CHAPTER 6

Analyzing the Buyers

Generic structure, as we discussed in Chapter 1, primarily relates to the logic of proposals. Unless you’re selling equations to a logician or theories to a scientist, however, logic is rarely enough. That’s why you’ll have to use more than logic. You’ll have to give me, your potential client, more than technical expertise or a logically constructed methodology, more than elegant-sounding résumés or qualifications statements that I know look pretty much the same in every proposal you prepare. You’ll have to convince me that I want to work with you.

Think about what you offer to me: you often don’t know what you’re going to make (i.e., what you’ll deliver to me) until you make it. You operate more like a medical doctor than a civil engineer. An engineer designs a bridge to span a river, while a doctor creates, tests, and re-creates hypotheses to discover something unknown, something hidden, and perhaps something not agreed to. Accordingly, to choose you as my “doctor” I need to develop trust that you, your team, and your firm can address my uncertainty, my often ill-defined, even illogical current situation. In such cases, attitude or “bedside manner” is just as important as or even more important than expertise.

You see, although you may think we know each other well, we don’t—certainly not during our initial meetings. I don’t know or probably trust you completely or appreciate your complex personality. And you, certainly, don’t know me completely or know how I will respond in a given situation. In some situations, I become extremely analytical, seeking a lot of evidence, asking a lot of questions, and behaving methodically and systematically. This orientation toward information and reasoned, rational analysis may be based on the risk or magnitude of a potential decision I must make. In this situation, I might desire a detailed methodology (perhaps even your sharing of your logic tree).

In a different situation, I become more concerned about people and their relationships within my organization. This more supportive orientation is one I often take during implementation projects in which I must convince others in my organization to change. In this situation, therefore, I may desire your sensitivity, your care for the personal and developmental concerns of me and others.

At yet other times, especially when I’m dealing with a future issue, one that is often ill defined, I become more concerned with ideas and hypotheses and creativity. This orientation leads me to rely more heavily on intuition and feelings. Therefore, I may desire from you a more conceptual and open-ended orientation.

Finally, in yet other situations, I become more assertive, more oriented to action, more desirous of control. I may adopt this directing or controlling orientation when I sense urgency and the need for rapid change or a forceful response. I become more task-oriented, more insistent on getting something accomplished quickly. Therefore, I may desire from you a certain assertiveness, a far more proactive orientation.

So even if you think you know me because you’ve seen me operate in one kind of situation, you may be surprised at my response in another situation. Your task is to make reasonable and educated guesses about the nature of my likely response so that you, in turn, can respond to my situation and convince me that you understand my organization’s problems or opportunities and that we can work together successfully.

Additionally, if I’m not the only one making the buying decision (which is almost always the case), you also need to know my colleagues on the evaluation committee, how they perceive the situation, and what they like and don’t like about the scope and range of potential solutions, as well as their relationship to me, and mine to them. Would you be surprised to hear that we may see the situation differently, have different selection criteria, and even have different biases? Well, more often than not, we do. So you and your team need to deal with me and each of my colleagues. This can be a very complex interchange.

Miller and Heiman’s Four Buying Roles

Let me recommend a book to you that isn’t at all about writing but is about selling (and that’s what your proposal process needs to do: sell). The book, The New Strategic Selling,1 contains a powerful method for analyzing the members on a buying team. Each of these individuals, in what Miller and Heiman call a “complex sale” (i.e., one with multiple decision influencers), plays one or more roles: economic buyer, user buyer, technical buyer, or coach.

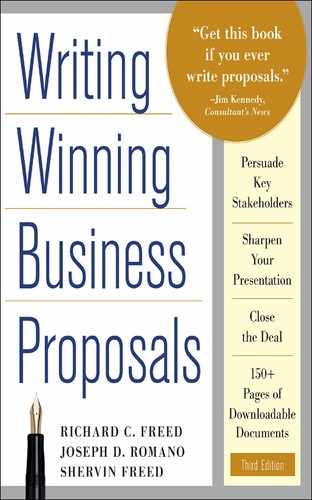

The economic buyer (only one exists in most selling opportunities) has direct access to and control of the budget, discretionary use of those funds, and veto power over the sale. This buyer’s focus is primarily on the bottom line and on the impact the project will have on the organization. Figure 6.1, briefly summarized and adapted, is Miller and Heiman’s description of the economic buyer.

