17

Town extensions and large-scale schemes

Town extensions and large-scale development schemes are long-term projects. Figure 17.1 shows a typical town extension. They might take years, even decades, to build, providing new neighbourhoods that will be appreciated for generations. They come under different names; eco-towns, garden villages, new towns. They are likely to encompass design issues from across all the sections in this book, but four particular aspects make them special in design terms:

- The influence of time. Town extensions and large-scale development schemes will be designed and influenced by a variety of people over many years, so it is important to get the basic structure and design parameters right from the start, while allowing the scheme to flex as it develops.

- Knitting into the neighbourhood. In most cases a town extension or large-scale development scheme will have a significant influence on the area that surrounds or adjoins it, so it is important for it to tie into and complement its neighbours.

- Providing everything. A town extension or large-scale development scheme will have to provide new homes, workspaces, schools and other social facilities, and service infrastructure such as waste management systems and open space. This brings specific design opportunities and challenges.

- Designing at scale. Unlike most planning applications, a town extension or large-scale development scheme is likely to include whole new streets, parks and multiple buildings. It may also involve infill within an existing area such as a council housing estate.

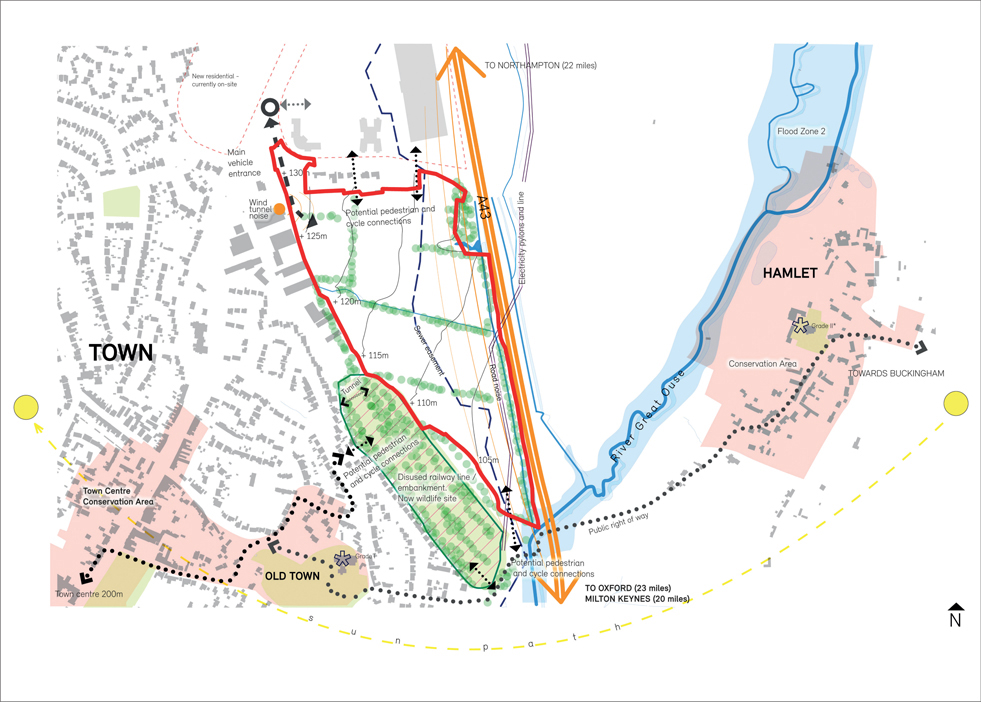

Most settlements and neighbourhoods develop organically over time. They are not really planned but evolve in response to changing lifestyles, economies, technologies, working practices and political priorities. That is not the case with major new housing-led schemes. The modern planning system, with its housing targets and allocation of housing land, does not lend itself to large-scale organic development. At the same time, designing a new neighbourhood or settlement as a whole often leads to very little in terms of delivery or quality. A balance is needed between making enough early decisions to provide certainty for landowners, investors and communities, without nailing down too many details and so stifling creativity and an iterative design process at a later stage. Major schemes are often developed through masterplans and design codes. The term ‘masterplan’ can be misleading: what is needed is a process that provides a route through which the scheme can evolve. A masterplan sets out the high-level structure for the site, focusing on issues such as how people will get in and out of it, the main routes through it, and the main landscape features. Masterplans generally parcel up the site into blocks that will be practical to develop one by one, and calculate the amount of development that is likely to be provided in these. This helps to ensure that the scheme can be phased and that it will be deliverable. Even though many masterplans are shown as three-dimensional drawings, illustrating the position, height, width and depth of buildings, it is rare for a scheme to be built in a way that closely matches the original masterplan. The graphical element of the masterplan is often a drawing based on an Ordnance Survey map. An example is shown in Figure 17.2. This will have been informed by site analysis and a constraints and opportunities plan.

Figure 17.1

Large-scale schemes bring unique opportunities and challenges. Masterplans are often accompanied by parameters and/or design codes. Parameters might set out specific requirements such as minimum and maximum building heights, depths and widths. Design codes can be more detailed, perhaps specifying street widths, landscaping requirements and facade detailing for different parts of the site. Figure 17.3 shows an example illustrating how smaller streets in the area should be detailed. It can be useful to think of these as the design brief for future work. As architects, planning consultants, developers and even landowners come and go, the masterplan, and associated design parameters and codes, will provide continuity. The masterplan, and other planning documents created at an early stage, should set out design principles for the