• Criminal law deals with those offenses against society. In most states, the Revised Code classifies and defines criminal offenses. Serious crimes such as murder, rape, arson, armed robbery, and aggravated murder are felonies. Misdemeanors include charges such as disorderly conduct and criminal damage to property. When these offenses are taken into court, the state takes the active role in pursuing the case as the plaintiff or offended party.

• Criminal law is the creation of legislation. Courts may decide that certain laws are vague or improper and therefore set them aside, but courts do not create laws.

• In most states, everyone is given the authority to arrest for a felony, whereas misdemeanor arrest authority is limited to law enforcement officers. Likewise, merchants and their employees have the authority to detain individuals in certain situations.

• Civil law has more to do with personal relationships and conflicts between individuals. Broken agreements, sales that leave a customer dissatisfied, accidental injuries, and divorce all fall under the category of civil law. In civil law cases, private citizens are the offended parties and the party found at fault is required to compensate the victim.

• The principal source of law in the United States is the English common law. This is law that was established over generations by common agreement among reasonable men as to what constituted acceptable and unacceptable conduct. In English common law, offenses such as treason, murder, battery, robbery, arson, larceny, burglary, kidnapping, and rape were all major crimes.

• When a case is heard before a judge, much of what will ultimately be the final decision is based on previous cases which have been decided. Precedence is that which has occurred before and has some impact on the case currently being decided. These previous decisions and precedence form case law.

• The U.S. Congress and state legislatures have the power to enact laws that define additional crimes. The authority to define additional crimes comes from the U.S. Constitution and state constitutions. In most states, the state legislature enacts laws which may ultimately be contested in court.

• The U.S. Constitution sets forth basic rights of all individuals. In doing so, it places limitations on the conduct of the government and its agents.

• Tort law is the primary source for the authority of security personnel. It allows a person ho has been injured or damaged by another to sue that person for the injury or damage inflicted. Tort law differs from criminal law in that it involves private parties seeking relief for loss and not punishment of the offender.

• If a person is arrested, they must be taken before the nearest judge or magistrate without unnecessary delay. The court may proceed with the trial in the case of a misdemeanor charge unless the accused demands a jury trial or requests a continuance.

• If a charge is a felony, the judge or magistrate conducts a preliminary hearing, which is an informal process designed to determine if reasonable grounds exist for believing the accused committed the offense. If such grounds do not appear, the charges against the accused will be dismissed.

• A grand jury is required in many states to consider the evidence in any felony case. Grand juries usually consist of 23 citizens, of whom 16 constitute a quorum, which are enough to hear the evidence. Grand jurors hear only the prosecutor’s case. The accused is not permitted to offer evidence to refute the prosecution. Misdemeanor cases are not handled by grand jury action but by information filed by the prosecuting attorney usually upon receipt of a sworn complaint of the victim or witness who is knowledgeable about the incident.

• The Sixth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution states that a person accused of a crime shall have the right to a speedy and public trial by an impartial jury of the state and district where the allege offense occurred. Most state constitutions determine what is considered a speedy trial.

• In most states, for felony cases, 12 jurors must unanimously agree on a decision. If the jury is unable to arrive at a verdict and the judge believes that additional deliberations will not change the deadlock, a mistrial will be declared as a result of the hung jury. The prosecution must then decide whether it wants to prosecute the case again. In misdemeanor cases, four of six jurors must agree on a verdict.

• If the jury decides the defendant is not guilty, he or she will be immediately freed and the matter is dismissed. If the defendant is found guilty, an appeal is usually made. Depending upon the circumstances, a defendant may be released on bail pending appeal.

• If the jury finds the defendant guilty, they will often be asked to determine the penalty for the crime (fine, imprisonment or both) if the defendant is on trial for murder or rape.

• If the accused is convicted in trial court, he or she may appeal the case to a higher level. During the appeal process, no new evidence is presented. There is no jury to determine guilt. The court examines the written record of the trial and considers whether the trial was properly conducted, whether matters prejudicial to the rights of the accused occurred, and whether the evidence presented to the jury was legally obtained and properly presented to the jury.

• If the original verdict is affirmed, then the original conviction remains intact. If the verdict is reversed, the defendant is freed pending whether a new trial is ordered. During some appeals, the reviewing court will issue an order to retry the case. This is often the case when evidence presented in the original trial has been ruled admissible.

