Internet Distribution and a New Paradigm

On-Demand and Multi-Screen Access, Cord-Cutting, Online Originals, Cloud Applications, Social Media, and More

|

More content from this chapter is available at www.focalpress.com/9780240824239 |

The pace of change in the digital distribution of video-based media has been so torrid that much of what I discussed in the first edition of this book is fully outdated. Cloud applications had not penetrated the mass market, tablets did not exist, the app ecosystem had just been introduced, social media was in its infancy, and cord-cutting was not part of the vernacular. What is startling about the delivery and consumption shift led by cloud-based infrastructure, over-the-top access, personalization of TV, and streaming aggregators vying to become new networks is that this new paradigm follows directly on the heels of a period that was itself considered revolutionary. Traditional networks and video outlets, still critical and relevant as the prior chapters have illustrated, are akin to boxers having withstood a first punch that scared them, and a second blow that dazed—the pending question is whether, in fact, the cumulative shocks will ultimately create a knockout. The old boxer, wobbly but wily, is still upright because content continues to be king, and the most compelling content is vertically integrated within the old distribution infrastructure; moreover, traditional distributors are increasingly finding ways to license and exploit their prized content via on-demand systems and on-the-go outlets, using their leverage to turn would-be competitors into new revenue sources. The challenging question remains, though, whether we are approaching a tipping point when revenue from VOD access overtakes traditional sources, rather than the new channels of access being merely a new window to be carefully exploited and caged. If 2006–2008 was the period when the boxer climbed into the ring to defend his title, then I would argue the ensuing few years pushed him against the ropes; in the next several years, we will see that long-feared tipping point when the ropes come down and the digital distribution genie is no longer a pretender to the crown. The challenge to content owners, going back to Ulin’s Rule, is to balance the streams and impose enough window discipline that persistent VOD is not the only window—for if it is, as discussed in Chapter 1 and throughout this book, then creators will see a continuing erosion of revenue, and the challenge of how to produce and finance premium content will become even more acute.

Not Very Old History—The New Millennium’s Wave of Changes in Consuming Video Content

Before I discuss the impact of this wave of new changes (streaming aggregators competing as networks, advances in over-the-top access, cord-cutting, success of Internet-enabled and cloud-based services, professionals leveraging the broadcast-yourself model, social media and related personalized methods of consuming content, etc.), I want to take a step backwards to set the context. In my first edition, I started this chapter by noting: “The years 2006–2008 will be viewed historically as revolutionizing how consumers watched, accessed, and paid for video-based content. The explosion of video on the Web came about suddenly, fulfilling the promise of what many envisioned almost a decade earlier before the dot-com bust. Much of the change was enabled by technology, such as widely adopted DRM solutions, increased broadband penetration, and the advent of video-capable iPods and then iPhones.” The confluence of several factors ushered in the digital revolution that threatened to upset and cannibalize traditional TV and video distribution:

■ the “Googlization” of the world and proving the Web can be monetized;

■ the YouTube and Hulu generation, instant streaming, and the emergence of free video-on-demand (VOD);

■ the introduction of the video iPod and then the iPhone (and subsequently the iTunes App Store);

■ implementation of reliable, flexible digital rights management (DRM) technology;

■ traditional distributors, not pirates, legally making the market; and

■ mass-market adoption of high-speed Internet access (fixed and wireless), together with the adoption of common standards.

Just as software drives hardware (content is king), compelling new user experiences (enabled by pioneering technology) tend to drive digital distribution channels, and there was a gold rush to develop platforms realizing the new on-demand, on-the-go paradigm. Apple, Hulu, and YouTube are among the companies that leveraged the serendipitous moment in time to launch the right site or products (e.g., YouTube offering free file hosting, together with a user-friendly interface for uploading and accessing content, at the same time allowing users to easily download the flash video application for free). The online video revolution was unleashed, and whether a new entrant (e.g., YouTube, Hulu) or market leader (e.g., Amazon, Netflix, Apple), all companies started experimenting with business models that could tap into but would not stifle the almost obsessive new consumer habits.

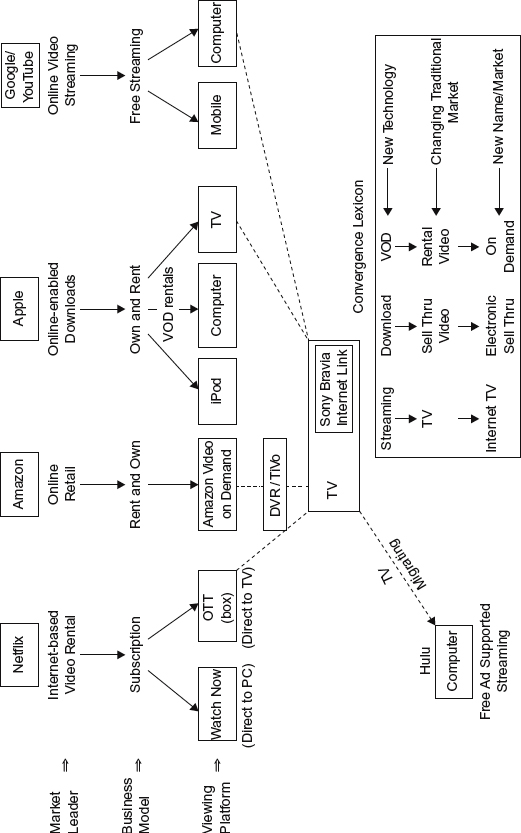

Rationalizing the Burst of Convergence

With so many moving parts, it is nearly impossible to clearly diagram this burst of convergence. Figure 7.1 is an attempt to capture the following key factors: (1) the online market is largely driven by deep-pocketed online market leaders in related sectors, not by pirates nor by traditional media distributors; (2) convergence is not business model-dependent, as subscription, rental, and free delivery models are all being deployed; (3) TV remains the Holy Grail to many, as whatever the primary viewing platform online market sector leaders are looking for ways to leverage content delivery to the TV screen (or, in cases, a second or third simultaneous screen, and as described later, trying to supplement offerings with original content and become TV itself); and (4) technology is enabling the migration of traditional media markets (e.g., TV, sell-through video, video rentals) into new online adapted versions of the traditional markets. (Note: For simplicity, I have omitted the further layer of delivery to TV via gaming systems.)

Figure 7.1 Market Segment Leaders That Pioneered New Technology Applications: Digital-Focused Companies Making the Market (2006–2008)

Again, it is important to emphasize that these were not small players angling to join the space. At the time, this represented the market leader in Internet-based video rental (Netflix), the market leader in Internet consumer shopping, including the top Internet site for DVD purchases (Amazon), the global pioneer in downloading media content transitioning from music to all media (Apple), and the top Internet search engine, whose stock had just made it the most valuable Internet company in the world (Google). Of equal importance to who was entering the market was who was not. Unlike the music space, there were no Napsters emerging as viable leaders. While some peer-to-peer companies may have been dominating Internet traffic, the upstarts were wannabes; funded by venture capitalists, the technology was not dominating the models, and in fact the technology was fast becoming a commodity and playing second fiddle to the larger brands. Perhaps the seminal Grokster case plus the earlier focus of the studios and the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) to squelch illegal downloads (and head off the woes that beset the music industry) together created a safe environment for companies to jump in and focus on the legal business. The issues debated were not the illegality of downloads, but the economic models of subscription versus pay-per-buy, adoption rates, conversion rates, etc. Against this landscape, the debate quickly became not “Would video downloads be viable?” but “Who would compete with Apple for the market, how fast would it grow, and would an economic model develop to rival iPod’s flat $1.99 pricing for any download (an issue that now feels ancient, though only a few years old)?”

The key elements were that the product and technology were not perceived as intermediary, waiting for adoption of the next evolutionary product (as was the case with laserdisc before DVD); rather, the download market and portable devices enabling the market were perceived as permanent, with upgrades expected akin to the PC market. Just like the next laptop would be faster, sleeker, etc. (though at the time no one was yet thinking about the move to tablets), there was a built-in expectation that the next generation of downloads would be faster with more storage capacity. In a flash, the consumer adapted to the digital world, and did not even notice that content-viewing was being thought of in computer expectations rather than TV or video terms.

