CHAPTER 10

Writing the Methods Slot

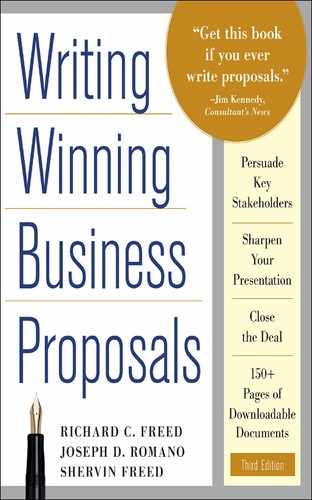

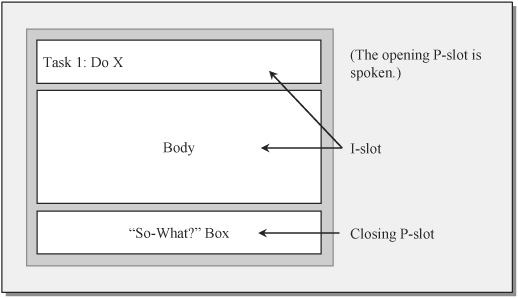

In Chapter 5, you saw that your methodology includes two kinds of tasks: actions necessary for achieving the project’s objective and activities important for planning and communicating. (See Figure 10.1.) Note that both kinds of tasks tell me how you will do things—how you will achieve the project’s objectives and how you will plan and communicate with me while doing so.

If you have worked for me before and I trust you explicitly, or if you have discussed your methodology with me and I am satisfied by how you will achieve your objective, or if your leadership style isn’t detail oriented, then explaining how might be all that you need to do. In many situations, however, how isn’t nearly enough, as the following example (based partly on the ABC case in Appendix A) ought to illustrate.

Assume the following:

![]() You are Marcia Collins, and I (switching roles here) am the consultant.

You are Marcia Collins, and I (switching roles here) am the consultant.

![]() As ABC’s vice president of marketing, you are confident about your market forecast that predicts an imminent shortfall of capacity.

As ABC’s vice president of marketing, you are confident about your market forecast that predicts an imminent shortfall of capacity.

![]() Because I know that the engagement’s success will depend upon a validated forecast, I need to explain to you how I will validate that forecast.

Because I know that the engagement’s success will depend upon a validated forecast, I need to explain to you how I will validate that forecast.

![]() You, of course, believe that such validation would be a waste of time and money.

You, of course, believe that such validation would be a waste of time and money.

![]() I am presenting my proposal to you and your management team.

I am presenting my proposal to you and your management team.

![]() Just before displaying the first slide of the methods section, I say: “Our first task will be to validate ABC’s market forecast.”

Just before displaying the first slide of the methods section, I say: “Our first task will be to validate ABC’s market forecast.”

FIGURE 10.1 Your methodology includes both actions and activities.

Now, remember, you are Marcia Collins. How do you feel, Marcia? Angry? Embarrassed? Astonished, threatened, hostile, bitter, disbelieving, undermined? If your receptivity rating was a “single plus,” it’s now likely a “single minus” (or worse). If it was a “single minus,” it’s now a “double minus.” I made a huge mistake by not having discussed with you, before the presentation, this key task in our methodology. I also failed to use a simple and yet extraordinarily powerful concept that will help you to develop persuasive methods sections. The concept is called PIP, which stands for Persuasion–Information–Persuasion, and the rest of this chapter explains what it is and how to use it.

What Is PIP?

Persuasion primarily involves logical or emotional appeals intended to change beliefs or produce conviction. Information primarily involves facts. The power of the PIP technique rests on these commonsense assumptions:

![]() Proposals contain both information and persuasion.

Proposals contain both information and persuasion.

![]() Proposals (and their sections and subsections) have beginning, middle, and ending slots.

Proposals (and their sections and subsections) have beginning, middle, and ending slots.

![]() When presented with a three-part sequence (i.e., a beginning, middle, and end), people tend to remember the beginning and ending items much more than those in the middle.

When presented with a three-part sequence (i.e., a beginning, middle, and end), people tend to remember the beginning and ending items much more than those in the middle.

![]() If you need to be persuasive, as opposed to just informative, your persuasion should go in the first and last slots.

If you need to be persuasive, as opposed to just informative, your persuasion should go in the first and last slots.

To sense the importance of the first and last slots, consider a sequence of three proposal presentations. If you were one of three bidders, you’d want to arrange to be first or last. As first presenter, you’d have the opportunity to set the tone and create the standard by which later presenters would be judged. As last presenter, you’d have the opportunity to make the last (and, you’d hope, a lasting) impression. The middle presenter risks getting lost in the shuffle, especially in a very close competition.

