Marketing and distribution work hand in hand (or at least they should), with the line often fuzzy. Technically, distribution involves the sales, physical manufacture (or access, if online), and delivery of goods for sale, such as a film print, DVD/Blu-ray disc, television master, or electronic copy. For each category of media that a piece of intellectual property is licensed, distribution addresses how it is consumed and monetized: what the price is, where and how the product is sold (or leased), when the title is available, how many units are being made, how inventory is managed, and what the costs of goods are. Marketing, in contrast, focuses on awareness and interest. Marketing is, to some measure, the business and art of driving a consumer to consumption by making him or her aware that the good is available and creating the impulse to watch, buy, or borrow it. In summary, as noted in Chapter 1, marketing focuses on awareness and driving consumption, whereas distribution focuses on maximizing and making that consumption profitable.

In Chapter 3, I discussed the problem of predicting the success of a film or TV show (i.e., experience goods), given the factors of imperfect information, cascades, and infinite variety. While it may not be possible to predict the outcome, marketing, by its nature, is an attempt to influence the outcome. Accordingly, marketing comes to the rescue of the experience good quandary and tries to put some experience into that good; the viewer, without having actually consumed the end product (which, per an experience good, is the only way to know whether you really like/want it), is helped to make up his or her own mind.

Marketing through trailers, posters, press, reviews, websites, social networking posts, seeded blogs, advertising, etc. is bombarding the consumer with inputs to influence the selection of a film, TV show, or video in an environment stacked with an infinite variety of creative product. And the most effective marketing may be that which makes you feel you have already (to a degree) experienced the film/show. If a trailer is a microcosm of the experience, and the trailer is well directed to a consumer demographic, then it may seduce that target consumer to see the film, explaining, in part, the unique frustration of having felt hoodwinked if the movie did not fulfil the expectations engendered by the trailer signal.

Accordingly, beyond marketing helping to build a brand for distribution windows, it is interesting also to view these activities in the economic context of differentiating information inputs; those inputs, heavily influenced by marketing, are uniquely important in selecting a product you cannot know whether you will like until you have “consumed” it.

It is further interesting to speculate how the online world will impact these traditional patterns and the positioning of inputs. Is there a difference in utilizing Rotten Tomatoes (www.rottentomatoes.com), which accumulates all critics’ picks into a single scorecard—does “fresh” (greater than 50 percent positive reviews) really mean it is a good picture, or are variations and cascades baked into the equation such that you have no better reference from the overall verdict versus an individual critic where you have sorted out an internal mechanism to map their biases onto your own? Do social networking sites, where you affiliate with friends and recommend “liked” programs, provide a better predictor and negate cascade behavior or do they exacerbate the problem? Do recommendation engines really work to defeat the inherent uncertainty in consuming an experience good, and do references to “others who bought X also bought Y” further work to defeat the risk of unwisely committing one’s time? In the media and entertainment industry, the online world is making the whole concept of marketing a lot more entertaining.

Marketing strategy is impacted by several factors, including the budget, target audience (demographics), timing, talent involved, and partners.

Budget Tied to Type and Breadth of Release: Limited Openings, Niche Marketing, and the Web’s Viral Power

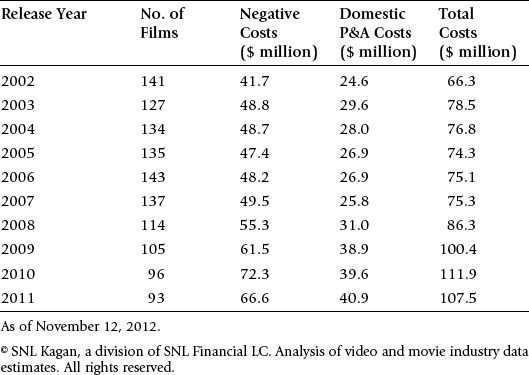

For a film, the marketing budget is the most significant cost item outside of making the picture. While there is no exact rule, it is common for the marketing budget (inclusive of prints and advertising) to equal a significant percentage of the cost of producing the film. A film that costs $75 million may, for example, have a domestic marketing budget of $35 million or more (see Table 9.5), inclusive of the following line items:

■ media/advertising

■ PR

■ website

■ social media site (e.g., Facebook page)

■ travel.

As discussed in Chapter 4, the amount spent to open a film is disproportionately large because the theatrical launch of a film is the engine that drives all downstream revenues. Accordingly, the money spent up front marketing a film, creating awareness, develops an overnight brand that is then sustained and managed, in most instances, for more than a decade. In extreme cases, marketing costs can equal or exceed production costs. The Wall Street Journal noted of the March 2009 release of Monsters vs Aliens, which was trying to expand the market for 3D films: “DreamWorks Animation spent upwards of $175 million to market the film globally, more than the $165 million the studio used to make the movie.”1

Word-of-Mouth Limited Openings and Niche Marketing

Not all films, of course, can sustain a marketing budget in the tens of millions of dollars, which forces distributors/studios to employ a variety of strategies for launch (see also Chapter 4 and the section on “Press and PR”, page 523). One strategy is not to open a film in a wide, big bang fashion. Opening a film in a nationwide and worldwide manner is the most expensive avenue, requiring national media and costs that make the launch an event. As touched on in Chapter 4, if a picture is opened in limited release, targeting critics and key cities and hoping that reviews and word of mouth will create momentum, the costs are dramatically reduced. This is a typical pattern for art-type movies, films trying to attract critical acclaim leading to award consideration (e.g., Zero Dark Thirty), and movies that may appeal to an intellectual base (e.g., Woody Allen), where openings in, for example, New York, Los Angeles, and a few other select locales will draw avid moviegoers and start creating buzz. The risk factor with a staged release pattern, as discussed earlier, is that the reviews or performance will not meet expectations and the film could struggle to gain a wide release (that perhaps could have been achieved if the movie opened day-and-date nationwide)—a risk that tends to be exacerbated by online and mobile sources virally spreading reactions.

Another strategy to open a film with limited marketing dollars is to focus on niche marketing. A perfect example of niche marketing is campaigns targeted at colleges. Distributors will try to tie up with local on-campus film groups, etc. to get the message out on a film that they believe will appeal to this demographic. These types of campaigns can include posters, Internet components, sponsored events with film clubs, etc.

Sometimes niche campaigns may be referred to as “underground campaigns” or “guerilla marketing,” which by their very nature can be difficult to orchestrate. There is a bit of inherent hypocrisy for a studio to try to stimulate a grass-roots campaign with an expressed goal of creating a hip factor. This is because what the studio is doing is seeding a bit of money to try to create a groundswell while really saving money. (Note: This generalization is a bit unfair, as given the profile of the niche film in question and resources, there probably is little money available for marketing; nevertheless, perception matters, and studios, as the masters of perception, could be accused of an end run even if, under the circumstances, they may be orchestrating the most viable strategy.)

As a component of a lower-budget campaign, viral campaigns are becoming more popular. These are Internet-driven campaigns using websites, blogs, and teasers. The goal of these campaigns is that the film or an element within it will simply “catch on.” One of the most frequently cited examples is The Blair Witch Project, a low-budget film that leveraged viral marketing to garner $140 million at the U.S. box office.2 Lots of people like to point to The Blair Witch Project as proof of a strategy, but seldom is it mentioned that the odds of success here are no better than in other areas; namely, there are many more wannabes than Blair Witch successes.

Is Viral Messaging on the Web Always a Good Idea?

In the zeal to point out that the Internet’s democratization of access affords a platform where anyone can have a shot, it is easy to forget that the Web is the essence of clutter. Gaining impressions and buzz amid the infinite choices online may actually be a longer shot statistically than a low-budget grass-roots campaign. The intersection of execution and luck is not magically better online. Additionally, while there are certain tricks of the trade and optimization strategies that can be employed, any viral campaign ultimately relies on sharing and peer-to-peer excitement. Moreover, in this context, “messaging” is no longer captive, and online users, unabashed in giving opinions and feedback, can be brutal. It is hard to control spin once material is unleashed into the blogosphere, and any campaign needs to be careful about opinion potentially turning negative. There is no guarantee that positive comments, downloads, and buzz will materialize, and as people continue to learn and experiment, this avenue could be a risky awareness strategy (even if compelling) when compared to a traditional media blitz.

