Job:02-30034 Title:RP-Fashion Design Ref and Spec Book

#175 Dtp:225 Page:248

248-255_30034.indd 248 2/27/13 6:38 PM

24 8 THE FASHION DESIGN REFERENCE + SPECIFICATION BOOK

(Text)

Chapter 25: Awareness

The world of fashion has begun to recognize many concerns that go beyond

perfecting the silhouette of a dress, giving rise to a new generation of con-

scious designers. Content as well as intent play into the designer’s creative

process and business strategy. Designers are asked to consider how their daily

operations and the imagery they produce affects the environment, fair trade

practices, self-esteem, cultural identity, intellectual property, and indeed, the

future well-being of their industry.

CONSCIOUS PRODUCTION

Green Design

Green fashion has come to mean something beyond clothing that is more statement than

style. Green thinking has become a natural extension of the design process. Leading design-

ers in the market are always ready to shift gears, to map out a place for themselves on the

new frontiers of fashion. They see the environmental concerns that have changed the way

fashion is approached as opportunities rather than difficulties, for they open up new markets

for designers and new kinds of products for the consumer.

The emphasis on organic pesticide-free fibers and production and delivery methods that

reduce environmental impact have created new specializations. For example, Massachusetts-

based Darn It! Inc. found their niche by helping to maintain the quality of products made over-

seas by correcting problems and finding solutions to warehousing and distributing goods.

Designers face environmental issues when debating the merits of local or overseas produc-

tion. Do they go overseas (for large-scale production and speed) or stay local (smaller produc-

tion runs with reduced environmental impact)? Re-examining the development of a product to

identify where processes can be modified to serve a greener standard will vary greatly based

on whether their work is exported or kept regional.

Fashion is based on conspicuous consumption and constant change. The designer of the

future will embrace alternative practices that still feed the hunger for what is current and excit-

ing. Fashion schools have begun to develop programming that addresses sustainability, gen-

erating a new kind of designer who repurposes garments, deconstructing and reassembling

them in creative ways to produce entirely new garments. These eco-friendly designers use old

clothing, remainders, closeouts, and overstocks—all goods that might otherwise end up in

a landfill.

Photograph by Luis Robayo/AFP/Getty Images.

25

Job:02-30034 Title:RP-Fashion Design Ref and Spec Book

#175 Dtp:225 Page:248

248-255_30034.indd 248 2/27/13 6:38 PM

Job:02-30034 Title:RP-Fashion Design Ref and Spec Book

#175 Dtp:225 Page:249

Book

e:248

248-255_30034.indd 249 2/27/13 6:38 PM

24 9

(Text)

