The ability to watch a movie or TV show at home on a videocassette, or DVD or Blu-ray disc, has had a profound impact on the economics of the motion picture and television business. Not only has the video market altered the consumer’s consumption pattern of watching movies, but it has also changed the underlying financial modeling of whether a movie, and in cases TV shows, are made in the first place. Despite the rapid and wide market penetration of new technologies such as DVDs, it is a testament to the cultural impact of videocassettes that the studios, at least colloquially, still refer to their divisions as Home Video. In fact, the word “video” in this context has become a misnomer, a catch-all of sorts that conceptually captures the varied devices that have evolved allowing consumers to watch films on their television, over a computer, via game systems, or more recently via tablets and other portable means.

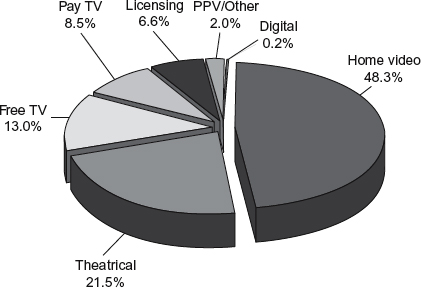

In terms of profitability, the video market has provided a boon to studios’ bottom lines. While the profitability on a new movie is generally measured in a single life cycle (e.g., theatrical, video, television, ancillary and new media revenue streams), the video market has added the magic of reincarnation by inducing consumers to keep buying the same product again and again with each new technological upgrade. The net result is that home-video revenues (i.e., revenues from sales of physical discs) grew to represent about half of studios’ total film revenue. Figure 5.1 below illustrates how, in the early to mid 2000s, video captured nearly half of a studio’s revenue pie1; Figure 1.5 (see Chapter 1), in contrast, depicts how that percentage has dropped precipitously to roughly one third in the last five years or so.

Figure 5.1 Studio Revenue Breakdown, 2007

© 2009 SNL Kagan, a division of SNL Financial LC. All rights reserved.

Although this percentage has been steadily declining from its peak of roughly 50 percent of total revenues, the absolute numbers remain significant, and entering 2012 video still remained the single largest revenue segment (again, see Figure 1.5). Additionally, and quite importantly, beyond capturing the biggest slice of the revenue pie and exploiting the churn factor, the studios have managed to keep a larger share of the video revenues. Typically, studios (and networks, as applicable) pay participations based on a royalty percentage rather than accounting for the gross sums, which in turn makes video distribution uniquely profitable.

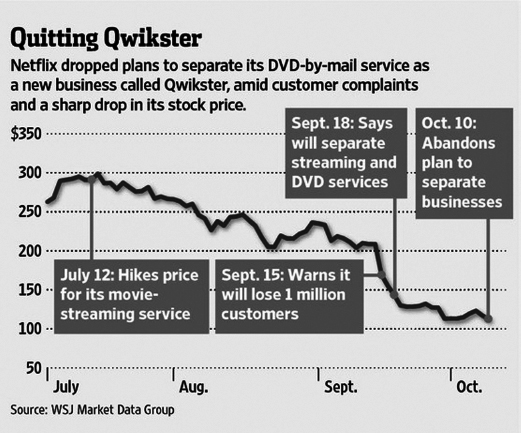

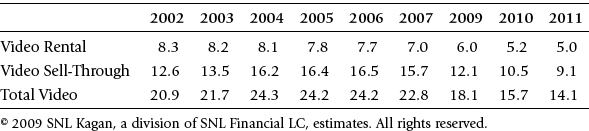

The evolution of the home video business is not over, and in this chapter I will review the genesis and growth of this approximately $14 billion market segment (down from a peak of $24 billion; see Table 5.1 on page 207), explore the radical changes that have taken place at retail distribution since the early 1990s, and discuss the underlying P&L models of how the business works and why videocassette/DVD/Blu-ray distribution returns some of the highest margins in the distribution life-cycle chain. I will also review how this ancillary revenue source has spawned profitable original production (i.e., made-for-video), discuss marketing nuances driving home video consumption, outline some of the profound technical changes that have been catalysts for a reinvention of the category, and explore the impact that video release patterns/windows and piracy have had on the other parts of the business.

Finally, although new technology applications, including downloads and video-on-demand (VOD) access are inextricably tied to the future of the video market, I address these growing markets (together with watching video via tablets and other portable means) in Chapters 7 and 8, and focus here on the traditional video market. Nevertheless, I will touch on aspects such as the intersection of electronic sell-through (i.e., downloads to own) and the implications of infinite shelf space and depth of copy compared to physical retail sales.

In summary, this chapter will explain how and why the video business (again, here meaning physical discs as opposed to on-demand/digital permutations) has emerged to drive the largest positive cash flow of any studio division, while at the same time providing the safety net for studios to make certain pictures at all. With this level of vested interest in the business, it is not surprising that studios and networks alike are schizophrenic regarding download and other new technology platforms that are expanding video’s reach while threatening to replace what has evolved into a pillar of the studio distribution (and financing) infrastructure.

To grasp the value-for-money proposition inherent in marketing a DVD of a hit movie, simply pause to think about one of your favorite recent films. That movie probably took over five years (and likely many more) to move from concept to release in theaters; over that period, hundreds, if not thousands, of people were involved in the production and release of the movie. On the financial side alone, and assuming the film is a major studio picture, it probably had an investment risk, including costs of producing, marketing, and releasing the film, of over $100 million. Wrap those years of hard work, incalculable passion and creativity, and dollars together and what do you have? You, the consumer, can take home a product that cost the studio over $100 million and years of work for about $20, and often less; better yet, you can rent the movie for about $3.

Whether renting or buying, the product is also perfectly tailored to the freedoms made possible via innovations in the consumer electronics industry: you can watch it when you want and where you want. This pitch is not often made overtly, but at a subliminal level, when advertisements say “own it today” or “bring it home today,” they are saying you can own for $20 what it took us over $100 million to make, and you can watch it over and over for free and at your leisure. You do not have to go back very far when the concept of an average citizen owning a movie and watching it at home was beyond the grasp of reasonable expectations.

What other products can compete with the value of a video? Perhaps a record or CD of a concert, capturing the moment, are somewhat equivalent. If you had asked the people starting up studio video divisions, many of whom migrated from the record side, whether they would be happy to be as large as the record companies, they would have thought you were crazy. Certainly, it was not within upstart business plans that the revenues could come to surpass the music industry. It is not a stretch to state that video recorders and videos, and the improved technical iterations spawned, including most prominently DVD and now Blu-ray, have been considered the most important product invention to hit Hollywood since television. And yet, as grandiose and accurate as this statement may be, the pace of change in the online world has been so great that it is conceivable to view VOD access as quickly usurping the video mantle; VOD access, though, benefits enormously from the consumer renting culture spawned by home video, and to understand the shifts today and the economics of VOD access (whether à la carte or subscription, streaming or download) it is important to appreciate the models, history, and economics of video that paved the way for personal/home viewing.

Accordingly, I will touch on a number of questions: How did video turn into big business? Where is the business headed, and why has it become the lifeblood of studio profitability? Is it possible that just as quickly as the video market grew to dominate distribution revenues, we are at the cusp of a decline so steep that in a few years, videos/DVDs/Blu-rays may disappear? Will the traditional video market be relegated to a historical footnote along with physical film prints, and be entirely replaced by on-demand digital media accessible via a range of new devices, including living room staples (TVs and game systems) and a host of portable devices (e.g., tablets)?

History and Growth of the Video Business

Early Roots: Format Wars and Seminal Legal Wrangling

The first consumer-targeted videocassette recorders were marketed in the 1970s, when Sony introduced the Betamax VCR. The introduction of the VCR faced the same chicken-and-egg dilemma that now seems commonplace with every new technology targeted at consumers’ consumption of entertainment: Was there a match between the hardware and software base? When Sony’s system was introduced, there was essentially neither software nor hardware available, much like the problem facing the launch of the DVD industry 20 years later in the mid 1990s.

To overcome such a hurdle, at least one party needs to take an enormous risk. In the case of the DVD, it was Warner Bros. leading the charge (see page 212, “Early Stages of the DVD: Piracy Concerns, Parallel Imports, and the Warners Factor”), but the true early pioneer of the business was Sony in the days of the Betamax introduction. Interestingly, and disproving the first-mover advantage, despite building the market (and to many having a superior format/product), Sony did not emerge as the leader.

