There are Too Many Projects to Do!

Principles for selecting projects

By having a staged approach you do not need to make all the decisions at the same time. A staged framework enables you to make the necessary choices when you have adequate information to hand, rather than being forced into premature and ill-conceived choices.

‘When you choose anything, you reject everything else.’

G K CHESTERTON

Principles for selecting projects

There are always far more ideas for projects to change a business than resources or money can support. To make matters worse, the less clear your strategy is, the more ideas there will be, thus compounding the problem.

How can you:

- make sure you undertake the projects you need to?

- limit the number of projects without stifling the good ideas?

- kill off the projects which have no place in your organisation?

- ensure that speed through the project stages is sustained?

The staged framework within which each project is managed, coupled with effective decision making and business planning, is the key to ensuring you can do all of this. By having a staged approach you do not need to make all the decisions at the same time. A staged framework enables you to make the necessary choices when you have adequate information to hand, rather than being forced into premature and ill-conceived choices. Keeping to three basic principles will help you do this:

- Do not put a lid on the creation of new ideas for projects.

- As soon as you can, make an informed decision on which projects to continue.

- Having decided to do a project, do it, but stop if circumstances change.

1 Do not put a lid on the creation of new ideas for projects

In Part Two you saw that a project should not be started unless a person stands up as needing the benefits (the project sponsor). You should encourage the creation of as many ideas as possible, letting them originate in any part of the organisation (see p. 89). Stifle creativity and you risk stifling the future growth of your organisation. The use of a targeted proposal template, such as that given on the CD-ROM should ensure that enough information is collected about an idea (or need) to enable the organisation to review and approve or reject it on the grounds of strategic fit.

The decision to start a project is taken at the Initial Investigation Gate and is only concerned with the first of the three gate questions: ‘Is there a real need for this project and, in its own right, is it likely to be viable?’ (see p. 56). Once the go ahead is given, the initial investigation should start.

A REMINDER OF THE KEY QUESTIONS

The decision points prior to the start of each stage are called gates and answer three distinct questions:

- Is there a real need for this project and, in its own right, is it viable?

- What is its priority relative to other competing projects?

- Do I have the funding to undertake the project?

If you are uncertain of your strategy, you will create more proposals than if you really understand the direction the organisation is to take. However, if a proposal passes this first gate, you know that at least one person (the project sponsor) believes the proposal does fit the strategy and should be evaluated. In this way you will benefit from knowing how your senior managers are converting their understanding of strategy into action. The aim of portfolio management is to make projects visible: the ‘outing of projects’. If a manager is undertaking projects his/her colleagues consider to be outside the needs of the business or of low priority, this will be exposed. Consider also what else such a manager may be doing which may be contrary to the direction of the business but which is invisible!

I cannot over-emphasise the impact that a clearly communicated strategy and business plan has on the effectiveness of selecting and managing your project portfolio. Part of this relates to the number of projects started and terminated.

2 As soon as you can, make an informed decision on which projects to continue

The first gate enables you to start investigating the unknowns on the project. You should know why you are undertaking the project but, on some projects, you may not know what exactly you are going to have as an output or how you will go about it. For relatively simple projects you may know both these things. The objective of the initial investigation is to reduce this uncertainty. The output of the initial investigation should provide sufficient knowledge to:

- confirm strategic fit;

- understand the possible scope and implications;

- know what you are going to do next.

In other words, you will have the information to hand which will enable you to make an informed decision on whether the project should continue, rather than one based on your own ‘feel’ and limited knowledge.

If you have only one project to do, its priority is easy to assess. It is PRIORITY ONE. If you have more than one project to review, the question of priority has no significance if you have the resources and funding to do them all when they are required. Priority only becomes an issue if you have insufficient resources to do everything you want to do, when you want to do them.

Assessing relative priority should be done on an informed basis and so cannot happen until you reach the Detailed Investigation Gate, after the output from the Initial Investigation Stage is available. Once the project sponsors have confirmed that they still need the benefits their projects will produce, you will need to concentrate on:

- the ‘doability’ of the projects;

- their fit within the overall project portfolio.

Doability takes for granted the project sponsors’ assessment of strategic fit and the soundness of each project on a stand-alone basis. It concentrates mainly on whether you have the resources and funding to undertake all the projects. If you do, a portfolio assessment is done.

The portfolio assessment looks at the balance of risk and opportunity for the proposed projects together with the current project portfolio. The aim is to assess whether this mix is in fact moving the organisation in the desired direction.

If you are unable to undertake all the desired new projects, you will need to make comparisons between them and choose which should continue. This implies that you need to batch your projects at the Detailed Investigation Gate to make this decision. In practice you will be deciding which projects should proceed, as it is projects which lead to action, but it is more powerful, from a decision-making viewpoint, to prioritise the benefits the projects produce rather than the activities the project comprises. After all, the benefits are what you need, not the projects. By prioritising benefits you will:

- stay focused on why you are doing the project;

- trap the projects which actually have no real benefit!

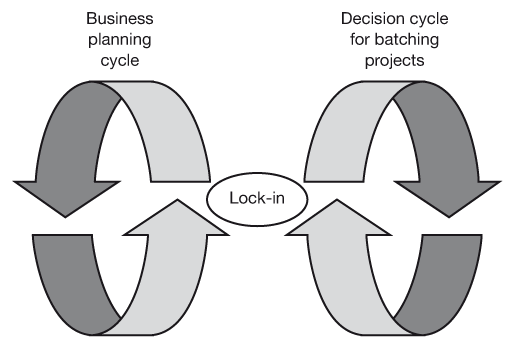

It is best if the prioritisation decision coincides with a review and reforecast of your business plan as a whole. You will be able to build whichever projects and benefits you need into the plan, while ensuring the totality of future benefits from ‘business as usual’ and projects adds up to the figures you need (Figure 15.1).

Figure 15.1 Matching the batching time frame to your business planning cycle

If the decision as to which projects should continue coincides with a review and reforecast of your business plan as a whole, you will be able to build whichever projects you need into the plan, while ensuring the totality of future benefits from ‘business as usual’ and projects adds up to the figures you need.

ENOUGH INFORMATION?

You can always avoid making decisions by saying you haven’t got enough information. It’s a very effective tactic for blocking anything you don’t want done. You will never have enough information for decision making. You need to make an assessment of what you have at stake if your decision is wrong and balance this against what you stand to gain if your decision is right. If you have a staged approach to projects, coupled with good control techniques, you will be able to ‘de-risk’ your decision making to the extent that you are answering the question, ‘Can I confidently continue with the next stage of this project?’ You very rarely find you are making life and death choices.

3 Having decided to do a project, do it – but stop it if circumstances change

Having decided to carry on with a project after the review at the Detailed Investigation Gate it is useful to presume it will continue. You, therefore, need only assess the relative merits of the new projects you wish to introduce to your project portfolio. This avoids going back over previous decisions and puts an end to the ‘stop–go’ mentality that ineffective staged processes can result in. It is a strange phenomenon that today’s ‘good ideas’ tend to look more attractive than yesterday’s! Consequently, the temptation is to ditch yesterday’s partially completed projects in favour of new ones. The result is that nothing is actually finished!

A presumption that on-going projects will continue does not mean that you should never stop a project that a project sponsor is relying on. For example, assume you have sufficient resources to do all except one new project, and this cannot be done because a key, scarce resource is already occupied on an on-going project. In such circumstances you would usually presume the ongoing project continues and the new project is delayed. The new project, however, may have considerably more leverage, resulting in greater benefit, in a shorter time, at less risk than the existing one. Hence you may take the view that it serves the overall interest of the organisation better to terminate the existing project and start the new one. Such decisions should be very rare, as, if they are not:

- your portfolio will be unstable and you will run the risk of delivering nothing of value;

- it may be symptomatic of poor business planning and a lack of clearly understood strategy.

