2

The characteristics of well-designed places

As discussed in Chapter 1, certain characteristics are common to successful places, and achieving them will help to meet planning and political objectives. These characteristics relate to how we as humans use and experience places. Planning can help to retain them, or to create them.

To recap, the characteristics of successful places include:

- having a complementary mix of uses and activities.

- being fit for purpose, accommodating uses well.

- encouraging easy movement.

- including successful public space.

- being able to adapt to changing needs and circumstances.

- being efficient in how land and other resources are used.

- having an appearance that is appealing and appreciated.

- having a distinctive, positive identity and sense of place.

These eight characteristics should form the basis of the writing of planning policy and the consideration of any development proposal.

Set out below are some considerations (relating to each of the eight characteristics) that can help to create well-designed places that meet political objectives.

Mix of Uses and Activities

Uses – the activities, occupations, businesses or operations carried out in a building or on a tract of land – determine the life of the place.

A mix of uses may be appropriate at a variety of scales: within a village, town or city; within a neighbourhood or street; or even in a particular building. Figure 2.2 shows a variety of leisure-related uses sitting comfortably together.

Where a mix does not already exist, it can be introduced as a means of restructuring an area. In a town centre, for example, housing can be introduced to provide customers for shops, and activity when the shops are closed, as well as to occupy unused space above them. Figure 2.3 shows a hypothetical mix of uses within a town.

Different uses need to work together well, be in the right place and have users to support them. An audit of the facilities and services an area is lacking can be useful, informing policies and justifying development to provide the necessary floor space and customers. Uses should be located to complement current and future patterns of movement. For example, uses that rely on visitors need to be easy to reach, preferably by public transport. Those that depend on passing trade need to be on busy routes.

Space for the servicing of uses should be provided without jeopardising the appropriate liveliness or tranquillity of the place, considering both the immediate neighbours and the area as a whole.

Some uses rely on others to work properly. Chemists work near doctors’ surgeries, and nursery schools near homes, for example. Sometimes uses can successfully share a building, split across floors, or with different sides and entrances being used in different ways. Other uses work well together when they face each other across a street, where people can come and go between them with minimal disturbance.

Common issues for planners to consider include the noise, dust, smells or general disturbance that one use might create, and whether this will affect its neighbours. Designs that create buffers in terms of sound or sight (through orientation, structure, planting and changes in levels, for example) can avoid potential problems.

Figure 2.1

How an area is designed and fitted out can affect how we feel about it, and how we live our lives.

Some uses are seasonal, or the numbers of people visiting them might change over the course of a day or week. In such cases the challenge is to ensure that there is enough space for busy times, but that the place does not feel dead and unsafe at less busy times. Providing appropriate lighting or art, or pairing uses that have different busy times, can help. Temporary (pop-up) uses can be particularly helpful to animate a space during the downtimes, and test how well an activity might fit in an area.

Consider

- How different uses should relate to transport infrastructure and patterns of movement.

- How the different uses and activities will be serviced and supported by water supplies, sewerage, surface-water management, waste disposal, school places, doctors, hospitals, sports centres and other facilities.

- How the different uses will complement one another.

- How any potential conflicts between different uses can be managed or designed out.

- How the place can allow for changing uses and activities over a day, a week or a season.

What the NPPF Says

‘Aim to ensure that developments … optimise the potential of the site to accommodate development, create and sustain an appropriate mix of uses (including incorporation of green and other public space as part of developments) and support local facilities and transport networks.’ (Paragraph 58)

‘Good design … is indivisible from good planning, and should contribute positively to making places better for people.’ (Paragraph 56)

Being Fit for Purpose

A basic yet vital question to consider is how well a place works – for the people who live or work there, who use it or who pass by. For example, will homes be pleasant and convenient to live in? Do the internal arrangements make sense? Are the homes easily accessible from the street and surrounding area?

There might be generic requirements relating to planning or building regulations: matters such as floor-to-ceiling heights and delivery areas for shops, and noise privacy and internal storage space for homes. In such cases planners can use guidance or standards to ensure that a place will be fit for purpose.

Other uses, such as schools, medical centres and production facilities, will be more specialised. Here the design process should ensure that users’ needs are

Figure 2.2

The complementary uses within the buildings on New Road, Brighton, affect how people use the street.

Figure 2.3 Mixed uses in a town with more variety around the high street, the most accessible part of the area.

understood and options are discussed. A library, such as the one shown in Figure 2.4, needs to create a calm atmosphere, with space for private study and plenty of light.