Sony’s visionary idea was that consumers would pay to be freed from television’s broadcast schedule (sound familiar today?): the Betamax VCR would allow them to watch programs when they wanted, not as dictated by the network’s broadcast schedule. The VCR was not originally positioned as a playback device for movies. Sony’s CEO, Akio Morita, said at the time: “People do not have to read a book when it’s delivered … Why should they have to see a TV program when it’s delivered?”2 Accordingly, Sony marketed the Betamax VCR hardware player, which utilized a proprietary tape generically called the Beta format. Its marketing campaign echoed Morita’s theme, pitching the player as a machine allowing consumers to “time-shift”: consumers could record television programs and view them later at a more convenient time.

Whether history is repeating itself or technology advances enabling services such as Hulu are finally realizing Morita’s original vision, it is clear we are now on the threshold of totally taking the programming out of the broadcast scheduler’s hands. As alluded to in Chapter 6 and further discussed in Chapter 7, not only have DVRs made recording easier, but we can now envision (and, in fact, already experience) future iterations where TV is consumed in a playlist fashion, where viewers through VOD or other access select the programs they want to watch and then consume them according to their own programming schedule (which may be optimized or random).

Returning to the roots of the business, two factors greatly contributed to the explosive growth of the VCR market. First, and a point not often cited (and I will admit somewhat subject to challenge), the advent of the VCR was in the same general period as the emergence of cable TV in the U.S. Not only was the notion of time shifting attractive, but it was even more attractive in an environment of blossoming program choices. For decades, U.S. consumers were limited in programming choices to the three major broadcast networks plus a handful of local UHF stations; with cable TV came an explosion of choice.

Second, and more importantly, the ability to rent movies from video stores caught on like wildfire—the concept of building a library of tapes and renting tapes out for a price no more than a movie ticket proved revolutionary. Independent stores, which quickly gained the industry nickname “mom and pops,” led the growth and proliferated throughout neighborhoods. It was an ideal small business, preying on pent-up demand and taking advantage of modest start-up costs (including the need for limited space); further, video rental was a cash business that built a loyal customer base virtually on its own via a regular supply of new product.

As great as this seemed for Sony and the new breed of video rental entrepreneurs, the whole notion of video rental seemed a looming disaster for the Hollywood studios who produced the films. The studios saw the VCR as a means of copyright infringement. The underlying economic fear was that individuals would copy movies and TV shows (and keep them for a home library), which would undermine the market to exhibit the programs on television. Universal’s president, Sidney Sheinberg, upon seeing the Betamax time-shifting campaign, and fearing the loss of revenues that could lead from unauthorized copying of Universal’s product, sued Sony for copyright infringement.

The resulting case, which was initially brought in 1976 and ultimately decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1984, was a landmark lawsuit that paved the way for DVDs, arguably saved the studio system, and is once again being pointed to as threatening the integrity of the distribution system (as new online services push the VOD envelope).

The Betamax Decision: Universal v. Sony

The ultimate finding in what has come to be known as the “Sony Betamax” case is that time-shifting via home copying for noncommercial purposes was permitted (in legal jargon, a fair use and non-infringing of copyright; for a further discussion of copyright, see Chapter 2). Before the Supreme Court reached this verdict, Sony Corp. v. Universal City Studios3 went through a litany of phases, with each side supported by name-brand media allies. Universal was joined by Disney, who saw similar infringement of its copyrights and potential loss of television broadcast revenues. Sony was supported by the sports leagues, including commissioners of the national football, basketball, baseball, and hockey leagues; these leagues believed that VCRs were a benefit to live events, allowing fans/consumers to see games they would have otherwise missed. Another important Sony supporter was the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, believing that it was a good thing for children to be able to see educational programming and that VCRs promoted this end; further, it was endorsed by Fred Rogers, the star/producer of the classic preschool show Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.

In the end, after an eight-year legal odyssey, the Supreme Court reasoned that a significant number of copyright owners would not object to their content being time-shifted, that there was insufficient proof the ability to time-shift would undermine the value copyright holders would receive from licensing their content to TV (which proved to be true, as license fees increased over the following years), and therefore the Betamax was capable of “substantial non-infringing uses.” Interestingly, the Supreme Court, in an almost prescient statement recognizing that new technological advances—advances like the Internet, file sharing, and VOD access via social media, of which it could not have been aware—would force it to consider the broader issues in the future:

… One may search the Copyright Act in vain for any sign that the elected representatives of the millions of people who watch television every day have made it unlawful to copy a program for later viewing at home, or have enacted a flat prohibition against the sale of machines that make such copying possible.

It may well be that Congress will take a fresh look at this new technology, just as it so often has examined other innovations in the past. But it is not our job to apply laws that have not yet been written. Applying the copyright statute, as it now reads, to the facts as they have been developed in this case, the judgment of the Court of Appeals must be reversed.

It was a close decision (5–4), and whether or not one agrees with the logic (or cynically believes that the court needed to craft a political opinion, allowing the flourishing video business to continue), the video business was officially sanctioned. By 1986, just a couple of years after the landmark Sony decision, combined video rental and sales revenues ($4.38 billion) exceeded the theatrical box office ($3.78 billion) for the first time. By 1988, rental revenues alone ($5.15 billion) exceeded the theatrical box office ($4.46 billion).4

Among the ironies of the case is how the party most vested in the case (Sony) ended up losing the battle for consumer dollars, and how the plaintiff (Universal) came to be bought by one of the hardware manufacturers that benefited from the verdict. Matsushita, the parent of the Panasonic brand, and sister company to JVC (together with nonaffiliated Hitachi), developed and marketed the rival VHS format, which was incompatible with the Sony Betamax player. It was the VHS format that took hold and, by the mid 1980s, dominated. Video retailers did not want to stock alternate formats, and as VHS players became more dominant, more VHS titles were stocked and the spiral grew until Sony’s Beta format was doomed. Within a few years of the Sony v. Universal decision, Sony threw in the towel and started manufacturing VHS players. Perhaps adding injury to insult, only a few years later the format war winner Matsushita bought MCA/Universal in an acquisition touting the merger of hardware and software.

The Sony Betamax case continues to mark an important turning point for the distribution of content onto in-home hardware, as well as serving as a precedent for the current age of digital age cases such as Napster, Grokster, and Cablevision (see Chapter 2).

The Early Retail Environment: The Rental Video Store

When videocassettes were new, and market penetration of VHS recorders was growing in the 1980s, the video business was almost entirely a rental business. By rental, I mean conventional rental stores such as Blockbuster Video or Hollywood Video (household brands that many under 25 may now not know).

At first, when the rental market was exploding, it was dominated by neighborhood video stores. The economics were relatively simple. The video store would buy units of movies from the studio distributor, and then rent the cassettes out to customers. The store would perform a simple break-even analysis of how many times a particular unit would need to be rented to turn a profit. There were some add-ons to mimic movie environment, such as selling popcorn or candy to take home with your movie. Marketing was relatively unsophisticated, led by film posters supplied by the studio distributors to advertise the hit and coming films.

As the business grew, chains formed and eventually dominated. At first, it was actually an acceptable retail strategy to be out of stock. If a store did not have enough units of a title, people would rent something else and come back for the other film; disappointment was a fundamental and accepted marketing strategy. This allowed the store to profit on two fronts: retailers could keep inventory down, not making risky decisions of possibly overbuying on a title, while virtually assured of repeat-customer business.

For a period, consumers seemed to accept the delay as part of life, and would happily rent a movie other than the one they had come in for. The out of luck, but somehow not entirely dissatisfied, customers would come back for the film they really wanted when: (1) the store called to let them know the title was back in stock (if they had placed their name on the reserve list); (2) at a somewhat random later date in the hope that they would be lucky and a copy would be available; or (3) at an even later date when they felt demand must have waned and they would have a really good chance that the title would be available to rent.

Amazingly, this lottery style mentality to renting did not dissuade consumers, and to some degree it helped fuel the growth and diversity of content offered by video retailers. Video stores recognized this phenomenon and were pleased for customers to rent a second- or third-choice title; as previously noted, this virtually guaranteed repeat business when the consumers returned the title they rented, but had not really wanted, and came back to rent the film they had come for in the first place. As a business model, this was almost too good to be true. Whenever one can make this type of statement, though, change is afoot. With the maturity of the business, impatience grew and consumers no longer accepted dissatisfaction as the rule.

