Market Opportunity and Segmentation

The Diverse Role of Studios and Networks

|

More content from this chapter is available at www.focalpress.com/9780240824239 |

This book provides an overview of how the business side of the television and motion picture industry works. By the end of the text, readers will gain a practical understanding of how a film, television, or video project moves from concept to making money. Stars make the headlines, but marketing and distribution convert content into cash. To explain how the system works, this book charts the path that entertainment content takes from development to financing to distribution, and attempts to demystify the submarkets through which a production is exhibited, sold, watched, rented, or otherwise consumed. In summary, this book explains the process by which a single idea turns into a unique piece of entertainment software capable of generating over a billion dollars and sustaining cash flow over decades. I will also attempt to put into context the growing array of Internet and other new media opportunities that are altering how we watch content and blurring the lines of how we define categories of media. Since the publication of my first edition, the introduction and mass adoption of tablets, along with the emergence of apps, has accelerated the trend toward on-the-go and on-demand access to the point where digital distribution systems have moved from being labeled as disruptive to representing the future of the market. What I will explore in this book, and what all media companies continue to struggle with, is why it is so challenging to make as much (if not more) money through these new avenues as traditional outlets.

With the potential of generating great wealth by creating and distributing content also comes great risk, and motion picture studios today can be seen as venture capitalists managing a specialized portfolio. In contrast to traditional venture capitalist investments, though, film investors risk capital on a product whose initial value is rooted in subjective judgment. Valuing creativity is tough enough, but investing in a film or TV show often asks people to judge a work before they can see it—a step back from the famous pornography standard “I know it when I see it.” Bets are accordingly hedged by vesting vast financial responsibility over productions in people who have developed successful creative track records. Focusing too much attention, though, on creative judgment as opposed to marketing and financial acumen risks failure, and managers who can balance competing creative and business agendas often become the corporate stars. Analysts seeking trends may promote “content is king,” but in the trenches success tends to be linked with marrying creative and sales skills.

As a result of this mix, there is no defined career path to breaking into the business or rising to success within it. Unlike attending law school and rising to partner, or business school and aspiring to investment banking, leaders in the film and TV world are an eclectic group hailing from legal, finance, producing, directing, marketing, and talent management backgrounds. Without a clear educational starting point or defined career path, how do these leaders and entrepreneurs learn the “business”?

Beyond what I hope will be a “we wish we’d had this book” reply, the simplest answer is that many executives learn by some form of apprenticeship. As an alternative to starting in the mailroom, which will always remain both a legendary and real option for breaking into the entertainment business, this book will equip readers with a basic understanding of the economics and business issues that affect virtually every TV show and film. Behind every program or movie is a multi-year tale involving passion, risk, millions of dollars, and hundreds of people. In fact, every project is akin to an entrepreneurial venture where a business plan (concept) is sold, financing is raised, a product is made and tested (production), and a final product is released.

While this sounds simple enough, the potential of overnight wealth, a culture of stars, and the power of studios and networks serve to throw up barriers to entry that segment the industry and make the entertainment production and distribution chain unique. The emergence of online and digital distribution is changing the equation, enabling cheaper, faster production and seemingly ubiquitous and simultaneous access to content; whether sustainable business models evolve to generate the bulk of revenues from these new platforms or these outlets simply serve as supplementary access points for content remains the question of the day.

What is certain, however, is that to understand these new avenues one has to understand the historical landscape. Traditional media (film/TV/video) still accounts for over 90 percent of all media revenues, and the success of online/digital ventures will be tied to how opportunities relate to existing revenue streams. The exploitation of media is a symbiotic process, where success is achieved by choreographing distribution across time and distribution outlets to maximize an ultimate bottom line. Media conglomerates have developed a fine-tuned system mixing free and paid-for access (TV versus theaters), varying price points (DVD sales and rentals, pay TV, video-on-demand), and windows driving repeat consumption—a system that will generate far more money (and therefore sustain higher budgets) than an ad hoc watch-for-free-everywhere-now structure. It is because the Internet offers the chance to dramatically broaden exposure, lower costs, and target finely sliced demographics that the two systems are both attractive and struggling to merge in a way that ensures expansion rather than contraction of the pie.

Market Opportunity and Segmenting the Market

A reference to the “film and TV market” is a bit of a misnomer, because these catch-all categories are actually an aggregation of many specialty markets, each with its nuances and particular market challenges. The rest of the chapters of this book detail exploitation patterns common across product categories, such as how a property is distributed into standard and emerging channels, while this chapter first outlines the range of primary markets and niche businesses. I will also try to highlight differing risk factors and financials that are explored in greater detail later in the book, but here I want to focus on the diversity of the market and how it can be segmented. In fact, the simple process of segmentation illustrates the diversity of the business and how studios can be defined as an almost mutual fund-like aggregation of related businesses with differing investment and risk profiles. It is because of this range of activities and the way a studio can be characterized that business opportunities tend to be “silo-specific”; a successful business plan in the entertainment industry is likely to focus on limited or niche risk profiles and financials. Except for the launch of DreamWorks (which ultimately retrenched to primarily focus on film production), it is rare for any entity to try to tackle the overall market from scratch.

Defining Studios by Their Distribution Infrastructure

There are a finite number of major studios (i.e., Sony, Disney, Paramount, Universal, Warner Bros., Fox, and MGM), and the greatest power that the studio brings to a film is not producing. Rather, studios are financing and distribution machines that bankroll production and then dominate the distribution channels to market and release the films they finance.

Accordingly, the most defining element of a studio is its distribution arm—this is how studios make most of their revenue, and is the unique facet that distinguishes a “studio” from a studio look-alike. Sometimes a company, such as Lionsgate or Miramax in its original iteration (when run independently by Bob and Harvey Weinstein), will have enough scale that it is referred to as a “mini-major.” This somewhat fluid category generally refers to a company that is independent, can offer broad distribution, and consistently produces and releases a range of product; again, though, what largely distinguishes a mini-major from simply being a large production company is its distribution capacity. Any company, studios included, can arrange financing: there are plenty of people that want to invest in movies. In this regard, the film business is no different than any other business. Is the production bank-financed, risk/VC-financed, or funded by private individuals? (See Chapter 3 for a discussion of production financing.)

What is different with studios is that they will not invest (generally) in a film without obtaining and exercising distribution rights. This is because they are, first and foremost, marketing and distribution organizations, not banks. Sure, they buy properties, hire stars, and finance the films they elect to make; however, to some extent this can be viewed as a pretext to controlling which properties they distribute and own (or at least control). If the project looks like a hit, it is captive, and the studio, through its exclusive control of the distribution chain, can maximize the economic potential of the property. If the property fails to meet creative expectations, however, the studio has options, from writing it off and not releasing the property, to selling off all or part of the rights as a hedge, to rolling the dice with a variety of release strategies.

So, beyond money, which anyone can bring, and creative production, which an independent can bring, what is it about distribution that separates studios?

What Does Distribution Really Mean?

Distribution in Hollywood terms is akin to sales; however, it is more complicated than a straightforward notion of sales, given the nature of intellectual property and the strategies executed to maximize value over the life of a single property. Intellectual property rights are infinitely divisible, and distributing a film or TV show is the art of maximizing consumption and corresponding revenues across exploitation options. Whereas marketing focuses on awareness and driving consumption, distribution focuses on making that consumption profitable. Additionally, distribution is also the art of creating opportunities to drive repeat consumption of the same product. This is managed by creating exclusive or otherwise distinct periods of viewing in the context of ensuring that the product is released and customized worldwide.

In contrast to a typical software product, the global sales of which are predicated on a particular release version (e.g., Windows 98), a film is released in multiple versions, formats, and consumer markets in each territory in the world.

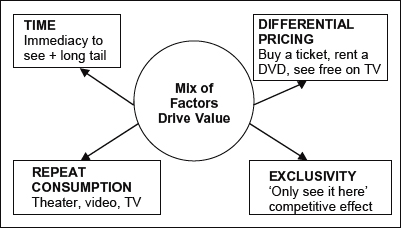

Figure 1.1 represents what I will call “Ulin’s Rule”: content value is optimized by exploiting the factors of time, repeat consumption (platforms), exclusivity, and differential pricing in a pattern taking into account external market conditions and the interplay of the factors among each other.

