16

Town centres and transport interchanges

There are more than 3,200 town centres in the UK. They are places where we share ideas, buy goods and services, and travel to and from. They are usually places that we have in common with the different cultures and social groups that form our communities, and that help give identity to the neighbourhoods and towns they serve. A successful centre will be a loved and valued resource for many people: a place to meet and have fun in, as well as providing access to goods and services.

Large cities may have many town centres: London has 600 high streets and 40 major town centres. Each is unique, but some shared characteristics suggest how to influence their structure and design:

- Centres grow because they are at the centre of a catchment of people, particularly those within walking distance. As we saw in Chapter 2, this requires a rich network of streets with a natural core where streets and transport services meet.

- Centres are where people share access to facilities. Putting a library, shops, sports facilities or other amenities there will help to make them more convenient and viable.

- Centres support each other. One centre might develop a focus on, say, restaurants, and another on a certain type of shop. Both centres might also provide everyday services people can walk to, but they will have wider catchment areas for their specialist offers.

- Centres can be the focus of civic pride and social cohesion. Traditionally they have been the place to build expensive, impressive buildings, create parks and public spaces, and erect statues. The quality and character of these, and the importance shown to their care, can influence how people feel about their centre and their community.

- Centres must change to remain successful. The population being served may alter, and the way people access goods and services might change too. A centre needs to adapt accordingly.

- Centres include transport interchanges. This might be the meeting of bus routes, train stations and main roads. Interchanges bring people – potential customers – together, but careful planning is needed if conflicting activities are to work together.

The rest of this chapter looks at what these characteristics mean in terms of the design of centres, at a variety of spatial scales.

Catchments and Local Movement

The walkable neighbourhood

The walkable neighbourhood, anchored by an attractive and accessible town centre, is one of the most important spatial concepts in planning. The range of facilities and services available in a town centre means that people living within the walking catchment benefit from access to most of their day-to-day needs on foot, without depending on a car. And because town centres function as public transport hubs, residents are able to get to a wide range of destinations by public transport.

The size of the walkable neighbourhood is determined by how far people will regularly walk to reach the centre. This is likely to be 10–15 minutes, or a distance of 800 metres to 1.2km. It will vary between places, depending on topography, the street pattern, the attractiveness of the walking routes and the proximity of neighbouring centres.

The best way to identify the extent of the walkable neighbourhood is to begin by mapping the mixed-use, town-centre area, including the commercial, retail, leisure and other uses that make up the town centre. The walking catchment can then be plotted by following the street pattern outwards, taking into account the severance effects of railway lines or other features that restrict walking. Figure 16.2, reproduced from Sustainable Residential Quality,31 shows how this approach was applied to the area around a town centre as part of a study exploring how to unlock new opportunities for housing. In this case it can be seen that a substantial town-centre area and the permeable surrounding street network support a large walkable catchment area of around 420 hectares.