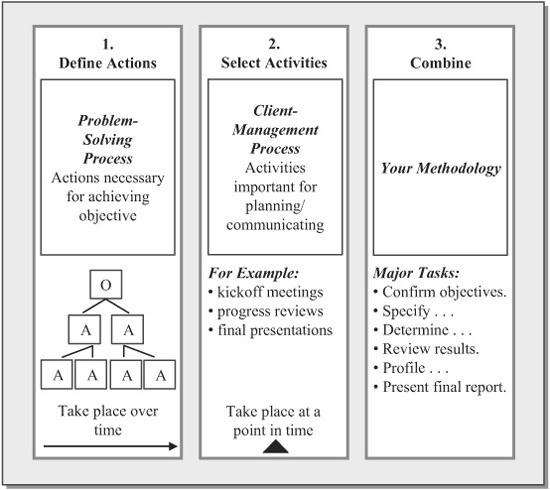

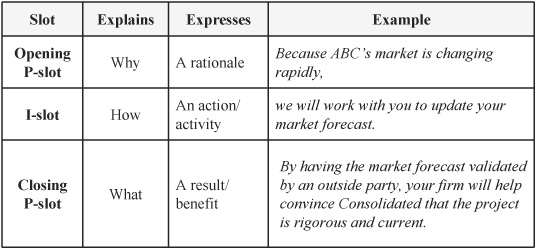

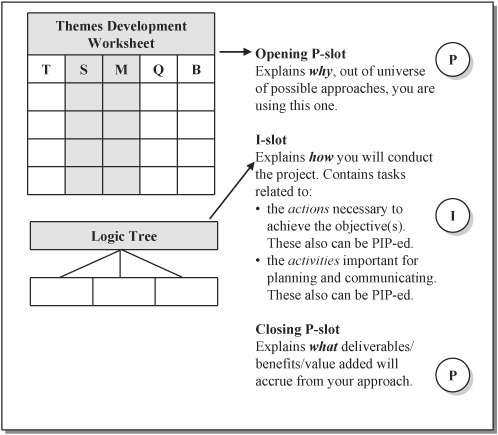

I call the beginning and ending slots, where you place your proposal’s persuasive content, persuasion slots (P-slots). The opening P-slot explains why something should be done, and the closing P-slot explains what will result (for example, what benefit will accrue) from the doing. Persuasion slots always frame or “sandwich” an information slot, an I-slot, which explains how something will be done.

Now let’s see how PIP works, or should have worked, in my presentation to Collins and her team. So far, I had filled the information slot, the I-slot, explaining how, in part, I would achieve the project’s objective (Figure 10.2).

Now assume that I had provided a rationale for what I was going to do, explaining why the how should be done. Figure 10.3 shows that rationale along with an improved I-slot.

How do you feel now, Marcia? Of course, you’re still angry and embarrassed, because I have still made the crucial mistake of not having discussed this issue with you before the presentation. But notice how you are less angry, less embarrassed. Why? Because I’ve explained why. I gave you a good reason for why I’d do what I said I’d do. I filled the opening P-slot by providing a rationale.

FIGURE 10.2 The I-slot and what it does

FIGURE 10.3 The opening P-slot and what it does

FIGURE 10.4 The closing P-slot and what it does

If I need to be even more persuasive, I can fill the closing P-slot by explaining what benefits will accrue from the doing, as shown in Figure 10.4.

PIP: Persuasion–Information–Persuasion. Three slots. The first and last are relatively more important and, therefore, include the persuasion. The middle slot is relatively less important and contains the information. That information is almost always necessary, because it states the tasks necessary for achieving your objective. But the information isn’t always sufficient. By itself, it might not be as persuasive as it needs to be.

Now that you understand how PIP works, we can talk about how you can use this organizational technique at various levels of the methods section (as well as throughout the entire proposal).

PIP at the Task Level

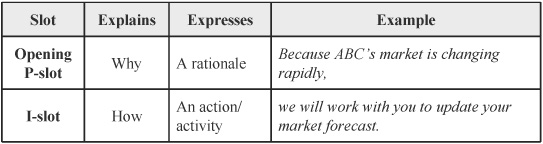

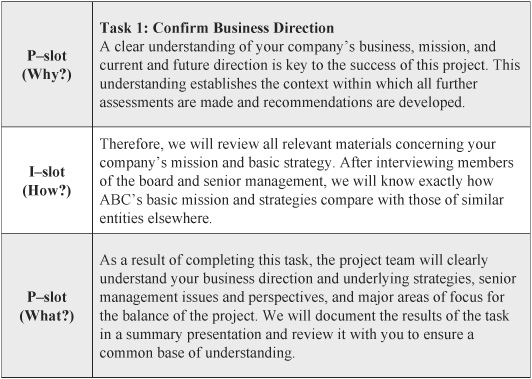

If necessary or appropriate, each task in your methods section can be organized according to PIP, as suggested by Figure 10.5.