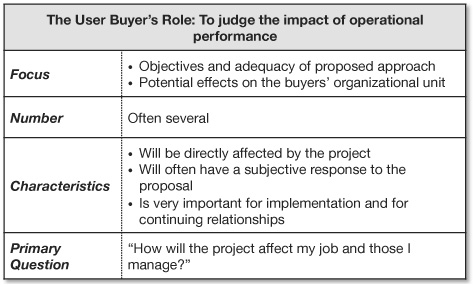

I have played the role of economic buyer, and I have also been a user buyer (see Figure 6.2), focusing primarily on the project’s potential day-to-day effect on my own area of responsibility or organization. If I am a user buyer, you’d better not ignore me if you want a long-term relationship. If, by chance, you sell an initial project that circumvents me, I may sabotage subsequent projects or even hinder acceptance and implementation during the initial one. That is the case because your project will have a direct impact on my job performance and on those I manage. If I’m a user buyer, you’d better convince me that the winds of change are pleasant or, if they’re not, that the hurricane will at least clear out a lot of unwanted dust and debris, leaving me as one of the survivors.

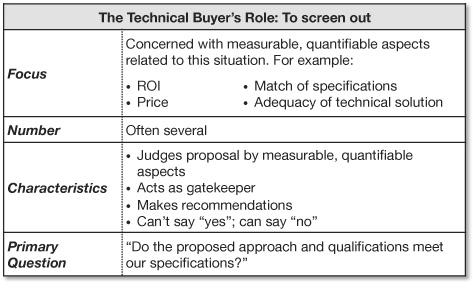

I also might be a technical buyer (Figure 6.3), who primarily judges the measurable and quantifiable aspects of your proposal. If so, I’m a gatekeeper, making recommendations to the other groups of buyers. As a technical buyer, I don’t usually have the authority to accept your proposal, but I can play a decisive role in eliminating you from further consideration.

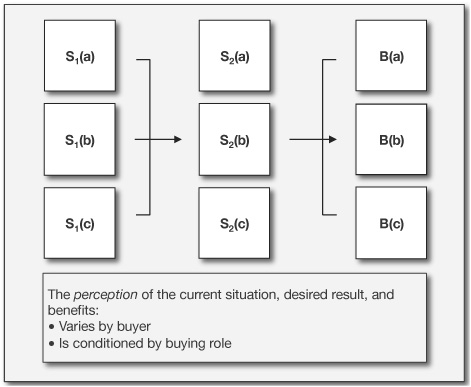

The fourth buying role is the coach (Figure 6.4), an individual (or individuals) whom you hope to find and develop to help you make the sale. It’s highly desirable to have a coach or coaches on the buying team. It’s ideal, of course, if one of your coaches is the economic buyer.

Why do you need a coach? Well, sometimes you don’t. But often you do, probably more often than you realize. You see, sometimes I don’t fully trust you. I don’t know you well enough for you to have earned my trust. In fact, if you’re a consultant, as I stated earlier, I often would prefer not having you or other consultants around, asking me a lot of time-consuming questions and prying into my affairs. You are an outsider, and I would prefer that you stay that way. I wish that I didn’t need you and that I could resolve my own organization’s issues. But even though I might need you (you still have to convince me), I’m not likely to reveal everything. I might not believe that what you need to know from me is actually worth your knowing. Even those things I’m reluctant to tell, you might forget to ask, and you might not have another opportunity to do so. Or you may never even have the opportunity to meet me at all, because I’m too busy to see you or I judge you too unimportant to see.

