Chapter 6: Manual Control

Introduction

Whereas Chapter 5 dealt with taking partial control of the camera settings, this chapter is about taking complete control of the settings and learning to manually fine-tune them to reflect your artistic, photographic vision. Although we use the semiautomatic settings described in the previous chapter the most, we use manual controls when we are concerned about being able to absolutely reproduce the results.

There are times when you want the exposure and focus to be fixed at a constant value. For example, suppose you want to take a panoramic shot the old-fashioned way, without using the a7/a7R’s Sweep Panorama feature. To do this, mount the camera on a tripod, set the exposure manually, and take a series of overlapping pictures by panning the camera with the tripod head. The focus and aperture must be fixed; they should not change as you pan. After you take all of the pictures, download them to your computer and join them together with third-party software to create your panoramic image.

While more laborious than the automated Sweep Panorama mode, using manual settings provides much higher image resolution. By working with the full area of the a7R sensor, you can, by positioning the sensor for portrait-type framing, collect a series of images that have a vertical height of 7360 pixels rather than the 1856 pixels generated with Sweep Panorama. A knowledgeable photographer can go further and create an even larger panorama by doing multiple sets of sweeps and building one on top of the other. Knowing how to set the camera to manual exposure and manual focus enables you to pursue such strategies for improving your images.

In this chapter we will describe how the manual control extends beyond exposure and focusing. Rather than using incandescent or daylight preset WB settings, you will learn how to set the white balance for any light source. This requires you to set an illuminant’s color temperature value based on the specifications of the bulb’s manufacturer. We will also describe how to calibrate your camera directly to the ambient light if you are dealing with a variety of light sources.

We will also cover the DRO/Auto HDR function. Both DRO and HDR allow you to record an image under difficult lighting conditions. Under bright daylight, it’s difficult to record enough detail in both the highlights and the shadows. When you expose for the highlights, then the shadow areas become impenetrable black masses. When you expose for the shadows, the highlighted areas can be blinding white with little or no detail. When you use DRO/Auto HDR, you obtain an image that shows details in the both the shadows and highlights.

Taking control of your camera enables you to extend your photographic abilities and create artistic, one-of-a-kind shots.

Manual Exposure Mode Controls

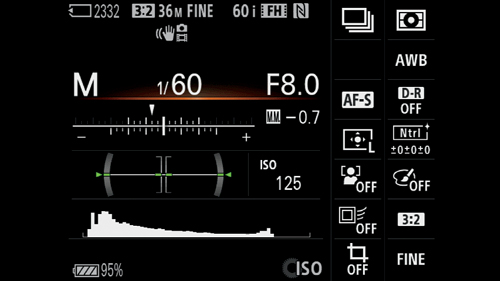

Turn the mode dial to Manual Exposure (M). You will see a display screen (figure 6-1a) with the shutter speed and aperture values displayed at the bottom as white numbers. You can change them by rotating either the rear dial (shutter speed) or the front dial (aperture). In this figure (6-1b), the rear dial is being rotated, changing the shutter speed from 1/160 to 1/60 second. To determine how many EVs you are departing from the recommended exposure, glance at the numbers at the bottom of the LCD screen, to the right of the letters M.M, which stands for “Metered Manual.” In this case, the camera has been set to -0.7 EV. You can see that the shape and position of the histogram has been shifted to the left. There is an exposure bar to the left of -0.7M.M in the [For viewfinder] display (figure 6-1c). The triangle on that bar (to the left of the central tic mark) indicates where the exposure value is set. This exposure bar, which can also be seen in the viewfinder, is a graphical indicator of how far you have departed from the recommended exposure.

Figure 6-1a: Live View in M mode with aperture and shutter speed set to the meter’s recommendation

Figure 6-1b: Exposure set to -0.7 EV from the meter’s recommended exposure

Figure 6-1c: Viewfinder screen showing -0.7 EV offset on the exposure bar

When the camera settings are at ±0.0 M.M., they are set at the recommended exposure. As you deviate from this value, you will see the EV change in increments of one-third of an EV. These numbers help provide an offset value to the recommended exposure. When framing a snow scene, we have determined that applying a +1 EV offset renders the snow as a brilliant white. The camera’s standard ±0.0 M.M. exposure estimate is based on the assumption that the overall scene consists of midtone values, which results in the snow having a dingy gray color.

You can check the effects of offsetting the exposure by studying the LCD screen. The beauty of having a Live View camera is that you can preview the subject before you actually take the picture. In M mode, the brightness of the a7/a7R display screen is an indicator of the appearance of the recorded image. If the sensor receives too little light, you will see a dark screen with muddy colors; if it receives too much light, you will see a bright screen with washed-out colors.

The camera’s exposure can be adjusted by modifying the aperture, shutter speed, and ISO values. The exposure compensation dial is disabled when you set your ISO to a numerical value. In contrast, it becomes active if you use [ISO AUTO]. In this case, when you turn the exposure compensation dial, you change the sensitivity of the sensor.

Extremely Long Exposure “B” Shutter Speed

The longest shutter speed for P, A, and S modes is 30 seconds. M mode gives you more flexibility when shooting in dim light by allowing you to set exposures to at least five minutes. Turn the rear dial to lengthen the value of the shutter speed numbers until you reach “B” (Bulb). This occurs just beyond a 30-second exposure. At this setting, the shutter opens when you depress the shutter button and remains open as long as the button remains depressed. Releasing the shutter button terminates the exposure by closing the shutter. While testing the camera, we successfully captured an image with a shutter speed of five minutes.

If you find that [Bulb] is unavailable, you’ve probably set a command that disables this setting. This includes commands that take multiple exposures, i.e., Multi Frame NR, Auto HDR, Cont. Shooting, and Spd Priority Cont.

For multi-second exposures, the camera should be mounted on a tripod and fired with a remote shutter control. Any camera movement will blur the image, and it is difficult to hold the shutter button down for such a long period without jarring the camera. Also, physically touching the camera may shift its position. If you do this type of work, we recommend getting the Sony cable trigger (RM-VPR1 Remote Commander). When you set the shutter speed to [Bulb], a single press of the remote’s shutter button will open the a7/a7R shutter and keep it open. The RM-VPR1 Remote Commander has a lock so you do not have to continuously press down on the release. You can select this lock and release it when the time is up.

The Appearance of Numbers

Normally the Sony a7/a7R shutter speed is measured in fractions of a second. You will typically see the number presented as a fraction so that “1/4” represents a quarter of a second. However, when you set a shutter speed longer than 1/3 of a second, the display switches from fractions to decimals, so the next longest shutter speed is 0.4. From one second on, the (“) symbol follows the shutter speed number. For example, 1” indicates one second, and 30” indicates 30 seconds.

When the Exposure Set. Guide command is activated, a ribbon is displayed on the screen that shows the f-stop or shutter speed numbers in a larger format. Essentially, this shows what settings are being changed as you rotate the front or rear dial. This strip portrays numbers directly, without the reciprocal sign. The bar will disappear after a short time of inactivity.