FIGURE 10.5 P-slot questions at the task level

The informational part (the middle I-slot, shown as a circle in Figure 10.5) is the action or activity itself. It explains how the task will be performed. If you sense that I want to know why you are performing a task, you might decide to provide some good reason, in the form of a rationale, for its performance; therefore, you’d fill the opening P-slot by providing that rationale. If you have a good rationale for conducting the task, it’s because the task will produce some definable end product, or benefit, some understanding or knowledge or validation framework or decision point. If that end product is worth mentioning, you can fill the closing P-slot by explaining what the task will accomplish or what benefits or value will accrue from its accomplishment.

Imagine the difference in persuasion between a series of tasks that are PIP-ed,1 like that one in Figure 10.6, and a series that omits all the P-slots. The latter would contain only information related to how each of the tasks would be performed. The PIP-ed series would also explain to me why you are doing what you propose to do and what benefit or value I would receive from your doing it.

Figure 10.6 obviously shows a PIP-ed task in a text proposal. In a slide presentation, you can use PIP as shown in Figure 10.7. The opening P-slot, the task’s rationale, is usually spoken, often as an oral transition before you reveal the slide. The I-slot, where you explain how the task in the headline will be achieved, is shown in the body of the slide. The closing P-slot can be revealed as a build in what is sometimes called a “So What?” box at the bottom of the slide.

FIGURE 10.6 PIP at the task level

FIGURE 10.7 Using PIP in a presentation slide

Why aren’t the tasks PIP-ed in many if not most of your proposals? I can think of three reasons:

1. The tasks just don’t have to be PIP-ed. That is, during the business-development process, you have already persuaded me that your methodology is sound; as a result, you don’t have to provide me with a rationale for why you are proposing the tasks or with a discussion of the benefits of your completing the tasks.

2. You don’t fill the opening and closing P-slots because you fail to consider my needs. Although you know why you are completing the tasks as well as the benefits of your doing so, possibly because you have done similar projects dozens of times, I don’t know what you know.

3. You don’t know about or understand the strategic benefits of using PIP.

Now you know.

PIP at the Methods Section Level

Your methods section is more than a collection of tasks. It has a beginning, middle, and end; an introduction, body, and conclusion. Let’s focus on the introduction, on the introductions in proposals you’ve written and read. If your experience is like mine, those introductions begin something like this:

We recommend the following six- [or five- or ten-] step approach.

Ask yourself: Is that information or persuasion? Of course it’s the former. It doesn’t provide a rationale for why you have constructed your methodology as you have. It doesn’t answer the question, “Why out of a universe of possible methodologies have you chosen this one?” It doesn’t, that is, fill the opening P-slot at the methods-section level.

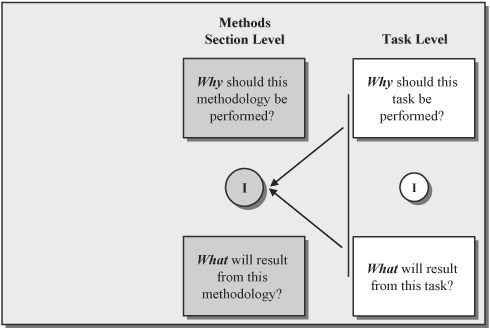

As Figure 10.8 illustrates, all your tasks (all of which could themselves be PIP-ed) form the middle or the body of the methods section. At the methods-section level, those tasks are the I-slot, explaining how you will achieve the project’s objective. As is always the case, above and below the I-slot are P-slots, which you must decide whether to fill. The entire methods section can be organized according to PIP.

When you write the introduction to your methods section, ask yourself if you have filled the opening P-slot. For example, does your introduction “recommend a three-phase approach” and pretty much leave me with only that information? Or should it go on to explain persuasively that such an approach will be employed because the phases will, for example:

![]() Allow me to achieve short-term results to make subsequent phases “pay as you go.”

Allow me to achieve short-term results to make subsequent phases “pay as you go.”

![]() Allow me to address broader strategic issues early on before focusing on more tactical questions.

Allow me to address broader strategic issues early on before focusing on more tactical questions.

FIGURE 10.8 P-slot questions at the methods-section level

![]() Continuously build on each other so that decisions reached in earlier phases influence and help screen options in later ones, thus leading to economies because I can choose to limit further evaluation in later phases based on analyses performed in earlier ones.

Continuously build on each other so that decisions reached in earlier phases influence and help screen options in later ones, thus leading to economies because I can choose to limit further evaluation in later phases based on analyses performed in earlier ones.

Does your introduction recommend collaboration between your team and mine and pretty much leave me with that information only? Or should it go on to explain that the study is strategically planned to meet my specific needs by employing a team approach that will, for example:

![]() Generate enthusiasm and commitment for the project’s potential outcomes.

Generate enthusiasm and commitment for the project’s potential outcomes.

