Have you ever worked or dined in a restaurant that has a swinging door in and out of the kitchen? Have you ever pushed (or watched someone push) on that door when another body is trying to get through from the other direction? What happens?

You push, they push, and nobody gets through.

5 DEMONSTRATE COMMUNICATION STRATEGIES

There's only one way to understand the other person's story, and that's by being curious. Instead of asking yourself, ‘How can they think that?!’ ask yourself, ‘I wonder what information they have that I don't?’ Instead of asking, ‘How can they be so irrational?’ ask, ‘How might they see the world such that their view makes sense?’ Certainty locks us out of their story; curiosity lets us in.

—Douglas Stone, Bruce Patton, and Sheila Heen, Difficult Conversations

Primary Purpose

As the individual sessions continue, your purpose in Chapter 5 is to combine centered presence with key communication strategies in order to change the parties' adversarial dynamic and help them communicate more effectively.

Preparation

- Know the purpose and desired outcome for the session.

- Know which skills you will focus on and why.

- Have scenarios in mind for role-playing and practicing the skills.

- Read your notes from the previous session.

- Enter with optimism for a positive outcome.

Agenda

- Express appreciation for the individual's presence.

- Explain your hopes for the session and ask what the individual hopes to gain.

- Ask for any new developments since the last session.

- Teach communication strategies and skills, employing examples from the conflict at hand.

- Discuss ways to prepare for the next session and set a date.

- Take notes and send them in a follow-up email after the session.

- Assign homework.

Conduct a Learning Conversation

Faced with the choice between changing one's mind and proving that there is no need to do so, almost everyone gets busy on the proof.

—John Kenneth Galbraith

Most of the time, conflict is set in motion by differing needs, views, values, and/or thinking or behavioral styles. Without experience or training in conflict skills, we often don't know how to ask for what we want, communicate a contrary viewpoint, say no, or express the impact of a coworker's action. When we're unskilled in conflict, we either avoid it or become overly direct and confrontational.

And although we may not have received specific training in conflict and communication, our culture is a powerful teacher. You only have to look around to see how our families and workplaces, schools and unions, corporate and government leaders, friends, neighbors, teachers, and public figures usually deal with conflict and differences. The message? Conflict is a contest that I should stay clear of or win, an unpleasant experience with lasting consequences, or a clash of beliefs that can turn violent. Living in this environment of reactivity, most of us have seen opposing views, frustration, and irritation bottled up or expressed belligerently or positionally—especially in the workplace. Instead of having a dialogue with the person we see as the source of the irritation, we hold back, talk ourselves out of it, or express the frustration to others, creating an unhealthy dynamic that feeds on itself.

In the case of workplace conflict, what the parties need are skills to help them talk to each other and role models who demonstrate learning conversations instead of message-delivery monologues. A learning conversation is exactly that—a conversation in which the primary purpose is to learn:

- How does my partner in the conflict view this situation?

- What am I missing?

- How am I contributing to the conflict?

- What are possible solutions?

Once you learn enough by asking questions, listening, acknowledging, and expressing yourself in this purposeful way, you find a way to solve the problem or, barring resolution, decide how to proceed with respect for each other's differences.

As a coach, your presence and practice with these skills help your employees feel safer discussing what they haven't been able to address in the past as well as show your employees what it looks like to be curious, open, and in an inquiry mode. In aikido fashion, you facilitate the release of this pent-up energy in skilled ways and toward a positive purpose.

The Difficult Conversation

In conflict situations, we're used to witnessing—and often participate in creating—“difficult conversations” instead of “learning conversations.” In fact, we are so schooled in that expression that our mindset is programmed to think only of the difficulty we might encounter—not the learning. I'm talking about the conversations we know would be helpful to have, but we leave for another day or, worse, we hold them reactively and ineffectively.

Dozens of well-written, well-researched books, illustrated with compelling real-world examples, have been written about difficult conversations. (You'll find these listed in the Further Resources section at the back of the book.) You may already be familiar with some. If not, I encourage you to choose a title, read it, and decide if you will incorporate its suggestions in your process.

At the same time, we know changing habits requires more than just reading. Real, transformative change of the kind we're talking about happens through experimenting, exploring, and experiencing the benefits—exactly what these individual sessions offer.

As a coach and a participant, I've found it also helps to have a checklist of strategies and practices to refer to. Over the years, in my own research, teaching, and training, I've observed certain best practices that show up time and again. They include:

- Knowing your purpose for the conversation.