MENU>Custom Settings (2)>Exposure Set Guide>[On], [Off]

One drawback is that the exposure setting guide obscures the histogram while adjusting the aperture or the shutter speed. For this reason, we prefer to keep this guide turned off.

Noise Reduction with Long Exposure

Images taken with long exposures may suffer from a special kind of noise. This noise appears as bright (hot) pixels that stand out against the black background. The Long Exposure NR command reduces this effect by using a procedure known as dark frame subtraction whenever the shutter speed exceeds one second. The Long Exposure NR command is set as follows:

MENU>Camera Settings (5)>Long Exposure NR>[On], [Off]

This process requires taking two images to create a single image and will operate only in shooting and drive modes where only a single image is being recorded. It will not work if the camera is recording a continuous series of images, such as when in Sweep Panorama or SCN’s Hand-held Twilight or Anti Motion Blur modes. Also, this command is not available in any of the Continuous and Bracket Drive Mode options. It does, however, work on both RAW and JPEG files.

When the Long Exposure NR command is turned [On] and the exposure is one second or longer, the following steps occur:

- When the shutter button is pressed, the camera records the image, including the noise generated by the sensor.

- The camera takes a second exposure but does not record an image. This is the so-called dark frame, which creates a reference map for the previous image’s noise pattern.

- The camera subtracts the hot pixels recorded in the dark frame image from the first image to reduce the appearance of noise in the final image. The Long Exposure NR command doubles the time it takes to record an image.

The Long Exposure NR command doubles the time it takes to record an image. For example, you take a photograph with a 10-second exposure, the camera will automatically take a subsequent exposure of 10 seconds to create the dark frame. Then the camera processes the subtraction to remove the noise from the first image. For exposures that run more than several seconds, this can create a tedious wait, so some people turn this command off.

Most of our exposures are less than one second in duration, so having this command turned on makes no difference. For the few pictures we have taken with exposures of several seconds or more, we have been pleased with this command’s results. It is only when exposures are 30 seconds or longer that we think about turning the command off. Again, when using long exposure times, make sure you mount the camera on a tripod, trigger the shutter with a remote control, and turn off the SteadyShot option.

Noise Reduction at High ISO

As we mentioned previously, using a higher ISO results in increased noise, so we tend to photograph at an ISO of 1600 or lower. If you are forced to work at a higher ISO, you might want to try this in-camera noise reduction option. It only works on JPEG files, and is used with ISO 1600 and higher. The High ISO NR command does not require a second exposure to capture a dark frame; instead, it works on just one image. You can set noise reduction to [Normal], [Low], or [Off] with the following menu command:

MENU>Camera Settings (5)>High ISO NR>[Normal], [Low], [Off]

This command essentially blurs the image and smoothens the appearance of noise, at the expense of image sharpness. It can be used when you fire continuously. Be aware that the command can take some time to execute, so the noise reduction feature may slow down the frame rate when you use continuous firing. We set High ISO NR to [Low] when shooting JPEG files. When we shoot RAW and JPEG files together, we set the command [Off]. We do not use the default setting of [Normal] because it destroys fine detail. Instead, when we shoot RAW and JPEG files together, we set it to [Off]. The command only acts on the JPEG files; not on RAW files. When shooting in low-light conditions, we prefer saving the picture as a RAW file and removing the noise later with third-party noise-reduction software. We use Noise Ninja, which seems to reduce noise with less detail loss than the Sony a7/a7R High ISO NR option.

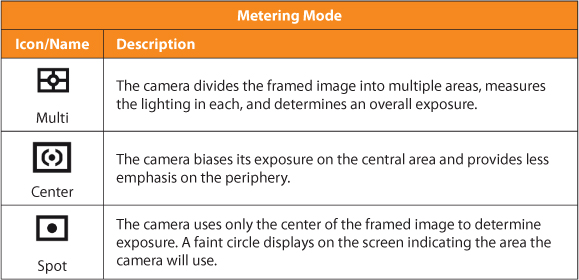

Metering Modes

Controlling your exposure is critical, so it is important when using the manual settings to know where and how your camera’s light meter measures intensity. The Sony a7/a7R’s built-in light meter uses three metering modes (table 6-1). You can access the options with the following command:

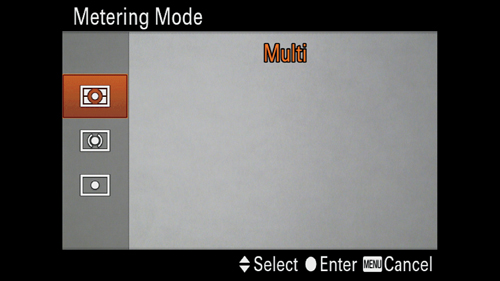

MENU>Camera Settings (4)>Metering Mode>[Multi], [Center], [Spot]

The above command can be set quickly using the Quick Navi screen or the Fn button (figure 6-2).

Table 6-1: Metering Mode command options

The default and most commonly used method is [Multi], where light over the entire area of the framed image is used to calculate the exposure. This is more than a simple average—it is a complex computation that ensures a balanced exposure for a wide variety of subjects. Camera manufacturers originally developed these calculations for film cameras, and later refined them for digital cameras.

Figure 6-2: Metering Mode’s three options, with [Multi] selected

Although early versions of this option were unreliable, they have improved over time, and have enabled [Multi] to serve as a workable exposure method for the Sony a7/a7R’s automatic exposure modes. For manual exposure, it serves as a good starting place since you can override the recommended exposure easily. As you take over the camera’s operation, it will, at the very least, do a good job of putting your exposure in the ballpark. The results are quite good, and you can refine them by studying the live histogram and adjusting the exposure slightly. Again, the advantage of having a Live View camera is the ability to ascertain if you need to modify the exposure before you take the photograph.

The second metering method is [Center], which uses an easily understood algorithm for evaluating exposure. It is based on the assumption that the most important part of the picture is in the center; therefore, the meter biases the exposure toward that region of the display to assure that the subject in the center is well exposed. The peripheral areas are also measured, and contribute to the overall exposure, but they are given less priority. Historically, this was a popular way to measure light in an SLR camera. Although this older technology has the virtue of simplicity, it is not as reliable as [Multi] area metering. We rarely use this type of metering since, in comparison to [Multi], it results in a higher percentage of unacceptable exposures.

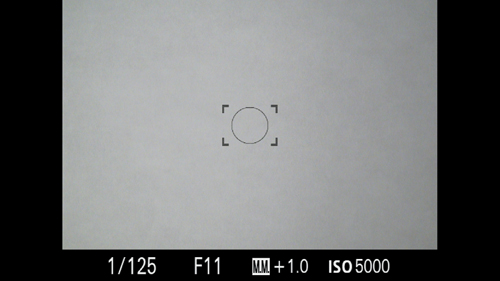

The third and most direct way to meter is [Spot]. This is for the careful photographer who is knowledgeable about the camera and the desired results. It requires great care to use properly because it converts your camera into a light meter; you will have to mentally calculate how to use exposure data to create your picture.

