because of coming in the first place.

There are even instances of full barter, where the station pays nothing and the licensor achieves any and all financial benefit from selling the space it retains. In this situation, the station may reserve some spots and have a pure upside from selling inventory against no-cost basis. Of course, there are always opportunity costs, and the buyer needs to value whether another program would create greater ultimate value.

As a result of the complexity and difficulty of clearing markets, and then selling advertising across a scattered broadcast pattern, specialist distributors have evolved. Two of the powerhouses in this space, for example, have been King World (now merged with CBS) and Tribune; additionally, given the scale, companies will sometimes further partner with other specialists, as was the case of syndicating South Park, where one company was responsible for market clearances and another for the ad sales.

Barter to the Extreme—Paying for Blocks of Airspace

The ultimate barter arrangement is the full auctioning off of airspace. This tends to occur in a couple of niche areas, such as certain children’s programming.

A prime example of this practice was 4Kids Entertainment’s arrangement with Fox. When Fox Family was sold to Disney, Fox opted to shutter its Saturday-morning Fox Kids animation block and instead lease the space. It struck a deal with 4Kids, the company that represented the merchandise licensing rights to Pokémon (and certain non-Asian TV rights to both Pokémon and Yu-Gi-Oh!), where 4Kids paid Fox $25 million per year for the airtime; 4Kids then sold the commercial space within its half-hour block and was betting that either its annual advertising revenue would exceed the $25 million, or if it ran a deficit its merchandising sales would take it into profits. In essence, the company rented the commercial space, viewing the broadcasts as a giant commercial for the brand that would then drive non-TV revenue. Perhaps only in children’s programming, where robust merchandising programs may be a primary goal, can a producer set a strategy to use the show itself as a loss-leader to drive ancillary revenues. (See Chapter 8 for additional discussion of this 4Kids–Fox deal.)

Infomercials are another area where one sees negative license fees and full purchase of airspace. Here, a company is renting the airtime for a giant commercial. This presents even tougher economics than the 4Kids example, because an infomercial is not selling advertising against the airtime, and therefore needs to recoup 100 percent of the lease costs against product sales. At least in the 4Kids instance, there is the goal for advertising to recoup the rental costs, with the deficit in the worst case merely a fraction of the overall lease costs. For this reason, infomercials tend to air during inexpensive slots, because costs would become prohibitive during prime airtime.

First-Run Syndication and Off-Network Syndication

First-run syndication means programming produced for initial broadcast in the syndication market. These programs are often daily, unscripted shows such as talk or game shows (e.g., the original Oprah Winfrey show, Wheel of Fortune, Entertainment Tonight). In the 1980s, there was an upswing in the number of dramas that succeeded in syndication, with spin-off Star Trek series (Star Trek: The Next Generation and Star Trek: Deep Space Nine) and Baywatch pacing the market. (Note: Baywatch was an interesting case because it aired initially on NBC and was cancelled, but then continued with new episodes in syndication.) The nature of firstrun syndication shows also leads to longevity not seen in other programming—two of the most successful syndicated shows have been Wheel of Fortune and Jeopardy; both premiered in the early 1980s and have been running for roughly 25 years.

In contrast to first-run syndication, off-network syndication refers to the playing of reruns of hit shows after they have finished their network runs (or in the case of multiple completed seasons for long running series). This captures the category of when shows such as Seinfeld, The Simpsons, and The Cosby Show are syndicated to independent stations. As earlier noted, it is only the most successful of shows, those that reach more than 65 episodes, and more frequently crest 100 episodes, that have the awareness and stature to succeed in this market. Achieving this status, however, is the ultimate mark of success, and is where TV shows have their true upsides.