Figure 2.4

Birmingham city library creates a good environment for reading and studying.

Consider

- How a development will meet the specific needs of its users.

- How easy it will be to maintain and manage.

- How easy it will be to service (with deliveries, for example).

What the NPPF Says

‘Aim to ensure that developments … will function well and add to the overall quality of the area, not just for the short term but over the lifetime of the development.’ (Paragraph 58)

‘Planning policies and decisions should address the connections between people and places and the integration of new development into the natural, built and historic environment.’ (Paragraph 61)

‘Aim to ensure that developments … establish a strong sense of place, using streetscapes and buildings to create attractive and comfortable places to live, work and visit.’ (Paragraph 58)

Movement

Movement – how people get around and how development is connected to the surrounding area – is a major influence on how a place works and what it feels like.

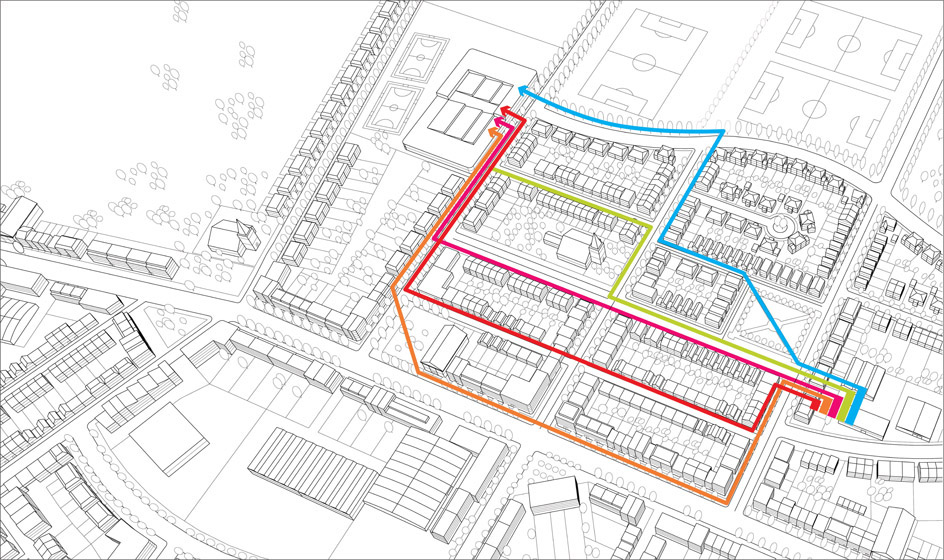

How buildings are designed and used, and where different uses go, should relate to opportunities to move around the area. Planners and designers need to understand the web of routes and the relative accessibility of different parts of the area, as shown in Figure 2.5.1. They need to know how the movement network can be adapted or improved to accommodate development. As seen in Figure 2.5.2, the structure of an area can encourage easy movement by giving people a choice of routes to the places they want to get to.

Movement needs to be considered at every scale. At the larger scale, this will include the connections that enable people to make relatively easy journeys to work.

At the more local scale, convenient movement will include routes that allow children to walk to school, and people to reach shops and parks easily. Paths can be framed by buildings, planting or street furniture. In Figure 2.6, large wooden seats mark the edge of the path and the neighbouring public space. In this case the path provides a cut-through, following a desire line and shortening the distance for pedestrians to get from shops to bus stops.

Streets are more than just traffic channels for vehicles: they are places for people. Well-designed streets encourage people to use them, and make being outside a safe and pleasant experience.

Figure 2.5.1

A movement network where cul-de-sacs are dominant can lead to longer journeys, in this case from home to school.

Figure 2.5.2 A well-connected movement network offers opportunities for different routes, enlivening an area. In this case a child walking to school can take different routes, passing friends, shops and so on.

Figure 2.6

A clear and inviting path next to a public space.

Figure 2.7 In this street an elderly cyclist decided to ride on the wrong side of the road; however, as the cars were being driven slowly and carefully through the shopping centre, they were able to stop to let him go first.

Successful places are easy to get into and move around, irrespective of any disability, or being laden with shopping or pushing a buggy. They feel safe, comfortable and convenient for everyone, and they have sufficient capacity for the pedestrians and vehicles that use them.

A place should be easy for people to understand and find their way around, or ‘legible’, as planners and urban designers call it (see Figure 2.8). Generally, a feature of something well designed is that it is easy for someone unfamiliar with it to sense how it works. For this reason, a place that is naturally legible will need little signage; features such as planting and buildings’ corners and roof details can help with orientation. If signage is required, it must be well conceived and effectively coordinated. Routes between places should be as short as possible – following the desire line, or the quickest and most direct way of getting from one place to another.

