APPENDIX F

Using the Right Voice: Determining How Your Proposal Should “Speak”

Some years ago, I came across a good illustration of rhetorical voice, a writer’s or presenter’s construction of her persona, the character she plays in a particular message.1 When you and I are talking face-to-face, we unconsciously adjust our manner of speaking so that we project the appropriate sides of ourselves to achieve our goals. You don’t speak the same way to me, your potential client, as you do to your spouse or your children or your acquaintances or the taxi driver who delivered you to my door. You project certain aspects of yourself that you want me to see or hear. You speak in a certain “voice.” When I’m reading your proposal, however, you’re no longer there, but your voice is, speaking through the words on the page. If I’ve come to know you as hard-working, ambitious, and fast on your feet, I’d be taken aback if the voice in your proposal were entirely different.

The good illustration I’m referring to came in the form of two drafts of a progress report a consultant shared with me. The consultant was engaged in a five-week feasibility study. Because of the study’s urgency, her proposal had contained a workplan with well-defined deadlines and progress reviews. Despite careful planning, however, after three weeks, the study was three days behind schedule, in part because questionnaires submitted to employees had not been returned on time. Here are two sentences from an early draft:

Earlier Draft: Although we will receive some questionnaires later than we had anticipated, we are tallying those already received. When more responses trickle in, we can simply integrate those data into what we have compiled.

Apparently, the earlier draft’s intention was to communicate a message, to speak in a voice, that suggested the following: “Don’t worry. This isn’t that big a problem, and everything will be all right soon.” The voice might be characterized as “laid back” or “unperplexed.”

After reading her draft, the consultant must have decided that, although the situation might not be problematic to her as the consultant, it might be seen as a big problem to her reader, who was anxious to have the project completed on time. Where she intended “laid back,” the reader might have inferred “lazy.” Where she intended “unperplexed,” the reader might have read “reactive.” So she used a different voice in a later draft—call it “aggressive,” “on top of the situation,” or “proactive.” Even a simple change from receive (which suggests passivity) to collect (which suggests activity) makes a big difference:

Later Draft: Although we will receive collect some questionnaires later than we had anticipated, we are already analyzing tallying those already received. Just as soon as When more the remaining responses trickle in do arrive, we can simply will immediately integrate those data into what we have already compiled.

How important is voice in the proposals you write? Vitally. When I try to decide between your proposal and a competitor’s, I feel like I’m listening to a debate. Each proposal not only presents different content, each “speaks” that content in a different voice as it attempts to convince me. You’re no longer there, but your voice is, even in your absence. What the voice says reveals a lot about your character and your personal characteristics. The voice can project you as sympathetic or hard-nosed, as structured or flexible, as detail-oriented or global. Your written voice shouldn’t be the same from proposal to proposal any more than your speaking voice is the same from situation to situation.

Adjusting your speaking voice is much less difficult than adjusting your written voice. You are well practiced in playing different roles as you speak. You’re not the same to a superior as you are to a subordinate; not the same at the office as you are at a sporting event or a cocktail party. You know, somehow, that in any of these situations you’re still “yourself,” only a different side of yourself, of your many-sided personality. So you don’t think very much—you don’t have to think very much—about how you present different sides of yourself in these different situations. Every day, you play so many different roles, speak in so many different voices, that you’re probably not even aware of doing so.

Despite your being relatively different across different situations, you’re relatively the same in similar ones. This consistency within similar situations is important in many relationships. When someone you thought you knew acts differently than you would have predicted, you often feel that you didn’t really know her at all or that you didn’t know her well enough. This change in behavior might surprise you, and it might even unsettle you.

Consider the common newspaper story of the good husband or boy scout who, beyond anyone’s prediction, turns out to be a bigamist or mass murderer. Those events make news because they’re so surprising and unsettling. When you try to sell to me your proposal, I don’t want any surprises, either. If I come to know you during our initial meetings as energetic and animated, I’d be surprised by a proposal that’s leaden and dull. If I know you as analytic and careful, I’d be surprised if the proposal’s voice were speculative and incautious. Similarly, if you have established good chemistry and rapport with me but the proposal’s voice is neutral and generic, I’d probably suspect that your proposal is boilerplate and thus that your study will be also. So the “you” that you project during the preproposal meetings needs to be the same voice that speaks in the proposal.

Here’s how one of my friends, an experienced consultant named Donald Baker, strategically adjusted the voice in his proposal to match the image of himself projected during the client call:

Baker had been trying for about four years to secure business with this potential client, a leader in the building-materials industry, so when they finally did need a study done, Baker was the one called in first. And he was the only one called, apparently because Baker convinced the company president that the consultant’s firm “wouldn’t scare the daylights out of” the divisional vice president with whom Baker would be working.

The company’s president was a dynamic, aggressive, Harvard graduate. Although the proposal was addressed to him, the primary decision maker was the divisional vice president. Unlike the president, the vice president was not at all polished. He had worked in the mills all his life, was practical and direct, and did not wear a jacket to work. The decision was the vice president’s because the company was “totally decentralized.” The president had told Baker that if the vice president said yes, he would say yes (though the vice president did not know that). Thus, Baker needed to write a proposal responding to the vice president’s practical sensibilities, but he also wanted the document to be responsive to the action-oriented president, who had never before seen Baker’s work and whom Baker wanted to impress for whatever future business might be in store.