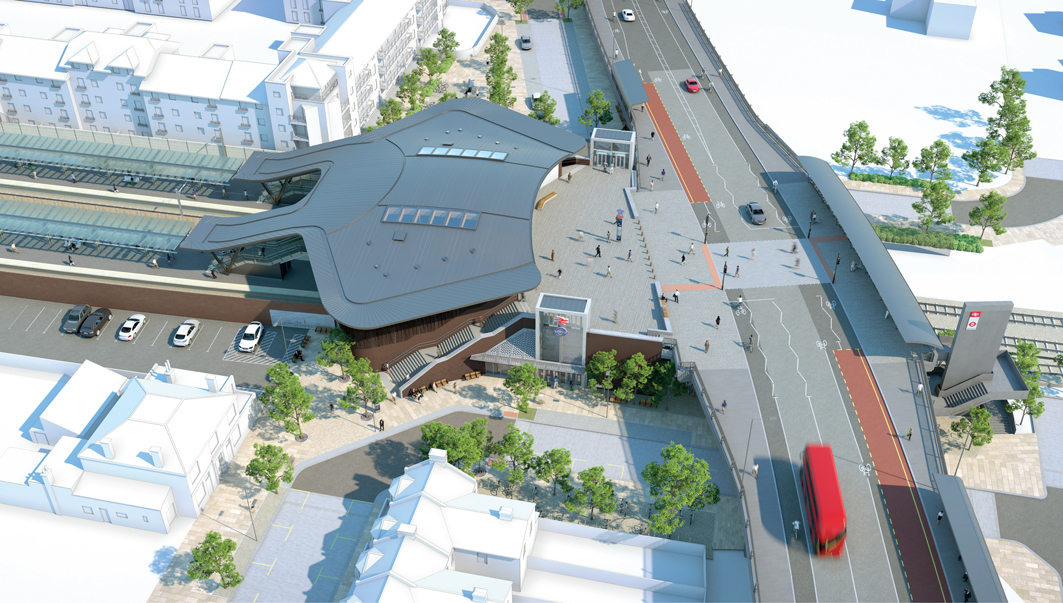

Figure 16.1

Improvements to routes and public space near a town-centre station can create a place that is easy to use and love.

Figure 16.2 A map showing the catchment area of a walkable neighbourhood.

A walkable neighbourhood can be enhanced in a number of ways. These might include identifying an opportunity for a new or improved walking route as part of a site redevelopment project, or providing a new bridge or crossing point to overcome the severance effect of a road, railway or canal. Such interventions could increase the size of the walkable neighbourhood. Or building more homes within the area, so increasing the number of people who can benefit from it. Other initiatives such as improvements to street lighting, the public realm and signage could strengthen the identity of the area and encourage more people to walk to their town centre.

Figure 16.3

Bus stands next to public space in Clapham Old Town, London.

Movement by vehicles

Public transport and cycling trips are also important, increasing the size of the catchment without needing to take valuable town-centre space for parking.

The design of a town centre and its surroundings can support cycling by providing safe, convenient and comfortable routes and adequate cycle parking. Routes might include sections segregated from motor vehicles, but great care is needed to ensure that the design does not create conflict between pedestrians and cyclists.

Buses should be catered for whenever possible with convenient bus stops or a bus station, close enough to destinations and other stops to allow for easy use. Good seating, shelter and lighting at the stops should ensure safety and comfort. Figure 16.3 shows bus stands in a lively town centre.

Private vehicles, vans and taxis

For many people, private vehicles and taxis will be the most convenient way of visiting the centre. The amount of parking that should be provided is controversial, with some studies showing the surprising amount of spending done by people who come to the centre by bus, foot or bike relative to those who drive.

Designing streets and junctions to encourage slow speeds through the centre, and ensuring that parking arrangements do not allow cars to dominate public space, can enable a workable compromise. An 80% occupancy rate for parking spaces is often given as an optimum. At rates higher than this, people will be driving around looking for a space; at lower rates, space will be given to parking that is rarely needed. Emerging parking systems could allow for spaces to be better used, reducing the overall number needed. For example, some systems have sensors in the road surface to tell if a car is parked in the space, and they relay the information to applications that drivers can use to help them find spaces quickly.

Similarly, deliveries can be managed in smart ways, ensuring that they take place at quiet times, using space that is given over to pedestrians or others for the rest of the day. Taxis have traditionally needed ranks but, again, mobile applications now allow people to hail services using their phones. This, and potential innovations such as shared hail-and-ride services, could blur the boundary between private and public transport, bring about changes to the ways in which people get to town centres, and free up space within them that is currently used by vehicles. All such innovations bring design challenges and opportunities.

Figures 16.4.1

Active uses can ‘wrap the box’, being placed around the outside of a large blank-walled building.

Figures 16.4.2 Large box buildings surrounded by car parks and ring roads can create poor quality areas, as shown in 16.4.1. But well designed infill development, as shown in 16.4.2 can help to overcome these problems, creating a better place and more value.

Figure 16.5

A walking loop helps ensure that shops in different parts of a town centre get customers (red lines are walking routes).

A number of town centres have reworked their streets in recent years to reflect changing approaches to the role of the motor vehicle in town centres, as explained more fully in Chapter 13.