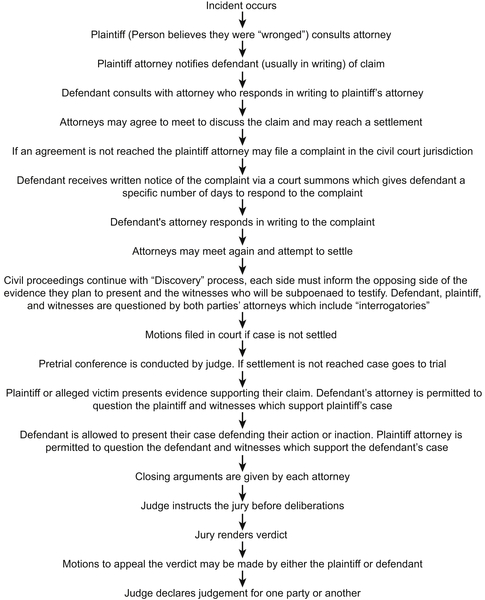

• In civil court, the person seeking compensation for either damages, lost revenue, break of a contract, etc., is the plaintiff, whereas the person who is alleged to have committed the wrong against the plaintiff is the defendant.

• In recent years, as more and more cases are filed in civil court, arbitration has become more popular. Arbitration bypasses a true civil court case and allows the two disputing parties to have their case settled by an objective, independent arbitrator (usually an attorney). By agreeing to this type of court procedure, the parties can normally obtain a decision in a fraction of the time it requires for a case to be tried in civil court.

• Most states regulate civil law for actions between persons, corporations, local governments, etc. Civil law developed over the years to resolve conflicts among people that may not necessarily involve criminal behavior or action. In civil law proceedings, one party (an individual or group of individuals) brings action or sues another party for a variety of reasons including: breach of contract, vicarious liability, negligence, false arrest or imprisonment, malicious prosecution, assault, battery, trespass, emotional distress, defamation, invasion of privacy, excessive use of force, etc.

• Many of the reasons cited above which involve civil law are also considered to be a tort. Tort is a breach of duty—a failure to act on the party of one party to another. In civil law proceedings when one party sues another, the plaintiff (person who initiated the legal action) will normally seek money from the defendant (person who is being sued).

• Torts differ from crimes in that for a crime to have occurred, intent must be proven.

• Civil cases or lawsuits are decided by a judge or jury after attorneys for both sides have presented their cases. In civil lawsuits, the plaintiff needs only to prove their claim as measure by a preponderance of the evidence. Preponderance of the evidence means that at least 50.1% of the evidence presented in the case supports one person’s claim more than the other.

• A claim of vicarious liability is often made in civil lawsuits involving security personnel in order to hold the employer of the security officer completely or partially responsible. Vicarious liability holds an employer responsible for the actions of the employee or security officer.

• Negligence is defined as causing injury to a person or damage to property through a person’s actions or by failing to act with regard to the safety and rights of others.

• False imprisonment is defined as the unlawful confinement, restriction, and detention of another. False arrest is the unlawful arrest of another. Charges of false arrest and false imprisonment are often made together because they may have resulted out of the same.

• Assault and battery are actually different offenses but they often are associated because an assault often occurs just before the battery. Excessive force is the ultimate result when an actual assault and battery claim is proven as a result of the actions of a security officer.

• Battery occurs when an unauthorized touching or contact occurs. It is not necessary to prove that any real harm resulted but only that the contract was not authorized. Assault requires that a least some threatening gesture occurred. In addition, the victim must have thought the gesture would result in harm.

• Excessive force is a claim that is often the result of a charge of assault and battery having been made against a security officer. Security officers are permitted to use force in carrying out their duties to protect themselves, others, and property.

• The law permits a security officer to use reasonable force to defend himself.

• Defamation is a tort which takes two forms, libel and slander. Libel is defamation in a written form, whereas slander is defamation in an oral or verbal form. Defamation is defined as injuring the reputation of another by publicly uttering untrue statements.

• Truth is always a defense against a claim of defamation.

• Security officers must always remember that most of their actions pertaining to dealing with others will always be reviewed and reexamined if a question occurs to the conduct of the security officer. Security officers should realize that their actions are observed much like watching a fish in a fishbowl. The actions or behavior of security officers that are considered unreasonable will undoubtedly develop into an unpleasant and possibly costly ordeal for the officers. However, security officers who maintain their composure at all times and rely upon the skills developed in this training manual will usually not be subjected to civil lawsuit alleging a tort.

• In most states, private citizens and security officers are not liable for civil damages when they administer emergency care or treat a person at the scene of an emergency.

• Financial compensation is usually awarded to the plaintiff when they have successfully shown that the actions of a security officer were not warranted and resulted in some type of injury.

• Compensatory damages compensate the injured party for an injury sustained and nothing more; these damages simply make good or replace the loss caused by the wrong or the injury.

• Punitive damages may be awarded where the actions of the defendant (security officer) have been judged to have been intentional and deliberate. These damages are given to the plaintiff over and above the financial compensation received for compensatory damages and are awarded to punish the plaintiff.

• Intentional torts allow for both compensatory and punitive damages to be awarded. Unintentional torts allow for only compensatory damage awards.