When selected, you see a small circle in the center of the screen that marks the area being measured for light (figure 6-3). This is a target site, and it is sighted to measure the intensity of the light within its circumference. It requires finesse and thought to interpret the reading. For example, we will use spot metering when photographing people on stage, for instance a piano recital, where the performer is lit with a spotlight and the remainder of the stage is black. Under these conditions, you determine the exposure for the shot by using [Spot] to measure the light reflected off of the performer’s face. We find that giving the facial tones about +0.7 EV (for a fair complexion) records bright, clean skin tones. For people with darker complexions, we provide less exposure, maybe -0.7 EV, so as not to wash out the subject’s rich complexion. As you can see, using the [Spot] meter is not a point-and-shoot operation. It requires experience. However, when using this metering option, you obtain the most accurate data for determining exposure. In the above recital example, the black background behind the spotlight does not influence the exposure reading. We have found that spot metering and photographing in M mode yields superior results to using the camera in [Multi].

For technical work, we take advantage of spot metering when photographing manuscripts. We find that putting the spot meter on the white page and overexposing by 1 2/3 f-stops records an excellent image with black text against a white background. If we do not apply exposure compensation, the white paper will appear dingy and will be a darker shade than it should.

Figure 6-3: Display screen showing the spot meter’s target circle for measuring light

Manual Focusing: Overriding Automatic Focusing

In Chapter 5 we described how to use the menu to reset focus using the Focus Mode command. We discussed using the two options, [Single-shot AF] and [Continuous AF], for semiautomatic shooting modes. In this chapter, we will discuss the remaining two options, [MF] and [DMF], so you can manually focus the camera.

MENU>Camera Settings (2)>Focus Mode>[MF] or [DMF]

While the command can be selected within the camera’s menu, you may find this to be too inconvenient for fast operation in the field. We have found it more convenient and faster to use either the Fn button and select the Focus Mode or to use the Quick Navi screen.

[DMF] stands for Direct Manual Focus and is supposed to provide a quick means of touching up automatic focusing. When this option is selected, pressing the shutter button halfway initiates the autofocus. When focus is established maintaining pressure on the shutter button allows you to adjust focus with the lens-focusing ring. The picture is taken by fully pressing the shutter button down. Our main complaint about using [DMF] is its quirky behavior and occasional unreliability. It first requires the camera to acquire focus automatically. Once it does so, you must maintain a light pressure on the shutter button to activate the lens-focusing ring. If you relax pressure prematurely, the ring’s function is disabled. Then, because you failed, the process has to be repeated. Aside from wasting time, this option can be extremely aggravating. Failure to find focus will make manual focus unavailable and you will have to change your Focus Mode. We much prefer using the [MF] option, which allows us the surety of having the focus ring active at all times.

When you try your hand at focusing manually, you will discover that Sony has provided options for making this task easier. If the goal is to switch strictly to manual focus, you will find the AF/MF button can be even faster and more convenient, given that you have some additional command settings. In order to experiment with these features, put your camera in MF mode. Be aware that the camera’s factory default requires you to press the AF/MF button in to maintain manual focusing. Once you release the button, the camera reverts to automatic focus. To use this button in a way that one press puts the camera in MF mode and then another press puts it back into AF, set the AF/MF button with the following value:

MENU>Custom Settings (6)>Custom Key Settings>AF/MF Button>[AF/MF Ctrl Toggle]

We find the above option convenient because you don’t have to maintain continuous pressure on the AF/MF button for manual focusing. If your viewfinder and LCD display are set to [Display All Info.], there is an icon on the left side of the screen that lets you know if the button had been set for MF or AF.

MF Assist

You may find that your view of the subject does not provide enough magnification to see fine enough details for accurate focusing. The most direct piece of assistance is [MF Assist], which magnifies the center of the screen so you can see those fine details. This ensures your focus is precisely spot-on. When using the camera in the field, we found the display screen’s base magnification to be insufficient to find precise focus (figure 6-4a). If you have to focus by judging the sharpness of the image, we recommend using the viewfinder—its higher resolution shows finer details.

We use MF Assist extensively, especially when we photograph with a long telephoto lens, where increasing the magnification of the display screen makes finding focus much easier. This is accomplished by activating the MF Assist command:

MENU>Custom Settings (1)>MF Assist>[On], [Off]

When this command is set to [On], the camera provides two levels of magnification: 5.9X and 11.7X for the a7, and 7.2X and 14.4X for a7R. When in Manual Focus mode, turn the Sony lens’s ring to focus and the camera magnifies the image by the lower magnification. Typically we find this magnification sufficient (figure 6-4b), but if you find this is not the case, you can jump from the lowest power to the highest power by pressing the center button (figure 6-4c).

Figure 6-4a: Screen at 1X magnification, MF Assist [Off]

A second tool to help you determine if your subject is adequately focused is to use the following command:

MENU>Custom Settings (1)>Focus Magnif. Time>[No Limit], [5 Sec], [2 Sec]

Figure 6-4b: Screen at 7.2 magnification, MF Assist [On]

Basically, this command determines how long the magnified view is maintained. Once you stop turning the lens-focusing ring, you can retain the enlarged image indefinitely or for either two or five seconds before the magnification drops down to 1X. Remember that in this command, the magnified view shows only a partial field of view, and you will need to drop down to 1X to frame the scene properly.

Figure 6-4c: Screen at 14.4X magnification, MF Assist [On]

When using the Sony AF lenses, you will find that when [MF] is selected with MF Assist, turning the focusing ring automatically raises the magnification of the screen to 7.7X. Remember that the timer starts only after you stop turning the lens-focusing ring, which can be accomplished in less than a second. Under these conditions, we find that two seconds (the default value) is long enough to find focus. If you need to drop down to the screen’s base magnification, you can do so immediately by applying slight pressure on the shutter button.

When using the camera with macro focusing lenses, microscopes, telescopes, extreme telephoto, or legacy lenses, we set the option to [No Limit] because these conditions takes more time to operate. We find that the automatic reduction of magnification disrupts our workflow. The long duration is not a handicap since you can return to base magnification by lightly pressing the shutter button.

MF Assist function has one limitation. When you use it, you only get a partial field of view so you may end up viewing an unimportant part of the image. This can be confusing when it occurs unexpectedly. To get a preview of where the MF Assist will be more beneficial, execute the Focus Mode command. Unless you have already changed the button’s assigned command, the C1 button’s factory default is Focus Settings. If you have set your camera to manual focus, C1 turns on the MF Assist. In this operation, pressing the C1 button shows an orange rectangle of where you will magnify your scene. A second press of that button results in the magnification setting of 5.9X for the a7 and 7.2X for the a7R. A third press gives you 11.7X for the a7 and 14.4X for the a7R. A fourth press drops you down to 1X.

When you initiate your first C1 press, you’ll see an orange rectangle, which you can aim at your target. A second press of C1 enlarges the image, and if you need to you can move the magnified region with the directional (right, left, up, and down) buttons. Press the C3 button to return to the center of the screen. You can also use the rear dial and move the rectangle horizontally. The front dial and control wheel move the rectangle vertically. When using the viewfinder, we prefer using the rim of the control wheel for positioning the rectangle. It may be just us, but we found using the dials and wheels to be awkward and inconvenient.

