CHAPTER 7

Identifying, Selecting, and Developing Themes

Determining What to Weave in Your Web of Persuasion

In Chapter 6, I indicated that if you’re going to write a fully responsive proposal to me, your potential client, you need to do more than meet my buying team’s requirements related to the analytical and technical aspects—the logics—of your proposed support. You also need to respond to the psychologics of our situation, to us, to our individual and group concerns, desires, and needs. I’m not devaluing expertise here. I want it. But you’re not the only expert around. Your expertise is necessary, but it alone is usually not sufficient. So what else do I want?

In addition to expertise, I want a relationship, built on trust, founded on chemistry and rapport, characterized by understanding and assurance. Although I want to be confident about your technical abilities, I also want to be confident about your willingness to serve me, to put me first, to be there when I need you, to answer questions neither of us anticipated during the business-development process. That’s a tall order, but I’m willing to reward you now and perhaps in the future for supporting me in that role.

Let me give you a good example of what I mean. I was once a vice president at RST, one of the world’s largest industrial companies. We were introducing a new organizational concept in all our domestic and foreign factories, an effort that would be extraordinarily complex, involve massive change in the organization, and require a high level of rapport between us and the consultants. We were looking for outside support to work together with us in an ill-defined situation to detect problems, resolve issues, and implement solutions that neither of us could anticipate. The risk was potentially high, and the rewards potentially higher. Nobody had tried this sort of thing before, and, obviously, no consultant had ever tried to help someone do it.

None of this, of course, was lost on the consultant who wrote the winning proposal. Here’s the first major section of his proposal letter. Study it carefully, and you’ll see what I mean.

Our Understanding of Your Situation

During the past few weeks, we appreciated being included in the evolution of your thinking on this difficult project and our potential involvement to help implement your XYZ Cost Concept. This letter concisely describes how we can help you successfully accelerate the worldwide integration.

Over the years, RST has managed its manufacturing on a plant-by-plant basis. As a result, similar and related products were produced using different methods and technology in different locations. For this reason, costs and quality often varied. To reduce variability and costs, you are in the process of establishing integration centers to be responsible for products or related component groups wherever they are manufactured. In other words, each center will be responsible for developing products at the lowest cost and at high quality in order to optimize results.

Each center will be responsible for total worldwide volume for its selected products and for developing a common manufacturing process to improve technology utilization and reduce overhead. In this way, each center will balance design, manufacturing, use of automation, and scheduling. Each will become involved early in the product design effort to set design ground rules to ensure optimum production. Furthermore, each will consolidate worldwide throughput, yields, defect control, costs, inventory, turnaround time, etc., for its product or component responsibility.

Implementation of this concept will be extremely complex. This complexity was emphasized when we reviewed the matrix of centers and locations. Indeed, changes in coordination, measurement and evaluation systems, training, motivation, organizational structure, communications, and control will be significant.

Yet the breadth of these changes is only the first complicating factor. Next is the exceptional magnitude of the change in terms of the number of plants involved, the varieties of locations, countries, and cultures, and the depth of change in your traditional manufacturing style.

In addition, the speed with which the integration will be implemented leaves little opportunity for error. Furthermore, the introduction of the XYZ Cost Concept provides an additional complication of significantly higher product volumes to your company, which is traditionally accustomed to low-volume production.

Finally, no precedent exists for such a complex change except perhaps that which occurred in your own marketing organization.

What this passage has that so many proposals lack is the theme of this chapter, which is themes:

The

Highlighted

Essential

Messages that

Express the character of my

Story

What Themes Are

Themes are the highlighted messages of your proposal because they are repeated and gain force and emphasis through their repetition. They are essential messages because they come from three essential elements of the selling process: my and the other buyers’ hot buttons, our evaluation criteria, and your counters to your competition. As one of the best consultants I know once said to me: “To sell consulting services, your client needs to feel as if the two of you grew up in the same house together”—i.e., that you shared the same history, the same story, and that your proposal expresses the character of that story.

The writer of the RST proposal knew (and knew that I knew) that the effort would be extraordinarily complex, would involve massive change in my organization, and would require a high level of rapport between the consultants and my people as we all worked together to detect problems, resolve issues, and recommend solutions in a situation that was ill defined, to put it mildly. Recognizing that these three ideas (complexity, change, and working together) were key issues to be addressed during the proposed project, he used them (and others) as themes throughout the document.

In the first sentence, he subtly suggests three of the themes we will discuss here:

we appreciated being included in the evolution [i.e., “change”] of your thinking on this difficult project [“complexity”] and our potential involvement [“working together”].

After narrating the past, present, and future of the improved operating concept in the next two paragraphs, he concentrates on two of the themes, beginning with “Yet the breadth of these changes.” From there on, he uses complex, change, and related words 10 times and heightens the effect through parallelism1 (“breadth of these changes,” “exceptional magnitude of the change,” “depth of the change”). He also uses many “additive” transitions (Indeed, Yet, Next, In addition, and Finally) to create a crescendo effect. The flourish comes in the last sentence, which is signaled by “Finally,” underscored in importance by “no precedent exists,” and concluded by a phrase—“complex change”—that uses both themes together.

The writer doesn’t pretend that the task is less than arduous or that he has performed numerous studies similar to this one. Instead, he recognizes my concerns (my story) and makes them his own. He knows that I’m anxious and that my colleagues are anxious, and he even intentionally writes the section to make me anxious, to make me recall my anxiety and the high risk involved. But at precisely the right point, in that last sentence, he compliments my organization by suggesting that if any firm can weather the coming storm, it is RST. Well, maybe RST. “Perhaps” RST. Despite the compliment, he implies that we cannot do it alone; despite our considerable resources and expertise, additional support and abilities are crucial. That support is underscored by the document’s next heading (which I haven’t included). “How We Can Work Together” begins the methods slot, and it continues the proposal’s third theme, “working together.”