- Inquiring, listening, and learning.

- Acknowledging what you're hearing.

- Informing, advocating, and educating.

- Building mutually agreeable solutions.

To simplify these concepts for ease of recall and use, I created the 6-Step Checklist.

The 6-Step Checklist is short enough to remember under stress and blends the central teachings from this extensive field into a list of action items on how to turn a difficult conversation into an exchange of ideas. The 6-Step Checklist Worksheet in Appendix E guides you through the steps in conjunction with a specific conversation.

The 6-Step Checklist

- Center. Prepare for the conversation with centered reflection. Re-center periodically during the conversation.

- Purpose. Clarify your purpose for the conversation.

- Inquiry. Enter with an open and curious mindset. Ask questions to uncover your partner's point of view.

- Acknowledgment. Let your partner know you've heard them.

- Advocacy. Be clear, direct, and respectful in stating your point of view.

- Solutions. Listen for and encourage possible solutions that emerge from the conversation. Follow up.

Steps 1 and 2—Center and Purpose—are the necessary under-pinning for any learning conversation and the reason we focused on them exclusively in Chapter 4. Here in Chapter 5, we focus on the three steps that represent the action of the conversation: Inquiry, Acknowledgment, and Advocacy. We look at Step 6, Solutions, in Chapter 7—where we also bring all six steps back together for review, practice, and use in the joint sessions.

In the individual sessions, you're sharing a conflict resolution model and using it to coach the parties through specific conflict scenarios that have stalled the working relationship. In the joint sessions, they'll use the checklist to uncover mutual goals and areas of agreement.

In most difficult conversations, people want to be heard before they listen, which is why we start with inquiry.

Understanding as a Goal

Have you ever dined in a restaurant that has a swinging door in and out of the kitchen? Ever pushed (or watched someone push) on that door when another body is trying to get through from the other direction? What happens? You push, they push, and nobody gets through.

The same push-pushback phenomenon occurs when two people want to get their differing viewpoints across at the same time. It usually sounds something like, “Yes, but you're wrong because . . .” or “No, you weren't listening. What I'm trying to say is . . .” and so on. If you want to get through to the other side and they're not creating an opening, you either let them talk first or push hard enough to get them to hear you. If we extend the metaphor, the more you force, the more they resist. When you push for your way, you virtually guarantee failure because the harder you try to persuade, the harder the opposition will do the same. He wants to be heard just like you.

Inquiry is a powerful skill in your coaching conversations because it helps the parties understand that in order to be heard, they must also be curious, ask questions, and listen. In other words, understanding is the goal—not getting their point across. When they try to understand their conflict partner's view, they create an opening for their partner to do the same. The door swings and they receive their partner's energy, beliefs, and vision, while benefiting from a peek at an alternate reality. They're able to see both views simultaneously while reflecting on how differently their partner perceives the world from the other side of the door. A vivid visual and physical example of this principle is the aikido entry technique known as tenkan. (See the sidebar Aikido Off the Mat: Tenkan).

Inquiry

In Step 3, you're helping the parties discover the power of changing their mindset from being certain of a position to being curious and open to learning.

In aikido, when my partner moves toward me, I physically move off the line of attack. This first step protects me. Off the mat, in daily life, I similarly move from certainty to curiosity when I center myself. This inner self-defense move takes me to a new position, where I'm protected. I can view whatever my conflict partner says from a safe place. Their words don't “hit” me in the same way. In more familiar words, I don't take their words personally.

Now that I'm off the line, I can observe where the attack is coming from and where it's going. When I move this way, I can see how to connect with my partner, add my energy to theirs, and guide it to a safe outcome.

Inquiry does the same thing. Asking questions is blending, or adding my energy to theirs. It puts me in the powerful position of learning where my partner is coming from. I hear their intention, hopes, and values. Inquiry also defuses any conflict energy my partner is holding, such as anger and fear, allowing this emotional intensity to find a release valve. Even off the mat, in life, I literally move my body perpendicular to my partner's so I can stay connected to the conversation, while I watch their emotional energy go by and dissipate without affecting me.

Secrets to being in inquiry include:

- Clearing your mind.

- Listening with full attention.

- Making eye contact.

- When thoughts stray (“I wonder what's for dinner?”), bringing them back to the speaker.

- Asking questions you don't know the answer to (“What was the most difficult part of that for you?”).