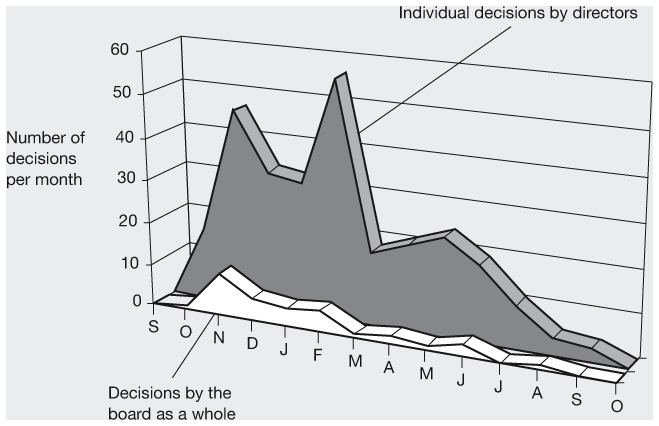

Ability to change – decision making

To what extent does the ability to devolve decision making influence how fast you can implement change? In the planning stages of a complex change programme, the project managers identified each point which required either a board decision or the decision of one of the directors. In all, about 200 decisions were identified spanning nine change projects. Figure 15.2 shows this. This begs some questions:

- Were the board members in fact capable of making that number of decisions in the timescales required, on top of all their ‘business as usual’ decisions?

- Were there any decisions which could have been delegated to relieve them of the burden? If not, what impact would the decision overload have had on the programme?

Notice the shapes of the two graphs. The board as a group has most of its decisions toward the front. As the projects get under way and alignment has been achieved, the bulk of the decisions is made by individual directors. The shape of the curve for the directors has both a front-end peak and peaks toward the back. This is because they not only approve the initial work, but also completion of the key final deliverables toward the end of each project. This does, however, also highlight a common failing of many boards: they lose interest once they have made their initial decisions!

Project authorisation

Harnessing the staged framework

The management of the full portfolio of projects relies on a basic staged project framework being in place. To ensure speed through the project stages you should minimise referral to any decision-making bodies outside the project team. Inefficient decision making at gates can double a project’s timescale. Nevertheless, you must have sufficient referrals, at appropriate points, to ensure that the portfolio is under control, is stable and is likely to meet your needs.

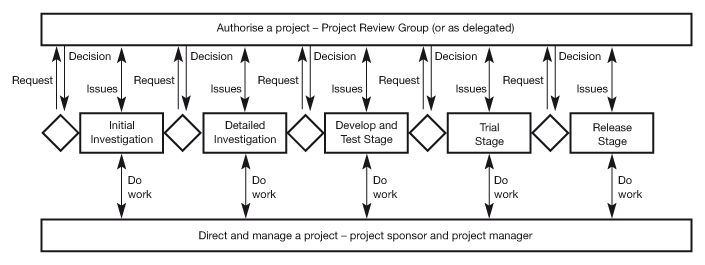

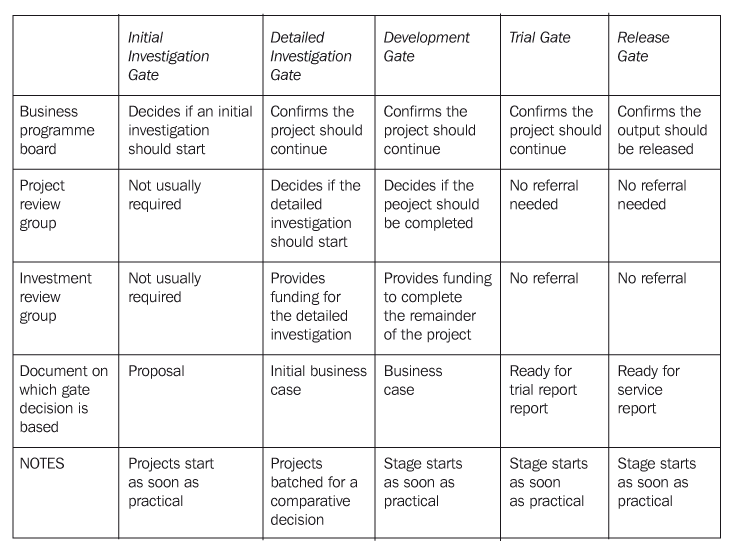

Referrals from the project organisation to the portfolio management organisation usually happens at the gates (Figure 15.3). Thus:

- the management of a project is concerned with the work within the stages leading up to a gate decision;

- the management of the portfolio is concerned with ensuring decisions are made at the gates.

Figure 15.3 Interaction between managing a project and managing the portfolio

Referrals from the project to the ‘authorisation process’ happen primarily at the gates. Where a problem (issue) on a project requires a change, a referral may be made during the course of a stage. In this diagram, the project review group is shown as the authorising body; for large organisations, there is likely to be some delegation, say to the Business Programme Manager.

Where an issue on a project requires a change, a referral may be made from project management to portfolio management during the course of a stage.

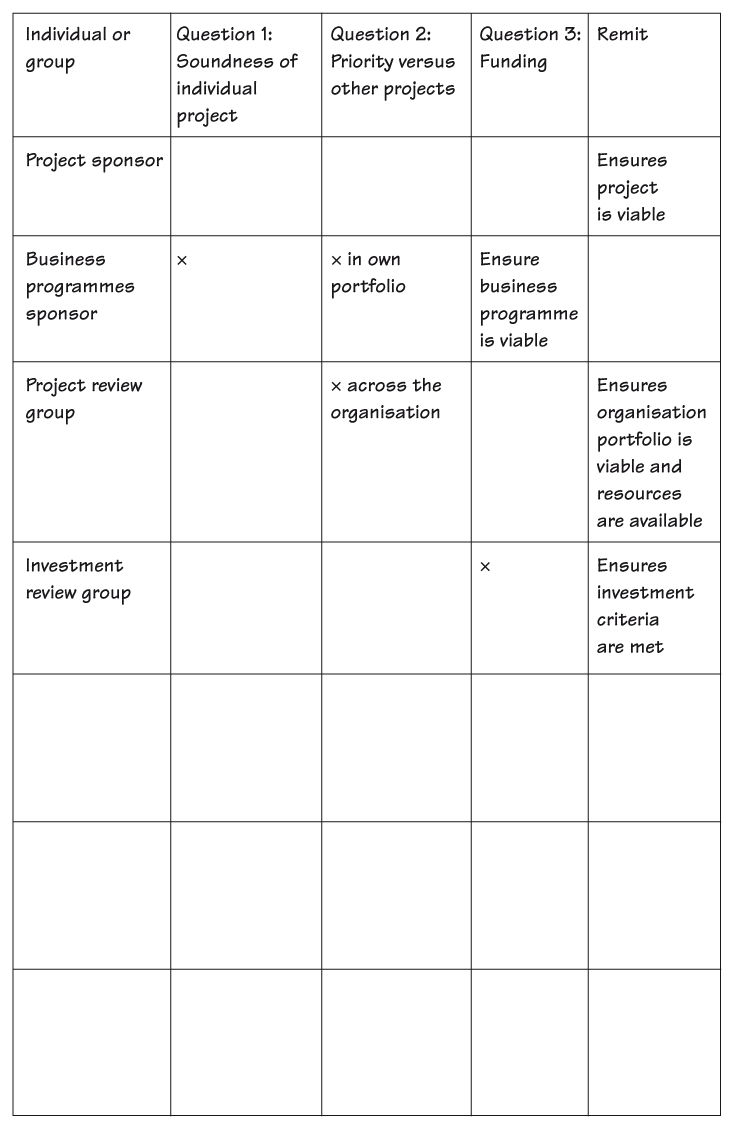

The choice of who contributes to the decisions is crucial. Earlier (pp. 56, 180) we saw that the decision is the culmination of three distinct questions. The roles relating to these are as follows:

- The project sponsor answers the gate question 1 – is there a real need for this project and, in its own right, is it viable? The project sponsor is the person who requires the benefits the project will realise and who assesses its fit to strategy.