Comfort levels while moving around are influenced by a sense of crowding or isolation, both of which can cause problems. To control crowding, it is important to gauge the amount of space needed for the number of likely users. There are some tools to help with this, such as Transport for London’s Pedestrian Comfort Guidance.2 Discomfort can be caused by layouts that fail to create a sense of enclosure, by paths that do not respect desire lines, by dead-end routes that lead nowhere useful, or by poorly located routes that are far from any activity and are not overlooked.

Figure 2.8

An easily understood, legible route from crossing to shops.

National policy sets out a user hierarchy that should be followed in relation to movement. The design of development should support the most vulnerable users first, giving priority to pedestrians, then cyclists and public transport users – before, finally, motor vehicle users. What is appropriate will depend on the particular circumstances.

Consider

- How efficient, useful and easy it is to understand and use the movement network in the area.

- How well demands for movement and desire lines are catered for.

- The extent to which everyone is able to move around in the area, irrespective of their age or abilities.

- Whether car use dominates physically and visually, and in terms of the space it takes, or whether the user hierarchy for movement is supported.

- What opportunities there could be for development to improve connections in the area.

What the NPPF Says

‘Aim to ensure that developments … create safe and accessible environments where crime and disorder, and the fear of crime, do not undermine quality of life or community cohesion.’ (Paragraph 58)

‘Developments should be located and designed where practical to … accommodate the efficient delivery of goods and supplies; give priority to pedestrian and cycle movements, and have access to high-quality public transport facilities; create safe and secure layouts which minimise conflicts between traffic and cyclists or pedestrians, avoiding street clutter and where appropriate establishing home zones; [and] consider the needs of people with disabilities by all modes of transport.’ (Paragraph 35)

Public Space

Public space is the parts of a village, town or city that are available, without charge, for everyone to see, use and enjoy. Such space may be publicly or privately owned and can include streets, squares, arcades and parks. Figure 2.9 shows the types of spaces found in a typical town.

The success of any space depends on where it is and how it relates to surrounding buildings and uses, on the routes to and through it, and on its intrinsic design and how it is managed. It will also depend on the arrangement and design of its planting, paving, lighting, orientation, shelter, signage and street furniture, and how well these are managed and maintained. How these are approached should depend on the role of the space, such as whether it is somewhere to pass through, or somewhere to stop and enjoy. Figure 2.10 shows a new public space created from what was a coach park at St Paul’s Cathedral in London. The space, which used to be ugly and inaccessible to passers-by, is now of more value to a larger number of people. This photo was taken early in the day: by lunchtime the space is packed. The space has been designed to make the most of its relationship to the cathedral and to the pedestrian routes through it. Its management regime reflects its intensive use.

Figure 2.9

A neighbourhood should have different kinds of clearly defined open space.

Figure 2.10 A successful public space created from a former coach park at St Paul’s Cathedral, London.

Urban spaces are generally enclosed by buildings, other structures (including fences, walls and other boundary treatments), streets or planting. The relationship between the space and the elements that enclose it will influence its identity and success. A space surrounded by a metal fence with just one entrance is likely to be much less enticing than one surrounded by buildings with windows and doors, and paths leading to it. Similarly, a space heavily overshadowed by buildings is likely to be less comfortable to use than one where the sun can penetrate. Figure 2.11 shows how a new development can successfully create spaces by enclosing and animating them.

Buildings overlooking space can create a sense of safety and security, or a sense of intrusion. In some cases the internal use can spill over into the space, as with outside seating for a restaurant or a play area for a community centre. In other cases doors and openable windows can create a good relationship between people inside and outside a building. Planners and designers often use the term ‘active frontages’ to describe a positive relationship between a building and the space it abuts. But sometimes all is not as it seems. Figure 2.12 shows a fake ‘active frontage’, where the ground floor of the housing block is actually a car park, but fake windows and doors have been added to make it look, at first glance, like flats. Although this might be more attractive than blank walls, there is no activity to animate and oversee the street.

Figures 2.11.1 and 2.11.2

The plan and the corresponding computer-generated image show how the new blocks are intended to frame and enclose the street and the public space.

Consider

- How an area’s spaces contribute to its identity.

- The types of spaces, and how buildings help to frame, enclose, oversee and activate streets and public spaces.