One of the most famous examples was The Cosby Show, which led the networks ratings race in the 1980s, and in the 1986 network season had a record 34.9 rating on NBC (representing 63 million viewers at the time) Time magazine noted: “The show’s success has created its own bonanza on the syndication market: The Cosby Show reruns, currently being sold to local stations, have earned a record-smashing $600 million, and the total could eventually top $1 billion …”11 This is the Holy Grail of television, and the success of The Cosby Show paved the way for its producer, the Carsey-Werner Company, to become one of the most successful independents in TV history: “Another hit show of the 1980s for Carsey-Werner was The Cosby Show spin-off A Different World, which aired on NBC beginning in 1987. The following season, 1988–1989, the company would accomplish the unprecedented feat of producing the year’s three highest rated shows: The Cosby Show at number one, followed by Roseanne and A Different World.”12

(Note: As an interesting footnote, the wealth created here allowed Marcy Carsey to partner with Oprah Winfrey and Geraldine Leybourne (former Disney and Nickelodeon executive) to found the Oxygen network, and Tom Werner was part of the group that purchased controlling interest in the Boston Red Sox baseball team.)

Aftermarket sales continue to be the lifeblood of television success today. The key market change is that whereas cable networks were originally simply competing with syndication for top programming, they are now the leading buyers. The Sopranos set a record, with an estimated $2.5 million per-episode license fee from A&E for an exclusive run off of pay TV (HBO). A few other examples, some also with fees greater than $2 million per episode, include: (1) Sex and the City to TBS for an estimated $700,000 per episode;13 (2) The Office to TBS and Fox-owned and -operated affiliates for $950,000 per episode ($650,000 per episode for TBS);14 (3) Law & Order: Criminal Intent to USA/Bravo for just under $2 million per episode; (4) The Mentalist for approximately $2.2 million per episode to TNT; (5) NCIS: Los Angeles for approximately $2.2 million per episode to USA;15 (6) Hawaii Five-O for approximately $2.1–2.5 million to TNT;16 and (7) The Big Bang Theory for $1.5 million per episode to TBS.17 What is interesting in the foregoing NCIS: Los Angeles example is that this sale was achieved during the first year of the series, long before there were enough episodes to be “stripped” into typical syndication. This type of move, while unusual, is not unprecedented, as strong brands with spin-off series have similarly managed sales during their first seasons (e.g., CSI: Miami and CSI: New York, respectively to A&E for $1 million per episode and to Spike TV for $1.9 million per episode).18

Online Services Now Changing the Dynamics

It was inevitable, with the growth of streaming services such as Hulu and Netflix becoming leading gateways for both on-demand and secondary viewings (and thus akin to new types of networks), that Internet-delivered services would start to compete with cable for programming in the off-network/syndication window. In 2013, CBS hit series The Good Wife was sold in a complex window for what was estimated to be $2 million per episode in what I can best describe as a “syndication-plus” license window. The show was sold to Amazon, Hulu, the Hallmark Channel, and basic syndication, in a divvying up that allows certain seasons to be accessed via Amazon Prime (commencing March 2013) Hulu Plus to offer seasons on its subscription service (commencing September 2013), the Hallmark Channel to air episodes on basic cable (starting in January 2014), and weekend broadcast syndication airings being sold in (for fall 2014 debut).19 The deal also has marketing implications, with availability on online services viewed as a potential catalyst for bringing in new viewers to current episodes. Deadline noted: “The rationale is that binge-viewing customers are so accustomed to such platforms, as evidenced by Breaking Bad on Netflix, it would send new viewers to The Good Wife’s original telecasts on CBS the way it happened with Breaking Bad on AMC, which has been sizzling since the series’ previous seasons became available for streaming.”20

(See Chapter 7 for further discussion of online streaming services such as Netflix and Hulu impacting television programming.)