FIGURE 6.3 The technical buyer

This is where your coach (or coaches) comes in. The coach may be able to arrange introductions with me or with other buyers on my team; identify buyers you have overlooked or normally would not be able to identify; elaborate on our evaluation criteria; provide advice and counsel about selling strategies and maybe even the competition; and, in general, act as a guide and confidant during the selling process. Although coaches often can help you indirectly by arranging introductions and providing intelligence, sometimes (as an experienced consultant and friend of mine explains), they can actually help you sell. As my friend tells the story:

A young fellow who is an internal consultant for a company I was trying to sell invited us in a competitive situation to talk about inventory. We had a long meeting with him and then a long second meeting, and then we had to write a proposal to go with him to his boss. I hate that kind of situation. We never met his boss; all we knew was that his boss is a hard-charging, young, very creative guy who, like all the other top people at XYZ, shot up in the organization. And I said, “Does he like presentations, or does he like written documents?” The internal consultant said, “He gets annoyed at too many words and things; he likes creative presentations.”

So I put together a presentation with about 25 pages, a little flip-chart thing that I would put on the boss’s desk, so I was totally in control. It was mostly cartoons and all kinds of wild stuff, a lot of meaning and very few words. The last cartoon showed a boat with the captain leaning over the bow. On the captain were the words “XYZ Management.” In front of the boat were a bunch of icebergs. On the tops of the icebergs, I wrote things like “reduce inventory” or “cut inventory costs,” and on the bottoms, I wrote phrases like “destroy customer confidence.” At the very top of the cartoon, I wrote, “Our objective is to steer you through these icebergs, avoid some of them, go right through others because they are so small that they don’t make any difference, and show you where to set dynamite charges to get rid of the really bad ones.”

Now the internal consultant asked me for a copy of all this in advance, so I sent him a letter, giving him the philosophy of what we were trying to do. Word by word, I explained that whole last cartoon. At the meeting, I flipped through the charts and when I came to the last one, I said, “It’s sort of like icebergs,” and then paused. Suddenly, the internal consultant said, “Yes, as a matter of fact . . . ,” and he just took over, independently quoting right from my little personal letter to him, which really was the proposal. Now, he looked smart. His boss liked it, and we got the job. If he wouldn’t have said anything, I would have kept talking. But we made him part of the creative team without soliciting it. He could be part of our team, which he wanted to be; he could be smart in front of his boss, and be selling to his boss.2

Coaches (at least in their coaching role) are interested in the strokes or recognition or visibility they will get from helping you make a successful sale and thus initiating a project that proves valuable. They will gain recognition or visibility, get strokes, or be seen as problem solvers if they have played a part in your selection and were therefore instrumental in helping to choose the right firm that eliminated pain or capitalized on opportunity and therefore allowed results to be delivered and benefits to accrue.

A Fifth Buying Role

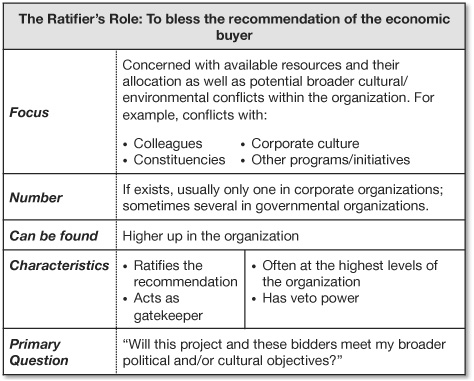

Would you believe that I might not select you even if your firm scored the highest number of points on our evaluation scale? Even though you would “beat” the second-place finisher by two to five points, you (and not they) would place second; they (and not you) would win. In many of those situations, you will lose because a fifth buying role—the ratifier—strongly prefers someone else.

A ratifier doesn’t exist in all selling situations, and when one does, the ratifier isn’t an official member of the selection committee. The ratifier is, however, consulted by the economic buyer to approve or bless the selection committee’s decision. In the ABC situation, for example, there might be a ratifier at Consolidated, an individual from whom Ray Armstrong normally would seek approval before selecting a consulting firm. Even if Paramount Consulting were ranked highest by ABC, Armstrong might want to have that choice blessed by the ratifier. And the ratifier could say no—because she has a poor opinion of Paramount, because she has a better opinion of one of the other competitors, or simply because she wants to play it safe by going with a higher-profile or better-known firm. If the ratifier refuses to bless ABC’s decision, the selection committee very well may have to continue its deliberations.