site. These might relate to local requirements about such things as the efficient use of resources, how to respond to local character and context, or to specific quality standards for buildings. Figure 17.4 shows an example of how the edge of the development is to be treated. The principle in this case is to have a strong building edge up to and overlooking public space, and lakes that provide the buffer between the development and surrounding area. Well-conceived principles such as this will steer future design work, helping to hold the scheme to the ideals discussed with local communities and politicians. Most land in England is already in constructive use or subject to vested interests. Whether sites for large-scale development consist of farmland, social housing estates or former industrial land, they are likely to have, or have had, some kind of use, and will have occupiers, neighbours and others with a stake in them. This means that even if the development can be designed ‘from scratch’ physically, it must take into account its context and the views of those in the area.

Figure 17.2

An example of the analysis carried out in planning a town extension.

Figure 17.3 An example of a design code illustrating the character of a new mews street.

Figure 17.4

Principles such as how the edge of the development will be dealt with can be set early on.

Figure 17.5 A social housing estate being rebuilt incrementally. Original homes remain in use at back of picture, new homes have just be occupied to the left while the next phase is under construction to the right. Sometimes the demand for new housing is met by allocating areas of countryside for development. Generally these areas are on the edge of existing settlements, so the new community will be able to make use of existing services and facilities, but these sites can be remote and poorly connected, problems which the design should seek to overcome. In other cases redundant docks and buildings, end-of-life factories, former railway land and areas with low-value uses are given priority for development under policies favouring the development of brownfield sites. Many social housing estates have serious structural problems and buildings of poor quality, and some have unused and uncared-for empty space. Some have poor movement networks, and are isolated from neighbouring areas and facilities. They are sometimes redeveloped to provide more homes, which helps to fund improvements. This may involve total or partial demolition, or infilling new buildings alongside the old. Schemes that involve changing an existing estate need to be carefully phased and managed. Figure 17.5 shows how the old, new and future homes can work together within an area that continues to house people throughout the process. These major site allocation criteria are sensible in terms of planning, land use and service provision, but they bring

design problems with them. An urban edge or neglected estate will often be poorly connected with its surroundings, while available brownfield sites might be landlocked, separated from neighbouring communities by railways, motorways and waterways. One of the keys to successful large-scale design is to create effective new connections into surrounding neighbourhoods. It is a matter not just of connecting up streets, but of ensuring capacity, comfort and legibility of movement across the wider area by all modes. Figure 17.6 shows different types of movement opportunities to be provided in a scheme, from the most strategic routes that link the area to its surroundings (shown in red) to parkland paths (shown in dotted green). It is difficult to link the scheme into the surrounding area, but every opportunity has been taken, creating new through routes, and routes for walking and cycling. The wider movement network should go to and through the development area, linking to its surroundings by both primary and secondary routes. Having just one or two entrance roads can make the whole area into a large culde-sac, an inefficient structure that can create congestion bottlenecks and make the whole area feel dead for much of the time. It is often appropriate to accommodate through traffic in the site, taking pressure off surrounding areas and ensuring that the new neighbourhood can become a properly functioning part of the wider area.

