Studios and Networks as Venture Capitalists

This chapter will discuss how film and television projects are financed, including how the money is raised and secured and what piece of the pie parties retain for their investment. I will argue that, to a large degree, Hollywood studios are simply specialized venture capitalists with the return on investment (ROI) strategy premised on limited but large bets. The discussion of traditional film and TV financing is in stark contrast to original Internet production, which today remains heavily dependent on venture capital or other private backing, given the nascent (though growing) video advertising market and speculative returns; with the advent of online leaders moving into original production (see Chapter 7), though, these differences are likely to narrow, and, on the assumption that online “networks” such as Netflix find success and compete more directly with traditional TV channels, then inevitably there will be a measure of convergence.

Standard Hollywood movies have become extraordinarily expensive: the average cost of a studio-released film is now roughly $70 million, and when then adding marketing and distribution costs, the sunk cost per project typically exceeds $100 million1 (see Table 9.5 in Chapter 9). Moreover, all studios have a certain number of event or “tentpole” pictures per year whose total production and marketing costs will be well in excess of $100 million. In fact, as highlighted in Chapter 1, certain pictures can even have budgets exceeding $200 million. In 2005, Universal’s King Kong, directed by Peter Jackson, was reported to have a budget of $207 million.2 In 2006, Variety reported Superman Returns from Warner Bros. passed $200 million as well. By 2007, multiple pictures (e.g., Spider-Man 3, Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End) were reputedly cresting this mark.3 By 2012, exceeding the $200 million mark was no longer unusual, with the following movies all reputed to be in this range: John Carter, The Dark Knight Rises, The Avengers, Battleship, The Amazing Spider-Man, and Men in Black 3.4 Perhaps this level, though, represents the limit that studios can bear (especially with declining DVD revenues), for even Avatar was reputed to cost in the $230 million range (though, when combining marketing, the total production and marketing costs were estimated at more than $380 million).5

TV financing costs are tempered by the ability to stage commitments (e.g., pilot, episode commitment by season), and while the risks are therefore smaller, the numbers for network shows and movie-like pay TV series (e.g., The Sopranos, Rome, Game of Thrones) can nevertheless be in the tens of millions across a season.

Principal Methods of Financing Films

As with any other business, there are innumerable ways of financing the production and release of a film. The following is a snapshot of the most common financing schemes, with each category discussed in detail later in this chapter.

The first, and perhaps oldest, method to fund production is via studio financing, where a major studio simply foots the bill itself. Even when a studio pays, however, there are often issues about how it raises the money and whether it reduces the risk by syndicating a portion of the financing or selling off parts. A second form of financing involves schemes pursuant to which independent producers secure capital either to co-finance or fully fund a picture; this can involve bank financing, pre-sales, completion bonds, negative pickup structures, and complicated debt and equity slate financings.

Another scenario employed by independent producers, though limited to a subset of extremely wealthy and powerful producers (and, as a corollary, successful), is simply to shoulder all the risk and self-finance pictures. This is the scenario sometimes referred to as a distribution rental model, such as the deal between Lucasfilm and Fox for the Star Wars prequels (The Phantom Menace, Attack of the Clones, and Revenge of the Sith), the much-speculated-about deal between Pixar and Disney (before Disney acquired Pixar in 2006), and allegedly, DreamWorks’ relationship with Disney.

Finally, in an apt analogy to the venture capital world, productions can sometimes have “angel” financing, where a wealthy third-party entity or individual may simply underwrite a production. This was the case with Robert Zemeckis’ Polar Express, which, as discussed in more detail later, was significantly underwritten by real estate mogul Steve Bing.

A level of complexity is introduced in most financings because the structure is rarely a pure form of the methods previously described. Coproductions, for example, are a common vehicle to share risk, and can take place within any one of the structures; moreover, the term coproduction itself is much ballyhooed and little understood. It can mean anything from a sharing of rights to a legal structure tied to formal government subsidies and tax schemes.

Principal Methods of Financing Online Production

There is not much to summarize in this area because there are no well-developed models in the online space akin to film and TV. Today, the principal method of financing online production is to secure funding from friends and family or venture capitalists (VCs) willing to advance funds against a stake in the website/production company. Very few companies are breaking even in this space, and the VCs are frequently betting on building up sites and “mini-channels” rather than focusing on funding a specific individual piece of content. Sites such as funny ordie.com (Will Ferrell and Sequoia Capital-backed) and comedy.com (Dean Valentine, former Prexy UPN) are seemingly content aggregation plays that likely rest on the strategy that the brand/site will be worth more than the sum of its parts. Accordingly, we can surmise that the goal, as with all VC-type investments, is an IPO or sale based on future multiples rather than value based on a piece of content’s current cash flow. The online space is better understood if one views the space as a clear playing field in which entrepreneurs are launching hundreds of new networks, each vying for reach and brand adoption.

Another strategy—though less popular today than a few years ago, which speaks volumes in itself regarding what networks think about the threat to their series from short-form originals—is for the larger media groups to fund online sister divisions, attempting to incubate new content that may create crossover synergies, as well as developing self-sustaining niche channels and hits. Funding for shows in affiliated divisions is advanced by the larger company and then recouped by revenues garnered through advertising, sponsorships, and product placements (see also Chapter 9 for a discussion of product placements versus promotional partners).

It is product placements, though, that appear to be the most sought-after method to, in part, finance shows and mitigate risk. Often credited as helping to launch the trend, UK site Bebo’s Kate Modern, for example, secured upfront funding via embedded product placements (e.g., character wears a particular shoe brand) and sponsorships; sponsors included Microsoft, Procter & Gamble, Warner Music, Paramount, and Orange. The UK’s Guardian reported that these sponsors each paid up to £250,000 for placement in the show, with each sponsor paying “…based on the amount its brand is integrated into the storyline, which includes monitoring the number of times it appears in the video and is mentioned in the script.”6 More recently, the original Web series Dating Rules (Figure 3.1) integrated products from Ford (Ford Escape car) and Schick (Quattro razor for women) into its second season, which debuted on Hulu in August 2012 (after a successful launch of the sixto eight-minute episodic web series at the beginning of January 2012).

While product placements can be lucrative, the downsides are the risk of dating the show (as a brand may change or be phased out over time), the challenge of compromising the creative to integrate the brand, and the need to lock the advertising far in advance, given production timelines. Moreover, rather than being innovative, the focus on product placements smacks of back-to-the-future thinking, as it was “soaps” that backed TV in the early days; if the analogy holds true, then product placements should give way to more traditional forms of advertising as the market matures (which is now happening, albeit more slowly than many predicted).

Figure 3.1

Not only are traditional “commercials” becoming commonplace online, with video advertising commanding significantly higher CPMs than display ads (and the very presence of these ads making online programming feel more akin to traditional TV) but, for the first time, a landscape exists where original programming can garner direct advertising revenues with the potential of covering production costs—although with a still immature market for online originals, and big players willing to deficit fund productions to bolster and differentiate their brand value, generally only a fraction of the costs are today being recouped (and why even major players are employing hedged strategies as they dip their toes into the challenge of producing and monetizing original programming). As video ads become accepted, and views are expanded by syndicating content offsite to capture more eyeballs (i.e., producers do not care if you watch the show on their site or Hulu, as long as they capture a material share of video ad revenues wherever you watch), then online revenues will increase and the overall experience/business will come to parallel traditional TV. As discussed in Chapter 7, this is already starting to occur, with Hulu, Netflix, Amazon, and YouTube all launching original production, and trying to siphon off advertising dollars from traditional TV via “digital upfronts.” The question will be, then, one of ratings, with metrics tied to views, impressions, and engagement (e.g., click-throughs, text messages) versus ratings points, and the strength of content setting market prices for CPM rates.