- Helping the speaker reflect on their thinking (“When I offered to help, did it seem like I was being critical?”).

- Proceeding as if you're attempting to solve a puzzle (“What if we tried this?”).

- Pretending you don't know anything about how they see things (you really don't).

- Trying to understand as much as possible about your partner and their point of view. How do they see the situation? What's the impact of your actions on them? What do they really want for themselves? For this process? For their work?

- Watching their body language and listening for the unspoken (what are they not saying?).

Teach the parties that what their partner says is how their partner sees things; they're entitled to their view. This reminder helps both parties avoid taking any of the other's comments personally. Help each reframe their partner as a tour guide on a visit to an unfamiliar world. That's how they see it? Fascinating! In this phase of the checklist, both parties are trying to learn as much as possible.

Acknowledgment

Too often we assume that we either have to agree or disagree with the other person. In fact, we can acknowledge the power and importance of the feelings, while disagreeing with the substance of what is being said.

—Douglas Stone, Bruce Patton, and Sheila Heen, Difficult Conversations

Acknowledgment is possibly the most underutilized communication skill and the secret sauce that turns difficult conversations into learning conversations. You will forget this. Your employees will forget this. I forget it all the time. But acknowledgment changes the conversation—and the people in it.

Without acknowledgment, all you have is another “Yeah, but . . .” conversation. Even if the parties listen well, if they don't demonstrate that they're trying to understand their partner's meaning and intention, their partner won't feel heard and, consequently, won't be able to listen in return.

Acknowledgment answers three important questions your partner has:

- “Do you hear me?”

- “Do you care?”

- “Are you trying to understand?”

Examples of acknowledging and clarifying statements include:

- “What I hear you saying is . . .”

- “It sounds like . . .”

- “That sounds important. Can you say more?”

- “I'm sorry my action had that impact on you.”

- “What specifically would you like me to do differently?”

- “Can you describe what I do or say that makes me appear aggressive (passive, not interested, angry, and so on)?”

- “I'm hearing concern for the project. What areas are you most concerned about?”

- “From what I gather, you're hoping . . .”

- “Thank you for this information.”

- “I appreciate your thinking on this.”

- “Is there anything else?”

Because acknowledgment demonstrates a willingness and ability to reflect back a view or thought process that is different from—and possibly in opposition to—our own, acknowledgment makes a powerful statement. It says, “I heard you, I'm trying to understand, and this is the meaning I'm making out of what I heard.” It shows respect and a disposition toward resolution.

Acknowledgment takes practice. It's not something we see often. In my own difficult conversations, I try to understand my conflict partners well enough to make their case for them. When I can do this, I know I've understood their point of view.

Contribution Versus Blame

The concept of acknowledgment makes sense. It seems simple, yet it's so infrequently practiced that we have to ask, “How do you teach a person to want to see and acknowledge someone else's point of view?” It's especially challenging when the view seems diametrically opposed, or when one person doesn't like the other, or has decided the other intends harm. It helps if we see the conflict as the result of contributing factors.

In conflict, we're predisposed to blame (making someone else responsible for the problem) and justification (not seeing our own contribution). Falling into this mindset is easy to do and feels good, because I can pretend I'm in the right. The problem, however, is:

- Blaming doesn't solve the problem and discounts my contribution to the problem.

- When I blame or justify, I give up my ability to influence the other person.

- When I give up my ability to influence the other person, I lose power over the outcome.

The concept of contribution solves this dilemma. It isn't them or me; it's both of us, and maybe others as well. What are the contributing factors to this conflict? How has each party helped this situation to evolve? A relevant example is our scenario with Lauren and Susan:

- Early on in the conflict, before we started working together, Lauren and Susan were continually annoyed with each other. However, neither person said anything about what was bothering her, preferring to avoid a possible confrontation. They began to blame each other, instead of acknowledging their individual contributions of avoidance and blame.

- They each had allies they talked to when they wanted to complain about the problem, which was easier than going to the source. These side conversations contributed to the problem and expanded the negative effects of the conflict to the rest of the office.

- Lauren and Susan judged their counterpart negatively, and created a story about her behavior instead of becoming curious and inviting dialogue.

- Consequently, Lauren and Susan each behaved according to the story they invented about the other: “Susan refuses to help me, so I'll stop asking” and “Lauren doesn't want help; she'd rather do it alone and get the credit.”