- The project review group answers the gate question 2 – what is the priority? It assesses the ‘doability’ and integrity of the portfolio as a whole. (The typical activities which this group undertake are given on p. 188.)

- The investment review group answers gate question 3 – do we have the funding? It ensures that the financial ‘rules’ are applied, that the project makes sound business sense and that funds are available to do it.

I have shown the roles of the investment review group and the project review group separately. In practice it is better, but not essential, if the roles are combined into a single body. Note that both these titles are used to illustrate a role required in the governance of projects; what you choose to call them is your choice – there are no commonly accepted terms. Also, you may choose to combine a number of roles in a single body.

Gate decisions

Assuming that the project, on its own, makes sound business sense, what else does the project review group need to know about a project or investment before it can commit the organisation to it?

- What are the project’s overall business objectives?

- On what projects does this project depend?

- What projects depend on this project?

- When will we have the resources to carry out the project (people and facilities)?

- Do we have enough cash to fund the project?

- Can the organisation accept this change on top of everything else we are doing?

- After what time will the project cease to be viable?

- How big is the overall risk of the portfolio with and without this project?

1 ROLE OF PROJECT REVIEW GROUP

A cross-functional (or cross-process) group of decision makers for authorisation, prioritisation, issues escalation and resource allocation. Its primary aim is to keep the pipeline of projects flowing. As such the project review group is the gate keeper for all the project framework gates and accountable as owner of the authorisation process.

2 AIM OF PROJECT REVIEW GROUP

The project review group exists to manage and communicate the authorisation, prioritisation, planning and pre-launch implementation planning for business change projects.

This includes ensuring that fully resourced and committed plans for projects are created and aligned within the organisation’s rolling forecast and each has a viable business case.

3 ACCOUNTABILITIES

The accountabilities of the group are:

- to authorise projects and oversee any delegation of such authority;

- to ensure that the portfolio can be delivered within existing funding allocations by ensuring the organisation’s business plan reflects the projects within the portfolio;

- to ensure each project is locked in and committed to by those required to develop it and operate the outputs post-release;

- to identify options for resolution of issues involving resources and escalate for resolution if appropriate;

- to ensure that functions have planned in ‘white space’ resources to undertake initial investigations (see Chapter 16);

- to communicate/publish the current status of the organisation‘s portfolio;

- to act as the change control point for the organisation’s portfolio;

- to be the owner of the authorisation process.

Each gate in the project framework is described, from the perspective of decision making, in the following sections.

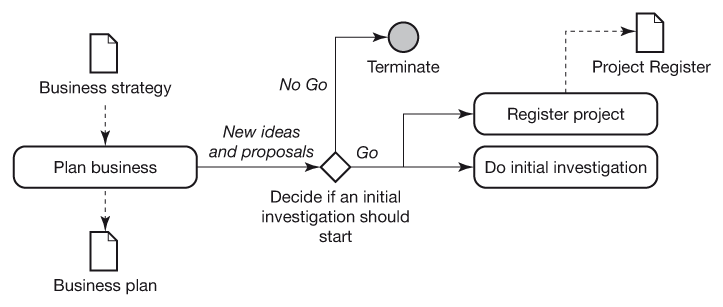

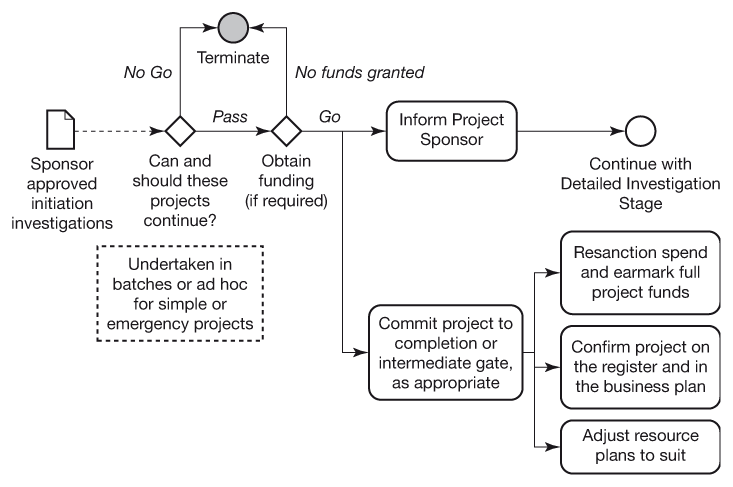

Figure 15.4 Decision process at the Initial Investigation Gate

Any idea that the business programme sponsor wishes to study further should be investigated without delay.

Initial Investigation Gate

While all gates are held by the project review group, this first one is often delegated to a Business Programme Sponsor or Manager. Any proposal which they believe is worthy of further study should pass into the Initial Investigation Stage without undue delay (Figure 15.4). Some organisations have a special group to review proposals and take decisions on which should proceed. However, an effective business planning process should make such a group unnecessary. In most cases, except for extreme reactions to market or business conditions, the business plan should spawn the proposals, hence they will have effectively already been ‘approved’, at least in outline.

Detailed Investigation Gate

Assuming each project has been approved by the project sponsor, the candidate projects are batched and an informed choice is made as to which should be authorised to proceed into detailed investigation (Figure 15.5). Two basic questions need to be asked by the project review group:

- Is it likely that all these projects can be completed?

- If we include them all, is the portfolio balanced?

Figure 15.5 Decision process at the Detailed Investigation Gate

Decide which out of a number of projects can, and should, continue to the next stage.

If the answer to both these questions is ‘yes’, and there is sufficient funding, the full batch of projects proceeds into the Detailed Investigation Stage. If, however, all the projects cannot be done, then those in contention are compared and a decision is made as to which of them should proceed. Alternatively the constraint may be identified and, if possible, released (e.g. by delaying a project or applying new resources).

It should be your intention that any project which is allowed past this gate is going to move to completion unless it loses its viability or becomes unacceptably risky. For this reason you can think of this as the NO gate, i.e. where the business says ‘No, we will not consider that project further’.

A project in which confidence to complete it is relatively high and which is committed to completion need not be referred back to the project review group unless it hits an issue which requires a reassessment of the project viability and resourcing. The ‘simple’ projects referred to in Chapter 12 are an example of this. In other instances, however, the project review group will not have sufficient information to commit a project to completion. In which case, the project will be committed only as far as the Development Gate, when another assessment is done.

Once agreed by the project review group, the investment review group should provide funding to complete either the project or at least the Detailed Investigation Stage and the project costs, benefits and resource needs should be locked into the business plan. In some organisations the project review group and investment review group may be one and the same.