-

-

t-

d

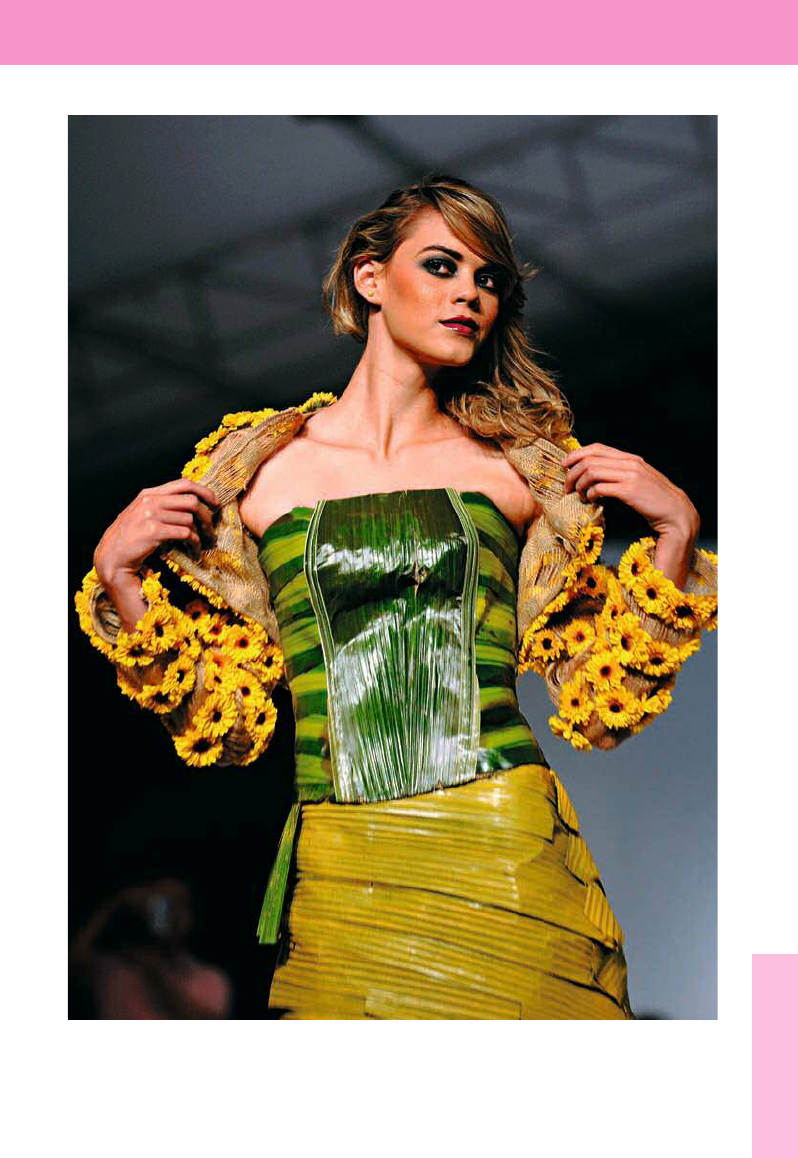

Pablo Cesar Dorado, Eco-friendly Design, Bio-Fashion Show, Cali, Colombia, 2008

Photograph by Luis Robayo/AFP/Getty Images.

25

Job:02-30034 Title:RP-Fashion Design Ref and Spec Book

#175 Dtp:225 Page:249

Book

e:248

248-255_30034.indd 249 2/27/13 6:38 PM

Job:02-30034 Title:RP-Fashion Design Ref and Spec Book

#175 Dtp:225 Page:250

248-255_30034.indd 250 2/27/13 6:38 PM

2 5 0 THE FASHION DESIGN REFERENCE + SPECIFICATION BOOK

(Text)

Fair Trade

Ethical fashion is produced under decent conditions for fair wages. Disadvantaged communi-

ties run the risk of being exploited, making third-party certifiers, for example, the Fair Trade

Federation and Transfair USA, necessary. A transparent supply chain will help to avoid sweat-

shop situations, with every step along the production path documented and information easily

accessed by everyone from the designer to the consumer.

Fair-trade safeguards also help to create sustainable economies for otherwise disenfran-

chised regions. They are a way for designers to connect with local artisans who would normally

not have a presence in the marketplace. Designers can also be instrumental in popularizing a

local product or service by adopting, protecting, and marketing it.

Those who labor to produce a designer’s product constitute the front line of fashion. Equitable

compensation is one more way a designer can do the right thing. In addition to earnings and

hours, many fair trade agreements ensure long-term commitments as well as investments in

the community, such as education and health initiatives.

Caring and Charity

“Animals are not ours to eat, wear, experiment on, or use for entertainment” is the slogan of

PETA, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. As it relates to fashion, animal-rights activ-

ism is concerned with the farming of animals for fur, the use of animals in entertainment, and

animal testing. Designers will need to decide to what degree they will embrace or reject the

implications of cruelty to animals for the sake of fashion.

The glamour and excitement of fashion has consistently drawn charities to designers as a way

to build awareness of and raise money for their cause. The Council of Fashion Designers of

America/CFDA Foundation has spearheaded campaigns and events such as Fashion Targets

Breast Cancer and Seventh on Sale (to benefit HIV/AIDS research). These are among the

most visible charities in the fashion industry, but education, poverty, hunger, and many other

causes are worthy beneficiaries. Giving back and showing that fashion cares is an important

part of designers’ relationship with the communities they serve. Designers might donate gar-

ments for auctions or put on lavish high-ticket fashion shows to benefit their charity of choice.

PROJECTED IMAGES

Sense of Self

Faces with character and bodies with curves need not fall under the category of fashion flaws.

How far has fashion gone when perpetual dieting and plastic surgery remain the only ways to

achieve the latest ideal of beauty? Nor should age be relegated to a second tier in the fashion

hierarchy. The boomer generation represents a gray glamour all its own. Living longer today

also means living better, resulting in vibrant and vital lifestyles—something that designers are

in an ideal position to amplify.

It

c

o

o

e

p

m

ti

T

ch

at

s

a

h

T

th

w

sa

b

25

Job:02-30034 Title:RP-Fashion Design Ref and Spec Book

#175 Dtp:225 Page:250

248-255_30034.indd 250 2/27/13 6:38 PM

Job:02-30034 Title:RP-Fashion Design Ref and Spec Book

#175 Dtp:225 Page:251

Book

e:250

248-255_30034.indd 251 2/27/13 6:38 PM

Awareness 2 51

(Text)

y

ly

a

e

-

d

y

.

.

n

e

It can be argued that adhering to established standards of beauty (however arbitrary) can

contribute to personal and professional success. But when these standards are distorted or

out of step with the society that is embracing them, its members are susceptible to poor self-

esteem, depression, body dysmorphic disorder, anorexia/bulimia nervosa, or any number of

physical and psychological complications that relate to a false self-image. Fashion designers

must realize that, one way or another, they are helping to perpetuate or prevent these destruc-

tive patterns.