Over time, rental stores became more competitive and needed to develop more traditional marketing campaigns to ensure customer loyalty. All types of schemes were implemented, from “rent 10 videos, get one rental free” loyalty programs, to store clubs that came with discounts, privileges, and mailings. More sophisticated chains divided customers into complex marketing matrixes, looking at who were frequent renters, casual renters, deadbeat clients, etc., and devising targeted campaigns to increase rental frequency and store loyalty. As the chains grew, they also started to advertise directly, advising customers “Come to Blockbuster and rent growing their business with an injection of direct marketing dollars plus cooperative marketing spends set out in their agreements with the product suppliers. As in any other product category, choice, growth, and competition added complexity, and rentals started to have price differentiation. Examples of offers included: “buy two, get one for free” deals, keep the title for the same price for the weekend, and rent new titles at full price for one night while offering older titles for the same or lesser costs to keep for three or five days.

Finally, as a tangible example of the market maturing and retailers acknowledging that disappointing customers was not the best long-term strategy, marketing schemes shifted 180 degrees to implement guarantees that new titles would be in stock (and, if not, the rental would be free). When a new title came out, there would often be pent-up demand similar to that which creates lines at movie theaters. To the “I’ll wait to see it on video” crowd that had socially developed in response to the growth of the industry, the video release date was like a premiere. New titles, which a few years earlier would be gulped up the moment they hit shelves and be out of stock, would now be available in large quantities.

This marketing shift also had a direct economic consequence on competition. To satisfy demand, a store needed to have key new titles in sufficient quantity, which required a larger upfront investment. Whereas 10 or 15 copies may have been fine before, 10 times that number would now be required. An average retail price, which, at the time when rental was king in the 1980s and early 1990s, was approximately $70–$100, could change the inventory investment for one title from $700–$1,000 to over $10,000. Volume discounts may have allowed some lower average pricing, but the elasticity was not great and the net effect was pressure squeezing the smaller, “mom and pop” accounts. Not surprisingly, this timing coincided with increased clout from major chains, such as Blockbuster and Hollywood Video, which had begun expanding and gobbling up smaller outlets to become independent market forces. Between 1987 and 1989, Blockbuster grew from a 19-store chain to over 1,000 outlets, and in 1988, with just over 500 stores, became the country’s top video retailer, with revenues of $200 million; growth did not slow down, and through further expansion and acquisitions the chain grew another 50 percent to 1,500 by 1991 before finally being acquired in a merger with Viacom in 1994.5 The market was vibrant enough that, with enough stores, chains could go public, and rival video chains Hollywood Video and Movie Gallery both completed public offerings in the early 1990s.

And change was just beginning. The dominance of the rental store was about to give way to the sell-through market, with rental revenue sharing becoming an intermediate solution to lower-priced units in a still-vibrant rental market.

During the growth of the rental video market, a new pattern was slowly emerging that would ultimately overwhelm rental sales and even threaten to eliminate the rental store completely: direct sales of videos to consumers. In trade lingo, this became “rental versus sell-through.” Today, the rental store seems to be facing extinction, combating the dual forces of downloads for purchase—“electronic sell-through”—and VOD access for rentals (both forces are discussed in more detail in Chapters 7 and 8, and serve as fodder for analysts who forecast new technology applications leading to the demise of historical markets).

The challenge in this earlier battle for survival was not played out as a public drama, as sell through was not initially perceived as a threat to rental’s dominance. In fact, conventional wisdom questioned whether consumers would want to purchase a videocassette when it had become so easy and relatively inexpensive to rent a film. One threshold issue was: Would people really want to watch a particular movie more than once? The general consensus was no. Those customers who were passionate about a particular movie might rent it a few times, but for the rental store, which had invested substantial sums per copy of a title, there was every incentive to entice these fans back to re-rent the title.

For the video store, the game was still all about amortization of inventory cost based on turn: How many times did an individual cassette/copy need to be rented to break even? Obviously, it was an attractive business model to turn a copy many times rather than sell it once. Simply, if a copy of a blockbuster cost the rental store $50, and the outlet charged $5 per rental, the store needed to rent that copy 10 times to recoup. Moreover, because each film is unique, inventory obsolescence only applied to the physical materials (e.g., how long a cassette could be rented before the tape quality degraded to an unacceptable level). A title that had paid for itself could sit on the shelf as catalog inventory, providing pure profit for the indefinite future (subject to the number of copies originally stocked, as a store would obviously keep fewer copies in catalog than were acquired during the peak rental period of initial video release). In fact, one might say this was the first iteration of the “long tail” now so commonly discussed online. Accordingly, a hit title that needed 7–10 rental turns to recoup might have multiple future rental turns left, yielding more than a 100 percent return on investment on a per-copy basis.

If a title was able to generate over 100 percent ROI, then the business model to sell that unit was initially far from compelling. Ultimately, the model comes down to the simple elements of units and pricing. At the early stages, the cost per cassette made it difficult to create a margin allowing for markups to challenge the relative earning power of a rental unit. Even at a substantial markdown, such as to $20 inventory cost, the retail pricing was quite high; moreover, there was a disincentive to lower pricing significantly when the rental business was thriving. A bigger obstacle, however, was simply the pattern of consumer consumption. The whole video market had exploded seemingly overnight, and people were used to renting, not buying. Something would have to fundamentally change to shift that pattern, including a dramatic lowering of inventory cost.

Table 5.1 U.S. Retail Home Video Industry ($ billions)

Not surprisingly, though, as in most consumer goods markets, prices inevitably started to come down. This was forced by pressure from large chains that demanded lower pricing for buying greater depth of inventory. More important than pressure from the rental stores, however, was the fairly rapid market shift from a predominantly rental business to a retail-dominated industry. Just like renting had before, buying videos became a quickly adopted consumer behavior.

By the time the DVD market reached its peak in 2004–2006 (see the next section), and as evidenced by Table 5.1, the percentage of sales for sell-through had shifted to close to 70 percent, whereas only a few years before the split was nearly even.

Key Factors Driving Growth in the Sell-Through Market

Among the key changes driving the growth of the sell-through market were: (1) the growing trend for consumers to collect videos; (2) the decline in pricing, allowing consumers to purchase titles for the same amount of money as (or at least not much more than) a record/CD; (3) studio efforts to sell mass volumes of select hit titles; and (4) the growth of the kids video business, initially led by Disney.

Examining these factors in a bit more detail, as the pattern of watching and renting videos matured, people started the habit of collecting titles. Although now accepted as commonplace, this was hardly an inevitable turn. Market research will tell that most purchased videos sit on the shelf: How often do you re-watch a movie that you have bought? For some favorites and classics, of course, the answer may be yes, but once collecting transitions from buying your favorite film to a habit, the answer will likely be different. And that is the key—becoming a habit—seducing you to purchase titles that do not quite make your top all-time list. As collecting became in vogue, studios started to mine their libraries and make older titles available, expanding the range of consumer choice. First there were books, then records, and now videos; in fact, the lingo that evolved was “video libraries.” People started to buy videos, sometimes never even watch them, and keep them on the shelf as a new sort of trophy or archive.

And once a piece of media becomes a collectible, it becomes a gift, opening an entirely new marketing direction for sales. Studios, if nothing else, are brilliant marketing machines, and all video rights holders drove a truck through the opportunity to encourage sales as gifts. The fourth quarter is now the largest period for video sales (with the holidays an ideal time to launch gift sets and special editions), which is a far departure from the origins of the video rental business.

Second, and somewhat hand in hand, the market saw a reduction in pricing and a corresponding upturn in sales of mass volumes of a title. By the early 1990s, as the rental market was maturing and chains grew and consolidated, there was a rule of thumb that you could place 200,000 to 300,000 units of a key new title in North America. For a title that was not a hit or one without a star driving sales, this number could be halved, while a big hit might sell twice this number of units. The key point is that there was limited elasticity of volume in rental.

Studios salivated at the notion of selling millions of units of a title, and on big hits it became commonplace to run break-even comparisons to assess how many units would need to be sold at retail to justify a “sell-through” release (sales direct to consumer as opposed to rental). While sell-through means direct sales to consumers, what it implicates at the distribution level is a whole new set of pricing and a dramatic expansion of retail outlets. The retail infrastructure for direct-to-consumer sales had to be built, and the expansion of outlets to mass merchants, drug stores, supermarkets, record stores, and independents took years to mature. In point-of-sale terms, this could mean going from low thousands of outlets at video rental to over 30,000 outlets for direct-to-consumer sales.