THE CAPACITY OF THE TOTAL SYSTEM IS THE CAPACITY OF THE BOTTLENECK

When the project review group assesses whether a project can be done, it must satisfy itself that ALL aspects can be done: operational, technical, marketing, process, etc. If one part is missing, then there is little point in doing any of the other work. Your ability to complete projects is, therefore, constrained by the bottlenecks imposed by scarce resources for a particular aspect of work. By undertaking a formal ‘doability’ check, you will quickly identify any constraints and also be able to assess the cost to the organisation of missing or insufficient resource. This cost is the sum of the benefits from the projects you could not do because that resource was not available. This simple concept is the basis for what is called Critical Chain in Eli Goldratt’s Theory of Constraints.1

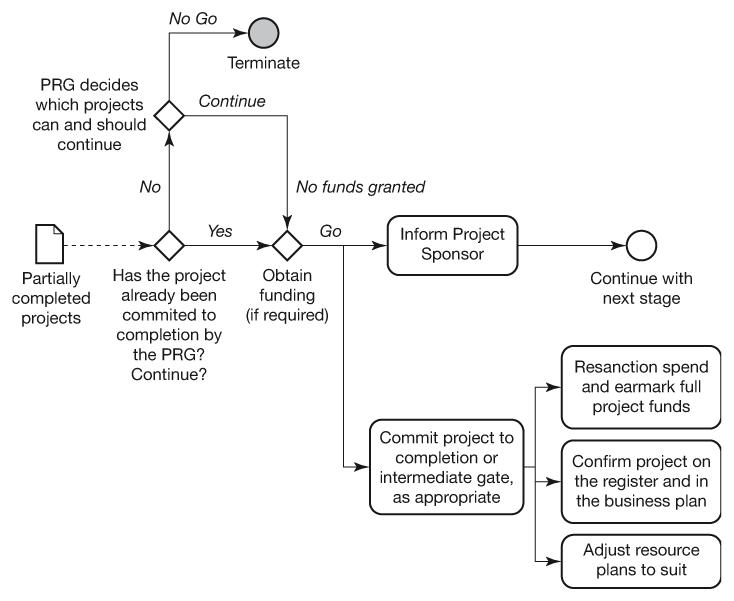

Development Gate

At the Development Gate, the project review group is only concerned with those projects it could not previously commit to completion. Again, the same questions are asked at the Detailed Investigation Gate. In principle, any project which has reached this gate is one which the organisation wants to continue. Forward planning should have earmarked the resources required to complete the project. As the presumption is to continue the project unless circumstances dictate otherwise, what is looked for here is confirmation that the project can continue. For this reason, the Development Gate should be considered as the YES gate. The investment review group provides funding to complete the project if this had not been given earlier. The business plan is amended to incorporate changes to costs, benefits and resource needs resulting from the detailed investigation. The process is shown in Figure 15.6.

Figure 15.6 Decision process after the Detailed Investigation Gate

If the project has already been committed for completion and is still within the scope, timescale and cost approved at the detailed Investigation Gate, no referral to the project review group is needed. The project just continues, obtaining extra funding, if not already allocated. For all other projects, the project review group needs to confirm it within the project portfolio.

Trial Gate

The project sponsor is often delegated accountability for approving the move into trial. This is based on advice given by the project manager and team and is based on a ready for trial report. The project sponsor holds the decision as it is he/she who requires the benefits. Trials are often the first time a change is presented to the outside world and it is in the interests of the sponsor to ensure that a premature presentation does not compromise downstream benefits. The project review group needs to be consulted only if there are any prioritisation issues. In such cases, the process in Figure 15.6 is followed.

Release Gate

Again, this is primarily a project sponsor decision. As with a trial, the sponsor does not want the benefits jeopardised by releasing the project output before everything is ready. Alternatively, depending on the scale of impact of the change, this decision could be made by a business programme board, project board, or even a management board. The project review group only needs to be consulted if there are any prioritisation or resource issues or if this gate decision has been explicitly retained by them. In such cases, the process in Figure 15.6 is followed.

Summary of decision-making roles at each gate

The following table summarises the decisions at the gates and who is involved. In the case of this table, a business programme board may delegate the decision to a project board or to the project sponsor. Consider this table as a starting point for you to assess the appropriate decision-making bodies and levels in your organisation. Remember, as the project definition document contains a list of deliverables and who has approval accountability (see p. 300), you are able to choose the most appropriate people or groups for each project on a case-by-case basis if your ‘usual rules’ are not appropriate.

Batching projects

Earlier (p.181) I said that you would need to batch potential projects at the Detailed Investigation Gate so that you can make an informed decision regarding which should continue. If you do not have batching, prioritisation can become meaningless. Projects are likely to be allocated resources on a first come, first served basis rather than on a ‘biggest win for the organisation’ basis. Batching, however, begs two questions:

- How frequently should I do the batching?

- Won’t this slow down the projects by introducing a pause?

As far as frequency is concerned, you need to select a time period which enables a reasonable number of initial business cases to be drawn up and to be compared with one another while not introducing too long a delay:

- Annual batching would be too infrequent. The business environment would have changed so much in that time that the exercise would be futile.

- Weekly may be too frequent. There would be an insufficient number of projects to allow meaningful decisions to be made.

- Between a month and a quarter is probably about right.

As for slowing projects down, the answer is no. Batching should not usually slow anything down. Unless there is spare resource available to undertake the project immediately, nothing can happen. Consider also that there is no point in rushing ahead with a project if it is the wrong one! Nevertheless, there will be cases where delaying a project to allow batching to occur is not in the best business interests. These cases are for:

- ‘simple’ projects;

- emergencies;

- exceptions.

Simple projects were discussed in Part Two (p. 136). They are projects where you can see clearly to the end by the time you have completed the initial investigation. They also tend to consume few resources and little money. In such cases, the project review group allows the project to proceed into detailed investigation without delay, as the chances of the project compromising future ‘better projects’ are very slim. A project may be thought of as ‘simple’ by the project manager, but it is the project review group who actually decides this. I would also argue that defining, in quantitative terms, what constitutes ‘simple’ may be a time-consuming and difficult exercise. Further, once you have defined it, you may find that project sponsors and managers massage their initial business cases to fall within your defined threshold and thus ensure their projects go through without delay. This is not the behaviour you should encourage. It is more pragmatic to phrase the definition of ‘simple’ in terms of principles and allow the project review group to exercise its own discretion. After all, it should be made up of responsible managers and not merely administrators of predefined ‘rules’.

Emergencies are another exception to batching. I define an emergency as a project which, if delayed, would severely damage the organisation. An emergency is not a ‘panic’ as a result of poor management in a particular part of the organisation. Unlike simple projects, emergencies may need to displace resources from on-going projects, thereby causing earlier commitments to be broken. If they aren’t true emergencies, you will simply be moving the problem from one part of the organisation to another. As these projects can have a disruptive effect, the approval for them at the Detailed Investigation Gate should rest with top management (e.g. board), following a detailed impact assessment by the project review group.

GIVING UP SOME PERSONAL POWER?

Who has the authority to commit resources:

- in a department in your organisation?

- in a function within your organisation?

- anywhere within your organisation?

- in another, supplier organisation?

Treat the word ‘organisation’ as independent operating division if you are in a global organisation. The answers to these questions will probably be, respectively, the head of department, the head of function (often a director or vice president title), the CEO or chief operating officer, and someone in that other organisation. In other words, the power to apply and commit resources usually lies within the functional or line management hierarchy. If this is the case and organisations need to draw on resources from anywhere to undertake projects, there is only one person (maybe two people) in the organisation empowered to do this: the CEO and COO (if you have one). No person, no matter what their title is, has the authority to commit resources which are outside their domains. Unless an organisation has alternative structures to make cross-functional commitments, the top people will become overloaded with operational issues. Hence the need for a cross-organisation decision-making body such as a project review group. In effect, the owners of the resources are giving up part of their power to a cross-functional decision-making body and it therefore also holds that they should respect the decisions of that group and not unilaterally withdraw resources for their own departmental or functional needs. If the lines of communication work and their person on the group plays their part, this should pose no problems.