There may be external contributing factors as well:

- Lauren's and Susan's teammates colluded in the conflict by engaging in gossip with and about them.

- Cultural or system norms included managers who wanted to avoid conflict and keep the peace at all costs.

- Task-oriented managers applied pressure for the parties to focus on work and not take things personally, but did not help them work on the relationship.

- Lauren's and Susan's learning and behavior styles clashed.

Regardless of the reason, the twin traps of blame and justification always lead to more of the same—if we don't know we have other choices.

The good news is that we can use blame and justification as red flags—indications that we're abdicating the only power we really have in conflict. Instead, by choosing to take responsibility for our words and actions, we can change what's not working in the situation and intentionally influence it for the better. In other words, we can notice and change our contribution to the problem. Additional content and applications of the contribution versus blame model can be found in Difficult Conversations: How to Discuss What Matters Most, by Douglas Stone, Bruce Patton, and Sheila Heen.

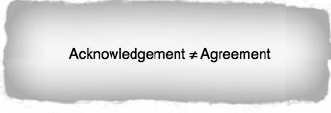

Acknowledgment ≠ Agreement

Another reason it can be hard to acknowledge other people's points of view is that we associate acknowledgment with agreement. The good news is that the parries can learn to keep the two separate. For example, when a speaker says, “This sounds really important to you,” it doesn't mean the speaker agrees with the statement, only that the speaker hears that the statement is important to their partner.

In other words, acknowledging is not agreement; it's simply repeating back to the speaker what you heard and asking clarifying questions. For example, you can acknowledge but not agree by following up with language such as:

- “I'm not sure I agree, but I'd like to hear more about your point of view.”

- “I have a different take on this but would really like to hear why you feel so strongly about it.”

Inner Acknowledgment

The parties can also acknowledge their own feelings of anger, annoyance, confusion, and personal defensiveness when they arise.

For me, the process usually starts with an awareness of physical tension—my jaw tightens or I notice I've stopped breathing. In an argument with a coworker over who should take the lead in a training initiative, I said, “Wow, I just got really irritated by that comment, and I think I'm becoming defensive. Can we stop for a moment? I just want to talk about this topic. I'm not trying to persuade you in either direction.” The acknowledgment helped both of us to re-center.

Advocacy

The parties in this conflict will need skills to help them say what's on their mind. This is advocacy. When we advocate, we're assertive. We're saying, “Here's what I see. It may not be how you see it, so I'm going to put the view out there in such a way that you can see it through my eyes.”

Advocacy is also standing up for something—a point of view, value, or belief. In conflict, that view can be different from someone else's. It's why conflict is usually conceptualized as a push-pushback archetype, and why inquiry and acknowledgment are such valuable skills.

There are ways to advocate for a position without offending or causing defensiveness. When an individual can advocate in this way, it increases his or her chances of being heard in a conflict. When helping your employees express their viewpoints, needs, and beliefs, certain strategies improve their chances of being heard.

Wait . . .

When advocating a position, it's common to not really listen to what the other person is saying but instead jump in with our perspective too soon. “Yeah, but . . .” is so ingrained in our verbal repertoire it often pops out automatically. If the speaker you're saying that to isn't finished presenting their point of view, they won't hear you. I sometimes play a game with myself to see how long I can wait and how much I can discover about the other person before I begin advocating for my message. It's great practice, and often brings to the surface interesting information and useful insights.

Continue to Clarify Purpose

Remind the parties to continually clarify the purpose of the conversation—their own and that of the other person. What are they really trying to accomplish? Do they want to win the argument, punish their partner, or solve the problem? Focusing on purpose takes participants back to a centered and positive intent.

Don't Assume

It's tempting to assume the other party knows what you're thinking, or that the person should know. Consequently, the parties in your conflict may begin a statement in the middle of a thought without considering whether their partner is aware of their thinking. Remind your employees to tell their side of the story in a way that doesn't make assumptions about what the other person knows or agrees with.

Educate

Because each person's view is unique, your employees need to educate each other on what the world looks like from their window.

Sheila Heen, coauthor of Difficult Conversations, tells the story of a car trip with her two-year-old son. He's in his car seat in the back. When Sheila stops at a traffic light and asks how the traffic light works, her son says, “We go on red and we stop on green, Mommy.” He's quite adamant about his view, despite Heen's explanation about how the red-light/green-light system actually works. She's stumped until they arrive at their destination (also at a lighted intersection). She exits the car and goes to the back door to extract her son. Upon leaning in to lift him out of his car seat, she happens to notice that the only view he has is from the side window. He can't see the traffic light in front of the car; he can only see the traffic light on the side street. In his view of the world, we do indeed go on red and stop on green.