In the role of blessing the recommendation of the economic buyer, the ratifier wants to be certain that the proposed project (and the proposers themselves) meets the ratifier’s broader political and/or personal objectives and desires. As such, the ratifier is most concerned about the potential cultural or environmental conflicts within the organization. He or she wants to know, as Figure 6.5 shows, whether the project or proposers will cause conflicts with colleagues, with the organization’s culture and constituencies, or with other projects then being or soon to be undertaken.

Note that in using the various categories of buyers, Miller and Heiman aren’t talking about individual people but about roles people on the selection committee play during the selling situation. An economic buyer, regardless of whom he is personally, individually, is always concerned about your proposed project’s bottom-line impact on the organization; therefore, he focuses on return on investment (ROI) or good budget fit or increased productivity. A user buyer, regardless of title, is always concerned about your service’s day-to-day impact on her department’s operation; therefore, she may focus on the ease and effectiveness of implementation or on improved efficiency.

The real significance of these different orientations is that individuals playing each of the roles will expect different kinds of benefits than will others playing a different role. Allow me to emphasize this last point. Because you, I, and everyone else buys because of benefits, you must recognize that we have different expectations about how we will each benefit from your proposed approach and results. We aren’t really buying your product or service; we are buying what that product or service delivers—benefits. Therefore, the major reason that you want to identify buyers’ roles is this: You will better be able to identify how they, as opposed to their organization, will benefit from your engagement. That’s why the first cell of the Psychologics Worksheet,3 which will be discussed in this chapter’s work session, focuses on:

![]() the individual buyers and the role(s) they play

the individual buyers and the role(s) they play

![]() the perception of benefits the buyers, based on those roles, believe will accrue to them

the perception of benefits the buyers, based on those roles, believe will accrue to them

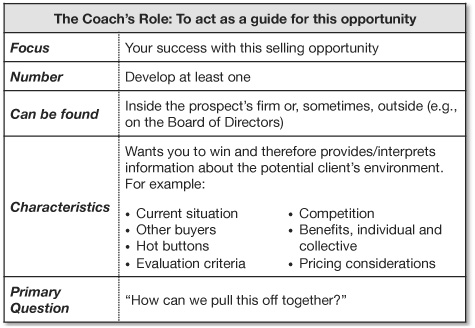

When we discussed the baseline logic in Chapter 2 and Chapter 3, we did so from the perspective of my organization, my firm. But organizations don’t buy your services; I and my colleagues do. And I and my colleagues have different perceptions of S1 and S2 based upon the role(s) we are playing in this selling situation. As a result, the simplified baseline logic that I used in Chapter 3 needs to be revised when you are considering the psychologics rather than the logics, when you are considering the people rather than their firm. Chapter 3’s simplified baseline logic would be adequate only if you were selling to a one-person buying team with that single individual playing all the buying roles. Because this situation almost never occurs, the formula must be expanded, as depicted in Figure 6.6.

This second formulation is much more realistic (and strategic) for three reasons:

1. The perception of S1, the current situation, and of S2, the desired result, varies by buyer and is conditioned by buying role. Never assume a groupwide or firmwide perception of the current situation. S1 refers to individual pain, uncertainty, or opportunity. The difference between one person’s perception of S1 and S2 is the distance she must go to eliminate her pain or realize her opportunity. The distance her fellow buying committee members must travel is likely different, because they start from different points, have different orientations, and travel a different terrain. Individual perceptions of S1 might be different because, obviously, people are different, with different needs, desires, responsibilities, and perspectives. What to one person might be a problem in customer service might be a problem in sales effectiveness to another. What to one person might be perceived as increased inefficiency might be seen as eroding profits by another.

FIGURE 6.6 Different buyers, playing different roles, will have different perceptions of the current situation and the benefits they, individually, expect to receive.