By selecting and playing the right themes, then, the writer demonstrates to me that he understands far more than just the logics of my situation. By the time I finish reading the first section of his proposal, he has reinforced the qualities I saw in him during our several hours of preproposal discussions: his sensitivity to the complexity of human organizations (including mine) and the cultural shocks resulting from change and his ability to work with me and my people constructively and competently to implement change. As a result, he increases his and his organization’s credibility. He makes me an accepting rather than an objecting or rejecting reader, one much more inclined to agree with his proposal’s later discussions of objectives, methods, qualifications, costs, and benefits. And those discussions, like this one, are certainly not boilerplate, nor were they written by a junior “just-happened-to-be-available” consultant who never met me. Clearly, the writer developed his themes specifically for my situation.

Where Themes Come From

You’re selling not in a vacuum but in response to my specific situation. That situation is conditioned by what the buyers, individually and collectively, on the one hand, and your competitors, on the other, bring to it. Therefore, you must (1) address the individual needs and desires of me and each of the other buyers, (2) respond to our collective needs and desires, and (3) counter your competition. These three actions provide you with the three sources of themes: hot buttons, evaluation criteria, and counters to the competition, which I’ll discuss in turn (Figure 7.1.)

FIGURE 7.1 Themes come from hot buttons, evaluation criteria, and counters to the competition.

Hot Buttons

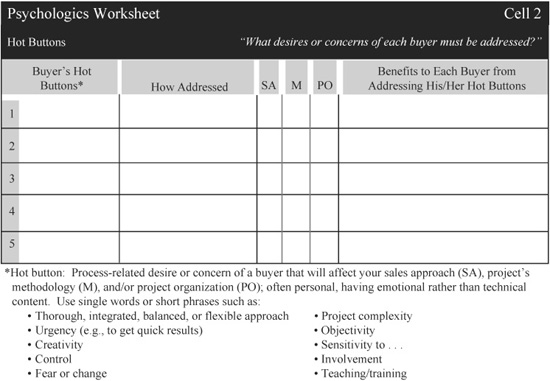

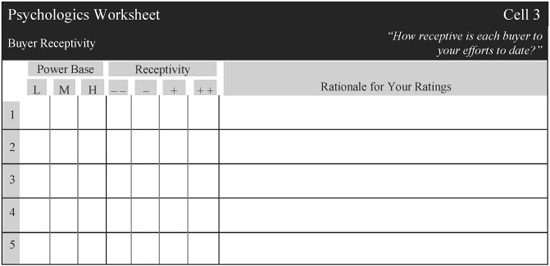

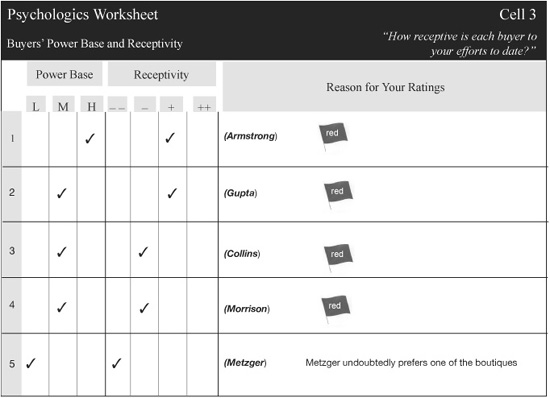

Hot buttons (Psychologics Worksheet, Cell 2; see Figure 7.2) are needs and desires of individual buyers that can be addressed during your face-to-face meeting with me and other buyers, by altering your project’s methodology, and/or by changing your project’s team. Hot buttons are almost always psychologically oriented and process oriented. For example, in the RST excerpt, complexity happened to be one of my hot buttons. I was concerned about the complex nature of the project, about all the possible pitfalls, including those I could see and those that I couldn’t see at the time but knew would present themselves. Complexity, then, wasn’t a result of the study, but it was an issue from my point of view that had to be addressed strategically during the study. Therefore, the writer built into his proposal’s methodology specific tasks for managing the study’s complexity. And he conditioned my response to that methodology by convincing me, in his proposal’s opening section, that he understood the complex nature of our undertaking.

Addressing hot buttons is extremely important in selling your services because your recognizing and acting on my hot buttons significantly helps build the trust and chemistry essential to building a good business relationship. Also, using hot buttons offers you a further advantage: They help you generate additional benefits for your proposal. The following little stories suggest how.

Several years ago, my spouse and I had our house remodeled by people we would never hire again. Their expertise or craftsmanship wasn’t at issue—they did a fine job at what we hired them to do. The way they did it, however, caused us unnecessary time, frustration, and anger. In a word, they were slobs. They tracked mud inside, failed to control the dirt and dust, and even left cigarette butts on the floor. As a consequence, my spouse and I returned from work every evening with more work to do: mopping, vacuuming, and, most strenuous of all, controlling our tempers. The problem wasn’t with the “what” (their expertise) but with the “how” (the application of that expertise). If we were to remodel our house again, the contractors bidding on the job would be confronted with our unmistakable hot button—call it neatness or cleanliness or just plain consideration.

Note that two effects would occur if the contractors would have addressed that hot button, neither of which involves their technical approach to addressing our problem. First, they would alter how they work for us (assuming, of course, that they weren’t already paragons of neatness). Second, we would benefit from that alteration: We would be saved both time and aggravation.

Here’s another, but similar, situation. You know how to drive your car, and you know a bit about how your car works, but you don’t know very much about how to fix it. So when your car doesn’t work, you take it to someone with the expertise you lack. As in some situations where you have little expertise and someone else has a great deal, you have little control and feel quite helpless. Knowledge is power, and, in this case, you have very little of either. When you pay the bill and the expert tells you the problem wasn’t the relatively inexpensive fan belt but the much more expensive starter or alternator, you have no way of evaluating that claim, no way of knowing for certain whether you’re being “taken.” Worse, even if you’re not being taken, you have no way of knowing that you’re not. So when you take your car to a mechanic, you have a hot button—call it trust or honesty or clear communication.

FIGURE 7.2 Psychologics Worksheet, Cell 2: Hot buttons

Again, note that if your hot button had been addressed, two effects would have occurred, neither of which involves the mechanic’s technical expertise for addressing your problem. First, the mechanic would have to change how he works with you (for example, by calling you for approval if the solution turned out to be different from or more expensive than what you anticipated, or by returning to you the damaged part, or by clearly showing you how or why the part was damaged). Second, you would benefit from that change. You would feel better. You’d be less anxious or apprehensive and more certain, not that the car got fixed but that what was wrong got fixed.