Figure 1.1 Ulin’s Rule: Four Drivers of Distribution Value

Launching content via online distribution presents monetization challenges because simultaneous, nonexclusive, flat-priced access does not allow the interplay of Ulin’s Rule factors: use of online platforms tend only to drive value by exploiting the time factor. To earn the same lifetime value on the Internet for a product that would otherwise flow through traditional markets not only must initial consumption expand to compensate for a decline caused by cutting out markets in the chain (or reduced because a driver such as exclusivity is removed), but also it must compensate for the cumulative effect of losing the matrix of drivers that have been honed to optimize long-term value. When thinking about Internet opportunities and different distribution platforms, keep in mind these elements and ask whether the new system is eliminating one or more of the factors: if the answer is yes, then there is likely a tug of war between the old media and new media platforms, with adoption slowed as executives struggle for a method of harmonizing the two that does not shrink the overall pie.

Importantly, the impact of eliminating one or more drivers does not change the value equation in a linear or pro-rata fashion. In the evolved ecosystem of exploiting windows, the legs work better together and the elimination of a driver has an uncertain, although inevitably negative, consequence on monetization.

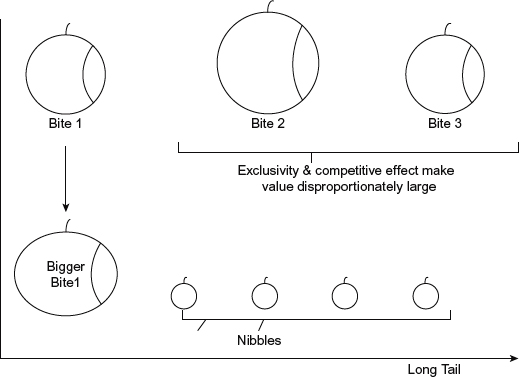

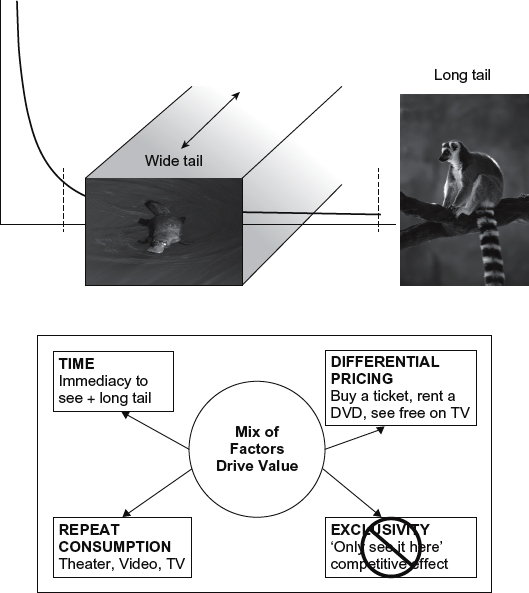

For example, as I argue in more detail in Chapter 7, a persistent video-on-demand (VOD) model is a natural outgrowth of enabling technology and the long-and-wide (everything-available-now) tail (Figure 1.2); if, as a further consequence, a form of persistent VOD monetization undermines exclusivity or eliminates the concept of time segmentation (such that content is always available), then ultimate content value can be severely undercut (Figure 1.3). In such a scenario, the platforms creating gating access to content may bolster returns, but the individual content provider is unlikely to ever reach its prior equilibrium of value. This trend is currently hidden by the gold rush of new services vying for content to secure programming in the short term; however, value is being maintained by either traditional exclusivity or a form of quasi-exclusivity by the club of new platform/service leaders, and if exclusivity starts to truly evaporate and persistent VOD takes hold, then value will fall below the prior benchmarks. This is necessarily the case when the second and third bites at the apple (e.g., video revenues), which have often been equal to or greater than the first bite, are no longer viable (or as viable). It is a product of managed window systems optimizing the mix of value drivers—not in a persistent VOD model—that such subsequent bites can be bigger.

Figure 1.2 The Long Tail

Although the realization of the long tail has been ballyhooed as good for content, I am arguing quite the contrary in terms of content value. A consumption shift to infinite shelf space (what I will dub the wide tail, or the online platypus) and infinite shelf life (the long tail) does not automatically enhance content value. In fact, the result is quite the contrary. Despite easier, better, broader access to all content, if that access is achieved via elimination of a driver, then Ulin’s Rule means that lifetime value for a content provider will actually diminish.

As earlier noted, the one counterweight to this decline is an upfront expansion of consumption, but it is unlikely that more people watching or buying at launch can compensate for reductions suffered in traditional downstream windows. Additionally, to those arguing for the elimination of windows and forecasting that a fully open system would engender more people consuming earlier—unshackled from the barriers thrown up by content distributors to window and therefore withhold content per the consumer’s creed that programming should be freely available whenever you want it, wherever you want it, however you want it—I need simply to point out that media consumption today is already heavily front-loaded. As discussed in Chapter 9 regarding marketing (and elsewhere throughout the book, including Chapter 3 regarding experience goods, and Chapters 4–6 covering the theatrical, video, and TV markets), few, if any, other businesses spend so much money in an effort to launch brands overnight. The media business, in part as a strategy to combat piracy and in part to propel a number of the value drivers, including immediacy of viewing/consumption, spends inordinate amounts of money and energy exciting consumers to stampede the box office and other downstream launches; when all possible tactics are already utilized, and the vast majority of box office and video revenues come within the first two weeks of launch, it is quite legitimate to ask whether there is any additional consumption that can be driven upfront, let alone whether the net would be so much wider that it could substitute for shrinking viewership in later windows. (Note: while TV is not an exact parallel, given the need to sustain consumption over episodes, similar efforts are made to launch series to as big an audience as possible, with the goal of creating a significant enough base to leverage for continued viability.) (See also discussion of binge viewing in Chapter 7).

Figure 1.3 Persistent VOD: a Natural Outgrowth of the Platypus and Long-tail Effect, coupled with Elimination of a Value Drive, Reduces Content Value

Again, the window system is inherently an optimized system for lifetime management. With online, though, the tail is wider (my online platypus effect), but not necessarily longer for product most want to see: video enables greater depth of copy than theatrical, pay TV fills up airtime with hits and misses, and cable has long exploited viewing of niche product still driving demand but not worthy of premium placement (e.g., Nick at Nite). The challenge is that it is counterintuitive to admit that value can go down by providing more content with easier access.

Simply, while our platypus coupled with a long tail may posit infinite shelf space and infinite content, in the real world there are not infinite buyers and infinite advertisers to match this availability. (Note: This effect is often depicted in the context of monetizing Web pages, where websites similarly trend toward infinite; see also Figure 6.3 on page 308 regarding this effect.) Moreover, because new content is generally more valuable (sorry, most long-tail business model proponents), more long-tail content, if niche, likely means that it is fighting for already marginal dollars—the wide tail then only complicates matters by adding infinite competition to an already marginalized tail. It is because of all these factors that Ulin’s Rule and the maximization of distribution value is more complex in practice than the simple diagrams above—throughout this book I will attempt to dissect the many moving parts and how each key content revenue opportunity contributes to the whole and is adapting to new digital permutations and challenges.

Range of Activities—Distribution Encompasses Many Markets

To accomplish the feat of releasing a single property in multiple versions and formats to a variety of consumer markets, a huge infrastructure is needed to manage and customize the property for global release. The following is a sample listing of release markets, versions, and formats.

Specialized Markets Where a Film is Seen:

■ video and DVD/Blu-ray

■ pay television

■ pay-per-view television/video-on-demand (PPV/VOD)

■ free and cable television

■ hotel/motel

■ airlines

■ non-theatrical (e.g., colleges, cruise ships)

■ Internet/portable devices/tablets

Formats:

■ film prints (35 mm, 70 mm, 16 mm)

■ digital masters for D-cinema

■ videocassette (though disappearing rapidly)

■ DVD/Blu-ray

■ formatted (and often edited) for TV broadcast (video master) and

■ compressed for Internet/download/portable devices

Versions:

■ original theatrical release

■ extended or special versions for video/DVD (e.g., director’s cut)

■ widescreen versus pan-and-scan aspect ratio

■ accompanied by value-added material (commentary, deleted scenes, trailers)

The need for different markets, formats, and even versions creates a complex matrix for delivery of elements. Moreover, as technology affords more viewing platforms, the combinations can grow by a multiple; for example, because DVD was additive to video (at least initially), the product SKUs increased by a factor of this doubling of the distribution channel times the number of versions released. Take this formula and compound it by all major territories in the world, and the complications of supplying consumer demand involve complex logistics.

