15

Tall buildings

Planning can get very involved with defining ‘tall’ in terms of absolute height, number of floors, size relative to surrounding buildings, and so on. However, care should be taken not to become obsessed by height and forget about everything else. Generally planners want to understand and manage the impact of development, and they expect taller buildings to have a more intense and geographically wider impact than smaller buildings. This is why they set height or size thresholds, allowing certain policy requirements or assessments to kick in, and these help planners to manage the impact of tall buildings.

We can justify dealing with the design of tall buildings differently, and having separate policies for them, for the following reasons:

- The impact of a tall building might have a greater geographical spread than a smaller building because its shadow, microclimatic influence and/or human activity it generates will be greater than that created by a lower building in the same area.

- A tall building might be visible from further afield than a lower building on the site.

- Its size might raise particular technical or construction issues, relating to such things as lifts and structural wind-bracing requirements.

The first two of these assessments are driven by context. Impact is compared to the scheme’s neighbours or to something more similar to them built on the site. These aspects are not absolute in themselves, which is why planning policies often define ‘tall’ as being greater than the prevailing height in the neighbourhood, which varies from place to place. The third issue is about the performance of the building itself. These three reasons are not planning considerations in themselves, but they help to explain why tall buildings are often viewed differently from other types of development.

Height and Planning Policies

Planning policies for tall buildings generally aim to do two things. First, they can define areas that are, or are not, suitable for tall buildings. Second, they can set assessment criteria to use when considering individual tall building proposals.

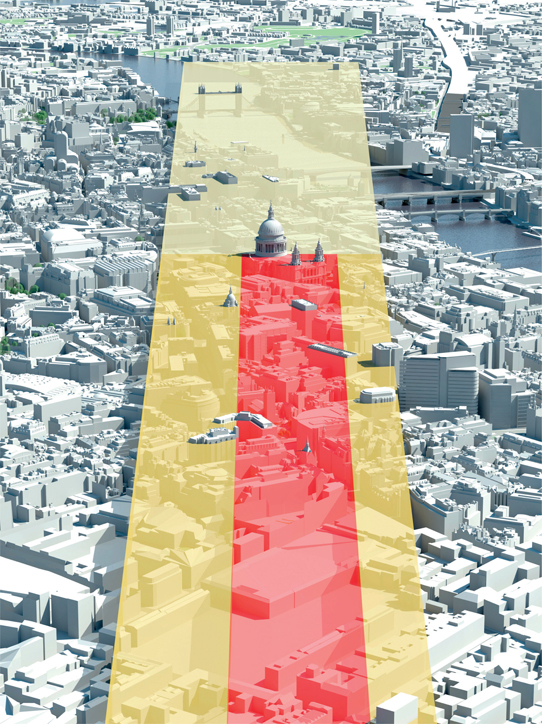

The first of these requires looking very closely at the existing character and condition of geographical areas and their potential to accommodate change. If an area’s valued character is likely to be damaged by buildings that are visible from afar, that generate a large number of trips, that need significant servicing, or that change the microclimate, the area might be designated as inappropriate for tall buildings. The criteria used to do this will vary from place to place. It might relate to visual intrusion into key viewing corridors, as seen in Figure 15.2.

Areas with capacity to accommodate growth in activity, for example because of good transport links or underused land, and which do not have a prevailing character that would be marred by taller structures, might be set out as areas suitable for tall buildings. For such an area, policies explaining the scale, use, design and functional requirements for such building are often included in area frameworks, masterplans and design briefs.

Assessment polices for tall building proposals should cover visual, management and functional issues. For example, the policies might specify that the top portion of a tall building, its silhouette and what it will look like at a distance from different directions will be considered, while these are not so important for smaller buildings. This is because the top of a tall building might not be visible from neighbouring sites, but it will affect longer views and the skyline.

Figure 15.1

Brent, London: a new residential tower, seen across a reservoir and nature reserve, replaces low-rise homes.

Figure 15.2 Viewing corridors set the parameters for assessing tall building proposals within strategically important views. Anything that sits in the airspace above the red plane will block the view and will normally be refused. Anything in the air above the yellow planes could affect the setting of St Paul’s Cathedral.