- Whether the proportions of spaces and buildings create a pleasing and comfortable place.

- The effect of buildings on a space’s microclimate.

- Whether public spaces are located at centres of activity and through routes.

- How well the spaces will be landscaped through planting, surfacing and furnishing, and how well they will be maintained.

- How local distinctiveness can be retained where historic boundaries, building lines and plot sizes are significant.

What the NPPF Says

‘It is important to plan positively for the achievement of high quality and inclusive design for all development, including individual buildings, public and private spaces and wider area development schemes.’ (Paragraph 57)

Figure 2.12

Fake windows and doors create the look of an active frontage, without the overlooking and activity that would enliven the space.

The Ability to Adapt

Adaptable buildings and places are able to accommodate new uses, and changing demands and circumstances. They are capable of having a long life without inconvenient or expensive renovations.

The one thing we know for certain about any place is that it will change. However, we do not know much about how people will live, work, shop and use their leisure time in 10, 20 or 30 years’ time. We certainly do not know how the climate will change. Places change unpredictably in response to social, economic, environmental and technical developments, about which planners and designers often know little more than anyone else. Therefore, successful places flourish under changing conditions by being adaptable. Their buildings may change from houses to shops, to offices, and back again. Not all elements in a place have to change at the same time; however, the structure of the area should make it adaptable.

Places need to be adaptable at every scale, even down to the humble phone box (see Figure 2.13). A household makes different demands on the home as children are born and grow up, as people change to working from home, and as space is demanded by the latest home-working and leisure technologies. Towns and cities as a whole have to adapt as industries rise and decline, as demand for housing and the nature of workplaces changes, and as buildings and infrastructure age.

Figure 2.13 Phone boxes have been cleverly adapted to become a coffee shop.

The layout of streets and spaces will play a major part in determining how adaptable a place is. For example, connected streets (which anyone can pass through on their way to somewhere else) are more likely to be adaptable than cul-de-sacs. Most streets survive longer than the buildings in them. Being in public ownership yet bordered by multiple sites in private ownership, the positions and dimensions of streets are difficult to change. With new streets and new development likely, future adaptation should be allowed for. Where places prove not to be adaptable, the process of change is likely to be unnecessarily painful, expensive and wasteful.

Resilience, an aspect of adaptability, is the ability to recover quickly or easily from adverse situations. Such situations can include economic change, flooding, natural disaster, infrastructure failure, civil disturbance or terrorism. A range of challenges may be consequences of climate change.

To make a place resilient we need to know about its vulnerabilities and assets. A resilient place will have a degree of built-in redundancy in its systems, which means that if one part of the system is under pressure, another will be able to share the load. We need to be able to mitigate (diminish impacts) and adapt (respond to change). For example, parkland can be designed to flood, holding back water that would otherwise damage property downstream.

Figure 2.14

A useless piece of leftover space.

Consider

- How a place can be made adaptable by planning a movement network, with street width and block sizes that can accommodate very different forms of development in future.

- How the place will adapt to changing working practices and demands in office and industrial buildings, and changing living and homeworking circumstances.

- Whether there is potential to make changes such as subdividing space, dividing and adding entrances and servicing, putting in or taking out stairs and lifts, and changing servicing requirements.

- How the place’s identity has been shaped by its ability to adapt in the past.

What the NPPF Says

‘Planning should … encourage the reuse of existing resources, including conversion of existing buildings …’ (Paragraph 17)

Figure 2.15 What could be seen as simply a derelict building has been put to use as a scrapyard.

Efficiency

At a time when facing up to climate change should be a priority, the efficient use of resources (including space, energy, materials and water) is an essential element of design quality. Irrespective of climate change, well-designed places are efficient. They do not waste land, water or energy, or create unnecessary requirements for people to travel.

Well-conceived structures and building layouts are important in creating efficient places. Too often standard building and street forms are used, which do not fit together well on the site. As with using a biscuit cutter, odd shapes are left over that are too small to use properly, but are large enough to be wasteful and hard to manage (see Figure 2.14).

Efficient places make good use of what they have, even if that use is temporary. Figure 2.15 shows how a redundant building is being used by a scrap-metal business. Even if the business will have to move to allow the building to be repaired or replaced in future, good use is being made of it in the meantime.

Another form of inefficiency is putting people, and the places they want to get to, a long way from each other. Suburban sprawl is a classic example of this, encouraging car use and resulting in commuting lifestyles for many. By contrast, the compact-city approach focuses on creating relatively dense development – giving people access to stations and public transport interchanges, and on enabling people to get to schools, shops and other facilities without needing to drive. Figure 2.16 shows a typical compact-city-type development, achieving relatively high density near stations or other accessible locations.