Shift of Dollars to Online Tempered by Market Still Evolving

Despite these risks, the Web is no doubt a boon to marketers, and money spent to stimulate viral buzz is both tempting and often productive; moreover, the Web allows unique targeted marketing, and as technology and advertisers become more sophisticated, more dollars will shift online, given the inherent efficiencies of better-matching expenditures and messaging to narrowly defined consumers. As the shift in marketing dollars suggests, this is already happening. However, until Internet spending grows exponentially from its current levels, it will still be dwarfed by traditional media spends.

Further, the world of online is still evolving (with new formats available, and video advertising strategies continually being tested), and creative breakthrough ads are challenging; generally speaking, as of today, online (including social media and mobile) marketing alone still cannot create mass awareness.

Timing, Seasonality, and Influencing External and Internal Factors

Timing of a campaign is critical, and again it depends on several moving parts. Sometimes, it can be an effective strategy to say very little, allowing symbolism and mystery to create interest. One of the best examples of this was the 1989 release of the first Batman movie, starring Michael Keaton and Jack Nicholson. Months before the release, the Batman logo/symbol was simply plastered around the world: consumers could see it on posters, on buses, and on phone booths in London.

I asked Michael Uslan, who launched the Batman film franchise and has served as executive producer of all of the Batman films (including, most recently, The Dark Knight Rises), how he had seen marketing evolve in almost 25 years between the first Batman and the summer 2012 The Dark Knight Rises, and in particular how the Internet was influencing campaigns. He noted:

When our first, revolutionary Batman film was released in the summer of 1989 by Warner Bros., I considered it the best-marketed film in history. In New York City, you could not walk one block without running into someone wearing a Batman T-shirt or hat. That iconic black-and-gold bat symbol was everywhere. Movie posters were being stolen from bus shelters and theater lobby displays. People were paying to walk into movies showing the Batman trailer, then leaving before whatever feature was playing came on. Pirates were selling that brief trailer at comic book conventions for $25 a pop. When the Berlin Wall came down, kids were coming through to freedom already wearing Batman caps. But marketing via an Internet strategy didn’t exist. Today, it’s completely different. You cannot successfully and fully market any comic book or similar genre movie in this day and age without a viral campaign on the Net starting 10 months to a year prior to release if your intention is to build a franchise and market a brand. The Dark Knight had, perhaps, the best viral campaign ever. Fans of comics, movies, science fiction and fantasy, manga and anime, animation, horror, etc. must be engaged early on and “courted,” for they have the capability to make or break a movie by their support or the lack thereof. Studios now bring their filmmakers and stars to the bigger comic book conventions to pay homage to the fans they know they must ultimately win over. There are currently so many dozens of key fan sites on the Internet, with millions of people trolling them all day and late night. It is a bonded community where word spreads like lightning. The Internet is not only important to market a genre film domestically and internationally today, it is essential.

I will come back to websites, social media, and online generally later, but I want first to continue my focus on timing; the matrix of elements associated with timing can profoundly impact a marketing campaign. When it may be best to launch a film is driven by both “internal” factors related to the inherent/specific elements of the property, as well as “external” events that impact consumers’ consumption patterns but are otherwise unrelated to the film at hand.

Internal Factors

The most important element of timing is that external events are as influential, and arguably much more influential, than direct elements (“internal”) driven by the film/property. By internal, I mean particular relevance of the property that dictates specific optimal release timing. Perhaps the best example of this is films with holiday themes. A Christmas-themed movie, such as Christmas with the Kranks, Four Christmases, Polar Express, or even The Chronicles of Narnia series, should be released during the year-end holiday period to optimize interest. Similarly, movies with beach themes (e.g., surfing-related) are clearly a more natural fit in the summer. Occasionally, there are movies with literal direct tie-ins to dates, such as Home for the Holidays (starring Holly Hunter), which involves family coming home over Thanksgiving; Independence Day (about science fiction and not about the Fourth of July), which had a clear marketing hook on July 4th; Halloween (and other thrillers) around Halloween, New Year’s Eve (released in the holiday season 2011), and sports movies that revolve around the sport currently “in season” (such as The Rookie or The Natural during baseball season, or Remember the Titans, Leatherheads, or Friday Night Lights during football season). When listing just a few of these tie-in categories, there becomes a larger overlap with theme and timing than one would likely identify without reflection.

Because people are looking for films with “the Christmas spirit” in December, about love on Valentine’s Day, about the beach during the summer, and about baseball during baseball season, it is obvious to find films with these themes releasing in these time frames. Simply, the themes of these types of films are top of mind; importantly for marketing, they also create an alternative reference (versus key word genre categories such as action, romance, thriller, drama, chick flick, etc.) that subliminally, or probably overtly, drives interest. (Note: It will be interesting to see if such themed movies continue to be as prevalent with the international marketplace becoming dominant; most sports and holiday themes tend to be local, making it challenging to market properties into an increasingly culturally diverse and dispersed global marketplace. Because the U.S. market is so large in itself, these films will not doubt continue to be made, but I would suspect there may be increasing scrutiny at budget levels as studios segment their portfolios.)

By external events, I mean outside factors wholly unrelated to the film that have a material impact on people paying money to go to the theater. The four principal elements are: (1) events of national or international importance; (2) holidays; (3) competition; and (4) economic events.

Events of national importance, while obviously a broad category, generally means major events known about significantly in advance, such as political elections or major sporting events. Not only do these events draw attention away, making it harder to compete for viewing, but these events drive up the price of media. On the sports side, distributors take into account dates for the Olympics, the World Cup, and major sports playoffs and championships (whether Formula One events in Europe or the Super Bowl in the United States). For politics, the concerns may be more limited, but periodic major events such as presidential elections will dictate timing. Again, this is driven as much by having to compete with an external event perceived to be monopolizing (or at least drawing) target consumers’ attention as with the corollary impact of the cost of media. Having to buy media time during a presidential election when key outlets are able to sell spots at a premium (and when inventory may even, in some cases, be sold out) simply drives up budgets, with no fringe benefits.

The second external category, holidays, is important not because holidays can get in the way (as in the case of an election or sporting event), but because they create free time. The entertainment business is at the heart of the leisure industry, and the more people have free time, the more likely they are to consume an entertainment product. Accordingly, the biggest release dates of the year are around U.S. Memorial Day weekend (commencement of summer break), the Fourth of July, Thanksgiving, and Christmas. Movies are a social experience, and film marketing tries to drive a truck through the gates held open by the dual forces of getting together and compulsory free time. Box office is largely driven by weekends, and in terms of marketing opportunities, key holidays are nothing short of weekends on steroids.

For kids, the summer season is the most critical release period of the year; having extended periods of free time while being out of school drives up weekday box office numbers, validating the holiday/vacation relationship (see also Chapter 4).

The third external category is competition, perhaps the most overlooked and yet, at the same time, arguably the most influential factor in terms of attracting an audience. Competition can be subdivided into a couple of categories: direct competition among films for market share, and competition among studios and rivals (which can, at times, add an emotional and even irrational component). Regarding direct competition, distributors will always be looking for the “cleanest” window. Would you want your next film to be opening against the next Avator, Avengers, or Star Wars? Certain event films can suck so much of the box office out of the market that it becomes questionable whether other films can perform simultaneously. Studios perform sophisticated analysis on the market size, and what portion of a demographic they want to attract, but whether the market can expand to handle certain capacity is always a tricky calculation.

Studios therefore jockey for release dates and try to put a stake in the ground early to ward off would-be competitors. Sony and Marvel, for example, in early 2009 announced it would release Spider-Man 4 on May 6, 2011, securing the pole position in the summer box office race, a position Marvel covets and similarly secured in 2010 with the slotting (more than a year in advance) of Iron Man 2 on May 7, 2010.3 Continuing this trend, in October 2010, Walt Disney Pictures (following its acquisition of Marvel and obtaining distribution rights to future Iron Man sequels) announced its release date of May 2, 2013 for Iron Man 3. With summer weeks and holiday weekends at a premium, it has become commonplace to map out release date schedules years in advance (see Chapter 4 for a further discussion of release dates).

