CHAPTER SEVEN

INTRODUCTION

A major income generator for sports enterprises is the facility where teams play or events are held. This is also often a revenue source for the municipalities in which these teams play. It can also be a huge expenditure for the parties involved. The importance of a quality facility to the financial success of a sports franchise is now clearly appreciated by all parties involved. The opening of a new or heavily renovated facility is a transformational moment in the business of a sports franchise. This moment has already occurred for the majority of professional sports franchises, with approximately 80% of MLB, NBA, NHL and NFL teams doing so since 1990. Although the building boom for the current generation of facilities is largely over, and franchise owners have turned to the creation and exploitation of other revenue streams, there can be no doubt that what is past is prologue and that a construction era will begin anew when the current generation’s state-of-the-art facilities are deemed obsolete at some point in the future. The most recent trend is for teams to try to make the facility part of a larger real estate play, with a mixed-use sports, commercial, residential, and entertainment development incorporating the playing facility, retail stores, hotel and residential housing, restaurants, and other entertainment options. AEG’s L.A. LIVE in Los Angeles is the best example of this to date. More on this is discussed in Chapter 6, “Teams,” and Chapter 11, “Sports Franchise Valuation.” The focus here is on the major sources of revenue and the major political issues associated with sports facilities.

From a leadership perspective, the broad scope of the successful sports venue is not complex. The first priority is to ensure that the facilities generate revenues; the second is to ensure that a substantial portion of that revenue stream goes to the sports owner or promoter—that is, of course, unless you represent the municipality. The direction of revenue streams is the main focus of the complex negotiations between teams and the venue owners.

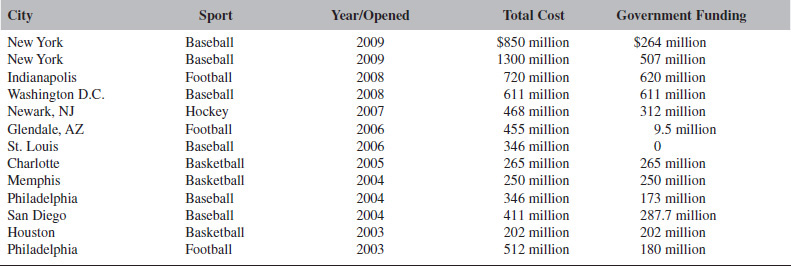

The understanding of this formula has evolved as the burden of the construction of facilities has shifted from initially being a largely private task, to a predominantly public expenditure, to the current mix that exists in most instances today with various forms of public and private partnerships. Public contributions are much harder to come by today than they were in the earlier phase of the most recent building boom. The taxpayers in the cities where a public contribution towards the facility construction is sought are now seeking a clearer understanding of the return they receive on their sports facility investments. This has led to an increase in the aforementioned public–private partnerships, with the teams paying for an increasingly substantial part of the facility construction costs—an obligation that causes them to incur significant debt. The ever-escalating facility construction costs have made these public–private partnerships more of a necessity. The cost is simply too high for most parties to take on entirely on their own. The municipality has higher-order priorities, and many of the teams do not have the necessary funds. Interestingly, in the NFL, a league-funded initiative (the G-3 stadium plan) typically contributes to the team’s share of the construction costs, up to $150 million. (See Table 1 for recent stadium costs and Chapter 5 for a more elaborate discussion of the G-3 stadium plan.)

Franchises often pursue new facilities or renegotiate leases in pursuit of additional revenues. The revenues that have increased most dramatically in importance are those that are not shared with other teams via league-wide revenue-sharing plans. These important revenue sources include luxury boxes, naming rights, and signage.

The excerpts from The Stadium Game lay out the major revenue-generating streams these facilities create. Here we highlight some of the major sources. The distribution of the various revenue streams between the tenant team(s) and landlord municipality are the subject of the stadium lease negotiations previously noted. “The Name is the Game in Facility Naming Rights” focuses on one of the most important revenue streams—facility naming rights deals. We highlight this source separately because of the dominant role it plays. Facilities with names such as Enron, Adelphia, CMGI, PSINET, and TWA—companies that no longer exist or toil in bankruptcy—add an additional element that both sports and corporate leadership should be aware of in marrying the two sectors. This was highlighted even further during the 2009 economic downturn when corporations were left to justify sponsorship investments, including sports facility naming rights. The prime example of this dilemma was Citi Field in New York, a naming rights obligation of $400 million over 20 years for a corporation receiving hundreds of billions of dollars in a government bailout. This left many taxpayers wondering if their dollars should be used for sports sponsorship.

The chapter closes with three pieces that focus on the policy dilemma stakeholders confront in the “who should pay for it” decision-making process. The first, by Marc Edelman, “Sports and the City: How to Curb Professional Sports Teams’ Demands For Free Public Stadiums,” provides an in-depth history of this subsidy issue. This is followed by two pieces of Congressional testimony, one by Neil Demause, a long-time follower of this issue, and the other by Professor Brad Humphreys.

FINANCING AND ECONOMIC BACKGROUND

THE STADIUM GAME

Martin J. Greenberg

FINANCING OVERVIEW

The financing of sports facilities has recently garnered considerable attention. Sports facilities have become increasingly important components in the public finance marketplace with many state and local governments aggressively trying to keep or lure sports franchises into their communities…. there has been an explosion in the number of financing projects for stadiums and arenas, as communities have made plans to build state-of-the-art facilities to attract and retain professional franchises and draw major sporting events.

Fueling this development explosion is league expansion, facility obsolescence and a demand for increased franchise revenue. Since 1990, there have been seventy-seven major league facility lease re-negotiations, stadium renovations, or new venues built for professional football, baseball, basketball, and hockey at an approximate cost of $12 billion.

….

Since 1990, thirty-seven new stadiums and arenas—worth more than $6.5 billion in construction costs—have opened. By 2000, more than half of the country’s major professional sports franchises were either getting new or renovated facilities, or had requested them. [Ed. Note: As of 2010, approximately 80% of the teams in the NBA, NFL, NHL, and MLB were playing in facilities that have been either constructed or heavily renovated since 1990.] This increase in sports facility construction is expected to continue throughout the decade [2000s] as league expansion and the underlying economics of the sports industry evolve.

The evolution of stadium and arena financing can be divided into four distinct periods: the Prehistoric Era dating back before 1965; the Renaissance Era carrying through 1983; the Revolution Era occurring between 1984 and 1986; and finally the New Frontier Era, from 1987 until today….

The Prehistoric Era: Prior to 1965, the sports industry was not quite the big business that it is today. Government financing was the only source of funding. The most common funding instrument was general obligation bonds. [Ed. Note: Wholly privately financed stadiums can be found in this era as well.]

The Renaissance Era: From 1966 to 1983, the popularity of professional sports grew tremendously in terms of both live attendance and television viewership. Franchise owners saw the values of their sports investments grow dramatically. The financial performance of arenas and stadiums improved through increased utilization by other events, such as concerts and family shows. Financing for the facilities continued to be dominated by the public sector.

During this era, bonds secured by taxes were the most traditional approach to stadium and arena financing taken by the public sector. In this situation, the municipality (city, county, state, or other government entity) backs a bond issue with a general obligation pledge, annual appropriations, or the revenues from a specific tax.

The Revolution Era: The Deficit Reduction Act of 1984 and the Tax Reform Act of 1986 both had large implications on stadium and arena financing. Many of today’s older facilities were financed on a tax-exempt basis prior to the Tax Reform Act of 1986.

The Deficit Reduction Act lowered the priority of constructing public assembly facilities using funds from the public sector in light of the need to lower the national deficit. The Tax Reform Act made it much more difficult to finance stadiums and arenas with tax-exempt bonds. As a result, financing structures became more complex as revenue streams are often segregated to support multiple issues of debt in both taxable and tax-exempt markets.

New Frontier Era: Since 1987, stadium and arena financing has embarked upon a fascinating new path. The days of “vanilla” financings are over, giving way to greater complexity in financing arrangements. In addition, the planning and construction period has been stretched to a five to ten year time horizon. “Typical” construction risks, voter approval, and political “red tape” associated with the public’s participation in stadium and arena financing projects have caused significant delays and have put the financial feasibility of some new facilities in doubt.

Most deals now involve partnerships between multiple parties from the public and private sectors. These mutually beneficial public/private partnerships are dictated by what each party can bring to the table. The public sector may be able to provide any combination of land, public capital/revenue streams, condemnation, infrastructure improvements, and tax abatement. The private sector may likewise provide any or all of the following: land, investment capital in the form of debt or equity, acceptance of risk, operating knowledge, and tenants.