Currently, however, there appears to be a disconnect between CPM rates for TV and online, with content owners often claiming premium content is undervalued online, while online networks, in contrast, assert that the same content is priced at a premium to offline media. Although this should be a simple comparison, in fact the two positions are difficult to reconcile because the rates are priced independently and each has different advantages and disadvantages. In the case of offline, the “live” effect of programming and its scale in simultaneously reaching a mass audience commands a premium despite the relative inefficiency of targeting a diffuse (even if generally demographically targeted) audience without direct online-like metrics to track delivery. With online, the advertising can focus delivery and virtually track one-to-one relationships that should command a premium; however, online content’s value is diluted relative to offline because the same scale of mass delivery is only reached (if at all) in fragmented impressions over a long period of time (e.g., 10 million people may be reached over a week or month, rather than simultaneously). Accordingly, valuing what advertising rates should be when similar (if not identical) content is delivered online via free streaming versus the rate for free television delivery is not as straight-forward as it may appear.

Arguably, as referenced in Chapter 6, online is more comparable in delivery to TV syndication, and, over time, some convergence in valuation between these markets may emerge. Even then, the parallels are not exact, in that TV syndication tends to be focused on local pricing (as advertising may be sold market by market), while online syndication of premium content on the Web is not only local, but potentially global. In the end, to some degree the analogy between the experiences (which are not identical) is like comparing apples and oranges, while recognizing there are strong correlations (both fruits, both healthy), as well as differentiating nuances (green and red apples, mandarin oranges). With all these moving parts, it is not surprising that producers of original online content struggle to build monetization models against budgets and initially launched shows with the relative certainty of sponsorships driven by product placements.

When writing my first edition, I asked Jayant Kadambi, founder and CEO of YuMe networks, one of the top online advertising platforms and networks, and a leader in the video advertising space, whether he thought we would soon see convergence between online and offline pricing, or whether the markets would continue to set rates independently. He advised:

Providing a comparison or correlation between online media spending and offline media spending will only help increase the scale, reach, and breadth of online advertising. If an offline advertiser spends $100,000 to reach an audience and receives a GRP of 52, then the natural question before the advertiser spends $100,000 online is: What is the GRP equivalent? Think about purchasing an apple in the U.S. for $1. Intuitively, we know whether that is expensive or not. If we spend 400 drachma for an apple in Greece, the immediate reaction is to convert back to USD to see if it is expensive. So, whether there is convergence in the pricing, models between online and offline will eventually be influenced by the net value the advertiser sees in each medium. But there definitely will be correlation models between the two media outlets.

This dichotomy still generally holds true, and the challenge has become exacerbated by the nature of fragmented viewing. How are ratings or value to be captured in a world when viewers are interacting with multiple screens simultaneously? By 2012, Nielsen reported the following simultaneous usage between TV and tablets:

■ At least once per day: 45 percent

■ At least several times per week: 69 percent

■ Never: 12 percent

And what were we doing while also watching TV? According to Nielsen, looking at the general population, we were looking up information, e-mailing, visiting social networks, and not all the time seeking information relating to what we were watching (Table 3.1).

Table 3.1 Activities Engaged in while Watching Television7

Activities |

General Population* (%) |

Checked e-mail site during the program |

61 |

Checked sport score |

34 |

Looked up coupons or deals related to an advertisement I saw on TV |

22 |

Looked up information related to the TV program I was watching |

37 |

Looked up product information for an advertisement I saw on TV |

27 |

Visited a social network site during the program |

47 |

* Tablet owners aged 13 and over.

Other studies point to similar engagement shifts in today’s multiscreen world—the same technology that enables a tangential yet deeper dive into related information (e.g. looking up a brand of clothing character X is wearing, or facts about the author), also allows the viewer to veer off course and engage in wholly unrelated activities (e.g., checking in on Facebook). What then is the value of fragmented engagement?

I talk about this a bit in Chapter 6 regarding television, and pose the same question here: Does it make better sense to measure engagement (an Internet model, where concrete actions such as click-throughs and conversions can be tangibly measured) or reach and frequency (traditional advertising metrics), and if the answer is, to a degree, both, then how is value further parsed knowing that engagement in today’s world means one eye on something else? Again, as discussed in Chapter 6, the advertising world has moved slowly, simply capturing viewing a program at different times (e.g., live and when viewed on a DVR within X days of initial airing), and now faces the more daunting challenge of capturing value when content is consumed well outside the historical “appointment viewing” norm, and instead: (1) over a more extended period (time-shifting at will); (2) over multiple devices; and (3) in the context of multi-screen, simultaneous activity. What should a rating mean in this world, and how long will advertisers and media outlets agree to a standard based on what some claim is anachronistic sampling and varied engagement levels of those that (by the sampling statistics) are assumed to be watching in the first place? Nielsen has announced the marginal step of trying to capture Internet streams connected to TVs in expanding the construct of TV households, while pledging to try to develop ratings data that would further capture viewership on portable platforms (e.g. tablets);8 however, this is merely recognizing the obvious migration of viewing programming “off TV” and does not address the related and equally vital issues of harmonizing value amid systems utilizing varied advertising methods (including none in the case of certain subscription streaming services), allocating value when multiple screens may be simultaneously used, and capturing direct engagement. (See also related discussion in Chapter 6.)

As a premise to discussing financing, it is important to digress into certain economic theories that lurk behind the allocation of risk and the disproportionate importance that marketing has in the media and entertainment business. Film and television are classic experience goods, as distinct from ordinary goods. An experience good is a product that the consumer cannot accurately or fully assess until consuming it, whether that is via watching a film or TV show or reading a book.9 Given the nature of creative goods—that nobody knows what will be a success—and the fact that you cannot really know whether you will like a property until you digest it yourself, it is natural for us to look for signals and references to make better bets before investing our time. These references and signals can come from sources as disparate as award recognition, critics’ picks, and word of mouth (or blogs, a new media form of word of mouth). In the end, we are all searching for a trusted source that improves the odds we will make a good choice. The problem is that a good choice is highly personal, and mapping external sources of information regarding a creative good onto an internal measurement, while having to choose among a dizzying range of product (sometimes referred to as infinite variance) from which we will pick a small sample to spend time with (consume), seems an almost impossible proposition.

The issue is made more complex when one considers that the external signals are imperfect. Statistics show that awards are often poor predictors of commercial success, with trends and voting-pool demographics (which the consumer may not share) skewing results. One only needs to look at the disconnect recently between Best Picture Oscar nominations and commercial success to see the pattern. Of the top 15 box office films of 2008, including the top five, The Dark Knight, Iron Man, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, Hancock, and Wall·E, none were nominated for Best Picture (though this comparison, to be fair, should exclude Wall·E, which won for Best Animated Feature; note, I am using this older year because the example comes from before the Academy expanded the nominations for the Best Picture category, in part to combat the fact that few box office hits were being nominated). In fact, of the pictures nominated for Best Picture Oscars in 2008 and 2009, only one picture each year (Juno and The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, respectively) had a United States box office greater than $100 million. The pattern was essentially continued in 2012, with Skyfall, The Dark Knight Rises, and The Avengers all generating greater than $1 billion at the worldwide box office, yet none of the films garnering a Best Picture nomination; in fact, none of the top 15 grossing films worldwide were nominated.10 Perhaps this lack of correlation is a function of the line between movies as an art form versus a commercial endeavor; industry-sponsored awards shows tend to focus on underlying skills and performance attributes, of which subset of inputs are simply another source of signals. When art and entertainment value do overlap, though, such as with a blockbuster that is also a best picture winner, then this may be one of the few cases where signals are clear.

Critics are another source of information, but this information is only as good as your personal mapping to a critic’s choice: How often have we said “I disagree with that opinion,” or were disappointed with a recommendation? Accordingly, we tend to try to adjust the critics’ picks by integrating bias, countering with whether there is a better correlation to types of films they have liked where we agree, etc. Additionally, as also discussed in Chapter 9, it is unclear whether online sources of information that aggregate reviews (e.g., Rotten Tomatoes) and social networking sites that exponentially disseminate opinions actually improve personal decision-making or interject a cacophonous web of biases requiring more sophisticated (or perhaps arbitrary) filtering. Even affinity for actors might pique interest, but it does not help that much (even your favorite actors can be in a clunker).

