Job:02-30034 Title:RP-Fashion Design Ref and Spec Book

#175 Dtp:225 Page:153

Book

e:152

146-161_30034.indd 153 2/27/13 3:01 PM

Rendering 15 3

(Text)

14

e

-

r

t

Many are of the opinion that designers should take anatomy classes to help improve their

sketching. When it comes to the art of fashion, these classes better serve the fashion illus-

trator. On the other hand, anatomical study will have an impact on designers’ patternmaking

skills. Anatomy provides them with an understanding of the structure and mechanics of the

body, from which they can gain a greater appreciation for how clothing will fit and flow around

the human form.

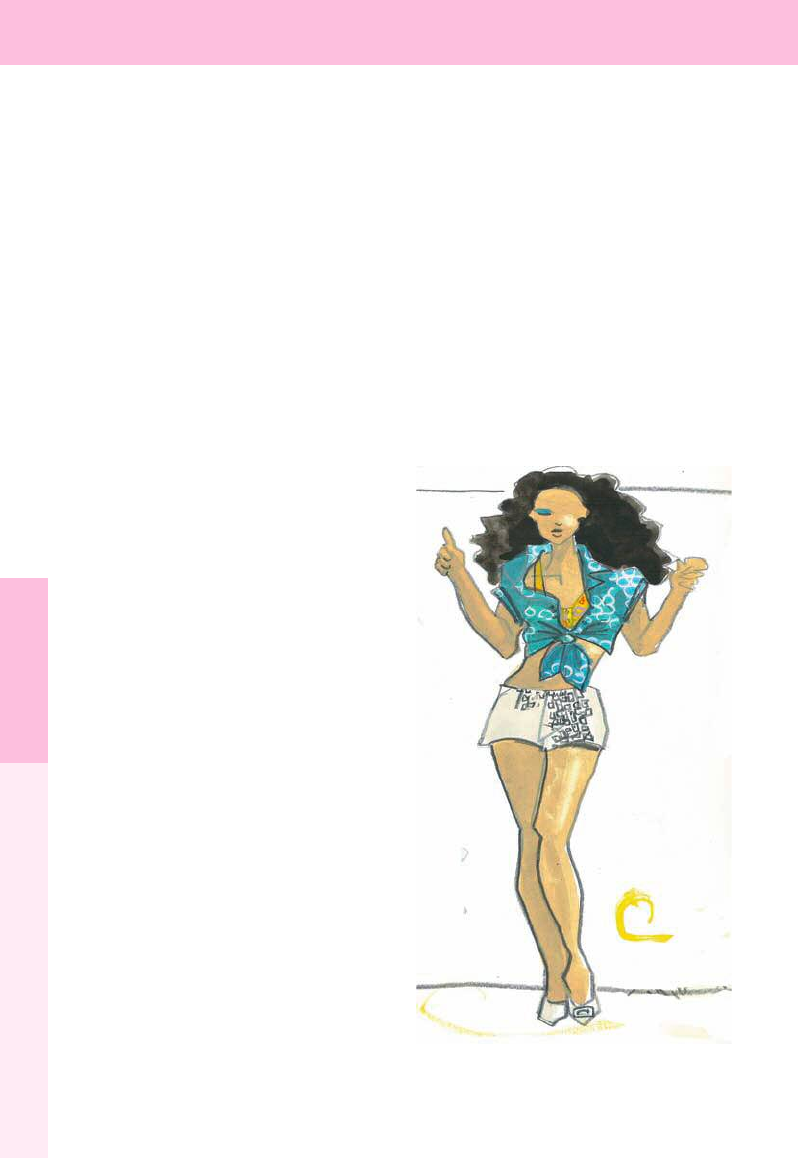

Designers should remember to draw only what they would see from a particular vantage point.

For instance, on a front view drawing of a garment the side seams would not be visible. If

there is a reason to show the side seams, the figure should be rotated—front, side, three-

quarter, and back views—to display the feature in those areas. When a designer chooses to

place two or more figures on a page, the poses should reflect the desired dynamic between

them. These poses should also create good negative space around and between the figures.