Private sector participation in financing structures has typically been through taxable debt secured by the facility’s operations and/or corporate guarantees. This is a relatively expensive source of funding that has generally required a higher debt coverage ratio and significant equity contributions. Thus, the private sector has sought other nontraditional sources. Those can include luxury suites, club seats, personal seat licenses (PSLs), concessionaire fees, and naming rights, among others.

The unique background and political environment surrounding the financing and construction of professional sports facilities plays a critical role in shaping the appropriate financing structure. The changing economics of professional sports has led franchises to demand a greater share of facility-generated revenue. As a result, reliance solely on public bond financing has become increasingly difficult and a combination of both public and private participation is often the cornerstone of current financing structures.

FINANCING INSTRUMENTS

Stadiums and arenas have been financed through a variety of public and private financial instruments. Because sports facilities represent a significant capital investment and provide benefits, both economic and social, to the public, financing structures typically rely on a combination of public and private financing instruments. These structures can become complex, particularly when traditional landlords and tenants form partnerships to provide capital for the facility. The appropriate financial instruments depend significantly on the unique circumstances surrounding the particular project.

Defined Instruments

Municipal notes and bonds are publicly traded securities. Congress exempted municipal securities from the registration requirements of the Securities Act of 1933 and the reporting requirements of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. However, anti-fraud provisions remain in effect for any offering circulars issued to prospective investors.

Congress has not regulated issuers of municipal securities nor required that they issue a registration statement for several reasons. Among these reasons are the desire for government comity, the absence of recurrent abuses, the greater level of sophistication of marketplace investors, and few defaults. Municipal bonds are often analyzed by rating agencies such as Fitch, Moody’s, and Standard & Poors. The key factors considered by rating agencies, credit enhancers, and investors in analyzing tax-secured debt include:

• Level of coverage;

• Broadness, stability, and reliability of tax base;

• Historic performance of revenue stream;

• Appropriation risk;

• Underlying economic strength;

• Political risk; [and]

• Financial viability of the project.

[Ed. Note: See Chapter 11 for further discussion of the credit-rating process.]

The following are descriptions of common financial instruments used to fund sports facilities.

General Obligation Bonds: General obligation (G.O.) bonds are secured by the general taxing power of the issuer and are called full faith and credit obligations. States, counties, and cities are common issuers of this form of debt. Repayment of the debt comes from the entity’s general fund revenue, which typically includes property, income, profits, capital gains, sales, and use taxes. The full faith and credit pledge is typically supported by a commitment from the government issuer to repay the principal and interest through whatever means necessary, including levying additional taxes. In addition, double-barreled bonds are issued and secured not only by taxing power, but also by fee income that is outside the issuer’s general fund. G.O. bonds secured by limited revenue sources such as property taxes alone are called limited-tax general obligation bonds. This type of bond typically requires legislative or voter approval.

Since G.O. bonds are backed by the general revenue fund of the issuing instrumentality, they usually represent the issuer’s lowest cost of capital. General obligation bonds, however, are becoming increasingly difficult to issue for sports facilities with a growing demand on government for other capital projects and services.

Special Tax Bonds: These bonds are payable from a specifically pledged source of revenue—such as a specific tax—rather than from the full faith and credit of the municipality or state. Tax and Revenue Anticipation Notes (TRANs) are issued for periods from three months to three years in anticipation of the collection of tax or other revenue. Similarly, TRANs are issued in anticipation of a bond issue. Tax-exempt commercial paper is issued for thirty to 270 days, and typically is backed by a letter of credit from a bank or a bank line of credit. These are all used to even out cash flows when revenues will soon be forthcoming from taxes, revenues, or bond sales.

Revenue Bonds: Revenue bonds are more complex and less secure than general obligation bonds. Revenue bonds are typically project specific and are secured by the project’s revenue, income, and one or more other defined revenue sources, such as hotel occupancy taxes, sales taxes, admission taxes, or other public/private revenue streams. The debt service (principal and interest) is paid for with dedicated revenue.

Since revenue bonds limit the financial risk to the municipality, they typically have a lower credit rating. The more stable and predictable the source of revenue, the more credit-worthy the bond issue. Naturally, revenue sources with an existing collection history are preferable to underwriters and rating agencies, but revenue bonds do not offer that predictability.

Lease-Backed Financing (Lease Revenue Bonds): This financial instrument still benefits from the credit strength of a state or local government. An “authority” typically issues bonds with a facility lease arrangement with the governmental entity. The government leases the facility from the authority and leases the facility back to the authority pursuant to a sublease. The lease typically requires the government to make annual rental payments sufficient to allow payment of the debt service on the authority’s bonds. There are several related lease structures including Sale/Leaseback and True Lease arrangements.

Certificate of Participation: Certificates of Participation (COPs) have become an increasingly common financial instrument used to finance sports facilities. COP holders are repaid through an annual lease appropriation by a sponsoring government agency. COPs do not legally commit the governmental entity to repay the COP holder, and therefore generally do not require voter approval. In addition, COPs are not subject to many of the limitations and restrictions associated with bonds.

Although COPs offer the issuing authority less financial risk and more flexibility, they tend to be more cumbersome due to the reliance on the trustee. In addition, COPs carry a higher coupon rate relative to traditional revenue bonds.

[Ed. Note: The author’s examples of applications of the financial instruments described are omitted.]

….

Economic Generators

The creation and expansion of sports facility revenue generators has been one of the driving forces behind the sports facility boom in the 1990s. These new revenue generators are joining traditional income sources such as concessions, parking, and advertising in determining whether the lessor or the lessee will earn a profit at the facility. Thus, the allocation of revenues derived from items such as club seats, seat licenses, corporate naming rights, restaurants, luxury suites, and retail stores is quickly becoming an important part of every sports facility lease agreement.

This … is an examination of the primary revenue generators and how these items are currently being addressed in major and minor league sports facility lease agreements.

Club Seats

Club seats were the invention of former Miami Dolphins’ owner Joe Robbie who created a new level of premium seating in hopes of securing enough funding to privately finance a new home for the Dolphins. Robbie placed 10,214 wide, contour-backed seats in the middle tier of the three-tiered facility and dubbed them, “individual club seats.” The seats, which cost from $600 to $1,400 annually, had to be leased on a ten-year basis. In return, club seat patrons received twenty-one-inch-wide seats, overhead blowers puffing cool air on them during hot days or nights, and access to an exclusive series of lounge areas that were finely decorated and serviced by wait-staff ready to handle the patrons’ concessionary needs. With the guaranteed revenues from the ten-year leases for the club seats and luxury suites in hand, Robbie was able to secure the financing necessary to build the facility that was later named in his honor and assumed a place in the stadium financing annals.

Since its inception in the mid-1980s, club seating has become one of the largest revenue producers for stadiums. And since 1991, the number of leased club seats has risen by more than 500 percent, producing a significant and steady revenue stream for the four major league professional sports teams….

Luxury Suites

In 1883, Albert Spalding’s new baseball stadium for the Chicago White Stockings catered to the upscale fan by offering eighteen private boxes furnished with drapes and armchairs. Since then, professional sports franchises have continued their race to install luxury suites in their playing facilities.

Luxury suites have entrenched themselves as the second-most important revenue stream for professional sports franchises behind television revenues.

….

Personal Seat Licenses

In Tampa Bay, Buccaneers owners used it to finance the National Football League team’s sparkling new stadium. On campus at the University of Wisconsin, Badgers’ officials are using it to help fund the school’s athletics program….. [Ed. Note: The Philadelphia Eagles, Houston Texans, and the New York Giants and Jets have used them more recently.] and thereby join ten other NFL teams (Baltimore, Carolina, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Dallas, Oakland, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, Tampa Bay, and Tennessee) that have variations of them.

It is a personal seat license, or PSL, one of the most important—and often misunderstood—of the legal and financial vehicles available for sports stadium funding.

Although there has been a greater increase in private sector contributions to sports stadium and arena development, teams and communities continue to seek new ways to finance stadiums. Personal seat licenses have provided, at least in some instances, another means of contributing to the private equation in the facilities partnership formed between private financiers and public funding.

In addition to providing private sector funds for the construction of sports facilities, personal seat licenses also have generated season ticket sales and facility revenues, and have been used as a means to attract teams contemplating relocation.

The expanded use of seat licenses seems beneficial for all parties involved [in the] financing process of sports facilities. Teams receive upgraded facilities and guaranteed ticket bases, which should allow them to remain competitive on and off the field for many years. Fans receive property rights in their personal seat licenses, which can become valuable items on the open market. And governmental entities receive the benefits of upgraded or new sports facilities at reduced costs to taxpayers, theoretically allowing these entities to allocate tax monies for essential governmental services.

