13

Streets

This section explains important concepts, terms and technical considerations that planners should be aware of when dealing with both the creation of new streets and alterations to existing ones. Traditionally the remit of engineers, the design of streets is a highly important area for planners to get involved in, as streets have a major impact on the usability and success of places.

While building and changing streets might not require express planning permission, such works are often part of planning applications, or plans to alter and build in town centres or other existing areas. Their design is – or should be – seen as more than technical decisions about manoeuvring and storing vehicles.

Streets are not the same as roads. Roads are mainly for transit; streets, which make up the vast majority of what is generally called the public highway, are about much more. The main problem with many streets is that they have been designed as though their chief purpose were the longitudinal movement of motor vehicles. Consequently they fail to achieve their full potential to serve buildings and their occupants, to enable people to move around on foot or by bicycle, and to be places simply to stay in and enjoy.

Designing streets should not be left to one professional discipline. Planners have a responsibility and remit to have a say in street design, and to help communities do the same.

Manual for Streets

Manual for Streets22 and Manual for Streets 223 are perhaps the best reference documents for planners wanting to understand the differences between streets and roads, how this relates to design, and the main technical matters. Sections 2.2–2.4 of Manual for Streets (pages 15–20) are an excellent place to start. Although Manual for Streets is no longer part of the government’s planning guidance lexicon, its basic principles are embraced within the NPPF and the PPG.

This excerpt from the PPG (Design, Paragraph 008) establishes an important consideration for street design:

‘Streets should be designed to be functional and accessible for all, to be safe and attractive public spaces, and not just respond to engineering considerations. They should reflect urban design qualities as well as traffic management considerations, and should be designed to accommodate and balance a locally appropriate mix of movement and place-based activities.’

Considering ‘place’ involves thinking about what people do (or should be able to do) in a street, what it is like to be in the street and the reasons why streets are destinations in themselves. Place should be as important an influence on design as movement (how and why people move through or within a street).

A balance needs to be struck between providing for movement and considering place in any particular street. Most types of street and road will have both movement and place functions, but for some, one function will be more strategically important than the other.

The trickiest streets to deal with, but also some of the most exciting and useful places, are those where large volumes of movement and busy place activities have to be accommodated in the same, often limited, space. These are often high streets and high roads, the centre for community and commercial activity which has grown up at the most accessible spot on the local movement network.

In any particular area, there are likely to be more streets of local importance in terms of both movement and place, such as residential streets that do not carry through traffic, and minor rural lanes. But these are unlikely to carry as much traffic as the smaller number of streets that are of strategic importance in terms of movement. This may, in part, be why highways and transportation professionals often seem more interested in streets that have an important movement function, while architects, urban designers and land-use planners tend to have more to say about streets with an important place function.

Figure 13.1

Streets can be functional and durable, and still look wonderful.

Streets must be designed with an understanding that they are complex, that their design must not relate simply to their role in carrying motor traffic, and that (most streets being contained by buildings) decisions will have to be made as to how finite street space is laid out and attributed to different uses. Planning needs to engage with such decisions, because they will have a direct impact on how well buildings, towns and cities work, and for whom.

How Decisions about Streets are Made

Planners are used to a quasi-judicial system where permission is deemed or expressly granted for building and land-use changes. However, streets are managed in a very different way. Because they involve public works to public land, the system assumes that their management will be undertaken for the public good by elected decision-makers. But beyond the publication of proposed traffic orders affecting how streets may legally be used (such as ones about new parking controls), there is very little in the way of a publicly scrutinised decision-making process for streets.

There is a massive amount of national highway design guidance and standards, covering aspects such as street signs, carriageway widths, tactile paving and surface markings. But although there is some relevant legislation, most of what we think of as hard-and-fast rules around street design are nothing of the sort. As long as local authorities have adequately researched, described and justified their approach, they can create a whole range of street conditions outside of national standard designs.