A designer wants the viewer’s eye to focus on the clothing, first and foremost. A natural border

of space is recommended when determining where to place the figure on the page. To best

serve the clothing in a sketch, poses should not distort the garments, but rather, allow for a

clear interpretation of how they are made and how they hang on the body. Keeping arms below

the shoulder line, bent knees to a minimum, and arms or long hair from obscuring the design

are few general guidelines that will help the croquis retain its value as a communication tool.

Fashion gure in 9-head

proportion—shadow-mapped

fashion sketch

RENDERING THE HEAD

Face

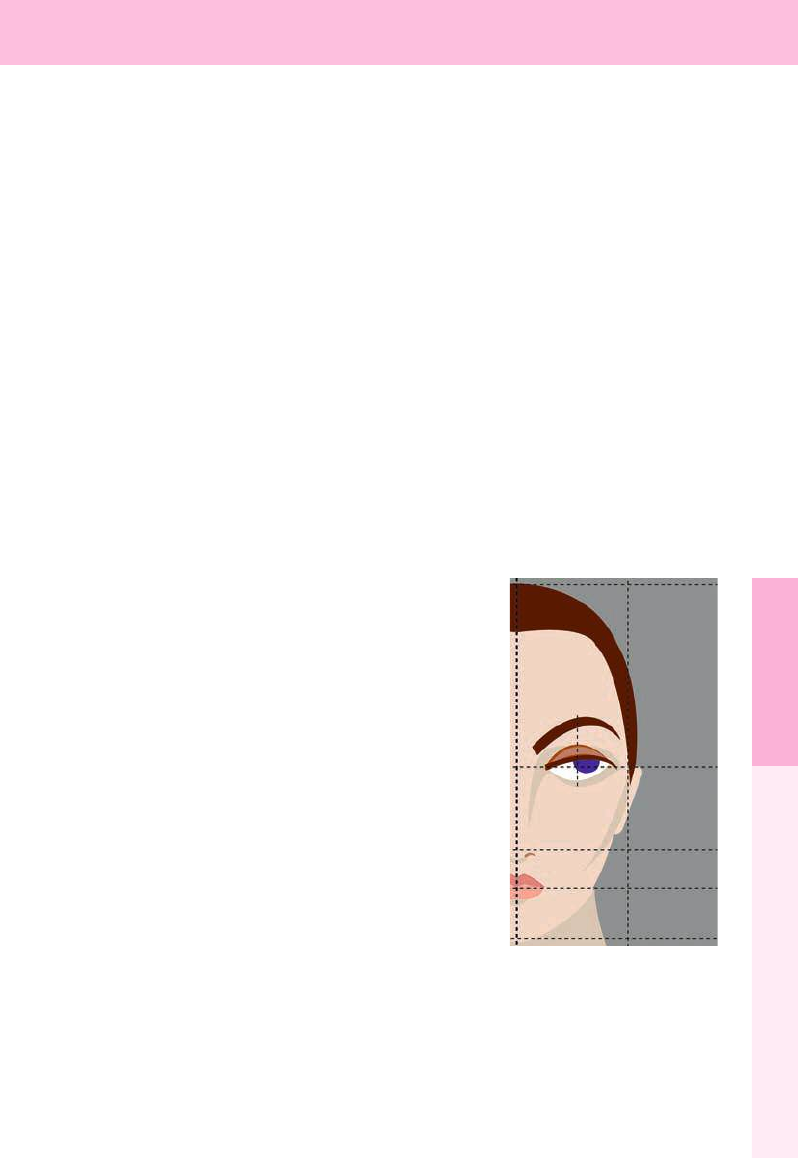

Facial structure, like that of the body, is varied. Moreover,

different cultures have their own standards of beauty. The

“rules” that provide a baseline for the basic proportions of

the face, therefore, rely heavily on balance. Designers have

the discretion to adjust measurements to capture the es-

sence of their ideal or the customer for whom they are creat-

ing a sketch. The face begins with an inverted egg shape,

bisected by a centerline, with a corresponding perpendicular

line to mark the chin and top of the head. Half way from the

top of the head to the chin would indicate where the eyes

are to be positioned. The area below the eyes is then halved

to find the position for the nose. The mouth can be placed in

the middle of the area between the nose and the chin. The

nose and the mouth are centered, while the eyes are dis-

tributed in the space of four eyes. Working from the center

outward, one eye will represent the space between the eyes.