One of the most time-consuming and important parts of the art of theatrical distribution is trying to track the matrix of competitive titles, and both schedule and protect release dates. As a result, dates are either universally known and touted (to ward off others) or guarded with strict secrecy to keep competitors guessing. As dates get close, the cat is, of course, let out of the bag and lots of last-minute jockeying takes place. The most intense poker game is played in the summer (the busiest time of year), since a new tentpole film is releasing virtually every week.

In terms of efficiency, it would be simpler and better for all involved to work through a trade association and schedule dates, eliminating the secrecy and politics, and allocate slots in a fashion that would optimize the pie. This practice, however, is deemed collusive and violates antitrust and international competition laws. I was once involved with a case in Europe alleging collusion among studios in setting release dates, a case that was ultimately dismissed but still sent a chill through the spines of the parties involved.

I would argue that while collusion is possible, and would create more efficient economics, the fact remains that the film business is cutthroat: the desire to best a rival dwarfs the forces of collusion and ensures true and vibrant competition. And remember, this can be a business driven by irrational competition—people’s jobs and star can rise and fall by rankings and even perception. There is more than an ego element to where a studio falls in terms of box office rank (e.g., top distributor of the year). With so much riding on a film’s performance and its opening, paranoia comes into play. No matter what a film’s marketing budget is, there is always fear that the budget of a competitor’s title is higher. Add to this equation the fact that when the marketing budget and decisions are being mapped out the film may not be finished (or the people doing the planning may not have even had a chance to see it), and that no matter what the questions may be about your picture you are going purely on hearsay regarding the competition. This is not like marketing one brand of soap against another. This can be a lastminute chess game involving the blind leading the blind. Driven by emotion, imperfect information, extremely high stakes, and fierce competition, passions can run high.

Moreover, given this hyper-competitive environment, a studio may try to maximize results by counter-programming (a strategy that may draft off of increased in-theater foot traffic, target a different demographic than is drawn to a new blockbuster picture, or simply address the too much product, too few weekends challenge). An extreme instance of counter-programming is to spend with the intent of crushing a competitor’s film. In the context of battling brands, it can be as much of a success to undermine a key competitor’s film as to launch one yourself. Of course, no one will admit to this, but it can be gleaned in the marketplace when there are obvious rivals or niches to protect.

I will label the final key external category as economic events. While this can sound a bit amorphous, marketing at its most base level is trying to encourage people to spend money. Just like periods of holiday that create free time, there are periods that stimulate “free money.” Paydays and bonus periods can become catalysts for planning product releases (and conversely, tax day, April 15, is probably a time to avoid). In certain countries, there are traditional bonus periods, and in some countries bonuses are either legally or culturally built into salary structures, such as a “13th month” of pay. This factor is much less influential in terms of planning a theatrical release, because the relative cost of a movie ticket is low. If the price of admission is not a barrier to entry on a weekend, then it is hard to argue that a release should be planned around a bonus period. This timing tends to be much more pivotal at retail (e.g., for DVD release), and is something likely tracked by the Walmarts of the world; a study of product releases to paydays (1st and 15th of the month) would probably yield a closely mapped curve. Perhaps this is overanalyzing, for the likelihood is that in most cases, this factor happens to dovetail with other elements, such as year-end bonuses overlapping holiday periods.

It used to be the pattern that a film would open in the United States and then be released subsequently in international territories. This had multiple advantages, including: (1) saving money on prints by being able to reuse prints and send them to a different territory when one territory wound down (“bicycling of prints,” which is, of course, limited to common-language territories); (2) allowing talent to travel to staggered premieres; (3) enabling the heat from the U.S. release (e.g., box office, reviews) to spread to the rest of the world; (4) allowing the marketing department to learn from the U.S. release; and (5) simply allowing time to complete international versions (e.g., subtitles, dubs). As discussed in greater detail in other chapters (see Chapters 2 and 4), however, piracy and other pressures have led to studios now favoring day-and-date releases (especially in the context of event films, even if this means increased print costs), which simply means near-simultaneous release of the picture in all territories. Moreover, with the size of the international markets now eclipsing any domestic market (whether viewed from a perspective of the U.S., or any other country), if a release is not day-and-date, it is no longer unusual to release overseas first, as was the case with The Avengers and Battleship in 2012 (see the discussion in Chapters 1 and 4).

Given the ever-increasing importance of international markets results, reducing the impact of piracy has grown in importance; moreover, the combined forces of a global economy and easy Web access force distributors to assess the risk of a picture illegally showing up in a territory before its scheduled opening—and this risk is not only very real, but its impact is exacerbated as the size of the international markets’ growth as a percentage of overall box office/revenue (see Figure 1.7 and Table 4.1 in Chapters 1 and 4). Day-and-date releases have accordingly come to be perceived as the best prevention against piracy; the pattern also yields the biggest worldwide box office number the quickest. In terms of economics, the calculation is whether the accelerated international release will bring in more money (than would otherwise be lost to piracy) than the incremental costs associated with simultaneous release (e.g., extra prints, overtime to rush international versions). (Note: This is an even more difficult equation in practice because inevitably a simultaneous release means that in some territories, given cultural patterns, seasonality, outside events, etc., the timing will not be optimal.) The elimination of the chance to learn from and tinker with earlier marketing strategies is an intangible that will not lead the decision, especially since global marketing is usually driven off the U.S. campaign.

Third-Party Help: Talent and Promotional Partners’ Role in Creating Demand

Nothing sells a property like a star, and the magnitude of the star and their willingness to promote the film can be a significant factor in the overall strategy. This is a double-edged sword, however, for talent can be unpredictable—both in terms of dedication to the project and timing—and very expensive (think entourages, first-class travel, and accommodations). Much needs to be put in motion in advance of the release, and the mechanics of production are such that most big stars are well into other projects by the time the prior film has completed post production and entered its marketing and release phase. Accordingly, while personal commitment, emotion, relationships, and ego are gossiped about, the fact is that time management can be the paramount concern. Even if a star is committed to promoting a film and willing to travel for publicity, they could be tied up with another project (worse if on location) and simply have limited availability.

The advantage to using talent/stars to promote a film is the enormous amount of free publicity that can be generated. The talk show circuit, ranging from morning shows (e.g., The Today Show) to afternoon talk shows (e.g., Ellen, Oprah), to late-night programs (e.g., The Tonight Show), generates significant exposure and tends to foster other appearances and press opportunities. The downside to using stars (beyond costs) is lack of control.

Unlike a trailer or advertisement, a star as a spokesperson may or may not put on the appropriate spin. Given, however, that the preeminent concern at this phase is awareness, the risk is usually worth taking. Stars are paid enormous sums, and that premium is largely for awareness: people want to see them, know about them, go to their films. They are a presumed built-in draw, the “sure-fire” way to entice the consumer to pay money to go see the product (though statistically, this has been proven a fallacy). Famously divorced from Nicole Kidman, engaged to Katie Holmes, and often front-page news for his promotion of Scientology, Tom Cruise had achieved as many headlines for jumping on a couch during The Oprah Winfrey Show and behaving erratically as anything else during the promotional window for Mission: Impossible III—the public perception was starting to turn from golden boy to eccentric. Shortly following Mission: Impossible III’s failure to meet certain expectations, Paramount ended its long-term deal with Cruise’s production company, with Sumner Redstone (chairman of Paramount’s parent, Viacom) publicly mentioning Cruise’s personal behavior among the reasons for its decision (sending some shockwaves through the industry). At this point, many were questioning whether the star’s appearance would help the picture, or whether the risk of negative publicity may hurt it.

Stripping away the artistic element, and whatever life and magic they breathe into the end product, at its most base level stars are a vehicle for instantly branding a film. An unknown product, for which hundreds of people have spent months of their lives, becomes a such-and-such film. Given this inherent branding, whether fair or not, it is economically wasteful not to use that branding in turn to create branding and awareness by association for the film. If a movie has lots of talent involved, such as a famous director, then there are simply multiple hooks to exploit.