For example, Westminster City Council felt that guidance on the use of tactile paving at crossing points was not appropriate to its historic streets or the character of its areas. The council decided that instead of having large triangular areas of tactile paving where the back line was at 90 degrees to the angle of crossing (Figure 13.2.1), as specified in national guidance, it would use the ‘Westminster curve’ (Figure 13.2.2), keeping the depth of the tactile paving even across the whole crossing width. The blisters are in line with the direction of crossing but the back of the pad is curved, and is a consistent depth across its width. Some might argue that the visual contrast and depth of the tactile paving are not sufficient, but the curve reduces the amount used, which is helpful for people who find walking over tactile paving difficult. The council consulted widely on this change to the national guidance, explained its reasoning, and promised to monitor how the changed layout performed. The result was that the council was able to use its design, rather than the national one, as standard.

Figure 13.2.1

A conventional triangular tactile pad.

Safety audits and traffic modelling are also often seen as giving definitive answers, but they are just tools that can provide useful ideas and information. Rather like a design review, a safety audit sets out the view of someone not involved with a project about the way it is likely to work if built. It is up to those managing the project to consider that view and respond to the advice they are given.

A local authority might have its own streetscape guidance or standards. These can be very useful, as they allow for consistency in the materials used and help to keep maintenance costs down. But if you have a good reason to deal with a street in an area you are planning differently, you should be able to talk this through with the highways department.

Figure 13.2.2 A ‘Westminster curve’ tactile pad.

Because streets are publicly accessible, they have become the conduits for services, from gas pipes and sewers to 4G cables and water runoff drainage systems. This important function of streets puts added pressure on how street space can be configured and managed. The location of underground services and the need to access and maintain them often determines where street trees are planted, what type of surfacing is used, and where kerb lines and furniture are placed. For new streets, building in comprehensive servicing ducts can help with this.

Important Design Considerations

In 2009 the mayor of London published Better Streets as part of London’s Great Outdoors,24 a practical guide intended to help make real his vision of great city spaces. The document sets out six principles for better streets. These are as good a starting place as any when it comes to focusing the mind on the most important design considerations relating to streets, and not just in London. The following text is based on the content of Better Streets, and the principles have since been taken forward in other documents, including the mayor’s Transport Strategy.25 Information about schemes delivered using these principles can be found in Better Streets Delivered.26

Figure 13.3

With very little through traffic and much on-street buying and selling, this street has been designed to primarily support its market and those who use it on foot.

Understand function

A clear understanding of the function of a particular street and a brief that articulates this is one of the fundamentals of creating great streets. The improvements need to reflect whether the street is primarily a retail high street, a residential road, a place for cultural activity, a busy through route or something else. The more capable the street is of bearing heavy pedestrian use, the more appropriate the removal of segregation measures (such as guard rail to keep pedestrians out of the carriageway) is likely to be.

Imagine a blank canvas

It will not always be possible or even necessary to redesign an existing street from scratch. Many projects will involve taking what exists and seeking to improve it, and of course planners will be involved with the design of new streets from scratch. Whatever the situation, it is always worth imagining the space as a blank canvas, challenging each of its existing features as to whether it really needs to be preserved. Every feature that is added, remains or is replaced should be justified, and care should be taken to minimise the clutter of lighting, signage and materials.

Decide the degree of separation

Within the constraints of the street’s functions, physical segregation of road users should be avoided wherever possible, and only introduced where it is clearly essential for safety or other functional reasons. Recognise that people can act responsibly and can take reasonable risks. But this does not mean that every street user should necessarily be allowed to use all the space. Most streets work on the presumption that pedestrians can go everywhere, but motor vehicles can not; they need to stay in the carriageway, off the pavements.

Figure 13.4 Less is more in this simple crossing.

Reflect character

Most streets have a historic character of their own: Victorian, 1920s, post-war or perhaps boom-time yuppie. The design of the street should reflect that character, not through slavish pastiche, but through recognising that the street is the foreground to the buildings on it and that the buildings frame the street. A one-size-fits-all design-manual approach that produces the same outcome in all locations is unlikely to be appropriate.

Go for quality

Materials should be used in a consistent way, and should be of the highest quality and durability that can be afforded. The life of a public-realm project should be long. The choice of materials should therefore reflect the fact that high-quality materials often last much longer and are less expensive to maintain than cheaper, less durable alternatives. Good workmanship and attention to detail and finishes can make all the difference. For example, surface materials that have a natural variation in tone, like granite or porphyry, will not show marks as much as a single-tone surface.