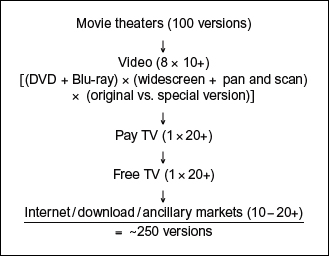

The following illustrates this point. Assume a studio or producer has a family genre movie, such as Avatar or Spider-Man, that will be released “wide” in all traditional release channels in all major markets in the world. How many different versions of the film do you think need to be created, marketed, sold, and delivered? In my first edition, I described how the number can quite easily equal 150 versions across the range of release platforms, and possibly even more. That statement was premised on an assumption that the movie was initially released in theaters, in at least 20 major markets around the world, requiring upwards of 20 different film-print versions. The growth of digital cinema, though (see further description in Chapter 4), has dramatically increased the number of versions. The complexity is a function of multiple competing digital cinema systems and the growth of 3D, where there is a technical challenge in standardizing lighting levels; the upshot is the requirement of color timing to harmonize the appearance across different systems and, to some extent, managing the logistics of customizing per theater to assure consistent exhibition. For the DreamWorks animation film How to Train Your Dragon, the Hollywood Reporter estimated that there were 2,342 3D digital files (across a myriad of 3D projection systems, including Dolby, Master Image, RealD, and Xpand), and quoted Jeffrey Katzenberg as noting that “We now have a higher degree of complexity needed to put the right version of the movie in the right system in each theater.”1 As systems inevitably consolidate and converge over time, this matix of prints will shrink, but for the time being, with films such as Avatar released in more than 90 international versions (47 languages, and specialized versions required across digital 2D screens, 3D versions, and IMAX venues), my prior total of 150 different versions could conceivably be reached solely from theatrical prints.2 Figure 1.4 below assumes:

■ the movie is initially released in theaters, in at least 35 markets around the world

■ the movie is released worldwide in the home-video market on DVD and VHS, and that consumers are offered a range of formats, such as a letterbox version (a “widescreen” version that leaves black on the top and bottom of the screen) and a “pan-and-scan” version that is reformatted from the theatrical aspect ratio to fill up a traditional square television screen (note: VHS releases and pan-and-scan are largely phased out, but the analogy remains, as for example, there will be Blu-ray and traditional DVD SKUs)

■ the film is released into major pay TV markets worldwide (channels may have different specs)

■ the film is edited for broadcast on major network TV channels

■ the property is compressed for Internet/download and streaming viewing

■ miscellaneous other masters, with different specs, are needed for ancillary markets such as airlines

Figure 1.4 Volume and complexity of Release Versions

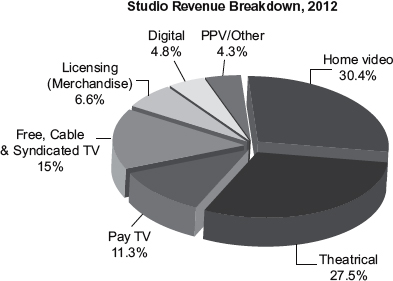

Relative Size of Distribution Revenue Streams

In the following chapters, I will discuss each of the key sub-markets in detail, but it is helpful to put the different revenue streams in perspective. Figure 1.5 illustrates the major revenue streams that have collectively generated upwards of $50 billion in each of the last several years.

Figure 1.5 Motion Picture Distributor Revenue Streams

© 2012 SNL Kagan, a division of SNL Financial LC, analysis of video and movie industry data and estimates. All rights reserved. (Diagram created by author from data provided).

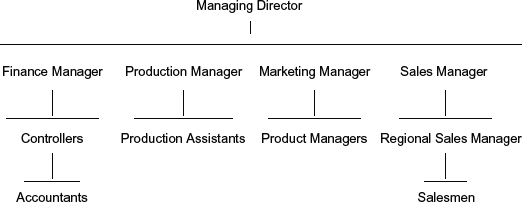

Not every new format or element above adds significant new complexity, but to manage just the theatrical distribution chain, which represents only a portion of the distribution channels, requires significant overhead. Within each of the primary divisions (theatrical, pay TV, free TV, video), there are several key functions that need to be staffed. (Note: Digital/online can be structured as an independent division or coordinated and absorbed among divisions, such as when video also manages electronic sell-through sales.) Typically, there are dedicated sales, marketing, and finance staff plus general management; to the extent there is a formula, every subsidiary office in an overseas territory would replicate this general structure.

To extrapolate cost, let us assume 10 people per office with an average salary of $100,000, and that salary costs represent approximately 60 percent of the office’s budget, with SG&A expenses accounting for the other 40 percent. That would represent a budget of approximately $1.7 million per office. Assuming 12 offices, this represents $20 million of overhead per year for a film or video division; the United States remains the largest and most fiercely competitive market in the world, with overhead costs (including international oversight) that can represent a significant portion of the worldwide overhead numbers.

Arguably, the foregoing is a conservative snapshot, for upwards of 1,000 people can be employed worldwide at a major studio across the divisions comprising the distribution chain. To illustrate the size, simply take a key individual territory as an example. A major operation in France could easily have 50 or more people, depending on structure and product flow, with an organizational infrastructure as seen in Figure 1.6 (excluding personal assistants/administrative support).

Figure 1.6

Usually, the largest number of people is in the sales area, and a geographically dispersed area with hundreds or even thousands of individual accounts to cover could comprise half of the overall headcount. (Note: in some cases, there could also be dedicated legal, although legal and business affairs tend to operate at headquarters.)

The overhead required to run the distribution apparatus cannot be justified without a sufficient quantity of product to market and sell. This relationship is fairly straightforward: the more titles released, the greater the revenue, and the easier to amortize the cost of the fixed overhead. Stated simply, if there were $50 million in distribution overhead, an independent releasing five films per year would need to amortize $10 million per film, whereas a larger studio releasing 25 pictures would need to recoup only $2 million per picture in overhead costs.

Studio distribution is the organization and function that matches the content pipeline with the challenge of delivering that content to every consumer on the planet—multiple times.

Complexity + Overhead + Pipeline = Studio Distribution

The above infrastructure and needs is the underbelly of the studio system, and what studios do better than anyone else is market and distribute film product to every nook and cranny of the world.

The other piece of the equation is control, which requires a more hands-on distribution approach than would otherwise be acceptable in an OEM or purely licensed world. Control can be viewed in terms of a negative or positive perspective. The need for control in a negative sense exists as a watchdog feature, providing security to producers and investors and others associated with the project, and assuring that the project is looked after properly. Control in a positive sense means that proper focus can be brought to distribution, thereby increasing the revenue potential on a particular project. Arguably, in the Hollywood context, these can be of equal importance.

Negative Control

Films are very individual, with stars, producers, and directors so vested in the development, production, and outcome that they have enormous influence over detailed elements of release and distribution. When travel was less ubiquitous than it is today, and revenues from international markets were a nice sprinkling on top of United States grosses, attention may not have been as significant; however, when a top star or director is likely to hear about (or even see) what has happened to his or her film in Germany or Japan, they will generally want the same rules applied in local markets as in Hollywood and New York. The only way to police this is on-the-ground control, making it less likely to cede supervisory control in major markets to mere licensees. How can the studio boss look his or her most important supplier in the face and pledge, “we’ll take care of you” if he has passed the baton locally?

Executives will not risk their careers on “he’ll never know about it,” and the danger of discovering noncompliance has ratcheted up with every improvement in communications technology. A couple of years ago, I speculated that if an advertisement that required Tom Hanks’s approval was improperly handled in Spain, a competitor could take a picture of it on his cell phone and transmit it to his agent in Los Angeles over a wireless Internet connection instantly. Now, with the advent of Twitter and other blogging/microblogging sites, the risk is even greater, for an issue or incident can go viral almost instantly, effectively bypassing damage-control safeguards. If you were counting on Mr. Hanks for your next picture, or if this represented a breach of your contract for a current picture in release, would you risk it?