The stadium financing effort in the Carolinas for the home of the Carolina Panthers is an example of the interaction between seat licensing revenues and governmental interests. Ericsson Stadium, the $248-million home for the NFL’s expansion Carolina Panthers opened in 1996, was built at a cost to taxpayers of $55 million, while the rest of the financing for the facility was derived from seat license revenues. The Panthers were projected to have a $200- to $300-million impact on the Carolina economy, easily generating enough of a return to cover the initial taxpayer investment.

….

Funds for the bulk of the Panthers’ development costs—$162 million (about $100 million after taxes)—came from private seat licenses priced from $700 to $5,400 for season tickets and club seats. Nearly 62,000 private seat licenses were sold by the time the stadium opened, including 49,724 seat licenses and 104 suites (valued at nearly $113 million) a month before the franchise was awarded. Today, 156 of 158 suites (price: $50,000 to $296,000) are leased for six- to 10-year periods.

….

Understanding the PSL

A personal seat license is defined as a contractual agreement between a team (the PSL licensor) and the purchaser (the PSL licensee) in which the licensee pays the team a fee in exchange for the team guaranteeing the licensee a right to purchase season tickets at a specified seat location for a designated period of time (such as five years, ten years, or even the life of the facility) as long as the license holder does not violate the terms of the license agreement. Should the licensee violate these terms, the team automatically gets the personal seat license back, or has the ability to exercise a right to buy back the license at the original selling price and then resell it on the open market.

A personal seat license, which can be resold on the open market, generally offers the purchaser no guarantee of a return on the initial investment—none, of course, except for the benefits of enjoying use of a seat at a game. The main variables in legal constructions of modern personal seat licenses—which also have been called permanent seat licenses—are (1) the cost and (2) the time period of the license.

Variations on the Personal Seat License Theme

Tampa Bay employed a variation of the personal seat license to raise money for constructing Raymond James Stadium, home of the Buccaneers. Fans were asked to pay a deposit for the right to buy tickets for the next ten years. The deposit, which was equal to the price of a season ticket for one year, is to be refunded at the rate of 5 percent per year for nine years, with the balance paid at the 10th season.

The Kohl Center—home of University of Wisconsin hockey and the men’s and women’s basketball teams—has a plan called the Annual Scholarship Seating Program. It calls for season ticket holders to donate to the University Scholarship Fund in exchange for the right to purchase prime seats.

Recently, the Green Bay Packers announced a $295 million plan to renovate Lambeau Field, which would be paid for through a public/private split of 57/43 percent. The team, through a one-time user fee on paid season ticket holders, would raise a total of $92.5 million. Lambeau Field season ticketholders would pay $1,400 per seat and Milwaukee package season ticket holders would be asked to pay $600 per seat. [Ed. Note: The renovation has been completed.]

A one-time user fee differs from a PSL. In Green Bay, the fee paid only entitles the season ticket holder to obtain tickets to renovated Lambeau Field. It does not guarantee the season ticket seat beyond the first season in renovated Lambeau, nor is the right transferable. The Packers are discussing, however, implementing a policy that, if season ticketholders ever surrendered their tickets, the next person on the team’s waiting list would be required to reimburse the user fee to the original ticket holder before any tickets actually changed hands.

In December of 1999, Robert McNair’s Houston NFL Holdings, Inc. unveiled its plan to sell fewer personal seat licenses at a lower price than has been fashionable recently in financing new NFL stadiums. Its goal is to attract a broader demographic to games.

….

Comparatively, 80 percent of the seats in Cleveland Browns Stadium and 85 percent of the seats at Adelphia Coliseum, home of the Tennessee Titans, were subject to licenses. The Steelers sold 50,000 PSLs for Pittsburgh’s new 64,000-seat stadium.

….

Naming Rights

[Ed. Note: For a more extensive discussion of naming rights, see the reading “The Name Is the Game in Facility Naming Rights.”]

One of the most recent additions—and the most lucrative—to the list of stadium revenue generators is the selling of naming rights. Naming rights are currently sold for not only the right to rename an entire stadium, but also to name entryways into the stadium, the field, breezeways, etc.

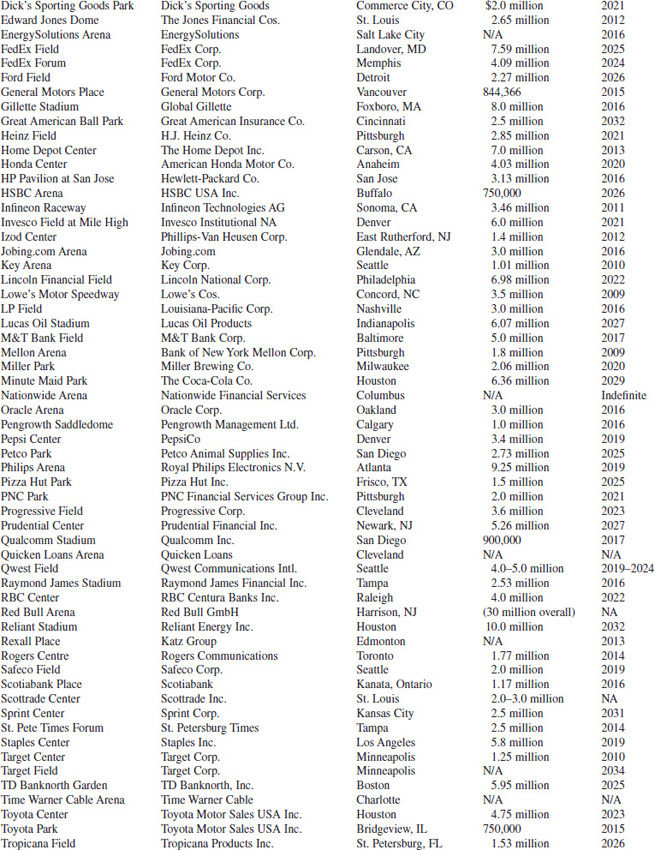

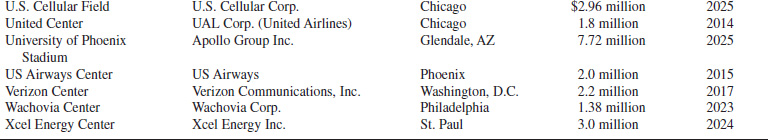

In 1987, the Los Angeles Forum, then home to the Lakers and Kings, became the Great Western Forum when Great Western Bank became the first corporation to purchase the rights to name any professional sports facility. Since then, it has become the rule rather than the exception for a facility to bear the name of a company.

Historically, stadiums and arenas have been named either for a geographic region (Milwaukee County Stadium), in honor of a renowned individual (RFK Stadium), or after the name of the home team (Giants Stadium). Today, the increasing need for capital has resulted in most new facilities bearing the name of an individual company. In fact, the naming rights deals have grown so lucrative, that even storied stadiums such as Lambeau Field in Green Bay are considering the sale of its naming rights in some fashion or another.

The selling of naming rights is a trend that will continue because as time goes on, the revenue it produces is vital to financing venue development and renovations. Jerry Colangelo, [former] owner of the Arizona Diamondbacks and Phoenix Suns, has stated that, “I think you’re going to see more and more corporate involvement in terms of naming rights and major involvements with large companies. In order to deliver that product, the game itself, you need to build venues that have the opportunity to pay for it. Our group is indicative of that trend.”74

….

Beyond Stadium Naming Rights

There are times when a facility chooses not to sell the name of [the] facility itself, but rather sell the rights to name the field, breezeways, or portals into the stadium. This is a very new concept that began in 1999 when the Cleveland Browns christened its new stadium without a corporate naming rights sponsor—by choice. The club chose instead to sell only the rights to name the stadium’s portals at $2 million a year for ten years.

One such company is National City Bank, who receives other benefits with their deal, including:

• The right to call themselves the “Official Bank of the Cleveland Browns” for five years while serving as the team’s sole bank provider;

• The right to use the Cleveland Browns logo in conjunction with various advertising and promotional activities;

• Maintain the right for product merchandising for several unnamed existing products, as well as several new products;

• Name identification in the southeast quadrant (presumably the gate with the most public exposure) of the new stadium, including logos on all turnstiles, entranceways, directional signage, tickets, and seat cup holders;

• A permanent presence in the west end zone scoreboard; [and]

• Numerous other signage rights throughout the stadium.

… In the case of Soldier Field, selling naming rights to auxiliary areas will be the only option to generate this type of revenue because the overall naming rights of the stadium are not for sale. Chicago Mayor Richard Daley recently stated publicly, “(The stadium) will always be known as Soldier’s Field. That is dedicated to the veterans here in Chicago. It will always be that.”165

But selling the rights to the auxiliary facility areas is not limited only to those facilities that choose not to sell their overall naming rights. When the Patriots sold the naming rights to their new field for $114 million-plus over fifteen years to CMGI—an Internet holding company with affiliations and financial interests with 70 Internet companies—the Patriots reserved the right to additionally sell the rights to the stadium’s entrances, which is expected to earn the team millions more on an annual basis, based on the Cleveland deal.