I can think of three principles these two stories share:

1. Those without expertise who have to work with those who have it are frequently cautious, uncertain, and distrustful. If I’m thinking about having you do a project for me, I’m doing so because you probably have knowledge, skills, or experience that I lack. Because what you tell me will be based on the knowledge that I lack and that you have, I don’t have the proper framework to evaluate the veracity of your claims.

2. If I have a hot button and you choose to address it, you will have to work with me in a certain way. Quite likely, this means you will work with me in a different way than you would work with another potential client on a similar project. Addressing hot buttons usually affects how you conduct your project.

3. If you do indeed address my hot button, I will benefit. Because my hot button reflects one of my needs, desires, or concerns, I will have that need, desire, or concern satisfied or addressed if you respond to that hot button.

Consequently, for every hot button you identify on Cell 2 of the Psychologics Worksheet (Figure 7.2), you should generate at least one benefit that accrues from your addressing it. Take, for example, one of Ray Armstrong’s possible hot buttons discussed in the work session of this chapter: teaching/training. A solid teaching/training component in the project could be beneficial to him. It could help produce for Armstrong the beginnings of a more competent internal team, one that better appreciates different functional disciplines and has a broader, multidisciplined view rather than a parochial orientation toward company operations.

Evaluation Criteria

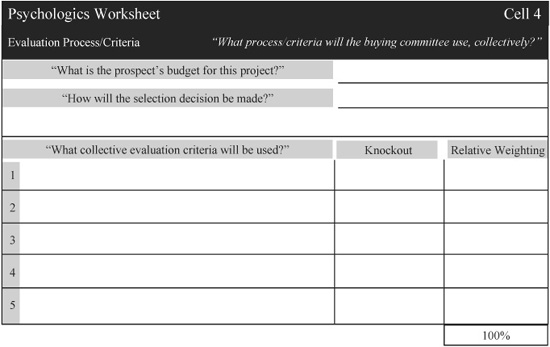

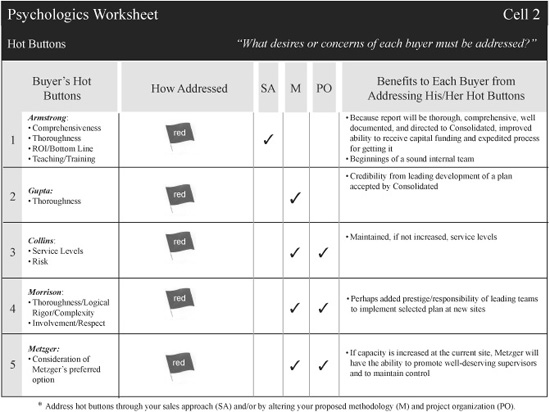

Hot buttons as well as evaluation criteria (Psychologics Worksheet, Cell 4; see Figure 7.3) are used by me and others to evaluate your proposal (and in the case of hot buttons, often subconsciously so). Whereas hot buttons are always individual considerations, evaluation criteria are collective considerations—that is, shared and agreed upon. While most hot buttons have emotional content (involving individual needs and desires), evaluation criteria generally have technical content (involving requirements, specifications, and the like).

That said, it’s important to note that one category of hot buttons does have technical content: the hot buttons of technical buyers. Marcia Collins has a hot button (conditioned by her technical buyer role) related to “maintaining or improving service levels.” In preparing your proposal to ABC, you certainly would want to include the impact on service levels as a hot button. But unless the focus on service levels is shared by all the members of the buying committee, it isn’t likely to be one of the group’s evaluation criteria.

FIGURE 7.3 Psychologics Worksheet, Cell 4: Evaluation process/criteria

Though evaluation criteria are collective and may be written in a request for proposal (RFP), they are not always specified in a section of the RFP that lists and sometimes weights the criteria to be used in evaluating the proposal (see Appendix G on reading and responding to RFPs). The following three criteria were essential to consider in a recent proposal to manage a U.S. hazardous waste program, even though the criteria did not appear in a lengthy RFP:

![]() National consistency: To demonstrate our commitment to accomplishing national goals, consistency in approaches used to set priorities is essential in a decentralized program. The strategic management framework identifies key areas where national consistency is needed to ensure that we are achieving progress in meeting national goals.

National consistency: To demonstrate our commitment to accomplishing national goals, consistency in approaches used to set priorities is essential in a decentralized program. The strategic management framework identifies key areas where national consistency is needed to ensure that we are achieving progress in meeting national goals.

![]() Flexibility: Flexibility in setting program priorities is key to the regions and states closest to environmental needs. The strategic management framework must preserve regional and state flexibility while assuring progress toward national goals.

Flexibility: Flexibility in setting program priorities is key to the regions and states closest to environmental needs. The strategic management framework must preserve regional and state flexibility while assuring progress toward national goals.

![]() Trade-offs: We cannot implement the entire agenda at once. Strategic management planning recognizes the need for trade-offs. We all must articulate these trade-offs and ensure that we make informed and defensible decisions about the resulting environmental and programmatic impacts.

Trade-offs: We cannot implement the entire agenda at once. Strategic management planning recognizes the need for trade-offs. We all must articulate these trade-offs and ensure that we make informed and defensible decisions about the resulting environmental and programmatic impacts.

The previous list wasn’t called evaluation criteria at all, but “Principles governing strategic management of the program.” However, these principles were used in evaluating the proposal, and the proposers certainly could have used themes such as consistency and flexibility to increase the persuasiveness of their document.

Two final notes about evaluation criteria. First, as Figure 7.3 indicates, you should try to weight the evaluation criteria even if they haven’t been weighted in an RFP. As we’ll see below, you will be better able to select your themes if you indicate the evaluation criterion’s degree of importance. Second, you should designate which criteria are “knockout.” Sometimes called threshold criteria, knockout criteria are those that you must meet or you will be eliminated from the competition. One example of a knockout criterion could be “Must have an office in Kuala Lumpur.” If you do, you’re in the running. If you don’t, you’re knocked out of the competition.