Peaking and Focusing

Peaking is a colorization strategy that highlights the borders of in-focus areas. You can determine the size and color of the fringes (figures 6-5a and 6-5b). They appear only when you use manual focus and are not recorded with your picture or movie.

There are two commands involved with the peaking function. The first allows you to set the level of peaking. The second command allows you to set the color of the highlights.

MENU>Custom Settings (2)>Peaking Level>[High], [Mid], [Low], [Off]

MENU>Custom Settings (2)>Peaking Color>[Red], [Yellow], [White]

Peaking has two advantages. First, you see the full image; it does not limit the field of view through the finder. You will see all of what the sensor is seeing, which will help with overall composition. Second, it is active while you are taking movies. By comparison, MF Assist can only be used just prior to the start of recording a movie. Once you are actually recording, it becomes unavailable. Since the Peaking color fringes are not recorded, your movie will appear in its natural format.

Figure 6-5a: Peaking activated at [Low] setting

Figure 6-5b: Peaking activated at [High] setting

With these advantages, you would think everyone would embrace this technology; however, Peaking does have flaws. First, and most important to the still photographer, is the distracting nature of the fringes. When its level is set to [High], its appearance at the borders interferes with careful composition. Second, there is a question of whether Peaking is as precise as MF Assist when you need critical focusing. Our feeling is that for precision macro or scientific work, Peaking is less accurate. While we find Peaking eminently useful for movie taking, we prefer using MF Assist for our still photography. The good news is if you like this function and want to use it off and on, it is an available option for several of the customizable keys.

The setting of the Peaking Color and Level depends on the scene and its overall color scheme and contrast. We are split on our preferences—one of us prefers yellow for their work and the other prefers red. The Peaking Level option depends on the intrinsic contrast of the scene. With high contrast, it is better to use [Low] because the fringes can be large and distracting when focus is reached. In a low contrast scene, [Low] produces such small fringes that they do not aid in focusing. Under these conditions it is better to use [High] to make them visible.

Aperture and Zoom Lenses With Manual Focusing

To achieve the most accurate focus, you should have your lens set at is widest (maximum) aperture. This is attained easily in P and S modes and is Sony’s normal operating strategy when using autofocus lenses. These lenses are always set to the maximum aperture while viewing a subject in Live View. When the aperture is changed via the control dials in these modes, the physical lens aperture actually stays fully open while the camera is calculating what the exposure should be with the new setting. When you press the shutter button, the lens aperture will close down to the chosen setting as the camera takes the picture.

This is not the case if you use A or M mode. As you preview the scene and decide to use a narrower aperture, the lens diaphragm closes down immediately and is set to the working aperture at which the picture will be taken. This provides the benefit of seeing the increased depth of field in real time. However, this is not ideal for accurate focusing because the increased depth of field makes it difficult to judge the precise point of focus. You can see this for yourself if you attempt to focus in A mode and compare the ease of focusing between a lens used at f/4 to one set to f/22. In the former case, as you turn the focusing ring, the image appearance changes with alacrity from tack sharp to blurry. If you set the aperture to f/22, the transition from sharp to blurriness occurs gradually, making it difficult to judge where the precise focus point is. If you use P or S mode, the focus always appears to change quickly, regardless of the lens’s aperture setting.

The important message in this section is that accurate manual focus is obtained most easily when the lens is at its minimum depth of field. This rule can be extended to zoom lenses. A zoom lens will show a narrower depth of field when it is set to its maximum focal length. To accurately focus this lens, you would do so at this focal length. If you zoom back to get a wider field of view, focus will be maintained. In contrast, if you attempt to focus at the minimum focal length of this lens, you will find that as you zoom in, the focus point will change. In summary, to get the most accuracy in manual focusing, use the longest focal length of your zoom lens.

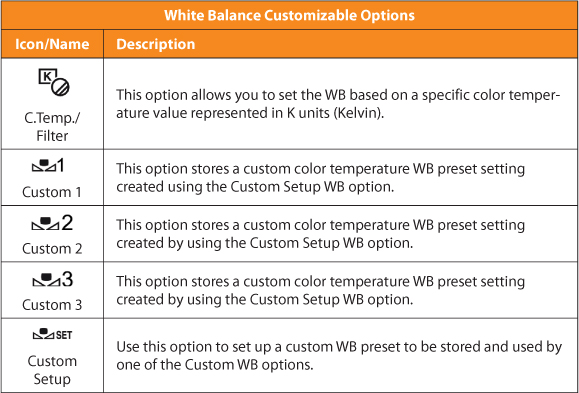

Manual Adjustments of Color Temperature

In Chapter 5 we described how to use preset WB values by matching a light source to an icon. However, there are two other ways to set WB: by selecting a specific color temperature and by saving a customized white balance. Table 6-2 contains icons pertaining to these two methods. Both will require some effort.

Table 6-2: A listing of color temperature icons

First, you can get to the WB screen through the menu:

MENU>Camera Settings (4)>White Balance>[C.Temp./Filter], [Custom 1], [Custom 2], [Custom 3], [Custom Setup]

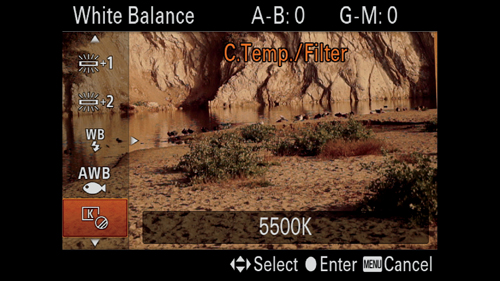

Rather than setting the WB through the menu, we take advantage of the control wheel’s right button (with the WB label) to provide quick access to White Balance (figure 6-6a).

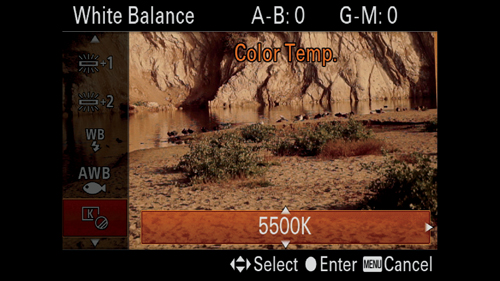

Once you press this button, you will see various option icons on the right side of the screen, along with the description of the highlighted option at the top. Scroll through the options until you reach [C.Temp./Filter] (figure 6-6a). If you press the right button, you will enter the Color Temp. screen, which has an orange bar containing a 4-digit number preceding the letter “K” (the abbreviation for Kelvin). The up and down arrows indicate how to move through the available temperatures (figure 6-6b). The 4-digit number ranges from 2500K to 9900K. Use the up or down button, or rotate the control wheel or front and rear dial, to navigate through the range. The numbers change in increments of 100.

These numbers represent temperatures or light-source colors, and allow you to set your camera’s white balance to a specific color temperature. Artificial light sources, especially tungsten lamps, are rated by their manufacturer in degrees Kelvin. You can calibrate your camera’s sensor to the lamp’s specifications. Rather than discuss the scientific and physical basis for this scale, it is sufficient to say that when you dial in the appropriate numeric value for a light source, your camera should be calibrated to that light.