Positive Control

By positive control, I simply mean that focus will usually lead to incremental revenue. Sub-distribution or agency relationships, by their nature, yield control to third parties, and studios tend to have direct offices handling distribution in their major markets. Only with this level of oversight can a distribution organization push its agenda and maneuver against its competitors, who are invariably releasing titles of their own at the same time and to the same customers. This direct supplier–customer relationship is what studios offer to their clients—a global matrix of relationships and focus that an independent without the same level of continuous product flow cannot support.

The Independent’s Dilemma

An independent may not care as much about some or all of these issues, for it may have less entrenched relationships or be more willing, by its very nature, to take on certain risks. It still, though, has to release its product via all the key distribution channels (e.g., theatrical, TV, video) and into as many territories as possible around the world. To raise money, it may make strategic sense to license rights (often tied to a guarantee), which in turn usually has the consequence of ceding an element of control, as well as some potential upside; to the independent, though, securing an advance guarantee or accepting that less direct control may forfeit revenues at the margin may greatly outweigh the burden of carrying the extra overhead. In essence, they can beat over 70 percent of the system, but they cannot match the pure strength and reach of the studio distribution infrastructure. And to many people, especially on big movies with powerful producers and directors behind them, a pitch of “almost as good” simply is not good enough.

The pressure to fill a pipeline and bring down per-title releasing costs while guaranteeing the broadest possible release is great, and even defining of what makes a studio. Despite the fact, however, that costs come down in a linear progression relative to titles released, the total overhead is still a very large number; such a large number, in fact, that it has frequently led to the formation of joint ventures. A joint venture may only need an incremental amount of extra overhead, if any, while perhaps doubling or tripling the throughput of titles. In the above studio case, a joint venture could easily increase the title flow from 25 to 60, bringing down the per-recoupment number in the above scenario to under $1 million per title to cover the overhead.

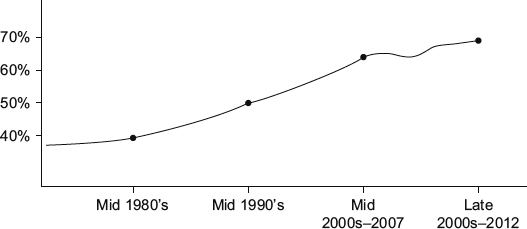

Studio joint ventures grew in the 1980s with the globalization of the business. The number of titles a studio released fell within a relatively static range, and even a significant percentage increase in product still meant a finite number of major films (e.g., 20 or 30). What changed dramatically was the importance of the international markets. In the early 1980s, the international box office as a percentage of the worldwide box office was in the 40 percent range, then grew to over a 50 percent share by the mid 1990s, by the mid 2000s had grown to more than 60 percent,3 and by 2010 started to approach 70 percent (e.g., 68 percent in 2011; see Figure 1.7 and also Table 4.1 in Chapter 4). (Note: In 2010, foreign sales accounted for roughly 70 percent of total receipts, both for industry and for the movie Avatar.4) The splits, of course, are picture-dependent and, in extreme cases, can have an international share close to 80 percent, with Universal’s Battleship having an international share of nearly 79 percent, and Fox’s Life of Pi around 80 percent.5 But the overall trend is clear, especially for box office hits with international stars and franchise recognition.6 With the emergence of China as a major theatrical market (see Chapter 4), this trend of international box office dominating global box office is poised to continue. Moreover, in instances, films are now starting to be released first overseas, a trend that was anathema just a few years ago. In the spring of 2012 (leading off the summer season), Disney debuted its hit The Avengers first in key international territories, and Universal followed suit, launching Battleship overseas. In an unprecedented step, and telling trend, the U.S. was the last major theatrical territory in which Battleship was released.7

Figure 1.7 International Box Office as a Percent of Worldwide Box Office

Data reproduced by permission of SNL Kagan, a division of SNL Financial LC, estimates. All rights reserved.

When individual territories outside the United States started to represent the potential, and then the actual, return of tens of millions of dollars, the studios needed to build an infrastructure to manage and maximize the release of their products abroad. Moreover, this matured market by market. First, the growth of the international theatrical market warranted the expansion. Shortly thereafter, with the explosive growth of the videocassette market in the 1980s and 1990s, including the 1990s expansion of major United States retailers such as Blockbuster to international markets, studios needed to mirror theatrical expansion on the video side. Distribution of videocassettes (now DVDs and Blu-rays) and of movies into theaters utilizes the same underlying product and target consumers, but the similarities stop there; the differences of marketing a live event in theaters versus manufacturing a consumer product required different manufacturing, delivery, and marketing, and with it a different management infrastructure.

Three studios joined together to form United International Pictures, better known in the industry by its abbreviation UIP. Headquartered in London, UIP was historically a joint venture among Paramount Pictures, Universal Pictures, and MGM (MGM later dropped out, but the volume of titles remained high as DreamWorks titles were put through the venture). The three parties shared common overhead in the categories described above: general management, finance, marketing, sales, and legal. Additional efficiencies were gained by sharing office space and general sales and administrative budget cost lines.

What was not shared is perhaps more interesting—the parties shared costs, but did not share revenues. A cost-sharing joint venture is a peculiar instrument of fierce competitors in the film community. Natural adversaries came together for two common goals: protection of intellectual property and the need to establish sales and marketing beachheads around the globe for as little overhead as possible. Both goals could be completely fulfilled without sharing revenues on a per-product or aggregate basis; perhaps more importantly, the structure of the business likely would not have permitted the sharing of revenues even if this was a common goal. Because each film has many other parties tied to it, with complicated equity, rights, and financial participation structures, it is unlikely that all the parties who would need to approve the sharing of such revenues would ultimately agree to do so.

Why, for example, would Steven Spielberg and Universal all agree to share revenues on its film Jurassic Park with Paramount or MGM? Similarly, why would Paramount Pictures and Tom Cruise want to share revenues on Mission: Impossible with Universal? The simple answer is they would not, and they do not. Every one of these parties, however, has a vested interest in the films released under a structure that: (1) minimizes costs and therefore returns the greatest cash flow; (2) protects the underlying intellectual property and minimizes forces such as piracy that undermine the ability to sell the property and generate cash; and (3) maximizes the sales opportunities.

Once this formula is established, it is relatively easy to replicate for other distribution channels. UIP, for example, spun off a separate division for pay TV (UIP Pay TV), a market that exploded in the early 1990s. The same theatrical partners joined forces to lower overhead and distribute product into established and emerging pay TV markets worldwide.

Additionally, two of these partners, Paramount and Universal, teamed up for videocassette distribution and formed CIC Video (where I once worked, based in UIP House in London). CIC, similar to UIP and UIP Pay TV, set up branch operations throughout the world headquartered in the UK. Table 1.1 is a representative chart of countries served by direct subsidiary offices.

In addition to direct offices, the venture would service licensees in countless other territories. These are examples of territories typically managed by studios as licensee markets: Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Czech Republic, Ecuador, Finland, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Indonesia, Israel, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, Uruguay, and Venezuela. (Note: This is not an exhaustive list.) Whether it makes sense to operate a subsidiary office or even to license product into a territory at all depends on factors including market maturity, economic conditions, size of the market, and the status of piracy/intellectual property enforcement. Many of the largest developing markets, which historically have been licensee territories throughout most of the span of the era of joint ventures, including Russia, China, and India, are being transitioned by studios into direct operations. Russia serves as a prime example, as rapid economic growth propelled the theatrical market from insignificant to among the top 10 worldwide markets in just a few years.

Table 1.1 Countries Served by Direct Subsidiary Offices/Territory

Australia |

Malaysia |

Brazil |

Mexico |

Denmark |

New Zealand |

France |

Norway |

Germany |

South Africa |

Holland/The Netherlands |

South Korea |

Hong Kong |

Spain |

Italy |

Sweden |

Japan |

United Kingdom |

UIP and CIC, although among the longest lasting and most prominent joint ventures (UIP was formed in 1981), are simply examples, and many other companies similarly joined forces in distribution (e.g., CBS and Fox formed CBS/FOX Video, partnering to distribute product on videocassette worldwide).

