VOICEOVER

In This Chapter

• Planning for Voiceover

• Choosing a Sound Studio

• Casting Actors

• Recording Voiceover

• Voiceover Checklist

10.1 I

NTRODUCTION

Q

uality voiceover in a game is becoming an expectation of players. Players

want to be immersed in a game world, and that means the charac-

ters must be believable and speak in a way that fits the game world.

Great voiceover work adds to a game’s appeal and makes a good game better.

Conversely, poor voiceover work detracts from the game experience and makes

a good game seem below average.

Because of this desire to fully immerse the player in the game world,

voiceover work is also becoming more complex and, thus, more challenging to

manage. There are more characters, more lines of dialogue, and more diverse

uses of dialogue within the game. For example, Tom Clancy’s Ghost Recon had

about 600 lines of dialogue and about five unique voices, but four years later Tom

Clancy’s Ghost Recon 2 had more than 2500 lines of dialogue and more than 15

unique voices. These days, a games such as Mass Effect and Grand Theft Auto

IV have even more complex and challenging voiceovers to manage—hundreds

of characters (some voiced by celebrities), tens of thousands of lines of dialogue,

Chapter 10Chapter 10

158 THE GAME PRODUCTION HANDBOOK, 2/E

and dynamic voiceover systems so that the player doesn’t hear the exact same

voice cues over and over again.

If your game has thousands of lines of dialogue with numerous characters,

work must start months in advance to write the script, secure a recording studio,

audition actors, and record and process the voiceover files. As with all the other

aspects of game development, if these tasks are carefully planned for, the more

successful you will be during the voiceover process.

10.2 PLANNING FOR VOICEOVER

Initial planning for game voiceover needs to happen in the pre-production phase.

In this phase, the goals of the voiceover design can be defined, and any techni-

cal considerations for reaching these goals can be explored. If voiceover is an

afterthought in the development process, it is more difficult, time consuming,

and costly to implement.

One thing to keep in mind when planning for voiceover is that you want to

wait as long as possible before actually recording the final voiceover. Voiceover

dialogue will change during the course of development. For example, during

play-testing, the designer might decide that adding a line of dialogue is necessary

to make the mission objective clearer. This addition can be done more easily and

cheaply if the final dialogue has not been recorded. However, having the basic

plan outlined in advance, but not implemented, allows the team the flexibility to

look for opportunities to improve the script with such revisions most efficiently.

So even though you will not need to record the final voiceover until well after

alpha, you must have the basic plan outlined to accommodate any last-minute

voiceover changes or additions.

Voiceover Design

Voiceover is one of the primary ways to bring the game characters and story to

life for the player. For example, a good voiceover actor will be able to convey

whether a character is human or alien, and uptight or carefree. Voiceover com-

municates information about a character’s state of mind or a situation to the

player. Is the character afraid, sad, in danger, or confident? Is the voiceover

coming from a television broadcast or from another room?

Additionally, the voiceover design is the biggest determining factor of how

much it will cost to get the desired voiceover effects. The design details how

voiceover will be used in the game, how many lines of dialogue are needed,

how many characters will have spoken parts, and which dialogue will have ad-

ditional processing and effects. Usually the game designer and sound designer

VOICEOVER 159

work together on the voiceover design to make sure that it is fully thought out

and works for the game.

For example, if working on a massively multiplayer online game, the design-

ers might decide that every nonplayer character must have several hundred spo-

ken responses to different situations. If there are 100 characters in the game, the

amount of dialogue can be well over 10,000 lines, which creates a huge amount

of sound assets to record and track. After looking at the initial design and real-

izing there is not enough time or money to record this amount of dialogue, the

designers can go back and revise the voiceover design accordingly.

The voiceover design will differ for each game, with the game genre being

a major influence on some of the differences. For example, role-playing and

adventure games usually have a large cast of characters and conversations going

on between characters and, therefore, tend to have extensive dialogue. Games

that are not story driven, such as racing games and some action games, usually

have fewer speaking parts and use the dialogue to direct the player through the

gameplay space or to create atmosphere.