The new variety of offerings tempting consumers—from portability to living room convergence, from rental to ownership, from free to paid-for content—was dizzying and confusing. And yet, as we now know, the disruptive changes emerging were just the tip of the iceberg.

Fear Factor I: Panic to Avoid the Fate of the Music Industry

The quick pace of change and related murky legal waters initially cast fear among traditional distributors that the lifeblood of their business may be snatched away before they could even respond (with some arguing via illegal means). The crisis in the music industry, which was first paralyzed by online piracy and then rescued, in part, by iTunes, was threatening to similarly upend visual media as peer-to-peer services enabled file sharing of movies. Long-form video content, which previously had been thought to be somewhat immune given the inherent barriers of hour-plus stories and correspondingly large file sizes (i.e., a film cannot be divided into independent consumptive elements, like a record can be split into songs) was suddenly vulnerable. Whether melodramatic or not, the fate of media was perceived to be in the balance—and to many it still is.1

While there are no fully reliable statistics on illegal downloads versus legal buys, most industry insiders would admit that legal watching is simply a fraction of overall Internet viewing. At first, there was a proliferation of illegal services, and the motion picture industry, like the music industry before, had to contend with how to convert people to pay for something they were quickly becoming accustomed to receiving for free. The biggest danger came from peer-to-peer services that could virally distribute thousands of copies of a film almost instantly.

The threat of piracy, and the impact of the new breed of peer-to-peer services, was dealt with in 2005 by the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer v. Grokster; this case, discussed in Chapter 2, was a turning point for how Internet piracy would be perceived and contained. For here, it is simply worth reiterating that the peer-to-peer file-sharing services, such as Grokster, Kazaa, and BitTorrent, enabled individual users to efficiently share and download movies and other video content for free. There was enormous pressure, both at the government and industry level, to nip this in the bud and avoid a crisis similar to that experienced by the music industry prior to the white knight arrival of iPod and iPod lookalikes. Additionally, because the Web knows no geographic boundaries, it has become equally critical for foreign jurisdictions to act similarly. The Swedish Court’s 2009 jailing of individuals behind Pirate Bay—a notorious site thumbing its nose at the notion of copyright protection—and the FBI’s shutting down of Megaupload, paired with the indictment of its founder Kim Dotcom,2 bolstered the trend fought for in Grokster.3

A key technological advance inherent to controlling piracy, as well as essential to managing the delivery of and access to content via the Internet, was the improvement in encryption systems. History is repeating itself: the prior fear was that DVDs provided perfect digital copies that could be pirated (holding back the introduction of DVDs), and now the same issues are surfacing via digital versions distributed through the Internet, with the scenario complicated by the need to authenticate specific devices and users. Licensors are anxious about their jewels being placed on someone’s hard drive (or shareable device), and all the implications that go with that loss of control. Yes, the files are encrypted to ensure that your copy is truly on the end of a digital yo-yo, with the distributing service able to pull the strings to cut off the copy, pull it back after a set amount of time, and virtually control its ability to be played and copied (despite the fact it is stored on your computer, and now also on your tablet and in the cloud). All of this is critically important in the short term, but to many it is less important downstream, where they question the feasibility of imposing these levels of controls on consumers. To the extent people break the rules, services are shoring up safeguards and facilitating a path to market maturity where violators will hopefully be contained and be relegated to the same danger level as DVD pirates: a serious threat to be managed, but hopefully not a category killer (see further discussion in the companion website).

Finally, coming back to the urgency of thwarting peer-to-peer-enabled piracy, exacerbating the need for the studios to act and restore a sense of equilibrium, was the fact that change was taking place on the heels of the decline and peril experienced by the music industry. There was a feeling that this stage of change was somehow fundamentally different than prior iterative technological advances (which, despite previous fears, had served to expand total revenues); moreover, there was a realization that without action, the historical safety nets could not be counted on to preserve current markets.

Because everyone was unsure whether online would be an ancillary market or instead be the whale that could swallow the whole, as well as where lines should be drawn concerning viral access, people were scared and tending to take absolutist positions. With no obvious solutions, unproven monetization, different metrics than traditionally employed, fear of piracy, conflict between protecting valuable windows versus leveraging the Web’s consumer marketing reach, and unprecedented adoption rates (e.g., YouTube, Facebook), media conglomerates at once acknowledged the changes were real and struggled to craft solutions that would expand rather than shrink the revenue pie.

Fear Factor II: Would On-Demand and Download Markets be Less than Substitutional for Traditional Markets (Pessimistically Discounting the Potential of the Markets Being Addictive)?

No matter what hype, until the on-demand and download markets approach revenue levels of the video market, they still represent secondary revenue streams. Video-on-demand is already perceived as the video of the future, and advertising-supported VOD (AVOD)/FVOD will be a critical element of TV going forward (see Hulu discussion on page 377), but the associated revenues from each remain a small fraction of the larger markets; moreover, it is not certain which markets will actually converge (is SVOD the same as pay TV?), nor whether different access methods will be complementary or whole segments will be eliminated. This is a critical issue given the Ulin’s Rule factors outlined throughout: historically, licensing content through windows fostering exclusivity, repeat consumption, variable timing, and price points has optimized the pie. Because VOD can largely fulfill the consumer’s appetite for access to all “when I want it, how I want it, where I want it,” there was a simultaneous attack on not just the concept of windows, but more fundamentally the elements of exclusivity and timing upon which windows are constructed.

Economically, one of the key factors underlying this jeopardy is straightforward: online trends toward nonexclusive access, and TV licensing in particular is premised on exclusive windows. The much-hyped long tail of the Internet affords a broader platform for access to library titles than has ever existed before, but the long tail does not inherently prove enhanced monetization of that content. (Note: Most content people want to see already finds a home via traditional media (e.g., Brady Bunch reruns on Nick@Nite); see also discussion of marginalized return of the long tail in Chapters 1 and 6.) The jury is out. Even if access to a program and consumption dramatically expands, that would still not ensure greater licensed revenues than could be achieved from competition over exclusive rights. The threat presented by online is that expanded access and consumption could, for the first time, actually shrink the pie if that expansion is enabled by free and nonexclusive access. If windows are not choreographed and controlled but content is instead subject to the free-for-all of the Web, then many fear the bar will be lowered. Moreover, lower distribution costs, given the elimination of physical goods, does not guarantee higher margins, given the downward pricing pressures online.

In summary, the safety net that new technology would expand revenues—as had repeatedly happened, such as when video did not cannibalize TV, as early pundits feared—was in jeopardy, and executives in various sectors were left with the challenge of inventing a new market and revenue models or else, as in television, watch their repeat licensing revenues fall in the face of earlier online access that did not make up for their losses. Although people were witnessing a revolution of how programming would be consumed over the Internet as opposed to traditional TV, few were as prescient about the scope and speed as Bill Gates. At the 2007 World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, he proclaimed: “I’m stunned how people aren’t seeing that with TV, in five years from now, people will laugh at what we’ve had.”4 New markets and models have indeed emerged (e.g., catch-up via Hulu, subscription streaming via Netflix), giving hope that at least a balance can be restored. It is still too early to declare whether such new models will ultimately be additive. What is abundantly clear, though, is that consumers will demand multi-platform access, with repeat consumption in the future meaning consuming content via a smartphone, game console, PC, tablet, Internet-enabled TV, OTT hardware box, Blu-ray player, etc., in a pattern dictated more by convenience than a distributor-crafted linear sequence.

(See the companion website for more history, including “The Explosion of Video on the Web,” “Change Could Have Been Even Faster (Speed and Quality as Limitations to Adoption and Downloads),” “To DRM or not to DRM,” “Déjà Vu—Internet Piracy Control Measures Reminiscent of Fear of Perfect DVD Copies,” “Common Platform—Behind The Scenes Accelerant,” and “A Landscape Changed Virtually Overnight by iPods.”)