![]() Keep me informed at every major step of the project.

Keep me informed at every major step of the project.

![]() Result in jointly developed and better accepted recommendations and action plans.

Result in jointly developed and better accepted recommendations and action plans.

![]() Efficiently resolve newly surfaced issues.

Efficiently resolve newly surfaced issues.

![]() Keep the lines of communication open.

Keep the lines of communication open.

![]() Efficiently transfer to your team my organization’s intimate knowledge of your firm.

Efficiently transfer to your team my organization’s intimate knowledge of your firm.

![]() Most efficiently transfer to my people your team’s knowledge, technology, and/or skills.

Most efficiently transfer to my people your team’s knowledge, technology, and/or skills.

Your introduction to METHODS provides a great opportunity to sell your methodology, to explain persuasively to me and others on the consultant-selection committee exactly how your methodology contains elements that will lead us to a more successful and beneficial project.

If you have completed a Themes Development Worksheet (TDW) (see Figure 10.9), you already will have generated much of the persuasive content for the opening P-slot of METHODS.

The Situation (S) and Methods (M) columns of your Themes Development Worksheet provide the opening P-slot material, the rationale for constructing your approach as you have. Because those columns’ content contains your themes, your opening P-slot implicitly (and often without my realizing it) communicates the following:

We have designed our methodology as we have because it addresses your hot buttons, meets your evaluation criteria, and counters our competition.

FIGURE 10.9 Your TDW provides the content for the methods section’s opening P-slot.

If you have done a good job on your Themes Development Worksheet, your opening P-slot to METHODS can’t not be persuasive! If you have four themes, you will have four reasons arguing that out of a universe of possible approaches, yours is the best for our situation. The work session at the end of this chapter, which is essential reading, will clearly demonstrate how the TDW’s Situation and Methods columns provide most if not all the content for your methods section’s introduction.

As Figure 10.8 and Figure 10.9 illustrate, the conclusion to your methods section also contains a P-slot. Rather than ending with a discussion of the tenth task of the third phase—i.e., ending with information—you can persuasively conclude your methods section by itemizing the expected deliverables (if they haven’t been identified within the tasks), by summarizing the most important deliverables (if they have been included in the tasks), and/or by explaining to me the value that your approach will add, the benefits that will accrue, during the project.

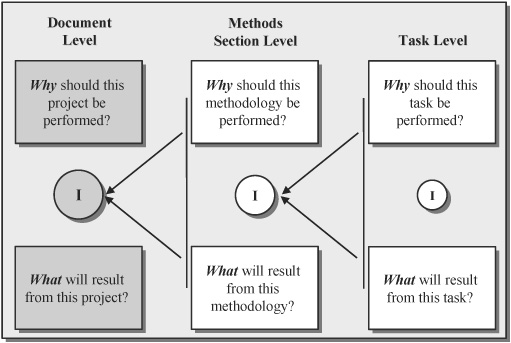

PIP at the Document Level

I doubt that you have ever seen a proposal whose methods section either began or ended the document. Typically, methods sections reside in the middle of the proposal. At the document level, the methods section functions as the document’s I-slot. As Figure 10.10 reveals, the document level also contains two P-slots:

FIGURE 10.10 P-slot questions at the document level

![]() At the document level, the opening P-slot provides a persuasive rationale for why the project itself should be done. That P-slot is SITUATION, which (as Chapter 9 explained) is usually formed into a background section that argues the need for the entire project.

At the document level, the opening P-slot provides a persuasive rationale for why the project itself should be done. That P-slot is SITUATION, which (as Chapter 9 explained) is usually formed into a background section that argues the need for the entire project.

![]() At the document level, the closing P-slot discusses the benefits that will accrue from the project. That P-slot is BENEFITS, which we will discuss in Chapter 12.

At the document level, the closing P-slot discusses the benefits that will accrue from the project. That P-slot is BENEFITS, which we will discuss in Chapter 12.

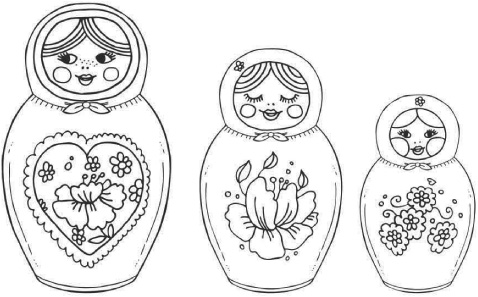

PIP and Proposal Strategy: Determining the Needed Level of Persuasion

Think of the various levels of PIP as a set of Russian nesting dolls (Figure 10.11). Your document is the largest doll, whose opening P-slot can be SITUATION and whose closing P-slot can be BENEFITS. The next smallest is all the tasks in your methodology, which itself can be PIP-ed. The smallest is all of your methodology’s tasks, which themselves can be PIP-ed. When you use the PIP strategy, you are explaining to me, at every level of the proposal, from one handcrafted doll to another, why something must be done, how it should be done, and what I will receive from your doing it.