Figure 17.6

The network of routes in a new development’. Walking, cycling and even, in some cases, bridle paths should connect into and though the site. Even if it feels

as though nobody will use such routes because there is nowhere to go, the design should be robust enough to work in 30 years or more, when both the site and its surroundings should have changed greatly in terms of land uses and activities.

Figure 17.7

Enough development is happening around the outskirts of Cambridge to pay for a new guided bus route, which in turn knits these new areas back into the city. Large schemes can bring with them enough funding and new users to justify and pay for improvements to existing rail and bus services, new tunnels and bridges or improved junctions. Figure 17.7 shows the view from a new guided bus serving an urban extension. Such improvements can benefit existing residents in the wider area, helping to counterbalance objections to any loss of green space or skyview, competition for local services and years of disruption. In these cases the masterplan will need to ensure that the development creates enough value to pay for the improvements. The changes also need to provide sufficient users to justify services. For example, it has been estimated that it requires a net residential density of at least 100 people per hectare to sustain a bus route. As well as ensuring that the movement network is well knitted into the surroundings, schemes should respond positively to their visual context. This might mean carrying forward certain building types, materials or details, but it could also involve ensuring that important views to and from surrounding areas are respected and enhanced. Being on an edge of a settlement or within an industrial area might present challenges, but it can also create opportunities for wonderful views, which will help to give the scheme character and distinctiveness. Such views can also help to orient people. For example, retaining a view of a church spire in the neighbouring settlement can help residents to feel part of the wider community. Finally, the site might include or sit next to some unattractive features, such as back-garden boundaries next to open spaces. Large schemes provide the opportunity to improve edges and remediate eyesores, helping not only the new scheme but also surrounding areas. Major schemes can provide a critical mass of people to support infrastructure such as shops and nurseries. They will need to do this if they are not to overload existing facilities in the area, and the new services should not be thought about separately from surrounding or adjacent communities. A masterplan might create a new service hub and ‘centre’ at the point most accessible to its new homes, but this might be better placed at the edge of the new

development, so that it can serve new and old residents together, helping to integrate the two parts. Care is needed to think creatively about how new and existing residents will move around and use the whole area.

Figure 17.8

An example of a co-housing scheme built specifically for older women. A major development should ensure a good mix of people within its community, and a variety of housing types will help in this. Figure 17.8 shows a range of homes, from small starter homes to large family houses and homes specifically designed with older people in mind. The mix can compensate for any lack of diversity in the surrounding area. A large-scale scheme will provide new open spaces. These can range from play streets (streets with low car use and low traffic-speed streets that children can enjoy being in) to large formal parks. The buildings and the spaces must work together. In general, buildings should enclose and frame spaces of all sizes, from green wedges pushing into the new area from the outside (as shown in Figure 17.9), to pocket parks scattered along main routes. The enclosure of large open spaces might create glimpsed views of buildings in the distance. The internal landscape structure of paths, planting and important trees will help to enclose and animate the open space (as seen in Figure 17.10). Whatever the type of space provided, it should be designed with its specific purpose and location in mind. Following are some pointers for designing and planning large-scale development: A place that is planned, rather than growing organically, can look contrived. This is particularly true if it is designed to have its own centre, closely surrounded by compact development and becoming increasingly loose towards a defined edge. Gradually decreasing density away from a hub generally works, but it depends on significant changes in accessibility. For example, some schemes might propose six-storey buildings next to the bus station, and three storeys just a couple of minutes’ walk down the road, but the difference in accessibility might not warrant such a significant change in form. Town extensions and large-scale development schemes involve creating a place or places with distinct character, or changing the character of an existing place. Some large schemes include many different character areas, each with its own name and perhaps its own palette of materials, but often all the areas are in essence much the same. There is

Figure 17.9

This new settlement includes different types of open space, from green wedges to pocket parks.