The two actual eyes will be placed on either side, which

should allow for the space of half an eye between the eye

and the side of the face. The oval can be sculpted on either

Job:02-30034 Title:RP-Fashion Design Ref and Spec Book

#175 Dtp:225 Page:153

Book

e:152

146-161_30034.indd 153 2/27/13 3:01 PM

Job:02-30034 Title:RP-Fashion Design Ref and Spec Book

#175 Dtp:225 Page:154

146-161_30034.indd 154 2/27/13 3:01 PM

15 4 THE FASHION DESIGN REFERENCE + SPECIFICATION BOOK

(Text)

14

side by two parallel lines to the face. At the level of the mouth, these lines can bend inward

to meet the chin line, defining the jawline. Depending on scale, the ears usually line up on top

with the eye and end somewhere between the nose and the mouth. The same proportions are

valid for profiles with the exception of the volume of the nose, lips, and chin protruding off the

egg at the precise locations.

Eye

The eyes start with an almond shape. The centerline between both tips establishes the tilt of

the eye. A third line with less of an arc is drawn from one tip to the other to create the lid. How

low the lid is drawn will determine how open the eye seems to be. A circle representing the iris

is placed within the original almond shape. The lid line should cut off the top of the circle de-

picting the iris, which should appear to be perfectly round, although obscured by the eyelid. If

the iris is rendered as a complete circle the result will be a wide-eyed, shocked, or frightened

expression. When rendering the iris in color, omitting color or adding a white accent in the

shape of a small crescent creates the illusion of glistening light.

Lashes can be drawn from the center of each lid outward, with an emphasis on quality of line,

so that the drawing tool lifts off the page at the end of each lash. Three to five top lashes are

plenty considering the size of the average croquis (obviously, the larger the rendering the more

details it can handle). A point above of the eye closest to the center of the face is the starting

point for the eyebrow. The arch can follow the angle of the top of the almond and extend as far

as three-quarters of the eye before it breaks to level off.