The challenges that came with the sell-through market were the same as any other consumer product: inventory management, advertising, in-store merchandising, physical distribution, and order of magnitude issues in physical manufacture. This was a daunting and, at some level, risky challenge for an industry that was thriving on limited distribution to a finite group of key customers, and where inventory management (video rental was largely a no-returns business) was a relatively minor issue.

So, putting aside the growing pains of becoming another consumer product challenging soap for advertising time and store shelf space, the nuts-and-bolts question became: What was the multiple needed to sell at sell-through versus a rental release? An important, and to the studios somewhat comforting, element in the matrix was that rental was still important. On any title significant enough to justify a sell-through release, there was a built-in sale to all video stores. The studio could still sell its few hundred thousand units into the channel; it would simply earn a significantly lower margin, charging a wholesale price of $15–20+ as opposed to the highly profitable $50–70+ rental price. For a period, and for many years following in several international markets, there was even the ability to price differentiate. The supplier (i.e., studio) would charge a higher price for rental units sold to video stores, and create a separate, lower suggested retail price (SRP) for mass-market sell-through buyers.

The analysis was then a straightforward break-even equation, taking into account the sales uplift needed from a lower-priced good to surpass the revenue and contribution margin of the higher-priced, lower-volume rental units (with variable manufacturing and marketing costs factored in on the expense side). As a rule of thumb, it turned out that a title needed to sell a roughly 4:1 or 5:1 ratio to justify a sell-through release.

The ultimate accelerant for the sell-through market was kids videos, in particular the emergence of Disney as a dominating force via its video division, Buena Vista Home Entertainment. Earlier, I pointed out the issue of whether people would watch a video repeatedly; the one area where this was clearly true was with children. Simply, kids would watch the same video over and over and over. It does not take a brain surgeon to recognize as a parent that buying a cassette for $20 that your kids will watch seemingly 100 times is a good investment. To the parent that can gain an hour or more of near-guaranteed peace and quiet, the value of the purchase is worth infinitely more than the cost. Hardly a babysitter could trump the satisfaction of a Disney video, and the combination of a babysitter and a Disney classic was as good a bet as there was out there.

Disney quickly recognized the gold mine that lay before it, and the timing not so coincidentally dovetailed with the reinvigoration of its animated film business. With hit after hit, commencing with Beauty and the Beast in 1991 and Aladdin in 1992 (see Table 5.2), Disney was validating a new market and spinning box office gold both in theaters and then again on video—a classic example of repeat consumption as a key factor in maximizing value per Ulin’s Rule. Then, in 1995, The Lion King broke out of the box, reportedly selling a staggering 30 million units,6 with reputedly 20 million units in its initial release window. The notion of 20 million units of a title had been seemingly unimaginable previously, and once the pattern of high volumes proved repeatable, there was no stopping. It continued for more than a decade, with Finding Nemo selling 20 million combined DVD and VHS units in its first two weeks of sales in November 2003, including 8 million on its first day of release for a record beating the prior Spider-Man tally.7 Everyone tried to jump on the bandwagon, but during the 1990s growth spurt, Disney seemed to have a lock on printing money between box office success of animated titles and the amazing upside that the video industry provided.

Table 5.2 Disney Animated Releases by Year

Year (Theater) |

Title |

1989 |

The Little Mermaid |

1991 |

Beauty and the Beast |

1992 |

Aladdin |

1994 |

The Lion King |

1995 |

Toy Story |

1996 |

The Hunchback of Notre Dame |

1997 |

Hercules |

1999 |

Tarzan, Toy Story 2 |

Year after year, they continued to release a new hit, which became an instant classic given the numbers (though nothing again reached The Lion King heights) and had strong enough brand awareness to spur made-forvideo sequels (see later discussion, “Beyond an Ancillary Market: Emergence of Made-for-Video Market).

The success of Disney videos catapulted the head of Disney’s video division, Bill Mechanic, into executive stardom, and in the mid 1990s, he left Disney to become president of 20th Century Fox studios. In terms of animation, Mechanic never hit the peaks at Fox he experienced at Disney; acquiring Don Bluth studios and launching titles such as Anastasia helped Fox enter the lucrative market, but they failed to create a Disney-like brand engine from the genre. (Note: Fox eventually succeeded years later in building an animation brand via Blue Sky and its computer graphics hit franchise Ice Age.)

The Emergence of and Transition to DVDs

The video market has been nothing short of a cash flow godsend to studios and producers. After the initial growth of rental and the consumer acceptance of the direct-to-retail sales model, the market took off again. The next phase was the development of the digital video disc (“DVD,” or in technical circles actually the digital versatile disc).

Technology had advanced such that it was possible to make a leap in video quality similar to the transition the record industry had gone through years before in converting from cassettes to compact discs (CDs). The CD quickly replaced the cassette when Phillips invented the digital encoding technology; the marketing thrust, and inevitably the driver in quick adoption, was that: (1) CDs were claimed to be indestructible (as opposed to cassettes, where the tape could get caught, jammed, or warped, permanently ruining the copy); (2) the sound quality emanating from digital encoding was a quantum leap forward from analog tape; and (3) CDs were smaller and therefore more portable than 12-inch vinyl records. While the random access convenience of just jumping from song to song on a CD was compelling (as opposed to fast-forwarding or rewinding), the notion of having a portable, near-perfect hiss-free and non-degradable crystal clear copy of music persuaded consumers. Sometimes, with technology, there truly is a better product, and CDs were a case in point.

I have digressed into the record business because the same forces were aligned against videocassettes. Different consortiums of motion picture studios, teamed with various consumer electronics manufacturers (e.g., Toshiba, Matsushita), pioneering DVD technology. They believed that the DVD offered the similar quantum leap from digital to analog quality that consumers had so overwhelmingly embraced in the record industry when moving from cassettes to CDs. As in the early days of the video-cassette, where format wars erupted between the Betamax and VHS formats, similar format wars took place on the DVD battlefront. Matsushita, the Japanese consumer electronics company (Panasonic brand) that had pioneered the VHS format and acquired Universal Studios (only to later divest majority ownership in a sale to Seagrams) was supporting one standard, whereas Toshiba and Warners were supporting another.

An entire chapter could be written about these format wars, but suffice it to say that given the investment, historical fallout from prior format disputes, and the potential market size, the studios banded together to “adopt” a format.

How Does a DVD Work?

The underlying technology of DVDs is compression, or the ability to take a huge amount of data and store it efficiently. Accordingly, there is a level of randomness, since there is a direct relationship between the amount of data stored and the end quality; the more information, the better the resulting output quality. The inherent problem concerning compression for DVDs is that the amount of information that needs to be processed for a moving picture is staggering relative to an audio file. For a movie, each frame needs to be stored, including all the elements, ranging from backgrounds, to characters, to colors, shading, audio, etc.

The quantity of pixels that need to be reduced to digital 0s and 1s to compress a color film image was, in fact, too great to fit onto a disc, which was a driving technical hurdle preventing the invention of a disc or technology that could mimic a CD for film. The breakthrough came with the notion of looking at the differences between frames and only storing the differences; in this way, the amount of data that needed to be converted and stored was dramatically reduced. DVD compression actually “cheats” by omitting data. The compression digitizes and stores new elements, but in terms of going from frame to frame, only differences need to be kept. This efficiency trick, combined with massively greater storage/data capacity compared to a CD, enabled compression of sufficient data to allow a typical film to fit on a single DVD disc.

Early Stages of the DVD: Piracy Concerns, Parallel Imports and the Warners Factor

At the Consumer Electronic Shows of the mid 1990s, gawkers and industry executives watching DVD demonstrations could intuitively grasp the leap in quality. DVD pictures were undoubtedly better, and the DVD offered the same type of ancillary upgrades to consumers that the CD had offered. Videotape often got stuck in machines, and DVDs eliminated those concerns, and were marketed with an aura of discs being “ultimate” and “permanent” (no one was talking about scratches, of course). Another user-friendly element was the elimination of having to rewind a tape. Rewinding a tape at the end of a movie is a universal nuisance, and some video rental stores even charged penalties if tapes were returned unwound. With a DVD, when the movie ended, you just hit a button—no rewinding, no hassle. As silly as it may sound, consumer market research regularly found the elimination of having to rewind as one of the most significant benefits of a DVD, which was statistically on par with the improved picture quality. Never overestimate the consumer!