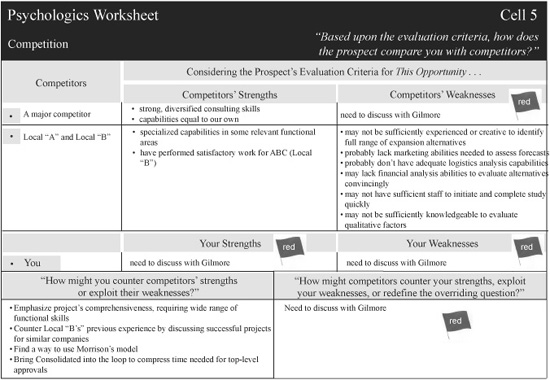

Counters to the Competition

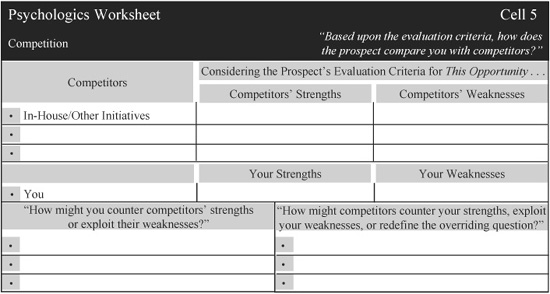

Included in Cell 5 of the Psychologics Worksheet (Figure 7.4) are counters to the competition, the selling points that allow you to differentiate yourself from the known or likely competition’s approaches or expertise. If you are a small engineering consulting firm bidding against a larger, more diverse competitor (for example, a broad-line management consulting firm), you might try to claim that your narrower focus and your size are strengths. That is, the project, you might argue, involves an IT problem requiring a rather narrow IT solution, especially by a consultancy whose relatively small client base allows for better, more client-oriented service. Of course, the larger firm would argue quite differently. Similarly, if you headed a team of in-house professionals proposing a particular study and if management was thinking of soliciting outside bids for the same study, you would probably need to argue that your team’s greater familiarity with your own organization and its situation was highly advantageous and beneficial.

In identifying your competition, you should always consider potential in-house competitors as well as the prospect’s other initiatives. The latter and your proposed initiative are always competing for the allocation of the prospect’s scarce resources. In generating counters to the competition, however, you must consider this as well: Counters to the competition need to relate to the evaluation criteria. Assume that yours is an international firm with 25 offices around the world and that the competitor is a “single-shingle” outfit—one consultant, perhaps a university professor, operating out of a home office. Your large firm with strategically placed offices offers you little or no competitive advantage unless your size and location are meaningful for the proposed project—that is, unless the evaluation criteria make them meaningful.

FIGURE 7.4 Psychologics Worksheet, Cell 5: Competition

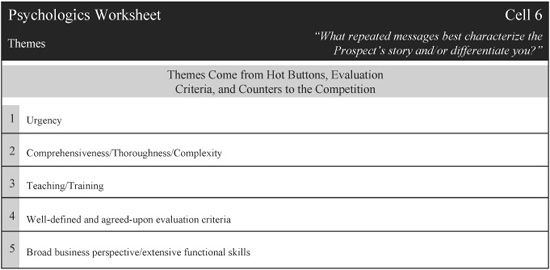

Selecting the Themes

Themes, as we’ve seen, come from three potential sources—hot buttons, evaluation criteria, and counters to the competition. If you have downloaded the complete Psychologics Worksheet, you will notice that arrows from each of these sources point to the Themes cell (Cell 6). However, not all hot buttons, evaluation criteria, and counters to the competition should become themes. Themes are your highlighted essential messages, and they can be highlighted, like the italicized word in this sentence, only if other things are not. Therefore, you want to use themes sparingly, choosing perhaps three to five in an average-length proposal. Given that your Psychologics Worksheet might have as many as 20 hot buttons, evaluation criteria, and counters to the competition, which three to five should become themes? These are my suggestions:

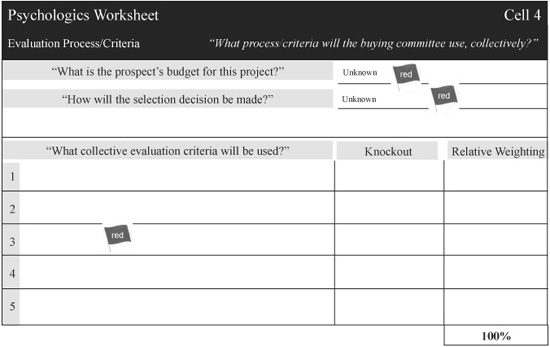

1. Concerning hot buttons, choose the desires and concerns of medium- and high-power-base buyers. As the Psychologics Worksheet, Cell 3 (see Figure 7.5) suggests, you should indicate each buyer’s power base and receptivity. Power base refers to a buyer’s relative influence in this buying opportunity, not to the buyer’s general level of influence within the organization. Receptivity refers to a buyer’s relative reception to your selling efforts to date, from “++” (a strong ally) to “– –” (an outright enemy). Note the lack of a neutral rating. Eventually, everyone will have to say “Yea” or “Nay.”

2. Concerning evaluation criteria, select those on which you believe you rate highly or that the buyers weight highly.

3. Concerning counters to the competition, choose those that provide an opportunity to significantly counter competitors’ arguments or moves, remembering that your competitors also can include in-house players or another of the potential client’s initiatives competing for the same resources.

Selecting your themes is a dynamic and creative process because the themes you end up with will not necessarily be phrased the same way or even be the same as one or more of the hot buttons, evaluation criteria, or counters to the competition. Some of your themes will be combinations or transmutations of these.

One likely combination exists in the ABC situation. “Service levels” is a hot button with obvious importance for Collins. Paul Morrison’s hot button, “well-defined and agreed-upon evaluation criteria,” is similarly important to him. To leverage both hot buttons, you could combine them. When you discuss Morrison’s desire for well-defined and agreed-upon evaluation criteria, you can use service levels as an example of the kind of criteria the study will employ.