Online’s “Short Tail” versus “Long Tail” and Impact on Syndication

The ability via the Internet to monetize the long-tail value of content sometimes leads people to assume that the long tail creates incremental revenue; however, that may only be true if there is no additional upfront exposure or what I will refer to as the “wide tail” (or the platypus effect discussed in Chapter 1). The increased access points for TV programming and the ability to easily see a show you missed via free Internet, cable VOD, and expanded video and over-the-top VOD offerings (e.g., Netflix, Amazon) leads to such front-loaded exposure that downstream values are inevitably poised to drop. This is due to multiple factors, including fewer viewers who are watching a show for the first time in a long-tail window and less repeat consumption with greater access to more new programming in the wide tail. In my first edition, I noted we were already seeing the impact on pricing and revenues, and further predicted that the overall pie would shrink if the nonexclusive value of the wide tail did not equal the prior exclusive value of the long tail. I asked long-term industry veteran and president of Fox TV International, Marion Edwards, about the new TV landscape and whether she sees the pie expanding from Hulu-type services or whether easy access is serving to undermine pricing for reruns. She noted:

There is no doubt that the world of “free on-demand” (FOD), now primarily referred to as AVOD (advertiser-supported video-on-demand), as well as SVOD (subscription video-on-demand) viewing, whether accessed on a network-branded website, or on OTT services such as Hulu, Netflix, Amazon, or any number of smaller local services, all delivered via various platforms to the ever-growing number of devices, is having a major impact on the traditional revenue streams associated with the distribution business. The obvious upside is that, in the AVOD model, these services give the advertisers “unskippable” ads (which makes those ads more valuable), the networks have found a new way to allow viewers to “catch up” with shows they may have missed, and the viewers can watch programs when and where they choose. The SVOD model allows for consumer consumption of entire series (binge viewing) quickly after the first network run had ended and has pumped important revenue into the distribution stream. The distributor, however, has the challenge of trying to make the program seem fresh and unique in a world where it has become ubiquitous, and to be mindful of the home entertainment value when consumers are very aware that programming is available for free quickly after telecast, and soon after first run on SVOD services. In addition, the new ask from broadcasters is to allow downloading for some period of time, instead of the streaming rights currently granted. We are already seeing the impact on the long-term value of TV programs in terms of relicense in the traditional aftermarkets. The emergence of digital terrestrial television channels as consumers of “library” series has helped retain value, but has not replaced the value of network relicense. How the overall economic model continues to evolve remains to be seen.

Impact of Elimination of Fin/Syn Rules and Growth of Cable

The huge off-network syndication revenues earned by producers such as Carsey-Warner were among the reasons that broadcast networks started to lobby against the elimination of the financial interest and syndication rules (fin/syn rules). Summarizing the history, the Museum of Broadcast Communications notes:

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) implemented the rules in 1970, attempting to increase programming diversity and limit the market control of the three broadcast television networks. The rules prohibited network participation in two related arenas: the financial interest of the television programs they aired beyond first-run exhibition, and the creation of in-house syndication arms, especially in the domestic market. Consent decrees executed by the Justice Department in 1977 solidified the rules, and limited the amount of primetime programming the networks could produce themselves.21

These rules were contested for years, with producers favoring fin/syn fighting the networks, and were eventually relaxed and then fully eliminated in 1995. One of the reasons for the elimination was a belief that media competition, including from the growth of the cable market, had weakened the networks’ prior dominance and that therefore the protections were no longer needed. This was true, to a degree. The combined TV market share for ABC/CBS/NBC in the time of the rules’ promulgation in the 1970s bordered 90 percent, but 20 years later in the mid 1990s the share had dropped into the middle 60 percent. Nevertheless, the fear of vertical integration by major media groups, and the difficulty for smaller producers to deficit finance series in the hope of hits that would pay for misses, remains a challenging reality for independent producers who want to keep the back-end/upside in their productions. How easy do you think it is today for an independent producer to land a show on NBC and maintain ownership in the backend syndication revenues that could lead to the type of upside reaped by Carsey-Werner on The Cosby Show?