When I say that something can be PIP-ed, you might be asking an important question: When should a P-slot be filled? In this last section of the chapter, we need to discuss that strategic question.

FIGURE 10.11 The various levels of P-slots are like Russian nesting dolls.

Because P-slots exist at the beginning and ending of things, they’re easy to find. Once you find them, however, you have to decide whether they should be filled. Your decision will depend on your sense of the situation, which will be different in every proposal opportunity. As a friend recalls a proposal situation some years ago when he was a fairly inexperienced consultant:

I wrote a proposal that I thought was going to be exactly like another proposal a consultant wrote for another company. Both companies competed in the same industry and manufactured the same products in almost the exact same geographic area. I pulled out that other proposal in order to boilerplate from it. I thought this would be a cakewalk. But by the time I was done, the only thing the other proposal did was to supply some neat ideas for me.

The consultant’s earlier proposal was written to a company for which he had done ten previous projects. He knew the president very well (the president’s son was also a client), and the company was extraordinarily successful. But the current proposal was for a company where I had never met anybody; the company was in trouble; there was no warm feeling; there was no ten years of experience; there were no previous assignments.

The earlier proposal, according to the consultant, was sort of a “Hey, Stan, this kind of confirms what we will do together, and we will do our best, and if we blow it we will change in midstream, and it has been great seeing you.” But the current proposal is, “number one you don’t know me, number two I have to establish my credentials and my firm’s credentials, number three we are sorry we took so long to respond, because we lost your letter (which is really number four); of all the firms you talked to, however, we are the only one with the exact right qualifications—here they are,” and now, suddenly, we have a totally different proposal.2

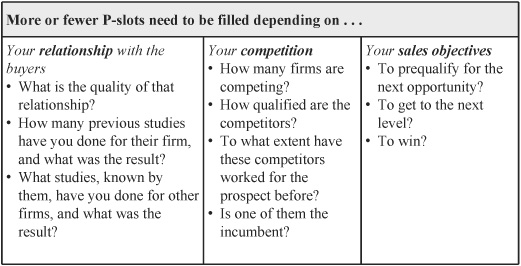

Obviously, the second proposal had to be much more substantial and persuasive than the first; therefore, more of the P-slots had to be filled. But how do you decide just how persuasive your proposal needs to be? I can think of at least three factors you should consider: your relationship with the buyers, the competition, and your sales objective, as shown in Figure 10.12.

The first two categories, “relationship with buyers” and “competition,” are fairly obvious. Assume, for example, that the quality of your relationship with me is excellent, that you’ve done many studies for me and my organization, and that I’m not talking to any of your competitors. No one else is competing for my attention, and, in the past, when you have worked for me, you’ve done so very successfully. Your credibility is a given; you don’t have to acquire it. I’ve asked you to meet with me to discuss a problem that needs to be solved, and you have convinced me in our two-hour meeting that you understand the problem and have the right people and approach for solving it. We’ve also discussed costs, and I’ve agreed to them.

FIGURE 10.12 Considerations to determine if and how much the P-slots should be filled

In short, you’ve sold the job, and I’ve asked you for nothing more than a confirmation letter. As a result, you need to do very little with the P-slots. On the task level, there might be little need to provide a rationale for each task and to indicate the benefits of completing it. In fact, you might need to do nothing more with the tasks than include them in a Gantt chart. On the methods-section level, there might be little need to discuss the rationale for your specific approach. At the document level, you might not even need to provide a rationale for why the study should be done nor argue the benefits that will accrue from its doing.

Conversely, if five firms are competing and some of them have capabilities equal to yours, and if they, not you, have worked successfully with me, your proposal will have to be very persuasive indeed. Many of the P-slots will have to be filled—and filled well. At each crucial point, you may have to explain why a task is important to perform—and the results of its performance; why you have designed your approach precisely as you have—and the value of your conducting it; and why, from your point of view, the study should be performed—and the benefits to be gained from your performing it.

In this second case, however, you should seriously consider not writing a proposal at all, especially if my issue doesn’t play to your strengths or if I am not one of your target clients or am not in one of your target industries. Instead, redeploy your resources for some other battle you have a better chance to win.

The third category in Figure 10.12, “sales objectives,” is important because too many proposal writers view the written proposal as having only one sales objective: to close the deal. A good example of this proposal-as-last-effort viewpoint is the requirement at some consulting firms (sometimes by fiat, sometimes by institutional practice) that letter proposals contain signature blocks at the end of the document, prefaced by a sentence such as “If you agree with the terms as set forth in this proposal, please sign in the appropriate space and forward one copy to. . . .” Required even in competitive situations, this procedure views the proposal as a final product rather than as a negotiating tool—one more possible stage in the proposal process to help you get closer to what then could be your best and final offer to me.