As earlier posited, VOD is blurring the lines of just what TV is, and I have long argued that Netflix, which is generally thought of as a video service given its DVD-by-mail roots, is more aptly compared to pay television; after all, pay TV, historically, is an aggregation subscription business, giving customers access to a variety of top programming for a fixed monthly fee. The market is now starting to prove this point, with Netflix acquiring Disney titles (available starting 2016), which had previously been with U.S. pay service Starz, for availability in the pay TV window. As a punctuation point on Internet services competing head-on with pay TV, the UK’s competition authority Ofcom announced that it was ceasing its investigation into Sky’s position of dominance in the UK pay TV market because the emergence of Lovefilm (acquired by Amazon) and Netflix had fundamentally altered the competitive landscape.5

As discussed in Chapter 6, though, there are critical challenges to the pay TV business, which, not surprisingly, are starting to impact the strategy of other aggregators: (1) cost of content is expensive, especially when trying to secure exclusive access (as noted in Chapter 6, a single studio’s output deal can guarantee over $1 billion over an extended license); (2) aggregation in and of itself is not enough to retain customers, and to remain competitive pay TV services need to offer compelling original content; and (3) aggregating third-party content in a downstream window in an increasingly VOD world creates a bit of an identity crisis for a pure aggregator. Put another way, if an aggregator has to shell out big bucks for content, and at the same time sees its aggregation of content becoming a supplement rather than the driver of the business (How many people subscribe to HBO to get the movies they could have already seen in a prior VOD window versus those who want to watch Entourage or Game of Thrones?), what should their strategy be? The simple answer is focus on the driver that attracts and keeps customers: original content.

If this is the trend wrought by increasingly ubiquitous VOD access to content, then it was inevitable that other aggregation-based businesses started to modify their branding and offerings with original content. When I started to revise this chapter, based on the foregoing premise, I believed that leading services would launch originals—Netflix was among the first to announce, then followed by YouTube. In fact, in a draft, I had written, “I am not surprised that the likes of Netflix and YouTube in 2012 started to delve into originals; rather, I am surprised it took so long.” Not long afterwards, Hulu and Amazon jumped in as well, saving me from this edition being immediately out of date on its 2013 release. Until recently, the U.S. market was the primary testing ground for this trend, but as the leading players branch out internationally the need for originals is becoming evident market by market. In the UK, Televisual, in an article entitled “Digital Giants Go TV Shopping,” noted that Netflix, Amazon, and Hulu were all commissioning original shows to make their respective VOD services stand out. The article then went on to note of the testing ground: “catch-up services are proliferating and it is increasingly easy to access repeats on services such as YouView, 4oD and the BBC iPlayer—not to mention traditional services such as UKTV’s suite of channels. So the leading players realized they have to offer something unique themselves in order to attract viewers. The move echoes Sky’s strategy (though not its spend) of investing in original British content as part of its effort to stop churn and hold on to its 10 million-plus subscribers.”6

The penultimate question, then, becomes whether streaming aggregators can migrate their brand, and how well in the future they compete head-on with, for example, HBO Go. Why should HBO not ask for the streaming rights to content they are already paying a premium price for, and position itself as the leader in aggregating streaming content (having been the innovator of subscription aggregation in the first place)? Maybe the battle lines will be drawn over timing (current content versus library), but this becomes a challenging difference to a consumer that no longer wants to wait.

Netflix, YouTube, Hulu, and Amazon Shift Gears

Netflix

In 2011, Netflix announced that it had partnered with Media Rights Capital and Academy Award-nominated director David Fincher (The Social Network, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo) to produce a political drama starring Kevin Spacey entitled House of Cards. Reputed to cost $100 million to produce, Netflix is betting more than cash on its strategy of adding originals. After touting that total viewing exceeded 1 billion hours in June 2012, Netflix CEO Reed Hastings predicted via a Facebook post: “When House of Cards and Arrested Development debut, we’ll blow these records away.”7 Arrested Development, though not a purely original series, is an interesting example of how online services are also providing a new market for series that were cancelled on traditional television (see also discussion of online and TV development in Chapter 2); whereas cable, on occasion, created a new home for series whose ratings could no longer justify a network run, online and on-demand platforms may now provide that second chance for successful shows with smaller, though avid, fan bases (Arrested Development having been a multiple Emmy award winner on Fox, with a cult following, while never achieving hit ratings).

Despite this promise (which no doubt has a white knight feeling to avid fans), Netflix’s test with Arrested Development also provides an example of the challenges inherent in bringing back an older series. The ability to “tie up” actors for continuing seasons is both a staple and thorn of producers, and once a series ceases production, the cast and crew scatter to new projects. This was one of the pivotal reasons that Netflix, when bringing back Arrested Development, had to announce that after one new season, it was likely it would not be able to continue the series, with CEO Reed Hastings even advising that it would be “one-off” and “not repeatable.”8 Launching a new series accordingly brings control and all the other associated benefits.

To move beyond an experiment utilizing only a small fraction of its content budget for original shows,9 as well as compete with all the other services now following suit commissioning online original premium content, Netflix needs to commit to a substantial ongoing portfolio of original properties and leverage the shift in its offerings—a direction it signaled taking, with its chief content officer, Ted Sarandos, advising post the May 2013 launch of Arrested Development that Netflix planned to quickly double its volume of originals, devoting 15 percent of its budget to original programming, up from roughly 5 percent in 2013.10 Clearly, though, even with limited fare, Netflix is starting to encroach on the turf of established pay channels much like it snuck up on the prior video market leaders. The Wall Street Journal acknowledged just this shift: “The move to start licensing original shows for its streaming service thrusts Netflix into more direct competition with premium-cable networks like Time Warner Inc.’s HBO, CBS Corp.’s Showtime, and Liberty Media Corp.’s Starz, which also run pricey original series alongside Hollywood movies.”11 If Netflix achieves even modest ongoing success with its original programming, I fully expect that this trend will continue and that Netflix will be increasingly viewed in “network” terms—in fact, this is already happening as reflected in reactions to Netflix’s groundbreaking fourteen Emmy nominations in 2013.12

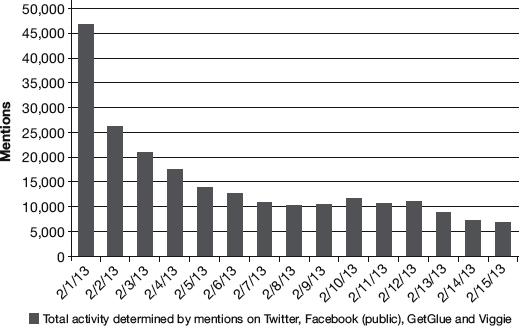

What was perhaps most interesting about the launch of House of Cards on Netflix (February 2013) was the debate it spawned about binge viewing versus traditional appointment viewing. Perhaps because the show’s success could not be benchmarked against traditional TV since there were no ratings attached—no advertising, so nothing for Nielsen to monitor, a point which punctuates my earlier comment about the need for evolved metrics that capture and harmonize downstream viewing via a plethora of devices—analysts were looking to social media and other barometers to measure performance. In doing so, though, what became evident was the drop-off in conversation from binge viewing, as evidenced by the graph from Trendrr shown in Figure 7.2, as reproduced in the New York Times.

The headlines, interestingly, were not so much about the novelty of original content via Netflix, but rather about the viewing pattern that Netflix enabled by making all the episodes available at once: thus compressing the window and allowing binge/marathon viewing. Examples of headlines from the New York Times were: “Does the House of Cards All-You-Can-Eat Buffet Spoil Social Viewing?” and “Release of 13 Episodes Redefines Spoiler Alert”13 The debate turned to how much the water cooler conversation helps market a show, whether a big bang launch akin to movies was better, or if there is an inherent benefit to the serial nature of TV. In analyzing the social media falloff, where trends indicated the debut would have put House of Cards among the top shows initially (at least measured by level of conversations) before its falloff, the New York Times noted: “Absent the long tail of online chatter, Netflix is missing out on the secondary bounce of people who want to catch up with the show when they see that many others are talking about it.”14 The Times also quoted the CEO of Trendrr, Mark Ghuneim, regarding the pattern: “That lack of scarcity, of windowing like traditional television, means that they aren’t going to get those spikes in conversation … After you binge, you don’t have a place to talk about it because everyone is on a different cadence.”