Avoid overelaboration

A street is a stage or backdrop for human interaction; it should not compete with the activity it is intended to host.

Figure 13.5

A street in Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, Stratford, London.

Overelaborate design is rarely impressive in the long term. Great streets are created by the buildings and trees that frame them and the activities they contain. The purpose of street improvements is to complement the one and facilitate the other, not to make a loud statement. The quality of a public space depends not only on the street itself, but also on the design and the attributes of adjacent properties and frontages. For example, fortress-like security shutters on shopfronts can make a street seem unfriendly and hostile.

Think local

It is essential that traffic engineers and planners work together to ensure a comprehensive approach to developing high-quality public spaces. Better spaces can be created on a range of different spatial scales, from internationally significant projects such as Trafalgar Square at one end, to the improvement of a local parade of shops at the other. It is often the local schemes that will have the greatest impact on the quality of people’s lives. For example, simply adding a few bike stands and plants outside a station can help to bring to life what seems an unloved area.

Less is more

There can be a tendency to put stuff into streets, thinking that the more signs, lines and so on, the better. In fact, the opposite is true. Clean, simple and straightforward streets are easier for people to understand and use. They are cheaper to clean and maintain and are more flexible, adapting to whatever different uses and demands come along. Thoughtful designs only include elements that are absolutely necessary, using decluttering audits if changing an existing street. They then look at how the elements definitely needed can be merged, for example, by making a street lamp into a beacon at a zebra crossing instead of having two separate poles. The street should be thought of as the stage, not the star, with the focus being on its people, buildings, shops and plants as much as on the actual street design and formal street furniture.

Form follows function

As with buildings, streets should be designed for what they need to do. It is reasonable to erect robust crash barriers at the edge of a motorway, but the same barriers should not be used on a low-speed, pedestrian-dominated street.

A few things in Figure 13.5 could be questioned. The space (at Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, Stratford) appears to be overly engineered, designed for high traffic volumes rather than a new pedestrian- and cycle-friendly green quarter. For example, the cycle space is treated as a street in itself, with white lines and signs, which could encourage cyclists to go as fast as possible. It ends suddenly, with dead space left around it, in a way that is not helpful for cyclists or pedestrians, who are immediately expected to mix easily. There are crash barriers because the road goes over a canal, but they are not appropriate for this kind of pedestrian-priority, low-speed environment.

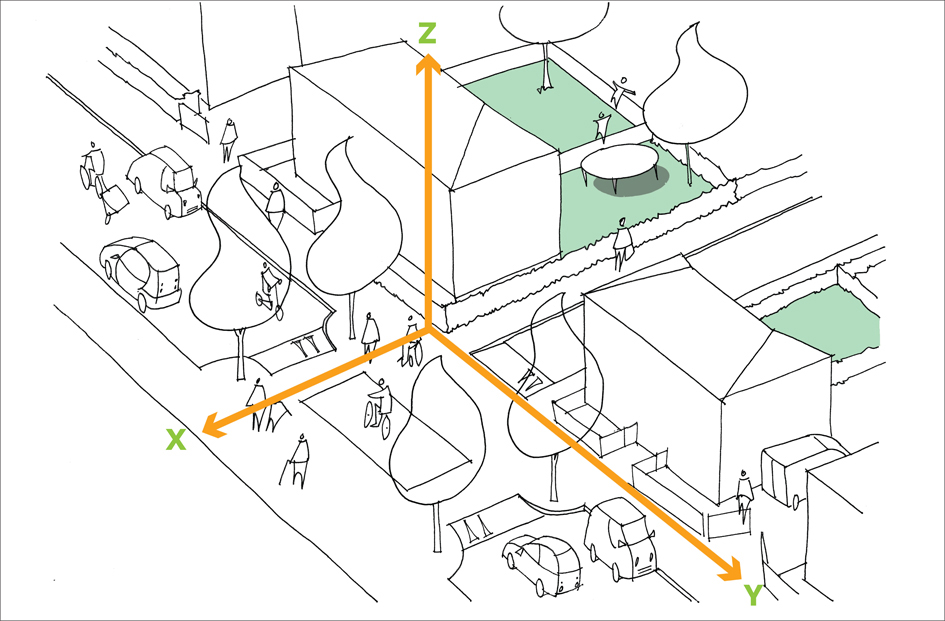

Figure 13.6

It is important to think of all four dimensions when designing a street: the X, Y and Z axes, and how people move through the space over time.