Technical Considerations

In addition to creative decisions about voiceover, technical decisions must be

made as well. The technical factors, such as file formats, will differ based on the

game engine being used, but there are a few general technical considerations to

keep in mind when planning for voiceover in the game.

Avoid Concatenation

Concatenation is a method where separate lines of dialogue are spliced together in

the game engine and played in the game. For example, “Hello, my name is [Character

Name]” would be created in-game by splicing together the recorded line “Hello

my name is” and another recorded line with the character’s name. Programmers

might want to use concatenation to cut down on the amount of memory needed to

find the appropriate sound asset and to reduce the amount of game assets to track.

However, concatenation is a problem for localizations, since different languages

have different grammatical rules. Additionally, concatenated dialogue is difficult to

record, because it is hard to match the voice inflections and pitch for each line of

dialogue. When the full line is played in-game, the player is likely to notice that two

files are spliced together, instead of hearing one continuous file.

Managing Assets

Whether the game includes 100 or 10,000 audio files, thought must be given to

how these assets will be tracked and managed during the development process.

The more audio files there are, the more important an audio asset management

system is. At a minimum, establish a single location in the source control database

160 THE GAME PRODUCTION HANDBOOK, 2/E

for storing the source audio assets, the voiceover script, and character descrip-

tions. This way, any changes made to the assets, scripts, or character notes are

tracked, and it ensures that everyone is working from the most current version.

If multiple versions of the script are available, you might accidentally record

from the wrong one during the final recording session. This can be a costly mis-

take, as you would likely need to re-record the correct dialogue at a later date.

Additionally, an asset management system makes it easier to determine

whether the recording studio has delivered all the necessary assets. Ideally, one

of the engineers can set up an automated process to validate the audio asset

filenames against the filenames listed in the voiceover script. If the files deliv-

ered by the recording studio are not validated and accounted for right away, you

might find yourself missing key audio files. If these missing files are not noticed

until later in the project, more costs could be incurred if you have to go back to

the recording studio for them.

If there are several speaking parts with numerous lines for each part, you

might want to consider setting up a database to track all the voiceover assets.

A database can be useful because you can sort by many different variables. For

example, 10,000 lines of dialogue could likely take several months to record. A

database can allow you to sort by the characters you want to record in a given

week or by which dialogue has been recorded and which has not.

File Naming Convention

Decide the file naming convention before recording any voiceover, even place-

holder files, for the game. If a convention is not established at the beginning,

much confusion will result if the game designer, sound designer, and recording

studio are all using different ways to refer to the files. It will be impossible to

determine what has been recorded and what hasn’t. If the placeholder voiceover

files are named the same as the final voiceover files, you can simply swap in the

final files and easily replace the placeholder files.

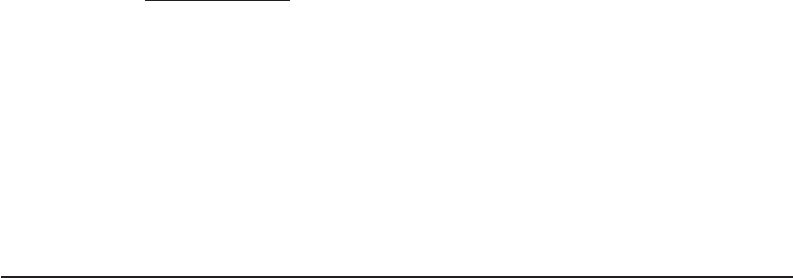

Choose a convention that will allow someone to look at the filename and

know exactly who said it and where it is located in the game. In Figure 10.1, a

file naming convention has been chosen that indicates the mission number, the

character name, and the chronological number of that character’s lines in that

section of the game.