Finally, word of mouth is the mother of all external signals, and it is the watercooler buzz and positive recommendations that marketers so covet. The danger here is that trends follow herd behavior, and experience goods inherently lend themselves to bandwagon and cascade effects. This is because even with imperfect information (needing to consume the good yourself to really know if you agree with the pack/like it), consumers have to balance internal and external inputs without knowing which judgment is correct. Richard Caves illuminates the problem by what almost seems like a riddle. If you see John buying good X, and you have an independent sense you will like X, you will follow your hunch and go with the flow (and the same pattern holds in reverse with rejection). But what happens if your internal sense differs from the external recommendation and the signals cross each other out? What do you do? If we were to assume the outcome is determined by a coin flip, it can start a trend—if heads you buy, then you agree with John, and the next consumer will see two positive signals, even though in reality there was only one. The problem cascades such that a trend can appear even though the sum of the individual collective gut picks may come out the other way.11 This helps explain, at least in part, how it is easy to wonder how everyone loved or hated such and such, and yet you felt just the opposite coming out of the theater.

It would be an interesting research exercise to study whether social networking sites materially improve signalling. If recommendations are coming from a trusted set of friends, and you have mapped your “likes” onto recommendations, should these external signals trump your internal hunches if not in alignment? Clearly, this is the message social networking sites such as Facebook want its users to accept. The problem is that the information is still imperfect, and the variables that go into whether you ultimately like show X or movie Y are highly subjective and personal—likely influenced by the best external signals you can find, but sill not fully determined by them. This is simply the inherent challenge of experience goods, and while social networks no doubt improve signals (which is unquestionably valuable), they cannot, in and of themselves, defeat the experience good problem.

Combining the factors of information cascades, infinite variance, experience goods, and imperfect signals, it is no wonder that success of product is highly variable, risk is extreme, and that assorted financing schemes have evolved to try to combat the problem. In trying to solve the question whether there are strategies that may temper the risk inherent with movies, and sampling over 2,000 films, economists Arthur de Vany and David Walls concluded that box office revenues have infinite variance and that they do not converge on an average because the mean is dominated by extreme successes (blockbusters). As far as mitigating risk, they conclude it is impossible:

We conclude that the studio model of risk management lacks a foundation in theory or evidence. Revenue forecasts have zero precision, which is just a formal way of saying that “anything can happen.” Movies are complex products and the cascade of information among filmgoers during the course of a film’s theatrical exhibition can evolve along so many paths that it is impossible to attribute the success of a movie to individual causal factors. In other words, as Goldman said, “Nobody knows anything.”12

It is because risk cannot be fully mitigated that participants (studios, producers) have evolved varying financing mechanisms as a way of distributing that risk. I will also argue in Chapter 9 that the nature of experience goods underlies the importance of marketing, which can help signaling and at least try to influence a positive cascade of information.

Challenge Exacerbated in Selecting which Product to Produce

The previous section focuses on the process by which consumers grapple with experience goods in making decisions, but the related challenge of financing is to predict that very outcome before the experience good is even made. The ultimate challenge of financing is that someone is asked to judge this creative value proposition at a root sage without adequate inputs to make the decision required. This is a nearly impossible task. Additionally, it helps explain why the development process is so murky, protracted, subject to second-guessing, and littered with projects that “almost got made.”

This quandary is also, in part, why so much emphasis is placed on backing those with successful track records; it is also why some executives continue to seek a repeatable system to implement and become frustrated realizing that, indeed, some development/production elements are formulaic (e.g., plot points and acts in a script, needing conflict and character growth) and yet the formulas do not necessarily lead to success.

Alas, as noted in Chapter 2, there are no golden rules or right answers in selecting creative goods before they are produced to stave off a single bomb or a more cataclysmic result. The combination of intrinsic risk, the increase in the number of films with $200m+ budgets, and the trend for revenues to be front-loaded with ever shorter theatrical runs (see Chapter 4), has even led luminaries like Steven Spielberg and George Lucas to predict the end of the business as we know it. In a panel at USC’s School of Cinema Arts (2013) Spielberg noted: “There’s going to be an implosion where three or four or maybe even a half dozen mega-budget movies are going to go crashing into the ground, and that’s going to change the paradigm.”13 It is the nature of the business, though, that big productions carry big risks, and from Heaven’s Gate (see Chapter 2) to John Carter and The Lone Ranger (2012 and 2013 releases), some are always pointing to “bombs” that in extreme cases could risk the associated studio.14 If experience goods were merely widgets, then an assembly line would work. However, because creative goods are subject to infinite variety, and nobody knows with certainty what will work—especially at the root stage before a project is infused with its creative spark—what is most coveted and compensated is creative talent backers believe will infuse a project with pixie dust.

Classic Production–Financing–Distribution Deal

This is the standard deal where a producer brings a developed picture to a studio and the studio agrees to fund production and marketing costs, as well as distribute the film. The difference between this structure and a pure in-house production is that in an in-house production, the studio has already acquired the property and then simply green-lights the project, engaging a producer on a work-for-hire basis. While a production–financing–distribution (PFD) deal may entail an assignment of the underlying rights to the studio in return for agreeing to move forward, typically the deal starts with an independent producer who has acquired the rights to a property, developed it, attached key talent, and then “sets it up” at the studio. This is also the stage where agents often play a critical role, by specializing in “packaging” talent (and take a packaging fee), such that a studio is presented with a turnkey project ready to produce.

In return for financing production and distribution, the studio typically acquires all copyright and underlying rights in and to the property, as well as worldwide distribution rights in all media in perpetuity. (Note: There may be select guild mandated reservations of rights.) While this may sound extreme, the studio is shouldering all the financial risk and the producer will be making both upfront fees in the budget, as well as have a back-end participation tied to a negotiated profits definition (see Chapter 10). Accordingly, this is the classic risk–reward scenario, where full financing vests the distributor with the upside and ownership.

Studio Financing of Production Slate; Studio Coproductions

Regardless of whether a studio enters into a PFD agreement or some other structure on a particular picture, from a macro standpoint, studios need a strategy to finance their overall production slate. The simplest and oldest method of financing is via bank credit facilities covering a slate of films. Disney, for example, worked with Credit Suisse First Boston (2005) to structure its $500 million Kingdom Fund.15 As the business continues to grow riskier and more complex, however, studios have sought a variety of methods to secure production financing, acknowledging that they need to cede some upside to offset the enormous risks taken. Investors, too, though, are focused on the risks, especially as technology has altered the landscape and DVD revenues (historically a cash cow buffer) have significantly declined (see Chapter 5).

Coproductions

When a studio wants to offset risk, it will often enter into a coproduction relationship with another studio. In such a case, each studio will agree what percentage of the budget it will contribute, and will, in turn, keep certain exclusive distribution rights. The simplest and most frequently used mechanism is to split domestic and foreign rights. On occasion, this scenario arises when the project involves talent tied to different studios (e.g., famous director vs. lead star), and the only way to move forward is sharing.

Sometimes, however, during production a studio will become nervous with escalating costs and decide to limit its risk by selling off a piece. The most famous example of this is the film Titanic. The movie was originally a Fox production, but as costs spiraled and the studio became increasingly nervous (at the time, there was even talk that the whole studio could be in jeopardy if the film bombed, given the investment), Fox elected to sell off part of the film to Paramount. It was rumored that Paramount invested a fixed sum, allowing the picture to be completed, and ended up with a 50 percent share of the picture, even though its investment was ultimately less than 50 percent of the costs. With the film going on to break all box office records, the deal made by then-studio head John Dolgin was regarded as one of the shrewdest of its day.