Figure 15.3

This tall building in Bristol has been reclad in an attempt to break up its visual bulk and add interest to the townscape.

Assessment policies might also refer to issues such as the impact on aviation (if near an airport), telecommunications (if signal shadow is seen as a problem) and how trips generated will be dealt with (both locally and for longer journeys).

Negotiating Tall Building Proposals

Architects and developers have their own priorities and processes, and at times they seem to be speaking a different language from planners. With tall buildings the architects may be working with a conceptual framework when designing the proposal. This helps them hold together the complex relationships between different design decisions, and test how changes to one element will affect others. The framework will link internal layout, servicing, building size and shape, interaction with surroundings, architectural expression and the physical structure. Asking for a change to one of these will require changes to others. These buildings are not simple to design.

It is the architect’s job to show how the scheme will meet planning requirements. If planners want to influence the design, it can be useful for them to consider how everything fits together rather than to focus on changing individual elements. Understanding the conceptual framework will help with this type of negotiation, and it can help build a good working relationship between the architect, developer and planner.

Planners might be wary of a proposal that does not have a clear and thorough conceptual framework, as the end result is unlikely to be a well-designed building. The planners might also wish to question some of the fundamental decisions behind the framework (which might stem from the client or a development brief), for example to construct an ‘iconic’ building where this is not appropriate. At times the planner can support the architect to influence the client.

In other instances the planner might feel that the client is not being adequately supported by an architect. Both these scenarios can be tricky for the planner, who cannot just tell the client ‘your architect is not good enough’ or ‘your brief is undeliverable’. Tact and informed comment are often the best way forward. Using a reputable design review panel can be helpful too.

Assessing a Scheme

As with all areas of planning, it is useful to have policies that set out what is expected and how proposals will be assessed. However, many planners are regularly faced with one-off, unexpected applications, not least for tall buildings.

Figure 15.4

Eagle House, London: The tower is integrated into a podium building which respects the local building line and provides active frontages.

In such cases the planner might fall back on national or local policies that call for good design. What does this mean for a tall building proposal?

Particular questions to consider might include:

- Will the building sit comfortably on the site?

- Will it be a good neighbour?

- Will it respect historic assets in the area, including their setting?

- Will it work well for those who will use it?

- Will it last, and be practical to manage and maintain?

A planning proposal might include a sweetener, such as the creation of public space or a viewing platform. It is worth asking if the scheme would be acceptable without this feature. No number of add-ons like this will overcome basic flaws in the design, shape, location or scale of the building. It is also worth asking if the feature being provided would not be needed in the area if the building were not to be constructed. If it would not be needed, the added feature cannot be said to be ‘giving something back’.

Figure 15.5 The base of 20 Fenchurch Street (‘The Walkie-Talkie’) in the City of London can get very windy, as the UDL team found out when they visited.

The following issues should form part of the assessment of any tall building proposal.

Quality of execution

The quality of execution, covering building materials, workmanship and detail, is particularly important with tall buildings as the buildings may be seen close up and from afar. The distance at which they will be viewed will influence the impact of detailing, materials and shape. A tall building will present challenges in terms of how it can be cleaned, repaired and reclad. Providing for these issues should be considered as part of the design quality.

Wind

Areas of low wind pressure are created immediately downwind of buildings. These low-pressure areas pull in air from higher-pressure areas, creating wind. If a low building is placed upwind of a tall one, the downward flow of wind is increased, causing accelerated winds near the corners of the tall building. At the same time, tall and wide building facades that are oriented towards the prevailing wind direction can increase wind speeds. A wind canyon effect can be created when air is funnelled between two buildings, causing intense wind acceleration. This effect is influenced by inappropriate height, spacing and orientation of buildings. More guidance on wind and microclimates is provided in Chapter 11.

Figure 15.6

The space around the Rockefeller Center in New York has a pleasant microclimate.

These problems can be addressed, but not always eradicated, by using features that deflect or break up downward flows of air at the base of windward facades. For example, the building shaft can be set back from the street edge, or a colonnade, landscaped flat-roofed area or canopies can be built on or next to the base element of the building.