A better mousetrap does not guarantee adoption, and in the case of the DVD, adoption was further hampered by studios’ reluctance to market and sell properties on the new format: virtually all major studio executives recognized the benefits of the DVD, but concerns over piracy and parallel imports were sufficient barriers to move slowly, if at all.

The following was the cost-benefit matrix of the time:

Costs/Negatives:

■ expenses to encourage consumer adoption

■ need to manage duplicate inventories (video and DVD)

■ piracy—DVDs held the potential of people making perfect digital copies

■ parallel imports (see later discussion)

Benefits:

■ better quality and durability

■ favorable user-friendly features (e.g., no rewind)

■ smaller packaging needs

■ less expensive manufacturing costs, therefore higher margins

■ ability to turnover library/catalog product by selling new format

Despite the apparent edge to the benefits, the inherent nature of the DVD as a perfect digital copy created significant anxiety at the studios. Intellectual property is the lifeblood of the system, and while video piracy was always a key concern, that concern heightened with digital copies. If just one person were able to make copies from a DVD, then, in theory, a pirate could have access to a digital master and illegally distribute perfect copies into the marketplace. This had the potential of undermining franchises, new releases, and entire studio libraries. The risk was simply too high, and until sufficient security was implemented most studios held back DVD releases of new titles (another form of windowing).

Adding to the problem was a concern about parallel imports. While it is commonplace to theatrically release a major movie on the same date worldwide (day-and-date release, as discussed in Chapter 4), this was rare to nonexistent back in the mid 1990s when DVDs were first introduced to the market. Parallel imports means buying goods in one territory and importing them into another. For example, if a movie were released in May in the United States, it might be planned for a release in Europe or Asia at Christmas, the same time the DVD of the title would be coming out in the United States. There was nothing to prevent a retailer from buying quantities of the DVDs in the United States and importing them to the market where the movie was just releasing in the theaters, or worse, in advance of the theatrical release. What would happen if consumers could view (or worse, obtain) a perfect copy of the movie before it was even released in theaters? The potential of parallel imports had always existed, but, like piracy, the quality of digital copies heightened people’s fears. The box office revenues in international territories were growing consistently, and the theatrical release was too important a driver of the entire studio system to risk.

A key strategy to combat this practice and enable the broader introduction of DVDs was the implementation of regional encoding. This was a process devised by the studios where DVD machines and related DVD software would only work within specific territorial boundaries. For example, a chip would be placed in a machine telling it that it was a “European” encoded player, and this player would only play a disc encoded as European. If you put a disc from the United States (encoded as a United States disc) into a European player, the codes would not match and the disc would not play. The studios managed to gain acceptance from consumer electronics companies manufacturing players (likely helped by Matsushita’s relationship with Universal and Sony’s ownership of a Hollywood major), and all parties agreed to a worldwide map.

Interestingly, regional encoding is akin to a form of hardware-based digital rights management (DRM), and was instituted to restrict how and where a consumer could play back a copy. Conceptually, DRM systems enable the same type of restrictions, but further open up a panoply of options down to managing how many times a product may be played on a specific machine (or overall). Regional encoding is still enforced today, and software bought in one territory will not play on a machine manufactured and sold in a different region. For those wanting to defeat the system, region-free players (which will play a disc regardless of which region it is encoded to) are available, but obviously for a premium price.

The net result of these fears, regarding piracy and the potential of undermining carefully orchestrated release windows, was that most studios were not releasing any titles on DVDs. Those studios that were entering the market were dabbling with older catalog titles where there was obviously no risk to current theatrical release. Sound familiar today? Again, history repeats itself, and the adoption of downloads or over-the-top releases of premium product and vesions (e.g, HD versions) has been slowed by fears of pirating a perfect digital copy (just like the introduction of the DVD); accordingly, content owners often lead with catalog titles to mitigate the risk.

One exception to this initial reluctance to release a broad array of titles on DVD was Warner Bros. The president of Warner Home Video, Warren Lieberfarb, was among the earliest and most vocal proponents of DVD technology. Warners invested in a DVD authoring and replication facility, and simply believed that the DVD was such a superior technology that it was inevitable consumers would adopt the platform (not to mention the benefit of holding several related patents). For pioneering the technology, and championing its introduction against naysayers and those who wanted to delay launching, Warren Lieberfarb has been called “the father of DVD.” Even within an incredibly competitive industry, people acknowledge Warners’ leadership position as the catalyst for the transition to DVD from video. Most people forget, or were oblivious to, the significant risks to protection and window management of vital intellectual property assets that stalled and almost prevented the introduction of DVDs.

Influence of Computers: Cross-Platform Use of DVDs Speeds Adoption

One significant factor in the acceleration of DVD penetration was the crossover between consumer electronics players and computers. DVDs had an exponential increase in storage capacity versus floppy discs and CDs. (Note: A standard DVD holding a two-hour movie plus customary ancillary value-added materials (VAM) has roughly 9 GB of content, while Blu-ray boasts an increase to 50 GB.)8

As DVD drives slowly replaced other storage mediums on PCs, it was only a matter of time for convergence to take place. With a common software medium, consumers could store data, download pictures and music, and watch movies all with DVDs. Further, this convergence dovetailed with the increased penetration of laptop computers. It was now possible to bring a DVD of a movie on your laptop for a plane ride, jumping between spreadsheets and entertainment. History would repeat itself once again, with integrated systems used to drive adoption—Sony included Blu-ray players with its next-generation PlayStation 3 console system, hoping the consumer electronics product (this time a games system rather than a PC) would help drive adoption.

Recordable DVDs and Perceived Threats from Copying and Downloading

Once it became clear that DVDs were the medium of the future and would replace VHS cassettes, the next obstacle was the ability to record. For the same reasons that slowed the introduction of the DVD, piracy and economic fears tied to the ability to make digital copies, a recordable feature was delayed in the marketplace. It was one thing to allow a DVD, but the dangers ultimately seemed manageable without the ability of the consumer to burn copies of movies. As an accommodation to the concerns of the studios, the major consumer electronics manufacturers launched play-only DVD machines; when compared to the complexity of regional encoding, this was a relatively easy measure to assuage the software distributors.

Over time, however, pressures for recordable players overwhelmed this protectionist direction; moreover, the consumer electronics industry was not in a position to stop the computer manufacturers from deploying recordable drives. Memory and storage is the mantra of the personal computer industry, and computer manufacturers were inclined to encourage data storage rather than impede it. Whether music or digital camera/pictures, the new applications were growing at breakneck speed. It was unrealistic to expect that DVDs could record everything but visual entertainment software.

Giving the studios solace in terms of DVD burners becoming a standard accessory was the fact that movies are not easy to copy. The amount of data compressed is staggering, and it is cumbersome and complicated to copy a movie relative to a business file or music CD. Moreover, anti-copying mechanisms are encoded on films preventing the simple copying of a movie on DVD. The larger fear is the Internet, and while lengthy download times for movies (hours rather than minutes) seemed initially to pose a significant enough hurdle to give distributors comfort, technology again advanced and P2P file sharing exposed the underlying fear that had loomed with digital copies since the advent of DVDs.

At first, digital rights management systems (and the lure of new revenue streams) seemed to have progressed quickly enough to temper those fears and promise significant and ongoing roadblocks to the easy pirating of copies; however, it was this backdrop that caused the studios to take a strong stand in the Grokster case when the ability of P2P services demonstrated facility and scale for making pirate copies. This created the biggest challenge to the industry since the enabling Sony v. Universal case roughly 20 years before. (Note: See Chapter 2 for discussion of file sharing, P2P downloading technology, and the Grokster case in terms of the relationship to piracy and digital downloading.)

Intermediate Formats: Laserdiscs and VCDs

Finally, it is worth mentioning that, as in most areas of technology, there were intermediate steps between VHS and DVD adoption. Some may remember the laserdisc, which was dominated by companies such as Pioneer. Laserdiscs were about the size of an old phonographic record and had better clarity and durability than standard VHS tape; they were, accordingly, priced higher, and the early adopter videophiles built up collections of laserdiscs. Laserdiscs were still, however, based on analog technology and were ultimately doomed with the advent of the digital age. Consumers that always wanted the best available technology/presentation of the time built up collections, but the life of laserdiscs was comparatively short and the penetration of the hardware players relatively limited when compared with the mass-market adoption of both VHS and DVD and then Blu-ray.