A more detailed discussion of coproductions follows, but it is discussed here as a financing mechanism by a studio to spread risk or marry talent, as opposed to the later strategy where a coproduction is a necessary vehicle to raise the money for production in the first place. (Note: Studios can also employ the same strategy as discussed in the section “Independent Financing”; namely, selling select rights or markets.

Debt and Equity Financings

Another mechanism by which a studio will finance films is via stock or other equity/debt offerings. Pixar, for example, went public and was able to use its proceeds to co-finance its pictures with Disney. DreamWorks Animation’s public offering similarly allowed it to finance films and secure below-market distribution fees, and ultimately remain independent when its parent, DreamWorks SKG, was sold to Paramount (December 2005). This is a difficult strategy because: (1) there are off-the-top offering costs that can be significant; and (2) investors are usually looking for a particularly strong track record or brand, which can be hard to illustrate with a diverse studio slate (something that both Pixar and DreamWorks Animation achieved within the niche of computer graphics-based animated films).

Off-Balance Sheet Financing

A mechanism similar to equity financing, in that funds may be raised from a diffuse pool of investors, is a limited partnership. This structure differs, however, in that, as opposed to raising equity capital, it is referred to as off-balance sheet financing. The first and most famous examples were the Disney-backed Silver Screen Limited Partnership offerings in the 1980s.

In 1985, Disney, through broker E.F. Hutton & Company, offered 400,000 limited partnership interests for a maximum offering of $200,000,000. The prospectus, under the use of proceeds section, listed the items shown in Table 3.2 (under the maximum offering scenario).

Amount |

Percentage |

|

Source of funds |

||

Gross offering proceeds |

$200,000,000 |

100 |

Use of funds |

||

Public offering expenses |

||

Selling commissions |

$17,000,000 |

8.5 |

Offering expenses |

$3,500,000 |

1.75 |

Operations |

||

Film financing |

$179,500,000 |

89.75 |

Total use of funds |

$200,000,000 |

100 |

The prospectus footnoted the film financing line as follows:

Funds available for financing films will be loaned pursuant to the Loan Agreement and invested in the Joint Venture to pay film costs, which include direct film cost, overhead payable to Disney and to the Partnership for the benefit of the Managing Partner and a contingency reserve. Disney and the Managing Partner will receive overhead of 13.5 percent and 4 percent, respectively, of the Budgeted Film Cost (excluding overhead) of each Joint Venture Film and 3.75 percent and 1 percent (which is included in the loan amount), respectively, of the direct production costs (plus interest) of the Completed Films …

(Note: The summary reflects the initial offering of $100 million and 200,000 units, which was then amended two months later to double the offering.)

It is an interesting exercise to read through these summary terms, which define distribution fees, requiring Disney’s Buena Vista distribution arm to fund minimum marketing expenditures in releasing each film and allocate revenue disbursement. One item that is both obvious and not obvious (because it is not highlighted) is that the investment is cross-collateralized, given that the unit investments apply to the slate of films rather than to an individual film. As previously noted, this would be difficult to achieve in other instances, but because “Disney” is perceived as a brand and the offering limits the budget range and nature of the pictures, using revenues from multiple films to pay out a single investment can work.

Studios Leveraging Hedge Fund and Private Equity Investments

In the mid 2000s, hedge funds—loosely regulated investment vehicles for wealthy and institutional investors, often requiring a minimum investment of $1 million or more—flush with cash started cozying up to financing opportunities that covered a slate of studio pictures. Beyond simply seeking new investment outlets, another factor potentially driving the new studio–hedge fund (and private equity) partnerships was the quickly changing technology landscape. As release windows started moving, and iPods, DVRs, and the Internet ushered in a new era of digital downloading and access, investors familiar with technology plays were oddly more comfortable investing in the same landscape that was making the control-it-all studios less comfortable with their distribution roots and forecasts. Both were players in high-stakes games, and it was hardly a surprise they should ultimately team up. To the extent studios were already acting like VCs, why should they not play by the same rules as professional VCs and take in private equity groups in a syndicate as partners?

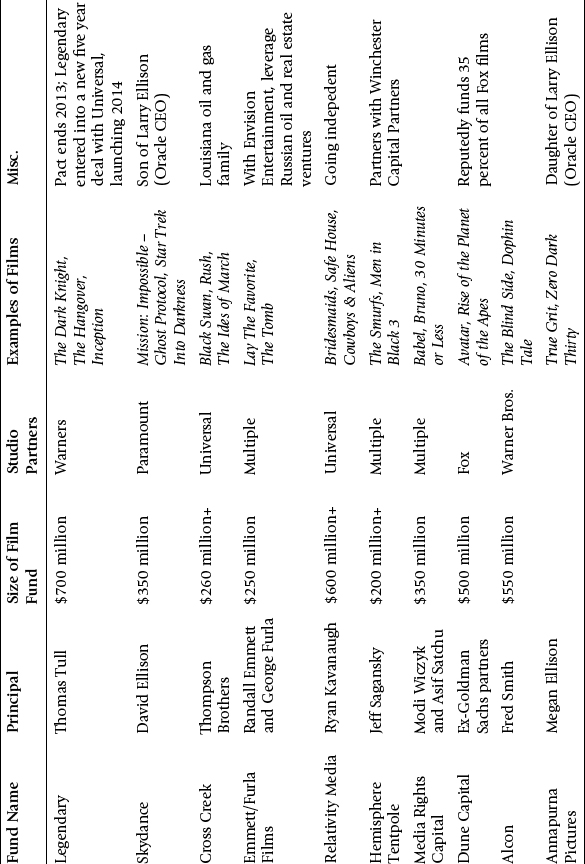

What has changed in the last few years is that there has been a renaissance of outside non-bank film funds. It is difficult to draw bright lines, however, among these funds, in that the line between individuals (“angels”), major private equity-type funds, and independents has become somewhat blurry. I will still discuss each of these variations below, but Table 3.3 is an outline of a sampling of funds (excluding production companies with exclusive studio deals, such as Village Roadshow and New Regency, which could be deemed mini-majors and are discussed separately below, and only including some select examples of funds tied to individual backers that are more generally discussed below under angels).

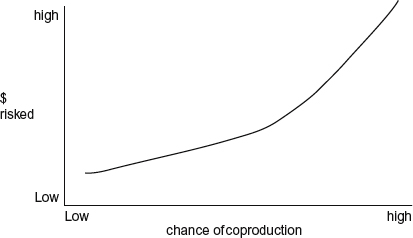

What is interesting about this new range of funds is that there is competition among pioneers of hedge-type funds (Legendary and Relativity), individuals who in today’s culture of billionaires can act as if they were a fund unto themselves (Fred Smith, FedEx founder; offspring of Oracle founder, Larry Ellison), and funds helmed by former studio/network chiefs (Jeff Sagansky and Hemisphere). Moreover, a common evolving thread is that these players are seeking more control, either demanding to have certain approvals over titles, or, once achieving a certain scale, morphing into independent producers masquerading as would-be mini-majors (e.g., Legendary, Relativity). The danger in coming to the table with so much money, and goals of becoming studio-like entities, is that it undermines the inherent concept of funds. At their essence, funds are seeking to employ some hedge strategy, spreading risk across a range of projects, deferring the choice of films to the development experts, and targeting an upside resulting from diversity, balance, and partnership. Hollywood has always been a magnet for “dumb money,” and without a sufficient spread and portfolio there is no objective evidence that this new spigot of investors will prove any more successful than co-financing vehicles of the past. Many of these investments—even if calculated risks—still fall within the ambit of passion-driven financing, and with the concentration of so much wealth by a select few, there is simply a greater pool today of people who can risk greater sums.