2. Regardless of individual perceptions of the current situation, definable agreed-upon results, S2, will eliminate everyone’s perception of S1. Therefore, the importance of getting right the overriding question and objective. If all parties agree on the project’s objective, they will be able to visualize a future situation in which their current pain or their existing opportunity is addressed.

3. The perceived benefits accruing from buyers’ perceptions of S2 will vary by buyer and by buying role. If S1 is an ineffective information system and S2 is the implementation of an effective one, the user buyer may benefit from increased versatility and efficiency; the economic buyer, from increased efficiency, yes, but primarily as it affects profitability; the technical buyer, from obtaining more sophisticated state-of-the-art capability and functionality.

In Chapter 7, I’ll begin to show you how to convince me and each of the other buyers that you and your firm are better, more convincing, and more responsive than anyone else. This persuasion will take you a giant step toward gaining the two to five points that make the difference between winning and losing. Before that, you need to read the following work session, which identifies the buying roles played by individuals on ABC’s selection committee and the benefits that will accrue to each once the plan is developed and after it’s implemented.

CHAPTER 6 REVIEW

Analyzing the Buyers

To begin to analyze the buyers:

1. Classify the members of the buying team according to the role or roles each will play in making the decision. Each single buyer can play one or more of four possible buying roles: economic, user, technical, coach. A buyer also can play the role of ratifier. A ratifier can play only one additional role: coach.

2. Identify each buyer’s perception of S1, the current situation, remembering that that perception will be conditioned by buying role, position in the organization, and personality.

3. Identify for each buyer the individual benefits that will accrue from achieving S2, remembering that those benefits will be conditioned by the buyer’s role, position in the organization, and personality.

4. If at all possible, develop at least one coach.

WORK SESSION 5: Identifying Buying Roles and Generating Benefits for ABC

In your previous work sessions, you focused on the “logics” of the selling situation: the logical relationship among the current situation (S1), the desired result (S2), and the benefits (B) that will accrue, as well as on the logical methodology that will ensure ABC’s transition from its current situation to its desired result. The logics necessarily focus on the ABC organization collectively. You’re not selling, however, to an organization but to people within it, people who will evaluate your proposal through the lenses of their own perceptions, desires, and needs. Now, therefore, you must begin to focus on the individuals on the consultant-selection committee.

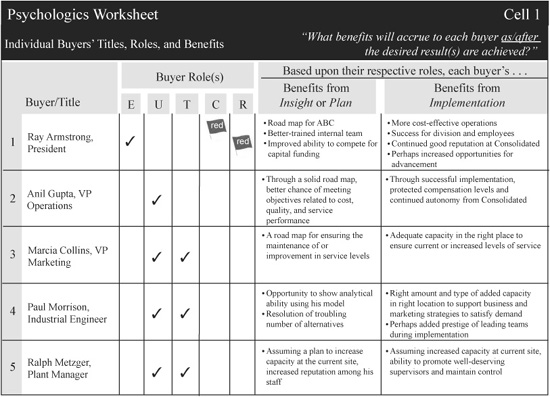

These are some of your thoughts as you review your notes from the initial meeting with ABC’s consultant-selection committee and carefully study Gilmore’s interview notes from his follow-up visit. You consult your Logics Worksheet to review the current situation and desired result (from a collective, corporate point of view). Then you complete Cell 1 of the downloadable Psychologics Worksheet, on which you identify the various buyers, their buying roles, and the benefits each will enjoy from having a plan for increasing capacity, as well as from having that plan implemented in a subsequent engagement.

Ray Armstrong, President

You believe that Ray Armstrong is currently the economic buyer because he will give final approval for the study. You realize, however, that if Armstrong has a budget threshold beyond which he will have to gain approval from Consolidated, then someone at Consolidated will be the economic buyer if your or your competitors’ proposed fees exceed that limit. Not recalling any discussion of this matter and not finding such a discussion in your colleague’s notes, you decide to bring up this issue with Gilmore.