In many situations, of course, the proposal is your best and final offer because I won’t allow you any other. But in other situations, the proposal-as-final-offer strategy can be most unstrategic, because your document’s sales objective is not always to win but to get you one step closer to what can become a “done deal.”

That is, sometimes your immediate sales objective is to get to the next stage, the better to sell at the next level or the better to continue to try to sell at the same level. For example, assume that you don’t have access to the economic buyer. In that situation, the strategy could be to write a document whose sales objective is not to close the deal but to get buy-in from the technical and user buyers, who then, in effect, become part of your team. At that point, they can coach you to meet the new sales objective, which would be to work together to sell to the economic buyer. The new document or presentation could then be specifically tailored to meet the new sales objective.

Even if you have access to all the buyers, you can profitably choose to view the written proposal or oral presentation as a discussion document. Indeed, many experienced consultants try not to include fees in the written proposal. They label it a “discussion document” so that they can meet with me and my team to hammer out the methodology and our level of involvement; agree on the deliverables; and, of course, establish the trust and chemistry necessary for us to say “yes” with confidence. If by the end of that meeting, they haven’t yet sold the work, they’re at least closer, and they know even more about me, my team, and my organization’s problem or opportunity. Their proposal and our relationship will be better because of it.

On some (certainly less frequent) occasions, the objective isn’t to sell on any level at all but simply to get into the game so that you can play the next time around. A friend of mine, an environmental consultant, decided to play on these terms. He did not originally receive a request for proposal (RFP) from a Canadian governmental agency because the agency wasn’t aware that his firm did environmental consulting. After finding out about the opportunity through the Internet, however, he asked for and received permission to bid, and did so, even though a dozen other competitors were involved and the job probably was wired to begin with. His sales objective was not to win but to prequalify for future work. His document functioned less like a proposal and more like a response to an RFQ (request for qualifications).

In the work session of this chapter, you’ll get a good sense for the level of persuasiveness needed and, therefore, how many of the P-slots need to be filled. You’ll begin to see how the Russian dolls fit together, the better to view your handiwork and craftsmanship.

CHAPTER 10 REVIEW

Writing the Methods Slot

1. The methods slot consists of your methodology (as discussed in Chapter 5) plus your good reasons for performing it.

2. These good reasons take two forms: first, a rationale for why you will do what you say you will; second, the results or benefits that will accrue from your doing it.

3. The good reasons can go into persuasion slots (P-slots) that precede and follow information slots (I-slots).

4. The opening P-slot explains why you will do something. The I-slot explains how you will do it. The closing P-slot explains what will result from your doing it. Hence, PIP.

5. PIP can be used to organize the methods section at the task and section levels.

6. How many P-slots should be filled depends on your relationship to the buyers, the competitiveness of the situation, and your sales objective for the document or presentation.

WORK SESSION 8:

Writing the Methods Section for ABC

In your estimation, the individuals on the ABC buying team are a rather diverse lot with solid but rather narrow functional capabilities. In evaluating your proposal, some will look for a technically precise methodology that also addresses their individual, varied concerns and needs, that is, one that responds to their different perceptions of ABC’s current situation as well as their sometimes similar but often different hot buttons. Your Themes Development Worksheet addresses these hot buttons as well as some of the competition’s exploitable weaknesses.

Composing the Opening P-Slot for the Methods Section

In fact, the Situation and Methodology columns of that worksheet provide (as they always do) most of the persuasive material for the opening P-slot to the section. You use those claims and follow them with a statement that forecasts the five major tasks. Your draft of the opening P-slot to the methods section looks like this:

We have designed our methodology for three important reasons. First, because forecasted demand will soon outstrip capacity and because building new capacity will require long lead times, you need a study that leads to a decision quickly. Therefore, we will involve ABC’s management to expedite the retrieval, development, and analysis of relevant information, thus reducing the time for analysis. We will also work with your management team to prepare the final report. This document will be not only a recommended expansion plan but also an actual proposal to Consolidated that justifies the cost of the expansion by articulating the compelling reasons to move forward with urgency.

Second, because of the many and varied proposed expansion alternatives, you need well-defined and agreed-upon criteria for evaluating them. Therefore, we will conduct strategy sessions with all relevant ABC managers to gain consensus on and establish the proper quantitative and qualitative criteria. Quantitative criteria worth considering include ROI, investment incentives, taxes, and costs related to labor, service levels, distribution, construction, and utilities. Qualitative criteria could include labor supply, union climate, workforce characteristics, productivity, environmental regulations, vocational training capabilities, manufacturing support services, risk, controllability, the ability to develop and promote employees, and the flexibility to react to unanticipated changes.