Table 3.3 Examples of Funds16

Whether these investors can strike deals that mitigate their risks, in an environment when returns are less predictable because of diminishing home video revenues (see Chapter 5), is pending—clearly investors will try to negotiate prior recoupments, seeking some return before talent is cut in or before the studio takes its fee (see Chapter 10). However, studios have seen it all, and with more competition they will likely hold out for deals that share the upside but avoid cutting into their own safeguards of taking fees off the top (again, see Chapter 10). This is because, while a studio may share 50 percent of the upside with finance partners that correspondingly fund 50 percent of a film’s budget, the most attractive part about these deals is that, historically, they were all about money. This is in stark contrast to the approach of a true mini-major or key production company supplier (e.g., Revolution and Spyglass previously at Sony, Village Roadshow with Warner Bros., and New Regency at Fox), where the independent is taking creative and production control, and even certain distribution rights alongside investments.

Universal’s Prexy-COO Rick Finkelstein noted of the historical hedge fund deals to Variety: “You retain worldwide distribution, you retain complete creative control, you’ve got a financial partner and you’re allowed to take a distribution fee. The economics are quite attractive.”17 Echoing this sentiment, Paramount’s CFO Mark Badagliacca stated: “We like it because it’s a slate deal without giving up any rights.”18

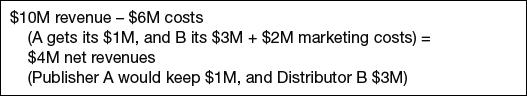

So how do these deals work economically? Although each has its nuances, in the simplest scenario a studio and fund would each share production costs 50/50. In parallel, the studio and fund would similarly share profits 50/50. The issue then became: How are “profits” defined? In this instance, all revenues (except potentially certain ancillaries) would likely be accounted for—namely 100 percent of video revenues as opposed to a 20 percent royalty—and apply in the gross revenue line. In terms of expenses, the studio would usually take a reduced distribution fee (10–15 percent as opposed to 25–30 percent). Also, the studio would often fund print and advertising (P&A) costs and recoup those first, together with its distribution fee, out of gross revenues.

Table 3.4 Batman Begins ROI Example

United States box office |

$205 m |

|

International box office |

$166 m |

|

Total box office |

$371 m |

|

Rentals |

$185 m |

Assume approximately 50 percent theatrical box office |

Video |

$180 m |

Assume approximately $18 net wholesale × 10 million units worldwide |

Net video |

$100 m |

Assume approximately 55 percent margin |

Television |

$65 m |

|

Total revenue |

$350 m |

Rentals + net video + TV |

Production costs |

–$150 m |

$75 million returned to hedge fund (if pre P&A) |

P&A |

–$105 m |

Assume approximately 70 percent production cost |

Distribution fee |

–$52 m |

Assume approximately 15 percent revenues |

Profit |

$43 m |

Revenues – costs (P&A + production + distribution fee) |

Hedge fund |

$21.5 m |

Assume 50 percent share |

Table 3.4 is a simple example, taking the United States and international box office numbers from Batman Begins (box office from www.boxofficemojo.com).

If the fund put in $75 million (50 percent of estimated production costs) and received $21.5 million, that would be a 28.6 percent ROI; if they also had to fund 50 percent of the P&A, however, then the total investment would jump to $127.5 million and their return would drop to 16.8 percent (still high). (Note: These returns do not include leverage effects, where true equity returns would be higher, assuming a mix of equity and debt.) On this logic, the investment would make sense. However, a couple of key items need to be factored in. First, the above is probably a rosy picture, for it assumes no gross players, no interest, etc. Factoring in these costs/expenses, the profit probably dips to single digits (for a detailed discussion of profit calculation, see Chapter 10). Second, this assumes all the revenues come in upfront. In fact, certain TV revenues will come in years downstream, and factoring in the time value of money, the return per year becomes a much smaller amount. Finally, this is one picture, and this hit needs to cover losses on other films: if the return is not more than 20 percent on a hit, then arguably it is going to be difficult to show a return across the portfolio.

Accordingly, the Wall Street Journal quipped in an article titled “Defying the Odds, Hedge Funds Bet Billions on Movies”: “Yet in a business where the conventional wisdom says that 10 percent of a studio’s films are responsible for 100 percent of its profits, even a passel of Harvard Business School graduates may not be immune to the pitfalls faced by nearly every investor to have hit the intersection of Hollywood and Vine.”19 The Wall Street Journal article continued to highlight the limited return on investment, and cash flow issues previously described:

The problem is that under the terms of most co-financing deals, the new investors are often the last in line to get paid. Once exhibitors take their half of ticket sales, many studios take a distribution fee of 10–15 percent of what’s left from the box office. Then, the movie’s production and marketing costs are paid back, and any A-list actors or directors pocket their shares. After that, the revenue-sharing process begins and it continues for the next five or more years as revenue flows in from DVD sales, pay cable showings, and toy or other merchandise sales.20

To Include or Not to Include Tentpoles in the Slate—Do Limited Slates, and the Relatively Small Size of all Slates, Doom Fund Investments?

The studios are obviously quite savvy in the deals they choose, and frequently withhold their perceived best assets from financings that would require a material sharing of upside. It is therefore not surprising that hoped-for tentpoles such as The Chronicles of Narnia and Pirates of the Caribbean series were withheld by Disney from a 2005 co-financing deal, and that Sony excluded Spider-Man 3, the James Bond title Casino Royale, and The Da Vinci Code from its former Gun Hill Road deal.21 (Note: As in most financings, there is more than meets the eye, and it is possible that the Regal Entertainment backing of Narnia and MGM control over James Bond could have forced an “exclusion” because neither of these stakeholders would likely want a further dividing of the pie.) A more recent example was the 2011 negotiation between Warners and Legendary, which limited Legendary’s investment in The Dark Knight Rises to 25 percent from what was reported to be the traditional 50 percent stake in Legendary’s investments in Warner Bros. films. The Los Angeles Times, talking about Warner film group’s president Jeff Robinov’s strategy, noted about the pending Batman sequel: “Because it is expected to be a hugely successful blockbuster—The Dark Knight grossed $1 billion in 2008—Robinov did not want to give away a big piece of the profit …”22

In fact, what is surprising is not the exclusion of major franchise pictures from sharing, but the very fact that certain major tentpoles, such as Batman and Superman (though the franchises had both waned, and the studios were hoping for a comeback) were included in the first place. Their inclusion is what arguably started to attract the most attention in the space.

One could have predicted at the outset, based on simple economic patterns, that this cycle would have to come full circle; namely, hits pay for misses (the above-quoted 10 percent rule), and excluding some of the more likely hits from an overall slate dooms the success of a fund. It took only a short time for the inevitable cycle to start reaching an early maturity.

Poseidon, which reportedly cost $150–160 million to produce, grossed only $22.2 million in its opening weekend, leading to the questioning of Virtual Studio’s strategy and a Variety headline: “Sea Change at Hollywood Newbie: Poseidon Capsizes Fund.”23 Other funds started to fare similarly, with Legendary Pictures-backed (Warners deal) Lady in the Water (M. Night Shyamalan) and Ant Bully (Tom Hanks-backed) underperforming. Quickly, hedge funds were on the defensive, reminding investors about the underlying portfolio strategy.24

But how long would it take for rational economics to right the Poseidon tainted ship? This was not a mutual fund with hundreds of stocks diversifying a risk portfolio; even the largest of the funds was small, with no more than 20–25 pictures in the mix. Nevertheless, the first arguments were focused on differentiating one pool from the next, rather than to address the fact that all the pools were too small to provide a true hedge against risk. Investors, no doubt trying to defend their strategy, first argued that one film did not undermine a portfolio strategy, and then as large films in the portfolio started to underperform, distinguished their pools from others by challenging the scope of the slate. Variety noted: “Wall Streeters said Virtual may be more exposed than the other funds by co-financing such a small slate.”25

Because excluding some of the most likely hits, by definition, increased the risk profile, it was therefore not surprising that funds started to reconsider the composition of portfolios, with the organizer of the Universal and Sony deals with Gun Hill Road going on record that new studio deals would involve a studio’s full slate of pictures.26 No longer would it be so easy for studios to create off-balance sheet financing of $100 million-plus pictures while excluding other key titles.