The hazardous waste example discussed previously offers an example of a possible transmutation. “National consistency” and “flexibility” were two of the principles established to govern the program, and those two principles would seem incompatible and perhaps even contradictory. But a new theme could emerge from them—call it “balance.” That is, a salable quality of the proposers could be the ability to understand the national need for consistency but to remain flexible by balancing that need in light of the states’ and regions’ local circumstances. This theme of balance also leverages the third principle listed: “trade-offs.”

FIGURE 7.5 Psychologics Worksheet, Cell 3: Buyer receptivity

Developing the Themes

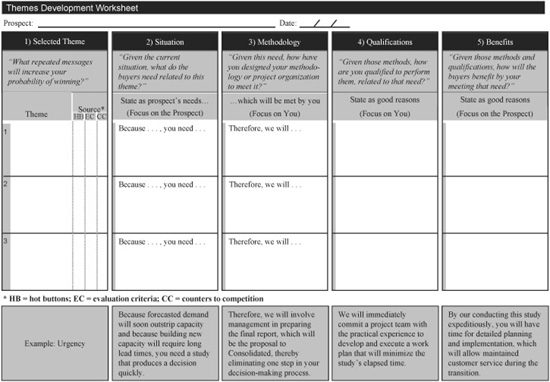

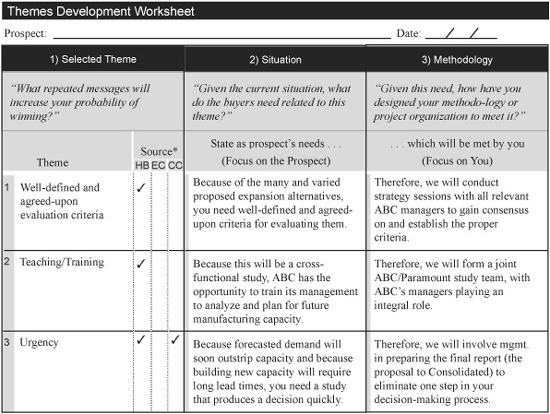

The downloadable Themes Development Worksheet is shown in Figure 7.6, although you won’t be able to see it very well in this book. That’s because it needs to be printed out in 11″ × 17″ or in A4. As several chapters in Part 3: Proposal Preparation illustrate, the worksheet allows you to develop much of the persuasive content you will employ both during the proposal process and in the proposal itself.

Using this worksheet, you can create a web of persuasion throughout your communication. The worksheet uses some of the generic-structure slots you’re already familiar with:

Given my organization’s SITUATION, these are the METHODS, out of a universe of possible methods, that you will use to solve our problem or realize our opportunity. Given those methods, these are your QUALIFICATIONS for conducting them. Given those methods and qualifications, these are the BENEFITS we will receive from your solving our problem or realizing our opportunity.

This logic can be applied to each of your proposal’s themes, and in a completely filled-out worksheet the argument gets developed both horizontally and vertically. From left to right, the worksheet spins a web of persuasion related to your theme. Assuming, for example, that your theme derives from a hot button, you will be demonstrating your responsiveness to that hot button in four different ways: first, that you understand its existence and my desire to address it; second, that your approach is designed to consider it; third, that you are qualified to act on it; and fourth, that I will benefit by your acting on it. The bottom of the Themes Development Worksheet contains an example of a theme, “urgency,” developed horizontally.

When the worksheet is expanded to contain several themes, an argument will begin to be developed vertically for several of the proposal’s major slots. For example, a completed worksheet would supply you with several good reasons for why you have designed your methodology as you have and for why you believe you are best qualified to conduct the project.

FIGURE 7.6 Themes Development Worksheet

In the following work session, you’ll see clearly how these techniques can be applied when you fill out a Themes Development Worksheet relevant to the opportunity at ABC. This worksheet is very important: It supplies a substantial amount of the persuasive content that will help you when you prepare your proposal. You also will be filling out Psychologics Worksheet cells related to hot buttons, evaluation criteria, and counters to the competition. I should note that you probably will find that filling out these cells is time-consuming. However, over time, as you gain experience, I guarantee that you will write the proposal itself much more quickly and persuasively. Additionally, on those occasions when others help you prepare your proposal, the worksheets provide an excellent method for communicating a consistent message to your team and, therefore, help you avoid the characteristics of so many of the proposals I’ve read that sound like they have been written by different people and then cobbled together.

CHAPTER 7 REVIEW

Identifying, Selecting, and Developing Themes

1. Identifying themes. Themes are the repeated expression of your abilities and capabilities to address hot buttons, meet evaluation criteria, and counter the competition:

![]() Hot buttons are needs and desires of individual buyers that can be addressed during your face-to-face meetings with me and other buyers, by altering your project’s methodology, and/or by altering your project staffing. Hot buttons almost always have emotional content.

Hot buttons are needs and desires of individual buyers that can be addressed during your face-to-face meetings with me and other buyers, by altering your project’s methodology, and/or by altering your project staffing. Hot buttons almost always have emotional content.

![]() Evaluation criteria are collective needs and desires of the buyers. They often are written, especially in an RFP. Evaluation criteria typically have technical content.

Evaluation criteria are collective needs and desires of the buyers. They often are written, especially in an RFP. Evaluation criteria typically have technical content.

![]() Counters to the competition are your strengths relative to the competition vis- à-vis the specific evaluation criteria for this proposal opportunity.

Counters to the competition are your strengths relative to the competition vis- à-vis the specific evaluation criteria for this proposal opportunity.

2. Selecting themes. Themes should be selected from:

![]() Hot buttons of medium- and high-power-base buyers whose receptivity you want to maintain or increase. Power base refers to a buyer’s relative influence in this buying opportunity, not to the buyer’s general level of influence within his or her firm. Receptivity refers to a buyer’s relative receptivity to your selling efforts to date.

Hot buttons of medium- and high-power-base buyers whose receptivity you want to maintain or increase. Power base refers to a buyer’s relative influence in this buying opportunity, not to the buyer’s general level of influence within his or her firm. Receptivity refers to a buyer’s relative receptivity to your selling efforts to date.