Heen's example is simple and poignant. We don't see what they see. They don't see what we see. How can we help each other see through our window? How can we possibly solve a problem without listening for their view and educating them about ours?

Share Facts

Sharing facts is often referred to as the I-Message or I-Statement:

- The Fact (“When you didn't arrive at the agreed-upon time . . .”)

- The Feeling (“. . . I was concerned.”)

- The Hope (“My hope was for your safety and well-being.”)

- The Request (“Next time you're going to be late, can you call to let me know?”)

A simple assertiveness tool, the I-Message can help both parties share what's happening from their experience without blame or judgment.

The problem is that we often frame “facts” subjectively. “When you ignored me this morning . . .” begins with an interpretation of a situation. The fact may be that the other person innocently walked by without speaking. But we immediately formed an interpretation—“You ignored me”—without realizing it.

Chris Argyris, author, professor, and thought leader in organizational learning, developed a tool called the Ladder of Inference to visually demonstrate how we form interpretations and draw conclusions from available data. At the foot of the ladder lies the data: “You walked by me this morning without speaking.” As we move up the ladder, we get further from what actually happened and more deeply into our story of what happened. At the top of the ladder is the conclusion we draw: “You purposely ignored me.” Usually, we start the conversation from our conclusion. If I assume you're ignoring me, I can easily draw a conclusion that you will be difficult to work with.

However, the model also suggests that by being specific about what actually happened—“When you walked by my desk and didn't say anything . . .” —we can climb down the ladder and more accurately describe the data available to us at the time.

Although the Ladder of Inference may seem to be a simple technique, it takes practice to become proficient in using it. And my experience is that the practice delivers untold benefits in helping us grow into more honest, respectful speakers.

As you work with your employees, help them understand that advocating a point of view isn't telling or selling. It's helping someone else stand in our shoes. It's tempting to assume my partner should know what my shoes feel like, especially if I've waited too long to hold the conversation. If I have, I might start by acknowledging that, as in, “I'd like to talk with you about something that's been bothering me. I think this will help us go forward on this project. And I admit, I should have brought this up sooner.” This approach also acknowledges my contribution to the problem becoming more entrenched.

After mastering inquiry and the efficient use of questions, the partners in conflict will grow in their ability to address the problem through advocacy because they understand their partner's hopes and needs as well as whether they see the situation in similar or different ways.

In the joint sessions, you will help both parties clarify their needs and hopes without minimizing their partner's. In one joint session that I held, one of the parties was able to advocate in this way:

From what you've told me, I can see how you came to the conclusion that I'm not a team player. And I think I am. When I point out problems with a project, I'm thinking about its long-term success. I don't mean to be a critic, although perhaps I sound like one. Maybe we can talk about how to address these issues so that my intention is clear?

Notice the aikido metaphor at work—the blending (“From what you've told me, I can see how you came to the conclusion that I'm not a team player”) and the redirecting (“And I think I am”).

Intent and Impact

When I'm teaching, I talk in terms of intentionality. As we've seen, our intention is almost always positive. We have the best motives, and yet sometimes the intention is received negatively. The impact is not what we intended.

The ability to distinguish between the intent of an action and its impact is useful in learning conversations, and has been helpful in my own practice. In Difficult Conversations, Douglas Stone, Bruce Patton, and Sheila Heen note that we often make assumptions and create stories about another's intentions based on the impact their behavior has on us. Usually, we assume the worst. For example, if I feel intimidated, I assume you are trying to intimidate me.

Scenario: You're my teammate, and in a team meeting, you tell me that I missed a key element in creating a new spreadsheet for a project update.

- Your intent: To help me learn the spreadsheet software and create a positive outcome for the team.

- The impact on me: I feel inadequate. I see you as critical and trying to look good in front of the team.

A useful strategy is to entertain the possibility that the impact on me might not be what was intended. Imagining a positive intent allows me to field the feedback differently. I can listen with an open mind, take what works, and leave the rest. And, if the delivery was harsh, I can offer feedback of my own.