Figure 7.2 House of Cards: Social Media Decay Post Binge Viewing Launch

© Trendrr 2013, reproduced by permission of Trendrr.

It is far too early to tell what the ultimate effect and patterns will be, but this points to a classic disruptive concern when everyone is talking about windows, the long tail, and social media trends. What could be a further cry from the launch of a new network sitcom at 8:30 p.m. on Thursday evening? As online leaders morph into new kinds of “networks,” not only is competition ratcheted up, but the conventional norms of how, when, and where we watch TV are now being blended in a new kind of online test tube that we do not yet know how to measure.

YouTube

YouTube, though not a subscription-based aggregator, is an aggregator at its core and is likewise migrating its profile to now offer original premium content. The challenge for YouTube has always been twofold: (1) it grew like wildfire grounded in pure discovery with little to no editorial filtering; and (2) the lack of editorial filtering scared off brand advertising that was wary of being associated with subpar content. Accordingly, while YouTube succeeded in establishing thousands (in fact, going into 2012, more than 20,000) of content partners with whom it shared advertising revenues, the associated advertising rates tended to be a fraction of those commanded by professional content.15

How to change this construct has been a continuing puzzle for YouTube, because user-generated content (UGC) is the heart of YouTube: content created by individuals and uploaded to the Web for anyone to see and potentially share. The company’s early growth was directly correlated to the ease of uploading a video file, and continued when uploading images and video from cell phones created a new level of access and potential. A generation of citizen reporters was enabled, and suddenly nothing was private. A recording of Saddam Hussein’s hanging exemplified that there were now, in essence, no limits to what could be uploaded and accessed. The new gatekeeper was editorial and search—not content creation, access, or technology—and its new owner Google was loathe to undermine the power of search. In its acquisition of YouTube, Google implicitly was betting it could crack the challenge of UGC. It knew the advertising categories were there, whether banners or video advertisements, and that the expectations of free, coupled with concerns about juxtaposing brand advertising next to unfiltered and “unprofessional” content (think silly pet videos), was an impediment to efficient monetization. Google simply had the deep pockets to experiment with models, inherently believing that, with an audience, it would solve the advertising issue much as it had pioneered success with its Chrome browser and Google AdSense.

I asked Alex Carlos, YouTube’s head of entertainment, what progress had been made in capturing value from UGC, and he noted:

Huge progress. More than a third of YouTube’s monetizable views come via our Content ID technology, which allows labels and movie studios to share in the revenue from user-uploaded clips. Record labels alone are earning hundreds of millions of dollars a year on YouTube. We see this becoming a significant revenue stream for the entertainment industry.

Even accepting YouTube’s improved monetization of UGC, economically creating some form of editorial filter was inevitable, and accordingly the launch of “professional channels,” while delayed, should not come as a surprise. This is simply the next evolution of YouTube trying to bridge the divide and be TV for the next generation.

In describing how YouTube does not merely want to be “like a TV network,” but rather be TV itself, the New York Times asked the question that analysts had been wondering for years and that YouTube, wedded to its culture of discovery, had been resisting during its patient wait for enhanced monetization schemes: “But how much more could YouTube make if it could sell advertising based on predictable viewership for specific content—in other words, if it could adapt itself to the planning and budgeting cycles of the people who have real money to spend, and allow for the kind of advance marketing that the film and television industries depend on? So get used to channels. The only questions are what they will be and how well they will work.”16

While the new U.S. channels are still developing, the scope and investment is sizeable: YouTube is creating around 100 new online video channels, with reports of $100 million to be invested in advances to content creators/providers; the list of celebrities involved is also significant, ranging from recording artists (e.g., Madonna, Jay-Z), to actors (e.g., Ashton Kutcher, Rainn Wilson, Sophia Vergara, Amy Poehler), to sports and extreme sports stars (e.g., Shaquille O’Neal, Tony Hawke), to cultural, self-help, and training gurus (e.g., Deepak Chopra, Jillian Michaels).17 Further, the range of programming is designed to compete with the portfolio offered by cable providers, and includes news and fashion channels in partnership with major brands such as Thomson Reuters, the Wall Street Journal, and Cosmopolitan. In fact, as summarized by the Wall Street Journal, the ultimate breadth of programming will look a lot like basic cable: “The channels will span 19 categories such as pop culture, sports, music and health, entertainment tailored to African-Americans and Hispanics, animal lovers, mothers, teens, and home and garden enthusiasts … In addition to generating about 25 original hours of programming every day, an additional 20 or so ‘library TV’ hours, or existing content that may have been previously broadcast on TV, would be uploaded to YouTube daily on the channels.”18

As part of launching (and monetizing) its new suite of channels, YouTube hosted “Brandcast” in May 2012; this was billed as YouTube’s first major event at the advertising industry upfronts, and was targted to introduce the new YouTube channels and related Web brands to potential advertisers. As part of these upfronts, YouTube announced several new partnerships, including:

1. WIGS (www.youtube.com/wigs), a channel created/programmed by Jon Avent (Black Swan, Risky Business) and Rodrigo Garcia (Albert Nobbs, In Treatment) devoted to women’s lives, featuring scripted series, unscripted content, shorts, and documentaries (with stars ranging from Jennifer Garner, Julia Stiles, and Virginia Madsen featured in initial series, and Jennifer Beals, Dakota Fanning, and Alison Janney committed to upcoming fare); and

2. a Team USA channel (www.youtube.com/teamusa), sponsored by AT&T, delivered by by the U.S. Olympic Committee, featuring original content relating to 2012 Olympic athletes, as well as potential Olympians and past heroes.19

As part of the press release announcing new partners and channels, and the hosting of Brandcast, YouTube boasted: “By the end of July, there will be 25 hours of new original content on YouTube each day.”20

Against this background of new channel launches, I turned again to Alex Carlos, head of entertainment at YouTube, and asked whether YouTube perceived this launch and focus on new channels as reinventing TV, and how the company viewed the associated fund underwriting programming. He advised:

We’re betting that the Internet is going to bring a new group of channels that’s more niche and interactive than currently available. Our goal is for YouTube to become the defining platform for this next generation of channels.

Think about what we’re all into today—we kiteboard, we do yoga, we paddleboard, we’re into vegan cooking—we don’t have channels that reflect that on TV because the start-up and operating costs are too high. That’s why this complements the existing TV offering. Just as audiences shifted from broad to more narrow programming when cable came onto the scene in the late 1970s and early 1980s, we think audience will continue to shift—spending more and more time with niche subject matter—because now the distribution landscape of online video allows for very discrete interests and audiences to be served. With YouTube, a whole new world of content can now make it to the screen.

The fund we created represents YouTube putting some skin in the game—it’s small, but it’s symbolic.

Not long after YouTube’s announcement of its U.S.-based channels, it essentially doubled down its bet, announcing the launch of 60 new video channels in Europe. Making the announcement on the eve of the annual TV programming market MIPCOM (Cannes, October 2012), YouTube not only announced channels across the UK, Germany, and France, but also touted channel programming coming from industry heavyweights BBC Worldwide, Endemol (the Dutch company behind Big Brother), and Freemantle Media (American Idol producer, now part of Germany’s Bertelsmann). The mix of channels and programming will mimic the portfolio goals of the U.S., ranging from major brands, to niche programming, to celebrity-led content—such as U.K. celebrity chef-produced “The Jamie Oliver Food Channel.”21 While the scope of YouTube’s move appears grand, on a per-country level the investment is not particularly risky given the company’s overall size. In the UK, where it has been reported the annual budget for original content is £10 million, Televisual, in quoting Pact’s chief executive, referred to the amount relative to broadcasters ITV and Channel 4’s budgets as “tiny,” and continued on YouTube’s hedged strategy: “… with YouTube providing an advance which they then earn back through advertising. Only then does YouTube split ad revenues with content creators.”22 Perhaps those seeking online funding and complaining about deal structures ought to read Chapter 10—I would love to find a distributor that started sharing upside before recouping a material part of its investment. YouTube and others investing in online content are still exercising prudence, and “new media” models are already starting to look a lot like traditional media.