Figure 6-6a: WB command’s C. Temp./Filter option

Figure 6-6b: Setting the color temperature to 5500K

To perform this operation, you need to know the color temperature of the light source— information the manufacturer supplies with their bulbs. For example, the tungsten bulb on our microscope is rated at 3200 K, a value provided by the manufacturer, Osram. So, we can set [C.Temp./Filter] to this number when taking pictures through our microscope. Most technicians realize this value is approximate. The bulbs age with time, and as the glass envelope becomes coated with tungsten from the filament, the light is filtered and becomes cooler in color temperature. Also, with an incandescent light source, the color temperature depends on the operating voltage. Bulbs emit a warmer color with a decline in voltage. For the most critical work, a color temperature meter is used to measure the light’s output to ensure consistent color recording. These are expensive instruments and can cost more than your camera and lens combined. Fortunately, your Sony a7/a7R has this capability built into its software.

Custom White Balance

Only rarely do we use the color temperature scale. Instead, we use the Custom WB feature, which works effectively with any light source. It sets the camera’s white balance by calibrating it directly to the light. This value is saved and can be used as if it is a preset WB value. To do this, all you need is a blank sheet of white paper. The following steps outline the process:

Figure 6-7a: WB set for Custom Setup WB

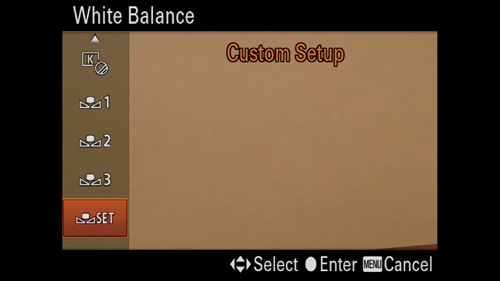

- Press the WB button and scroll through the options with the control wheel. Highlight the option [Custom Setup] (figure 6-7a).

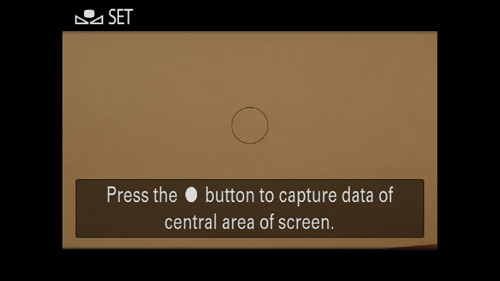

- Press the center button. A new screen appears with a finely inscribed circle in its center and the message: “Press center button to capture data of central area of screen.” Figure 6-7b shows a white sheet of paper occupying the whole field of view. Note the color of the paper. In this case the white balance is not set correctly, causing the white paper to have an orange cast.

Figure 6-7b: Gray circle indicating where to place a piece of white paper in the frame

- Place the white paper so the circle is filled, and then press the center button (figure 6-7c). The white paper serves as a reflector and provides a screen for displaying the illuminant’s color.

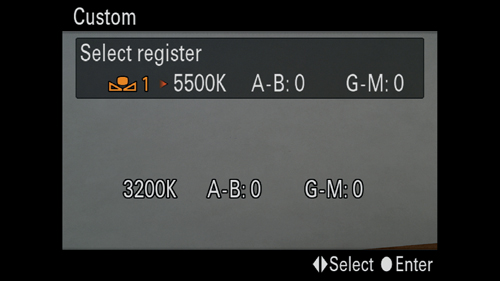

- You will hear the camera take a picture. A new screen appears with a gray rectangle stating: “Select register” along with the color temperature in K and two numbers, one following A-B and one following G-M (figure 6-7c). The gray color reflects that the white balance has been set correctly.

- Use the left and right buttons to select a register number, 1, 2, or 3, to store the color temperature value and press the center button.

You can store up to three custom values, one value in each register. These become preset WB values that are available to you when you press the WB button and select the appropriate register number. These numbers are retained even if the camera is turned off.

Custom WB is easy to use. In fact, we use it routinely for our technical photography. For example, when working with a microscope, we remove the specimen from the field of view and calibrate the WB setting against an unobstructed region. The camera is directly calibrated to the light. This is more accurate than using a color temperature scale because it compensates for color cast imparted by the optics of the microscope. We described earlier how the color temperature of an incandescent bulb changes with age. Using Custom WB just before a photo session compensates for this.

Fine-Tuning WB: Fine Adjustment of Amber-Blue and Green-Magenta

On every WB preset selection, you can fine-tune the color further by providing hues to the image. These change the ratio of amber to blue (A-B) and the ratio of green to magenta (G-M). This can counteract an undesirable tone resulting from unusual lighting conditions. Your subject may be under several different types of lights. For example, an interior scene might be lit by daylight streaming through the window, an incandescent light sitting on the table, and fluorescent lights hanging from the ceiling. These extreme conditions can cause an undesirable color cast in the image. Fortunately, this can be corrected by adding a slight tint to the image. The slight hue addition will be recorded in both JPEG and RAW files.

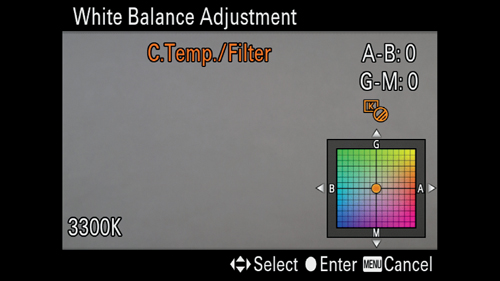

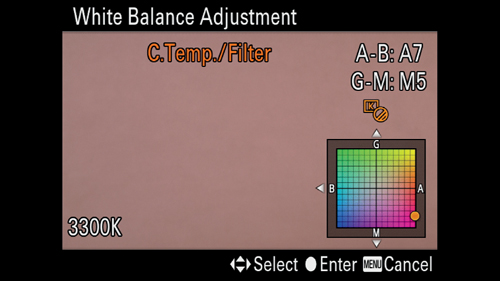

When you select a WB preset, press the right button and a screen with a large square consisting of smaller, multicolored squares will be displayed. The only exception to this is the Color Temperature/Filter option. In this case, press the right button twice. The first press calls up the color temperature values, and the second press calls up the multicolored square.

Figure 6-8a: WB color fine adjustment screen

Figure 6-8b: WB fine adjustment being applied

At the center of this multicolored square is an orange circle (figure 6-8a). Press the control wheel’s rim to move the circle within the color square. Move the orange circle horizontally to apply either blue or amber. Move the orange circle vertically to apply green or magenta (figure 6-8b). You can see the effects of these color changes in your Live View screen.

As noted earlier, these hue adjustments are needed for correcting color tints when several different light sources are used. This need can also arise if you use a single light source that emits a discontinuous spectrum, such as fluorescent or LED light. When this type of lighting illuminates your subject, you may find that your images has a color cast that cannot be removed by simply selecting a preset WB value. You can use this fine adjustment process within the camera to deal with undesired coloration.