These auxiliary areas can even include seating sections. At Bank One Ballpark [now Chase Field], for example, Nissan struck a deal with the Arizona Diamondbacks to name the premium seating level the Infiniti Level. Nissan’s annual price tag for that right actually exceeds the $2.3 million paid annually by Bank One for the facility’s naming rights deal, although Bank One’s deal included several other options bringing its annual commitment to $4.6 million per year.

And naming rights are not limited to the game-day field only. The Indianapolis Colts recently announced that they sold the rights to their practice facility to Union Federal Bank. The venue will be known as Union Federal Football Center. Although no price was announced, team officials said it was the largest sponsorship deal in the team’s history. The package includes radio spots, sponsorship of the team’s fan club, signage in the RCA Dome, and print advertising.

….

In the most recent Houston deal with Reliant Energy, the deal also called for Reliant to maintain the naming rights to the Astrodome Complex, which includes the Astrodome, the AstroArena, and a new convention center.

Parking

Of the main economic generators discussed … parking revenue continues to remain the smallest revenue generator of this group. As a result, parking—in a strictly financial sense—is not usually the most significant issue during lease negotiations between teams and sports facilities.

….

Advertising

It may appear as though sports teams have a new interest in advertisements and sponsorships…. years ago, nearly all stadiums bore the names of famous people or cities. These days all but a handful carry the names of companies willing to pay millions to have a corporate logo identified with a team and its hometown stadium.

It is not so much that it is a new revenue source, however. Instead, it is the ability of teams to keep this revenue that is making advertising the goose that laid the golden egg. In the NFL, for instance, advertising and signage revenue is exempt from the league’s revenue-sharing program.

The demand for advertising has turned every square inch of a sports facility into a potential source of advertising income. Advertising consists of everything from signage on the outside of arenas to sleeves that cover the turnstiles to posters above the urinal.

For the Washington Wizards, the …MCI [now Verizon] Center will earn more than $6 million from signs alone, a 100 percent increase over US Airways Arena. The Washington Redskins earned approximately $250,000 in advertising income during the team’s final season at RFK Stadium, a figure ranked near the bottom of the NFL. When the team moved in to Jack Kent Cooke Stadium, the new home of the Redskins, advertising industry specialists believe advertising revenue climbed to between $6 million and $8 million a year from sponsorships alone.222 That number grew even larger when new owner Daniel Snyder sold the naming rights for the stadium to Federal Express.

These examples of the boost advertising can give to team revenue are not uncommon. Generating revenue that a team can keep for itself has become a necessity for teams to keep up with climbing player salaries.

Stadium advertising has become necessary to maintain a profitable franchise.

….

Concessions

Concession rights are rights transferred to a concessionaire for the sale and dispensing of food, snacks, refreshments, alcoholic and nonalcoholic beverages, merchandise, souvenirs, clothing, novelties, publications, and other articles in the stadium or arena, pursuant to a concession agreement. The concession agreements set aside sales spaces which include concession stands, condiment areas, vending machines, hawker’s station, the press room, the stadium club, cafeterias, executive clubs, executive suites, food courts, outdoor cafés, and waitress service for club seats, among others. Either a team or facility owner hires the concessionaire. The concession agreement will normally grant a concessionaire the exclusive right to exercise concession rights in concession spaces throughout a facility.

Wes Westley, President and CEO of SMG, has said:

“In the past, facilities relied solely on the success of concession stands. With ‘state of the art’ arenas and stadiums being built, emphasis is now placed on luxury box and club seating, catering, restaurants, hospitality suites, and other nontraditional concessionaire sales. In addition, branded foods and franchising has also impacted the amount of gross sales being generated. Simply stated, there’s now a much greater pie of revenue to share.”388

This shift has dramatically increased total gross sales at all new venues. Today’s concession contracts include commission payments on specific types of sales rather than on total sales. New contracts may have as many as 15 different sales categories in which various commission rates are paid.

….

Other Economic Generator Provisions

At a time when sports teams are looking to meet the demands of increasing player salaries and still provide a growing income stream to owners, alternative sources of revenue are becoming increasingly important and popular.

Everything from restaurant operations to sports amusement parks are developed to create excitement about the team and generate revenue in the process. While stadium tours and team retail stores may only provide a few thousand dollars to the annual income statement, they often go a lot further in keeping teams at the top of the mind of fans.

The more interesting development is that there appears to be little or no uniformity among how these programs are developed or how they are implemented. While most restaurants, for instance, are operated by a concessionaire, some leases send the revenue to the team, while others give it to the district.

The same is true of tours. Some new stadiums are offering them and raking in revenue, while others never even opened the doors to paying tour groups. And then there is the Grand Dame of stadiums, The Louisiana Superdome, which is expanding its tours even though it is more than two decades old.

What is clear, however, is that ancillary revenue is increasingly important, whether it goes to the teams or the stadium districts.

Restaurants

Restaurants are becoming an important part of making stadiums a constant attraction, even when there are no games scheduled. The Southeast Wisconsin Professional Baseball Park District proved this when it allowed for the completion of the Klements Sausage Haus, a freestanding restaurant, even after the opening of Miller Park for the Milwaukee Brewers was delayed for a year because of a construction accident.

The Milwaukee Brewers have started using the Sausage Haus, which is currently open during games, for press events. The team, for instance, introduced its new skipper at the restaurant. The restaurant stands adjacent to Miller Park.

The District’s lease agreement with the Brewers calls for the facility to be operated by an outside vendor, with revenue from the restaurant to go to the Brewers.445

Like many new stadiums, the Brewers’ Miller Park also features several restaurants, all of which will be operated by SportService, Inc.

In addition to the Klements Sausage Haus, Miller Park will have a sports bar and restaurant, which is scheduled to be open all year. It will also have a high-end restaurant near the luxury boxes, which will be open only during games and for special events.

The goal is to allow fans to use baseball games for all sorts of entertaining. The restaurant facilities are capable of hosting everything from a business meeting to a birthday party.

The Brewers retain all of the revenue from the restaurants.

The St. Louis Rams also collect all of the revenue from the restaurant at the TransWorld Dome [Ed. Note: now known as the Edward Jones Dome.].448 The only time the Rams do not collect the revenue from the restaurant is when the St. Louis Convention and Visitors Commission, which operates the … Dome, hosts an event at the restaurant. That money goes to the commission.

The Rams, however, are also responsible for all the costs associated with the restaurant.

The Miami Heat have yet another arrangement. The team gets all revenue from the restaurants during its games and 47.5 percent of the revenue from all other concessionaires operated during Heat games.

The Colorado Rockies’ lease gives the team 97 percent of year round bar and restaurant revenue if the team uses the facility’s approved concessionaire. If the team chooses another operator, its percentage drops to 95 percent.450 The District collects the remainder of the revenue.

Revenue, however, is not the only concern of a team when it comes to food served at stadiums. Teams have started specializing in regional delicacies in an effort to make the food more interesting and thus increase sales.

The Baltimore Ravens offer Maryland’s famous crab cakes, Latin food is common … in Miami, and sushi is a regular offering in San Francisco at Pacific Bell [Ed. Note: now AT&T] Park.

The theory is that improved gastronomy will increase the amount of money spent at the ballpark…451

Along with local specialties, however, some ballparks are favoring national chains that will bring in diners all year. Both Bank One [now Chase Field] Ballpark, home of the Arizona Diamondbacks, and the Texas Rangers’ Arlington ballpark are home to TGI Friday’s restaurants.

Reservations at the Rangers’ Friday’s restaurant include the price of a ticket to the game and offers seating on three levels, with pool tables and darts serving as a diversion from the baseball game.

Freestanding restaurants, whether as part of a national chain or with a local flair, are almost a requirement for a new ballpark intended to keep the interest of fans, according to Stan Kasten, [then] chairman of Philips Arena in Atlanta.

Facility Tours

Enron Field [Ed. Note: the former name of Minute Maid Park], the home of the Houston Astros, has a fancy coal-fired train, but no tours. Neither does the shiny new Cleveland Browns Stadium. In San Francisco, however, Pacific Bell [AT&T] Park charges $10 a head for tours. The revenue from the tours goes to the team.

The two stalwart stadiums of the NFL still lead the league in tour revenue.

Lambeau Field, which only offers tours from June to August, takes an average of 12,500 fans from the press box to the field each summer. The tours begin at the Packers Hall of Fame on the same grounds as the stadium and take upwards of 90 minutes. Brown County operates the tours and collects about $6 per person. The Green Bay Packers collect the revenue, according to the team.