Nose

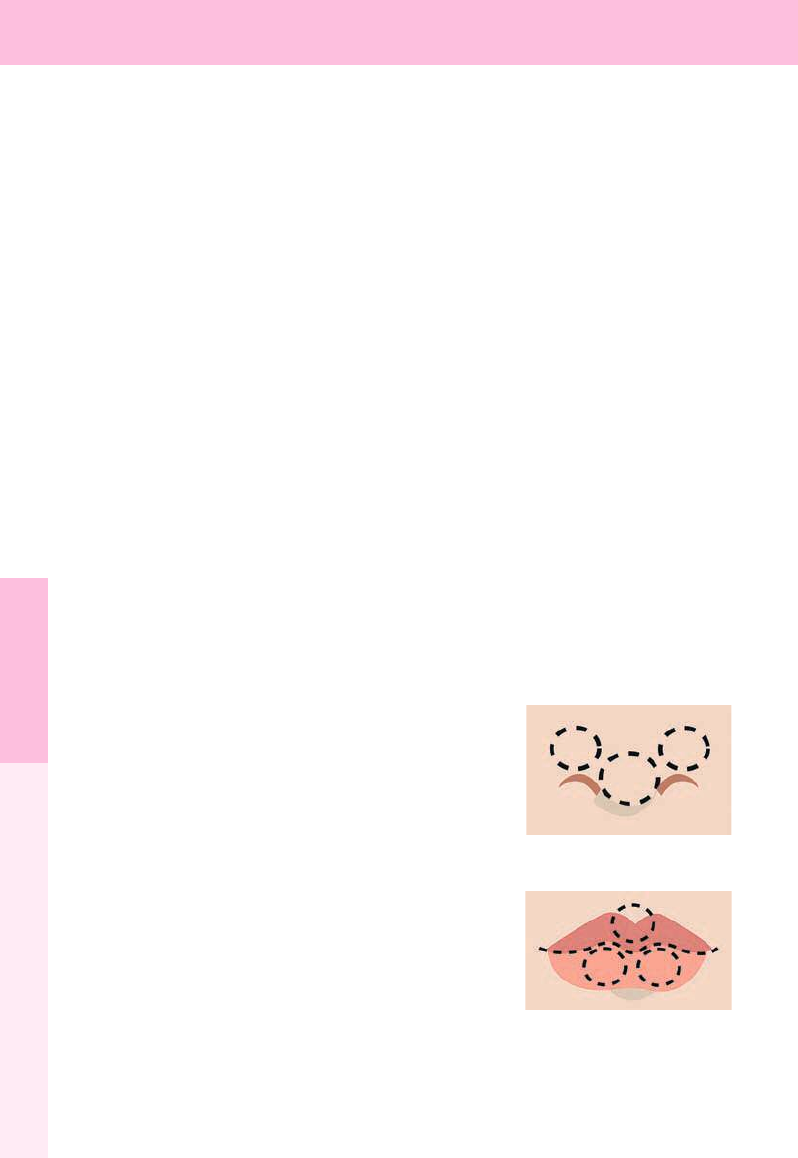

Nose

Mouth

H

Rendering the nose is more about shadows than lines. Three

circles will define the scale of the tip of the nose and the

area over the nostrils. Under the spots where these circle

touch are spaces where arcs can be drawn to show the nos-

trils. In most fashion sketches, these markings alone can be

enough to create an impression of the nose.

Mouth

Building the shape of the mouth can be done using three

circles stacked into a pyramid. The hill-like space between

the circles will determine the opening of the mouth. Cutting

a V or U shape out of the top circle establishes the center of

the top lip, and drawing sloping lines to connect it with the

sides of the mouth will complete the archer’s bow silhouette.

A straight (or slightly indented) line between the bottom two

circles creates an area for shadow under the bottom lip. This

Job:02-30034 Title:RP-Fashion Design Ref and Spec Book

#175 Dtp:225 Page:154

146-161_30034.indd 154 2/27/13 3:01 PM

Job:02-30034 Title:RP-Fashion Design Ref and Spec Book

#175 Dtp:225 Page:155

Book

e:154

146-161_30034.indd 155 2/27/13 3:01 PM

Rendering 15 5

(Text)

14

p

e

e

w

s

,

e

g

ar

can also be connected with the sides of the mouth. When

rendering the lip in color, making the upper lip a shade darker

will create a more three-dimensional look.

Complexion

The complexion of the figure may or may not be a direct re-

flection of the ethnicity designers are going for. How they com-

bine color with modified features will allow them to develop

an international rainbow of models. The place to start is the

level of light or dark (very fair, fair, midtone, tanned, dark, very

dark) that the designer wants to establish. Once the range is

selected, it is a matter of mixing color in the equivalent level

of white, cream, tan, or brown with colors that will tint them in

the direction the designer desires. For Caucasian skin, pure

white will create the appearance of alabaster, but adding red

to it can result in a ruddy complexion. Tinting tan with olive

can give the impression of swarthy Mediterranean skin, while

adding a little black to a darker brown can create a rich Afri-

can skin tone. Adding the tone-on-tone of freckles to any color

makes for a completely new look. As in all things, the choices

and customizations designers make will reflect their aesthet-

ics and how their customers see themselves. Keep the visual

focus of the presentation on the garments and use skin tones

to enhance your presentation and color story.