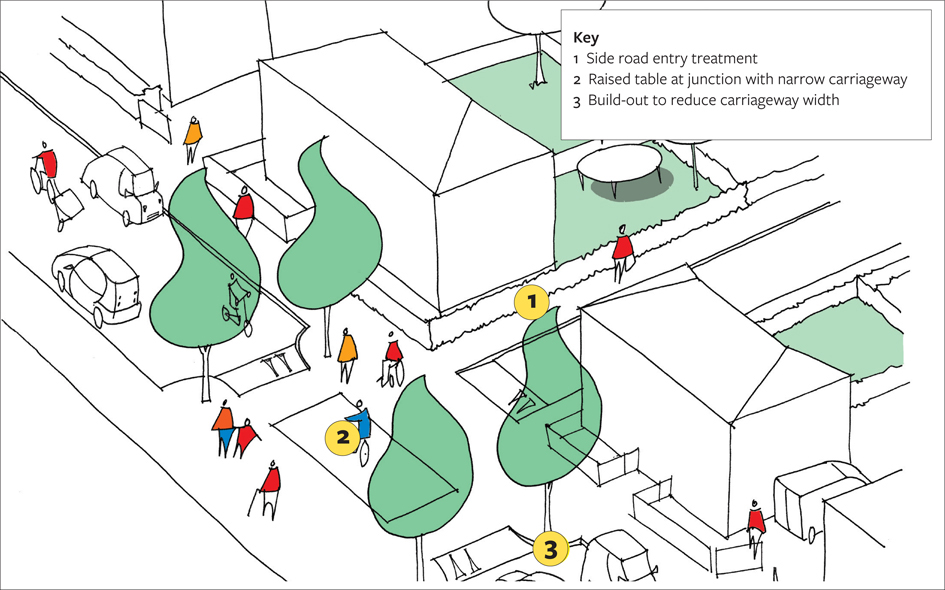

Figure 13.7 The main components of a street.

The XYZ of Street Design

Street designs are often presented in two dimensions, at a small scale, making it hard to imagine how the street will look and work in reality. Often layouts and details are lifted from manuals and guidance documents without thinking through how these would actually work on the site. This can lead to some unfortunate outcomes: confusing and disfiguring places that are of little use to anyone.

It can be useful to think of three axes to any street design: X across the street, Y down the street and Z up into the air and down below the surface. Combining this with thinking about how people use the street differently throughout the day, week and seasons will give a rounded, four-dimensional understanding of the street, as shown in Figure 13.6. This takes in both local and through movement, and considers how stationary or conduit features such as trees and pipes will be accommodated. Thinking about just one or two of these axes will not lead to the creation of good streets. Street schemes should be fully scrutinised, even though they are not formally checked by the public in the way that planning applications are.

Consider

- The best way to establish a design brief for a street is to talk to local people (including residents, businesses and politicians) about problems and aspirations. Do not be put off by the fact this might take professionals out of their comfort zone, and appear to cost more and take longer. Bad briefs lead to inappropriate designs, which are much more resource inefficient in the long term. Use tools like community street audits or Placecheck,27 and a framework like the Roads Task Force’s grid of what it calls ‘street families’.28

- If anyone says that a particular design idea will not work, ask them to be clear about why this is and from what perspective. Too many designs are talked down because they ‘won’t work’ for motor traffic (which often, in practice, means ‘isn’t ideal’ for motor traffic), but might get nodded through despite not working for pedestrians, cyclists, buses or other users – or the place as a whole.

- Challenge any highway engineer who says that there are absolute rules on important design parameters (such as lane widths and corner radiuses). Conventional practice is not the same thing as a rule.