Hulu

In the second quarter of 2012, in advance of the advertising upfronts, Hulu jumped on the original content bandwagon. In many ways, though, as an aggregator, it was the least obvious service to take the foray into development. This is because Hulu was started as a “catch-up” service for original programming, and its content consists of new original shows from its primary owners Fox, ABC, and NBC. Nevertheless, whether as a natural outgrowth of branding an aggregator as described above, or whether a necessary strategy to remain competitive vis-à-vis other key online services (e.g., YouTube, Netflix), Hulu announced that it was licensing 13 original TV series to be available exclusively online23 (Note: The exclusivity element to drive value consistent with Ulin’s Rule; UK’s Televisual noting that Hulu “has a program acquistion budget of $500 million for 2012 and is keen to sign exclusive deals for content to differentiate itself from its competitors.”24)

Although there are no formal “digital upfronts,” a trend started to emerge in spring 2012 of the online leaders making presentations and initiating de facto upfronts, in an effort to compete with traditional TV head to head and siphon off part of the upfront kitty to underwrite their online original content (see also prior YouTube discussion). Hulu kicked off this process, and announced five new “series” (and others in development), including:

1. A Day in the Life, a documentary series executive produced by Morgan Spurlock; and

2. The Awesomes, a Seth Meyers- and Michael Shoemaker-backed series set for 2013, pitched as “An unassuming superhero and his cohorts battle diabolical villains, paparazzi, and a less-than-ideal reputation as second-class crime fighters.”25

By the beginning of 2013, Hulu confirmed its seriousness in the space, with an expanded lineup totaling 20 original series, including cop show Braquo about Paris cops on the edge (in the spirit of shows such as The Wire, Southland, and The Shield), The Wrong Mans, a comedy spy series coproduced with the BBC, adult animated comedy Mother Up (starring Eva Longoria), and Israeli drama Prisoners of War (in the spirit of Homeland).26 Additionally, Hulu announced a deal with production company Prospect Park to bring back classic soap opera One Life to Live and All My Children.27 If the soaps prove successful, it will demonstrate a major leap forward for online fare, given the seeming disconnect between the generally younger online demographic watching streaming content and the generally older demographic formerly wedded to afternoon soaps.

Regarding the apparent inconsistency in competing with its parent corporations providing new original content, the New York Times quoted Hulu’s SVP of content, Andy Forssell, as noting that the company would work to “get stuff made and not compete with our partners.”28

As discussed in Chapter 6 regarding TV, and as the trend tilts toward VOD consumption, it is interesting to speculate that there is nothing, in theory, to prevent experiments that launch shows first on Hulu and then window them second to broadcast. In fact, this pattern could be an effective hedge against erosion of certain demographics, where it may be easier to market to audiences whose lives are spent disproportionately online and interacting via social media. Unlike the discussion of development in Chapter 2, where online series can, in cases, be thought of as testing grounds for pilots and series that may then leap the divide to broadcast, if Hulu’s original fare becomes successful, then classic TV may truly become a syndication/downstream window rather than the production goal. It is also conceivable that, over time, Hulu could window to itself, offering subscribers to Hulu+ a first viewing opportunity before series then migrate either to its own free platform (AVOD-supported Hulu classic) or to traditional TV (see also later discussion of Hulu+).

In essence, hit content will prime the pump, and where it is then made available next will be driven by the then-available licensing choices; vertically integrated options are apt to influence the outcome when value is attached to brand-building, but will become less a defining factor as businesses mature and those financing content are simply focused on what option provides the greatest immediate return. We are a long way from lawsuits alleging one arm of a company such as Hulu has favored its sister service, but like lawsuits which challenge that conglomerates preferentially license properties to their affilaites (e.g., Time Warner licensing movies to HBO or Turner, where producers question whether the licenses are arms-length or higher fees could have been earned by licensing to a competitor), it is only a matter of time before we see the same arguments relating to online services (see Chapter 10 for a discussion of profits and such issues).

Amazon

Amazon, too, joined the group of streaming pioneers to announce its move into original programming. For its part, though, Amazon created a hybrid model not dissimilar to the crowdsourcing schemes discussed in Chapter 3 regarding financing production. Amazon announced that it would be soliciting ideas for comedy and children’s TV programming: anyone can submit a proposal (e.g., pilot script), and, if accepted, Amazon will fund and produce the series, pay the submitter of the “winning” idea $55,000 plus royalties, and distribute the program via its online video service.29

In a sense, this scheme further extends the notion of democratizing content development, as discussed in Chapters 2 and 3 in the context of online access and crowdsourcing vehicles. However, to be fair, Amazon Studios is no less a gatekeeper than a traditional network or studio, with the difference being you do not need a track record, agent, or friend to throw your script into the pool for consideration. In essence, the PR sounds great, but the odds of success are no better—everyone living in LA is pitching something, and Amazon is now simply another buyer, albeit with a new carrot and a bit of a new twist.

What may change the equation, however, is how Amazon claims it will monitor the process. The company initially advised that green-light decisions will be significantly influenced by user feedback when it allows users to watch animatics and video excerpts from proposed shows via Amazon Instant Video; nevertheless, it then plans to follow the tried-and-true process of producing pilots before commissioning additional episodes, and will have the overall development process shepherded by executives hailing from the traditional TV world.30 As for the pilots themselves, which are reputed to cost in the range of $1 million each—putting the investment squarely between the lower costs of cable and the higher/closer to $2 million investment by broadcast networks for new comedies31—Amazon users will play a pivotal role in selecting series to go to production. Roy Price, Director of Amazon Studios, outlined the process for the first set of six pilots culled from more than 2,000 submitted ideas: “The six comedy pilots will begin production shortly, and once they are complete, we plan to post the pilots on Amazon Instant Video for feedback. We want Amazon customers to help us decide which original series we should produce.”32 Despite the lure of opening up the process to anyone submitting an idea, and punctuating my statement above that odds of discovery/success are no better than traditional development, the initial batch of pilots—including a scripted comedy show based on the Onion’s newsroom, to a series about four senators from Doonsburry creator/comic-strip legend Gary Trudeau called Alpha House—essentially all come from sources with media credibility/roots.33

Regardless of how one categorizes the odds, the Amazon development process is, at least by some measure, an application of inverting the development pyramid by funneling concepts from the wider user base to the development executive, rather than the development executive selecting the project and then marketing it to the broad customer base (see Figure 2.2, Chapter 2, and the related discussion).

Beyond pure originals, Amazon is taking a page out of its competitors’ playbooks and also licensing content to diversify its portfolio of original offerings. For example, it announced that its Prime Instant Video would become the exclusive online subscription outlet for the PBS hit Downton Abbey.34 Such arrangements (beyond again punctuating the value of the exclusivity driver in Ulin’s Rule) ultimately set the stage for production extensions or joint ventures—theoretically, if viewership on PBS were to wane, then Amazon could step in and continue the show to a targeted online audience, a point discussed and postulated earlier in the context of the promise of online to sustain more limited but targeted viewing (though perhaps this is not the best example, as there may be no more targeted TV audience to begin with than fare for PBS).

Inevitably, Amazon, as well as Netflix, Hulu, and YouTube, will learn the challenge of launching production and development versus the success rate of crafting true and sustainable hits. Netflix in its initial foray (2013) already saw the vicissitudes, having its stock stock beaten up post the launch of Arrested Development, when the show was panned by critics (despite Netflix advising its subscribers consumed the episodes at a rate eclipsing House of Cards),35 and then being hailed, when it garnered fourteen Emmy nominations to become the first streaming service to break the artificial ceiling and be perceived as a “player” in the TV space.36 To the extent these online pioneers succeed, though, it will be a boon for production and significant expansion of creative outlets. In a world with endless niche cable channels, there is always room for quality content, and it will be enlightening to see who can crack the formula in the online streaming space and whether this will truly lead to new forms of self-sustaining networks or merely complimentary programming.

Traditional Search Engines and Everyone Else Creating Online Originals

Search Engines

With the major online entertainment providers such as YouTube, Hulu, Netflix, and Crackle (www.crackle.com, owned by Sony) moving into originals, it was not surprising for search engines, who have always wanted to provide diversified news and entertainment content to their user base, to jump on the bandwagon.