Exceptions are any other type of project, other than emergency or simple project, that you wish to continue without going through a batching process. In other words, a pragmatic, but open and deliberate, decision, within the principles of business-led project management, which you deem to be in the organisation’s interest. It is pointless to dream up possible scenarios and rules for these. It’s a waste of time. Just deal with them as they arise. By definition, exceptions are ‘exceptional’ and rare.

Beyond batching

The whole reason for batching is for you to decide, from among many contenders, which projects are the ‘right’ ones to take on. By insisting on a named project sponsor, you are obtaining an unequivocal statement that at least one senior manager believes the project is the right project. By having a project review group, you are making a decision body accountable for ensuring the resource is available and that the mix of projects within the portfolio is the right mix. Poor business planning will make the jobs of the project sponsor and project review group more difficult. Conversely, good business planning will make it far easier. Add good information on the current and future commitment of resources and expected benefits and the project review group’s task simplifies further. Good business planning will spawn the right proposals, which in turn spawn the right projects. This being the case, batching may become less necessary. If you have a view of what is in the project pipeline, ready to arrive at the Detailed Investigation Gate, you will be able to allow more projects to proceed between batches without compromising future projects. Consultants and contractors do this all the time; can they wait and batch up which bids they would like to respond to? No, they have to take a view on their workload, assess the likelihood of success, the availability of resources and the impact on them if they succeed. They then make a choice either to bid or not bid. (Remember which organisations were found to have the best resource management systems? See Part One.)

Issues requiring a high level decision

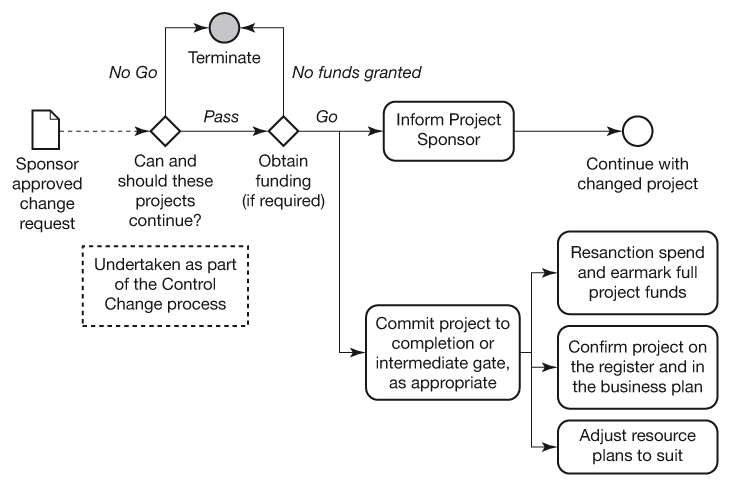

Not all projects will go according to plan. There will be instances when changes to a project as defined and approved are desirable. Unless this is managed, scope, timescales and costs will creep and the project ‘pipeline’ will become blocked. There will be too much work to do and not enough people or cash to do it. Small changes can be dealt with either by the project manager or project sponsor. However, where a proposed change has an impact on other commitments the impact must be assessed and the approval of the project review group obtained. Chapter 25 describes the change process fully from a project manager’s and sponsor’s viewpoint. The process for handling escalated changes is very similar to that for the gate decisions described earlier. It is just that the need for the decision is driven by unexpected events rather than by reaching a predictable milestone (Figure 15.7).

The proposed change is reviewed by the project review group and, if it can be accommodated within the portfolio, approval is given to proceed. Authorisation for any extra funding should also be given, if required. In some cases, the project review group may choose to alter the relative priorities of projects if there are resources or funding constraints. See Chapter 25 for a full treatment of ‘change control’.

Selecting the right projects

Project selection and business planning

Why do so many enterprises:

- waste scarce funds and resources on worthless projects;

- have little understanding of what benefits will accrue from their project portfolios;

- struggle interminably with the annual budget setting and decision process?

Research by the GenSight Group2 suggests between 35 and 50 per cent of all investment is directed to unsuccessful projects and that about 30 per cent of project investment by FTSE 100 organisations in 2000 actually destroyed shareholder value!

The demand for improved returns from project investment is now pervasive, from public and private sectors alike, yet most organisations still struggle with the process of deciding what projects to do as well as when to do them. Portfolio management is a discipline that can increase significantly the value derived from project investments. The concepts have been established for 50 years in the financial investment community and are now starting to be applied to planning portfolios of projects.

Portfolio management is an activity that aligns a portfolio of projects to the strategy of the organisation. As such, it is an integral part of business planning. It should enable an organisation to select those projects which will create the greatest value, whilst at the same time:

- ensure strategic balance;

- handle risk explicitly;

- keep within resource and funding constraints;

- respect any dependencies between the selected projects.

In demanding times, this is something all enterprises should be seeking to do, yet it is rarely applied effectively, despite reliable methods now being available.

‘The cancellation rate of [IT] projects exceeds the default rate of the worst junk bonds – yet bonds have lots of portfolio management applied to them. [IT] investments are huge and risky. It’s time we do this.’

DOUGLAS HUBBARD, HUBBARD DECISION RESEARCH

When creating the next year’s business plan, most organisations extrapolate from the previous year’s expenditure, adjusting it for changed circumstances, with some superficial analysis of priorities. This is usually done within the organisation’s functional ‘silos’. The focus is generally upon keeping within a top-down defined budget, often with capital and operational (revenue) expenditure dealt with in different, unrelated streams. Sometimes, consideration is given to resource constraints and the level of change the organisation can cope with. This approach may work, to a limited extent, for steady-state bureaucracies but not for organisations undergoing substantial change. For these, the results are dubious, with little objective attention to:

- the relationship between capital and operational expenditure, which may be unknown or ignored;

- the impact budget cuts can have on benefit realisation, which is usually not understood;

- priorities, which are often contentious;

- the point at which projects must be rejected, which can be nearly impossible to determine;

- resource constraints and project relationships, which are often seen as too complex.

This scepticism regarding the value of some organisation’s business planning methods can also apply to outside observers. An analyst at Prudential-Bache said of a FTSE 100 organisation in which top-down cuts had been imposed: ‘Our provisional conclusion is that the current management have finally prescribed strong medicine. It remains to be seen how much life remains in the patient.’ Not very comforting!

Choosing how to decide between competing projects can cause a great deal of concern. Five methods I have seen used are outlined below:

- Executive decision;

- Financial return (discounted cash flow);

- Scoring;

- Visualisation;

- Optimisation.

I would, however, point out that none of the methods are foolproof; you cannot make a process of decision making, you can only make a process for the flow of the information required to make decisions. At the end of the day, decisions come down to a choice made by a person or group and not by a process or a clever business model. Nevertheless, there are approaches which can help significantly to improve the quality, objectivity and transparency of the decisions.

Executive decision

Just choose, based on the information and opinions you have to hand. This is a simple and often effective method, especially if you do not have to justify your decisions! Sometimes, decisions are so marginal, it doesn’t really matter what you decide as long as you make a decision!