- There is evidence that car parking in a town centre does not support the local economy as much as local businesses might think. Avoid taking sides in the ‘car is the devil’/‘car is king’ debate. Instead, think about a balance of provision to help the town centres you are working with. Use the available evidence to inform decisions, and, if this is not available, consider spending a modest sum on early surveys to establish the actual spend-by-mode-per-month pattern on the high street in question. Remember that car access is not the same as car storage. While for some people getting to a town centre by car might be important, it is not good to allow parking along a high street in a way in which parking manoeuvres make it a worse place for pedestrians, cyclists, shoppers and through traffic.

- Maintenance budgets are important in two ways. First, capital improvement schemes can piggyback on routine maintenance programmes, minimising total spend, adding value and minimising overall disruption. Second, the value of a new capital asset can be badly eroded if continuing maintenance is not provided for from the outset.

Figure 13.8 All the street furniture has been put in line in the ‘furniture zone’, leaving the pavement clear for people to walk along.

- Streets are usually the public highway, and even when they are privately owned no one has the right to park outside their front door. Similarly, it is not essential for refuse vehicles (or other service vehicles) to be able to access each front door. Residential amenity can be greatly enhanced by managing access and parking on an area basis.

- Space for parking is used much more efficiently if all spaces are unallocated, rather than allocated to individual users (such as residents).

The Language of Streets

Sometimes planners and highway engineers find it hard to communicate with each other because they are using their own professional languages. Terms that one person might be familiar with might not make much sense to another. A few important highway terms are explained here.

User hierarchy

This is a very important concept behind all our street design and management legislation, guidance and policy. The idea is that there is a natural power imbalance between different street users, from the strong, hard motor vehicle to the more vulnerable cyclist and most vulnerable pedestrian. At the same time, precious street space is used least efficiently by the private motor vehicle and most efficiently by pedestrians. The hierarchy idea reminds us that we should put pedestrians first, followed by cyclists, then public or shared transport users and, finally, the private motor vehicle.

Figure 13.9 Parking pads can be a good way of accommodating cars at certain times, without making the carriageways in a town centre excessively dominant.

Highway

The highway is the space that is designated as public highway and is normally controlled by the local authority. This is often all the space between buildings, but some streets have open forecourt areas in front of buildings. These might look like highway but could in fact be private (such areas are often marked out with metal studs). The highway can include many different elements: a few are shown in Figure 13.7.

Carriageway

The width of space given to motor vehicles. It might be one or more lanes wide, and might include both motor vehicle and cycle lanes. The width of lanes and the carriageway is important to the way the street works. In general, vehicle lanes should be 2–3 metres wide or over 4 metres wide. Lane widths of 3–4 metres can cause problems for cyclists as vehicles try to squeeze past them. The lanes and carriageway will not take up all the highway land in most streets. In places that need to accommodate a great deal of place activity, it might be appropriate for the carriageway to take around half of the overall width. However, often they take up around 80% of the width, pushing out non-through movement activities, which can be a problem in town centres in particular.

Figure 13.10

The apparent width of the carriageway has been reduced by using the lighter pavement and kerb colour in the drainage gully.

Pavements

These are the areas where pedestrians walk; where place activities happen; where services, trees, benches, bins and so on are placed; and the space that gives direct access to buildings. Pavements are therefore an important part of any street, and planners should check that there is enough space on the pavements for everything expected of them. The use of a furniture zone (as shown in Figure 13.8), which keeps all the objects near the kerb, leaves a walking zone free. The margin between the pavement and the carriageway is the kerb. This is normally a raised edge, allowing for gutters on its carriageway side. Some streets have flush kerb lines, often at crossings or around junctions where the carriageway is raised (a raised table). This can be controversial as people with site impairments can use raised kerb lines to navigate safely.

Junctions

These are the places where streets cross or merge, and where pedestrians might wish to cross the carriageway. These are the tricky bits of streets to design and manage. We tend to use traffic signals, roundabouts, box junctions and so on, and a variety of crossing types from zebras to pelicans and toucans.