Yahoo!, which has been a leader in online news, launched a new Web series hosted by former ABC news anchor Katie Couric. The show, launched in May 2012, called Katie’s Talk, includes interviews with topic experts and will focus on topics such as health, nutrition, parenting, and wellness.37

AOL, for its part, announced a more ambitious program, launching AOL On Network. The “network” takes the video library of content (already accessible via AOL) and themes programming into 14 curated channels, which will be supplemented by an array of original new series. The new series, announced during what AOL dubbed its “2012 Digital Content NewFront”—its spin on crafting new digital upfronts to steal traditional TV’s thunder, and some of its advertising dollars—included seven original shows, spanning scripted entertainment, reality, games, and news.38 Among these shows were:

1. Digital Justice, a weekly reality series tracking digital forensic investigators working to solve cyber crimes;

2. Little Women Big Cars (debuted May 2012), a Web series about soccer moms striving to balance their schedules and family lives; and

3. Nina Garcia, in which Project Runway judge Nina Garcia helps women reclaim their swagger and mojo when they have lost their groove and embarked on a new life-changing phase (e.g., just had a new baby, stared a new relationship).39

Independents and Studios

The ever-maturing online video advertising market is increasingly enabling original programming made for the Web—producers now able to rely on more revenues than simply from integrated product placements (see Chapters 2 and 3) are developing shows with the Internet as the end and only outlet. The number of players and variety is increasing, and while slowly to date it will be interesting to see if the push into original content by online aggregators will stimulate the whole market, and if we will see renewed interest from traditional media sources that have so far only dabbled in the area. Sony produced Sofia’s Diary for Bebo, Sony’s Crackle has launched various Web series (e.g., paranormal thriller The Unknown), and Big Brother producer Endemol produced an interactive reality show The Gap Year (also for Bebo). Alongside such majors, new media studios such as Worldwide Biggies (launched by former Viacom executive Albie Hecht, who headed Nickelodeon programming and launched Spike), and Electric Farm Entertainment (whose founders include former CBS Entertainment president and co-head of Sony Pictures Entertainment Jeff Sagansky, along with Lizzie McGuire producer Stan Rogow) are examples of traditional media executives trying to match talent and programming to launch the next generation of online shows.40

Despite these examples, I had anticipated that original online series would have become more vibrant since the publication of my first edition, especially given the improvement in streaming delivery, increase in access points (e.g., tablets), and growth of streamed (and targeted) video advertising. However, as noted in Chapter 2 under the discussion of development, there are scant examples of success; programming has seemed to grow even more niche and, to date, talent guilds’ fears of being cut out of a new pie have proven unfounded, for there is generally not much money being made. Even studios with deep pockets that would seem able to risk development have generally shied away, dabbling at best; Disney’s Stage 9, which was touted as a dedicated made-for-the-web production arm, launched a couple of short-lived properties (e.g., The Squeegees), and is symptomatic, as it was basically shuttered and folded back into the studio after less than a couple of years. Over time, though, there is little doubt that more, and better, online original content will be produced. In fact, as discussed in the context of key aggregators (e.g., Netflix, Amazon, YouTube, Hulu), this is now finally happening on a much grander scale—what we have not seen yet is crossover or hits, with online series still somewhat novelties. Nevertheless, with the amounts being invested and the ability of these deep-pocketed leaders to market and leverage the one-to-one relationships they enjoy with their bases, it is inevitable that something will break through—the issue is timing, and whether these companies have the fortitude to withstand the “nobody knows anything” risk to see through portfolios and become the next evolution of networks.

Finally, as the market evolves, it will be further interesting to see the impact on windowing. More and niche segmented channels open up opportunities to spin-off or continue programming (that might otherwise not be sustainable) to hyper-targeted audiences, and where a show may debut, migrate, or be viewed in a downstream window opens up a new matrix of licensing possibilities. Again, the notion of “what is TV?” is not easy to define as television morphs into a branding construct and is no longer defined simply by a single platform or appointment viewing.

Cord-Cutting: Over-the-Top, Apps, and Other Modes of Access

Since the days of Web TV (mid 1990s before its purchase by Microsoft), a Holy Grail has been the integration of the Web with television. With the advent of Nexflix’s streaming service, the use of Microsoft’s Xbox as a multimedia content hub (originally XBox 360), and the growth of Roku and Apple TV, the promise of streaming media boxes has largely been fulfilled. In addition to Roku, devices such as offered by Boxee easily enable customers to stream digital content and watch it via a TV or other screen/monitor. I have had the pleasure of watching Roku grow, and meeting with its founder (Anthony Wood) and former president (David Krall) in their Silicon Valley headquarters—for those who have not used Roku, the experience is the definition of plug-and-play. Simply plug the Roku box in, select your home wireless network, and you have VOD access to streaming content such as Amazon VOD and Netflix, with full DVR control functionality (e.g., pause). When Roku invested heavily in advertising during the 2011 holiday season, brought down the price of its base box to $50, and had the hardware carried in mass-market electronic outlets, the brand began transitioning to mainstream use.41 With a Roku box and other OTT devices, the virtual video store is truly realized, with inventory potentially dwarfing a retail outlet at your fingertips, loading and playing instantly.

I do not plan to offer a comparison of various devices here—there are plenty of online sources that can compare feature sets among competitive boxes. Rather, I simply want to emphasize general capability of the devices that enable the Internet-to-TV junction. I have also focused on Roku and Boxee here, not because of favoritism, but simply to illustrate the marketplace. Unless you are living in a cave, you know about Google and Apple, brands that permeate daily life and have changed the face of media. Roku and Boxee, though, are specialized companies focusing exclusively on this space; accordingly, they have either pioneered designs or user interfaces that cater to the core elements of easily porting content digitally/online to the TV screen, and are also likely more recognized by tech-savvy consumers (though you may hear more about Boxee, as it was acquired by Samsung in summer 2013).42

In the instance of both Boxee and Roku, both products are truly hardware/integrated software products that are, at least in design, content-agnostic; each box pulls content digitally and uses the TV merely as a display monitor, linking content from Web-based sources, as opposed to a TV that sources its content from the airwaves, cable, or satellite. Accordingly, both boxes allow users to pull movie and TV content from aggregators (e.g., Netflix, Vudu), and apps from the Web (e.g., Pandora, Flickr). In an effort to expand the content able to be pulled in, Boxee added an HD antenna to access live TV (grabbing the free digital signals of the major networks, and thus capturing a good chunk of live sports programming). The HD antenna connects directly to a small USB thumb drive that plugs into the Boxee device. (Note: Subtle legal differences in implementation have not made it the same target, to date, as Aero discussed in Chapter 2.) This represents the very definition of cord-cutting. While its marketing pitch in 2012 became “watch on TV, watch on apps” (to watch on TV, the company highlights that you either need the antenna or a cable connection), earlier website headings under live TV brazenly noted: “Broadcast + Internet = Easy Alternative to Cable.” Boxee’s website even advised: “Boxee intelligently blends live broadcast TV with shows and movies from the Internet to give you one interface for everything you want to watch … Boxee provides an easy alternative to high-priced monthly cable bills.”43 You can almost hear whispers of “snip, snip.”