Figure 2.16

A typical form of compact development, achieving relatively high density at accessible locations.

Resources should be used efficiently in the construction and operation of buildings and places. This should be considered in relation to orientation, drainage, energy, movement, waste, green space and current established standards. An energy strategy for an area or site should be based on an energy-hierarchy approach. This starts with reducing the demand for energy; goes on to supplying as much as possible of the energy requirement from on-site renewable or low-carbon sources; and finally specifies that as much as possible of the remaining demand comes from off-site low-carbon technologies, including decentralised and district sources.

Consider

- How the structure and form of a place make it efficient to use and maintain, for example by making it easy for children to walk to school.

- How well existing buildings or other elements are used, even if only for a short time.

- How the design of a place increases, or reduces, its need for energy through the creation of solar gain, overshadowing or cross-ventilation.

- How well water and waste are dealt with, for example allowing for community-based recycling and composting, and for excess surface water to be stored and used, where appropriate.

- How demand for energy can be minimised, and how energy can be created locally or with the fewest negative impacts on the environment.

Figure 2.17

Homes with very different appearances sitting side by side.

What the NPPF Says

‘Planning should … support the transition to a low carbon future in a changing climate … and encourage the use of renewable resources (for example by the development of renewable energy).’ (Paragraph 17)

‘Local planning authorities should not refuse planning permission for buildings or infrastructure which promote high levels of sustainability because of concerns about incompatibility with an existing townscape, if those concerns have been mitigated by good design.’ (Paragraph 65)

‘In determining planning applications, local planning authorities should expect new development to … take account of landform, layout, building orientation, massing and landscaping to minimise energy consumption.’ (Paragraph 96)

Appearance

The functional and aesthetic characteristics of a place are closely related to one another. Planners will be concerned with the visual appearance of places at a variety of scales. These will relate to the following:

- Townscapes

- Skylines

- Distant views

- Landmarks

- Local streetscape

- Relationships with neighbours

- Close-up views

- Proportions

- Building details

Many development proposals seek to create a familiar appearance intended to be popular, or to convey messages about the affluence, values and lifestyle of the owner through the architectural treatments used. Sometimes this is done by referencing older building styles. Where this is the case, great care is needed to ensure that well-proportioned and honest buildings and spaces are created, rather than a poor imitation of a particular style. Sometimes elements of a particular style or a supposed local vernacular (quoins, flintwork, columns, porches, carriage lamps and so on) are added without proper regard to whether the building’s proportions, storey heights and roof pitches also reflect the chosen style. This approach is rarely successful.

Figure 2.18

The identity of this place has been shaped by the buildings’ layouts, the planting, the materials, the uses and the passage of time.

Some developments are designed to look different from their neighbours, but to fit in with their context through their approach to bulk, height, position, rhythm and proportions. Figure 2.17 shows adjacent homes with a range of appearances. The overall height and position of the buildings are similar, but some are more visually successful than others. It is useful to consider how the materials, shape, roofscape and relationship of window to solid wall affect the appearance of each house. For example, the first two new homes (nearer the left of the picture) might seem more attractive than the third and fourth. They have more window space and less solid wall, pitched roofs, use wood and brick, and are set back as they rise, rather than overhanging, as the third new house does. All these characteristics could make them seem to fit in better. Or the third and fourth homes might be thought to be the most attractive, as they are balanced and uncluttered in design, with good proportions as individual entities. Planners need to consider why a particular approach to a development’s appearance has been taken, and how this fits with policies and priorities for the area. A design and access statement can help with this.

Consider

- How buildings and streets integrate with the area’s natural setting, and how they relate to the skyline and landmarks in the area.

- The appearance of the streetscape, and the role of plot dimensions, individual buildings, historic elements and building details.

- The expression and honesty of building designs, including how well appearance expresses function, and the visual clues to construction methods and materials used.

- The proportions of buildings and their elements, and how well these relate to the whole.

- How much thought has been given to the relations between one part of the development and another, between each part and the whole, between solid and void elements of the facade, and between the proposed development and its surroundings.

- The order expressed in designs, including the extent to which balance, repetition and symmetry contribute to a pleasing sense of order, where this is appropriate.

- The style or styles used, and whether this emulates a local vernacular, incorporating or interpreting the form and details of local traditional buildings.