The Louisiana Superdome collects $7.50 per person for tours and all of the revenue goes to the stadium district. The Superdome, however, developed a special tour of the engineering marvels of the stadium in 1999. Those tours are only offered for groups and prices vary depending on the size of the group and the amount of interest the group has in seeing the underbelly of the stadium.

The Maricopa County Stadium District collects all of the revenue from tours … in Phoenix. Tickets to the … tours are $7.50.

What makes the Superdome and Lambeau Field unique, however, is that most stadium districts find enough demand to justify having a tour staff for up to five years. After that, few fans are interested in touring the stadiums. It is the uniqueness and history of these two facilities that continue to draw the interest of fans.

While younger facilities eventually lose the allure that makes a tour operation successful, older teams continue to look for new ways to generate both revenue and fan interest.

The Green Bay Packers, with the help of the Brown County Convention & Visitors Bureau, created the Packers Experience, which it runs from June to August. The Packers Experience allows fans to get involved in every facet of the game, mimicking the now familiar Lambeau Leap and practicing the punt, pass, and kick.

Fun and Games

The facility is open during the training camp season and serves, along with the Green Bay Packers Hall of Fame, as part of a destination package for football fanatics.

The revenue for the Packers Experience is divided evenly between the team and the Brown County Convention & Visitors Bureau. The indoor amusement park drew an average of 65,000 visitors each summer in the first two years it was open.

After its first year, attendance at The Packers Experience dropped from 73,000 to 54,000. All of the revenue from the Packers Hall of Fame goes to the Packers. It is open year round and takes in as many as 75,000 visitors a year.

In Denver, the Colorado Rockies and Denver Metropolitan Major League Baseball Stadium District split the revenue equally from the baseball museum at Coors Field. The District gives its portion of the revenue from the museum to the Rockies Youth Foundation.

The real fun, however, is coming from the newest stadiums.

For $4,000, fans can watch a game at Phoenix’s … [Chase Field] from the outfield swimming pool.

The Texas Rangers have a running track, Six Flags water park, children’s center, and baseball museum, all of which are busier when there is no game at the ballpark than when the Rangers are in town.

Perhaps the most controversial of the entertainment venues is the Coca-Cola-sponsored playground at … Pacific Bell Park in San Francisco, shaped like a Coke bottle. Some argue it is a symbol of commercialism finally going too far.

Baseball purists worry that the game is being overwhelmed by all the other attractions at the stadiums, but teams counter that they are only giving fans what they want: a destination rather than just a ball game.

Retail Stores

While teams have always sold their merchandise and retained the revenue from it—t-shirts, puffy fingers, and the like—many teams are now negotiating for retail stores that are open year round at the stadiums. This is all part of making the venue a constant tourist destination.

The Baltimore Orioles, Anaheim Ducks, and St. Louis Rams all have exclusive rights to revenue from their retail stores. The management company that operates The Pond gives the Ducks retail space. The team is allowed to retain 100 percent of the revenue from the sale of merchandise at the store.

The Orioles are one of the teams that have their retail store open all year, even when the team is not playing at Camden Yards, or when it is not baseball season. Like the Ducks, the Orioles retain all revenue from the store.

The Tampa Bay Devil Rays embarked on the most aggressive retail strategy in professional sports when the team designed a full-scale mall with several restaurants into the renovated Tropicana Field in 1997.467

The team paid a portion of the costs for the $85 million renovation, which also included a reconfiguration of the ball field. In return, the Devil Rays collect the revenue from the shopping and dining center.

The mall remains open year round, providing a constant revenue stream for the Devil Rays. The team designed the park so that fans would treat Tropicana Field as a place to spend a day or a weekend, rather than just a game-time destination.

The granddaddy of this concept, of course, is Toronto’s Skydome, which was built more as a destination than a ballpark.

The stadium features a 350-room hotel, the largest McDonald’s in North America, a Hard Rock Café, a health club, movie theater, meeting rooms, and shopping mall.469

… Revenue from the various businesses associated with Skydome is divided between the team and the stadium district. The profits are divided at different rates depending on which venture is contributing to the revenue stream.

CONCLUSION

What has become obvious through alternate forms of revenue generation is that teams are seeking ways to get fans to the stadium as much as they are seeking outside forms of revenue.

Few teams, if any, will say that revenue from restaurants, museums, retail stores, and the like, have saved their budget. What teams are likely to say, however, is that the additional revenue from these ventures allows the team to capture a larger portion of the fan’s wallet. That is what makes sports good business.

References

74. Don Ketchum, “D-Backs Go to the Bank (One) for Stadium Name: 30-Year Deal Continues Trend to Sponsorship,” Phoenix Gazette, April 6, 1995, at C1, and Eric Miller, “Million-Dollar Name: Bank One Ballpark,” Arizona Republic, April 6, 1995, at A1.

165. Mark J. Konkol, “Daley Says Soldier Field Has Right Ring,” Daily Southtown, June 16, 2000.

222. “Clear and Visible Signs of the Times,” The Washington Post, Aug. 24, 1997.

388. Presentation, National Sports Law Institute, “Stadium Revenues, Venues and Values,” October 1995.

445. Southeast Wisconsin Professional Baseball Park lease, p. 12.

448. Amended and restated St. Louis NFL lease by and among the Los Angeles Rams Football Club, the Regional Convention and Visitors Commission, and the St. Louis NFL Corp., Jan 17, 1995, Annex 3, at O.

450. Amended and restated lease and management agreement by and between the Denver Metropolitan Major League Baseball Stadium District and Colorado Rockies Baseball Club Ltd., March 30, 1995, at 18,19.

451. Alexander F. Grau, “Where Have You Gone, Joe DiMaggio? And Where Are the Stadiums You Played In?” Georgetown Science, Technology & International Affairs, Fall 1998, p. 5.

467. Tampa Bay Devil Ray Internet site: http://www.devilrays.com/thetrop/thetrop.php3.

469. Grau, p. 4.

SPORTS AND THE CITY: HOW TO CURB PROFESSIONAL SPORTS TEAMS’ DEMANDS FOR FREE PUBLIC STADIUMS

Marc Edelman

I. THE HISTORY OF PROFESSIONAL SPORTS SUBSIDIES

American communities have not always subsidized the professional sports industry.10 To the contrary, for the first seventy-five years of professional sports, most team owners built their own facilities and covered their own costs.11 By the end of World War II, however, changing demographics led to the start of communities subsidizing professional sports teams.12

A. The Emergence of Public Subsidies

The era of publicly funded sports facilities that continues into today began in 1950 when the city of Milwaukee, unable to secure a Major League Baseball (“Baseball”) expansion franchise, decided to lure an existing team by building a public stadium.13

Enticed by the offer to play in a new, publicly funded stadium, on March 18, 1953 Lou Perini, then the owner of MLB’s Boston Braves, decided to move his team to Milwaukee.14 This move marked the first time since the signing of Baseball’s Major League Agreement in 1903 that a MLB team switched host cities.15

As it turned out, the Braves’ move to Milwaukee greatly improved Perini’s bottom line.16 In addition to a new stadium, Perini inherited a larger fan base that purchased 1.8 million tickets in 1953—more than six times as many tickets as Braves fans bought during the team’s final season in Boston.17

Over the next two years, two other MLB teams, the St. Louis Browns and Philadelphia Athletics, decided to similarly leave shared markets and private stadiums in favor of solo markets and public stadiums.18 The Browns left St. Louis, a market they shared with the Cardinals, in favor of Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium, where they became known as the Baltimore Orioles.19 Meanwhile, the Athletics, a team which shared the Philadelphia market, moved to Kansas City to play in Municipal Stadium.20

In 1958, Brooklyn Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley continued this trend—moving his beloved Dodgers out of Brooklyn and to Los Angeles, another city that had been long trying to land a MLB franchise.21 Unlike the earlier teams that had moved—the Braves, Athletics, and Browns—the Dodgers had regularly drawn large crowds and maintained a loyal fan base while playing in Brooklyn.22 However, by moving the Dodgers to Los Angeles, O’Malley became the beneficiary of a prime chunk of real estate.23

B. The 1960s: A Rollercoaster Ride for Stadium Subsidies

Once O’Malley moved the Dodgers to Los Angeles, MLB owners became cognizant of a basic tenet in economics: the law of supply and demand.24 As long as there were more cities that wanted to capture the essence of professional sports than there were MLB teams available, existing team owners could levy heavy stadium demands on cities, which would often pay the price.25 By keeping a limited supply of professional baseball teams, the public share of new stadium financing by the end of the 1950s reached close to 100%.26

Shortly thereafter, MLB club owners learned the flip side of this rule, when, in November 1958, New York lawyer William Shea and former Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey announced plans to launch a rival professional baseball league, the Continental League.27 In fear that the planned rival league would begin to gain a presence for itself in untapped MLB markets, MLB owners quickly announced that they would expand into most of the territories that the Continental League sought to enter.28 From 1962 through 1969, MLB expanded from sixteen to twenty-four teams, temporarily returning the supply of baseball teams back into equilibrium with demand.29 As a result, the rate of stadium subsidies fell during the early part of the 1960s from nearly 100% to just above 60%.30

This counterbalance, however, was short-lived. On August 2, 1960, the Continental League ceased its plans to launch a rival league, and thereafter no other investor group seriously proposed doing the same.31 As a result, once the next wave of communities interested in investing in professional sports emerged, MLB clubs again had an opportunity to increase their subsidy demands.32

C. Stadium Subsidies Today

Since the 1970s, most local communities have paid between seventy percent and eighty percent of new stadium building costs.33 Today, these subsidies are paid to MLB teams, as well as to teams in the National Football League (“NFL”), National Basketball Association (“NBA”) and National Hockey League (“NHL”).34 Although the modern subsidy rate remains below that of the late 1950s, most teams exert more power over local communities today than ever before.35 This is seen in three ways.