Financial return

Investment appraisal methods based on discounted cash flow are now commonly used in many organisations to justify projects. In these they seek to either maximise the net present value and/or increase the internal rate of return (IRR). In addition, the ‘pay-back period’ can also have an influence. For example, some organisations will insist that a project returns at least 15 per cent IRR and has a pay-back period of less than two years. The IRR hurdle rate is set to capture projects with returns greater than that required by the market and the pay-back period is set to control cash flow and ensure the benefits stream is not too distant. Different organisations will set different hurdle rates. Those which have very short product life cycles tend to set short pay-back periods and higher IRR targets. You will find more on this in Chapter 22, Managing the Finances.

Making the numbers up?

In one organisation I worked with we noticed that all the projects coming up for either authorisation or selection into the business plan had internal rates of return in the hundreds or even thousands; this organisation should be enormously profitable! Unfortunately, that was not our experience. Despite these ‘excellent projects’ and more than adequate operational performance, the organisation lost money. We found two things were happening:

- the investment appraisals were ‘doctored’ so that they gave a far better impression than was the case. Optimism was rife, with ‘making the numbers up’ being the acceptable approach.

- different projects claimed the same chunk of benefit, resulting in that benefit being double counted (or sometimes counted up to seven times!).

These symptoms are classic in organisations which have poor business planning capabilities and where project selection and portfolio management are divorced from whatever business plan does exist. They are often unduly influenced by the finance function, with project selection and authorisation being perceived by the business leaders as ‘bureaucracy getting in the way of what I want to do’.

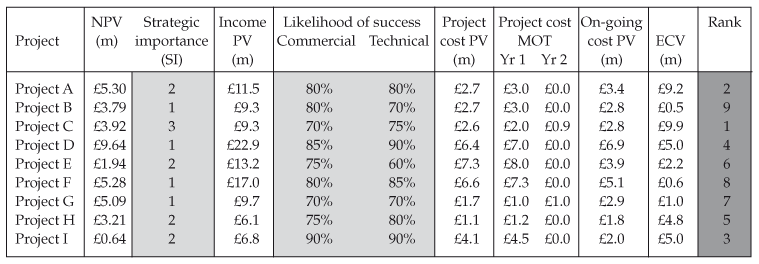

Scoring techniques

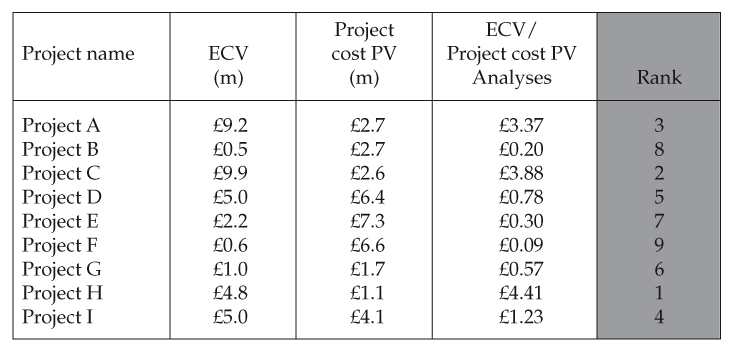

Scoring techniques seek to maximise the value of a portfolio of projects. They build on the discounted cash flow method described above, taking into account factors such as net present value, probability of technical success, probability of commercial success, the project cost and the ongoing cost of operating whatever the outputs from the project are. From these, you can calculate the expected commercial value and then rank the projects according to those with the highest value, ultimately selecting all those that were possible, within the limited budget. Figure 15.8a is a simple example for nine projects (in reality you may have tens or hundreds of projects). If you had a Year 1 annual constraint of a £20m spend, you would select the five projects with the highest commercial value: C, A, I, D and H. This would use £17.7m of the available budget.

The use of the ‘strategic importance score’ demonstrates how you can use scoring to favour projects with particular characteristics (in this case, link to strategy). Some organisations use a scoring model to take into account a wide number of factors, each of which may be weighted. It can become very complex and subjective and for this reason alone some senior managers can become sceptical!

A modification of the above is to determine the ranking, by dividing the expected commercial value by the constraining factor. In this way you can favour those projects, which give the greatest return for whatever your limited resource is. Hence this is often referred to as the ‘most bangs for the bucks’ approach! Once the projects have been ranked, keep selecting projects, in rank order, until your constraining resource is exhausted. In the example in Figure 15.8b, I have used the development cost as the constraining resource.

This approach favours projects with certain characteristics: those that are closer to launch, those which have relatively little left to be spent on them, those with a higher likelihood of success and those which use less of the scarce or constraining resource. It also requires financial or other quantitative data. This can be particularly problematic in the early stages of a project. Probabilities can be somewhat difficult to determine. None of the scoring techniques take account of portfolio balance.

Figure 15.8a – Scoring – maximising economic value

ECV = (I x SI x Cp – OC) x Tp – C

ECV = Expected commercial value

SI = Strategic importance score

OC = Present value of on-going costs

Tp = Likelihood of technical success

I = Present value of income stream

Cp = Likelihood of commercial success

C = Present value of project costs.

Figure 15.8b ‘More bangs for the bucks’ selection

Divide the Expected commercial value by the limiting resource, in this case Project cost, to determine which projects make best use of that resource. Then select those which make greatest use until the constraint is met. This results in the selection of six projects: H, C, A, I, D, and G, slightly more than the pure ‘economic value’ method in Figure 15.8a, and using £18.7m of the £20m budget.

Visualisation techniques

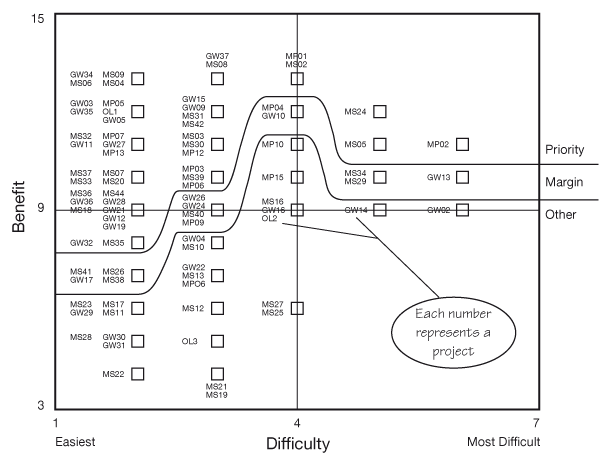

Visualisation techniques build on scoring methods but present the output in such a way that the decision maker can gain a better understanding of the non-financial factors. This is done by plotting each project on a matrix with axes representing key decision influencing factors (for example, benefit versus risk) and choosing those which are in the ‘less risky, most beneficial’ quartile (Figure 15.9). They are called ‘bubble diagrams’. The limitations of this method are that you can only have two dimensions, one represented by each axis. A third dimension is often added by using the size of the ‘bubble’ to indicate a factor such as project size. To use more dimensions you have to invent creative formulae for weighting a collection of factors into a single one. It is, however, relatively simple and can help you analyse a potentially complex set of projects. It also gives a very concise view of portfolio balance. Its output can, on the other hand, be very misleading and, as a minimum, basic management sense should be used to verify the model. In addition, it may tend to favour supposedly strategic projects over those which will yield a real financial return or vice versa, and this can lead to an unbalanced portfolio.

Figure 15.9 Example of using a matrix to aid the selection of projects

Each project is plotted on a matrix with axes representing key decision-influencing factors; in the example shown, this is benefit versus risk. Those projects which are in the ‘less risky, most benefit’ quartile (top left) were chosen for priority review.