Promotional partners can, on occasion, influence timing and positioning. A cereal company or fast food company may be willing to create product tie-ins, and even pay for advertising. An advertisement by a cereal company, Burger King, or McDonald’s can create huge demographic-specific awareness.

It is important here to distinguish between merchandising and promotional partners. A merchandising deal (see Chapter 8) is generally a licensing arrangement where a third-party company pays a fee to the property owner for the right to create certain goods featuring elements of the property. The end product is therefore a Batman action figure, a Spider-Man costume, or a Toy Story backpack. In contrast, a promotional partner already has its own product, usually a very well-known branded product. What it is offering is a chance to tie-in its brand in a fun way, utilizing elements of the film brand. Accordingly, a kids’ meal at a restaurant may be themed for the week using characters from the movie, or a character from the movie may appear on a box of a well-known cereal. These are instances of cross-promoting brands as opposed to creating a unique new product SKU designed solely around the elements from the film.

If a distributor is fortunate enough to have a property that lends itself to this type of tie-in (these opportunities are limited to big films), then lead time must be built in and limits on content may be imposed. The promotional partner, no matter how much it may like a film idea or property, is still self-interested: it is simply trying to attract more consumers to its product by associating itself with another property (brand) on the assumption that the tie-in will lead to a lift in sales. It is not willing to risk its own brand on a tie-in that could undermine its brand. Accordingly, violence and other content tied to age ratings is critically important. A tie-in partner such as a toy company, for example, targeting a kids demographic is likely going to be extremely concerned about content not being too violent or sexually explicit.

Assuming the content hurdle is cleared, then the next key issue is timing. Product development timelines are years out, and it is not uncommon for promotional partners to be locked in up to a couple of years in advance of a release, and for the partners to demand locked release dates. Given this time frame, promotional partners tend to align with known film brands. This creates a mutual comfort factor—both the product brand and film brand know what they are dealing with—and is also a practical necessity. At the time the partner tie-in needs to be locked, the film may not have even been started. How can a major corporation with a household brand commit to a tie-in and spending up to millions of dollars on blind faith? Only by associating with a known brand, and feeling as if there is only an upside.

One of the best-known partnerships was a deal struck between Disney and McDonald’s. Both companies agreed to a 10-year exclusive arrangement. It was a brilliant move by Disney, for in one stroke they gained exposure at the largest fast food retailer in the country and also excluded competition. At the time for McDonald’s, Disney was considered the only “studio brand,” and as a consistent family-friendly brand, it meant a high-quality, safe association.

Whenever there is a group of sequels coming out in the same period, as now routinely happens in the summer, key brands are courted by rival studios, often leading to intense competition: there are only so many large packaged food companies, soft drink companies, fast food outlets, candy companies, etc., and everyone wants to affiliate with the market leader. Moreover, not only do they want the market leader to associate with their film, but they want that market leader to help brand the film by spending their own advertising money and creating unique in-store displays. A successful campaign spreads the message over the airwaves and at retail, creating millions of impressions and potentially exponentially increasing the media weight behind a campaign. Table 9.1 lists a few high-profile films, illustrating how major brands can garner tens of millions of dollars worth of promotional partners, and in extreme cases upwards of $100 million in value.4

Table 9.1 Promotional Partners

Film |

Promotional Partners |

Details and/or $ |

Spider-Man 3 |

Burger King, General Mills, Kraft, Comcast, 7-Eleven, Walmart, Target, Toys “R” Us |

• Approximately $100 million in media, mainly on commercials • General Mills promo involved 20 brands in 12 categories, putting the film on approximately 100 million packages • Kraft—10 product brands |

The Bourne Ultimatum |

Volkswagen, MasterCard, Symantec, American Airlines, banks (ABN-AMRO, HSBC, Barclays) |

• $40 million value across partners; Volkswagen alone committed to approximately $25 million (Touareg2 featured in film action sequences) • Symantec’s Norton Antivirus “Protect Your Identity with Norton” tie-in campaign |

The Avengers |

Acura, Dr. Pepper, Visa, Wyndham Hotels, Harley-Davidson, Farmer’s Insurance, Hershey’s Oracle, Red Barron Pizza |

• Marvel/Disney secured estimated $100 million in marketing support • Red Barron spent $5 million on Avengers-themed packaging on 13 million pizzas and in-store marketing as multiple supermarkets/grocers |

Animated and family-oriented movies often lend themselves to a broad swath of promotional partners. In 2012, DreamWorks Animation’s Madagascar 3: Europe’s Most Wanted had more than 10 partners ranging across food, cards, games, hardware, and apparel. Table 9.2 is a partial sampling of the types of products and categories that were involved.5

Table 9.2 Madagascar 3—Select Promotional Partners

Brand |

Tie-In Support | |

Snacks |

General Mills |

Film-themed packaging featuring snacks in the shape of the penguin characters |

Fast Food |

McDonald’s |

Custom TV commercial, in-restaurant integration, and tie-in with six circusthemed toys in global Happy Meal program |

Candy |

Airheads |

Dedicated TV commercial and in-store displays |

Party Goods and Cards |

Hallmark |

Various retailers and Hallmark Gold Crown stores |

Credit Cards |

Citibank |

Private card member screenings in New York and Los Angeles |

Social Games |

Zynga |

Draw Something game tie-in with four themed words players can draw; also video trailers |

Toys |

Toys “R” Us |

Dedicated in-store boutiques |

Fruit |

Dole |

“Go Bananas Every Day” campaign with 100 million specially branded stickers, tied to QR code mobile game; also linked to promotion in Walmart’s produce department |

Cosmetics and Beauty |

L’Oreal |

Four Madagascar 3-inspired kids’ shampoos and conditioners |

Hardware |

Lowe’s |

In-store POS, themed clinics, and movie-themed racecar driven by Jimmie Johnson at Dover race weekend |

Product Placements—Finance-Driven, Not Marketing-Driven

Product placements are similar to promotional partner tie-ins, but are generally distinguishable in that the third-party promotional partner will also advertise outside of the film/property; hence, such third-party will leverage its brand in retail together with the tie-in film. In contrast, a pure product placement will only involve integrating a consumer brand into a film, television, or online property, where there is an indirect association. Examples of a product placement are the judges on American Idol drinking a Coke (with the Coca-Cola bottle and logo prominent), or the financing of certain online originals having a character wear a particular fashion accessory (e.g., brand of shoes). In both of these cases, the viewer is drawn to the product, with the character (or in the case of the reality program or contest, the judge or host) using the product as the marketing hook. There is no direct tie-in between the brands. The lines here can be quite fine, as a car used in a film (e.g., a special sports car in a James Bond or Bourne film) is a kind of product placement; however, because in these types of cases there may also be off-film marketing (“see … in the James Bond film …”), the deal may be better characterized as a promotional partner tie-in.

Another way to distinguish between these types of arrangements is that promotional partner deals are generally designed to add marketing weight and promotion to a show or movie. In contrast, product placements do little to promote the show, but create a separate revenue stream (basically in-show advertising) that can be viewed as defraying production costs (i.e., a method of financing) or a revenue stream helping to recoup production costs. It is for this latter reason that several online original programs, unable to secure enough revenue from new advertising markets, have utilized product placement opportunities to help finance production (see Chapter 3). The challenge with product placements is that creators often bristle that they undermine the integrity of the show, and the brands that are usually prominently featured (to justify the fees paid) may date the shows in the long tail.

One way to defeat these problems is to create a product placement that has functional relevancy. This, however, is difficult to execute creatively, for the product needs to be built into the show and integrated at an early stage. A few years ago, I saw an example in the online context that may be an ideal model for utilizing product placements. The online social network Gaia Online, which allows people to build environments and socialize via avatars in a virtual world, innovated a clever way to integrate product placements that went beyond simply seeing the visual. As has fast become a trend, users can buy virtual goods to dress up their characters, and in this instance, could buy Nike shoes. What is different is that when the character wears those shoes they go faster, creating a relevancy and functionality that creates more value for the brand and does not detract from or compromise the underlying content. In this example, the Internet has taken product placement to another level. To a degree functional relevancy of products underlies the economic models in social games where the business goal is to seduce players to ante up and pay for additional elements helping them/their characters succeed and progress to a new level; it is accordingly not surprising to see companies searching for tie-ins where products offered contain brand appeal (and benefits) over generic accessories.