First, local communities today are paying more than ever before to build sports facilities.36 For instance, the Astrodome, which was the most expensive sports facility built or refurbished prior to 1968, cost $35 million.37 By contrast, the Skydome, which opened in Toronto, Ontario in 1989, cost $532 million.38 In addition, the new publicly funded baseball stadium in Washington, D.C., which opened in April 2008, cost $611 million,39 and Indianapolis’s new football and NCAA basketball stadium, which opened in August 2008, cost $720 million.40 ….

In addition, the number of new facilities that sports teams are demanding is also rising.42 From 1950 to 1959, sports teams moved into only seven new sports facilities, as compared to twenty-one from 1960 to 1969, twenty-five from 1970 to 1979, fourteen from 1980 to 1989, thirty-two from 1990 to 1998, and already more than forty since 1999.43 A significant percentage of the increase in new stadiums built over the past decade is attributable to baseball and football teams, which once shared community stadiums, beginning to demand their own separate facilities.44 Another component of the increase is based on teams with greater frequency declaring their facilities obsolete.45 For example, in 2002, owners of the Spurs basketball team demanded that the city of San Antonio build them a new public arena, even though their current arena was just ten years old.46

Finally, in recent years, teams have even begun to negotiate the right to keep sports facilities’ non-sports related revenues.47 For instance, when the State of Maryland in 1998 built its new state-of-the art football stadium for the Baltimore Ravens, Maryland agreed to provide the Ravens’ ownership with rights to all of the stadium’s revenues, including those derived from rock concerts held during the NFL off-season.48 Similarly, in Miami-Dade County’s recent stadium agreement with Marlins ownership, the county agreed to provide the Marlins owners with 100% of all non-baseball related revenues, including revenues from rock concerts, other sporting events, and even the sale of the stadium’s naming rights.49

In sum, these three trends have created “such a confusion of interests [that] ordinary tax payers are now expected to subsidize the already immense wealth of … an indescribably small number of owners.”50 In other words, subsidized sports stadiums have gone from being an exception in the world of professional sports to something far closer to the rule.51

D. Today’s Sports Teams Do Not Need Subsidies to Turn a Profit

Despite the trend toward subsidizing professional sports stadiums, most professional team owners do not need government aid to profit.52 This is because, in addition to earning a high rate of return on the team’s resale,53 most team owners have recently learned to capitalize on two important stadium-related revenue streams: stadium naming rights and personal seat licenses.54

Stadium naming rights are the rights of corporations to place their name on major sports stadiums.55 Although the first reputed naming-rights agreement goes back to 1971, when Schaefer Brewing Company paid $150,000 to name the Patriots’ stadium Schaefer Field, sports teams did not begin to recognize the full power of selling naming rights until recently.56 In recent years, teams in large markets such as the New York Mets have sold stadium naming rights for as much as $400 million (20 year rights at $20 million per year).57 Meanwhile, teams that play in less traditional sports markets such as the Houston Texans have sold their stadium naming rights for as much as $300 million (30 year rights at $10 million per year).58 Although many teams that have obtained lucrative naming rights agreements have chosen to build expensive sports facilities, these kind of naming rights agreements could conceivably cover the entire cost of building a more affordable stadium or arena.59

Personal seat licenses (“PSLs”), meanwhile, are advance payments to purchase the right to secure a particular seat in a given venue.60 Although the Dallas Cowboys football team sold a limited number of “seat options” back in 1968,61 the NFL’s Carolina Panthers in 1993 became the first team to extensively use the concept of PSLs when they privately financed their new facility, Bank of America Stadium (formerly known as Ericsson Stadium).62 By selling PSLs before beginning stadium construction, Carolina Panthers ownership raised $180 million in upfront capital.63 Since then, several other sports teams including the Baltimore Ravens, St. Louis Rams, and Chicago Bears have copied this strategy, similarly raising substantial amounts of money.64

II. WHY AMERICAN COMMUNITIES SUBSIDIZE PROFESSIONAL SPORTS

Although professional sports teams rarely need subsidies to profit, most American communities continue to subsidize their professional sports teams because they fear their teams would otherwise move to other communities.65 As explained by sports economist Rodney Fort, “[l]eaving some viable locations without teams enhances the bargaining power of existing owners with their current host cities.”66 Some examples of viable locations without teams in each of the four premier sports leagues include: Los Angeles (no NFL team), Houston (no NHL team), Seattle (no NBA or NHL team), Cleveland (no NHL team), San Diego (no NBA or NHL team), St. Louis (no NBA team), Pittsburgh (no NBA team) and Baltimore (no NBA or NHL team).67

In a perfectly competitive market, new premier leagues such as Shea and Rickey’s Continental League would periodically emerge to meet communities’ demand for sports teams, and existing leagues would in turn have an incentive to expand into on-hold cities.68 However, in practice, the four premier sports leagues rarely face competition from any new league because sports markets have high barriers to entry.69 Indeed, competitor leagues are rarely able to compete against MLB or the NBA, NFL and NHL because these leagues enjoy an almost insurmountable lead in building a fan base, signing superstar players, acquiring television broadcast contracts,70 and obtaining playing facilities.71 For this reason, some liken a sports league’s tight control on its number of franchises to a form of blackmail or extortion.72

According to former Washington, D.C. mayor Sharon Pratt Kelly, the limited number of franchises in professional sports forces American communities to deal with “a prisoner’s dilemma of sorts.”73 The dilemma is that “if no mayor succumbs to the demands of a franchise shopping for a new home, then the team will stay where they are.”74 However, this outcome is unlikely because “if Mayor A is not willing to pay the price, Mayor B may think it is advantageous to open up the city’s wallet. Then to protect his or her interest, Mayor A often ends up paying the demanded price.”75

[Ed. Note: The author’s discussion on the propriety of subsidies and specific business and legal cases is omitted. Marc Edelman’s biography can be found on page 122.]

Notes

….

10. See Edelman, Bargaining Power, supra note 8, at 284 (describing the “glory era” of professional sports).

11. See id. at 284 (citing Lee Geige, Cheering for the Home Team: An Analysis of Public Funding of Professional Sports Stadia in Cincinnati, Ohio, 30 U. TOL. L. REV. 459, 461 (1999)); FORT, SPORTS ECONOMICS, supra note 7, at 338. Indeed, until 1950, there were just three publicly funded stadiums used by professional sports teams: the Los Angeles Coliseum (built in 1923), Chicago’s Soldier Field (built in 1929) and Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium (built in 1931). Edelman, Bargaining Power, supra note 8, at 285; see also John Siegfried & Andrew Zimbalist, The Economics of Sports Facilities and Their Communities, 14 J. ECON. PERSP. 95, 95–96 (2000).

12. See Edelman, Bargaining Power, supra note 8, at 285 (“With new metropolitan markets in the western United States opened by jet travel, the growth of in-home television, and the baby boomers coming of age, professional sports leagues for the first time encountered significant growth opportunities. Major League Baseball (‘MLB’), however, chose not to expand to meet these opportunities.”).

13. See Siegfried & Zimbalist, supra note 11, at 96; JAMES QUIRK & RODNEY FORT, HARD BALL: THE ABUSE OF POWER IN PRO TEAM SPORTS 15 (1999) [hereinafter QUIRK & FORT, HARD BALL].

14. See Siegfried & Zimbalist, supra note 11, at 96; QUIRK & FORT, HARD BALL, supra note 13, at 15; A Fan Site Dedicated to Preserving The Memory of Wisconsin’s Lost Treasure, http://www.milwaukeebraves.info (last visited Nov.12, 2008).