Armstrong appears pleased with ABC’s past and present performance. Success has been heavily dependent on the ability of manufacturing to produce at low cost, with high quality and with a high degree of responsiveness to the needs of ABC’s customers. However, Armstrong’s warning bells are now ringing because the division’s performance probably will deteriorate dramatically within the next few years, when, as marketing’s forecasts show, product demand will significantly exceed current manufacturing capacity. Armstrong has two other concerns, you believe. One is that ABC must decide quickly on the amount and type of capacity needed because lead times for additional building and/or manufacturing equipment are quite long, perhaps six to twelve or more months. A second concern is that however ABC decides to provide additional capacity, its plan must be thoroughly documented and justified. The plan must be understandable, logical, and convincing to Consolidated, which will have to evaluate the ROI and provide capital funding for the expansion.

Armstrong desires that the consultant’s study quickly shows ABC how to provide the capacity it needs by defining the amount and type of capacity required, identifying and evaluating various alternatives for providing that capacity, and documenting the results of its analysis in a report and possible presentation that will convince Consolidated of the need for and the viability of the additional capacity.

When S2 is reached, Armstrong believes he will have a road map that will show ABC how to get where it wants to be and a report that will help persuade Consolidated to release the necessary funds. To date, Armstrong has a good reputation with the parent company, and he would like to keep that reputation, you believe, for at least two reasons: first, to increase his chances of getting future requests approved, and second, possibly, to increase the likelihood of his own career advancement. You have no hard evidence in this regard, but your research about his employment history indicates that Armstrong’s ambitions could take him higher than the presidency of the ABC Division. For these reasons, the outcomes of your potential study will be critically important to Armstrong. Your analysis of Armstrong’s buying role and benefits is shown in the first row of Figure 6.7.

FIGURE 6.7 The Psychologics Worksheet, Cell 1, completed

Anil Gupta, Vice President of Operations

You clearly see Anil Gupta as a user buyer because he has overall responsibility for manufacturing operations and because the study will recommend the best alternative for increasing capacity. Your notes indicate that Gupta has concerns about adding that capacity at the current site because the available space may not be adequate for expansion. Furthermore, even if sufficient space were available, Gupta believes ABC would be vulnerable by having the majority of manufacturing resources centralized at one location. Gupta also suggested the possibility of adding capacity at the satellite sites, although he expressed some doubt that all of ABC’s expansion needs could be provided there. Recognizing the wide range of possible expansion alternatives and the capital-intensive nature of the proposed project, Gupta knows that they need a thorough and convincing study.

As vice president of operations, Gupta has the responsibility for producing quality products at competitive costs and for meeting customer delivery requirements in a timely manner. With inadequate capacity, delivery performance will deteriorate, quality could suffer, and costs could rise because of overtime and schedule interruptions to meet rush delivery dates. Gupta’s expectations from the study are rather straightforward: He wants the consultants’ analysis to produce a well-documented, convincing plan for providing additional capacity. For him, achieving S2 means that he and his manufacturing team will have a comprehensive plan for providing the additional capacity in the most advantageous manner. Your analysis of Gupta’s buying role and benefits is shown in the second row of Figure 6.7.

Marcia Collins, Vice President of Marketing

You conclude that Marcia Collins is a technical buyer because she wants to make certain that the study’s methodology uses customer-service levels as a criterion for selecting and evaluating the expansion alternatives. By doing so, Collins believes that customer service must be maintained or improved after additional capacity is implemented. She undoubtedly will also play the role of user buyer because the results of the study will most certainly affect her marketing function and her desire to gain market share. At present, Collins is anxious to see that additional manufacturing capacity is provided to remedy the shortfall that her forecasts predict in just a few years. Without that additional capacity, service levels will deteriorate. She also believes that capacity should not be added at the present site for two reasons: first, because of the shift in product demand away from ABC’s current location in the U.S. Midwest; second (and, in this, she agrees with Gupta), because with most of the manufacturing resources in one location, ABC could risk its hard-won reputation for excellent customer service if there is a catastrophe or labor stoppage that disrupts production at that location.