Similarly, in Asia, and in particular Southeast Asia, a market grew up for video CDs (VCDs). These are CD size and look like DVDs, but simply have inferior compression and memory, and accordingly inferior picture quality. VCD distribution grew quickly in markets rife with piracy, and a consumer could usually find a low-quality and unauthorized version of virtually all studio blockbusters on VCD in the local markets. Because penetration grew quickly, it took some time for DVDs to supplant this market. However, with VCDs and laserdiscs both intermediate and inferior products to DVDs, these formats began to quickly diseppear; in fact, I suspect most readers of this book will never have heard of them.

Revenue Sharing—Consequence of a Hybrid Market and Aid to DVD Adoption

Revenue-sharing arrangements took off in the late 1990s. This was a scheme where the major studios gave the major video rental chains, such as Blockbuster and Hollywood Video, their titles on a consignment basis. Rather than charge $29–40 for a title, the studios deferred the upfront revenue in favor of a split of rental income. Although deals differed, it was reputed that a rule of thumb granted the studios 60 percent of the revenue from rental transactions; moreover, once a title had been past its peak release period, excess inventory was sold in-store ($5–15 range), with the proceeds shared between the distributor and rental chain.

Some have theorized that the introduction of revenue sharing was a gambit to increase DVD penetration, as the studios encouraged the shift away from VHS (in fact, some former video division heads have alleged just this tactic).

Once DVD penetration had hit mass-market levels, prices started coming down for both players and new release titles and revenue-sharing schemes waned. The Hollywood Reporter cited these factors and attributed the decline in revenue sharing to the increase of the consumer purchase market at the expense of the video rental store:

… Once DVD hardware market penetration reached about 50 million players in U.S. households by 2002, WHV and other major Hollywood studios began ratcheting down their rental revenue-sharing participation, while aggressively discounting the wholesale and retail price of movies on DVD. The new popularity of DVD, combined with low-priced hit new releases and classic catalog product, energized consumer spending on home videos, resulting in a national average household buy rate of 15 DVDs a year at an estimated price point of $19 or more each. That consumer action translated into triple-digit revenue gains at the studios. At the same time, the paradigm shift had reduced in-store foot traffic at video rental outlets nationwide, taking a huge bite out of gross consumer spending on movie rentals.9

Beyond an Ancillary Market: Emergence of the Made-for-Video Market

Direct-to-Video and Made-for-Video Markets

As video matured, and retail points of sale expanded, it became clear that there was an opportunity to release new/original product directly to the video consumer.

Paralleling the growth of the video market overall, the natural target base was the consumer buying the seemingly dizzying number of Disney videos. If it were possible to sell over 10 million copies of a movie such as The Lion King or Beauty and the Beast, would the same consumer buy a branded property that was not released in the theaters and was instead an original property for the home video market? With the benefit of hindsight, clearly the answer is yes. The simplest and most successful path was to create sequel properties. Disney perfected this almost to an art, and empowered a specific division focused on producing spin-offs. Examples of “video sequels” or spin-offs during this video renaissance included:

■ The Return of Jafar (1994)

■ Aladdin and the King of Thieves (1996)

■ Beauty and the Beast: The Enchanted Christmas (1997)

■ Pocahontas II: Journey to a New World (1998)

■ The Lion King 2: Simba’s Pride (1998)

■ Hercules: Zero to Hero (1998)

■ The Little Mermaid II: Return to the Sea (2000)

■ Lady and the Tramp 2: Scamp’s Adventure (2001)

■ The Hunchback of Notre Dame II (2002)

■ Tarzan & Jane (2002)

■ 101 Dalmations 2: Patch’s London Adventure (2003)

■ The Jungle Book 2 (2003)

■ The Lion King 1½ (2004)

■ Mulan II (2005)

■ Tarzan II (2005)

■ The Fox and the Hound 2 (2006)10

Fox jumped on the bandwagon with titles such as FernGully 2: The Magical Rescue, as did Paramount, leveraging well-known characters and brands, such as Charlotte’s Web 2: Wilbur’s Great Adventure. Independents that had strong children’s properties expanded their brand. A prime example was Lyric Studios franchise Barney; in addition to taking television episodes to video, live Barney concerts were perfect fare to release on DVD.

Perhaps the most successful example of a made-for-video property came from Universal Studios. Universal had theatrically released a film called The Land Before Time, executive produced by George Lucas and Steven Spielberg, to moderate success. Recognizing the inherent appeal of the characters, children’s love of dinosaurs, and the franchise potential, Universal invested in video sequels. The Land Before Time franchise became so successful, and the potential for other made-for-videos was considered so high, that Universal created a new division called Universal Family and Home Entertainment. Headed by the former president of Universal’s video division, Louis Feola, Universal produced a series of animated (e.g., Balto: Wolf Quest) and live-action (e.g., Beethoven’s 3rd, Beethoven’s 4th, Beethoven’s 5th, Slap Shot 2: Breaking the Ice) properties under this banner. (Note: More current made-for-video titles include The Scorpion King 2 and the American Pie Presents sequels (Band Camp, The Naked Mile, Beta House), the latter of which are estimated to have sold 1–2 million copies each.)11 The Land Before Time property spawned more than 10 sequels, making it one of the most prolific and successful children’s franchises in the marketplace.

DVD as a Fallback Release Outlet

“Made-for-video” titles are often confused with releases that may otherwise go direct to video. A title such as The Land Before Time 3 is made for debut in the video market, but with the expense of marketing and releasing a theatrical film, studios soon realized that certain films that did not pan out as planned could go straight to video. This outlet developed into an important revenue stream, given that there are many films made that never see the light of day in theaters or may have a very limited theatrical release to brand them theatricals (or otherwise qualify them for pricing tiers downstream delineated by output deals that have a theatrical release tier threshold). Interestingly, this has developed as a two-way street: there are also instances of film produced for the video market that come out well, and the studio may subsequently elect to release them theatrically. It is often hard to pinpoint these titles, however, for the distributor will likely be reticent to publicize that the title was originally intended for the video market for fear of souring the caché value.

Niche and Non-Studio Direct-to-Videos/Made-for-Videos

In addition to mainstream videos, the opportunity in the video marketplace led to numerous niche opportunities. One of the strongest sectors was health and fitness/exercise. Swimsuit models and supermodels competed with the likes of Jane Fonda to release aerobic and other workout-related tapes.

Another burgeoning area was concert films. With the enhanced video and sound quality possible with DVDs, it became more attractive to sell a video from a concert tour or a specific performance to complement CD sales.

Finally, with the upside potential in the family/kids market, it was only a matter of time before toy companies capitalized on their key brands and expanded into the video market. Lego produced Bionicles, and Fox announced a partnership with Hasbro to produce and release titles based on several of its popular brands. I could go on and on talking about documentaries, music videos, and a variety of other genres, but the point is that DVDs opened up a new market for virtually all forms of content production.

Next-Generation DVDs: Blu-Ray versus HD-DVD—Format War Redux

In 2006, two new competing high-definition DVD systems were introduced pitting rival Japanese consumer electronics manufacturers against each other (again). Blu-ray, developed by Sony, and HD-DVD, developed by Toshiba, were pitted against each other, offering high-definition images (1080) and a remarkable amount of storage capacity (25–50 GB). Different partners lined up behind each, with Microsoft in the HD-DVD camp and a greater number of Hollywood studios (e.g., Disney and Fox) initially jumping on the Blu-ray bandwagon. Adoption was slow, however, as no parties wanted to be beholden to a format that might not win, the initial price points for players were high ($350+), and consumers were not convinced that the quality differential from standard DVDs warranted a pricey upgrade. Unlike earlier format wars, both sides tried to speed adoption by integrating the new players into other hardware: Sony including a Blu-ray player in each new PlayStation 3 game console, while Toshiba bundled its HD-DVD drives into notebook computers and Xbox 360 game systems.