15. See JAMES EDWARD MILLER, THE BASEBALL BUSINESS: PURSUING PENNANTS AND PROFITS IN BALTIMORE 31–32 (1990); JEROLD J. DUQUETTE, REGULATING THE NATIONAL PASTIME: BASEBALL AND ANTITRUST 5, 8 (1999); see generally Marc Edelman, Can Antitrust Law Save the Minnesota Twins? Why Commissioner Selig’s Contraction Plan was Never a Sure Deal, 10 SPORTS L.J. 45, 47 (2003) (discussing the merger of the National and American leagues under the Major League Agreement).

16. See MILLER, supra note 15, at 31; JAMES QUIRK & RODNEY D. FORT, PAY DIRT: THE BUSINESS OF PROFESSIONAL TEAM SPORTS 480 (1992) [hereinafter QUIRK & FORT: PAY DIRT] (Table: Attendance Records: Baseball, National League).

17. See MILLER, supra note 15, at 31; QUIRK & FORT, PAY DIRT, supra note 16, at 480 (compiling attendance records for Major League Baseball’s National League).

18. See MILLER, supra note 15, at 79 and accompanying text; QUIRK & FORT, HARD BALL, supra note 13, at 15.

19. See MILLER, supra note 15, at 79; QUIRK & FORT, HARD BALL, supra note 13, at 15.

20. Id.

21. See JOANNA CAGAN & NEIL DEMAUSE, FIELD OF SCHEMES: HOW THE GREAT STADIUM SWINDLE TURNS PUBLIC MONEY INTO PRIVATE PROFIT 186 (1998); QUIRK & FORT, HARD BALL, supra note 13, at 16.

22. Hearings, supra note 9, at 55 (testimony of Sen. Charles E. Schumer of New York) (“I am one who believes in what Pete Hamill has written[,] that the three most evil men of the 20th century were Hitler, Stalin and Walter O’Malley, Sr.”).

23. See CAGAN & DEMAUSE, supra note 21, at 186; QUIRK & FORT, HARD BALL, supra note 13, at 16. Shortly after O’Malley moved the Dodgers to Los Angles, New York Giants owner Horace Stoneham followed by moving his Giants from Manhattan to San Francisco. The Giants’ move, however, was different from the one made by the Dodgers in that the Giants were struggling with attendance before heading to California. See MILLER, supra note 15, at 79–80; QUIRK & FORT, PAY DIRT, supra note 16, at 480.

24. See E. THOMAS SULLIVAN & JEFFREY L. HARRISON, UNDERSTANDING ANTITRUST AND ITS ECONOMIC IMPLICATIONS 112–22 (3d ed. 1998) (discussing the law of supply and demand).

25. See FORT, SPORTS ECONOMICS, supra note 7, at 140. At the same time, the law of supply and demand has allowed existing team owners to charge huge entry fees to prospective new entrants. See Fort, Direct Democracy, supra note 7, at 7 tbl.1.3 (showing rapidly increasing expansion franchise rights fees).

26. See Siegfried & Zimbalist, supra note 11, at 96; QUIRK & FORT, HARD BALL, supra note 13, at 19–20.

27. DUQUETTE, supra note 15, at 52–53; see also FORT, SPORTS ECONOMICS, supra note 7, at 134.

28. See DUQUETTE, supra note 15, at 53–54; QUIRK & FORT, PAY DIRT, supra note 16, at 479–87 (Major League Baseball added eight new teams in the years from 1962–69, with new teams beginning play in New York City, Houston, San Diego, Montreal, Los Angeles, Washington, Seattle and Kansas City); FORT, SPORTS ECONOMICS, supra note 7, at 134, 141 (“[E]xpansion and relocation also protect existing owners from outside competition.”); id. at 148 (discussing how leaving viable locations without teams increases the risk of new leagues forming).

29. See generally DUQUETTE, supra note 15.

30. Siegfried & Zimbalist, supra note 11, at 96.

31. See FORT, SPORTS ECONOMICS, supra note 7, at 134; see also Wikipedia, Continental League, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Continental_League (last visited Nov. 12, 2008).

32. See generally CAGAN & DEMAUSE, supra note 21, at 28–29 (“North America is in the midst of a remarkable stadium and sports arena building boom unlike any other in its history …. Between 1980 and 1990, U.S. cities spent some $750 million on building or renovating sports arenas and stadiums. The bill for the ’90s is expected to total anywhere between $8 billion and $11 billion, the bulk of it paid by taxpayers—and hidden subsidies could amount to billions more.”).

33. See, e.g., Michael Cunningham, Stadium Deal Just Doesn’t Make Sense: Money Could Be Used on Much More Important Priorities, SOUTH FLA. SUN SENTINEL, Feb. 22, 2008, at 1C (evaluating stadium subsidy percentages since 1992). Cunningham notes that: There are 20 baseball parks built or that are currently under construction since 1992, when Baltimore’s Oriole Park at Camden Yards sparked a building boom. The median public contribution for those parks was 73 percent of costs, according to information compiled by the National Sports Law Institute of Marquette University Law School. Id.; see also Siegfried & Zimbalist, supra note 11, at 96 tbl.1 (detailing Expenditures on New Sports Facilities for Professional Teams by Decade); FORT, SPORTS ECONOMICS, supra note 7, at 338 (finding, from the period of 2000–06, the median public contribution was just sixty-three percent. Yet, this figure is skewed downward because it includes the San Francisco Giants’ entirely privately financed stadium, built in the year 2000).

34. See Edelman, Bargaining Power, supra note 8, at 288.

35. See infra notes 36–49 and accompanying text.

36. See infra notes 37–41 and accompanying text.

37. See QUIRK & FORT, PAY DIRT, supra note 16, at 161–63.

38. See QUIRK & FORT, PAY DIRT, supra note 16, at 161–63.

39. See Eric Fisher, In D.C., Baseball Hits a Crossroads at New Park, STREET & SMITH’S SPORTS BUS. J., Mar. 10, 2008, at 18.

40. See Don Muret, Opening in 2008, STREET AND SMITH’S SPORTS BUS. J. (Jan. 21, 2008), at 15; Don Muret, Indy’s Showplace is also a Showroom, STREET AND SMITH’S SPORTS BUS. J. (Sept. 15, 2008), at 1 [hereinafter Muret, Indy’s Showplace].

….

42. See infra note 43 and accompanying text.

43. See Siegfried & Zimbalist, supra note 11, at 96; see also FORT, SPORTS ECONOMICS, supra note 7, at 340 tbl.10.1 (describing Recent and Upcoming Stadium and Arena Openings as of 2004). 44 See Editorial, Take Us Out, RICHMOND TIMES DISPATCH, Apr. 29, 2008, at A10 (“Orioles Park at Camden Yards started the trend away from multipurpose stadiums shaped like doughnuts and toward baseball-only stadiums with so-called throwback designs.”); see also David Armstrong, 49ers on the Move? Economics, Football-Only Stadiums Rarely Pay Off for Cities, Experts Say, SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE, Nov. 10, 2006, at B4; Bengals have Sold 20 Percent of Seat Licenses in Three Weeks, COLUMBUS DISPATCH (Ohio), Jan. 9, 1997, at 4D (discussing the city of Cincinnati’s building of separate ballparks for the Reds and Bengals); Hearings, supra note 9, at 14 (testimony of Sen. Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania) (“[Pennsylvania is] looking at four new [publicly funded] stadiums. Two are under construction now in western Pennsylvania for the Steelers and the Pirates, and two are in the immediate offering for the Phillies and the Eagles.”).

44. See Editorial, Take Us Out, RICHMOND TIMES DISPATCH, Apr. 29, 2008, at A10 (“Orioles Park at Camden Yards started the trend away from multipurpose stadiums shaped like doughnuts and toward baseball-only stadiums with so-called throwback designs.”); see also David Armstrong, 49ers on the Move? Economics, Football-Only Stadiums Rarely Pay Off for Cities, Experts Say, SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE, Nov. 10, 2006, at B4; Bengals Have Sold 20 Percent of Seat Licenses in Three Weeks, COLUMBUS DISPATCH (Ohio), Jan. 9, 1997, at 4D (discussing the city of Cincinnati’s building of separate ballparks for the Reds and Bengals); Hearings, supra note 9, at 14 (testimony of Sen. Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania) (“[Pennsylvania is] looking at four new [publicly funded] stadiums. Two are under construction now in western Pennsylvania for the Steelers and the Pirates, and two are in the immediate offering for the Phillies and the Eagles.”).

45. See, e.g., Siegfried & Zimbalist, supra note 11, at 96; David McLemore, Functioning in a New Arena; San Antonio’s Alamodome Alive despite SBC Center, DALLAS MORNING NEWS, Dec. 1, 2002, at 43A.