The French fashion industry, supported by the French Minister of Health, has introduced a

charter of good conduct that encourages the use of models with diverse body types, in an

attempt to avoid potentially dangerous influences on young women. Promoting healthy body

sizes instead of idealizing unhealthy ones builds healthier body images. Spain and Italy have

also taken steps to ban from fashion shows models whose Body Mass Index falls below the

healthy range (18.5–24.9, as classified by the World Health Organization).

The Dove Campaign for Real Beauty is based on awareness and action. Leading by example,

the company has produced advertising and programming designed to educate and empower

women of all ages, body types, and ethnicities. Integrating all types of beauty sends a mes-

sage of acceptance to the consumer as well as a challenge to the rest of the fashion and

beauty industry.

Ad from Dove Campaign for Real Beauty

Photograph courtesy of DOVE)/Unilever.

25

Job:02-30034 Title:RP-Fashion Design Ref and Spec Book

#175 Dtp:225 Page:251

Book

e:250

248-255_30034.indd 251 2/27/13 6:38 PM

Job:02-30034 Title:RP-Fashion Design Ref and Spec Book

#175 Dtp:225 Page:252

248-255_30034.indd 252 2/27/13 6:38 PM

2 5 2 THE FASHION DESIGN REFERENCE + SPECIFICATION BOOK

(Text)

Cultural Identity

People from every corner of the globe buy into fashion, and yet there is a disproportionate

representation of different ethnicities and body types in the design field as well as among

the models on the runways and in the pages of fashion magazines. The perpetuation of a nar-

row definition of beauty contributes to racial bias. Moreover, the bottom line has advertisers

crafting very culture-specific images designed to harness a particular purchasing power. But

how can the fashion industry in the twenty-first century justify this imbalance? As the public

becomes more aware of the issue, they realize that if they are being asked to invest in the

products, they are entitled to see themselves represented in the fashion ads, in the editorials,

and on the catwalks.

Whatever their background, designers can address the fact that the exclusion of models of

color limits the potential of fashion. A precedent was set in 2008 when CFDA president Diane

von Furstenberg reached out to designers in an effort to encourage them to be diverse in their

runway presentations, although many of the shows remained whitewashed. This is not an

argument for enforcing multicultural quotas. What is important is that designers expose them-

selves to many different cultures and recognize that their business is supported by a range of

racial backgrounds.

Former model and agency owner Bethann Hardison has initiated a public discussion about the

relationship between black models and the fashion industry. History shows that black models

have made names for themselves. Dorothea Towles launched her modeling career in the early

1950s working for Christian Dior, Elsa Schiaparelli, and Pierre Balmain. Helen Williams was

the first prominent black model in the United States in the 1960s. Mounia was the first black

model on the Yves Saint Laurent runway. Naomi Sims appeared on the cover of Life magazine

in 1969, accompanying an article about new black models. Beverly Johnson was the first black

model to appear of the cover of Vogue, in August 1974. Pat Cleveland became a 1970s super-

model and muse to designer Stephen Burrows. Iman appeared in Vogue in 1976, her first job.

More recently, Veronica Webb, Naomi Campbell, Tyra Banks, Alek Wek, and Jourdan Dunn have

all had a strong presence. Observing the dates associated with each model, though, the ques-

tion becomes, Does the industry believe there is only room for one model of color at a time?

The current wave of Brazilian models, which include Gisele Bündchen, Adriana Lima, and

Alessandra Ambrosio, has taken fashion by storm. Yet they represent only a small fraction of

Hispanic beauty when one considers how diverse those origins are: European (Spain), Central

American (Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama), South

America (Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, Ven-

ezuela), Caribbean (Cuba, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico), North America (Mexico, United

States), Africa (Equatorial Guinea), and Oceania (Easter Island). Asian models have a very low

profile in fashion, but the number of new faces is growing: Devon Aoki (Japanese-American),

Han Jin (Korean), Yoon Sun Kim (Korea), Lakshmi Menon (Indian), Hye Rim Park (Korean-

American), Ling Tan (Malaysian), and Ai Tominaga (Japanese). The launch of Vogue China has

contributed to the growing awareness of Chinese models, including Xiaoyi Dai, Du Juan, Emma

Pei, Audrey Quock, Mo Wandan, Liu Wen, and Sonny Zhou.

D

Photograph by Andrew H. Walker/Getty Images for IMG.

A

D

H

C

M

C

P

O

N

A

I

L

25

Job:02-30034 Title:RP-Fashion Design Ref and Spec Book

#175 Dtp:225 Page:252

248-255_30034.indd 252 2/27/13 6:38 PM

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.