It was a déjà vu scenario, with full-scale war between two major Japanese consumer electronics companies, billions of dollars potentially at stake, and the consumer caught in the middle, waiting out the format winner. With both sides having sold approximately 1 million units by the end of 2007, there seemed no clear winner in sight, and headlines abounded. This one was seen in the International Herald Tribune on New Year’s Day 2008, just days before the annual mass gathering at the consumer electronics show in Las Vegas: “The Format Wars: Titans Stuck in a Stalemate—Despite Months of Tussling, No Clear Winner Has Emerged in the Battle Between Blu-ray and HD-DVD.”12 I was even part of the prior lobbying efforts, with studio partners and other vested parties alike courting Lucasfilm for an endorsement. What do you do when you have different franchises with different studios, and you do not know who may distribute your next film or TV series?

Then, suddenly everything changed and the battle was literally over. In February 2008, Warner Bros., the pioneer in traditional DVD, had been on the fence and then came out in favor of Blu-ray; within the same week or so, Walmart came out and announced it would no longer stock HD-DVDs or HD-DVD players. With the market share leader for DVD sales at retail and Warners both coming out in favor of Blu-ray, it shocked the market, and Toshiba pulled out.13 No doubt, there was growing fear that delay could doom the entire industry, and if all the studios did not start lining up behind a common format, the danger existed that high definition would miss its window and be bypassed entirely by the growing download markets, akin to CDs being replaced by digital files.14 In a sense, as typical with the introduction of new technology in the media, one battle had ended and another was just beginning.

Finally, one feature of Blu-ray put the physical media on a path to embrace the Internet—perhaps consciously designed to ensure a place working within the new Internet world rather than having to simply compete against it. “Blu-ray live” enables an interactive feature that allows viewers to simultaneously watch a film along with its director, seeing commentary and chat live while the movie is playing. Among the first tests of this component was an invitation to watch The Dark Knight along with its director, Christopher Nolan, and reportedly up to 100,000 people were supposed to be able to watch along together.

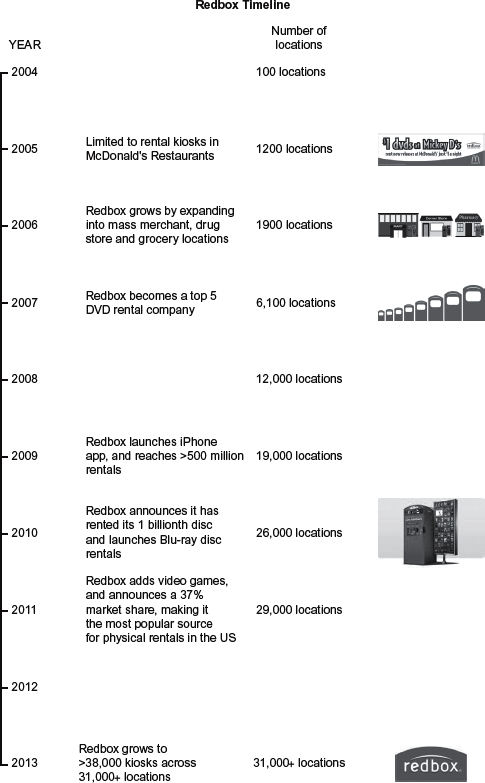

Blu-ray is providing industry optimism after years of decline in the video industry—growing by roughly 20 percent in 2011, cresting $2 billion for the first time, and then seeing a 13 percent sales increase through the first half of 2012, Blu-ray sales are now material and mass market.15 Part of the growth has been organic, but industry insiders acknowledge that Avatar helped fuel the growth, with Blu-ray sales of the film reaching 11 million units worldwide. With this market penetration, by the end of the third quarter, 2011 revenues from Blu-ray sales for the first time surpassed revenues from rental kiosks ($423 million for Q3 2011 from Blu-ray versus approximately $414 million from kiosk rentals).16 This was extremely good news for the video industry, because margins tend to be higher from the sale of retail products than from rentals, and the only material growth in the prior few years had been from low-cost rentals, including, most importantly, Netflix and Redbox (see below for further discussion). Despite all this positive spin, it is important to put Blu-ray in context, as the increase in Blu-ray has been more than offset in declines in traditional DVD sales.

In addition to the general video window of releasing a movie six months or so after theatrical release, it became economical to market other product at retail. Two major categories were exploited: catalog titles and television shows. As for catalog, every studio has a group of classics in its library, whether themed to stars (Betty Davis collection), awards (Oscar winners), or simply “classics.”

When releasing these films, the practice of having the producer, or more often the director, create a special edition (e.g., director’s cut) evolved. This could entail releasing an extended version of the film or re-editing parts that may have been cut out for theatrical release (often dealing with time constraints that did not apply to home viewing). Additionally, in some instances special editions would “clean up” elements in the master, given advanced technology (e.g., remastering, taking advantage of computer cleanup or digital sound), and in other cases the creator may have even produced new elements and re-edited the films. When George Lucas released the original Star Wars movies (A New Hope, The Empire Strikes Back, and Return of the Jedi) on DVD for the first time in 2004, all of these elements came into play: (1) all of the movies went through extensive cleanup, utilizing a computer digital restoration facility; (2) all of the movies included remastering sound elements; and (3) a few new elements were introduced, utilizing special effects to alter select sequences.

Another growth area was releasing “seasons” of television series. This became popular, initially, with longstanding hits such as The Simpsons, as well as fare that had developed a strong following on limited services such as pay TV but had not been exposed to a larger audience. HBO titles are a perfect example. Consumers that were aware of a show such as The Sopranos or Sex and the City but did not subscribe to HBO could rent entire seasons and watch them like a miniseries.

Soon, collections became the rule rather than the exception, and full seasons of top TV shows could be found on shelves: Alias from ABC, 24 from Fox, and the complete Seinfeld. By Christmas 2004, box sets abounded at retail, so much so that video distributors and retailers for the first time started worrying about saturation and how far the market could expand. Collections, special editions, etc. are all further illustrations of Ulin’s Rule—distribution maximizes revenues through repeat consumption opportunities, tied to differential pricing and timing.

Maturation of the DVD Market and Growing Complexity of Retail Marketing

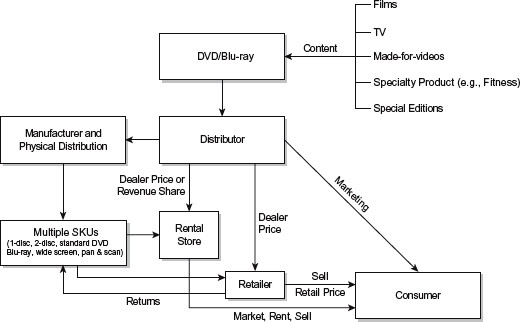

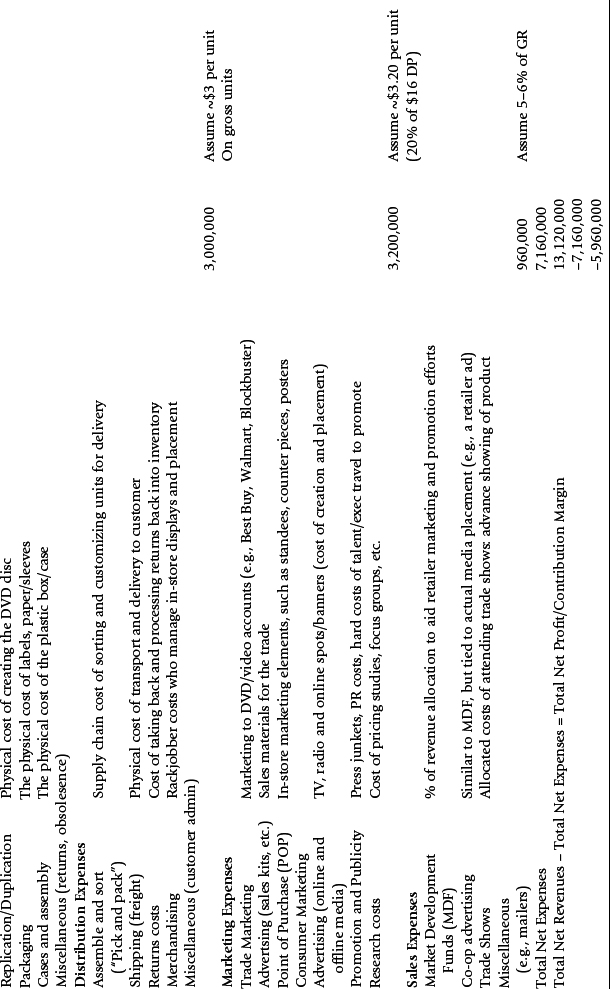

The DVD/Blu-ray/video supply chain, being tied to a physical consumer product, is far more complicated than the chain of licensing and delivery of movies and TV shows, respectively, to theaters and broadcasters. Figure 5.2 exhibits the key components of assimilating a variety of content into a product distributed in multiple SKUs and formats to outlets of fundamentally different character (rental versus sale), and marketed to the customer by both the distributor and point-of-purchase retailer.