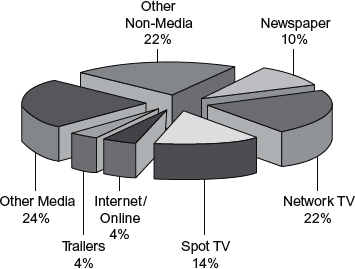

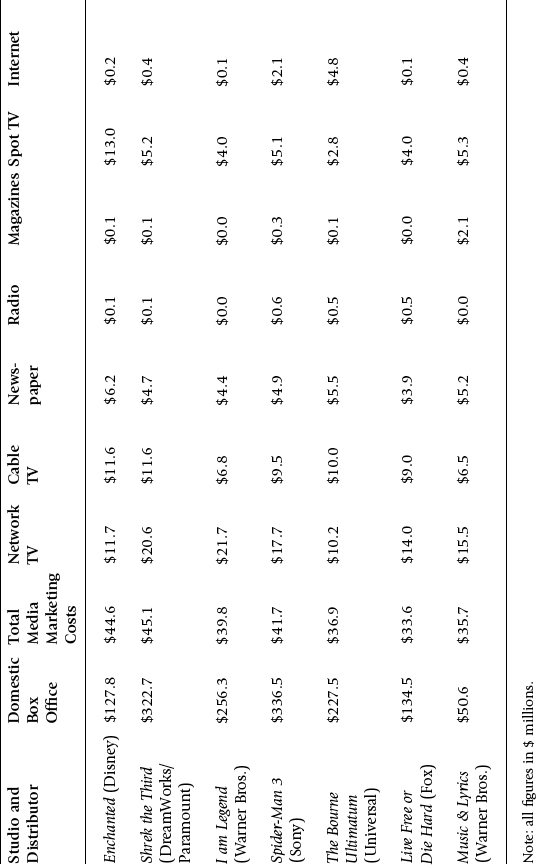

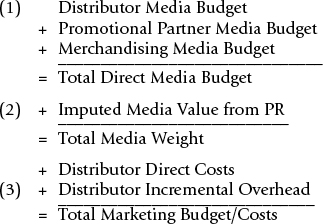

The marketing budget is the largest cost outside of physical production impacting the P&L of a film. Given the increasingly competitive nature of the marketplace, and the compressed periods of theatrical release (see Chapter 4), the costs of marketing have spiraled to almost unimaginable highs. As already referenced, the average domestic cost for an MPAA member studio to market a film in 2007 was $35.9 million, a sum that has continued to hover at roughly this level (see Figure 9.1).6

By far, media is the largest cost category. Media costs and strategy involve mapping placement to demographic targets and achieving a certain reach and frequency. This is often expressed in terms of percentage of target reached, such as 70 percent, and how many times that grouping is hit with impressions (such as one, two, or three times). Media buys are then made on the basis of impressions. The end goal is to achieve a certain awareness level, which then hopefully translates into consumption.

Media buys are aggregated in four principal areas: television and radio, print, outdoor, and online. These categories are exactly what they sound like. TV and radio are simply commercial spots of varying lengths. Outdoor ranges from billboards to sides of buildings to buses and phone kiosks. Newspaper/print involves advertisements that can differ by size, prominence, color, etc., and like TV can be executed locally, nationally, and to finely tuned demographics (e.g., women’s magazines). Online is a catch-all encompassing everything digital: Web, mobile, social. There is no magic formula, and different marketing gurus will allocate different weights depending on their experience and, to some degree, gut feeling. Some believe that with increasing media diversity and competition that the middle is disappearing; namely, either spend modestly and targeted, or spend big enough to rise above the clutter.

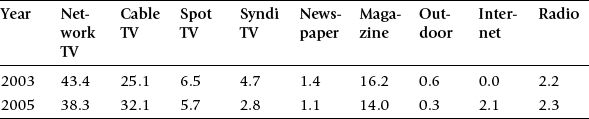

TV advertising alone can often account for more than half of the total media marketing costs. The allocation of costs is a picture-by-picture decision, but historically the largest costs have been first TV advertising, next newspaper advertising, and then the balance of the pie divided among Internet, outdoor (e.g., billboards, buses), and radio advertising. The biggest shifts in recent years have been the decline in newspaper advertising, and the increase in “digital” spending (which is now not only Web/online, but also encompasses social media and mobile advertising). These are difficult costs to track in the aggregate, but Figure 9.1 gives a snapshot as to the prominence of TV spending in 2007 and the then relatively small amounts of advertising committed online. It is also useful to look at the breakdown on a per-film basis. Table 9.3 provides select examples across key titles from a variety of studios, as referenced in the Hollywood Reporter.

Figure 9.1 MPAA Theatrical Marketing Statistics: MPAA Member Company Average Distribution of U.S. Advertising Costs 2007

Note: Other media includes cable/other TV.

Because media costs are front-loaded to open a film, pursuant to the compressed theatrical box office curve, if a film underperforms it is too late to adjust. Accordingly, for films that do not achieve box office numbers greater than $100 million, the percentage of marketing costs relative to box office can be a frightening number. This was the case with Music & Lyrics, starring Hugh Grant, where the marketing costs were more than 70 percent of the total box office (and remember, rentals are roughly half the box office, meaning that the marketing costs significantly exceeded the revenues taken in by the distributor at this stage). In the most extreme case, the numbers can exceed the box office, which directly translates into media feeding frenzies about the film bombing, and in the worst of scenarios finding a place among the all-time clunkers.

Table 9.3 Marketing Cost Breakdowns for Selected Films

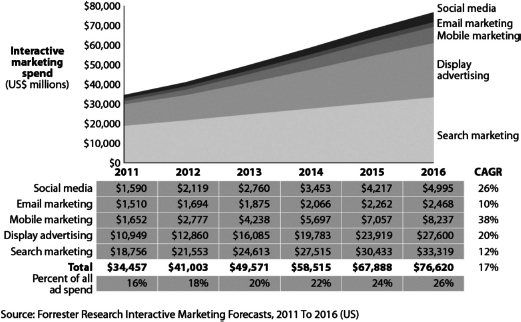

The power of the Web to target messages to specific demographics is a marketer’s dream, and the budgets for online advertising continue to grow. The 4.4 percent that the MPA estimated was spend for online/digital advertising grew to more than 10 percent by 2010, essentially flipping the importance of newspaper advertising, which fell from 10 percent to 4 percent.8 Although television continues to dominate marketing expenditures for film releases, with Variety estimating (early 2010) that TV accounted for 60–70 percent of a studio’s promotional budget,9 it is likely that online/digital marketing budgets will continue to grow and cannibalize part of the TV spends for the next several years. This shift is not specific to the movies, but essentially tracks the broader marketplace. Forbes, quoting a forecast by Forrester Research, predicted that online advertising would, in fact, overtake TV by 2016 (see Figure 9.2).

While increased advertising online may seem an obvious trend in terms of promotional campaigns for films, I have heard some argue to the contrary, noting that a trailer that is released virally can be accessed from thousands of points and need not require advertising. As a studio, if your best message is the visual, and online distribution of a trailer is free, then why additionally pay for advertisements? This theory is buttressed by the nature of experience goods. As earlier discussed, advertising helps the consumer feel as if they have experienced the film; the consumer then creates signals that may lead to cascade behaviour, which may be further accelerated by viral sharing among users frequenting social networking sites. Of course, this information flow and result can also turn negative, which is a complicated way of saying that whether a trailer is compelling is now even more important in the online world. I would argue, however, that this line of reasoning is purely theoretical, and that to create viral sharing of a trailer it is necessary to invest in promoting it. More sums will be allocated to online outlets, and especially social network sites, where clever advertising can be a catalyst for sharing. The promise of direct marketing, inherent efficiencies of reaching an exact demographic, the ability to report precise 1:1 metrics, and the inevitable maturation of the space mean that allocations will continue growing. Moreover, they are likely to grow both in sub-markets, such as social medial and mobile, as well across the entire wireless and online/digital spectrum.