Movement within the centre

Town-centre development in the second half of the 20th-century was dominated by the building of urban motorways and a proliferation of inward-looking shopping malls. This went together with out-of-town-centre retail development that focused primarily on the needs of the shopper travelling by car.

For town centres, interventions to improve private car access revolved around separating the moving car from the shopper, while making parking for the shopper as convenient as possible. This had a profound impact on the structure and character of many centres. Large malls and car parks tend to present long, blank walls to the areas around them, creating uninviting and at times unsafe places. One way of dealing with this is to ‘wrap the box’ (see Figure 16.4), locating active uses around the edge of the inward-looking building, and bringing life and interest to the surrounding areas.

The mall-with-car-park approach makes it easy to drive right up to, and park within, an indoor shopping area. This might suit the internal shops, but it discourages people from walking around other parts of the centre, depriving more traditional shopping streets of customers.

One approach to dealing with this is to develop shopping or leisure routes, or loops, as shown in Figure 16.5. Good wayfinding and lighting, attractive and comfortable paths, new or improved links and entrances to buildings or malls, and appropriate street crossings can all encourage people to visit more parts of a centre. In Figure 16.6, wayfinding signs and a bridge have helped to link attractions on both sides of the water.

A mix of activities

The best town centres have a wide variety of uses, including living, working, learning, buying, selling, exchanging, playing, observing, reflecting, creating, making, socialising and visiting. This can involve new and old buildings, as shown in Figure 16.7. Careful planning and design can ensure that different functions with competing needs coexist successfully.

Figure 16.6

Improvement to routes and public spaces helped increase footfall in Bristol’s harbour area.

In particular:

- Upper floors. In many high streets more use could be made of the upper floors of retail or business premises. Conversions of upper floors to residential use needs to be carried out with careful attention to access, safety and creating an appropriate mix of uses, especially in relation to the evening and night-time economy.

- Active ground-floor uses. The active management of the mix of uses in a town centre should be encouraged wherever possible, for example through a joint management company or property trust.

- Civic and community uses. Often local authorities actively contribute to a town centre’s decline by closing community facilities such as libraries.

- Live/work uses and co-working hubs may be alternative uses for retail premises, or empty offices (see Figure 16.8). Such spaces can help startup businesses and support the local economy.

- Low-value uses such as pound shops and charity shops can play an important part in a mixed economy. Aspirational design should not squeeze out the cheap and cheerful.

The close proximity of different uses in town centres can present challenges. For example, existing businesses may worry that new residents will complain about the noise and nuisance created by their established activities. Careful siting and design can help to alleviate conflict, for example by ensuring that bedrooms and main windows do not directly overlook service yards.

Figure 16.7 Shops, restaurants, a cinema and homes close to each other around high-quality public space in Walthamstow, London.

Spatial Planning and Town Centres

The geography of centres

Town centres and their walkable neighbourhoods are an important element of any area, whether local authority district or city. Some areas are monocentric, having a single centre, while others are polycentric, benefiting from a number of centres. Metropolitan areas such as London, Birmingham or Glasgow that grew rapidly outwards to incorporate existing towns and villages are polycentric, having multiple town centres. The geography of such places is defined by a network of distinct communities, each focused around a town centre and linked to other neighbouring centres by high-quality public transport. This pattern of town centres, the surrounding walking catchments and the high-quality transport links between centres, creates the basis for a successful urban structure. Hubs of interconnected centres, complementing each other, could help metropolitan suburbs to develop into more successful places.

The relationship between density and accessibility

Town centres and their walkable catchment areas lend themselves naturally to higher-density housing and mixed-use development with lower (and sometimes no) provision for off-street car parking, given the high level of pedestrian accessibility to facilities and public transport. More intensive forms of development are important in making the best use of well-connected sites. The increased population can help to support the viability and vitality of the town centre as a place to live and relax, as well as to work and shop.

Figure 16.8

Using buildings in new ways, such as flexible offices for startup businesses, can support local economies and make a town centre more lively.

