CHAPTER 2

Understanding the Baseline Logic

A lot of people (and I’m one of them) think that too many proposals try to make the simple complex, when in fact what I and many other buyers want them to do is to make the complex simple. So let me simplify what proposals do, or at least what I’d like them to do from my potential client’s perspective. Let’s concentrate on just three things (which, we’ll see in Chapter 3, are related to three of the generic structure slots—SITUATION, OBJECTIVES, and BENEFITS). Figure 2.1 depicts your proposed project (with examples from the ABC case) in a nutshell.

In the beginning is my organization, which is in a condition, a current “state of health,” a current situation—call it S1. This current situation is what is happening today. Perhaps we don’t like this situation because we have a problem that needs addressing or solving. Or perhaps we would like another situation better because we have an opportunity on which we might capitalize. In either case, we desire to change. Or we might be uncertain about whether we like or should like our current situation, and we’d like to know whether we ought to like it or dislike it.

In each of these cases, an actual or possible discrepancy exists between where we are and where we want to be. Therefore, we are willing to consider engaging a consultant to help us, to propose a project at the end of which we will have closed the gap and be in a different, improved state—call it S2—which is what I call my desired result. At that point, our problem will be solved (or on its way to a solution), or our opportunity will be realized (or at least closer to its realization), or we will know whether we even have a problem or an opportunity. In each case, we will have or know something more than we had or knew before. And we will be better off because of it; we will benefit and gain value from reaching our desired result, S2, by the end of your proposed project.

We are here, we want to be over there, and we’ll benefit when we get there. That simple idea needs to function as the baseline of your proposal—and of your thinking about your proposal to me. That idea has a logic to it, a fundamental logic, a baseline logic. And that idea, that baseline logic, needs to drive the argument of your proposal: “You are here, and we understand that ‘here’ is or might not be desirable. You want to be somewhere else instead, which is more desirable. Once we help you to be that somewhere else, you will enjoy the benefits of being there.”

Although all this certainly isn’t rocket science, only a minority of proposal writers understand this logic, and far fewer know how to test for and apply it. Most proposals are illogical at their core because the writers don’t understand the baseline logic, and even when they do, they don’t know how to convey that understanding clearly to me. They don’t know how to take advantage of that logic to increase the persuasiveness of their presentations and documents. Illogical thinking reduces your probability of winning, and, if you should win, it dramatically reduces your likelihood of conducting a successful engagement. This baseline logic—or, if you prefer, this problem definition or analytical framework—is the basis for a meaningful and persuasive exchange of ideas.

Here I should express two cautionary notes. First, there are times when I, your potential client, am not clear about this baseline logic. I’m not clear about my current situation or about where I want to be at the end of your proposed project. When this occurs, and you do not help me achieve clarity, you and I are in a potential lose-lose situation. In this situation, you probably will write a proposal without clear objectives, without clearly defining my desired result, S2, at the end of your project. I might even accept that proposal, but we might both pay a price, often a significant price, during the project. You may not satisfy me, possibly incur a cost overrun, and not develop the long-lasting relationship we both desire.

To avoid this situation and to ensure that your proposal is fundamentally sound, the rest of this chapter, as well as the next, will build on the concept of the baseline logic, show you how to test for it, and demonstrate how you can use it to your advantage.

The second cautionary note: Although I remarked at the beginning of this chapter that I want you to make the complex simple, I have to admit that the relatively simple concept of the baseline logic often is not easy to understand. Accordingly, this chapter on understanding the baseline logic and the next chapter on aligning the baseline logic are not easy going. At times, the reading will be laborious. Sometimes it will even appear redundant because I want constantly to reinforce important points that will help you use the baseline logic, in this chapter and those that follow, to:

![]() Challenge the depth of my thinking

Challenge the depth of my thinking

![]() Clarify my overriding question(s)

Clarify my overriding question(s)

![]() Clarify your project’s objective(s)

Clarify your project’s objective(s)

![]() Articulate and generate benefits

Articulate and generate benefits

![]() Communicate a measurable-results orientation

Communicate a measurable-results orientation

![]() Construct your methodology

Construct your methodology

![]() Define the magnitude of your proposed effort

Define the magnitude of your proposed effort

![]() Identify your necessary qualifications

Identify your necessary qualifications

![]() Make better go/no-go decisions about deciding to bid

Make better go/no-go decisions about deciding to bid

![]() Demonstrate your ability to address thoughtfully what—to me, anyway—is a complex issue

Demonstrate your ability to address thoughtfully what—to me, anyway—is a complex issue

These substantial benefits will accrue to you only after you have mastered the concept of the baseline logic. Although mastery of anything is difficult, it’s essential that you understand the baseline logic. Everything else in Part 1 of this book (and a good deal in Part 2 and Part 3) depends on this understanding, which provides the foundation you will need to win—to gain the additional two to five points, as the preface suggests, that are often the difference between winning and being a close second. So hang in there: I’m going to give you the key that unlocks the mystery of thinking about and writing winning business proposals.