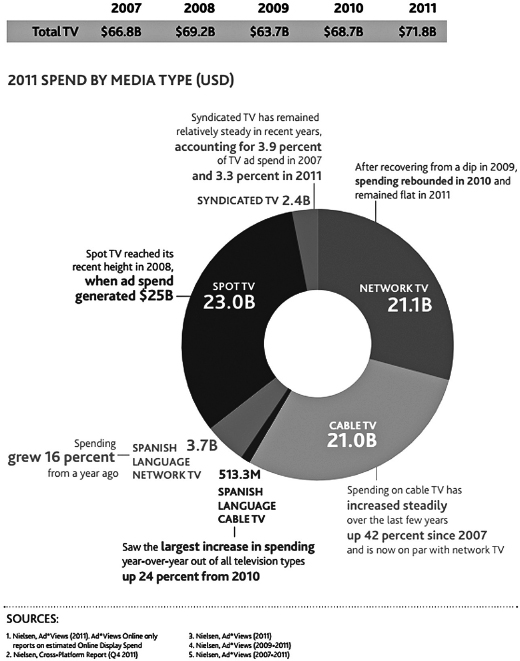

Despite my belief in the growth of online (which is clearly happening), a macro shift in allocation from TV to online has not yet happened—largely because TV advertising has proven remarkably robust. In fact, over the last five years, total ad spending on television has increased, with Nielsen reporting that total ad spending in 2011 increased 4.5 percent to a total of $72 billion, and that since 2007 cable advertising spending has increased a whopping 42 percent, with cable and network spending now virtually equal.10 Figure 9.3 provides evidence of the upward trend in overall spending on television, as well as how virtually all segments (e.g., cable, network, syndication) have either held relatively steady or shown a material increase.

Figure 9.2 Projected Online Advertising Expenditure

Reproduced by permission of Forrester Research.

What these trends evidence is that certain traditional promotional areas, such as newspapers, will continue to wane, and that online, television, and outdoor advertising (e.g., billboards) will continue to be a staple for advertising releases. There is already a push to leverage social media in a more proactive way (see discussion below), and it is inevitable that the allocation of marketing budgets will continue to shift as metrics continue to prove the efficiencies that well-orchestrated and well-tuned online advertising can deliver.

Correlation of Marketing Spend to Success

While William Goldman is correct that “nobody knows anything,” and most statistical correlations of top box office stars to movie performance evidence that stars, in fact, do not guarantee a project’s success, at least one popular benchmark seems true: bigger-budget movies tend to yield the best return on investment. Despite the seemingly bigger risks (if we assume higher marketing costs go somewhat hand in hand with higher budgets), the most costly films are, on average, the most profitable, with an SNL Kagan study finding that of all films with wide releases (i.e., more than 1,000 locations) between 2003 and 2007, “the two priciest segments surveyed showed the best profitability … 80 films costing more than $100 million to produce showed average profitability of $282.3 million.”11

Figure 9.3 Television Advertising Expenditure

Source: Nielsen, State of the Media (Spring 2012), Advertising & Audiences, Part 3: By Media Type. Reproduced by permission of Nielsen.

The goal of the trailer is obviously to entice interest in viewership, and hopefully to create awareness through both direct viewing and word of mouth. The problem with the creative is that the trailers often have to be cut before the film is completed, and this is almost always the case with teaser trailers (which further means there are instances where scenes in the trailer may not make it into the final cut of the movie). This problem is exacerbated by effects-laden films, where shots may be filmed in front of blue or green screens and effects shots then created and integrated into the frame. The job of cutting/creating a trailer is simply to do the best with what you have available.

For the distribution budget, the cost is in creating the negative and then printing the physical trailers for distribution. Although the trailer itself is short, the number of copies can be in the several thousands, as the goal is to achieve the broadest possible market coverage. Trailer costs can therefore be significant when adding up the several line-item categories:

■ creative and mastering

■ focus group testing

■ physical prints

■ cans for shipment

■ freight and transport.

There are accordingly economic decisions regarding trailering, as the distributor needs to judge how many versions of a trailer to make (if the film warrants targeting to different demographics, such as a love angle geared toward women and action sequences skewing toward men) and how many copies to print (although, as discussed in Chapter 4, the growth of D-cinema is eliminating the costs of physical prints, which will in tandem ultimately eliminate the costs of distributing trailers and change this calculus). Complicating these decisions is the fact that there is no guarantee as to how many of those copies will actually be shown—it is up to the discretion of the local theater what trailers will be played. In some cases, a certain number of limited trailers will be attached to the front of the film print, thereby somewhat guaranteeing placement. These attached trailers are precious real estate, and the decisions of what is trailered with what, and what is attached, will even go up to the head of the studio.

The placement of trailers, and direct linking where possible, is critical because everyone wants to have their trailer attached to the film(s) with the best demographic overlay to the target market for the future film. One can imagine the politics of this choice, with different investments in different films, lobbying by directors and producers, key relationships with clout … Everyone wants to be on the front of the next blockbuster, and competition will be fierce to piggyback on event films.

The studios will receive reports of trailer coverage after the weekend, which is the ultimate gauge of whether the right range of copies was produced and shipped. Of course, all of the previous discussion addresses physical trailering, but as earlier noted, trailers will also be posted online and can potentially achieve greater reach and frequency via the Web and viral sharing. Trailers, in summary, receive so much attention because, by their nature (including their ability to solve the experience-good problem), these visual teasers continue to be among the most efficient of marketing tools both online and offline. Interestingly, they are an example of a practice as old as films that has found a way not only to survive, but even grow in importance in the Internet age.

Teaser and Launch Trailers

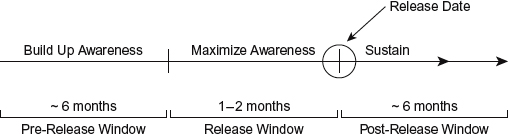

Tentpole-level films typically have a teaser trailer six months or so in advance of release, and then a launch trailer a couple of months in advance of the release date.

Because of the limited material available for teasers, they tend, by their nature, to be short at around a minute in length. Taking into account lead times, for a summer movie teasers will often release in the fourth quarter of the prior year, taking advantage of the holiday box office season and the large audiences that will be attending theaters. Similarly, teasers for holiday films will often accompany summer releases. This is a relatively efficient way for a distributor to start spreading the word about an upcoming blockbuster.

A launch trailer, by comparison, is a very different animal. The launch trailer, released much closer to the theatrical release, will usually be much longer (e.g., two-minute range as opposed to one minute), and rather than “teasing” will give the audience a better sense of the story/what to expect in the movie. Many people often complain that “the best scene was in the trailer or commercial,” but it is hard for a marketing executive not to cull from their best assets to entice people into the theater.

Posters, or in film parlance “one-sheets,” have been around as long as movies, and to some are even considered a distinct form of art. The poster is simply a single static image used for the same purposes as the trailer. Knowing that the poster may have more visibility than any other piece of artwork in promoting the film, it needs to convey a succinct and compelling message. This will be the piece most likely picked up by the press for initial coverage, and the enduring image at the box office. Additionally, one-sheets (unless replaced by digital video box art) become the artwork for thumbnails, indexing the image in search engines, websites and virtually all online/digital outlets.

The economics of the poster is similar to trailers, just less expensive (usually). Posters are less costly to manufacture and distribute (with the cost of thumbnails as regards online marketing virtually zero), but interestingly the creative can be much higher. Because movie posters are often deemed works of art, and the commissioning of artwork, simply put, can be as expensive or inexpensive as the budget can bear, this is an area of both real and niche celebrities. The subjective nature of posters also lends itself to focus group testing, as messages can range from direct to mysterious. Additionally, as sometimes happens with high-profile films, posters may mimic trailers, such as when a unique teaser poster accompanies the teaser trailer, and a release poster dovetails with the launch trailer messaging. It is all about what will draw in the audience, and the answer may not be the most clever or creative. This is an area that can be lots of fun, and truly lets creative marketers have a significant impact on the film.