![]() Evaluation criteria on which you believe you rate highly or that the buyers weight highly

Evaluation criteria on which you believe you rate highly or that the buyers weight highly

![]() Counters to the competition that provide you with an opportunity to significantly counter competitors’ arguments or moves, remembering that your competition can also include in-house (do-it-themselves) options or other initiatives competing for the same resources

Counters to the competition that provide you with an opportunity to significantly counter competitors’ arguments or moves, remembering that your competition can also include in-house (do-it-themselves) options or other initiatives competing for the same resources

3. Developing themes. Themes spin a web of persuasion throughout the proposal. They can be developed by using the Themes Development Worksheet, which uses four proposal slots:

![]() SITUATION: Given the problem or opportunity, what is needed by the potential client, related to this theme?

SITUATION: Given the problem or opportunity, what is needed by the potential client, related to this theme?

![]() METHODS: Given that need, how will the project be configured, related to this theme?

METHODS: Given that need, how will the project be configured, related to this theme?

![]() QUALIFICATIONS: Given those methods, how are you qualified to perform them, related to this theme?

QUALIFICATIONS: Given those methods, how are you qualified to perform them, related to this theme?

![]() BENEFITS: Given those methods and qualifications, what benefits will accrue, related to this theme?

BENEFITS: Given those methods and qualifications, what benefits will accrue, related to this theme?

WORK SESSION 6:

Identifying Hot Buttons and Evaluation Criteria, Countering the Competition, and Developing the Themes for ABC

You understand that before you can develop your themes, you must identify the buyers’ hot buttons and evaluation criteria as well as determine how you will counter your competition.

Identifying Hot Buttons

You know that hot buttons involve the buying team members’ desires or concerns about the project and therefore have to be addressed by the way you and your team propose to conduct the project. You also know, because consultant Gilmore has told you and because you’ve seen it over and again in discussions with Gilmore and in his notes, that one of the hot buttons is thoroughness. Armstrong said the study needs to be “thorough and convincing.” Anil Gupta said the same. Morrison hinted at the same. Given these repetitions—hardly coincidental, you believe—it’s quite likely that Armstrong first sang the tune and that the others joined in the harmony.

That tune probably sounds good to the others, but for different reasons based on their buying roles and even their personalities. For Armstrong, thoroughness is a means by which he can achieve his goal of remaining competitive and persuading Consolidated to provide the capital funding. So thoroughness to him has an economic-buyer, bottom-line meaning. For Morrison, however, because he’s a technical buyer and because of his background and temperament, thoroughness may mean something quite different: perhaps the logical rigor required in a project of some complexity, a project whose alternatives are being advocated, he believes, without a comprehensive analytical basis. Those alternatives, according to Morrison, need to be examined thoroughly and convincingly, ideally by using his distribution model.

So as you develop your hot buttons, you try to remember that the roles individuals play on the selection committee influence their expectations and thus the hot buttons themselves and how they are construed. You also realize that detecting hot buttons is something of an art because you’re not necessarily dealing with hard data but with feelings, desires, perceptions, and hidden agendas. You have to try to get below the obvious and into the personalities, the “inside the buyers’ heads” issues, and the psychologics, because hot buttons almost always have emotional content.

For example, Armstrong said something to Morrison, who remarked about it—almost as an afterthought—to Gilmore. You missed it when the two of you discussed his meetings as well as the first two times you went through Gilmore’s notes, but this time it struck you as possibly important. Armstrong had encouraged Morrison and his project team to develop the in-house distribution model because he had been convinced that doing the project in house was both feasible and cost-effective. Armstrong also believed “that the project would provide a beneficial learning experience, so he gave his approval to proceed.”

Armstrong, it appears, not only desires professional development but actively supports it. And, it strikes you, he has a good many managers who need it. Collins, for example, appears to know little about the operations outside of marketing. She certainly knows little about manufacturing, a point she readily admitted to Gilmore. Most likely, manufacturing and marketing don’t talk very much to each other, even though what the one produces the other must sell and even though the selling itself and the customer service that goes along with it must rely on accurate production schedules, quality production, and the like. Frank Metzger, it appears, is in a similar position, knowing much about manufacturing but far less about marketing.

So if Armstrong is into teaching/training (that’s how you decide to phrase this potential hot button, although “professional development” and “staff development” are other options), maybe you can find a way to build teaching, training, and team building into your methodology.

You’re particularly sensitive to this hot button because of the recent experience of one of your colleagues. He had bid on but lost a proposal to a competitor. Following up, he called the company to try to determine why the project had been given to another firm. The winning firm, he was told, had included a significant training component in its methodology. In response, your colleague remarked that no one he interviewed had said anything about a training component. Every bidder, came the reply, was told the same thing. Perhaps every bidder was. Perhaps your colleague had missed a hot button that his competitor had detected and capitalized on. Perhaps the competitor was more adept at reading between the lines and getting below the surface.

As you turn to the hot buttons cell (Cell 2; see Figure 7.7), you try to keep four things in mind:

![]() First, hot buttons aren’t always explicitly stated. In searching for them, you should examine not only what was said but also what was left unsaid, or said between the lines, or said just below the surface. You’re looking for the psychological, the emotional, not just the logical.

First, hot buttons aren’t always explicitly stated. In searching for them, you should examine not only what was said but also what was left unsaid, or said between the lines, or said just below the surface. You’re looking for the psychological, the emotional, not just the logical.

![]() Second, hot buttons can be conditioned by the buyer’s role. For example, cost-related matters are likely to be hot buttons of an economic buyer or of a chief financial officer playing a technical buyer.

Second, hot buttons can be conditioned by the buyer’s role. For example, cost-related matters are likely to be hot buttons of an economic buyer or of a chief financial officer playing a technical buyer.

![]() Third, to make it easier to convert them into themes, you should try to designate hot buttons by key words or short phrases, such as thoroughness or complexity or involvement/respect.

Third, to make it easier to convert them into themes, you should try to designate hot buttons by key words or short phrases, such as thoroughness or complexity or involvement/respect.

![]() Fourth, for every hot button you detect, you should generate a benefit that will accrue from your addressing that hot button during the project. The likelihood of these benefits accruing often sways a buyer toward one competitor versus another.

Fourth, for every hot button you detect, you should generate a benefit that will accrue from your addressing that hot button during the project. The likelihood of these benefits accruing often sways a buyer toward one competitor versus another.