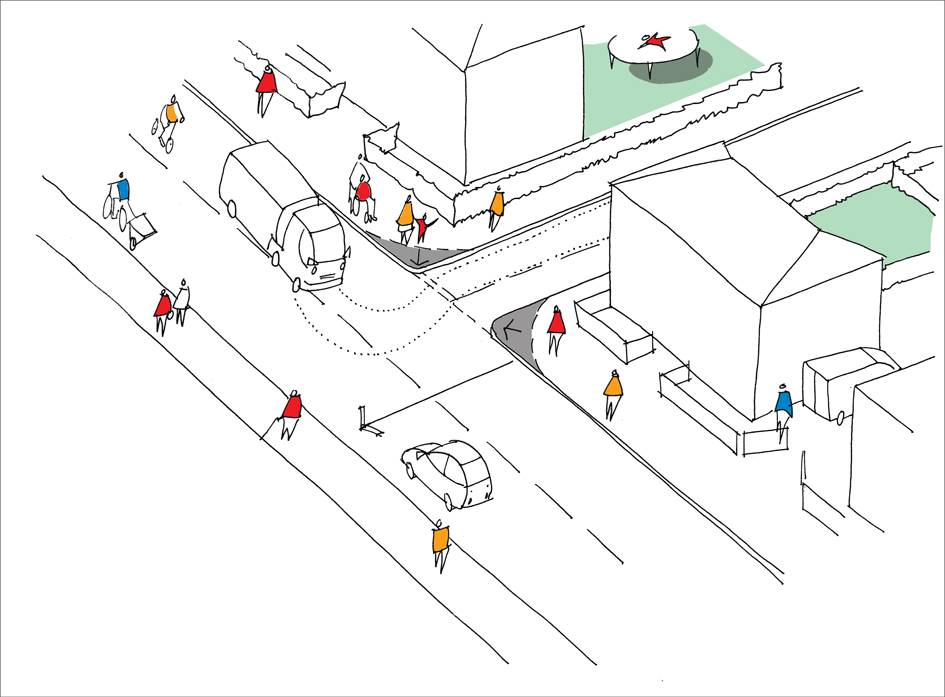

Sightlines and radiuses

Before Manual for Streets, national guidance called for wide corner radiuses (the curve of the kerb) at, for example, T-junctions. This was to allow drivers to see a long way down the road they were entering. However, later research showed that wide radiuses and sightlines encouraged drivers to go faster, and resulted in more accidents, so Manual for Streets promoted tighter turns and shorter lines of sight to make drivers more cautious. This has dramatically affected the amount of space needed at junctions and the crossing distances for pedestrians, allowing for more logical and efficient building layouts.

Traffic calming

Many housing layouts and town-centre masterplans attempt to use street design to keep traffic speeds low. Raised tables are often used to do this, sometimes going up and down seemingly at random across a new housing estate. If used with care these can work, particularly in areas with pedestrian crossings. But there are many other options too, including avoiding long, straight sections of road; using tree build-outs; and visually narrowing carriageway width with kerb-coloured gutter lines, as shown in Figure 13.10.

Figure 13.11 shows how the corners at T-junctions can be tightened to help slow speeds, following guidance given in Manual for Streets.29 Widely curving corners allow for the occasional large vehicle to turn without using space on the opposite side of the road. But, as explained above, they can make life more difficult for pedestrians and encourage faster driving speeds. The example shown is a type often used in a city-centre location with relatively low traffic levels. More information on designs to calm traffic can be found in Urban Design London’s (UDL’s) guidance note Slow Streets, available at www.urbandesignlondon.com

Figure 13.11

Tight corners: the dotted line shows how large vehicles have to use part of the oncoming lane when they turn, making them slow down.