One final item to mention about posters is that they can be sold, thereby creating an ancillary revenue stream not available with trailers. In general, however, these sales are incremental to other merchandise, and it would be rare to factor this revenue into the equation. In fact, the marketing department will have the task of delivering posters within a budget range, and will likely never know anything about the revenues, if any, earned from later sales.

In-Theater

A related element to posters is in-theater advertising. At the simplest level, in-lobby posters provide direct marketing to those making their decision of what to see once at the theater. This element has grown in importance with the expansion of multiplexes, and is critical in enticing would-be customers making an impulse decision once already at the theater. In-theater advertising may also involve more elaborate marketing, such as standees, additional signage, branded concession items (e.g., cups), and even billboard-type advertising outside.

Commercials (Creating) and Creative Execution

Creating advertisements for a property is similar to the process of cutting trailers, in that for bigger films there may be multiple versions generated. Commercials can be tailored to targeted demographics (e.g., playing up action scenes to a hardcore male audience) and then the media bought accordingly. Hence, there can be a very significant range, from very targeted ads to workhorse broad demographic spots.

In addition to the multiple versions, each version may be edited for different lengths. Commercials can range from a tag of a few seconds, up to a minute, with most spots cut to 15 or 30 seconds. Again, what will work best is a gut creative call based on overall budget (although, budgets permitting, distributors will test the spots on focus groups to optimize the outcome).

Finally, there is an economic call regarding the extent to which the process is managed in-house versus outsourced. Given the volume of product and challenges it is common for studios to work both with advertising agencies as well as trailer specialists. Only in Hollywood, though, could a trailer specialist become a main character, such as Cameron Diaz’s role in the 2006 Christmas release The Holiday.

Creative Execution

Although it may sound like a truism, the quality of the creative is a critical factor in the success of a commercial, as well as all the other marketing elements discussed. The same problems that lead to challenges with creative goods underlie the creation of marketing materials, though smaller in scale and tempered by the fact that the creative is derivative of another property (i.e., the film). Commercials win awards too, and whether commercials or other marketing materials achieve their goal of creating awareness and stimulating consumer interest may be subject to the intangible of creative execution.

Press and PR can form a major part of the overall marketing campaign, and few realize both how complicated and time-consuming orchestrating all the elements of PR can be. Areas that PR has to manage include: (1) press kits; (2) press junkets (both long and short lead); (3) reviews; (4) talent interviews and management; (5) tie-ins/placements on other media such as TV shows; and (6) screenings (in coordination with distribution).

Press kits historically included fact sheets, press releases, slides, and some glossy photos. Today, if still used, they can still include these elements, and are supplemented with online elements; however, online press kits (i.e., electronic press kits; EPKs) have been the norm for a few years, and I would suspect that by another edition of this book physical press kits will we seen as a quaint anecdote from the past. Regardless of form, press kits are vital in terms of key messaging, and making available images to be used in print, television, and online coverage. A good press kit is engaging and informative, and also has direct messaging—the film, if not already a brand, will hopefully become one, and staying true to a brand requires concise and bounded messaging. Everyone wants to write the review and article, and the press kit gives the journalist hold of the driving wheel and a guided map. How and where they then drive and chronicle the journey is out of PR’s control, but a good press kit guides the less adventurous driver along the scripted route.

Handouts are limited in a business of glitz and images, and studios therefore choreograph press junkets. These interactive sessions will allow invited journalists to talk with key talent, learn about unique production elements, and taste a bit of the film. The cost of junkets can be high, involving renting and decorating venues, catering parties, creating custom reels, flying in and putting up talent/celebrities, and creating takeaways/goodies. Against this budget, the marketing department needs to place a value on the level of awareness and hype that the journalists and bloggers will ultimately create. What is the value of a good piece on Entertainment Tonight or a story in The Huffington Post versus the cost of a 30-second commercial? Press is, at some level, just another angle and tactic to create interest that will spike awareness and attract consumers.

Beyond the tried-and-true press kits and junkets/press conferences, good PR will take the film into another media space and create tie-ins. Convincing Saturday Night Live to have the star of the film host is a good example of this strategy. (Do you think it is a coincidence that Zach Galifianakis happens to host just before his next Hangover movie is opening?). Similarly, a star of an upcoming film may make a special guest appearance on a scripted TV show, creating buzz and interest; not so surprisingly, vertical integration between network groups and studios allow this. Everyone loves seeing a character out of context in a cameo appearance, and on occasion, such as when a Desperate Housewife shows up in a locker room for a sports promo, the media attention can reach a frenzy. Can there be better publicity than being written into an episode of The Simpsons, even if the character or person may be the subject of a witty slander?

Finally, PR is the group that manages talent interviews. Every outlet wants time with the director, producer, or star, and PR orchestrates the maze of interviews. It is PR that has to manage who has an exclusive, whether there is a press embargo (granting information in advance for stories under the pledge that a story will not run before a specified date), and when and where talent will be available. Although talent will have agents and managers, it is the studio machine that will set in motion the blitz of appearances on talk shows. Basically, PR often functions as the gatekeeper to talent, and manages access to talent in a way that at once is hopefully respectful to people’s time (and, for talent, time is money) and maximizes positive exposure for a film/property.

For all of the above, take this task and then expand it to a global scale. One day, TF1 in France wants to interview on location, the next ProSieben from Germany, and the following NHK from Japan. To handle the world, there will often be regional press junkets, which may mean at least one in Europe and one in Asia in addition to those in the United States. Requests will be coming in from thousands of newspapers and television stations. And worse, if they are not coming in, it is the job of PR to drum up interest and make them come in, whether that means seeding stories, pitching angles to publications and journalists, or creating special tie-ins. All of this activity needs to happen on a massive scale in a compressed time frame. The incremental budget costs are labor and travel.

In the end, with the global reach of the Internet, and so many new applications in the digital age such as EPKs, it is fair to ask the question whether overall the Internet is a friend or foe to PR. It is a valid concern, given the danger of leaks that can lead to ubiquitous access and news versus the ability to disseminate a message almost instantly to everyone simultaneously around the globe. I asked Lynn Hale, George Lucas’s head of PR at Lucasfilm since the 1980s, what she felt about the Internet on balance:

It cuts both ways, although overall I would say that the Internet is a friend. On the one hand, the Internet makes it impossible to keep secrets. I doubt that George could have ever pulled off the surprise of Darth Vader’s revelation if The Empire Strikes Back were released today, or if the Internet had been around in 1980. But on the other hand, the Internet has given us an instant worldwide platform to immediately disseminate news. Lucasfilm learned early on the power of the Web, and we embraced it. As early as 1998, we were reaching out directly to our fans, providing information that wasn’t necessarily of interest for conventional news outlets. Back when we were releasing Episode I, www.starwars.com listed theater locations that would be showing the teaser trailer. Fans flooded into theaters in such huge numbers that it became news. Local stations reported on it, and even the late-night shows—like Letterman and Leno—included comments in their opening monologues. It was unprecedented at the time, but now movie studios rely heavily on the Internet to create excitement around a film’s opening. It’s another piece of the puzzle, and another tool at our disposal.

Screenings

To make sure that influential people can be impressed by the film and help spread the word, PR will work closely with distribution regarding screenings. Screenings have a wide range (charity, partners, press, critics, word of mouth, theater chains), and PR has the direct responsibility for ensuring that press screenings are effective. These screenings tend not to involve additional expense beyond the screening costs, but it is important to make the best possible impression on the critics/audience who will be reviewing (and potentially writing about) the film. Accordingly, efforts may be made to ensure high-quality venues, with good sound, picture, and ambiance. PR can only do so much to influence reviews, but at its core one of the jobs of PR is to try to positively influence the outcome and put the film in the best possible light.