When you coach the parties in offering feedback, ask them to think about whether their partner is criticizing or trying to be helpful. Being aware that their coworker's intent may be different from its impact, an employee can describe the impact without blaming or becoming defensive. For example:

Thanks. I appreciate knowing what I missed. And I know your intent was for me to learn the software so we can be successful. Next time you have that kind of feedback, could you give it to me privately?

The aikido metaphor is revealed again in the blending (“I know your intent was for me to learn the software so we can be successful”) and redirecting (“Next time you have that kind of feedback, could you give it to me privately?”).

Other possible ways to advocate in the spreadsheet scenario might include:

- “Can we talk? When you gave me that feedback about the project spreadsheet, I felt awful. I'm sure it wasn't your intent, but the impact on me is that I felt called out in front of the team. Next time, I'd appreciate it if you came to me privately.”

- “In my experience, the content of the spreadsheet is more important than the way it's displayed. Tell me if you see it differently.”

- “Do you have a minute? I've been holding on to something that's been bothering me, and I think I've made it worse by not mentioning it when it first happened. Last week, when you said . . ., I took it badly. I thought I'd done a good job, and your remarks were uniformly critical. I'd like to know if you saw anything that was positive.”

- “When you stand over my desk, I get nervous. I need time to collect my thoughts. Please let me finish the report, and then we can talk about it.”

In each of these examples, the speaker advocates for what they want in a clear, direct, and respectful way.

With this model, you can help your people imagine likely positive motives behind the actions of their coworkers, giving others the benefit of the doubt and making it easier for employees to express themselves and their message.

Finally, knowing the difference between impact and intent helps people lead into an advocacy message with a positive intention. For example:

When you said you would have the budget ready Tuesday, I took you at your word. My intention is that, as a team, we recognize the importance of deadlines on a project as time sensitive as this. Can you tell me what happened and what we can do to remedy the situation?

Model Respect

As people perceive that others don't respect them, the conversation immediately becomes unsafe and dialogue comes to a screeching halt. Why? Because respect is like air. If you take it away, it's all people can think about. The instant people perceive disrespect in the conversation, the interaction is no longer about the original purpose—it is now about defending dignity.

—Kerry Patterson, Joseph Grenny, Ron McMillan, and Al Switzler, Crucial Conversations

We model respect when we listen for understanding, refrain from making assumptions about others, speak without blame or justification, and recognize that the listener can't know what we're thinking, feeling, or telling ourselves about the world around us. Our view of the world may be—and often is—completely different from theirs. Your employees also have completely different views of the conflict they're in. Respect looks like inquiry, acknowledgment, and advocating in a way that doesn't trample on the right of others to have their own views.

In her book Teaming, Harvard professor Amy C. Edmondson explains “naive realism,” a phrase coined by psychologist Lee Ross in the 1970s as the human tendency to believe that “I alone am privy to the true reality.” In other words, this “invariant, knowable, objective reality” is so obviously true that anyone who doesn't see reality as I do is clearly unreasonable and/or irrational. One outcome of naive realism is that we tend to think everyone believes the way we do, and has similar beliefs and values. Social psychologists call this the false consensus effect. For example, someone might say, “Everyone knows our education system needs serious reform.” My sister—an award-winning fifth-grade teacher—might not agree with that statement. And were she to question it, the speaker would perhaps consider her biased, unaware, or worse.

Naive realism and the false consensus effect are about respect or, in this case, disrespect. As a coach, it's important to notice and bring forward when one of the parties makes a statement about a view of reality that their partner may not hold. When the conversation is respectful, both parties feel safe talking about almost anything, and this is the result you want.

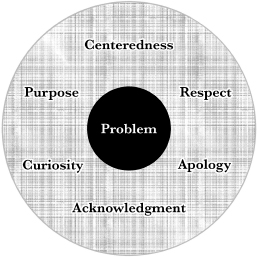

If the parties are worried about emotions derailing their best efforts, I find it helpful to redraw my graphic of two concentric circles. This time the smaller circle in the center represents the problem were trying to solve. The larger outside circle is a safety net that demonstrates positive intent and makes it easier to talk about difficult issues. These practices are foundational for a learning conversation:

- Curiosity

- Purpose

- Centeredness

- Respect

- Apology

- Acknowledgment

In the book Crucial Conversations, Grenny, McMillan, and Switzler use a similar diagram that includes a third outer circle containing the words “silence” and “violence.” You can help the parties know when a conversation is becoming psychologically unsafe by increasing their ability to notice when one of them shuts down (silence), or becomes sarcastic or demeaning (violence).