Wind-driven rain can push moisture on to building facades, causing damage and making an unpleasant environment for people near the building. Wind can even blow rain sideways, making covered or partially enclosed spaces unpleasant. Air can create noise when it flows over elements attached to buildings or through gaps within buildings, and this can be particularly annoying when it is tonal and resonates with the natural frequency of the building elements. Care is needed to make sure that noise is not transferred through facades into buildings.

In areas of poor air quality it can be useful to consider whether tall buildings will trap pollutants in particular places, or whether the microclimatic effects of downdraughts will help to clean air at street level.

Sun, sky and shadow

Access to direct sunlight is a common planning consideration. Although the movement of the sun through the day and across the seasons is well understood and can be modelled, schemes often test out various massing and siting scenarios to minimise shadowing of open spaces in particular. Placing more floor space low down or moving the building shaft back from the open space can reduce the problem, as can increasing the width of streets or other open spaces where shadows are pronounced.

Skyview (the amount of sky seen from an open space) will be affected by the angle and position of building shafts, and how multiple tall buildings sit in relation to each other. Even if direct sunshine cannot be maintained to all open spaces, adequate skyview can make areas feel more pleasant.

Seeing into one building from another can cause problems. Changing shape or siting to reduce shadowing or increase skyview could push buildings together, so both issues should be considered together, where relevant.

Visual impact

A tall building will have an impact on the look, feel and character of both the local area and long-distance views, and the skyline. As can be seen in Figure 15.7, the same building can be seen from various distances, with all of the views being important.

Local impact will depend largely on how the bottom part of the building is designed and detailed, including the height of the base or podium, the materials used and the amount of human-scaled detail, such as windows. These will be seen close up and will influence how the building will fit in with others in the street.

The top part of a building may not be visible from close up, particularly if the shaft is set back behind a shoulder that might reflect prevailing heights along a street or block. If it is visible, it might influence the skyview, as described above. This and any shadowing impact will change the ambiance of the local area.

A top section that can hardly be seen from close up might be very prominent from afar. It will not necessarily be harmful just because it can be seen, but its relationship to other skyline elements and the setting of historic landmarks should be considered. It is important to understand how materials, shape and detailing will work at a distance – for example, how light will be reflected from the building. It can also be useful to think about the composition of views that will be affected. Are they panoramic (wide)? Or is there an important cone (narrow) view to a particular landmark, where the tall building could affect the focus if in front of the landmark, or alter its setting if seen to the side or behind?

Although a tall building should be designed holistically, its visual impact can usefully be considered in parts: as seen from the surrounding area; as seen from the middle distance (if there are open views); and as seen from afar. Drawings and models are likely to show the whole building. But it can be useful to consider whether the whole building will ever be seen in the way in which it has been presented, and if so from what distance.

Functional impact

One or more tall buildings in an area can change matters such as local activity patterns; the demand for local transport; and the type of shops and businesses that may be successful. When occupied, they will bring many more workers, residents or visitors to the area. These people will use local facilities, ranging from station exits and pavements to sandwich shops and doctors’ surgeries.

It is important to consider not only geographical access to facilities, but also their capacity to serve the new population. The design of a building should therefore be considered in the context of its functional hinterland. This will include the quality and size of pavements and spaces that those using the building will walk on, the capacity of transport facilities, emergency evacuation routes, and the position of services and how easy they are to use.

Flows of people from tall office buildings can be tidal, so spaces need to be large enough to cope with busy times, without feeling empty and forlorn during quiet periods. With residential towers, space must be provided for refuse collection, deliveries, gardening and other maintenance.

Figure 15.17.1

Figure 15.17.2

Figure 15.17.3 The same building proposal seen in different ways from different places. Top left, seen from close by. Top right, seen from far away. Bottom, seen from the neighbourhood.

Figure 15.8

Tall buildings can be in clusters or can stand alone. Here we can see the clusters in the City and at Canary Wharf in London and many individual tall buildings in between.

Figure 15.9 Poorly defined space at the base of a tall building can lead to problems such as crime (or fear of crime), and maintenance burdens.

Figures 15.10.1 and 15.10.2

The various parts of a tall building. Figure 15.10.1 shows all parts of the building. Figure 15.10.2 shows the ground floor, with the base of the building relating well to the street on which it sits, ensuring that a consistent pavement width is provided.