This logic has led to the important planning concept of creating higher densities at more accessible locations. This makes the most of existing transport and service infrastructure; supports new services; and accommodates growth without relying on car-dependant and/or green belt development.

However, this brings design challenges, not least when no density ceiling is applied. This can produce hyper-dense neighbourhoods and excessively tall buildings, with some of the problems discussed in Chapter 15.

As well as access to transport services such as train stations and bus stops, the appropriate density in a town centre will relate to the following:

- The character of the area and the type of buildings that will successfully sit within it

- The carrying capacity of the area, including the ability for schools, health services and even pavements to accommodate more people

- Local movement opportunities, including whether main roads or rail lines sever local travel routes

- The displacement of businesses and communities, and the ability of the area to retain its identity

The Civic Centre

Setting the tone

As the hub of integration and activity, a town centre will play an important role in setting the tone for a local area and its communities. Historically, important civic buildings have been constructed in the centre, indicating the wealth and in some cases value systems of the dominant communities. Philanthropic acts focusing on central areas, for example providing water fountains, war memorials or town parks, may have helped to give character and identity to the centre (Figure 16.9).

Figure 16.10 shows an example of buildings that are harmonious neighbours and responsive to public needs, helping to make the centre feel that it belongs to the local community. Inward-looking or greedy buildings that detract from their surroundings and give little to the area will undermine any sense of civic pride.

Planning and design can make the most of a place’s distinctiveness: not just its physical heritage but also the valued evidence of its social history. Imaginative design can help to bring the past to life.

Human scale

Shopping centres with large blank walls, high floor-to-ceiling heights and domineering signage make many town centres less pleasant. But recent developments in the UK show that it is possible to use an alternative street-based approach to achieve commercial success. This relies on narrower shopfronts, more intimate signage, and avoiding the use of excessive floor-to-ceiling heights at ground level. Large-scale development can be integrated successfully with an established town centre if streets and outdoor public places are created at a human scale. The development does not need to take the form of excessively bulky buildings or to use large service yards.

The same goes for public spaces. Schemes that humanise town-centre roads, encouraging or even forcing lower driving speeds, and making both formal and informal crossing of streets easier, will help make an area feel more people friendly. Highway signs designed to be seen from a distance by drivers can overpower the intricate nature of

Figure 16.9

This striking church contributes to the area’s identity. Its yard is used for weekly food markets (though not on the day the photo was taken).

Figure 16.10 Clear, clean and inviting shops and building frontages can help town centres to thrive.

Figure 16.11 Public art in a public park.

streets, so they should be avoided wherever possible. Art can bring a sense of fun to spaces, too (Figure 16.11).

Figure 16.12

Boxpark Brixton, constructed out of shipping containers, is a popular attraction.

The Changing Centre

In recent years town centres have been affected by outof-town and internet shopping, and economic recession. In some areas there are high vacancy rates and low rates of investment. Many town centres suffer from traffic congestion and high pollution levels.

But there are also encouraging trends, indicating that people will always want to see, touch and hold the products they buy. It is widely accepted that shopping – regardless of whether actual buying takes place – serves important social and cultural functions. Many town centres are putting a great deal of effort into making a visit to them a stimulating and enjoyable experience. Increasing numbers of people of all ages are attracted to an urban lifestyle, and many town and city centres are becoming desirable places to live. Popup eating and party hubs (as seen in Figure 16.12) can bring life to an area.

Here are a few ways in which centres are changing:

- New forms of distribution, including click-and-collect and home delivery. These can reduce the amount of car parking required in town centres and the amount of space needed to service large shops

- The rise of local food shopping in outdoor markets

- Replacing enclosed, inward-looking development by new retail streets

These changes have been accompanied by the increased attractiveness of urban living and a move towards flexible workspaces catering for smaller enterprises (rather than offices with large floorplates in bulky buildings), which can be accommodated in many centres.

Figure 16.13

A station with distinctive character, like Kew Gardens station in London, can become a positive element for the local community.