Therefore, Collins not only wants the selected consulting team to develop and evaluate various alternatives for adding manufacturing capacity, she would prefer that the team’s recommendation enhance (or, at minimum, not diminish) current service levels. If service levels are used as an evaluation criterion, Collins is confident that the recommended alternative will enable ABC to serve its customers better and contribute to the division’s financial and market performance and, consequently, to her own compensation and career advancement. Your analysis of Collins’s buying roles and benefits is shown in row three of Figure 6.7.

Paul Morrison, Chief Industrial Engineer

Paul Morrison, you conclude, will also play two buying roles. He’s a technical buyer because he will be concerned with the thoroughness and rigor of the proposed methodology. Morrison believes that these qualities will be necessary to address the complex issues involved in selecting the best alternative. Given that he developed the in-house distribution model, he probably will focus on the parts of the methodology that focus on logistics, landed cost, and service levels. He’s also a user buyer because he undoubtedly will lead the ABC project team that will use the study’s results to plan for and implement the new capacity plan. If your study resulted in ABC’s building a new factory, Morrison could become plant manager at that site.

Morrison has expressed several concerns about the current situation. First, although everyone seems to agree that additional capacity is needed, no one has attempted to quantify the amount or its timing. Second, some individuals, he believes, may be pushing their own agendas, advocating expansion alternatives that could be better for themselves than for ABC. Finally, and related to the previous point, he doesn’t believe that the current site will support the additional manufacturing capacity needed (though adding at the current site would be advantageous to others, particularly Metzger). Morrison expects the study to produce specific results: to define the amount of capacity necessary to meet the forecast, to evaluate thoroughly the alternatives both quantitatively and qualitatively, and to produce a recommendation that will enable ABC to provide capacity effectively and expeditiously. Your analysis of Morrison’s buying roles and benefits is shown in row four of Figure 6.7.

Frank Metzger, Plant Manager

You conclude that Frank Metzger is also both a user and a technical buyer. As plant manager with intimate knowledge of ABC’s manufacturing operation, he certainly will be part of the project team that uses the results of the consultant’s study to plan and implement the additional capacity. In his technical buyer role, he probably will examine the methodology closely to determine whether it gives adequate consideration to adding capacity at the current facility.

Metzger is concerned that his operations are already approaching capacity and that as demand continues to grow, he will be forced to operate uneconomically (e.g., with excessive overtime, reduced time to maintain equipment, and higher freight costs). Like others, he agrees that ABC badly needs additional manufacturing capacity.

Metzger is looking forward to reviewing the consulting team’s quantification of ABC’s need for capacity. He is hopeful, however, that the amount of capacity indicated is such that most, if not all, can be accommodated at the existing site, particularly if newer manufacturing technology is utilized. As a result, his managerial responsibilities would increase and he would be able to promote some of his supervisors who have supported him and performed well in the past. Your analysis of Metzger’s buying roles and benefits is shown in row five of Figure 6.7.

Examining Your Notes: What’s Missing?

In examining your detailed notes on each buyer, you now know what you know and, just as important, what you don’t know. For example, none of the buyers, according to your determination, can be considered a coach. This makes you uneasy, given that the situation is competitive and that at least two of your competitors have done previous (and, apparently, good) work for ABC. Those firms could very well have special access to people and intelligence at ABC that you do not and perhaps will not have. According to Anil Gupta, Paramount had been recommended to ABC. That’s what he told Gilmore. But as far as you know, Gilmore didn’t find out who the recommender was. That person could very well be (or be turned into) a coach. You decide to discuss this matter also with Gilmore, and you red flag the Coach column on Cell 1 of the Psychologics Worksheet (as shown Figure 6.7). Just as troubling, none of the five buyers meets the criteria for a ratifier, who could very well exist at Consolidated and who could strongly influence Armstrong’s opinion about whom to select. If you had a coach, you might be able to work with that person to identify the ratifier.

You know that your firm’s win rate is considerably lower when you don’t have a coach (and, chances are, a competitor does), and you also know that even a strong relationship with an economic buyer means very little when an unidentified ratifier refuses to bless the economic buyer’s decision. Accordingly, you also place a red flag in the Ratifier column of the worksheet.