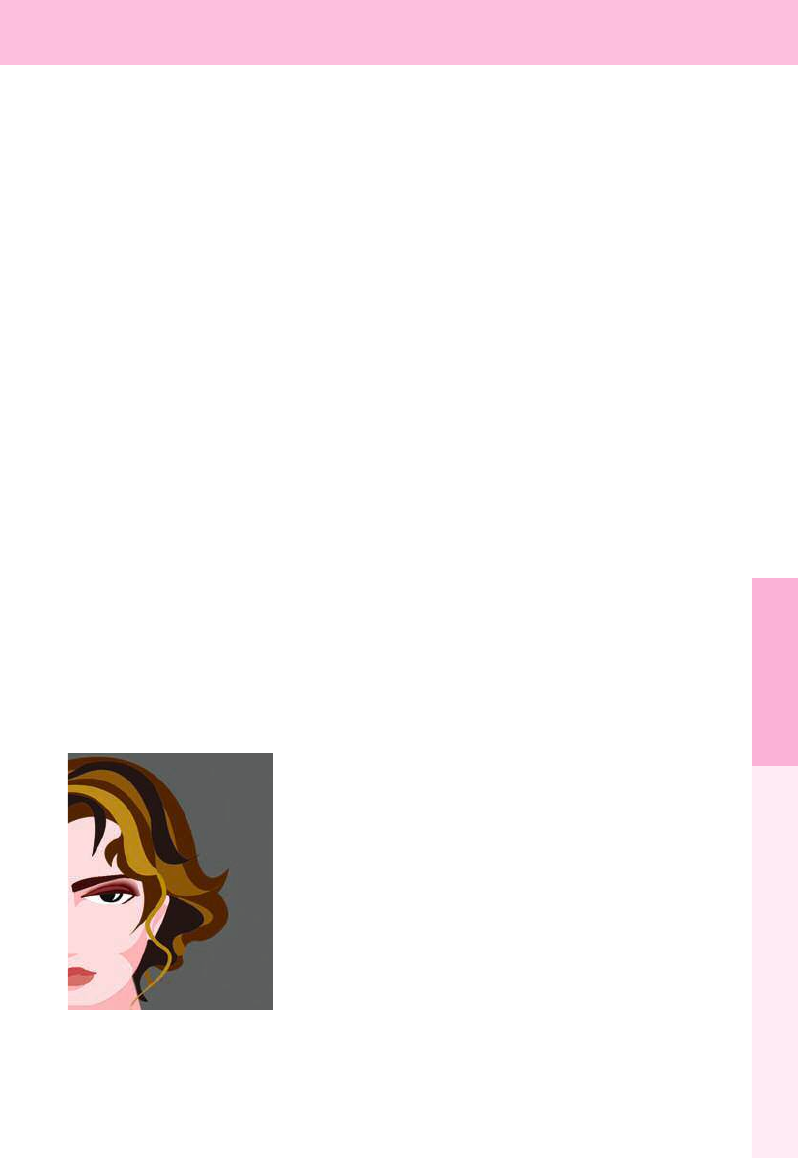

Hair

When rendering hair, it should be broken down into sections

and locks. Hair stylists use a standard technique for section-

ing hair for a haircut, called seven-section parting, which

designers can borrow for creating a hairstyle on their croquis.

These sections are top, temple/right side, temple/left side,

right crown, left crown, right nape, and left nape. Dividing the

hairstyle among them helps to plot out what it will do at each

point (stand up, curl, lie flat, etc.) as well as how long and at

what angle it will be cut. Although a sketch might represent

a frontal view, designers should clearly understand what is

happening in the back of the head and what part of it will be

seen from the front. Once a hairstyle is mapped out, the base

shapes can be rendered in a medium tone of the desired

color. Highlights and lowlights (or shadows) are added as ac-

cents for each section. Fine details can be introduced in the

form of tufts, wisps, or strands of hair to finish off each sec-

Hair

Job:02-30034 Title:RP-Fashion Design Ref and Spec Book

#175 Dtp:225 Page:155

Book

e:154

146-161_30034.indd 155 2/27/13 3:01 PM

Job:02-30034 Title:RP-Fashion Design Ref and Spec Book

#175 Dtp:225 Page:156

146-161_30034.indd 156 2/27/13 3:01 PM

15 6 THE FASHION DESIGN REFERENCE + SPECIFICATION BOOK

(Text)

14

tion. The texture of hair must also be designed. Will straight hair be blunt, curl under, or flip

out? Will curls be large and loose waves or small and tight ringlets? How will sections of hair

be swept up to create an updo? How will the scalp be sectioned for braids or dreadlocks? The

thickness and length must be determined as well.