The Three Kinds of Current Situations, Desired Results, and Objectives

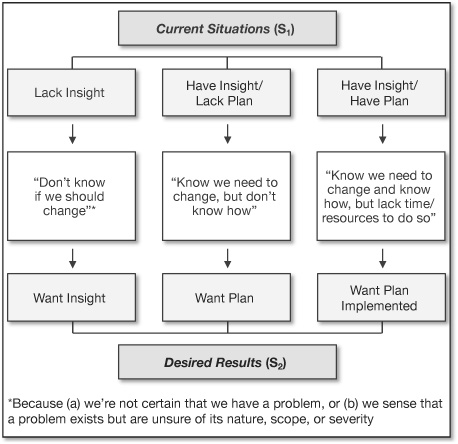

As shown in the first row of the three boxes near the top of Figure 2.2, my current situation can be one of only three conditions. These are the three possible S1 situations that can serve as a starting point for your efforts:

1. I and my organization don’t know if we should change because (a) we’re not certain that we have a problem or (b) we sense that a problem exists but are unsure of its nature, scope, or severity. That is, we lack insight about our situation.

2. We know we should change but we don’t know how, because although we do have insight, we lack a plan to act on that insight.

3. We know we should change and we know how, but even though we do have insight and we have a plan, we don’t have the time or resources to implement that plan.

In Figure 2.2, each of the three possible S1 conditions corresponds to one of three desired results (the lowest row of three boxes near the bottom), and each of these desired results is related to three types of projects you could propose: insight, planning, or implementation. In an Insight Project (the left column of Figure 2.2), I don’t know if my organization should change, so I may desire a competitive assessment or an identification of potential opportunities. Market surveys, benchmarking studies, and audits fall into this category, and your project’s objective could include words such as assess, compare, determine, evaluate, understand, and identify. You provide me insight, which has value because it makes me and my organization smarter and provides a basis for learning whether we need to change.

FIGURE 2.2 The relationship among current situations and desired results

In a Planning Project (the middle column of Figure 2.2), I already know that I need to change, because I have insight but don’t know how to change, so I may desire a plan detailing how my organization should change. Your project’s objective could begin with words such as develop, determine, define, or recommend.

In an Implementation Project (the right column of Figure 2.2), I know that I want to change and I know how to change because I have a plan, but I need additional resources or expertise to implement the change. Therefore, your project’s objective could be to implement, to increase or improve, or to decrease or reduce some specific operational parameter by definable measures.

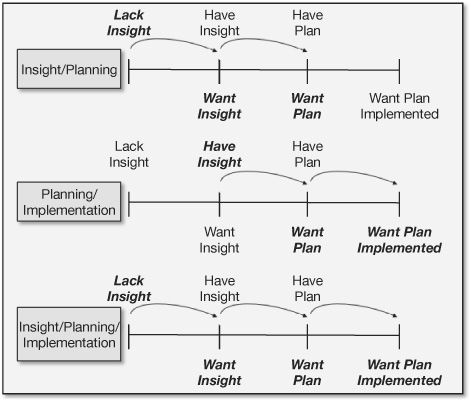

How many objectives your project will have depends on what my current situation is (lack insight, have insight, or have plan) and where I want to be at the end of your proposed project. For example, assume that my S1 state is characterized by lack of insight: I don’t know if we should enter a particular market. Assume that my desired result is to gain such insight. In this instance, you would move me one step, and therefore your study would have only one objective: to provide insight about whether I should enter that market. As Figure 2.3 illustrates, there are three possible combinations of S1 and S2 states that involve a movement of one step and therefore involve only one objective.

In some cases, I might want your efforts to move me two or more steps. Assume again that my current situation is characterized by lack of insight: I don’t know if we should enter a particular market. My desired result, however, might involve more than just insight—I might also want a plan for entering my target market. In this instance, you will move me two steps, and therefore your project will have two objectives. First, you will determine the feasibility of entering the market; second, if entering appears attractive, you will develop a plan for doing so. Here, then, you would propose a two-step project, and a single objective would govern each step. As Figure 2.4 illustrates, there are two possible combinations of S1 and S2 that involve a movement of two steps and a third combination that involves all three steps.