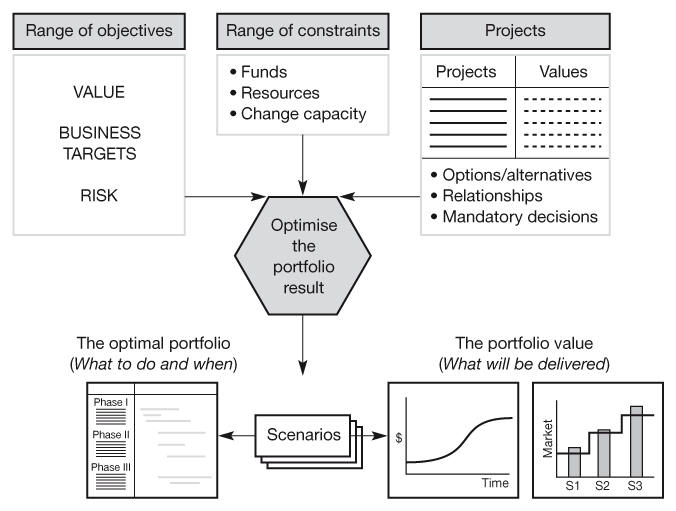

Balanced optimisation

Some organisations now use portfolio optimisation concepts, with computerised models applied if the analysis becomes complex. In these, the business objectives are stated in quantitative terms, usually a mix between financial figures and quality of service indicators. The candidate projects are fed into the model together with constraints, such as capital and resources, and the computer application derives an ‘optimum’ project mix to meet whatever targets are prescribed. This becomes effectively a scenario, as the objectives, funding or resource amounts can be easily changed to generate further possible mixes. In addition ‘essential projects’ and dependencies can also be incorporated (Figure 15.10).

Such approaches have the valuable added advantage that the timing of the projects can be considered. Hence a project may be chosen to start in one or two periods to fit within any of the constraints, without it actually being rejected outright because it cannot be scheduled in immediately.

Figure 15.10 Balanced optimisation

A range of business objectives, constraints and a set of candidate projects are used as the data to create a number of scenarios. The objective is to use optimisation to help identify which group of projects and timings takes you closest to your objectives, whilst taking into account other factors, such as risk.

The output from such models can be very enlightening and can stimulate some extremely productive discussion. This, on its own, can improve the quality of the final decision. Of interest, the model I saw also had a constraint called ‘chief executive’s project’. This allowed any project to be forced into the programme. An alternative scenario could then be to have the same project excluded, with judgment then made as to the effect of doing this project on the whole portfolio. Portfolio optimisation is more informative than the previous methods but does require specialised knowledge to construct – there are some commercial offerings which do not result in the right outputs, so beware! Senior management also need to have faith in the comparative business cases and performance indicators between the constituent projects. Mind you, if they do not trust the basic data, no rational method will satisfy them!

An organisation found that its pipeline of development projects was blocked. There were too many projects (about 120) being undertaken and very few were actually being completed. The organisation set up an exercise to get these on-going projects under control. First, each project was aligned to a staged framework (similar to that in Part Two) and then ranked on a matrix, based on difficulty versus benefit (Figure 15.9). The objective was to include the least difficult projects which gave the most benefit and which were almost complete into the portfolio. The remainder would be stopped. The exercise was not without difficulties but it did result in a smaller and more focused portfolio of projects. The matrix selection method used was known to be imperfect as it favoured short-term revenue-generating projects over longer term strategic projects. However, it was considered adequate for the task required but something better would be needed later, when they would be adding new projects to the portfolio. They agonised over the type of tool they would use when the next batch of projects needed to be prioritised. As it turned out, they did not need to prioritise for six months. The project managers, during the initial investigations, had already identified potential blockages and changed the approach and scope of their projects to circumvent them. The project review group was able to let all new projects continue. Twelve months on and no tool had yet been devised. However, the portfolio was still under control and projects were being completed at the rate of two to three a week.

Is portfolio management worth doing better?

Of course it is! Returning to Figure 1.1, there is no point in becoming really great at the art of project management and then doing all the wrong projects. Business-led project management is about both aspects and they should be indivisible. In the sections above I have very much drawn out the pitfalls relating to the different techniques. Don’t let that put you off; just use this as knowledge so you can approach the problem with your eyes ‘wide open’. Even a technically or academically poor selection process is more value than none, simply because of the debate it will create amongst the senior team. If they are talking about this topic, you are half way there.

If in doubt, think of the improvements that others have realised:

- in one organisation the overall return through optimising a project portfolio was a massive 15 per cent increase in the total estimated return;

- research has shown a potential advantage of 19 per cent in average growth and 67 per cent in profit for those achieving excellence in portfolio management (see Chapter 28 for more on this).

Benefits on this scale can never be attained by a finance-led slash and burn, cost cutting approach to business planning. It would seem the rewards are there for those organisations which rise to the challenge.

Perhaps what remains is an issue of credibility. How can senior executives become confident that some approaches are practical and can be used to turn what they perceive as ‘theoretical benefits’ into bottom line results? Some areas of management practice are now evolving, which if combined, can lead to a far more effective result. These include:

- benefits estimation;

- balanced optimisation;

- decision support.

Estimating benefits can be made more accurate

It is now common for organisations to require an estimate of benefits to justify any project investments. Major economic crisis such as the credit crunch in 2008 and the collapse of the dot-com bubble in 2000 have emphasised this trend. No longer is it acceptable to state simplistically that the latest technology or general improvements in service quality are reason enough for investment. We must now quantify the business benefit from the technology or the actual level of service quality that will result and if customers will want to pay for it.

Improved market intelligence, combined with benchmarking and multi-discipline team working, can support much better estimates of benefits. If the enterprise itself makes the effort to lay out this intelligence, with clear analysis of current performance, the sponsors of projects can prepare better estimates and save time whilst doing so.

Balanced optimisation will be more effective

The scorecard prioritisation approach outlined earlier in this chapter is often accepted as the only form of analysis available. Yet this is not the case. Balanced optimisation, using mathematical techniques, can perform the analysis more comprehensively, faster and with a closer representation of real-world complexities.

Experience now shows that not only is such analysis possible, it can also be trusted. It does not replace management judgment but rather supports it by enabling the complex factors of benefits, risks, relationships and constraints to be analysed and drawn together, enabling senior executives to apply their judgment from a far better starting point than other methods yield.

Executive decision making can be better supported

The meetings when project selection decisions are made can be better managed, to take advantage of improved data and analysis. Strategy setting sessions are often carefully orchestrated, with extensive intelligence provided to assess current performance and evolving business trends. Scenario analyses are usually built in. A similar approach can and should be taken for portfolio decision making.

Portfolio management is moving more to a process repeated at regular intervals, rather than an annual budgeting and lobbying round. To support this, those who facilitate the function can design the sequence in which performance, supply and demand are considered to lead to more rational decisions. Technology can be introduced to enable the evaluation of scenarios and options.

In summary

Business planning is serious; without it you have very little basis on which to select your projects. Project selection is the primary influence on the future direction of your business. The projects represent the changes in direction, without which tomorrow will merely be a poorer version of today and, as such, are integral to the business plan and not an ‘added extra’.

The popular finance based tools tend to give poorer results on their own than when combined with other tools. The other tools bring the strategic imperative to the fore and help achieve balance and take into account risk. When embarking on this, the scoring methods are an easy entry point, but, in my opinion, balanced optimisation is where we should be aiming; it uses the same data as scoring models but gives far richer and more useful results.