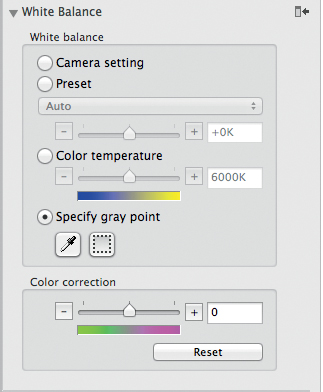

Earlier, we recommended that you save your images as both RAW and JPEG files. Each file format has its advantages. A major benefit of saving in RAW format is the ease of correcting WB errors outside the camera. We use either Sony’s Image Data Converter software or third-party software, such as Photoshop or Aperture, for touching up RAW images. Figure 6-9 shows the Image Data Converter software’s slider and a color temperature scale. The slider allows you to rapidly evaluate different color temperature settings. Additionally, the selection marked “Preset” displays a variety of light sources, enabling you to find your illumination type.

Figure 6-9: Image Data Converter controls for adjusting a RAW file’s color temperature

If you record an image of an 18% gray card, you have a quick means to calibrate the Image Data Converter software to the card’s color temperature. Use the card as a target for the software’s Specify gray point command. Since the card serves as a neutral reference, the software attempts to render it as gray without tinting. Notice the icons under Specify gray point; you can select either an eyedropper or a selection box and target part of the 18% gray card. The eyedropper is basically a pointer. When you select it, you can guide it to the precise point in the gray image that you wish to use to set your white balance. Keep in mind that it should be used with images that have little chroma noise. If your picture is taken in poor light and you see colored speckles in the gray card, you will get more consistent adjustments by using a rectangle for selecting the card. Using the larger area averages the chroma noise and provides a truer measurement of the gray card’s surface.

Lens Compensation

To obtain the ultimate picture quality, the a7/a7R has software that corrects imperfections introduced by the lens. These imperfections include vignetting (peripheral shading), distortion (geometric distortion), and chromatic aberration (color fringing). Vignetting is a common lens defect in wide-angle lenses. It generates an image where the periphery is darker than its center. Distortion indicates that parallel straight lines bow in (pincushion distortion) or bow out (barrel distortion). Finally, chromatic aberration is when the subject’s borders have red or blue fringes due to the inability of the lens to bring all wavelengths of light to the same focus.

Correcting these problems with software requires an in-camera database to catalog the lens defects and a processing algorithm to correct the image. Sony periodically provides updates to the camera’s firmware, expanding the database as new lenses are introduced into its lineup. Remember, this correction is a software alteration of the image that provides a modified image file. For scientists requiring unaltered images, these corrections should be turned off even if the recorded image shows all of the lens defects.

The chromatic aberration and shading correction default setting is [Auto], so if the attached lens is in the database, its optical faults will be corrected in JPEG files. RAW files are not corrected and will show the image defects. Curiously, at the time of writing, when the 28-70mm Sony FE and the Carl Zeiss 24-70mm zoom lens are mounted, the Distortion Comp is grayed out and unavailable for adjustment. Normally, when available, you would select it and make sure it is set to [Auto].

Here are the three lens compensation commands and their individual options:

MENU>Custom Settings (5)>Lens Comp.>Shading Comp.>[Auto], [Off]

MENU>Custom Settings (5)>Lens Comp.>Chro.Aber. Comp.>[Auto], [Off]

MENU>Custom Settings (5)>Lens Comp.>Distortion Comp.>[Auto], [Off]

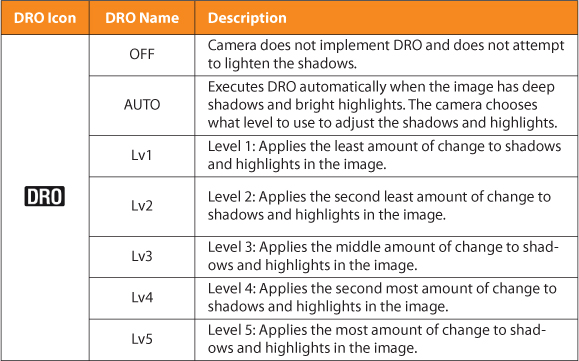

DRO/Auto HDR Function

When photographing, you sometimes encounter a scene with overly bright regions that show little to no detail. Or you might encounter a subject with deep shadows that appear as a featureless black mass. Many of these problems can be corrected or ameliorated by downloading the image to a computer and post-processing it with programs like Photoshop or iPhoto. But Sony has designed the a7/a7R so you can reduce these deficiencies in the camera with two processes: Dynamic Range Optimization (DRO) (figures 6-10a and 6-10b) and Auto High Dynamic Range (Auto HDR) (figure 6-11a). When you select either of these operations, the camera will process the image automatically and save it to your memory card. Figure 6-11b is the result of taking three shots of varying exposures and combining them into one image using Photomatix software. You can see the extent of how Auto DRO, Auto HDR, and Photomatix bring out the shadow details.

Figure 6-10a: Image without DRO Auto

Figure 6-10b: Image with DRO Auto

Figure 6-11a: Image made with Auto HDR

Figure 6-11b: Image from Photomatix

Choose DRO when one exposure can record all of the intensity values for the scene. If the scene has too great a variation in intensity values and the extreme light levels overwhelm the sensor, use Auto HDR. This setting employs three exposures taken in rapid succession: one for recording highlights, one for recording midtones, and one for recording shadows. By using multiple exposures, you can record a greater range of intensities than can be recorded in a single photograph. By combining these three images, it is possible to create a composite where shadows can be lightened, highlights can be darkened, and midtones can be maintained.

The DRO and Auto HDR functions are accessed through the menu, where you can turn both functions off or select one of them:

MENU>Camera Settings (4)>DRO/Auto HDR>[D-R Off], [DRO], [HDR]

DRO Function

Access the DRO function with the following command. Note that DRO has a list of suboptions to choose from.

MENU>Camera Settings (4)>DRO/Auto HDR>DRO>[AUTO], [Lv1], [Lv2], [Lv3], [Lv4], [Lv5]

The DRO function submenu options are shown in table 6-3. The DRO level options determine the extent to which shadows are lightened in an image—the maximum effect occurs at [Lv5], and the minimum effect occurs at [Lv1]. To select a specific Lv value, highlight the DRO activated [AUTO] option and press the right or left button to navigate through the options. Use the center button to apply the selected value to the DRO function.

Table 6-3: DRO options of the DRO/Auto HDR command

It is difficult to estimate what level you need for a given scene. We recommend trying each of the levels until you get to know how the results look. With practice, you should be able to implement this function to your liking. Although the camera makes the level decision for you when set to [AUTO], this does not guarantee that you will like the image that is recorded.

When you select a specific level, the DRO icon will appear on the display screen along with the level you selected for both [Display All Info.] and [For viewfinder] data display formats.

The DRO command is available in P, A, S, M and Movie modes only. For still pictures, you can shoot in RAW or JPEG or both. RAW files, when opened with most image-processing software programs, do not show the effects of DRO. So when you photograph in [RAW&JPEG], you will find that the RAW files look unchanged, while the JPEG files show the effects of DRO. One program where you can see a RAW file emulating the contrast changes with DRO is Sony’s Image Data Converter 4.0.