Finally, because the Boxee box/platform is content-agnostic and relies on software as “the brain,” the box enables users to sort and interact with the content in the same way that users are manipulating connectivity on the Web. Accordingly, watching can become social, recommendations can come from friends and not just a cycling (and curated) TV guide channel, and content listings and queues can be personalized. (Note: In parallel to its connected TV product, Boxee used to offer a software download, enabling the same functionality via personal computers. In 2012, however, the company ceased supporting its software downloads, with its VP Marketing noting in a blog post: “We believe the future of TV will be driven by devices such as the Boxee box, connected TVs/Blu-rays and second-screen devices such as tablets and phones … People will continue to watch a lot of video on their computer, but it is more likely to be a laptop than a home-theater PC and probably through a browser rather than downloaded software.”44

When one thinks about the scope of what these new boxes enable, from the realization of the virtual video store to sorting and searching UI applications that more resemble a computer than a TV, there is a tendency to declare the future is here and that everyone will soon own a box. Remembering, though, the maxim content is king and that it is incredibly challenging to convince the mass-market user base to adopt yet another device that plugs in, means that the battle is far from over. In fact, I believe that despite the elegance and leap forward these boxes represent, by my next edition they could be viewed as iterative steps in the wasteland of media distribution. Why? Because the technology will have been integrated as a feature set into something else most already have: the TV. TiVo was revolutionary, but its core (and at the time revolutionary) application of pausing and recording live TV is now bundled into every DVR and cable box. Similarly, the enabling features of these best-of-breed hardware boxes will be integrated directly into TVs, or other devices connecting the living room (see the discussion under “Living Room Convergence”)—the very fact that Boxee had the capability of being downloaded as software (regardless of the fact the company elected to abandon supporting PC downloads) implicates this slippery slope.

This migration was further highlighted to me in the summer of 2012, when I moved to Europe—instead of the “plug in” being my Roku box, sourcing and translating my wireless Internet signal, I plugged in a mini-receiver to the USB port in my Internet-ready TV, making my TV the multimedia entry point to the Internet, with key channels such as YouTube already preprogrammed.

In summer 2013, Google launched a variant to this gizmo with its Chromecast thumbdrive that plugs into a TV’s HDMI port; in essence, Chromecast allows the user to search video on the Web via a mobile/portable device or laptop, and then stream that content over the TV monitor.45 To a degree, it reduces the OTT box to its barest form and defines plug and play.

In the chicken-and-egg conundrum of whether it is better to gain access to Web and app-based content via a plug in to the TV or instead gain access to TV by a plug in to a Web-based box, there is likely to be no absolute answer—it is hard to imagine the elimination of TVs, and yet cord-cutting is real and there will be a significant group that will prefer no cable bills and be watching content via over-the-air channels and the vast array of app-based programming available.

Again, if you believe content is king, and looking at the renaissance of high-quality TV being produced by cable as discussed in Chapter 6, strong originals will provide a buffer against cord-cutting; if, however, those originals are coming from online sources (as discussed above in the context of aggregators introducing originals), then that may further bolster cord-cutting. The consumer may save here, but there is unlikely to be a free lunch, as those same services are apt to erect barriers, such as offering content via subscription pay, to differentiate themselves—going back to Ulin’s Rule, there need to be certain barriers (e.g., windows) to monetize content, and free access plus free content, even if AVOD proves more successful, is unlikely to sustain the production budgets, enabling high-quality premium content that so many people crave. Content will not be king in a cord-cutting world that does not figure out a way to enable value drivers to fund quality programming.

Multipurpose Boxes—Living Room Convergence and Home Network Hubs

The ability to access video over the Internet and then watch it over your TV has been perceived by many as the ultimate goal, and the premise of “living room convergence.” At some level, convergence of platforms and content access would subsume all the different paths discussed in this chapter; accordingly, in my original edition, I was unsure whether to discuss Apple TV and other hybrid boxes under general market convergence, or rather in the context of download threats to the DVD market. Two facts now seem clear: convergence enabling simultaneous on-demand access to both online and offline content will continue, but the aggregation of access into one device is not likely to occur. Think more about access to TV and film content along the same lines as access to any content available on the Web: in a connected world, the ability to browse for what we want will become hardware-agnostic, and hardware will integrate flexible applications. It is no longer about playing a game or accessing TV via only one device, but about having access to Hulu, Netflix, Facebook, HBO, etc. via whatever device you may want to use, be that a TV, tablet, phone, or game console.

The advantage that devices that already connect to the TV have is just that: the TV monitor screen is still the best display medium, given size and integrated audio output. Apple’s Apple TV may not have been the “killer app” people wanted, but regardless of the reason (e.g., people did not want another box), it was only one among a number of hardware solutions trying to provide the bridge. In a sense, it had been tried before (again, remember Web TV?), and whether the bridge is a new box or a feature in an existing box, in the long run there seems something a bit doomed about trying to create an interface to a television when the next generation of televisions can do it themselves (though innovative devices, bridging the Internet and TV, and enabling customization will undoubtedly drive new markets before such devices become standard integrated TV features, and a monitor is the access point to all).

One notable interface, though, where convergence is manifested today is via integrated games platforms such as Microsoft’s Xbox Live Arcade (XBLA) and Sony’s PlayStation Network (PSN); these systems/environments enable both access to linear content and connectivity to millions playing interactive games. The growth of the Xbox Live platform (boasting more than 40 million members) and PSN (which has over 90 million registered users) and integrated ecosystems demonstrates a compelling application of living room convergence.46 The lineup of content accessible via the Xbox 360 system, as an example, includes Netflix, Vudu, Hulu+, YouTube, HBO Go, and a variety of cable channels. In fact, Microsoft has announced that Xbox Live subscribers actually used the game console more for consuming entertainment than actual gaming—with Adweek quoting Microsoft’s SVP of interactive entertainment as noting 18 billion hours of entertainment were consumed in 2012 by the service’s more than 46 million subscribers.47

Not surprisingly, given this base and trend, and taking note of other online leaders launching original content, Microsoft too is augmenting its suite of offerings by producing original programming. In 2012, it hired former president of CBS Network Television Entertainment Group, Nancy Tellem, to become President of Microsoft’s entertainment and digital media unit. A range of product is being considered, from high-quality pay-level content, to reality, series, alternative, and live programming (with how such product is monetized, such as potential add-on pricing to existing subscription costs, open to a variety of business models). Further, and talking about the possibility of transmedia applications and secondary storylines on second-screen devices, Adweek noted from an interview with Tellem that: “She saw episodes ranging from as short as 10 minutes to an hour and a half, multiple episodes being produced, and using Xbox’s interactive capabilities, be it the voice-and-gesture-enabled Kinect or the second-screen SmartGlass app.”48

Original content aside, back to the box, the question Microsoft asks, rightly so, is: Why buy a limited feature box such as Roku when you can get the same content on the Xbox you already have? In terms of streaming and access, they are, in fact, comparable; the difference then lies in cost, user interface, space, and all the other features that drive a consumer to prefer one product over another. In terms of the question “Is living room convergence possible, and is it here?” the answer is yes; the question now becomes “What box/device do people want and, in terms of adoption, how many will they have?” Further, the question becomes one of “How many devices do you need (e.g., multiple TVs), and does the connection need to be fixed or can it be portable? Assuming your next TV has Bluetooth capability (or something similar), if an application such as Boxee software integrated into your tablet can be paired with your TV, enabling your tablet (or even cell phone) to act as your remote control, would that be enough? To some, yes; to the person also frequently connected to a gaming console, probably not; and to the definitive couch potato wedded to their remote, maybe somewhere inbetween. This last example, though, may be moot when the box itself is actually part of your TV.

Integrated Televisions: Internet Access Embedded within Your TV

In terms of television, for several years new sets were being conceived and built with enabling chips, such as evidenced by a deal announced in the summer of 2008 between Amazon and Sony. The then-named Amazon Video-on-Demand video store was placed on new high-definition Sony Bravia televisions. Today, there are multiple manufacturers making Internet-ready TVs, which, unlike boxes that connect via a video cable (e.g., HDMI cable), enable direct Internet access the same way your computer would connect (i.e., wirelessly, through a built-in port, antenna, or via an Ethernet cable). Once the Internet connectivity is established, then content is accessible via apps—Netflix, for example, is an app available on Samsung, Vizio, and Sony Internet televisions.

The limitation to most of the TVs will prove not to be the technology (the ability to access the Internet, and all the content that this implies, over your TV will become commonplace). Rather, the defining feature will become the user interface; complicated remote controls became the bane of the VCR industry—Roku succeeded, in part, because of the simplicity of its remote (minimal buttons and as easy as the plug-and-play hookup), and Apple redefined phones and tablets with its touch screen. Many were hoping that the original Apple TV would have created such a quantum leap, but a few years forward and most internet TVs are still controlled by complicated remotes or keyboards. Whether the next iteration brings touch screens, voice-activated controls (akin to Apple’s Siri), or an entirely new approach, there is no doubt that TV manufactures will focus on pushing convergence and eliminating a box whose features it can seamlessly integrate.