Demise of Historic Joint Ventures

None of UIP, CIC, UIP Pay TV, or CBS/FOX Video exists today in their grand joint-venture forms. First, UIP Pay TV was disbanded in the mid 1990s, then the video venture CIC was largely shuttered by 2000, and finally UIP’s theatrical breakup/reorganization was announced in 2005 and implemented in 2006 (though the partners still distribute via the venture in limited territories). Why did this happen?

The answer is rooted partly in economics and partly in ego. The economic justification in several instances was less compelling than when the ventures were convenient cost-sharing vehicles enabling market entry and boosting clout with product supply. In the case of pay TV, for example, the overhead necessary to run an organization was nominal when compared to a theatrical or video division. Most countries only had one or two major pay TV broadcasters; accordingly, the client base worldwide was well under 50, and the number of significant clients was under 20.

This lower overhead base, coupled with growing pay TV revenues, made the decision relatively easy. Additionally, given the limited stations/competition and the desire to own part of the broadcasting base, the studios started opportunistically launching joint or wholly owned local pay TV networks. Over time, services such as Showtime in Australia or LAP TV in Latin America, both of which are owned by a consortium of studios, became a common business model. Fox was among the most aggressive studios, replicating its successful Sky model in the UK and owning or acquiring significant equity stakes in the largest number of pay TV services worldwide. The Fox family of global pay networks grew to include the following major services:

■ BSkyB—UK

■ Star—Asia (including Southeast Asia, India, Mideast, China/Hong Kong)

■ Sky Italia—Italy

■ LAP TV (partner interest in Latin American service)

■ Showtime—Australia (partner in PMP, pre-Foxtel interest)

The logic behind the breakups of CIC and UIP are a bit more complicated, and are seemingly grounded as much in politics as economics. In both instances, the companies called on thousands of clients, and the range of titles from multiple studios virtually ensured the entity of some of the strongest and most consistent product flow in the industry—a fact that is critical in a week in, week out business. A video retailer is more likely to accept better terms and take more units from one of its best suppliers, knowing that a blockbuster it is likely to want will always be just around the corner. This strength of product flow, however, also turned out to be a problem with local competition authorities.

UIP was forced to defend anticompetitive practices allegations for years, and formally opposed an investigation by the European Union Commission (Competition Authority) in Brussels that threatened sanctions and even the breakup of the venture. Some argue that the EU Commission’s claims were politically bolstered by member states with protectionist legislation and quotas for locally produced product. In the end, UIP was successful in its defense, but the company was always a political target and forced to be on guard. While CIC was not similarly subject to an EU Commission inquiry, as a sister company it was always conscious of the issues.

In addition to theoretical arguments regarding anticompetitive behavior given market leverage, these types of joint ventures were always in the spotlight for specific claims. One of the most active watchdogs has been the competition authority in Spain. In 2006, the studios were fined by the Spanish authorities on a theatrical claim. Variety reported: “In the biggest face-off in recent years between Hollywood and Spanish institutions, Spain’s antitrust authorities have slammed a €12 million ($15.3 million) fine on the sub-branches of Hollywood’s major studios in Spain for cartel price fixing and anticompetitive coordination of other commercial policies.”8 Cases such as this only make operators of a joint venture among studios all the more paranoid.

Competition concerns aside, these ventures always had the maverick studio boss looming over them, wary that his or her film was somehow disadvantaged by treatment of a competitive partner’s title. The defense to this type of attack is that there will always be a competitive film, and better it be in the family so the headquarters can work to maximize all product; at least in a venture it is theoretically easier to schedule releases and allocate resources so that one studio’s product is not directly against another partner’s product (although, in practice, pursuant to antitrust/competition rules studios cannot share release dates). Ultimately, no matter what argument is made, the concern comes down to focus: every studio wants its big title pushed at the expense of everything else, and this is hard (at least by perception) to achieve in a joint venture. As the markets matured, and the international theatrical and video markets continued to grow as a percentage of worldwide revenues, many studio heads wanted unfettered control and dedication for key territories.

Many have argued that the breakup of these ventures simply for dedication and control is economic folly. These joint ventures had been releasing major studio hits for decades without discriminating one over the other. In fact, they could not discriminate, for the partners were always wary of this, and any significant diverting of focus or resources to one partner versus another would not be tolerated. Moreover, focus/dedication would have to yield a return that recovered 100 percent of the overhead now borne by the studio that had been allocated to its partner(s) previously. In a 50/50 joint venture, that means recouping an equivalent of 100 percent more than it needed to previously (e.g., if $20 million in total overhead, the studio now needed to recoup the full $20 million rather than only $10 million), and in a partnership with three parties it was even worse. These are pure bottom-line sums, for direct picture costs were already allocated by title. It is for this reason that politics comes into the equation. Clearly not all product will have an uplift to cover the additional overhead costs, but by the same measure never again will an executive of Studio X be fearful that he or she left money on the table for a major release because resources were diverted to a competitor’s film.

Branding and Scale Needs: Online Giving Rise to a New Era of Joint Ventures?

Perhaps the Internet and new digital delivery systems are fostering a new era of joint ventures. Today, global reach need not be achieved in an iterative fashion by rolling out international subsidiaries; rather, given unprecedented online adoption rates (e.g., YouTube, Facebook), companies are competing in a kind of virtual land-grab and teaming up for services that offer instant scale.

As discussed in Chapter 7, NBC/Universal and Fox partnered in 2008 to launch Hulu; by combining the breadth of programming from these two networks/studios, the on-demand service was able to offer diversified, premium content on a scale to support a new distribution platform. (Note: The joint venture expanded in 2009 when ABC became a third partner.) Similarly, looking to innovate within the on-demand space, Paramount, MGM, and Lionsgate in 2008 (each looking for alternatives to their historical Pay TV output deals with Showtime) formed the joint venture Studio 3 Networks, branding its distribution service “Epix.” Epix, a hybrid premium television and video-on-demand service, bills itself as a “next-generation premium entertainment brand, video-on-demand and Internet service,” leveraging diversified content from its partners and providing multiplatform access to satisfy the new consumer who insists on viewing content anywhere, anytime.9 Both of these services followed the major studios’ initial foray into the online space, where MovieLink and CinemaNow were launched as joint ventures to download films, but for a variety of reasons never achieved hoped-for adoption levels (see Chapter 7).

Studios as Defined by Range of Product

Although I will continue to argue that the distribution capacity and capability of a studio in fact defines a studio, this is not the popular starting point. Most look at a studio as a “super producer,” with the financial muscle to create a large range of product. Given consolidation of most TV networks into vertically integrated groups, this range of product is further diversified by primary outlet (e.g., made for film, TV, online). Although I may refer in some of the examples below to only one category, such as film, the premise often holds across media types, which accentuates the distribution diversity under the broader media groups.

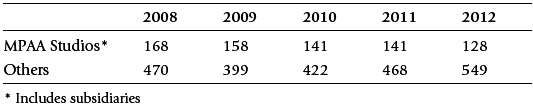

It is instructive to compare a studio to an independent on two basic grounds: quantity of product and average product budget. On these two statistics alone, it would be easy to segment studios. From a pure quantity standpoint, studios have the greatest volume of product. MPAA member companies collectively tend to release in the range of 150–200 new feature films per year, and while the total number of independent films released is usually more than double that number (approximately 400 per year, for a total of approximately 600 films per year released in the United States), the independent releases tend to be on a much smaller scale and capture only a sliver of the total box office receipts (even if, as of late, they are capturing more of the awards glory); moreover, no individual independent releases more than a handful of movies per year. (Note: A good example of a top independent, often releasing pictures gaining recognition at film festivals, is Samuel Goldwyn Films.) Table 1.2 evidences the consistency of the trend regarding number of films released per year.

Viewed from the standpoint of an independent producer, whose companies tend to be dedicated to the output of individuals (e.g., a producer or director), even the largest and longest tenured independents are limited to the number of films their key players can handle in a given period. New Regency, headed by Arnon Milchan, Imagine Entertainment, led by Brian Grazer and Ron Howard, and Working Title Films, run by Tim Bevan and Eric Fellner, are three of the largest and most consistently producing independents over approximately the last 20 years. New Regency has long been affiliated with Fox, while both Imagine and Working Title have distribution output deals with Universal. Table 1.3 lists samples of films over the last few years from each, as well as a couple of the films that catapulted each group to “producer stardom.”