- Whether the style used is done well, or if a few details have been mindlessly copied without capturing any of the essential identity of the original.

What the NPPF Says

‘Aim to ensure that developments … establish a strong sense of place, using streetscapes and buildings to create attractive and comfortable places to live, work and visit.’ (Paragraph 58)

‘Aim to ensure that developments … are visually attractive as a result of good architecture and appropriate landscaping.’ (Paragraph 58)

Identity

The interpretation of identity and its application to decisions is one of the biggest issues in planning. The objective of creating or maintaining a place’s distinct identity, often referred to as character, is the single most common feature of design policies in local authority development plans. A determination that development should ‘fit in’ to its local setting, respecting its valued identity, is one of the planning issues that most concerns the public and the councillors who represent them.

Often a planning policy on the issue of identity will say only that development should be ‘appropriate’ to its local context, without specifying what that might mean. However, planning should go beyond this, because understanding the identity and character of a place is essential in designing for that place or appraising a development proposal.

Identity is not something separate from a place’s other attributes and characteristics described in this chapter. It is a combination of all of them, as they have developed through the passage of time. Identity comprises the good and bad aspects, those that have existed for generations, the new parts, the empty spaces, the memories of those who have used the place, and the behaviours and feelings of those who inhabit it today. Planning – a political, process-driven system – has to deal with identity: considerations of historic context and design quality can help.

Chapter 12 discusses in more detail the role of historic conservation principles, policies and practices in design. Historic England (www.historicengland.org.uk) has published many guidance documents that set out how planning should consider and understand the evolution and significance of a place, a site or a historic asset and its setting, and how they contribute to creating a sense of place.

A number of approaches are available for identifying and interpreting the historic dimensions of present-day landscapes or townscapes:

Figure 2.19

The way a historic high street has grown and changed organically is part of its identity.

Figure 2.20

The identity of different areas within a town relate to layout, age, use and building form (each differently coloured area has its own identity).

- Historic identification is carried out to develop an understanding of how a place has evolved and how it is currently perceived.

- Historic landscape identification describes patterns and clusters of historic landscape identity types.

- Historic area assessments, based on wide-ranging research of documents and field surveys, provide an understanding of the historical development of an area such as a small town, suburb or village, or part of a larger settlement.

A place’s identity is made up of the current uses, how the place works, the patterns of movement, what the spaces are like and how they are enclosed, how adaptable and resilient the place is, how efficient it is in its use of resources, and what it looks like. Successful design depends on understanding how buildings, spaces and movement networks contribute to a place’s identity; how that identity has been shaped by the place’s ability to adapt in the past; and how aspects of its appearance have contributed to the place’s distinctiveness.

An understanding of these issues will be derived from local knowledge, and from local appraisals and assessments. It can be useful to understand how identity changes across a place, identifying different distinct areas, as shown in Figure 2.20. Such analysis can be used in setting requirements for, and assessing, development proposals. Appraisals will be part of the process of recognising what is there – not just the architecture and townscape, but every aspect of the place – and what is valued.

The existing identity of the place might not be positive. The site could be in featureless scrubland, industrial wasteland or a bleak landscape of big-box developments, or surrounded by houses that are generic in design. In such circumstances successful planning and design will depend on finding a few positive attributes the place does have, building on these and on thinking creatively to produce a new, positive identity.

Consider

- The things that constitute the special identity and distinctive nature of any place will not be the same for everyone.

- What evidence can be gathered to evaluate all the elements that contribute to identity before making planning decisions.

- That discussions over identity, or threats to what people hold dear, can be highly emotive.

- In some situations, discussions about identity are seen as a way to oppose a development, hoping to make the proposed scheme unviable or undeliverable.

What the NPPF Says

‘Local and neighbourhood plans should develop robust and comprehensive policies that set out the quality of development that will be expected for the area. Such policies should be based on stated objectives for the future of the area and an understanding and evaluation of its defining characteristics.’ Those policies should ‘respond to local character and history, and reflect the identity of local surroundings and materials, while not preventing or discouraging appropriate innovation.’ (Paragraph 58)

‘Planning policies and decisions should not attempt to impose architectural styles or particular tastes and they should not stifle innovation, originality or initiative through unsubstantiated requirements to conform to certain development forms or styles. It is, however, proper to seek to promote or reinforce local distinctiveness.’ (Paragraph 60)

The characteristics described in this chapter overlap, intermingle and support each other. They can also be thought about as separate planning issues or policy headings, and are indeed often used as such.