Home Network Hubs and Multi-Screen Access—TV as the Tip of the Iceberg

Once apps and Internet functionality can be embedded into a television, then the next logical question is: Why stop there? If TVs in a networked and multi-screen world become just another type of monitor (though clearly the best one, given size, resolution, and audio), then it should be possible that the “junction box” can become more robust than anything we can imagine today. The future is likely to change the complexion of digital access in home to networked hubs. Whether Internet comes into your home via a high-speed phone connection or cable, the connection to a “box” is more apt to become a nerve center running a myriad of applications.

The first and most obvious iteration will be to enable TV Everywhere solutions within the wireless footprint of your home. We are already seeing this with applications such as AT&T U-verse, where content can move from one TV screen to another with linked DVR functionality; start a movie in the living room, get tired, and move to finish it in the bedroom. More than that, U-verse now allows the downloading of mobile apps to smartphones, where the consumer can browse TV guide listings, program his or her DVR, and even download content from his or her subscription packages to whatever device he or she wants. A content provider that already has rights to bring programming into the home is also in a better position (theoretically) to extend those licenses out via its hub, making the same content available via whatever device a customer may want to use for access (e.g., tablet, computer, smartphone) rather than being limited merely to the TV.

Once this capability is routine, then there is no limit to what digital applications may be enabled. Theoretically, anything that needs to be programmed or controlled could be linked via remote control smart access. Whereas iTunes is an integrated ecosystem for managing media, with content able to be stored and accessed via the cloud, why could it not run apps for other elements of your living room, or home overall? Whether turning on or off a burglar alarm, lights, checking sensors in your kitchen, turning up the heat, or even tuning into a nanny cam, a hub tapping into the Internet and enabling remote or localized digital control is not a far-fetched notion. It will be media applications that first create the experience, but the digital remote control will then migrate to manage your entire connected home and life.

Figure 7.3

© 2013 Apple, Inc.

Figure 7.4

© 2013 Apple, Inc.

Third Screen: Smartphones as Hub, Even if Not Generally Categorized as “Over the Top”

Smartphones have been hailed as the next great distribution platform, and are commonly referred to as the “third screen.” In my first edition, I posed the question: Why would a consumer need unique access to content through its mobile carrier versus gaining access to the same content via the Internet (which is accessible via its phone)? The answer, at that time, was that mobile carriers were trying to carve out a piece of the pie and provide a unique offering, and in some cases partnering to co-brand portals and gateways. Access was via a branded icon, which, if it did not require a download, would come bundled with the phone—“on deck.” The introduction of the iPhone and the emergence of an app ecosystem have fundamentally changed the workings of this market. Apps, whether on tablets or smartphones, are becoming ubiquitous, and content providers are enabling direct access, such as via HBO Go. With the advent of the iPhone and explosion of the smartphone market, phones are, to put it simply, no longer mere phones. (Note: Neither Google’s Android phones nor iPhones existed when the first version of this book was released, just a handful of years ago.) Instead, they are mini-digital hubs, a kind of home network on the go. A phone today can be a super remote control, programming and managing a local screen (i.e., your TV), a screen of its own (such as accessing content via iTunes or Hulu, or even live feeds) for watching content, and a personal computer, allowing you to surf the Web via a browser and then directly link to content (see Figures 7.3 and 7.4).

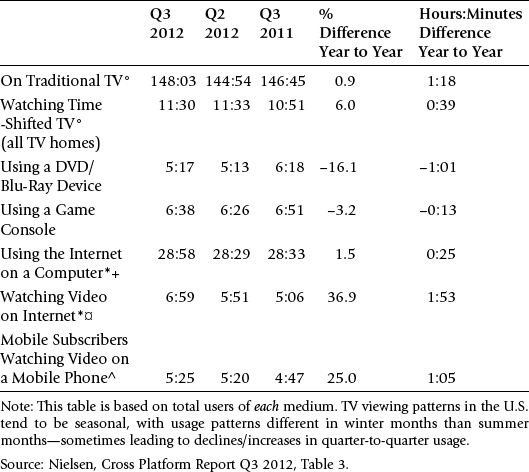

The potential for this market is just being realized. According to Nielsen’s Three-Screen Report, comparing television, Internet, and mobile viewing, as of the beginning of 2008 there were more than 90 million mobile subscribers who owned video-capable phones (representing 36 percent of all U.S. mobile subscribers) and nearly 14 million people were paying for a mobile video plan (only a 6 percent penetration of mobile subscribers).49 By 2012, the number of people watching on phones roughly doubled, with Nielsen reporting (though admittedly not a pure apples-to-apples comparison) that more than 33 million mobile phone owners watch video on their phones.50

Tablets and the New Multi-Screen World: Going Beyond the Notion of Second and Third Screen

Tablets have so quickly become part of the landscape, and as a hybrid between a laptop and a portable device offering the advantages of apps first found on smartphones, that the category has become the device of choice for watching content on the go. In fact, the versatility of tablets is such that the NPD Group forecast in 2013 that tablet PCs shipped would exceed notebook computer PCs for the first time.51

Like the trend innovated by Apple with the iPhone, the iPad was a brainchild of Steve Jobs and further cemented his already iconic status. While the iPad, and tablets in general, are attractive for a myriad of reasons, consuming video content is among their most compelling features—so much so that its screen is more important than the phone, and now underpins the concept of multi-screen access. The Kindle Fire complements Amazon’s VOD and download options, with a harmonized ecosystem that rivals Apple’s. Although at the time Amazon did not reveal public numbers, various analysts estimate the U.S. installed base to exceed 12.5 million units by the first quarter of 2013 (through two holiday seasons of sales), making it the most prominent Android-based tablet. In fact, Venture Beat ran an article estimating that the Kindle Fire’s penetration had a reached a point whereby each tablet only needed to generate $3 per month in digital sales to yield a material profit.52

To fulfil consumer demand and expectations, every content distributor today has to find a way to seamlessly deliver to the multi-screen world, which now counts TV monitors (directly or via OTT services and STBs), PCs, tablets, smartphones, and game consoles. In just the tablet arena, this is a technically complex endeavor, given the growing variety of brand manufacturers, competing closed ecosystems (e.g., Amazon, Apple), and rival operating systems (e.g., Microsoft Windows, Google’s Android, Apple’s iOS).

Compare this to the environment not so long ago (depicted in Figure 6.2 in Chapter 6 where just TV and VCR are below the line), and it becomes a truism to say distribution today has become more complex. To producers and broadcasters, who are generally agnostic as to device, the opportunity for reach and making content ubiquitously accessible is groundbreaking. At the same time, though, this ubiquity is fraught with monetization challenges, as underscored by Ulin’s Rule, and multi-screen access, no more than online access, does not guarantee increased profitability.

Growth of the App Economy—Access via Tablets and Smartphones

An entire book could be written about the explosion of the app economy and the phenomenon of tablets, and I do not plan to delve into the history and specifics of each of these categories. Nevertheless, a discussion of media access and distribution would not be complete without noting the impact.

The whole notion of “apps” was created when Apple launched its App Store in 2008, dramatically expanding the functionality of the iPhone—a classic example of utilizing software to drive hardware sales, though in this example profits flourished in tandem. The market adoption was nothing short of extraordinary, both in terms of companies leveraging the opportunity to develop apps, launching everything from new content to new businesses. Only nine months after the store’s launch, Apple’s SVP of worldwide product marketing announced in a press release: “The revolutionary App Store has been a phenomenal hit with iPhone and iPod touch users around the world, and we’d like to thank our customers and developers for helping us achieve the astonishing milestone of one billion apps downloaded.”53 By the start of 2013, in another press release, Apple recounted the following new milestones:

■ Customers have downloaded over 40 billion apps, including nearly 20 billion in 2012 alone.

■ The App Store has over 500 million active accounts.

■ The third-party developer community have created more than 775,000 apps across the iPhone, iPad, and iPod touch.

■ Since inception of the App Store, developers have been paid over $7 billion by Apple.