Finally, because this will be a cross-functional study, ABC needs a senior, multi-faceted consulting team with a broad range of business capabilities, including marketing, manufacturing strategy, facilities planning, logistics, financial analysis, and human resources. These capabilities are necessary to ensure that all relevant options are surfaced and evaluated in a practical manner, that the most desirable options and their attributes are clearly identified and defined, and that ABC’s management not only has the ability to make the right decision but that Consolidated is convinced of its appropriateness. Therefore, we will form a joint ABC/Paramount study team with ABC’s managers playing an integral role, thereby providing the additional benefit of training ABC’s management to analyze and plan for additional capacity in the future.

Specifically, our methodology consists of the following five major tasks:

[note to myself: insert Gantt chart here]

Please note that the five-month estimate for completing the study is conservative. Working with your management team, we will make every effort to accelerate the completion of the tasks discussed in greater detail in Appendix A.

After composing this P-slot, you turn your attention to the five major tasks that you developed by using a logic tree. Your purpose is to build persuasiveness into the methodology by providing beginning and ending P-slots for each of these major tasks.

Composing the P-Slots for Task 1: Confirm ABC’s Long-Term Product Forecast

The opening P-slot for this task will be particularly important. Without providing a highly persuasive rationale for confirming the forecast, you run the considerable risk of alienating Collins, who not only developed the forecast but also has confidence in its accuracy. You decide to use two key arguments:

![]() An accurate forecast is critical for determining the magnitude and timing of additional manufacturing resources (that is, it drives the entire analysis).

An accurate forecast is critical for determining the magnitude and timing of additional manufacturing resources (that is, it drives the entire analysis).

![]() An independent confirmation of the forecast will assure Consolidated that ABC’s projected growth and timing are real and merit significant capital investment.

An independent confirmation of the forecast will assure Consolidated that ABC’s projected growth and timing are real and merit significant capital investment.

Your closing P-slot for this task, where you have the opportunity to explain the results of completing it, will argue that an accurate, authenticated forecast will provide the basis for making a sound first estimate of future resource requirements.

Below is your draft of Task 1. The bullets in the middle of this and subsequent tasks are the I-slot material taken from your logic tree.

Task 1: Confirm ABC’s Long-Term Product Forecast

Although ABC already has a forecast by product line, we believe that the engagement must be conducted with Consolidated constantly in mind. Since Consolidated must release the necessary capital funding, it must be convinced of the engagement’s rigor and robustness. For that reason, we believe that the forecast must be confirmed by an independent third party. Therefore, we propose to work with ABC’s marketing management to confirm or modify the long-term forecast by:

![]() validating ABC’s current overall market forecast

validating ABC’s current overall market forecast

![]() validating ABC’s market share and your geographic and product-mix projections

validating ABC’s market share and your geographic and product-mix projections

The consensus market forecast developed in this task will represent the best thinking of your marketing group and the Paramount team. The forecast, used with various manufacturing data, will enable the engagement team to develop future resource requirements over time.

Composing the P-Slots for Task 2: Determine Total Factory Resource Requirements at Alternative Forecast Levels

Your initial meeting with ABC’s buying team and Gilmore’s description of the current operation have given you a high regard for ABC’s capabilities. But you also realize that even competent managers can be so close to their operations that they risk taking them for granted, not fully recognizing opportunities for improvement. You also know that ABC hasn’t been involved in planning a new facility for years and probably doesn’t recognize that facility needs can be either seriously overstated or understated without first establishing a solid base of effective operations from which to project those needs.

These are points you develop to formulate an opening P-slot for this task. Importantly, the task will involve identifying opportunities to improve current operations and/or outsource various components to establish a solid base that will be used in conjunction with the forecast to accurately project future requirements.

You know that the output from this task will provide an essential ingredient for developing the overall manufacturing facility strategy. Only when future requirements are known can the study team explore viable options for providing these requirements. You convey this important understanding in the closing P-slot.

Your draft of Task 2:

Task 2: Determine Total Factory Space Requirements

at Alternate Forecast Levels

An important task of the engagement team will be to use the existing base of production resources (floor space, equipment, and staffing) and modify that base so that it can accommodate the additional future production demands over time indicated by the confirmed market forecast. First, however, the team will carefully evaluate that base to identify improvements or eliminate inefficiencies that might exist today. We don’t want ABC to risk adding too much or too little capacity. This risk can be avoided by first establishing a proper base, a “current-improved” base, from which to project future resource requirements. All this will be critical, because determining future needs involves far more than simply an arithmetic extrapolation of today’s activities.

We were very much impressed during our walk-through of your main manufacturing facility. You should know, however, that in nearly every similar engagement, we have been able to recommend methods for better utilizing currently available space, thereby making space available for additional equipment to add to manufacturing capacity. To provide additional capacity and/or space without first determining such improvement opportunities could result in unnecessary capital investment.