Of course, a big hit will change all perception, for the amount of money a single film can generate may justify an entire slate investment. Legendary’s share in The Dark Knight, which became the number 2 box office film of all time (at that time), surpassing half a billion in the United States (compare to previous Batman Begins example in Table 3.4) theoretically could have earned it upwards of $250 million over time (and much more if they participate in certain ancillary revenues such as merchandising). Note that the increase in return is more than a linear relationship, because after a certain point additional revenues are not matched by additional costs (i.e., the production and print and initial advertising costs are fixed, so imagine the above Batman Begins example but simply double the revenue lines). It is because a single hit, which may represent less than 5 percent of the total portfolio (based on number of films) can potentially recoup 50 percent or more of an entire fund’s risk that investors tend to ignore the relatively small pool size. Based on statistics, a sample size of 20 may not be large enough to ensure consistent deviations and therefore tempered risk, but one has to remember that these are not random samples, and placing bets with proven producers should positively skew results, as long as all titles are included. A studio will rarely go zero for 10, but as discussed previously, taking some of the best picks out of the mix may change the equation from a predictable statistical spread to more luck-based metrics.

In the merry-go-round of co-financing logic, arguments have now come full circle, as a 2012 Variety article titled “Slate Debate: Investors Now Get to Pick and Choose” noted with respect to some of the current funds discussed above: “In the past, many moneymen blindly financed slates of films they didn’t pick themselves … Now, many co-financing arrangements involve fewer films and allow studio partners like David Ellisons Skydance Productions and Jeff Sagansky’s Hempisphere, for example, to have more leverage in choosing which films to partner on—especially among tentpoles.”27 While ensuring participation in major tentpoles makes sense, the logic of fewer films and selecting those films speaks more toward becoming a producer (high risk) than actually managing a fund (diversified, hedged risk).

Independent financing is a catch-all term that refers to a myriad of financing schemes, and is generally distinguished from the above discussion concerning funds because funds invest across a slate, and much “independent financing” applies on a per-project basis. The common thread is that: (1) money is sought to actually pay for production, requiring that cash is advanced before the project starts; and (2) that the source of funding is, at least in part, from a party other than the distributor. This occurs in two very simple cases: when the producer cannot obtain the studio’s commitment to fund production, or when the producer does not want to take the studio’s money because it can keep something that the studio would have demanded. The “what it keeps” can range from creative control to a larger share of the pie (by bringing money to the table) to retaining specified rights. (Note: While some of the following discussion can apply equally to television (e.g., pre-sales), the bulk of independent financing and the overview below applies in the context of funding films.)

Most cases of independent financing are because the producer needs money to make or complete his or her project. Although there are no bright-line categories, the following are typical methods of financing:

■ foreign pre-sales

■ ancillary advances

■ negative pickups

■ bank credit lines

■ angels

■ crowdsourcing

Although some of these mechanisms, such as pre-sales, are the tools of structuring coproductions, I discuss the nature of coproductions separately below, and here focus on some of the line item issues of how the underlying rights are divided and treated. I have also included crowdsourcing schemes, such as via Kickstarter, which is a relatively new and still evolving source of production financing.

Foreign pre-sales are either full or partial sales of specified rights in a particular territory. For example, it may mean theatrical rights only, or theatrical, video, and TV rights in a territory. These sales can be structured either as percentages of the budget or in fixed dollar terms. Moreover, the deals may be structured on a quitclaim basis (outright sale of rights in perpetuity) or on the basis of an advance, where the producer shares in an upside after the licensee distributor recoups its investment per a negotiated formula. Table 3.5 is a hypothetical example for an animated television show budgeted at $350,000.

Table 3.5 Hypothetical TV Show Finances

Network/Pre-Sale |

Territory and Rights |

Pre-Sold as % Budget |

$ Pre-Sold |

Pan-European broadcaster |

Europe cable |

15 |

52,500 |

French network |

France |

25 |

87,500 |

German network |

Germany |

10 |

35,000 |

UK network |

UK |

5 |

17,500 |

Italian network |

Italy |

5 |

17,500 |

210,000 |

In the above example, if a producer could obtain this level of commitment, it would have 60 percent of its budget secured while still having the balance of the world (United States, Asia, Latin America) available. Depending on the deal structure, the broadcasters may commit to a percentage of budget, rather than a set license fee, which can be advantageous if the budget increases; in fact, in theory only, it is possible to sell more than 100 percent and be in profits before production.

A wrinkle on the above is that not all contributed amounts fall into the same category. Some broadcasters/partners may put in their amount as a straight license fee, others may make contributions contingent on it being a coproduction (requiring a certain amount of localized production/elements and control), and yet others may allocate their contribution between a license fee and an equity investment. To take this example further, the French amount may require a French coproduction, where the government-backed CNC actually contributes an amount and the French broadcaster contributes the balance as its license fee. In this instance, the French network may not demand an equity investment, and may simply acquire broadcast rights since its investment/cost has already been subsidized. The German amount may or may not include an equity component. If the broadcaster demands equity, it could be 50/50, for example, where $17,500 of the $35,000 would be considered an equity investment; namely, they would hold a 5 percent equity stake in the profits. Finally, one partner, such as the Pan-European Broadcaster, may require ancillary rights, or a stake in ancillary rights, as opposed to a stake in the whole. If they were granted European merchandising rights and a fee, then the producer may only have a secondary income stream from merchandising.

There is no obvious outcome, with a continuum of stakeholding moving up and down depending on the percentage of ownership, percentage of budget covered, and range of rights retained/granted by the producer. The final deal may cover enough of the budget to move forward, grant third parties 40–50 percent of the overall equity in defined revenues, and grant others a different percentage of merchandising or video. The endgame is obviously to cover the production budget and retain as much of an equity stake as possible.

I touched on ancillary advances above in pre-sales, but it is important to differentiate between primary and ancillary rights granted. Table 3.5 was predicated on licensing the television broadcast rights to a television show. By ancillary, I mean other downstream revenues, such as from merchandising or video. Because these downstream revenues are dependent on the success of the primary revenue source (e.g., there will likely not be merchandising on an original TV property until it is a hit), these amounts are speculative. Accordingly, these are harder advances to obtain, and will usually be discounted given the uncertain value.

A negative pickup is a deal structure where the distributor guarantees the producer that it will distribute the finished picture and reimburse the producer for agreed negative costs (i.e., production costs), subject to the picture conforming to terms detailed in the negative pickup agreement. With distribution and reimbursement of production costs secured, the producer will then borrow money from a third-party lender using the reimbursement contract as collateral.

The advantage to the distributor is cash flow and the elimination of risk: nothing is paid until the picture is completed to the satisfaction of stipulated contract terms. The advantage to the producer is a greater measure of independence—the terms of the negative pickup agreement will often impose less creative control than if the studio distributor were directly overseeing production—and the elimination of certain financing charges, such as studio interest. (These charges may not be market rate, and may continue to accrue until recoupment, which is set back to the extent distribution fees are taken out first, leaving less cash available to recoup production costs.)

Under a negative pickup structure, the distributor would have approval over all material elements of production. Such approval rights may include approval over the budget, production schedule, the script, all above-the-line talent (i.e., principal cast, director, writer, producer), and contingent compensation granted (e.g., net or gross profit participations). In addition to approval of the creative and financing elements, the agreement will grant the distributor the right to approve delivery specifications. Such specifications will include, for example, that the picture will have a running time of not less than X and not more than Y, and that it will have a rating not more restrictive than “R”.

In both the negative pickup structure and in any structure involving loans from a third party, securing a completion bond will likely be required. A completion bond is a contract with a designated completion bond company that can ultimately take over production and complete the film in the event of a producer default. These companies engage reputable producers, and will monitor the cash flow and progress of production against specified milestones. Of course, all parties will do whatever they can to avoid takeover, but in the draconian eventuality that a producer is failing to deliver, these companies will step in and manage the balance of production. Completion bonds can be quite expensive and are calculated on a percentage of the budget, usually in the range of a few percent. Examples of what may contractually trigger a takeover might include:

■ Over budget: If the picture is materially over budget (e.g., if final estimated direct costs are estimated to exceed the budgeted costs by X, excluding costs of overhead, interest, and the completion bond fee).