Table 1.2 Number of Films Released Per Year in the U.S.10

Table 1.3 Examples Films Produced by Leading Independents

New Regency |

Imagine Entertainment |

Working Title |

Famous Films |

Famous Films |

Famous Films |

Mr. & Mrs. Smith |

Apollo 13 |

Four Weddings and a Funeral |

Pretty Woman |

A Beautiful Mind |

Bridget Jones’s Diary |

L.A. Confidential |

The Da Vinci Code |

Notting Hill |

2010 Releases |

2011 Releases |

2012 Releases |

Knight and Day |

Tower Heist |

Les Misérables |

Love & Other Drugs |

Cowboys & Aliens |

Anna Karenina |

J. Edgar |

Contraband |

|

The Dilemma |

Big Miracle |

|

Blue Crush 2 |

The point regarding quantity becomes self-evident and simple—only a larger organization that aggregates talent can produce on this larger scale. By corollary, to aggregate talent (e.g., producers and directors) the same organization needs to defer to talent on many issues, including the physical production of films. Coming full circle, the consequence of this aggregation is the resulting scale to take on different risks, including maintaining distribution overhead.

Range of Labels and Relationships

Range of Labels

One simple way to boost output is to create a number of film divisions. Almost all of the studios have availed themselves of this strategy, which segments risks into mini-brands and labels that usually have very specific parameters. These parameters are often defined by budget limit, but can also be differentiated by type of content. Fox, for example, created Fox Searchlight, which specializes in lower-budget fare, and similarly Universal created Focus; these are examples of smaller labels that take advantage of part of the larger studio infrastructure, but otherwise are tasked with a certain quantity output at lower budget ranges to diversify the studio’s overall portfolio.

Divisions and smaller labels are not strictly limited, though, to lower-budget films. Disney, for example, diversified into: (1) Walt Disney Pictures, which is generally limited to family and animated fare; (2) Touchstone, which is generally a releasing-only arm; (3) Hollywood Pictures; and (4) Miramax, which, when run by the Weinsteins, was a large, internally diversified studio releasing a comparable number of pictures in a year to the balance of the sister Disney labels.

Table 1.4 is a chart of some of the specialty labels under studio umbrellas and examples of the pictures made and/or released. This list used to be nearly twice as long, but driven by the 2008 recession, a number of labels have either been shuttered or sold off, including Paramount’s Vantage (There Will Be Blood), Disney’s Miramax (The Queen, No Country for Old Men), and Warner’s Warner Independent (Good Night and Good Luck, March of the Penguins). In fact, the New York Times, looking at the pending 2013 Oscars ceremony, noted, “the number of films released by specialty divisions of the major studios, which have backed Oscar winners like Slumdog Millionaire, from Fox Searchlight, fell to just 37 pictures last year, down 55 percent from 82 in 2002, according to the Motion Picture Association of America.”11

Table 1.4 Speciality Labels Under Studio Umbrellas

Studio |

Labels |

Example of Films in Sub-Label |

Sony |

Columbia |

|

Revolution |

||

Sony Classics |

Friends with Money |

|

Fox |

20th Century Fox Fox 2000 |

|

Fox Searchlight |

Slumdog Millionaire, Juno, |

|

Disney |

Walt Disney Pictures Touchstone Hollywood Pictures |

All Pixar releases (e.g., Finding Nemo, Cars) |

Warners |

Warner Bros. New Line |

The Lord of the Rings trilogy |

Paramount |

Paramount MTV/Nickelodeon |

|

Universal |

Universal Focus Features |

Brokeback Mountain, Jane Eyre |

Table 1.5 Breakdown of Fox Domestic Box Office

Label/Releasing Arm |

Division B.O. |

% of Total Studio B.O. |

20th Century Fox |

$1.1 billion |

72 |

Fox 2000 |

$272 million |

17 |

Fox Searchlight |

$162 million |

10 |

Fox Atomic |

$7 million |

1 |

Taking a snapshot from a few years ago at the height of specialty labels, with the exception of Paramount (where DreamWorks’ pictures—prior to its separation and move to Disney—accounted for a substantial percentage of the studio’s overall box office), the principal arm rather than the specialty labels accounted for greater than two-thirds of the studios’ overall domestic box office. Fox was a typical example. Table 1.5 is a breakdown of its total $1.56 billion 2006 domestic box office.12

Range of Relationships

In addition to subsidiary film divisions that specialize in certain genres or budget ranges or simply add volume, studios increase output via “housekeeping” deals with star producers and directors. Studios will create what are referred to as “first-look” deals where they pay the overhead of certain companies, including funding offices (e.g., on the studio lot), in return for a first option on financing and distributing a pitched property. (See the companion website for a discussion of firstlook deals and puts.)

Range of Budgets

Studios produce and finance projects within a wide range of budgets, with the distribution pattern creating a bell-type curve bounded by very low and very high budgets at the extremes; the average in this case represents the majority of output, expensive product in any other industry, but in studio terms midrange risk. An example of a high-budget label is Paramount’s former relationship with DreamWorks, where DreamWorks had the freedom to independently green-light movies with budgets up to $85 million, and reportedly up to $100 million if Steven Spielberg was directing.13

Low Budget It is possible to produce a film for under $1 million, as the proliferation of film festivals demonstrates. Technology has also brought the cost of filmmaking down, making it accessible to a wider range of filmmakers. Easy access to digital tools and software for editing is revolutionizing the business. Studios have the choice of commissioning lower-budget films directly, or, as discussed above, creating specialty labels focusing on this fare. Although there is no per se ceiling for low budget, the category implies a budget of under $10 million, and generally refers to under $5 million or $7 million.

Under the Radar What is truly under the radar is a moving target. With the cost of production escalating, films under $30 million, and especially under $20 million, have a different risk profile and can be categorized as “under the radar.” It may often be easier to jump-start a film in this range, and some studios will allow stars to dabble in this category for a project perceived as more risky (e.g., out of character). I do not mean to imply that this is a trivial sum, or that making a project in this range is easy. Rather, executives tacitly acknowledge that in the budget hierarchy there is a category between low and high budget that sometimes receives less scrutiny.

High Budget High budget is now a misnomer, for a typical budget is in fact high and people search for terms that differentiate the extremes, such as when a film costs more than $100 million. Accordingly, it is in this very wide range of somewhere above the then current perceived cutoff for a higher level of scrutiny or approval matrix to authorize (“under the radar” where the project is in a lower risk category) and $100 million that most films today fall. According to MPAA statistics, the average cost of a major MPAA member studio movie in 2007 was $70.8 million.14 (See Chapter 4 for 2010/2011 estimates by SNL Kagan).

Franchise or Tentpole Budget There is no formal range for this term of art, but when someone mentions “tentpole,” the budget is invariably more than $100 million, sometimes more than $200 million, and the studio is making an exception for a picture that it believes can become (or extend) a franchise. Moreover, a tentpole picture has the goal of lifting the whole studio’s fortunes, from specific economic return to driving packages of multiple films to intangible benefits. These are big-bet and often defining films, properties that are targeted for franchise or award purposes. Modern-day epics fall into this range, with Titanic leading the way. In other cases, films with a perceived “can’t fail” audience may justify an extraordinary budget, such as franchise sequels: Warner Bros. with Harry Potter, Sony with Spider-Man, and Disney with Star Wars and Marvel (e.g., Iron Man) fare. Variety, discussing the extraordinary number of big-budget tentpole sequels in the summer of 2007, noted that “five key tentpoles have an aggregate budget of $1.3 billion,” and continued: “Production costs continue to climb precipitously at the tentpole end, with Spider-Man 3, Pirates 3 (Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End), and Evan Almighty redefining the outer limits of spending. Last year’s discussion of how far past $200 million Superman Returns may have gone seems quaint by comparison.”15 What may have seemed exceptional a few years ago is now commonplace, and the summer is invariably stocked with high-budget sequels. Summer 2012 was no exception and included, among others, The Avengers, The Dark Knight Rises, The Amazing Spider-Man, The Bourne Legacy, Madagascar 3: Europe’s Most Wanted, and Men in Black 3.