To respond to the vice president’s needs, Baker used a lot of straight talk, telling him what specific deliverables he would have at the end of the study and how the resulting cost savings would end up paying for the project. Thus, Baker expressed a strong bottom-line orientation: “The proposal, almost by its nature, had to have some boring recapitulation of data that really is not even relevant to the study such as costs and numbers of workers and how big the plant is and how they were organized over the years.” Moreover, Baker used headings such as “Sales Effectiveness,” “Customer Service,” and “Organizational Effectiveness” rather than generic headings such as “Background” or “Methods.” He did not “want to sound like a heavy consultant” but rather wanted to place himself in a “sort-of-good-ol’-boy kind of role.” In addition, since the vice president was a Southerner whose plant was located in a small deep-South town, Baker brought with him to the meetings a highly experienced colleague who spoke with a strong Southern accent.2

This example not only illustrates how Don Baker strategically projected the right voice for a given situation, it also suggests how he adapted his document to respond to that situation because he fully understood his relationship to his readers, his buyers. The questions Baker asked and the answers he received while meeting with the prospect helped him determine what image to convey, what voice to speak in, to satisfy the needs of his readers to make them feel comfortable and persuade them to accept the proposal.

You might have noticed that I have been using adjectives to characterize a specific voice, like proactive, laid back, analytical, or cautious. Other adjectives could be used to describe characteristics of a good consultant, for example, confident, energetic, hard-working, responsible, knowledgeable, culturally sensitive, experienced, organized, efficient, and reliable. As a result, many if not most of your proposals will need to project these attributes. Some occasions, however, will demand that you convey not only these characteristics but also specific attributes that respond to these occasions.

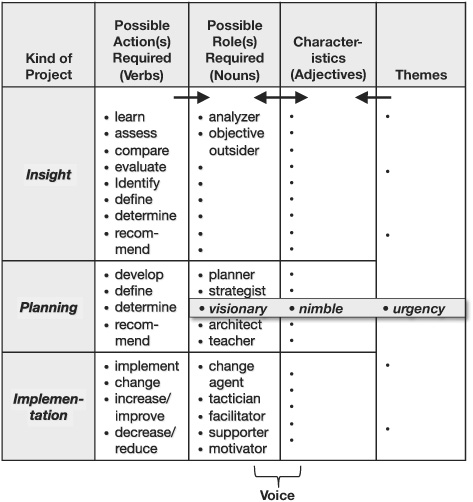

How do you decide which characteristics are relevant, which adjectives to use? Figure F.1 shows you how.

Your voice depends in part upon the kind of project you’re proposing to do because different kinds of studies might require different roles. But defining your role alone isn’t enough. If you are doing a Planning Project for me and I need you to be a visionary, you need to decide what kind of visionary you need to be. That decision depends upon my hot buttons, my selection committee’s evaluation criteria, and your counters to your competition. That is, the decision depends upon your themes.

FIGURE F.1 Your voice, how your proposal “speaks,” is the combination of a noun and an adjective; themes help you derive the adjective.

For example, if one of my hot buttons (and one of your themes) is urgency, I wouldn’t want a visionary who contemplates his navel; I would want someone who can envision a strategy quickly. You would need to be a combination of an adjective and a noun: a quick-thinking visionary, for example, or as Figure F.1 suggests, a nimble visionary. A visionary might do, and perhaps a visionary is what your competitor will be. But a specific kind of visionary may be more persuasive to me, and if you’re capable of being that kind, you ought to be.

In summary, then (and I’m reading right across the columns in Figure F.1), your voice is controlled by the kind of project you’re proposing (first column) and by the verbs related to the results you propose to deliver (second column). These verbs, the overall actions required, phrase your project’s objectives. These actions, in turn, require a specific set of skills common to a specific role or roles (the nouns in the third column). These nouns, however, are further modified (fourth column) by the kind of person you need to project yourself as. These modifying adjectives are regulated by themes (for example, the hot buttons to which you need to respond) (fifth column). The result, the voice you need to convey, is a combination of the nouns in the third column modified by the adjectives in the fourth column.

So to determine your voice, you need to ask three important questions:

![]() Given this kind of project (that is, Insight, Planning, and/or Implementation), what verbs characterize the outcomes, the desired results expressed as your project’s objective(s)?

Given this kind of project (that is, Insight, Planning, and/or Implementation), what verbs characterize the outcomes, the desired results expressed as your project’s objective(s)?

![]() Given that kind of project and those verbs, what nouns (e.g., architect/planner/strategist; tactician/facilitator/motivator) describe the character you should play to best achieve the desired results?

Given that kind of project and those verbs, what nouns (e.g., architect/planner/strategist; tactician/facilitator/motivator) describe the character you should play to best achieve the desired results?

![]() Given that character, what adjectives (related to your themes) describe the characteristics you should convey?

Given that character, what adjectives (related to your themes) describe the characteristics you should convey?

The third question should be asked not just for me but for each member of the selection committee.

Because the projects you propose often require you to work closely with me and my people, within my company’s culture, your proposal’s voice has to demonstrate that you can work with me and my colleagues and adapt to our culture. By consciously defining your relationship to us, you’ll be able to determine precisely how you should “speak” and, therefore, what side of yourself is essential to project in your document. Just as I am a complex personality whom you can’t totally know, you are a many-sided individual whom I can’t completely know. So you must decide what side of yourself your proposal will convey—what personal characteristics and attributes, what persona, you’ll project as your proposal speaks to me and my colleagues on the selection committee.

Once again, we see the importance of themes. Voice is controlled at the word level, by your decision, for example, to use the word receive or the word collect. And your themes not only embody your larger strategy to address hot buttons, evaluation criteria, and counters to the competition; they govern your tactical choices, word by word, so that your document speaks, not with a lisp or a stutter, but fluidly, as it reflects my story and helps me to see how you can become a part of it.