Your completed Cell 2 looks like Figure 7.7. The red flags indicate your current uncertainty about exactly how the hot buttons should be addressed. Those specific tactics you decide to bring up with Gilmore.

Identifying Evaluation Criteria

Here, you are troubled. As far as you can tell, Gilmore identified no evaluation criteria during his discussions with ABC. True, the technical buyers have hot buttons that they, singly, will use to evaluate the proposal. But no shared evaluation criteria exist—at least none that you know of. And Gilmore, as far as you know, didn’t ask about them. This fact has two ramifications. First, you cannot fill out Cell 4 for the evaluation criteria; second, because your counters to the competition (as well as your analysis of your and the competitors’ teams) need to be articulated in relation to those criteria, you must consider suspect everything you list on Cell 5 for the competition. Because you haven’t identified the evaluation criteria, you could be at a significant competitive disadvantage, especially since ABC has had good experience with one or more of your competitors.

FIGURE 7.7 The hot buttons, analyzed

It occurs to you that if a consultant-selection committee hasn’t identified evaluation criteria, a consultant has the opportunity to “help” the buyers identify those criteria. This is a win-win situation. The buyers win because they will have evaluation criteria that they can apply during their evaluation of the proposals. You win because you can influence the buyers so that the criteria are favorable to you—or at least not unfavorable.

Your completed (uncompleted, really) Cell 4 is shown in Figure 7.8. It contains a global red flag for the lack of evaluation criteria, as well as additional red flags for other information about which you haven’t a clue: ABC’s budget for this study and the process in which it will engage to select a consultant. Both these items, you believe, are crucial. ABC might very well have a budget for this study, and if you bid beyond it, you could trigger another economic buyer, probably at Consolidated, thereby introducing another buyer into the equation, of whom you would be completely unaware. That process could be one part of ABC’s decision-making efforts to select a consultant, another crucial element about which you’re uncertain. You know very well that a coach could help you with both of these key elements of the proposal-development process. You’re becoming increasingly aware that having a coach (or, ideally, coaches) is much more important than you had anticipated.

FIGURE 7.8 The evaluation criteria, analyzed

Analyzing the Competition

At the end of your initial meeting with ABC, Gilmore asked which other consulting firms were likely to bid on the project. Anil Gupta named three competitors. One is a firm similar to your own, with similar capabilities, against whom Paramount has competed numerous times. The other two are local companies specializing in facilities planning, plant layout, materials handling, and productivity improvement. In fact, ABC used one of those consultants several years earlier to help solve a materials-handling problem.

Your task is threefold: first, to understand these competitors’ strengths and weaknesses relative to those of Paramount; second, to determine Paramount’s strengths and weaknesses relative to the competition’s; and third, to determine how you can leverage your own strengths and exploit each competitor’s weaknesses. Of course, you also want to put yourself in your competitors’ shoes and think about how they might exploit your weaknesses. To help you complete this task, you turn to Cell 5 to analyze the competition (Figure 7.9), and following are some of your thoughts as you do so.

Gilmore knows the capabilities of your major competitor all too well. Paramount has competed against it with lackluster results. Once Paramount won, three times it lost, and, on one occasion, Paramount and the competitor both lost to a third firm. Because this competitor’s capabilities are every bit as diverse and strong as Paramount’s, you believe it’s important to have much more intelligence about it. On the project Paramount won, for example, did the client make available this competitor’s proposal? If so, what did the proposal contain, and what can you learn from it? On the studies Paramount lost, was Gilmore able to find out not only why Paramount lost but also why this competitor won? In all these situations, did the proposal-evaluation committees use evaluation sheets or circulate memos or otherwise keep records of their deliberations, and if so, did Gilmore request access to those documents? If he did not get insight at the time, can he get it now? Have there been other instances when your firm (but not Gilmore specifically) bid against this competitor on similar kinds of studies, and if so, what lessons were learned?

At this point, you wonder if your firm even has a “lessons learned” process, an established procedure for answering questions such as the preceding and a database containing the answers. You decide to discuss this issue with Gilmore.

FIGURE 7.9 The competition, analyzed

This competitor’s weaknesses? Perhaps because of its success rate against Paramount and because of its excellent reputation, your competitor may be somewhat complacent in addressing ABC’s needs. Or perhaps the ABC project may not be important enough for it to mount a major proposal effort. But all this, you realize, is pure speculation, and dangerous speculation at that. You’re wooing yourself into complacency (and making yourself feel less anxious) by surmising that this fierce competitor, this firm that has beaten Paramount all too often, will suddenly become complacent (and just at the right time, too—when you are preparing this proposal). Nevertheless, you record these supposed weaknesses in the designated place on Cell 5, making a mental note that you’re not very satisfied with your analysis.

You have just as much difficulty assessing the two local competitors, but for different reasons: You’re not familiar with them, and you haven’t found any details listed in your research on consulting firms. However, you suspect that they have strong capabilities in specific functional areas to be addressed during the proposed study. And you know, of course, that one of those companies has a major strength: It has already worked successfully with ABC. An equally important strength will be their cost. Since their proposed fees could be tens of thousands of dollars less than yours, how will you be able to communicate value for your higher-cost service? Since they aren’t full-service firms, these competitors have definite weaknesses, you believe, because they don’t have expertise in all the functional areas to be addressed during the project, including (among others) customer service and supply chain analysis, nor do they have sufficient experience and knowledge to properly evaluate the critical qualitative factors. In addition, their staffs may be too small to enable them to initiate and complete the study quickly, which is a major concern (a hot button, you hope) to key ABC management.

Your proposal strategy will have to stress the comprehensive nature of the project, which will demand a wide range of business skills that probably are beyond the more functional capabilities of these two firms. But you also must stress your considerable strength in the specialized skills of these smaller firms while convincing ABC that it needs more than such skills. You can counter the one firm’s successful experience with ABC by stressing Paramount’s successful completion of similar studies for comparable companies. Above all, you will have to stress the added value provided by your full-service firm and perhaps the risks to ABC of choosing a consulting firm whose more narrow focus could result in a study that is less comprehensive and thorough.

In these situations, there are always two other potential competitors: in-house competition and other initiatives competing for the same resources that would have to be used for your project.