Flexibility

Many town centres have benefited from the conversion of older buildings, such as the old town hall that became a library, then a nursery, then a gym. New town-centre buildings should be designed in the knowledge that lifestyles and technologies will continue to change. Flexible ground-floor accommodation is the key to successful town-centre design. New retail units should be capable of being combined or split up.

Transport Interchanges

The ease of getting to and from a town centre determines its attractiveness to regular and potential users (local residents, commuters who come to work every day, occasional shoppers and tourists), and commercial interests (including retailers, developers and new investors).

If treated well, stations can become community hubs; Figure 16.13 shows an example. Transport services (including buses, trains and taxis) and transport infrastructure (such as pavements, bus stops, stations, roads, cycle routes and car parking) are essential for good accessibility. But at the heart of a local transport system must be a location where transport interchanges can be made easily. This can be as simple as a bus stop outside a local station, or as complex as a bus, taxi and pedestrian interchange outside a busy mainline rail station in a city centre.

Figure 16.14

Easy-to-use and inviting station-side cycle parking.

In terms of investment and development, sites around an interchange (a railway station, for example), can be highly attractive to developers because of the accessibility of the location. Retailers are keen to benefit from the high pedestrian footfall associated with a transport interchange.

A town-centre interchange should offer convenience, comfort, safety and clarity to the user. That is, it should make using all transport modes simple and straightforward. This will require sufficient space for the numbers of people using it, clear signs, good sightlines and a logical layout. Access to all public areas should be step-free and obstacle-free as far as possible, and non-slip. Good lighting can help to ensure that people feel and remain safe.

The best interchanges are places of delight and help to create local identity. Excellent architecture and public-realm design can make a station and its surroundings more than just an important part of the centre, but a destination and landmark in their own right.

Meeting the needs of different users

An interchange might accommodate trains, buses, taxis, and cycle and car parking, and be near to main routes and housing, shops, restaurants and other non-transport activities. All will jostle for space and prime locations. The customer’s overall convenience is best served by locating the most space-efficient uses close to the centre, and the least space-efficient ones, such as car parks, further out. A bus stop or kiss-and-ride space can be a very efficient use of space, allowing many people to board and alight using the same space at different times. Taxi waiting areas use space less effectively. Their locations should reflect their relative importance.

The operational needs of different modes and uses should be carefully considered. Bus standings allow drivers to rest, eat or take a comfort break, and for the service to be regulated. Train sidings are a requirement of a good service. These might seem dead and unloved areas, but they help to make the system work. Bike parking should be visible (see Figure 16.14) and on a level with cycle routes. Fear of theft and difficulties of getting bikes to the parking area will deter cyclists.

Figure 16.15

The zone outside a station should be thought of as an extension to the station itself; a place for interchange.

The interchange zone

The interchange zone can include walking and cycle routes and public space. Interchange often takes place not in purpose-built facilities, but in locations where the facilities are more informal and controlled by different organisations. The idea of an interchange zone recognises the organisational challenges of bringing different facilities together (the highways authority may be the only organisation that can join up the different parts) and the importance of the wider area to the passenger’s experience of the transport interchange.

Consider

- Town centres need to be just that: a central area that can be reached by as large a catchment as practical, with ease and preferably without needing to use private cars. Try to manage the movement network around centres to improve the reach, comfort, attractiveness and convenience of walking, cycling and public transport access to them.

- Centres are hubs. They need a variety of uses and activities and a concentration of different things to attract people who may then use more than one service or facility. Try to manage land use and activities to ensure they stay vibrant and viable.

- As shopping habits change, the importance of the town-centre experience, and the quality of the environment providing this, increase in importance. Through traffic and parking should not dominate public spaces, or they will not feel like good spaces to stop in.

- Concepts such as walkable catchments, interchange hubs, shopping loops, consolidated servicing and time-sensitive access can all change the way in which a centre functions and feels. They can be useful when drawing up town-centre plans.

- We can think about three types of spaces we need, with the first being inside our homes, the second areas we share with neighbours, and the third where we are part of the wider community. Town centres are an ideal location for these third spaces, and they can be formal or informal, but everyone should be welcome and equal when using them.