Figure 17.10 Using existing landscape elements, such as an avenue of trees, can help to make new schemes feel rooted and relevant.

some variety but the ‘characters’ are not really distinctive or authentic.

Figure 17.11

A street in a large urban extension that supports walking, cycling and structures. Some schemes have a variety of approaches to the appearance of elevations, which end up looking discordant. Using local building types, materials and types of detailing can help. A more successful approach can be to ensure that any visual variation reflects different types of occupant or use, and that the scheme will be able to adapt over time after it is built, allowing its character to evolve. Architectural detailing can help to form a development’s character, but the scheme’s basic structure may be more important in achieving this. For example, the tightness of street corners, the curve of the streets, how buildings turn corners and close views, how mature planting is used, and the presence or absence of parked cars will all affect the character of the place. One of the most challenging aspects of a large-scale development scheme is to ensure that it works well even before it is completed. The first residents and surrounding communities may have to live with building works, and an incomplete neighbourhood, for many years. Young families may spend whole childhoods living with a building site. Each phase should work well before the next is completed, and disruption should be kept to a minimum. Some building forms and layouts are easier to phase than others. Individual houses can be finished and used one by one, while a block of flats must be fully completed before any of the units can be occupied. With estate regeneration schemes, existing tenants may need to move out of their homes to allow a block to be demolished and a new one built for them to move into. This can be highly disruptive, damaging communities and causing upheaval for individuals. To minimise the amount of decanting, new homes might have to be built on open spaces or other open sites before anything is demolished. The design of both the layout and the buildings may be strongly influenced by the need to minimise decanting. The structure of a major development should be based on providing efficient and attractive ways for people to move around. The position and shape of the building blocks should follow this. The design should seek to minimise the need to use a car within the development: facilities such as parks and schools should be located so that as many people as possible will be within a ten-minute walk of them. Ideally bus stops should not be more than five minutes’ walk away.

Figure 17.12

People generally like to park close to their front doors. Front parking courts can allow for this. Some masterplans specify appropriate movement structures and set out design requirements for buildings, but fail to design the streets well. They may rely too much on heavy engineering solutions, seeking to separate modes and different types of journeys, creating a hierarchical system that appears to be dominated by traffic even if flows are low. A choice of routes provided by a rich and well-integrated web of streets, with crossroads and bisecting streets, is likely to work better. Where it is likely that the local authority will adopt the new highway, the authority’s requirements should be discussed at the masterplanning stage. For example, the masterplan should take into account the particular requirements of waste-collection vehicles, rather than leaving excessively wide junctions and turning heads to accommodate unknown requirements. The local highway authority’s management and maintenance needs, and the appropriateness of any standard requirements they are asking for (on carriageway widths and turning radiuses, for example) should be discussed, and challenged if necessary. Figure 17.11 shows a quiet street that is not visually dominated by the needs of the few motor vehicles that will use it. Instead it is designed so that drivers will feel that they are guests in the area, and act accordingly. Whatever level of car use is planned for must be carefully accommodated. Few issues are more important than parking: it must be designed so that parking blight (double parking and parking on pavements, for example) is avoided both within the site and in the surrounding areas. Standard street-design approaches, such as constructing a raised table at every junction, should be avoided. Every street element should be chosen because it is right for that particular location. Unallocated on-street parking (as shown in Figure 17.12) is often the most popular with residents, and it is generally less space-hungry than parking courts. Rear parking courts often do not work well, and they are not popular with residents unless they want to use their back doors as their main entrances. The urban design principle of keeping the public face and activity (such as arriving at a building) to the front, and the private face quietly at the back of buildings, tends to work. Consider

The Influence of Time

Knitting into the Neighbourhood

Finding space for major schemes

Connections and links

Providing Everything

Designing at Scale

Form and structure

Character

Phasing

Movement