You can use DRO with a Creative Style to affect your picture’s results, but not a Picture Effect. When you have DRO active and select a Picture Effect option, the DRO value will change to [D-R Off]. It will be changed back to its previous value when you set the Picture Effect command to [Off].

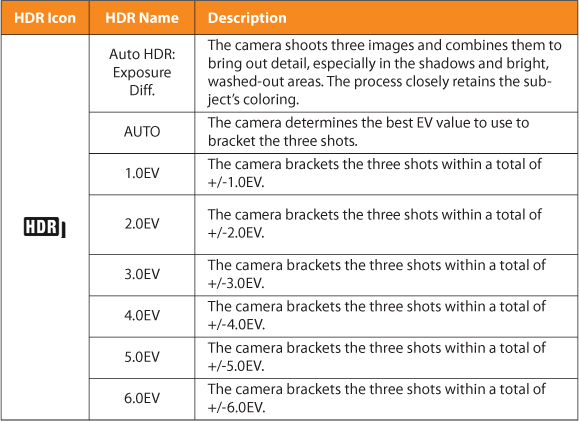

HDR Function

Traditionally, HDR photography involves downloading pictures taken with different exposures and combining them together on a computer to form a composite image with all the intensity levels from the scene digitized. Then tone mapping, a program for manipulating contrast, brightness, and color, is used to create an image that displays details in the brightest and darkest areas of the scene. With scenes that have a wide range of intensities, HDR photography frequently produces an image with oversaturated colors, which gives it a surreal appearance. For example, when you merge three different exposures with third-party software like Photomatix, the final composite image can have dramatically different colors than the original scene (figure 6-12). You can be aggressive with this approach and bring up the dark tones and bring down the bright tones to create an image, which shows more detail than that achieved in figure 6-11a.

Figure 6-12: Image created by merging three exposures in Photomatix

When you use the Auto HDR function, you might be surprised to find that the final image does not have the supersaturated colors that it did when the same images were processed with Photomatix. Instead, the color balance and saturation of Auto HDR are similar to a DRO image. It appears that Sony engineers have adjusted the Auto HDR output so that the resulting image retains the color balance and tonality associated with a typical photograph. To mimic the surreal appearance characteristic of HDR images, you might want to try the Picture Effect [HDR Painting] option. Unfortunately, this effect does not work with the Auto DRO/HDR command because it can only be applied to photographs taken with a single shot. Unlike when you create this effect with third-party HDR software (which uses three exposures—one underexposed, one normally exposed, and one overexposed), images taken using the [HDR Painting] effect are limited to the dynamic range of the single exposure. Its surrealistic appearance cannot match what can be obtained by post-processing with software such as Photomatix.

Even though Auto HDR and DRO address the same problem of intensity extremes in a picture, there are important operational differences. First, DRO images can be captured in RAW format and Auto HDR function cannot. Second, DRO works on the information obtained from one image while Auto HDR works on three. DRO images will therefore have higher noise levels in the deep shadows than the images generated from Auto HDR. Remember: one of the three exposures in Auto HDR is used for capturing shadow detail and will reduce noise in this area of the image. In contrast, DRO uses image processing to increase the brightness in the shadow areas, which amplifies the appearance of sensor noise. Third, DRO has the advantage of working on a scene where the subject is moving, and for taking movies. The three exposures used in Auto HDR preclude its use for moving subjects or movies. Curiously, of the three pictures Auto HDR takes, only two are saved on the memory card: one with the normal settings and one of the merged image.

The following command enables the Auto HDR process, and the options are described in table 6-4. Again, like DRO, the HDR command has a list of suboptions to select from.

MENU>Camera Settings (4)>DRO/Auto HDR>HDR>[AUTO], [1.0EV], [2.0EV], [3.0EV], [4.0EV], [5.0EV], [6.0EV]

After the Auto HDR command is selected, you have the choice of letting the camera determine the best EV by setting [AUTO]. Alternatively, you can take control and select a specific EV value ranging from 1.0 to 6.0. The selected value becomes the ± range over which the three shots are distributed. Use a low EV value when the scene has a moderate range of light intensities; use a high EV value when the range of intensities is more extreme. To select a specific EV value, press the right button to enter the submenu. Use the right and left buttons to navigate through the options. Press the center button to apply the selected option to the HDR function.

Table 6-4: HDR options of the DRO/Auto HDR command

The Auto HDR function is available in P, A, S, and M modes only, and it can only save JPEG files (Quality = [Extra Fine], [Fine] or [Standard]). If the camera is set to HDR on, and then you to set the Quality value to include RAW, the DRO/Auto HDR command’s value will be changed automatically to DRO’s on option but does not automatically change back if you reset the Quality command to a JPEG-only value.

As with DRO, you can use Auto HDR with a Creative Style to affect your results but not a Picture Effect. When you have Auto HDR active and select a Picture Effect option, the Auto HDR value will change to [D-R Off]. It will be changed back to its previous value when you set the Picture Effect command to [Off].

When you select a specific EV, the HDR icon will appear on the display screen along with the level you selected for both [Display All Info.] and [For viewfinder] data display formats.

Using DRO and Auto HDR

We encourage you to try these imaging techniques and see if they help your photography. They can be a benefit. As you gain more experience, you may decide to forego using these processes within the camera and start using them as post-processing procedures.

If you wish to mimic the effect of using a DRO Lv level, you can use Sony’s Image Data Converter for working on your RAW files. We prefer it to the camera’s internal processor. Even though Image Data Converter’s effects are not identical, it is similar enough to improve the image. Its greatest advantage is that you can try several levels of DRO on one image, and also specify adjustments to the highlights and shadows. Our problem with using DRO in the camera is that it requires considerable expertise to pre-visualize its effects before taking the picture. We find it simpler to take RAW images with DRO off and then improve the images on our computer using either Image Data Converter or the “Curves” tool in Photoshop.

We have found DRO to be a powerful benefit when recording movies. The ability to post-process these files may be limited, and DRO provides a simple means of taming contrast extremes to make a pleasing movie.

Like DRO, Auto HDR can improve an image, but also like DRO, it is difficult to anticipate the recorded image’s appearance. We prefer shooting in RAW, which is not available with Auto HDR. We can take multiple images, bracketing the exposure, and then post-process the RAW images on our computer with Photomatix, which allows us to experiment with different interpretations of the composite image.

Bracketing and Dynamic Range

The a7/a7R has a special feature for dealing with unusual lighting conditions. It can be set to capture three images, each recorded with a slightly different setting. The process is done as bracketing and it can be considered a shotgun attempt to find the ideal setting. These features are available as Drive Mode command options that control variations in the light level, WB, or contrast.

To vary the light level on the sensor, press the Drive Mode button. Scroll through its options with the control wheel until you highlight a rectangle containing the letters BRK. Outside the rectangle is the letter C. This is the icon for [Cont. Bracket]. Press the right button to scroll through the following options: [0.3EV 3 Image], [0.3EV 5 Image], [0.5EV 3 Image] [0.5EV 5 Image], [0.7EV 3 Image], [0.7EV 5 Image], [1.0EV 3 Image], [2.0EV 3 Image], and [1.0EV 3 Image]. You will see your selection displayed along the top of the screen.