These uses should be practical for both residents and service operators, without dominating space meant for play or recreation.

Where a number of tall buildings are planned for an area, it is important that a well-tested masterplan ensures that the first few do not take all the hinterland capacity.

Technical information

The planner dealing with an application for a tall building does not have to be an expert in fluid dynamics for wind or the triangulation of viewing points. But in seeking to understand the proposal and weigh up the various issues, they should question the information provided with proposals and ask for benchmarking comparisons.

Assessing the Parts of a Tall Building

As discussed earlier, tall buildings are often viewed as a very particular type of development because of the different types of impact they can have, close to and from afar. These impacts relate to the different parts of a tall building, shown in Figure 15.10, and it can be helpful to consider each separately, as well as looking at the building as a whole. In the example shown, the top, or skypoint, has different brickwork and window treatment, helping the building look interesting and elegant from afar. The shaft is oriented to relate well to the orientation of a nearby circus with a historic obelisk at its centre, and to other buildings surrounding this. As can be seen in Figure 15.10.2, the ground floor of the tall building has been cut back so that the structure also relates well to the adjacent street and pavement, respecting the building line at this scale and retaining the full pavement width.

Figures 15.11.1 and 15.11.2

Sometimes a well-designed space can help you forget how tall the adjacent building is (15.11.1) – until you look up (15.11.2).

Podium

The podium or base of the building is the part that is seen and experienced from the street. It establishes the relationship between the building, its users and people at street level. Its design will have a significant impact on the integrity of the building, and the scale and definition of the street.

The podium should do the following:

- Give definition and support, at an appropriate scale, to adjacent streets and surrounding open spaces

- Contribute to human scale and comfort

- Promote active frontages to relate the building to its users and people passing by

- Integrate with adjacent buildings

- Minimise the impact of parking and service uses

Shaft/Middle

The shaft, extending from the base, constitutes the principal element of a tall building. It is the part that does the most to alter air movement patterns and determine how the building is perceived. It is the main money-making part of the structure.

The shaft should do the following:

- Be sensitively oriented on the site and in relation to the base of the building in order to minimise shadow, wind and the loss of views

- Include floorplate sizes and shapes that are appropriate for the site, context and use

Skypoint

The skypoint is the junction between the building and the sky. Seen from afar, it might have a significant impact on a city’s skyline.

The skypoint should do the following:

- Contribute positively to the character of the skyline, from different directions and distances

- Integrate rooftop mechanical systems into the design to create a well-conceived silhouette

Entrance and lobby

The entrance and lobby represent the building’s relationship with its neighbours and users. They can contribute to a lively, welcoming and attractive street experience. Even if the building is very large, the entrance and its surroundings should reinforce a fine grain of activity at street level.

Figure 15.12

The covered Sky Garden at 20 Fenchurch Street is open free of charge, though visitors have to book.

The entrance and lobby should do the following:

- Be outward looking; easy to see, find and use; and have clear sightlines if set back

- Be at grade and on the main public street frontage, offering views into the building at this level

- Be well detailed and architecturally designed, using lighting and landscape treatment to emphasise the main entrance, where appropriate

- Be free from domination by vehicular access or drop-off points

Servicing and parking areas

All buildings should be designed and programmed to accommodate front-of-house and back-of-house functions and activities. Back-of-house activities include refuse storage and collection, loading areas, ramps to internal parking, vents, meters and transformers.

For a tall building, which may have a small footprint relative to the amount of activity to service, this can mean the following:

- Screening these areas from public view and keeping them away from primary pedestrian areas

- Encouraging the sharing of service areas and activities within the building and, where possible, between buildings

- Consolidating and minimising the width of driveways and vehicular entrance and exit points into the building

- Providing vehicular drop-off areas at the side and rear of the site

- Accepting street-facing parking above ground only if it is wrapped by a practical, usable sized space for retail, residential or leisure activities

- Entrances and exits from basement parking should not create barriers at street level

- Underground building space should ensure the room, load capacity and soil depth for planting, so that at ground level these areas can integrate well with their surroundings

Skybridge or skywalk

A relatively unusual element, a skybridge or skywalk may link two buildings or an above-ground-level open space to a building, enabling occupants to move between them without having to travel to ground level.