Virtually any producer will lament that the result of changes in the fin/syn rules has been to shift leverage to buyers/networks. I asked Ned Nalle, former president of Universal Worldwide Television and executive producer of various series (e.g., Legend of the Seeker for ABC Studios, along with Sam Raimi, director of the Spider-Man films), if he agreed with this trend. He noted:

Mergers and relaxation of financial interest regulations have led to market concentration. Putting aside whether the quality of the content has improved, deteriorated, or stayed the same since the market contracted, it nevertheless means less competition among buyers for content. That means the leverage pendulum has moved decidedly over to the buyer, and away from the seller. It also seems to excuse that, absent more competitors breathing down his or her neck, a buyer can and will take more time to make a decision. The buyer will also exact more rights away from suppliers. It doesn’t mean that worthy shows won’t get ordered, and eventually be on the air. But shows may be commissioned for financial-interest reasons as much as creative or ratings merits. As the gatekeeper, a network can demand anything from an anxious producer, including distribution rights, financial interest, negative covenants, sequels, spin-offs, and certain protection before a producer might migrate a hit series to a network rival.

The TV business has always been one of deficits; namely, the license fees for a show rarely cover the cost of production, and the resulting deficit is hopefully made up in off-network syndication sales or other revenue streams such as DVD. This holds as true today as when the fin/syn rules were in force and Carsey-Warner was in its heyday. (Note: At that time, it cost approximately $500,000 per episode to make a standard half-hour comedy, which would typically run at a deficit of $100,000–200,000.)22 The only difference today is that the gulf has grown, with the cost of production generally rising more than corresponding license fees. This is not surprising, given the erosion of network market shares and in the increased competitive environment.

The macro picture is therefore similar to the motion picture business, where hits pay for misses, and success is based on a portfolio strategy. The buffer that has sustained the TV business recently is the expansion of additional revenue streams. In the children’s area, as described before in the 4Kids example, merchandising opportunities are sought after to recoup a deficit. With respect to live action, the growth of the DVD market for television series, now augmented by online and portable revenues, such as downloads to tablets, VOD access via cable, and OTT services, has created an additional buffer to projected deficits following initial broadcast license fees. The New York Times, in part quoting 20th Century Fox Television co-president Dana Walden, analyzed how hit show 24 would likely not have been made absent DVD revenues:

… the costs of producing a drama like 24 had become so prohibitive that it probably could not be made today without the DVD sales. Though the studio would not release exact figures, each of the series’ 120 episodes has cost just under $2.5 million to make, for a total of about $300 million. Licensing fees from the Fox Network are not believed to have exceeded $1.3 million an episode, for a total of no more than about $156 million. The rights to broadcast the series internationally have probably been sold for $1 million or more an episode, for a total of at least $120 million. All told, that revenue—about $276 million—has not been sufficient to eliminate the deficit and provide a profit. DVD sales, however, have.

“The DVD opportunity on this series has enabled us to produce the show that is on the air,” Ms. Walden said.23

This interdependency is the reason that the decline in certain sectors, such as the DVD market, has such a ripple effect. If DVD revenues materially decline (as they have), and revenues from new access points (e.g., downloads, VOD, and subscription rentals) are less than substitutional for the drops in the markets previously essential for overall financing, then how is expensive-to-produce premium product to be funded? This is the question of the day, and why the economic interplay of Ulin’s Rule can paint a frightening picture. This continuum also lies at the heart of the fight against piracy; while some fight against strengthening rules and enforcement, conjuring up the spectre of a regulated Web undermining free speech and access, the flip side is that if piracy goes unchecked and consumers can gain access to shows for free that are, in fact, supposed to be paid for, then the financing walls buttressing production come down and the quality of content tumbles with them. I know almost no TV or film executive that would disagree with this analysis, which is why it becomes all the more frustrating for studios and networks when laws designed, at their root, to address this problem are thwarted because of political movements grounded in free expression. The sad fact is that the same media executives believe fiercely in the same free expression, but somehow the message has become distorted and those that are actually allies have failed at cogently expressing common ground and outlining appropriate boundaries (see also discussion in Chapter 2).