This category of if-we-make-it-they-will-come blockbusters is a driver for the studios. There is frequently guaranteed interest and PR, cross-promotion opportunities galore, sequel and franchise potential, pre-sold games and merchandise, etc. Additionally, as discussed in other chapters, these tentpole pictures stake out certain prime weekends and holiday periods (e.g., in the U.S., Memorial Day, Christmas, Thanks giving) for release, and virtually guarantee the sale of other pictures in TV packages of films.

Why there is this range of budgets is again economically driven. All films can succeed or fail beyond rational expectations. Higher-budget films cost more because “insurance” factors are baked in: a star, a branded property, groundbreaking or spectacular special effects, and action sequences are all assumed to drive people to the theater (although, as discussed in Chapter 3, the highly variable nature of box office success is generally not tempered by such factors). With the extra costs come extra risks, as well as the need to share the upside with the stars/people/properties that are making it expensive in the first place. Accordingly, every studio dreams of the film that will cost less and break through—perhaps less glitzy, but driving more profits to the bottom line. Every studio would take 10 My Big Fat Greek Weddings or Slumdog Millionaires over an expensive action hero film. (In fact, the film Last Action Hero, starring Arnold Schwarzenegger, was Sony/Columbia’s big bet in 1993, but significantly underperformed at the box office, with a domestic take of $50 million against a reputed budget of close to $90 million, as famously chronicled in the book Hit & Run in the chapter “How They Built the Bomb.”16)

The Internet Wrinkle The Internet is allowing people to experiment with production at costs that are, in cases, so low that it is redefining what low budget means. It is hard to compare most online production to other media because the format has generally been shorter-form. As people continue to experiment, whether producing content intended only for Web viewing, hoping to utilize the medium for lower-cost pilots that can then migrate to TV, or producing series developed for on-demand viewing, it will be interesting to see whether budgets rise to match quality expectations of other media (as we are seeing with online originals from leaders such as Netflix and Hulu) or whether the Internet will drive a different cost structure (as has historically been the case) linked to new and evolving online content categories (see Chapters 3 and 7, including discussion of online leaders branching out to produce original content in Chapter 7).

Range of Genre and Demographic

While economics drive a portfolio strategy in terms of budget range, marketing drives the product mix in terms of sales. Accordingly, product targeted at different genres is produced to satisfy a variety of consumer appetites:

■ action

■ romance

■ comedy

■ thriller

■ drama

■ historical or reality-based stories

■ kids and family

■ musical

■ adult entertainment

These categories may seem obvious because they have become so ingrained. Simply check out the shelf headings at your local video store (if you can still find one), search categories for VOD options, or read film critics’ reviews—descriptions are peppered with Dewey decimal classification-type verbiage to categorize films. If the film is not easy to peg, then use a crossover term such as chick flick, or combine phrases such as “action thriller” or “romantic comedy.” Retailers’ and e-tailers’ creative labeling of shelves/sections and endless categories for awards further add to the lexicon of segmentation.

At some level, the categories become self-fulfilling, and demand is generated to fill the niche pipeline. How many romantic comedies do we have? If the studio cannot supply the genre, it starts to become more of a niche player, which can start to affect perceptions, relationships, and ultimately valuations. Categories come into and out of vogue (e.g., musicals), and about the only category where it has always been accepted to opt out is adult entertainment.

Range of Type/Style

If a portfolio strategy is not complicated enough, then draw a matrix combining different types of budget, genres, and relationships, and then layer on styles and types. Film style classifications include live-action movies, traditional animation, computer graphics-generated, etc. Today, even format comes into the mix, with 3D another variant.

These categories are more technical or process-driven, but serve to create yet another level of specialization or segmentation. For a studio, it is not enough to stop, for example, at the “kids market.” Conscious decisions need to be made about a portfolio within this limited category—how many titles, what budget range, how many animated versus live action, is there a range of budgets within the animation category, etc.

Other Markets—Video, Online, etc.

This proliferation of product cutting across every possible style and range has served to create outlets and demand for product beyond what is released in theaters or produced for TV. Demand in the children’s market, linked to the growth of home viewing starting with videocassettes, spawned the “made-for-video” business. At a video store, it became nearly impossible to discern whether sequels or spin-offs from films and name brands (Aladdin 2, The Scorpion King 2, The Lion King 1½, American Pie 4) were made for the movie or video market. (Note: The growth of this segment, and specific economics, are discussed in more detail in Chapter 5.)

Finally, online is expanding the production palate, with producers creating original product that ranges from features to shorts. In theory, distributing original Internet content should fall outside the studio system, for any producer with a website can stream content to anyone; hence, with the Internet enabling independence, why pay, or team, with a studio? The reason is that accompanying the near-zero barrier to entry with Internet distribution (bandwidth/site infrastructure is still needed) is the challenge of infinite competition and clutter. Accordingly, not only are networks and studios beginning to produce their own content, but they will start to affiliate with independents that need marketing assistance (and/or financing, as costs increase with talent inevitably demanding more in relation to growing revenues, or higher quality thresholds are sought). In fact, associating with a brand is one of the easiest ways to rise above clutter and attract viewers, and there is every reason to expect that, over time, studios/networks will add a portfolio of Internet originals, complementing the diversity found today in traditional media platforms. (See Chapter 7 regarding new growth of originals within online aggregators.)

Brand Creation versus Brand Extension

Finally, in terms of looking at the creation of product to fill the studio pipeline, one needs to look at the desire to find a branded property. Everyone is looking for that “sure thing,” and a property with built-in recognition and an assumed built-in audience theoretically lowers risk and gives marketing a jump-start.

Aside from the new idea, there are four treasure troves of ideas that serve as the lifeblood of Hollywood: the real world, books and comics, sequels, and spin-offs. I will only mention the real world in passing, given the obvious nature of creating dramas either set in historical settings or adaptations of real-life events (e.g., The King’s Speech, Saving Private Ryan, The Pianist, Argo, Zero Dark Thirty). However, it is worth noting that the explosion of user-generated content on the Internet (e.g., YouTube videos) is defining an entirely new source of material that producers are trying to exploit, as well as migrate to other media.

Books and comics are the largest source of branded fare. In fact, try to find a bestseller with a strong lead character today that is not being adapted (or at least optioned/developed) for the screen. Table 1.6 is a very small sampling.

Brand Extension: Sequels

Sequels are a relatively new phenomenon looking over the last 100 years of film in that these rights, while reserved by the studios, were not considered very valuable until the success of Jaws and Star Wars in the 1970s proved otherwise. George Lucas recognized the inherent value of sequels with Star Wars, and by retaining sequel and related rights to the original property built the most lucrative franchise in movie history. It only takes someone else making billions of dollars before others catch on, and today rights in sequels and spin-offs are cherished and fiercely negotiated for up front. In fact, of the top 25 films of the Box office in 2012, roughly two-thirds were either sequels or some form of derivative adaptation, with 7 of the top 10 being part of a series.17

Table 1.6 Examples of Film Adaptations of Books and Comics

Book |

Film |

Robert Ludlum books |

The Bourne series of movies |

Harry Potter books |

Harry Potter movies |

Tom Clancy books |

The Hunt for Red October |

John Grisham books |

The Pelican Brief, The Firm |

The Hunger Games books |

The Hunger Games movies |

Jane Austen novels |

Pride and Prejudice |

The Da Vinci Code |

The Da Vinci Code |

J.R.R. Tolkien books |

The Lord of the Rings movies |

Comic |

Film |

Batman |

Batman series of films |

Spider-Man |

Spider-Man series of films |

X-Men |

X-Men series of films |

Superman |

Superman series of films |

Iron Man |

Iron Man series of films |

A successful film can become a brand overnight, and since the 1980s, and especially the 1990s, the mantra has been once a movie reaches a certain box office level, executives immediately start thinking about making a sequel. Table 1.7 shows some prominent examples.

Sequels have become such a successful formula—of course they are not a guarantee; witness Babe: Pig in the City—that they have given birth to “prequels” and simultaneously produced sequels. Sequels used to be thought about in terms of what happens next: do they live, do they live happily ever after, what’s the next adventure …? Because movies are fantasy-based and have no boundaries, prequels are now becoming popular. In these movies, the audience learns how a character grew up—often without the famous actors from the original films even appearing. The Star Wars prequels (The Phantom Menace, Attack of the Clones, and Revenge of the Sith) serve as the most striking examples, absent stars such as Harrison Ford, Mark Hamill, and Carrie Fisher.