Media Promotions

Another category driving awareness is media promotions. This can involve a variety of stunts or giveaways, with radio station contests (and film-based prizes) a common vehicle. The key with these types of promotions is to secure additional media weight, and thereby impressions, by creating a contest, quiz, or similar interactive event engaging consumers with the property.

Exhibitor Meetings

The distribution and exhibition communities have two major U.S. conventions per year, Show East (Florida, moving between Orlando and Miami) in the fall and Show West (Las Vegas) toward the end of March. (Note: There is also CineExpo in Europe, formerly in Amsterdam, and more recently held in Barcelona.) Distributors use this opportunity for a dog and pony show for theater owners, getting them excited about their upcoming releases. If a producer or studio has already released its trailer, it may use this opportunity to create a separate short piece to show the theater owners.

These markets provide a significant marketing opportunity for the distributor, and depending on the film either the director, producer, or key stars will attend to introduce the movie. This can be “showbiz” at its best: packed audiences waiting for a first look at a film, with press clicking photos of the stars present just to create chatter and excitement.

In the spring of 2005, the atmosphere was electric at Fox’s presentation between the photographers’ feeding frenzy clicking pictures of Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie walking out together to promote Mr. & Mrs. Smith, and the entrance of Stormtroopers together with George Lucas to highlight the release of what was then believed to be the final Star Wars movie. (Note: Influenced by the severe economic downturn starting in 2008, these annual events have been toned down by many studios.)

Film Markets and Festivals

There are a variety of major international festivals, which serve as outlets to debut films, gain publicity, and screen films for potential distribution pickup/acquisition.

There are literally markets all the time, but those shown in Table 9.4 are examples that have risen to “major” status (timing is approximate, as dates tend to shift over time).

The impact of independent festivals is significant, as they provide an outlet beyond the studio gatekeepers, and have proven their ability to launch directors, stars, and hits. It is now roughly 25 years since Steven Soderbergh debuted Sex, Lies and, Videotape at Sundance (winning the dramatic Audience Award), prior to the film going on to win the Palm d’Or in Cannes and catapulting both the director and actress Andie MacDowell into stardom. More recently, Slumdog Millionaire’s Best Picture award in Toronto was a precursor to its capturing the Golden Globe for Best Picture and winning the Oscar for Best Picture (2009). Part of the problem with success is that what were once independent festivals intended to provide opportunity and expression for independent filmmakers have become so influential and competitive—with studios trolling to pick up properties for distribution—that the festivals have been swamped with submissions and inadvertently become another kind of gatekeeper.

Table 9.4 Festival Locations and Timing

Festival |

Location |

Timing |

Sundance |

Utah |

Winter |

AFM |

Los Angeles |

Fall |

Cannes |

France |

May |

Venice |

Italy |

Fall |

Toronto |

Canada |

Fall |

In addition to impacting advertising (online expenditures and targeted campaigns), PR, and trailer exposure, the digital and online worlds are profoundly influencing marketing efforts via project-specific websites. Now, not only do producers need to think about reserving titles, but as soon as a project matures it is wise to reserve the related domain name (a common word or title may be translated into a phrase such as www.XYZmovie.com).

Websites need to be built, and the timing of launch, sophistication of site, and budget will all influence the end product. For an event-type movie, there may even be pressure to build the site well in advance as a place for fans to visit during production. This can seed interest and create early buzz. If a director is willing, the website can even be a place for production journals or a regular director blog from the set, as was the case with Peter Jackson during the making of The Lord of the Rings films, and more recently with the production of The Hobbit, where regular blog updates could be found (www.thehobbitblog.com).

As with a trailer, however, building a website in advance of a release can be challenging, for there may be little or no new material to post initially. When Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull was announced, there was enthusiasm for updating the older Indiana Jones site; however, until new production commenced there were few new key assets that could be posted. Nevertheless, the site became (as are all film sites) a place to post new news, the oldest and simplest function of film/TV sites.

As noted earlier, it is now commonplace to be able to go to a film or TV show’s website and see the trailer or other preview of the product. Moreover, the trailer is now “networked” such that it can be found not only on the film’s dedicated website, but linked to review sites and theater listings. A few years ago, if you missed a trailer in the theater, you may never see it, but today you can catch it in a variety of locations, replay it, and even link it/e-mail to a friend via a social networking site creating a viral network buzz. For every studio executive complaining about the availability of its programming on video sites without authorization, there seems a counterbalancing marketing guru eager to take advantage of the platform to widen distribution of trailers, etc. The potential to distribute trailers to target demographics and allow sharing of trailers (or even elements thereof) on social networking sites adds another toolset to the marketing executive (see further discussion below, including “Online Marketing: Expanding the Toolset”, page 548).

Beyond News and Trailers: Interactivity

A powerful feature of websites is their ability, beyond posting news and showing trailers, to market a property by more deeply engaging users/fans. Today, with video functionality common online, websites can host a variety of elements, including behind-the-scenes shots, interviews with key cast and crew, Web documentaries (e.g., of a making-of nature), webcam feeds, and live chat video chats. For Star Wars: Episode III, Lucasfilm created a series of Web documentaries, such as behind the scenes of creating lightsaber battles and the genesis of creating the villain General Grievous; these included footage of George Lucas approving iterative design elements, interviews with artists at Industrial Light & Magic, and shots of behind-the-scenes green-screen shoots.

In addition to video elements, websites may contain mini-games, links to e-commerce sites, links to promotions and promotional partner sites, and downloadable elements for instant gratification. Everyone loves getting things for free, and often sites will allow certain downloads of screensavers, buttons, etc. The cross promotion between online engagement and watching can be very significant for a franchise. Tom van Waveren, former head of Egmont Animation (Denmark), creator and producer of Cartoon Network hit Skunk Foo, and producer of hit animated reality show Total Drama Island, told me the following regarding the interaction of kids engaging online and watching Total Drama Island:

What makes Total Drama Island unique is both its teen skew as an “animated reality show” and its online extension on Total Drama Island: Totally Interactive. On Total Drama Island: Totally Interactive, which was accessible on the Cartoon Network website, each episode’s challenge to the contestants is mirrored by a casual game and viewers can create their own avatar to play such games. Two things were remarkable about Total Drama Island: Totally Interactive. First of all, we were overwhelmed by the response we got to the site, and had two server crashes in the first week trying to match our capacity to demand of peaks of over 100,000 simultaneous users from the first month. By the time of the season finale, over 3 million unique avatars had been created and being regularly used. And second, we could see a pattern evolving between the viewing figures on air and the activity peaks online. Comparing our data, we could see that 10 percent of the viewers were simultaneously watching a new episode and online playing the games with their avatar. This demonstrated that the world of Total Drama Island was, at least to 10 percent of our audience, a multitasking, multiplatform entertainment experience instead of a TV show or an online game. One experience on several platforms simultaneously.

Trying to learn from this experience, we are looking at how we can create equally fluent transitions from one platform to the next with our other properties. This means that all the codes of the on air world need to be respected online and that the nature of the content offered online is closely connected to the on-air experience.

(Note: The finale of Total Drama Island broke Cartoon Network records, including, at the time, setting a new record and becoming the top telecast among tweens 9–14 for the network.)

The search to create synergies by crossing over media, whether by interacting with content via the Web or a mobile phone, is now even driving the nature of the programming. When millions of viewers text message a vote on American Idol, they are deeply engaged in the content, and producers are ever seeking clever ways to add interactive components (e.g., text message, vote online) to linear programming.

Finally, one great benefit to website marketing is its duration: where most marketing comes and goes (e.g., TV spots), a website is persistent, reaching back in time before a show/film launches to help seed interest, reaching maturity during product launch and offering depth of content, from trailers to interactive features, and remaining available through downstream exploitation allowing complementary marketing to long-tail revenue streams. Depending upon the size of the franchise, there may be periodic updates with key launches, such as with a video release (describing elements of bonus materials, and maybe even some extra features that can only be unlocked with the purchase of a DVD), or re-promotion of titles (e.g., box sets, TV specials).

Social Networking—Sites and Microblogs