Cable’s Advantage and Move into Original Programming

The risk profile of a series is directly proportional to the number of likely revenue sources for recoupment. As discussed in Chapter 3, cable networks can theoretically take greater risks than the broadcast networks because they have a dual-revenue stream from cable subscriber fees and advertising. The cable fees are guaranteed, and create a production funding pool insulating a particular series from the direct impact of advertising revenue; the subscriber fees are tied to the overall network and brand, such that a hit series can help drive brand value, but a one-off failure will not change the underlying economics (other than, of course, the impact on advertising for that show). This is one reason that cable networks are starting to offer more and more original programming: a hit or group of hits can help increase the brand value of the network and differentiate it to a greater extent than reruns. Accordingly, a series on a cable network can now draw from: (1) advertising dollars; (2) an allocation from cable subscriber fees paid to the network overall; (3) DVD revenues from box sets of seasons; and (4) emerging revenue streams, such as OTT rentals, subscription VOD, and EST downloads, to a growing array of tablets and other portable devices. A network series benefits from all of these sources except for the cable subscriber fees; however, that element alone can be so significant that the cable network can afford to take different risks and accept a lower audience rating.

The success of original cable series, as opposed to original series in syndication (e.g., Star Trek) has recently created an almost renaissance of original programming. The ability for non-networks to produce hit original series was proven by HBO, with hits such as Sex and the City and The Sopranos. Soon, non-pay channels realized they could enter the market as well, and the following is a snapshot of a few of the shows evidencing the trend of cable networks to develop their own franchises (of course, this had long been the trend with kids’ channels such as Nickelodeon with Jimmy Neutron, etc.):

■ USA: Psych, Burn Notice, Suits, White Collar

■ TNT: The Closer, Leverage, Franklin & Bash

■ F/X: Sons Of Anarchy, It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, Rescue Me

■ AMC: Mad Men, Breaking Bad, The Walking Dead

■ Syfy: Ghost Hunters, Eureka

■ Lifetime: Army Wives, The Client List

■ A&E: Dog the Bounty Hunter, Storage Wars

■ Disney Channel: Hannah Montana, Good Luck Charlie

In some cases, the show’s ratings have been extremely competitive, with TNT’s The Closer scoring network primetime-like numbers in a few instances (especially with season premieres). From dabbling, cable networks started to gain confidence in their ability to launch original series and began to leverage two inherent competitive advantages. First, cable stations could counter-program and start seasons in periods when the networks showed reruns. USA and TNT, for example, routinely air new episodes of series in the summer, enticing viewers who preferred new episodes to network reruns or replacements. Second, because cable stations program a full day, as opposed to a network that has limited primetime hours and must share promotional time with affiliates, the cable networks can cross-promote new shows literally nonstop; further, because they may only have a couple of original series, the promotion can reach channel saturation, optimizing marketing support to help shows break through the clutter. Accordingly, the cable networks tend to program their originals in sequence, rather than as a lineup, thereby maximizing promotion and always having something new (e.g., F/X will plug its fall original during its summer original series).

The issue now may become whether the market can absorb all these shows. As the market has matured, it may be, as Variety noted, that everyone needs to run faster just to stay in place:

The one-time vast wasteland of cable networks filled with repeats and wrestling has been replaced by a world in which even networks as small as Sundance Channel are producing quality first-run fare. No longer a band of misfits, basic cable’s top nets are spending more money on original fare and making more noise with marketing—yet they aren’t seeing their numbers grow. They’re having to do more just to maintain the status quo.24

A Golden Age for TV?