A skybridge or skywalk should do the following:

- Encourage visitors to use facilities at higher levels

- Reduce the need for vertical transportation

- Avoid detracting from ground-level animation and activity

Sky garden or podium park

Some taller and larger structures provide open space within their envelopes, sometimes on top of a roof (see Figure 15.12), or above car parks or large retail space on ground floors. These can provide effective open space and a sense of relief from high-density development, without breaking the integrity of the built form.

A sky garden or podium park should do the following:

- Be truly public if that is the intention, without complex booking or entry arrangements

- Be visible and inviting, and linked to surrounding public routes and spaces

- Be protected from wind and driving rain at higher levels

- Avoid undermining the privacy of surrounding occupiers

Tall Building Uses

Planners should consider whether a proposed building is fit for its intended purpose, whether it will be capable of being converted in the future, and what ancillary services and facilities different uses might require. Here are some pointers to help with this.

Residential

One of the main differences between a residential and an office building is that the former will need greater subdivision of internal space into rooms. This, and the need for individual homes to have access to lifts in the building’s core, generally leads to narrower, thinner structures.

Residential buildings can also have lower floor-to-ceiling heights than office buildings, and require openable windows (albeit restrained) to allow for ventilation. They might also include balconies, although there is some debate about whether balconies are functional above 20 storeys.

Some features of tall residential buildings:

- Primarily concrete table-form frame construction

- External balconies for external amenity space and the use of views

- Statutory requirements stipulate openable windows to allow natural ventilation, which will have an impact on the building’s facade design and development

Office

Some features of tall office buildings:

- Larger floor-to-ceiling heights: generally 2.75 metres, and higher for trading floors

- The structure tends to be more visible, for example showing how it is dealing with larger spans

- Curtain-wall systems that are hung from each floor slab, and span from floor to floor, may provide opportunities to make the building elevations look distinctive

- External space is not visually dominant

- Occupation rates are greater, so entrances, plazas, vertical circulation and safety features have to work harder

Hotel

Some features of tall hotel buildings:

- Similar floor-to-ceiling heights as a residential development

Figure 15.13 A design for Chelsea Waterfront in London: tall residential buildings tend to be more slender than office buildings, as daylight needs to penetrate to the individual rooms.

- Similar facade technologies as office developments. Hotels tend to have no or few opening windows

- A deep podium to the base of the building. Ground and possibly first-floor retail offer. The recognised standard for retail floor-to-floor heights is 6 metres. This can make the ground floors seem out of scale with their surroundings, so care is needed to make sure whatever the internal ceiling height, the external facade looks human in scale and works well in the street scene.

- Ground-floor conferencing facilities use similar heights as retail

- Servicing requirements are significant due to the needs of facilities such as restaurants, shops, spas and swimming pools

- Generally no external balconies, although penthouses may have some integrated space

Tall Buildings and Heritage Issues

The reader may have expected this chapter to focus on the impact of tall buildings on historic buildings, conservation areas and their settings. It is true that in the past this has been the main issue in planning policies for tall buildings, and it is, of course, very important. But here we have focused on other, often overlooked planning issues to offer advice not provided elsewhere. More information on the relationship between tall buildings and the historic environment is provided by Historic England within their Good Practice Advice Note on Tall Buildings, Settings and Views.30

Consider

- Tall buildings are ones that are significantly higher than those around them, or that which they replace. As the prevailing height of an area varies from place to place, it is not possible to define what height constitutes ‘tall’ for a building.

- Instead of focusing on specific heights, it can be useful to think about how far the influence of a proposed building will spread; the taller it is, the wider area it may impact, and it is this impact that planners will want to understand and manage.

- Impact can be visual, on the setting of a listed building; it can be functional, by bringing lots more people to an area; or environmental, by creating shadowing or wind tunnels. All types of impact should be considered.

- Although tall buildings should be designed as a holistic structure, they may not be perceived as such once built. It is useful to consider the top, middle and bottom elements separately, as perceived from near, far and across the local neighbourhood.

- Tall residential buildings will have different characteristics to tall office buildings. It is useful for planners to consider how the structure relates to the use it will be put to.