Segregation, separation and shared space

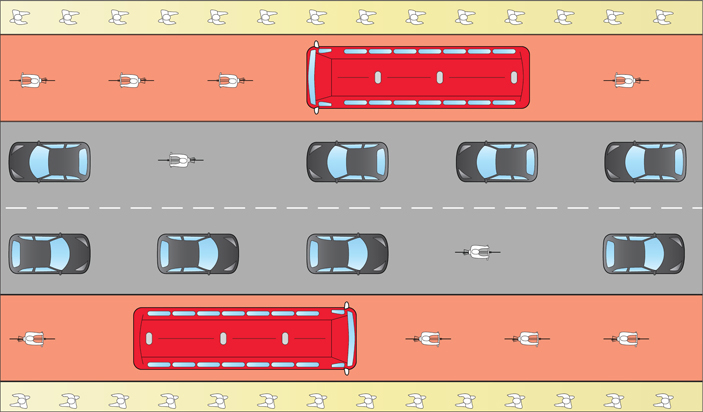

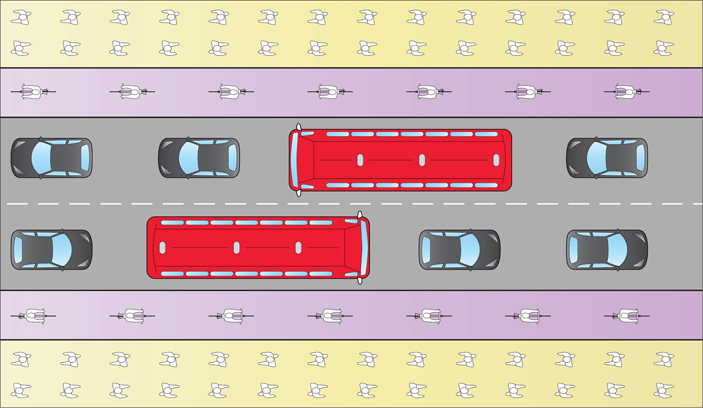

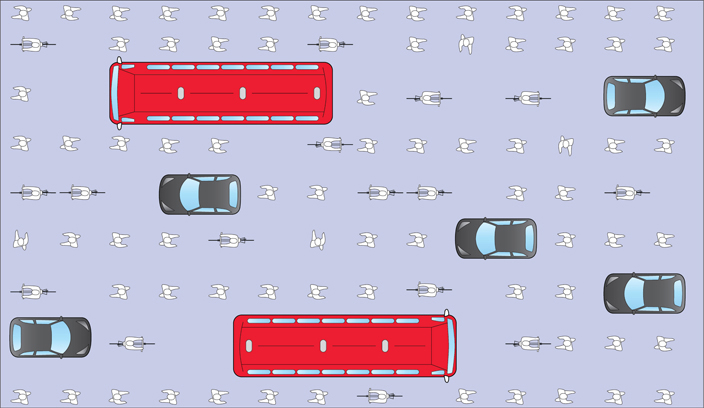

Questions of segregation, separation and shared space cause a great deal of confusion in street design. One option for a street is for all the space between buildings on the two sides of the street to be available to everyone (whether walking, cycling, riding a bus or driving), as shown in Figure 13.12.1. This unusual approach should only be used where there are large numbers of pedestrians and place-related activities, and motor vehicle use is seen as ancillary. It could be called fully shared space, as that is what people are doing.

In most streets, the different uses are restricted to distinct strips of space, and it is the amount of space allocated to each, and how they are detailed, that indicates how the space is being shared out. Figure 13.12.2 shows a traditional layout that allocates most of the space to motor vehicles and accommodates cycling alongside them. Here a separate lane has been created for buses, helping to shorten their journey times and improve the reliability of service. Crossing such streets is often difficult, particularly for pedestrians, for whom it is generally restricted to controlled crossings. This type of layout can work well for major through routes but is less appropriate for busy town centres.

Figure 13.12.3 shows an arrangement where more space is given to pedestrians and less to motor vehicles. Here pedestrians are encouraged to cross using the median strip (in the middle of the carriageway), and there is a safe area for pedestrians that vehicles cannot enter. This approach is often used for streets where a balance is needed between important place and movement functions.

The manner in which areas are demarcated either segregates people physically, so they cannot get into certain areas, or just separates them visually. The degree to which different users should be segregated, separated or mixed depends on the movement and place functions in the area. The more important the place activities are, the lower the vehicle numbers and speeds will be.

Level surfaces

There has been a fashion in recent years to have no height difference between pavements and carriageways. This might be across a whole junction, or down a length of a street. The idea is that drivers will not be sure what is going on and so will go more slowly, looking out for pedestrians and taking more care. The approach can work where there is very limited space and a large number of pedestrians. People on foot go anywhere they want and act as traffic-calming

Figure 13.12.1

A traditional layout with bus lanes shared with cyclists and narrow pavements.