■ Over schedule: If the picture is more than X weeks behind schedule.

■ Default: In the event of a material default.

Third-Party Credit—Banks, Angels, and a Mix of Private Equity

Bank Credit Lines

If a producer has a sufficient track record and consistent volume of production, a direct bank credit line may be able to be secured. This will often take the form of a revolving credit facility, and, depending on the structure, may cross-collateralize revenues from pictures to secure the overall facility. The economic advantage to a bank line is that it is all about money. The bank will only be concerned with the financial securitization and recoupment of its loaned sums and will not want to retain rights. Accordingly, this is an advantageous structure to retain the copyright, foreign and ancillary rights, and therefore upside in a property.

It is also possible to structure a bank line as “gap financing,” where only a percentage of the budget is needed. This is a typical scenario where pre-sales and advances against ancillary revenues (such as a merchandising advance from a toy company) cover a significant amount of the production budget, and the bank line covers the bridge or gap to fund 100 percent of the costs. In this instance, the bank line will almost always come in first recoupment position, which gives the lenders comfort. In essence, they can look to 100 percent of the revenues to cover 20 percent of the budget, lowering the risk. Nevertheless, films are inherently risky, and obtaining a bank loan, even if for limited gap financing, is not easy; moreover, the documentation and legal fees can be quite considerable, constituting another expense to be built into the budget.

Mini-Majors and Credit Facilities

Similar to a bank line of credit, producers, directors, and independent studios with a sufficient track record can raise enough money to create a “mini-studio.” This was the case when Joe Roth, former production head at Fox and then Disney, launched Revolution Studios. Combining a variety of distribution output deals, including theatrical distribution via Sony, Revolution raised over $1 billion for film production before a single picture was made. Similarly, when Harvey and Bob Weinstein left Miramax (the company they had founded and sold to Disney), they were able to launch a mini-studio with their new The Weinstein Company—a proposition that was only possible with the combination of distribution deals and significant third-party financing.

To an extent, this is an independent’s dream, and it is common to see a mixture of distribution deals and bank credit facilities funding production (set in place with the security of the distribution arrangements). Another prominent example was Merrill Lynch’s half-billion-dollar backing of Marvel Entertainment, the comic book company whose characters include Spider-Man and X-Men, when it was still an independent (pre acquisition by Disney). (Note: The line between this type of deal and the previously discussed private equity/hedge fund-backed slate financings can be fuzzy; I have separated Marvel here because it was an example of an independent brand raising financing, as opposed to a deal directly leveraging studio distribution.) In May 2006, Merrill Lynch took out a full-page ad in the International Herald Tribune, boasting:

Marvel Entertainment knew that by creating their own film studio they could profit directly from their legendary comic book characters rather than licensing the rights. But they lacked the production facility to achieve their vision. That is, until they talked to Merrill Lynch. We structured a transaction hailed as the “best Hollywood has ever seen,” using Marvel’s intellectual property as equity to raise $525 million—enough to bankroll up to 10 feature films. So now Marvel has full creative control over these characters. Not to mention their own destiny. This is just one example of how Merrill Lynch delivers exceptional financial solutions for exceptional clients.28

Almost 20 years ago, the “mother of all studio financings” at the time was the 1995 creation of DreamWorks SKG. A studio, promising to be on the scale of a major, not just a mini-major, was launched from scratch by combining the track record of legendary producers and directors (Steven Spielberg, Jeffrey Katzenberg, David Geffen) and backing by an enormous investor with Paul Allen (Microsoft cofounder), reportedly investing $500 million. Its initial credit facility was replaced by a $1.5 billion financing deal in 2002:

DreamWorks Announces New Financing

Los Angeles—DreamWorks LLC today announced that it has closed two major financing transactions totaling $1.5 billion. The new financing consists of a $1 billion film securitization—the first of its kind in the film industry—as well as a $500 million revolving credit facility. Together, these financings replace the Company’s existing financing arrangements at a substantially lower cost of capital and extends the Company’s access to debt capital until at least October 2007.

… The securitization uses a unique structure that finances expected film revenue cash receipts from DreamWorks’ library of existing films, as well as from future live action releases. According to the terms of the securitization, funds are advanced after a film has been released in the domestic theatrical market for several weeks, at which point the film’s revenue stream over a multi-year period is highly predictable. In part, this predictability allowed the transaction to gain investment grade status from the two leading rating agencies …29

It is accordingly not surprising that if an entity with an unproven track record but lots of cash can join the co-financing game, that a large independent with a sustained track record ought to be able to arrange significant financing for its own slate. This trend was started, in part, by Revolution, but has now expanded to a myriad of independents, such as Village Roadshow and Summit Entertainment. The amounts these companies are now able to raise are on par with studios, and gives the original DreamWorks financing a mundane air. Summit, of Twilight fame, had negotiated a $750 million refinancing in 2011;30 then, post Lionsgate’s acquisition of Summit, Lionsgate sought a new credit line of equal amount in 2012.31 Village Roadshow, the independent with perhaps the longest track record—having distributed pictures via Warners since the late 1990s (and with a library at the time of its new financing of over 65 films)—secured $1 billion in financing in 2010, enabling it to produce films such as Sex and the City 2.32

When companies such as DreamWorks, Lionsgate, and Village Roadshow can raise in the hundreds of millions of dollars, and even secure revolving lines up to $1 billion, to finance their slates, it would seem there is a fine line between production company and studio; however, remember, as discussed in Chapter 1, that a key defining element of a studio is global distribution infrastructure—developing, producing, and financing product goes a long way, but product still needs to be marketed and distributed globally, and through all channels. As difficult as it may seem to grasp, $1 billion in financing does not in itself create a studio. Expanding to this next level (as well as diversifying production to cover other major markets, including TV) is extraordinarily difficult, as was borne out by the original DreamWorks SKG ambition.

Angel Investors

Similar to a venture capital structure, the film business tends to attract wealthy individuals that want to invest in pictures. These types of deals vary widely, but there seem to be a couple of consistent themes. First, the investor, while wanting a return, has a secondary objective of passion/fun/ego, and will accordingly take a producer or executive producer credit; of course, this is not unfair, in that much of the role of an executive producer can be putting together financing. Second, the investor is usually contributing a sizable amount of the budget. These individuals are high-stakes players, investing likely for high risk, high reward, rather than just as a gap financier. In fact, there is often a personal passion for the project, and the angel investor may be putting in money because, simply, he or she wants to make the film.

A high-profile example of an angel-financed film is Polar Express. Steve Bing, heir to a real estate fortune who turned to entertainment, partnered with Warner Bros. to back the Robert Zemeckis-directed (Back to the Future, Forrest Gump, Who Framed Roger Rabbit?) animated holiday film Polar Express, starring Tom Hanks. The film was considered risky given its $165 million budget (with some reports speculating it was more than $200 million) and pioneering motion-capture animation technique (to give a unique look and range to animating human characters). Warner Bros. hedged its risk by partnering with Bing, as Business Week reported: “And even folks at Warner Bros. are said to be thrilled that multimillionaire Steve Bing, who aspires to be a big-time producer, has put $80 million into the film. He’s also covering half the $50 million or more in marketing expenses, according to a source with knowledge of the deal. Says the source: ‘If it tanks, it won’t leave Warner with that much of a hole [thanks to Bing].’”33

Sometimes the lines between an angel and a fund can blur, as seems to be the case with Alcon Entertainment. FedEx founder and CEO Frederick Smith teamed with Alcon founders to launch My Dog Skip (initially headed to DVD), and then went on to become an equity partner in a multi-picture financing deal, reportedly worth $550 million, with Warner Bros.34 Another example where the line is blurry between a production company and an individual is billionaire Philip Anschutz, who backed Walden Media as an independent studio, financing generally family fare such as The Chronicles of Narnia (originally with Disney). As was depicted in Table 3.3, there are many new entrants in this arena, including Oracle founder Larry Ellison’s kin Megan and David Ellison, who respectively launched Annapurna Pictures and Skydance. There are countless similar stories given the allure of Hollywood—most of them are simply less high-profile and outside the public eye.