When they notice the conversation is moving toward one or the other of these extremes and becoming “difficult,” they can bring the conversation back to a “learning” frame by employing one or more of the elements of the outer circle in the diagram—centering, asking helpful questions, listening with curiosity, and reiterating the purpose of the conversation. For example:

I'm noticing how easy it is to get emotional about this issue, and I'd like to reinforce our purpose—to build a more cohesive work relationship. I'm sorry if I've been talking too much. Please tell me again how you think we could interact more effectively together on this project.

Remember that by using the 6-Step Checklist, your employees are building:

- A readiness to see and acknowledge the other person's humanity and point of view.

- The capacity to manage and express emotional energy purposefully.

- The ability to listen for understanding.

- Skills to turn their opponent into a partner for problem-solving.

In my experience, it usually takes between two and four individual sessions of about an hour each to complete the teaching, application, and transfer of the skills necessary to prepare the parties to meet jointly. The number of sessions depends on how many of the concepts you teach, how well the parties integrate the concepts in their workplace interactions, and how you perceive the parties' readiness and ability to move forward into the joint sessions.

Practice

- Role-play. A useful practice in the individual sessions is role-play, or “real play,” as a colleague calls it. Choose a few typical difficult interactions and play out conversations using the 6-Step Checklist. You play one role and let your employee play the other. Then switch roles so they can practice both sides.

- Ask your employee what they think the other person's feelings and needs are around this conflict.

- Ask your employee to become aware of when their attitude or behavior toward the other party begins to shift.

- Ask what assumptions they might be making about their partner and invite them to challenge those assumptions.

Before you leave, set a time for the next session. Send a follow-up email with a summary of your notes and suggested homework to be accomplished before the next time you meet. A day or two before the next session, send a reminder email.

We turn now to Phase 3. It's time to bring the parties together. Our purpose in the individual sessions has been to build the parties' skills, confidence, and understanding. As you listened to their stories, you found areas of agreement, confusion, and curiosity, as well as similarities and differences around desired outcomes and expectations.

The quality of being and communication skills you shared have prepared each party to talk to the other in ways they couldn't in the past. And the homework, reading, and self-awareness activities you've engaged in have laid a foundation both parties will use to assemble a new and more resilient relationship.

Homework Examples

- Managing Conflict with Power & Presence Workbook: Review through page 20.

- Read “Abandon Blame: Map the Contribution System” in Difficult Conversations.

- Read “Create a Learning Conversation” in Difficult Conversations.

- Read “Make It Safe” in Crucial Conversations.

- Look for ways in which you contribute to positive or negative outcomes in the workplace. Bring stories to our next session.

- Watch for the Ladder of Inference at work in your relationships. Bring examples to the next session.

- Look for opportunities to interact respectfully, saying “Good morning” and “Thank you,” and smiling often.

Key Points

- Combining a centered presence with key communication strategies helps to change the parties' adversarial dynamic.

- The 6-Step Checklist offers a succinct summary of best practices for changing a difficult conversation into a learning conversation.

- Inquiry is an attitude of openness that grounds the conversation in problem-solving and defuses conflict energy.

- Acknowledgment says, “I heard you, I'm trying to understand, and this is the meaning I'm making out of what I heard.” Acknowledgment shows respect and a disposition toward resolution.

- Acknowledgment moves us from a blame frame to a contribution mindset.

- Acknowledgment does not equal agreement.

- Advocacy skills help the parties say what's on their minds, stand up for a value or belief, and help their partner see their point of view.

- The ability to distinguish between the intent of an action and its impact is a useful tool in advocacy.

- If the parties have engaged with curiosity, centered intent, respect, and honesty, solutions present themselves.

Sources

- Difficult Conversations: How to Discuss What Matters Most by Douglas Stone, Bruce Patton, and Sheila Heen

- Thanks for the Feedback: The Science and Art of Receiving Feedback Well by Douglas Stone and Sheila Heen

- Unlikely Teachers: Finding the Hidden Gifts in Daily Conflict by Judy Ringer

- Crucial Conversations: Tools for Talking When the Stakes Are High by Kerry Patterson, Joseph Grenny, Ron McMillan, and Al Switzler

- Teaming: How Organizations Learn, Innovate, and Compete in the Knowledge Economy by Amy C. Edmondson

- The Fifth Discipline by Peter M. Senge