Peaking of the DVD Curve and Compressed Sales Cycle

By the late 1990s, it was clear that DVDs were the format of the future, and in the ensuing years literally exploded. Growing from less than 10 percent in 1999, by the end of 2006 penetration exceeded 80 percent and had bypassed VCR penetration.17 By 2003, annual DVD rental revenues exceeded VHS revenues,18 and by 2005 the number of VHS units of a major title relative to DVD units was negligible. In fact, by 2005 many titles, such as Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith, were released only on DVD.

Figure 5.2 Complexity of DVD/Blu-ray Supply Chain

With the growth of DVD, the balance between rental and sell-through started to shift dramatically toward sell-through. The durability and quality of DVDs, together with the ability to include special features (see discussion regarding VAM), made them ideal retail items, as well as perfect gifts. All of a sudden, it was not just Disney selling huge numbers of children’s videos, but key titles from all studios were selling in the millions. And for children’s properties, the numbers simply kept growing. Shrek, released in 2001, reportedly sold 2.5 million units in its first three days19 en route to selling upwards of 20–30 million units worldwide, as did Disney–Pixar’s Finding Nemo.

Depending on whose statistics one believes, the DVD/video market peaked somewhere between 2004 and 2006, and by the end of 2005 it was evident that the market was entering into a phase of decline, both on a by-title basis as well as overall. Given the size and importance of the home entertainment market in the media sector, this was massmarket news, as USA Today highlighted: “For the first time in home video’s nearly 30-year history, sales and rentals slipped in 2005 as slowing growth of DVDs couldn’t overcome falling prices and a dying VHS market.”20

While, historically, home video revenue from most blockbusters equaled or surpassed that of their box office take, the trend seemed to have peaked. Describing the drop in conversion rate—the ratio of video sales to theatrical—Variety reported that the theatrical gross exceeded the DVD revenues of films such as Batman Begins and War of the Worlds (e.g., Batman Begins video revenues $170 million versus $205 million theatrical gross).21 There has been a continuing decline in the DVD market ever since this peak22 and, as noted and demonstrated by comparing Figures 1.5 and 5.1 (studio revenue breakdown in 2007 vs. 2012), the impact has been a steep fall in terms of the percentage of the overall studio revenue pie attributable to the video market (down to 30.4 percent from 48.3 percent). 2008 typifies the dramatic nature of the falloff, when there was a precipitous drop in new release volumes, estimated to be down close to 20 percent.23 Illustrating the severity of the decline on a by-title basis over almost a decade, Table 5.3 lists the top-selling DVDs for 2003 versus 2008 and 2011 in the United States.

Given the overall importance of DVDs to the studio revenue base and ecosystem, this pace of decline continues to set off alarm bells; the cause can no longer be attributed solely to a recessionary climate, and the shift is putting even more emphasis on the future of electronic sell-through, subscription streaming, and other new consumption patterns in the digital space.

Compressed Sales Cycle

The other factor impacting the market maturation was an increasingly compressed sales cycle. This has been accentuated by the flood of additional product trying to take advantage of DVD dollars. Whereas only a few years earlier shelf space competition was between different hit movies, the largest growth sector became TV product and box sets; with a glut of new and catalog TV releases, together with made-for-DVD product, competition became fiercer, shelf space turned over more quickly, and sales cycles compressed. In a sense, the DVD retail cycle was beginning to mimic the box office, with revenues more front-loaded by the year, and films earning the majority of their video revenues within the first two weeks of release.24 In fact, most studios acknowledge that the majority of sales on a title now come in this short period. The Wall Street Journal highlighted this shift: “a typical DVD release would rack up about one third of its total sales during the first week of release; the figure was even lower for animated movies, which tended to have longer legs. DVD sales would then steadily mount over weeks or months. But these days, DVD releases are generating a huge percentage of their total sales—typically over 50 percent and in some cases, up to 70 percent—in the first week.”25

Table 5.3 Top Five DVDs of 2003, 2008, and 2011

Studio |

Title |

Date |

Units |

Disney |

Finding Nemo |

2003 |

26,000 |

New Line |

The Lord of The Rings: The Two Towers |

2003 |

21,050 |

Disney |

Pirates of the Caribbean: Curse of the Black Pearl |

2003 |

19,450 |

Warner Bros. |

The Matrix Reloaded |

2003 |

15,520 |

Universal |

Bruce Almighty |

2003 |

12,650 |

Warner Bros. |

The Dark Knight |

2008 |

12,385 |

Paramount |

Iron Man |

2008 |

11,375 |

Fox |

Alvin and the Chipmunks |

2008 |

10,560 |

Warner Bros. |

I Am Legend |

2008 |

10,125 |

DreamWorks Animation |

Kung Fu Panda |

2008 |

9,750 |

Warner Bros. |

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 1 |

2011 |

8,565 |

Disney |

Tangled |

2011 |

7,635 |

Warner Bros. |

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2 |

2011 |

7,065 |

Disney |

Cars 2 |

2011 |

5,340 |

Universal |

Bridesmaids |

2011 |

4,695 |

Notes: Units are projected lifetime shipments of the film on home video.

© 2012 SNL Kagan, a division of SNL Financial LC, analysis of video and movie industry data and estimates. All rights reserved.

This trend developed outside the pressures of new media, making the issue of how to window downloads that much more complicated. The DVD cash cow was set for a reversal of fortune, and no studio wanted to accelerate that trend. Unless downloads could be proven to add incremental value, let alone not cannibalize DVD, there was little impetus to experiment with key new releases.

Expansion of Retail Mass-Market Chains: Walmart, Best Buy, Target, etc.

Routinely selling more than 5 million copies of an A-title and, on occasion, over 10 million copies of select hit children’s/family titles could only occur with the expansion of retail distribution. Video rental stores jumped on the bandwagon as a point of sale for DVDs, but their bread and butter remained rental, and the vast majority of sales took place at mass-market retailers.

Because DVDs as a software entertainment commodity offered a unique product with each release (as does a CD or video game), both suppliers and retailers quickly realized the marketing opportunities. Not only could DVDs sell in record numbers, but DVDs could actually drive consumer traffic into stores. If the next Star Wars or The Lord of the Rings movie were being released on DVD, customers would crash stores in droves. It was like Christmas time with each new major release.

Of course, nothing is that simple, and greater sales and expectations were also driven by increased marketing. To sell several million copies of a title, it is necessary to advertise the release, and advertising budgets for DVD releases multiplied several-fold. Studio video divisions became expert at running sophisticated P&L models, trying to gauge the saturation threshold after which increased marketing spend would not yield additional positive contribution margin.

Increased marketing expenditure could ultimately only be justified with concomitant retail support. Accordingly, retailers went through a maturation period as well, with more shelf space dedicated to DVDs. In-store marketing campaigns grew in importance, with dedicated instore display packs, such as towers themed with images from the movie, adding additional capacity during a title’s initial release. Executing a compelling in-store campaign involves elements including:

■ posters

■ additional signage

■ stand-alone themed display towers

■ placement of stand-alone displays and regular shelf placement (e.g., on new release end caps versus off-the-aisle placement)

■ employee education

■ in-store trailers

■ dedicated retailer advertising

■ trade advertisements

■ store circulars in newspapers, etc

To achieve this type of coordinated campaign at retail, several economic incentives evolved. Industry practice developed such that studios offered an allowance for both market development and cooperative spending. Typically, studios will allow retailers to spend a small percentage of the wholesale revenue against their marketing costs directly related to the title. Additionally, studios will allow another line item for cooperative advertising expenditure. Where these lines are drawn is a bit fuzzy, with cooperative advertising a bit easier to track, in that it is supposed to be allocated for actual advertising, whether print media, radio, or television. Cumulatively, a retailer may have a few percent of actual wholesale revenue to apply against its costs in advertising, marketing, and merchandising the title.