The EV values refer to the +/- variation in exposure that will be applied, and the number preceding “Image” indicates the number of pictures that will be taken. So in the case of [1.0EV 3 Image], three pictures will be taken, one at 1.0 EV beneath the camera-recommended exposure, one at the recommended exposure, and at 1.0 EV over the recommended exposure.

When you find the exposure variation that suits your needs, press the center button. To take the picture, press the shutter button and keep it depressed until all the shots are fired. If you raise your shutter finger too soon, you will not complete the series.

You can specify the order of pictures that will be saved to your card with the menu commands listed below. The default option is to first save the camera-recommended exposure, then save the shortest exposure, then save the longest exposure. This is also the order in which the camera takes the pictures: a normal exposure, an underexposed image, then an overexposed image. However, you can use a different sequence where it starts from the lowest exposure and then sequentially takes the higher exposures. To do so, use the following command:

MENU>Custom Settings (4)>Bracket order>[0![]() —

—![]() +], [—

+], [—![]() 0

0![]() +]

+]

Although the captured EV bracketed images can be used to fine-tune exposure, we prefer using them for HDR photography. To do this, we download the three or five bracketed exposures to our computer and use HDR software to combine them into a composite image. With tone-mapping software, we can alter the color and contrast to produce images with surreal colors. This differs from the camera’s built-in Auto HDR function, which renders a more realistic image without extreme coloration.

The bracket shooting technique overcomes the sensor’s limitations through image processing. A single exposure concentrates on the midtones in a scene; therefore, a bright sky may be overexposed and deep shadows may be underexposed. In the case of the Bracket order command set to [0![]() —

—![]() +], the first shot records the camera’s optimum exposure (figure 6-13a); the second shot records detail in the highlights (figure 6-13b); and the third shot records detail in the shadows (figure 6-13c). The final composite HDR image shows detail in both the highlights and the shadows (figure 6-13d).

+], the first shot records the camera’s optimum exposure (figure 6-13a); the second shot records detail in the highlights (figure 6-13b); and the third shot records detail in the shadows (figure 6-13c). The final composite HDR image shows detail in both the highlights and the shadows (figure 6-13d).

Figure 6-13a: Optimum exposure

Figure 6-13b: Underexposed by 2 f-stops

Figure 6-13c: Overexposed by 2 f-stops

Figure 6-13d: Combined image using HDR software

Another option when bracketing exposures is the icon BRK followed by S: Single Bracket. This is the same as the Cont. Bracket except instead of having the camera firing all the shots automatically with one press of the shutter button, you will have to press the button repeatedly to take the sequenced shots. This is the difference between a semi-automatic rifle, which fires one bullet with each squeeze of a trigger, and a machine gun, which spews out a series of bullets while the trigger is depressed once.

Bracket WB and DRO

The Drive Mode bracket commands, WB Bracket and DRO Bracket, are unusual in that they work from a single shot and create three images with adjustments that are below normal, normal, and above normal. Both Bracket commands have two options: [Lo] and [Hi]. [Lo] applies a small degree of bracket adjustment and [Hi] applies a large degree of bracket adjustment.

These commands are not disabled when you save files as RAW and JPEG file types, but when using Image Data Converter, we saw DRO and WB effects applied to only the JPEG images. If you use these commands and save in [RAW&JPEG], you will save six files: 3 RAW and 3 JPEG. This may be a bug in the camera software. It may be corrected in later versions of Sony’s firmware, or it may not be a problem if you use a different RAW converter. Theoretically the effects of DRO and WB could be applied to the RAW files, but we did not find this to be the case while testing the functions of this camera.

Recommendations

Manual operation of the camera is for those who want to obtain the best possible exposure and focus. When compared to using the automatic modes, manual operation is admittedly slower, but it provides advantages that are otherwise unattainable. For example, if you need exposures longer than 30 seconds, you will have to use M mode.

If you use a tripod, M mode is a natural match. You might think that modern cameras have made tripods obsolete, but this is not the case. If you are a nature photographer working with long telephoto or macro lenses, tripods are invaluable. The weight and magnification of a 400mm telephoto lens makes handholding the camera difficult. The stability and precise controls that a tripod provides help you to focus and frame your pictures precisely. At the other end of the spectrum, close-up or macro photography also benefits from using a tripod. You will find the stability of a tripod essential for precise framing and focusing. Even if you are a scenic photographer, a tripod can help you work with your kit lens. It will give you the availability to spend more time composing your image and concentrating on ensuring that the subject is in sharp focus.

For our work with telephoto and close-up lenses, we rely on MF mode. We’ve found that when the depth of field is small, AF mode often fails to lock onto the subject, and instead has the tendency to focus on intervening objects, such as twigs or branches.

When we are shooting an assignment, we do not like using the menu commands. It simply takes too much time to scroll through all the commands before you find the one you need to change. To speed up the process, we use the Fn button and Quick Navi screen. To use the latter, make sure the [For viewfinder] data display format is checked in the DISP Button>Monitor command. This format displays all of the camera settings instead of showing a live view of the subject. When you press the Fn button, the screen gives you a portal to alter most of the camera’s displayed settings.

When shooting outdoor scenes, we turn off AWB and set WB to one of the preset values. For example, when photographing sunsets, we find the reds to be more saturated when we set the WB to daylight rather than AWB. When working indoors with incandescent lighting, we use Custom WB. We do not use the fine adjustment of colors in the camera; instead we work with the saved RAW file on our computer.

When taking movies, we leave DRO set to [DRO Auto] in order to lighten dark shadows. If you decide to use one of the Lv options instead, we recommend you experiment with different degrees of DRO and find the one that suits your photography best. For our still photography, we felt DRO Auto’s effect was insufficient by itself and we dialed in an Lv of [4] or [5]. Our feeling is that DRO is difficult to use within the camera because you have to estimate its effects prior to taking the picture. We prefer lightening shadows in a picture by post processing with Image Data Converter. It is easier to obtain the effect we want by post processing the saved image. Image Data Converter provides a convenient means to create DRO-like effects on our still photographs. Similarly, we prefer using Photoshop for altering the contrast in our image. Although it does not have a DRO option selection, we find that by selecting areas of the image and using layers, we can generate an image with a satisfactory appearance.

We have tested Sony a7/a7R’s Auto HDR function and achieved very good results. However, we are old-school camera users and still prefer generating HDR images by bracketing and combining the multiple RAW images in our computer with third-party software. RAW format gives us the most recorded data for maximum post-processing capability. We load the images in third-party software, such as Photomatix. After the photographs are merged, we use this software for tone rendering. We recommend that you run two tests to see which you prefer: (1) generate an HDR image with the camera’s Auto HDR function, and (2) generate an HDR image of the same subject with third-party software.

Using the Auto HDR function is simple and quick, but it is not the same as capturing the images and generating the HDR image yourself. We again recommend that you play with the exposure compensation when working with this tool. We take the extra step of using exposure bracketing and third-party software. In part, this is for obtaining better control in the final picture. Not only can you vary your effect with tone-mapping software, but also, you have a greater range of settings to work with if you save in RAW. Auto HDR can only be saved as a JPEG.