Additionally, with expensive films and effects, producers have started making more than one film in a series simultaneously to amortize costs. The Matrix Reloaded and The Matrix Revolutions, for example, were made together and were released six months apart in 2003 in the summer and at Christmas. The Lord of the Rings trilogy was green-lit by New Line Cinema to be made as a production bundle, and the more recent The Hobbit films, An Unexpected Journey, The Desolation of Smaug, and There and Back Again, are being filmed back to back in New Zealand (to achieve certain production efficiencies), with anticipated respective release dates by Warner Bros. of December 2012, 2013, and 2014. Similarly, Disney committed to making both Pirates of the Caribbean 2 and 3 at the same time, thus being able to keep the cast and crew together.

Table 1.7 Examples of Films and Their Sequels

Original Film |

Sequel(s) |

Jaws |

Jaws 2, Jaws 3 … |

Rocky |

Rocky II, Rocky III … Rocky Balboa |

Star Wars (Episode IV) |

The Empire Strikes Back (Episode V), Return of the Jedi (Episode VI), Episodes I, II, III, pending Episodes VII, VIII, IX |

Raiders of the Lost Ark |

Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skulll |

The Terminator |

Terminator 2: Judgment Day, Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines, Terminator Salvation |

The Mummy |

The Mummy Returns, The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor |

Home Alone |

Home Alone 2, 3, 4 |

Pirates of the Caribbean: |

Pirates of the Carribean 2: Dead Man’s Chest, |

The Curse of the Black Pearl |

3: At World’s End, 4: On Stranger Tides |

Spider-Man |

Spider-Man 2, 3, The Amazing Spider-Man |

Die Hard |

Die Hard 2, Die Hard with a Vengeance, Live Free or Die Hard, A Good Day to Die Hard |

Harry Potter series |

Harry Potter 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 |

Batman series |

Batman … The Dark Knight trilogy |

Brand Extension: Spin-Offs

The classic spin-off is when a character from one film/property is used to launch an ancillary franchise. In television, one of the best examples is Frasier. The Frasier character, played by Kelsey Grammer, appeared in Cheers, and when Cheers wound down the network launched Frasier as a new series. As most classic TV watchers know, Frasier was a pompous psychiatrist who was among the cast of support characters who regularly hung out at the Boston-based bar on the earlier Cheers. In the new show, the premise was that he has moved home to Seattle and practices psychiatry via hosting a local radio call-in show. The difference between a sequel and a spin-off should be quite clear. A sequel to Cheers would be, for example, a Cheers movie or Cheers reunion show where we saw what happened down the road.

An example of a movie spin-off would be The Scorpion King. The Scorpion King stars the villain from The Mummy, but does not continue with the other main characters, nor does it continue the quest or love interests pursued by the hero/main character in The Mummy or The Mummy Returns, played by Brendan Fraser. In fact, the distinction between The Mummy Returns and The Scorpion King paints a good distinction between a sequel (the former) and a spin-off (the latter). (Note: Not having worked on these, it is possible that in the specific contracts for these films they were not treated this way and were negotiated differently.)

Brand Extension: Remakes

A remake provides another category of brand extension, albeit one that is used less frequently than a sequel or spin-off. An example of a remake is Sabrina, where a classic film is remade with new lead actors and actresses. The original film, starring Audrey Hepburn, Humphrey Bogart, and William Holden, was remade using the same lead characters, same principal storyline, and same general locations, but the former cast is now updated with Julia Ormond, Harrison Ford, and Greg Kinnear.

Remakes are less common for a simple reason: it is natural for audiences to compare the remake with the original, and if the original is strong enough that it is worthy of remaking, then the new film better be strong enough to stand up to the original. Still, the formula of starting with a classic and substituting current stars seems a formula and risk often worth taking. Again, this is a classic example of brand extension with another variation on risk analysis.

Crossover to Other Markets: Sequels and Spin-Offs

Finally, there is the catchall crossover category where properties migrate across media:

■ films spawn TV shows (e.g., M*A*S*H, My Big Fat Greek Life, The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles)

■ TV series spawn films (e.g., Star Trek, Miami Vice, The Flintstones)

■ games spawn films (e.g., Lara Croft: Tomb Raider)

Sometimes a property becomes so successful and spawns so many permutations that it is nearly impossible to distinguish what came from what. The original Star Trek series certainly led to the success of spin-off series such as Star Trek: The Next Generation, but with further spin-offs and sequel movies from both the original series and spin-off series, the boundaries become blurred (and are becoming more so all the time, with a prequel to the Star Trek series, simply titled Star Trek, released theatrically in summer 2009, with its follow-up Star Trek Into Darkness launched in 2013). Maybe this is like the show’s mantra of “to go where no one has gone before” because the cumulative weight of episodes and movies has led to a Star Trek franchise that is bigger than the sum of its parts and almost unique in the business. It is, in fact, an example of brand extension where the brand has outgrown its origin and taken on a life of its own. (It certainly seemed that way when I attended a Royal Premiere in London of a new Star Trek film starring the cast of the TV series Star Trek: The Next Generation, and an actress playing an alien doctor sat next to Prince Charles during the playing of “God Save the Queen.” If this is not an example of the international reach of brand extension, then I don’t know what is.)

Windows and Film Ultimates: Life-Cycle Management of Intellectual Property Assets

While the following discussion focuses on film, most original linear media has now found additional sales windows outside of its launch platform. TV shows are now released on DVD, downloaded, seen on cable, watched in syndication, and accessed online/via on-the-go devices. The ability to adapt linear video content to multiple viewing platforms—at different times and for differentiated prices—is the essence of the Ulin’s Rule continuum, which allows distributors to maximize the lifetime value of a single piece of intellectual property. A property such as Star Wars or Harry Potter can generate revenues in the billions of dollars over time, taking advantage of multiple consumption opportunities that at once expand access to those who did not view the production initially and entice those who did watch to consume the show/film again and again. This unique sales cycle is the envy of games producers, who have still not innovated material downstream sales platforms, as well as the challenge of the day for how best to utilize the Web. The following overview focuses on film, but highlights the key points of consumption that all media needs either to leverage, or compete with, depending on where one sits in the chain.

Film: Primary Distribution Windows

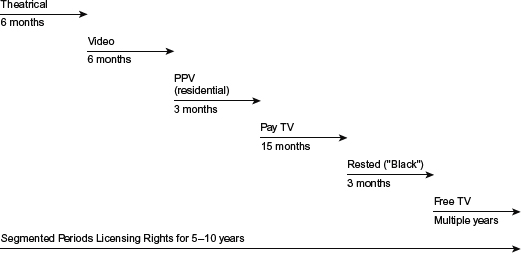

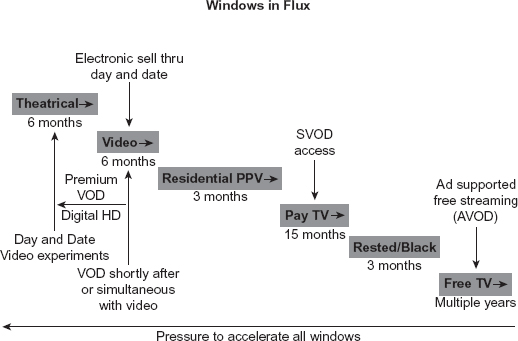

It is common to tie up the rights to a movie for five or more years shortly after it has been released in theaters, and, in cases, before the movie is even released. In some cases, movie rights may be committed for more than 10 years. Carving out exclusive shorter periods of exploitation (“windows”) during these several years creates the timesensitive individual business segments that form the continuum of film distribution.

Typically, a film will be launched with a bang in theaters, with the distributor investing heavily in marketing; the initial theatrical release engine then fuels downstream markets and revenues for years to come. After theatrical release, the film will be exclusively licensed for broadcast, viewing, or sale in a specified limited market for a defined length of time. The following are the primary windows and rights through which films have historically been distributed:

■ theatrical

■ video and DVD/Blu-ray

■ pay television

■ free television

■ hotel/motel

■ airline

■ PPV/VOD