Figure 13.12.2 A balanced street with vehicles separated from others, but more space and priority given to cyclists and pedestrians.

Figure 13.2.3 Fully shared, everyone can use all of the street.

measures in themselves. But this is a very unusual situation, and it can seem frightening for some people.

Most of the time a raised kerb, demarcating the pavement, will work better. It helps with drainage, provides a navigational tool for those with sight impairments and keeps drivers off the pavement area. Schemes such as those at Coventry and Poynton, often described as ‘shared space’ schemes, keep a level difference at the kerb line but use other techniques, such as carriageway colour and shape, to slow drivers,.

Figure 13.13 shows an approach in Coventry that uses geometric shapes and colour changes to influence driver behaviour at junctions. The design supports careful and considerate driving in a city-centre location with relatively low levels of traffic. More information on designs to calm traffic can be found in UDL’s guidance note Slow Streets.

Tactile paving

This is a national system of blister and other textured pavements that are intended to help those with sight impairments to use and cross streets safely. However, it is a highly misused area of national guidance, being hard to understand and often incorrectly specified. Blister paving is meant to indicate a crossing. The tail or stem leading away from the crossing point should come up to the building line or other route that will help users navigate and lead them to the crossing control box, while the alignment of the blisters at the crossing should help them cross in the right direction. The use of a different colour or tone from the surrounding pavement is intended to help those with some residual vision. Ladder and corduroy tactile strips are used to indicate the start and end of cycle lanes and pavements where cyclists and pedestrians mix.

Sometimes the use of tactile paving can seem counterintuitive. For example, Figure 13.14 shows tactile paving used in relation to a cycle route next to a pavement. The different tactile areas are meant to tell either cyclists or pedestrians that they are moving into, or out of, a space that they might need to share. Sometimes tactile paving is overused, marking very small areas and making its intended message difficult to understand.

When to Get Involved

Planners do not need to become highway engineers, but there are a number of ways in which they can improve the outcomes from their planning work by getting involved in street design. For example:

- Masterplanning, neighbourhood planning or policy writing on what streets in different places should be. This will influence how they are set out and managed.

- Pre-application and application stages for new development. Check dimensions and that streets can actually be built as set out, and will do what is required.

- At the planning condition stage for new development, set conditions for details but set some service levels to be met. Deal with these in the same way as for building design and landscaping.

- Oversee the adoptions of new-build streets. Make sure that the streets meet the original functions and specifications set out and agreed through the planning process. Remember that although a local authority might have its own standards relating to how it maintains streets, these are not legal requirements and they are often nothing to do with safety. They might be more about continuing existing working practices. The character, quality and detailing of streets in new developments will be very important

in determining how successful a place will be. Planners must be firm at the adoptions stage.

Figure 13.13 Colour and shape have been used in Coventry to define junctions.

- The same principles apply to changes to existing streets associated with town-centre area plans and estate regeneration plans. Although there will be less leeway for influencing the basic dimensions of the space between buildings, changes to streets can be an important way of delivering planning objectives, and creating the right atmosphere for regeneration to take hold and work well.

Points to Note

- Streets have two main roles. One is to enable people to move from one place to another. The other is to provide access to, and sometimes house, stationary or place-based activities such as shops or play space, that is, to be usable spaces in themselves. Different streets combine these roles to varying degrees.

Particularly difficult to design are those that have to accommodate a high level of through movement, while also providing high levels of local access and being pleasant places.

Figure 13.14 Overuse of tactile paving along a cycle route in a new housing development.

- The design and management of streets should reflect the roles they have to perform. Although a certain level of standardisation is needed to support road safety, streets should be designed creatively, responding to their context and uses.

- Any street has three spatial axes: its length, its width, and the height of the buildings that enclose it and any other three-dimensional elements. Time, a fourth dimension, will affect how the street is used, and options for its design and management.

- The street should be the stage, not the star. Clean, clear, practical and durable design approaches might be more appropriate than trying to make a dramatic visual statement through street design.