Crowdsourcing is a relatively new phenomenon, enabling individuals to contribute to projects via the Internet. What companies offer are perks, sometimes phrased as “VIP elements,” rather than actual stock or profit participations in projects. Two of the largest sites that focus on media productions are Kickstarter and Indiegogo. Kickstarter, which bills itself as “the world’s largest funding platform for creative projects,” allows anyone to post a project, and then with a ticking clock waits to see if all of the financing is contributed. If the financing goal is not reached, then no money is accepted and the project does not move forward—in its website section on “How Kickstarter Works,” the site explains that the all-or-nothing method is designed to protect everyone involved, and bluntly proclaims: “This way, no one is expected to develop a project with an insufficient budget, which sucks.”35 In contrast, Indiegogo offers content creators to select either a fixed-funding or flexible-funding scheme, where, again, in the fixed scenario if the goal is not reached, then no fee is taken, and no money accepted (all contributors are refunded). Pursuant to the respective websites, the companies/sites charge a percentage fee from the funding total (e.g., 4 percent or 5 percent, which is only collected on a fixed-funding goal if the threshold is met) and a market rate credit/payment processing fee; Indiegogo charges a higher rate (9 percent) on funds raised for “flexible funding,” where the creator keeps whatever is raised without a threshold needing to be met.

Neither financing site takes equity ownership in projects, and are designed to allow creators to democratically raise money by outlining a project and setting a goal. In return for contributions, funders receive different levels of rewards tied to donation level. For a game, for example, a contributor might receive a downloadable copy once published, or for a larger contribution perhaps a signed copy of an element from the developer, or some form of direct engagement with the developer/producer (e.g., a lunch or conversation).

Historically, these sites tended to fund niche projects, with tens of thousands of dollars raised; however, in 2012, Double Fine, a San Francisco games company, broke through the clutter and defined the potential of crowdsourced project financing. Posting a description of a game it wanted to make and seeking $400,000, in February 2012 Double Fine raised $800,000 within the first eight hours, over $1 million by the next day, and within a week of posting nearly $2 million. Double Fine could accordingly boast that it was the first independent studio to fully fund a game via Kickstarter. Although Double Fine is the exception, it does prove the case of an independent with a track record and following able to crowdsource its fans and finance future productions.

Similarly, Kickstarter is being leveraged by Hollywood independents, such as Bret Easton Ellis (author of Less Than Zero, and producer of The Informers) and Paul Schrader (screenwriter of Raging Bull and Taxi Driver, and director of American Gigolo) for their movie The Canyons. They are utilizing Kickstarter, essentially, for gap financing, seeking $100,000 to complement their own investments in the project.36 In return for contributions, the following are some examples of what a donor can receive: at the lowest tier, for $1, a contributor will receive a highresolution poster download; for $100, they are offering tickets to a private cast-and-crew screening, together with a copy of the DVD (or Blu-ray); and, for $5,000, Bret Easton Ellis will read and review your novel, post the review on an international blog or website, and you will be granted an associate producer credit on the film. In a short timeframe, Ellis and Schrader reached their target and more (generating $159,000 against a posted target of $100,000).

Although neither Kickstarter nor Indiegogo allow direct equity investment in a project, in order to avoid securities laws violations, many crowdsourcing proponents have advocated a loosening of the regulations to enable smaller companies to raise capital via more micro-finance means. In March 2012, as part of the JOBS Act passed by the U.S. Congress, a section entitled “Entrepreneur Access to Capital” attempted to pave just this path. The law includes a specific crowdsourcing exemption, allowing private companies to raise up to $1 million per year, and sanctioning capital-raising via the Internet through websites registered with the SEC. (Note: There are various conditions attached, rules are being adopted, and many are concerned about the abrogation of historical protections and the potential for fraud, which has caused the crowd-sourcing community to preemptively set standards via the Crowdfunding Accreditation for Platform Standards self-policing policy.37)

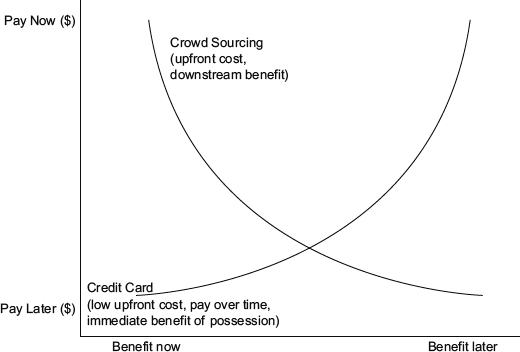

What is interesting about the new regulations, coupled with the growth of crowdsourcing generally, is how to define the actual investments. If, for example, an individual gains a specific benefit from the transaction, such as a copy of the to-be-produced product, then the fundraising is akin to a pre-sale; similarly, if there is a bundled benefit for a higher-tier donation (e.g., contribute $20 and Company X will provide you a downloadable copy of Y when it is complete, and for $100 you get the copy plus a value-added item, such as a signed animation still from the director), then the pledged financing can be construed as an advance purchase. Crowdsourcing is really the inverse of using credit cards (Figure 3.2). The credit card industry created consumer liquidity by enabling purchasers to buy a product (and take ownership/access) now while paying later; whereas, with crowdsourced financing, company liquidity is created by taking payment now while pledging to deliver the product (transfer ownership/provide access) later. (Note: In accounting terms, this is the difference between an account receivable and a deferred liability.)

Figure 3.2 Crowd Sourcing Funding—For Consumers, the Inverse of Credit Card Financing

International coproductions are the norm with films originating in Europe, as domestic markets often cannot support the full costs of a high-budget film, especially when the cast/production is associated with a particular language. The film Cloud Atlas, an ambitious project of Andy and Lana Wachowski, the sibling team behind The Matrix series of movies, pushed the limits of independent international productions. With a reputed budget of $100 million and a blockbuster cast including Tom Hanks, Halle Berry, and Hugh Grant, among others, the film was a German–American–Asian coproduction not only with multiple locations, but also multiple principal crews and directors. Asian investors contributed more than one-third of the budget (approximately $35 million), which included substantial investments from South Korea (Bloomage Company, a Korean film distributor), Singapore (shipping magnate Tony Teo), Hong Kong (major film distributor Media Asia Group), and China (Beijing film company Dreams of the Dragon). Significant financing was also contributed from Germany, where subsidies (e.g., German Federal Film Fund) reportedly accounted for approximately $18 million; given that one of the film’s directors, Tom Tykwer, is German, the head of the German Federal Film Fund was quoted as saying, “From our perspective, Cloud Atlas is a German film.” Add to this that Warner Bros. is the U.S. distributor (at least as of the date of production was not a major financial contributor), the movie is a classic independent film, with sources cobbled together from global sources, set in multiple overseas locations, with investors from Asia, Europe, and the U.S. alike claiming pride of ownership.

What makes the financing truly unique, however, is that to weave this creative and financing quilt for a film that involves multiple interrelated stories (in different times and places), there were two different film units and crews shooting simultaneously. This production scheme maximizes the efficiency of shooting, with actors moving between different roles, even on consecutive days. In discussing the financing, the New York Times noted: “The idea of shooting on parallel tracks, with the Wachowskis directing one unit and Mr. Tykwer the other, grew from a realization that the stars were more likely to work for a steep discount if the shoot could be finished in half the time. Actors also play different roles in different time periods, keeping them busy and, on certain days, turning stars into extras.”38

Rent-a-Distributor: When a Producer Rises to Studio-Like Clout