Makeup

The application of cosmetics on the croquis should be undertaken with the same kind of plan-

ning and artistry with which real makeup is applied. After laying down a base color for the skin,

a second layer of the same color can be used to create shadows. Once these shadows have

established the contours of bone structure, designers can add eye shadow, rouge, and lip

color. A thin wash of color over the skin tone will create a natural look, while a heavier treat-

ment will result in something more theatrical. A light touch is required for eyeliner, lashes, and

brows. These details help to define the eye, and it is easier to add than remove.

ca

tu

b

P

T

o

ca

a

A

ch

th

b

a

sw

to

To

b

s

to

q

A

u

th

C

ty

of

co

sa

A

fr

q

st

b

RENDERING FABRIC

Besides having a grasp on the structure

of the body and facial details, the de-

signer must, of course, be able to capture

textiles, construction, and ornamentation

as they relate to the garments they are

depicting. Fabric that is manipulated in

three dimensions must be translated into

two. Flares, for instance, might be trum-

petlike when the garment is made out of a

crisp, stiff fabric such as taffeta or more

flutelike were the same style of garment

to be made of chiffon.

The roundness of gathered fabric is sub-

ject to the same idea when it comes to

ruffles, shirring, smocking, quilting, and

puffs. When rendering each pucker and

release of a gathered fabric, the designer

should remember that each little divot is

in fact a shadow and not a line.

Pleats, on the other hand, have a crisp

crease in the folds of tuck, box, accor-

dion, and fan pleating. Irregular pleating

Job:02-30034 Title:RP-Fashion Design Ref and Spec Book

#175 Dtp:225 Page:156

146-161_30034.indd 156 2/27/13 3:01 PM

Job:02-30034 Title:RP-Fashion Design Ref and Spec Book

#175 Dtp:225 Page:157

Book

e:156

146-161_30034.indd 157 2/27/13 3:01 PM

Rendering 15 7

(Text)

14

e

-

n,

d

can take many forms and therefore variations should be studied closely before trying to cap-

ture them on the page. This style of pleating, called primitive, mushroom, or broomstick, has

been explored by designers from Mariano Fortuny to Mary McFadden to Issey Miyake in his

Pleats Please line.

To draw fabric that is draped by folding or tying as well as fabric that falls into cowls or cas-

cades, a designer must be familiar with the nature of the fabric and how it will respond to

any of these manipulations.

Another textile issue the designer faces with the creation of a sketch is pattern. Stripes,

checks, plaids, and overall patterns each present their own challenges. As in textile design,

the fashion designer creates a motif, then decides on its scale and repeats in relation to the

body. Grids that represent the direction of grainlines help to plan out how a pattern will wrap

around the form. The size of each repeat determines the size of the grid. Holding a fabric

swatch up to the body can help a design illustrator visualize how a motif will fit from shoulder

to hip and use the scale to fit the body they have drawn.

To show textiles as texture, the designer’s focus is on rendering with color. A sheer fabric

becomes a filmy wash of color layered over skin tone and any other fabrics it rests on in the

sketch. Lace work is also layered over other colors, but demands strong bias cross-hatching

to create the illusion of netting on which the pattern of the lace is built. Feathers and fur re-

quire layers of color to create depth at the center and a wispy lightness along the perimeter.

Any surface texture will affect the line quality at the edges of the silhouette, be it smooth or

uneven. Knits are depicted by building up ribs, cables, or twists and stitch details to create

the appropriate surface texture for the bulk of the fabric.

Color-on-color surfacing—usually pencil over watercolor—can be used to create different

types of weaves—linen, raw silk, denim or twill, and corduroy, for example. The desired level

of roughness is influenced by the density of threads, nubs, and slubs in the weave. The vis-

cosity of paint can be applied thickly for velvet, leather, and suede or in thinner wet washes for

satin, ombre stripes, dip-dye, or tie-dye.

Adding any type of embellishment or decorative detail (embroidery, sequins, beads, fringe,

frogs, bows, piping, decorative stitching, appliqué, passementerie) is the final stage and re-

quires delicate pencil, marker, or even watercolor work. Each type of detail requires individual

study, be it the direction of threads, the overlap pattern of sequins, the shape of stitches or

beads, or the twist and gauge of cording.

Job:02-30034 Title:RP-Fashion Design Ref and Spec Book

#175 Dtp:225 Page:157

Book

e:156

146-161_30034.indd 157 2/27/13 3:01 PM

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.