The commercial director of an engineering organisation interrupted the chief executive asking him what colour the new chauffeur cars should be. The chief executive picked up the phone and asked his personal assistant to come in.

‘What colour should our new cars be?’ he asked.

‘Red,’ the personal assistant replied.

‘There, you have your answer,’ the commercial director was told. After the commercial director had left the room, the chief executive commented, ‘I like easy decisions which I can make quickly – it makes me feel good. But that was ridiculous!’

The cars were delivered in bright red, BUT the organisation’s brand colours were blue and white!

15.1 DECISION-MAKING BODIES

This workout is for you to investigate who contributes to and makes decisions regarding your business projects and when.

- Identify all the individuals or groups in your organisation that contribute to and make decisions regarding your organisation’s projects. List them on the left of a flip chart or white board.

- Show what decisions these each make, e.g. I have shown the decision-making bodies proposed in this chapter.

- Consider and discuss:

- Are all three questions (p. 180) represented in your organisation?

- Are the accountabilities on p. 188 covered?

- Has each individual or body the authority to make the decisions?

- Is sufficient information available to those involved?

- Is question 2 considered ‘cross-functionally’? If not, consider what effect this has on projects which require resources from a number of different functions.

- Finally, decide who is accountable. Remember, accountability cannot be shared (see p. 286).

Far too many projects!

So far I have concentrated on decision making on projects where the resources are the limiting factor. This is not always the case. It may be that decision making itself becomes more critical. I have already explained how a project review group can work to ensure that you commit to undertaking only those projects you have the capacity and capability to implement. There may, however, be too many of these for a single group to deal with, so, while you may have the capacity to implement them, you may lack the capacity to decide! The first case study (see p. 184) in this chapter is an example of this.

In the benchmarking study we noted that organisations have some resources which are shared and some which are separate (see p. 27). The former led to greater flexibility, while the latter led to easier, more discrete decision making. If you have separate resources, you can have a dedicated project review group. You will need to rely on business planning to check that the level of resource applied is in line with strategy as it will not be easy to reallocate these people. Where there is shared resource, you have greater difficulty. How can you divide the project review group into a number of subsidiary parts, capable of handling the volume of projects you have? The options for this include:

- by business area (function);

- by target market plus ‘corporate’;

- by driver.

If you choose to make decisions based on function, you will fall straight back into the trap of encouraging function-based projects, working in isolation. This is not a rational choice if you want a benefits-driven, cross-functional approach. Reject this option!

You could choose to have the project review groups based on your target markets. This has the advantage that you align projects to your customers’ needs. Further, if there is little sharing of projects between segments, a logical division would be apparent. You would need to have a ‘corporate’ project review group to deal with those projects which did not sit within any particular segment.

Another way is by driver. You categorise your projects by those which are directly related to:

- the service or products you offer;

- increasing your capacity to offer more of the same service or product;

- increasing the efficiency of your operations;

- building new overall capability or infrastructures.

This has the advantage that you are quite clear as to what the reason is for the project being undertaken.

Regardless of which way you choose to cut up your project review group, you will find that:

- decisions from two or more groups will come into conflict at some time. It is vital that you have an escalation route to settle these;

- it will sometimes be difficult to categorise a project. This does not really matter, as all projects should be following the same staged framework, which itself leads to more informed decision making regardless of how you label the project.

Finally, when it comes down to making choices between projects, you will need to make sure that the number of projects proposed and undertaken is in line with corporate strategy. You can encourage this by linking the funding of projects to decision making. Two examples of this are provided below.

Example 1

If project review groups are based on market segments you could decide, based on your strategy, which is the most critical and which the least important and ration project funds accordingly. Thus, if the strategy in segment A is to ‘milk cash and withdraw’ you would have no funding for new capabilities or operational improvements unless they can also be applied to other segments. You would allocate the major share of the development funds to the most important emerging segment.

Example 2

If project review groups are based on drivers, you decide, from your strategy, what relative importance you need to put to each driver. For example, if you see a need to increase operation efficiency, you would have more funds for the ‘efficiency’ budget than for the others.

Putting the brakes on

This chapter has dealt with the approach to deciding what to continue, however, business-led projects do not always work out as we expect. In some cases, the development of the outputs proves too difficult, lengthy or expensive. In other cases, the opportunity which was identified has either diminished or disappeared altogether. In both cases, the project may no longer be viable. If you follow the approach in this book, such circumstances would lead to an issue being raised (see Chapter 24) which would be escalated to the project sponsor or higher for resolution. Remember that it is the project sponsor who is accountable for the business outcome, and therefore it is not in his/her interest to continue with an unviable project.

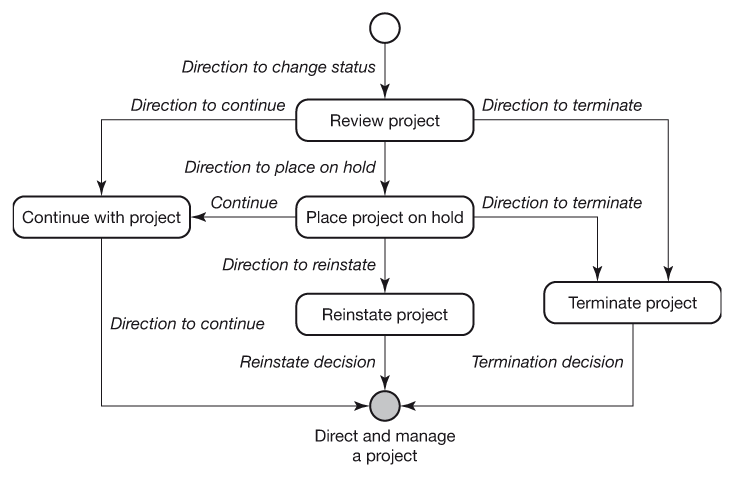

The approach to take is shown in Figure 15.11 and is as follows:

Figure 15.11 Terminating a project

Once the need to terminate a project is recognised, the project should be reviewed to verify this. The review may result in the project continuing, being placed on hold or being terminated. If on hold, the project may later be reinstated or terminated.

Review the project and find out the facts. Exactly what has gone wrong? What possible solution may there be? (Project Workout 24.1 explains a good approach for this). Do not take a knee-jerk decision in the absence of the facts and implications. Undertake the review as quickly as possible; there will be an opportunity later for a deeper investigation, if needed. Following the review you have three possible courses of action:

- continue the project. This may be in an altered form and therefore you may need to apply change control to approve any changes to the business case (see Chapter 25);

- terminate the project, if the project is never likely to be viable (see Chapter 27);

- place the project on hold, pending further investigations.

Placing the project on hold is a ‘half way house’ between continuing and terminating. When a project is on hold, you should not take on any further commitments or start new stages. You should minimise the amount of work undertaken, balancing the need to reduce costs, if it is terminated and maintaining momentum, should it continue. On a practical basis, the ‘on hold’ status ensures you can retain your core project team and facilities in case you restart the project. In addition, there will be cases where health and safety issues require some work to continue (for example, in civil engineering, ensuring tunnels are kept drained). The ‘on hold’ period is useful if the organisation undertaking the project is not able to make a termination decision in isolation, but still needs to protect its interests. Thus a contractor may place a project on hold, pending the client formally terminating it or issuing a change request. Another organisation may need to wait for funding decisions from its banks or other fund providers.

1 See Goldratt, E.M., Critical Chain (North River Press, 1997).

2 Munt, D. and Menard, M., Capital Project Prioritisation and Portfolio Optimisation (Gen Sight, 2002), available at www.gensight.com.