File Formats

The source formats for audio files are usually some type of .wav or .aiff file,

which is something a recording studio can easily provide to a developer. When

the source files are delivered, an engineer can convert the audio files for use in

the game. The sound engineer creating the source audio files needs to know all

the specifications so he can deliver files with the correct bit depth, sample rate,

VOICEOVER 161

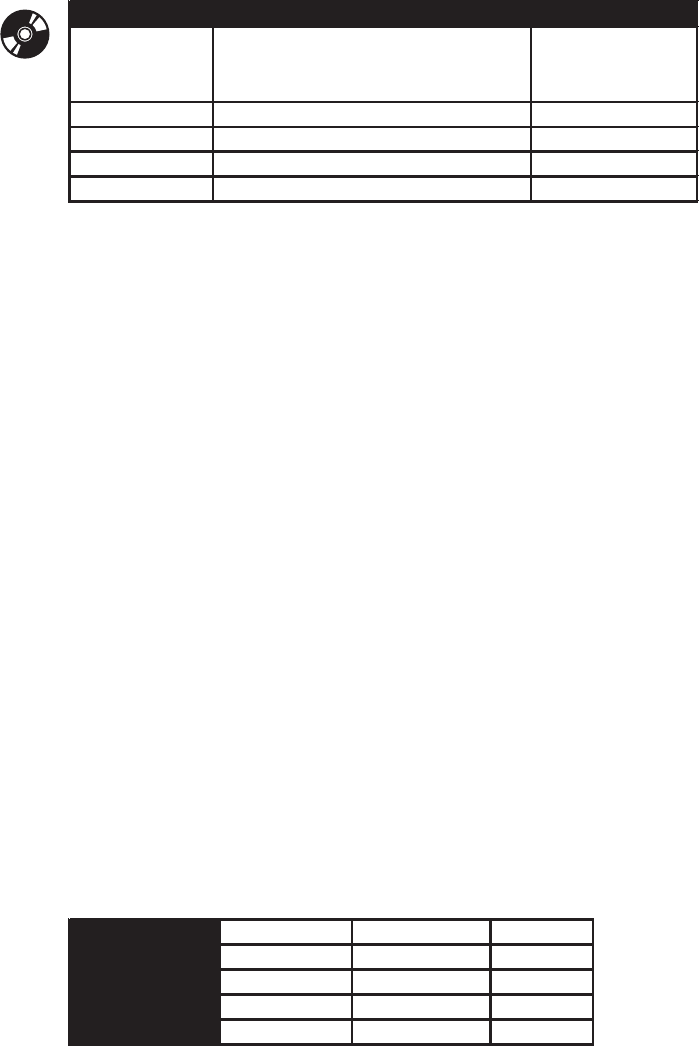

format, and target platform. Figure 10.2 lists some common sound specifications

and formats used in games.

Bit depth, also referred to as resolution, indicates how many bits are used

by a sound file in a set interval of time. Higher sound quality requires a higher

bit depth.

Sample rate is how many samples of sound are taken each second when the

sound is converted to a digital format. Higher sound quality occurs at higher

sample rates. Bit depth and sample rates work together, with common pairs

being 8 bit/22 kHz (low end audio), 16 bit/44 kHz (CD quality audio), and

24 bit/96 kHz (DVD quality audio).

Playback can refer to mono, stereo, or another type of playback. Mono indi-

cates that the sound file plays on a single channel, and stereo indicates the sound

file plays on multiple channels.

The format of the sound file is related to the file extension. WAV or WMA

formats are common file formats for PC sound files, and AIFF is the common

sound format for a Macintosh. Platform refers to either PC, Macintosh, or pro-

prietary console platforms.

The source files should be delivered uncompressed for the highest sound

quality, especially if they are going to be converted to another format for use in

the game. Uncompressed files can also be useful for sound mixes, experimenting

with different special effects, and for correcting any corrupted sound files.

However, if the source files need to be compressed, the proper compression

scheme must be used.

O

N

T

H

E

C

D

FIGURE 10.1 Example of file naming convention.

Name Dialogue Filename

Bad Guy #13 We're in the van, commander.

We're going to lose the police on

the interstate.

01_bg13_01.wav

Bulletpoint Sam, they're getting away! 01_bp_01.wav

Sam I'll cut them off. 01_sam_01.wav

Civilian #3 Help me! 01_c3_01.wav

Sam I'll call the ambulance. 01_sam_02.wav

Bit Depth

8 bits 16 bits 24 bits

Sample Rate

22 Khz 44 Khz 96 Khz

Type

Mono Stereo Stereo

Format

WAV AIFF WMA

Platform

PC Mac PC

FIGURE 10.2 Sound file specifications.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.