Your proposal’s objective(s) expresses the major outcome(s) of your project. Therefore, it must clearly indicate how far you will take me. As you’ll see in Chapter 5, this clarity is essential if your proposal is to have a logical base on which to build your methodology.

FIGURE 2.3 Projects with one objective

While all this might appear straightforward, let me reinforce the point that I, your potential client, don’t always make it easy for you. I am often unclear in my own mind about what we are trying to do and therefore might unintentionally confuse you. But we’re not here to debate right and wrong. And we’re not here to become better mind readers. We’re here to get agreement on the specific issues to be addressed so that your services will be of the greatest value to me and my organization.

Let’s take the ABC case as an example. Many experienced consultants would believe that ABC’s problem requires a combination study: insight and planning. These consultants would argue that ABC may not need to add capacity in the near term because new equipment and technology, better utilization of current equipment and space, outsourcing, and the like could allow ABC to produce enough product to meet forecasted demand. These consultants would believe, therefore, that two objectives should drive the ABC study: First, determine the feasibility of better utilizing existing capacity. (That’s the insight piece.) Second, if additional capacity is needed, develop a plan for adding it. (That’s the planning piece.) Note the decision point here. If no additional capacity is needed, the second objective may become unnecessary to achieve. If additional capacity is necessary, the second objective needs to be addressed. Combination studies can have such decision points, which occur after a former objective is achieved and before a subsequent one is addressed.

FIGURE 2.4 Projects with multiple objectives

Based on my reading of the case, I don’t believe that ABC is expecting an insight and planning study, and if I were the potential client at ABC, I’d be surprised by a document that proposed one. I might even be suspicious, thinking that the consultants were trying to sell me more than I’d asked for. Of course, the consultants could be correct in their assessment that I need both insight and a plan. If that’s the case, however, they better convince me in our discussions before submitting the proposal. If they don’t, my perception of my desired result will not be aligned with theirs. Those who have had the greatest success with me, both during the business-development process and while conducting the actual project, have made certain that clear alignment exists between my perception of my desired result or results and their own. This alignment is one example of the mutual benefit that should occur during the business-development process.

CHAPTER 2 REVIEW

Understanding the Baseline Logic

1. Proposals contain a baseline logic expressed by S1 → S2 → B:

![]() S1 refers to the current situation. That situation always involves a discrepancy between what is and what could be. Therefore, S1 is characterized by a problem or opportunity and by a lack of benefits. S1 is discussed in the situation slot.

S1 refers to the current situation. That situation always involves a discrepancy between what is and what could be. Therefore, S1 is characterized by a problem or opportunity and by a lack of benefits. S1 is discussed in the situation slot.

![]() S2 refers to the endpoint(s) of the project or phases of the project. S2 is defined in the objectives slot, since your project’s objective(s) is the expression of S2.

S2 refers to the endpoint(s) of the project or phases of the project. S2 is defined in the objectives slot, since your project’s objective(s) is the expression of S2.

![]() B refers to the benefits that accrue to us from achieving our desired result(s). Benefits are identified in the benefits slot.

B refers to the benefits that accrue to us from achieving our desired result(s). Benefits are identified in the benefits slot.

2. The desired result(s) expressed by the proposal’s objective(s) defines the project’s type, of which there are three and only three (excluding combinations):

![]() Insight (e.g., audits, market research, or benchmarking projects). Potential client says: “We don’t know if we should change because (a) we’re not certain that we have a problem or (b) we sense that a problem exists but are unsure of its nature, scope, or severity.” That is, we lack insight about our situation.

Insight (e.g., audits, market research, or benchmarking projects). Potential client says: “We don’t know if we should change because (a) we’re not certain that we have a problem or (b) we sense that a problem exists but are unsure of its nature, scope, or severity.” That is, we lack insight about our situation.

![]() Plan. Potential client says: “We want to change, because we know we have a problem or opportunity or we sense that we do, but we don’t know how to change.”

Plan. Potential client says: “We want to change, because we know we have a problem or opportunity or we sense that we do, but we don’t know how to change.”

![]() Implementation. Potential client says: “We want to change, because we know we have a problem or opportunity or we sense that we do, and we know how to change, because we already have a plan, but we need help to implement that plan.”

Implementation. Potential client says: “We want to change, because we know we have a problem or opportunity or we sense that we do, and we know how to change, because we already have a plan, but we need help to implement that plan.”

If the project combines two or more of the previous elements (e.g., insight and planning), a decision point might exist necessitating a phased study.