![]() Concerning in-house competition: Morrison admitted to Gilmore that he had volunteered to do the study in-house. For all you know, Morrison may be working behind the scenes even now to sell this approach. Or, during the selection process, he could take one or another of the consultant’s methodologies and try to convince Armstrong that Morrison’s team could use it. You consider these possibilities unlikely, however. Besides, you undoubtedly will have good themes to counter this in-house competition. Because you decide that in-house competition is unlikely, you don’t complete that portion on Cell 5.

Concerning in-house competition: Morrison admitted to Gilmore that he had volunteered to do the study in-house. For all you know, Morrison may be working behind the scenes even now to sell this approach. Or, during the selection process, he could take one or another of the consultant’s methodologies and try to convince Armstrong that Morrison’s team could use it. You consider these possibilities unlikely, however. Besides, you undoubtedly will have good themes to counter this in-house competition. Because you decide that in-house competition is unlikely, you don’t complete that portion on Cell 5.

![]() Concerning other initiatives: It would be helpful if you knew ABC’s strategic direction, but you note a red flag next to that item on Cell 1 of your Logics Worksheet. By understanding ABC’s strategic direction, you could anchor your proposal’s argument by clearly linking the proposed initiative with that direction. Nevertheless, you are confident that this initiative is absolutely vital not only for ABC’s health but also for its survival. You decide, therefore, not to include that analysis in Cell 5, which, in modified form, looks like the one shown in Figure 7.9.

Concerning other initiatives: It would be helpful if you knew ABC’s strategic direction, but you note a red flag next to that item on Cell 1 of your Logics Worksheet. By understanding ABC’s strategic direction, you could anchor your proposal’s argument by clearly linking the proposed initiative with that direction. Nevertheless, you are confident that this initiative is absolutely vital not only for ABC’s health but also for its survival. You decide, therefore, not to include that analysis in Cell 5, which, in modified form, looks like the one shown in Figure 7.9.

Selecting and Developing the Themes

In selecting your themes, you pay close attention to the analysis of power base and receptivity in Cell 3 (Figure 7.10).

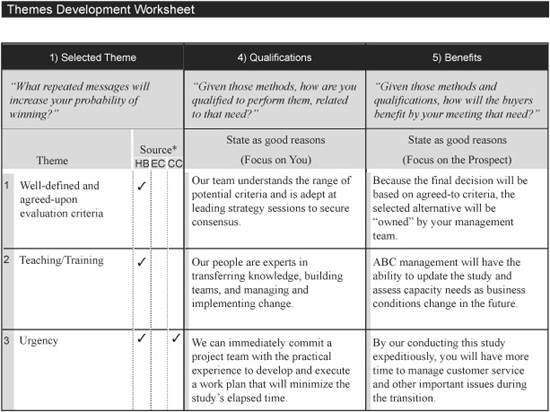

This information helps you determine which hot buttons you want to emphasize. For example, although Metzger has a hot button (“Consideration of his preferred option),” Metzger is a low-power-base buyer, and your time will be better spent trying to persuade the more influential buyers. Metzger, moreover, also has a “–” receptivity rating, probably preferring one of the competitors (and likely a coach for it). Little you do will persuade him to support you. The themes you select, which are displayed in Figure 7.11, will be developed on your Themes Development Worksheet (Figure 7.12a and 7.12b), which will supply your proposal and presentation with the majority of its persuasion. The entire Themes Development Worksheet can be downloaded from http://mhprofessional.com/freed.

FIGURE 7.10 Power base and receptivity, analyzed

FIGURE 7.11 The identified themes

FIGURE 7.12a The Themes Development Worksheet’s developed themes (columns 1–3)

FIGURE 7.12b The Themes Development Worksheet’s developed themes (columns 1, 4, and 5)

In the first column of each row, you record a theme; for example:

Well-defined and agreed-upon evaluation criteria

In the second column (Situation; Figure 7.12a), you state ABC’s needs related to that theme, follow the worksheet’s prompts, and therefore use the sentence structure “Because . . . you need. . . .” In this column, the focus (and therefore the subject of the sentence) is the prospect, what the prospect needs given the current situation:

Because of the many and varied proposed expansion alternatives, you need well-defined and agreed-upon criteria for evaluating them.

In the third column (Methodology; Figure 7.12a), you explain how your study will address that need. In this column, the focus is on you, on what you will do to move the prospect away from the current situation and toward the desired result:

Therefore, we will conduct strategy sessions with all relevant ABC managers to gain consensus on and establish the proper criteria.

In the fourth column (Qualifications; Figure 7.12b), you explain your qualifications for addressing the need. In this column, the focus is again on you, on how you are qualified to do what you claim you will do:

Our team understands the range of potential criteria and is adept at leading strategy sessions to secure consensus.

In the last column (Benefits; Figure 7.12b), you state the benefits of meeting the need. In this column, the focus returns to the prospect, on the benefits the prospect will receive related to this theme:

Because the final decision will be based on agreed-to criteria, the selected alternative will be “owned” by your management team.

As you complete subsequent rows for your additional themes, you try to stay alert to the interrelationships among the themes, the lines of force that connect them. For example, you consider two selected themes that aren’t yet developed in Figure 7.12a and Figure 7.12b: Your broad business perspective is a counter to some of the competitors and will help ensure the study’s comprehensiveness, a hot button. So in writing or rewriting the row for one theme, you try to include language that intersects with another.

With the Themes Development Worksheet completed, you now have your web of persuasion, spun out among the proposal’s various slots: SITUATION, METHODS, QUALIFICATIONS, and BENEFITS. In subsequent work sessions, you will place that persuasion strategically throughout your written proposal and throughout your discussions with ABC as well as in your proposal presentation. For example, the Situation and Methods columns will provide you the persuasion necessary to answer this question: “Why, out of a universe of possible approaches, have you chosen this one, for this situation?” That question’s answer (though the buyers might not consciously recognize why the answer is so powerful) is this: “We have designed our approach as we have because it addresses your hot buttons, meets your evaluation criteria, and counters our competition.” Done right, that kind of rationale for your methods section is extraordinarily persuasive.