The strength of quality content, however, has somewhat disproven this flattening hypothesis, as there are significant examples of cable shows lifting the entire network. Mad Men on AMC, basic cable’s only winner of the Emmy for Outstanding Drama Series (not once, but four consecutive years starting in 2008) is a good example. Prior to launching hit originals, including Breaking Bad, The Walking Dead, and Mad Men, AMC was primarily known for older films and reruns, product that dovetailed with its original name (American Movie Classics). Leveraging cult followings, the network has been able to increase its cable licensing fees significantly (see Chapter 3 discussion of cable financing), with the New York Times estimating that AMC charges MSOs, like Comcast and DirectTV, upwards of $0.40 per month per subscriber—with national carriage and 80 million subscribers, that translates into $30 million per month for license fees, a sum that could not be commanded without viewers clamouring to see these select hits.25

The net result of more money to produce quality shows begetting more quality shows, while feeling a bit like a bubble, has in fact proven to be a virtuous cycle, lifting the quality bar to a point where many feel there is an unexpected renaissance in TV. Despite the competition from new digital and online sources (see also Chapter 7), the New York Times article “The Mad Men Economic Miracle” described this as television’s “golden age” and waxed on that: “Networks have effectively entered into a quality war. Basic-cable channels have to broadcast shows that are so good that audiences will go nuts when denied them. Pay TV channels, which kick-started this economic model, are compelled to make shows that are even better. And somehow, they all seem to be making insane amounts of money.”26

While all this is true, the digital competitive forces are lurking, and cable companies are well aware that cable bills have become extremely pricey and that they cannot simply keep raising rates (which is the only way to fund demands for increased subscriber fees, which are in turn commanded by cable channels succeeding with evermore original fare). Not only does cable have to fight cord-cutting by a new generation used to online access without forking out for cable bills, and expanding digital piracy of in-demand shows, but now the online companies are themselves getting in on the original content bandwagon. The production of original content by the online leaders that are aggregating content in the over-the-top space is a direct threat to cable, and exacerbates traditional media players’ fears of their digital competitors. Chapter 7 discusses how services ranging from YouTube to Amazon, Hulu, and Netflix are moving into online originals; among a variety of impacts, this new range of programming, including from some of the services themselves that are starting to look like an aggregator of cable channels, will be competing both for viewers and advertisers, putting pressure on cable that the industry has never before faced. The foregoing quoted New York Times article, in talking about AMC and how cable channels spin cliffhangers from their original series into gold, mused that while Charles Dickens had to sell the next chapter in books (that were published in a serialized form), no one has managed to monetize cliffhangers like TV (and cable TV); the article could, though, have as aptly quoted from Dickens that for TV, today it is truly the best of times and worst of times.

Upfront Markets, Mechanics of Advertising Sales, and Ratings

Advertising is the lifeblood of free television, and networks essentially lease portions of their airtime to advertisers, charging rent based on ratings. Much like any other rental market, rates can be based on long-or short-term rates, with discounts applied to prepayment or longer-term security scenarios. To grasp the mechanics of the television advertising landscape, imagine you owned an apartment building where certain views commanded premium pricing (exchanging the notion of view for viewership), discounts were applied to someone leasing bulk space, such as an entire floor, and each individual unit in the building was a unique property that commanded its own rental rate (yet still had some rational relationship to all the other units rented). In this analogy, the TV upfront markets would be akin to long-term rentals, the scatter market would equate to monthly or weekly rentals, and ratings would be the cost-per-square-foot barometer for setting the rental rates.

Upfront Markets

There are a couple of times a year when networks pitch their new season lineups to advertisers, trying to secure commitments for shows before broadcasts. This obviously secures capital/commitments to underwrite production costs, the annual ritual of which has come to be known as the upfront markets.

The mechanism of the upfront markets is relatively straightforward. Broadcasters auction off their commercial space, referred to as “inventory,” and receive guaranteed payments for the commercial space/spots. The buyers of spots obviously secure key placement for their products, as the upfront markets cover large commitments over long periods of time. Companies with a steady stream of advertising needs, such as auto companies or large packaged goods companies, will secure a range of spots that will then be allocated to specific products at a later date. Those companies buying large inventory and later allocating to clients tend to have products that need continuous marketing, and therefore do not need to have the first spot on NCIS on the week of November X. For this flexibility, they buy in volume and gain both the benefit of guaranteed delivery as well as a certain discount.