46. See McLemore, supra note 45.

47. See infra notes 48–49 and accompanying text.

48. Hearings, supra note 9, at 31 (testimony of Jean B. Cryor, former Member, Maryland House of Delegates).

49. See Benn, Rabin & Vasquez, supra note 5.

50. Hearings, supra note 9, at 13 (testimony of Thomas Finneran, former Speaker of the Massachusetts House of Representatives).

51. See supra notes 11–34 and accompanying text.

52. This argument is supported by building a mathematical model for sports team profitability, which estimates net operating income and annual expected return on investment by team. See generally QUIRK & FORT, HARD BALL, supra note 13, at 206, 212. The model considers the additional costs of constructing a new stadium and factors in revenue streams that are created by building a new stadium. See generally id.

53. See, e.g., FORT, SPORTS ECONOMICS, supra note 7, at 1–2 (showing that, since 1915, ownership of a sports team such as the New York Yankees has provided twice as large a rate of return as owning a diversified investment portfolio); id. at 9 (“Professional team sports generated revenues of about $13.9 billion in 2002–03.”).

54. See Zimmerman, infra note 79, and accompanying text.

55. See HOWARD & CROMPTON, supra note 3, at 272.

56. See id.

57. See Edelman, “Single Entity” Defense, supra note 3, at 914; see also Terry Lefton, CAA Hired to Land Sponsors for the Yankees, STREET & SMITH’S SPORTS BUS. J., Oct. 1, 2007, at 1; John Lombardo, Barclays-Nets: A Brand Grows in Brooklyn, STREET & SMITH’S SPORTS BUS. J., Jan. 22, 2007, at 1.

58. See HOWARD & CROMPTON, supra note 3, at 275 tbl.7–5 (compiling the largest sports venue naming rights agreements); see also FORT, SPORTS ECONOMICS, supra note 7, at 79 tbl. 3.8 (noting recent naming rights agreements). Among the newest stadium naming rights agreements, the Indiana Stadium and Convention Building Authority recently sold naming rights to their luxurious, new $720 million facility to Lucas Oil for $120 million over a 22 year period. See Muret, Indy’s Showplace, supra note 40, at 1. The Dallas Mavericks sold their naming rights for $195 million (30 years at $6.5 million per year), and the Atlanta Hawks and Thrashers sold naming rights for a combined $185 million (20 years at $9.3 million per year). See HOWARD & CROMPTON, supra note 3, at 275 tbl.7–5.

59. For one example of a more affordably built professional sports stadium, Miller Field in Milwaukee, Wisconsin was constructed in time for opening day of the 2001 season at a cost of just $313 million. See Edelman, Bargaining Power, supra note 8, at 288 (citing Don Walker, Auditors Blame ‘Enron-Style Accounting’ for Ballpark Cost Dispute; Stadium District Relied on Future Revenue, Memo Says, MILWAUKEE J. SENTINEL, May 22, 2002, at 1A). As another example, the San Francisco Giants privately financed their ballpark, which opened in 2000, for the total cost of $319 million. Id. at 289 (citing Richard Alm, Nosebleed Prices: Cost of a Day of Baseball Has Soared at New Arenas, DALLAS MORNING NEWS, Jul. 11, 2000, at 1D). Meanwhile, the Cincinnati Reds new ballpark, which opened in 2003, cost just $288 million to build. FORT, SPORTS ECONOMICS, supra note 7, at 340.

60. See Hearings, supra note 9, at 63 (statement of Jerry Richardson, Owner and Founder, Carolina Panthers); see also Hearings, supra note 9, at 104 (testimony of Paul Tagliabue, former Commissioner, National Football League); FORT, SPORTS ECONOMICS, supra note 7, at 42 (discussing the economics behind PSLs).

61. See HOWARD & CROMPTON, supra note 3, at 288.

62. Hearings, supra note 9, at 63 (statement of Jerry Richardson, Owner and Founder, Carolina Panthers); see also HOWARD & CROMPTON, supra note 3, at 288.

63. See Hearings, supra note 9, at 63 (statement of Jerry Richardson, Owner and Founder, Carolina Panthers).

64. See HOWARD & CROMPTON, supra note 3, at 288 tbl. 7–7 (compiling statistics on the size, price, and economic magnitude of current PSL programs).

65. See Fort, Direct Democracy, supra note 7, at 149–50; FORT, SPORTS ECONOMICS, supra note 7, at 140 (“Owners acting through their leagues limit the number of teams in their league by choice rather than through the forces of competition. There are two important indicators that the number of teams is smaller than a more economically competitive sports world would give to fans. First, rival leagues do form occasionally …. Second, every time a league announces that it plans to expand, a long line of candidate-owners forms in hope of becoming the newest addition to the league.”).

66. FORT, SPORTS ECONOMICS, supra note 7, at 141.

67. See LEEDS & VON ALLMEN, supra note 7, at 100 tbl.3.7 (listing the fifteen most populous metropolitan areas and their respective sports teams).

68. See generally DUQUETTE, supra note 15, at 52–53; FORT, SPORTS ECONOMICS, supra note 7, at 140.

69. See Edelman, Bargaining Power, supra note 8, at 291. Almost all attempts to form rival, premier professional sports leagues in the four major sports over the past forty years have failed. For example, in football, the World Football League emerged in the 1960s and almost from its first games exhibited dire financial trouble; missed payrolls were common and the league folded during its second season. See ROBERT BERRY ET AL., LABOR RELATIONS IN PROFESSIONAL SPORTS 93 (1986). The United States Football League then emerged in 1983 with a differentiated strategy of playing football during the spring; the USFL quickly found itself in a bidding war for players with the NFL, and in November of 1986, it too filed for bankruptcy. See id. at 95–96. In basketball, Harlem Globetrotters owner Abe Saperstein launched the American Basketball League in 1961, but the league folded in its second season. See id. at 155. Its successor, the American Basketball Association, which started in 1967–68, performed slightly better; however, it too was heading toward bankruptcy in 1976 when the league disbanded and four existing teams joined the NBA. Id. at 156–57. In hockey, the World Hockey Association was founded by entrepreneurs Gary Davidson and Dennis Murphy in 1972, but by 1979, most of its teams were bankrupt; the four remaining franchises were acquired by the NHL. Id. at 213–14.

70. See LEEDS & VON ALLMEN, supra note 7, at 124–25.

71. See QUIRK & FORT, HARD BALL, supra note 13, at 135.

72. See, e.g., id. at 6; Hearings, supra note 9, at 11 (testimony of Sen. Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania).

73. Fort, Direct Democracy, supra note 7, at 150.

74. Id.

75. Id.

THE NAME IS THE GAME IN FACILITY NAMING RIGHTS

Martin J. Greenberg and April R. Anderson

WHY THE BOOM?

The growth of naming rights deals did not occur in a vacuum; rather, they increased in tandem with the recent boom of new sports venues. The bottom line, of course, has been money. Corporate naming of stadia and arenas provides significant revenue for sports facilities and a positive attempt to defray public sector building costs.

It has really only been in the last decade when the use of corporate names for sports venues has gained widespread acceptance. The first corporate naming rights agreement was negotiated in 1973 between Rich Products Corporation and the County of Erie, New York, under which the new stadium for the NFL’s Buffalo Bills would be called Rich Stadium at a cost of $1.5 million over 25 years. Fourteen years later, in 1987, the contemporary use of corporate naming rights began in earnest when the naming rights to the Los Angeles Forum were purchased by Great Western Bank. Prior to 1990, only two of the NBA’s twenty-seven teams (7.4%) had sold naming rights…. [Ed. Note: As of June 2010, 25 of 30 NBA teams had sold naming rights to their playing facilities. Overall, 91 of 122 teams in the NBA, NFL, NHL, and MLB have sold naming rights to their facilities.]

Since that time, corporate naming rights for stadia and arenas have become the norm. This has occurred for two reasons. First, as more facilities take on corporate names, the public acceptance for such a practice has grown. Whatever initial reluctance there may have been toward what some experts have called the “corporatization” of stadia and arenas has largely dissipated to the point where naming rights deals are now status quo; an expectation that comes with obtaining a new facility.

Second, the increasing costs of building these facilities and the reluctance of public officials to raise taxes in order to fund them, make it necessary to maximize facility revenues. Thus, the selling of corporate naming rights creates an additional funding vehicle to recover, or reduce, initial sports facility costs and debt payments, which would otherwise be subsidized by taxpayers. As the trend toward building new facilities continues, so too will the use of naming rights, especially in light of the fact that if a new facility is to be built, it must carry with it some opportunity to pay for itself.

WHY CORPORATE AMERICA BUYS NAMING RIGHTS

A variety of corporations, representing a myriad of industries, purchase stadium naming rights. Airlines, automobile manufacturers, beverage producers, telecommunication companies, financial services, computer manufacturers, and consumer product producers all are currently represented by facilities bearing their names.