We will ensure that ABC is making the most effective use of existing manufacturing resources. Specifically, we will:

![]() document current equipment and space utilization

document current equipment and space utilization

![]() determine opportunities to better utilize current equipment and space and to improve material flow

determine opportunities to better utilize current equipment and space and to improve material flow

![]() determine opportunities for utilizing new equipment technology

determine opportunities for utilizing new equipment technology

![]() specify which products or components, if any, could be made in-house or purchased from suppliers

specify which products or components, if any, could be made in-house or purchased from suppliers

The modified, effective base of production resources coupled with the confirmed market forecast will enable the engagement team to develop an accurate and credible projection of future resource requirements. At this point, the joint ABC/Paramount engagement team will have a sound basis for identifying, evaluating, and selecting the most viable option or options to provide these requirements.

Composing the P-Slots for Task 3: Define Manufacturing Facility Options to Provide Required Resources

Many different facility configurations could provide ABC’s needed additional resources. ABC’s management team understands this as well: Metzger felt that the existing facility should be expanded, Gupta thought the same for the satellite facilities, and Collins argued for a “greenfield” site closer to expanding markets. You try several times to write P-slots for this task, but each of them sounds forced and dry. Eventually, you realize why: The fundamental purpose and result of this task are so obvious that opening and closing P-slots are unnecessary. So you introduce this task with nothing more than a transition from Task 2 and end the task’s discussion with a transition to Task 4.

Your draft of Task 3 reads as follows:

Task 3: Define Manufacturing Facility Options

to Provide Required Resources

Once we know how much additional space and equipment are required, we will identify the possible manufacturing options that will provide these additional resources. Accordingly, we will develop and analyze various options and determine which configuration of facilities best meets your objectives.

Specifically, we will:

![]() determine expansion potential at the current facility

determine expansion potential at the current facility

![]() specify potential factory roles and locations for increasing capacity

specify potential factory roles and locations for increasing capacity

As a result of completing this task, we will have narrowed the field from the possible to the probable, the better to be able to scrutinize the remaining options and to choose the most appropriate.

In rereading your draft, you realize that the second bullet probably should have some discussion under it.

Composing the P-Slots for Task 4: Select the Most Appropriate Option

This task will help eliminate the uncertainty that must be disconcerting to ABC’s team. It will reveal whether Metzger’s, Collins’s, or Gupta’s biases are valid. But in the process, you know that a number of “pet” ideas are going to be “shot down.” Only considerable agreement among the buying team on the criteria to be used to evaluate the multiple options will avoid hard feelings and assure acceptance of the selected facility option. These thoughts, which also focus on the theme of consensus, help you formulate an opening P-slot.

For the closing P-slot, you focus on two crucial results of completing the task: first, ABC will know precisely how to configure its manufacturing facilities over time; second, the result of proper configuration will allow ABC to meet customer demand throughout the forecasted period cost-effectively and responsively.

Your draft of Task 4 reads as follows:

Task 4: Select the Most Appropriate Option

Using ABC’s distribution model and Paramount’s proprietary models for assessing expansion options, the joint engagement team will evaluate thoroughly each potential expansion option and then select the one most appropriate. Although the range of options will have been narrowed, those remaining will quite likely be diverse. Therefore, we will work with ABC management to develop both quantitative and qualitative criteria that will differentiate carefully among the various options, and we will obtain management’s agreement on the one most appropriate.

Specifically, to select the most appropriate option, the engagement team will:

![]() define quantitative and qualitative criteria important to ABC and Consolidated

define quantitative and qualitative criteria important to ABC and Consolidated

![]() evaluate each option against quantitative criteria such as ROI, landed cost, quality, and customer service

evaluate each option against quantitative criteria such as ROI, landed cost, quality, and customer service

![]() evaluate each option against qualitative criteria such as manufacturing flexibility and potential risk

evaluate each option against qualitative criteria such as manufacturing flexibility and potential risk

When this task is completed, you will know precisely how to configure your manufacturing facilities over time so that you can meet customer demand throughout the forecasted period cost-effectively and responsively.

Composing the P-Slots for Task 5: Develop a Plan to Implement the Selected Option

Merely defining the best facility option for ABC won’t be enough. They will need to know precisely how to implement the selected strategy, and they will look to Paramount to provide that direction. Since space, equipment, new technology, and people probably will be added in stages during the forecast period, ABC will want to know just when and how much new capital and additional manufacturing resources will be needed over that time period. You feel confident that carefully worded statements based on this need will provide an impressive opening P-slot.

Your closing P-slot will stress that completing this task is most important to ABC. It will provide them with an accurate, carefully defined road map showing precisely how to implement the facility strategy in a timely, efficient, and cost-effective manner. The draft of the final task looks like this:

Task 5: Develop a Plan to Implement the Selected Option

Because the additional manufacturing resources required will likely be brought onstream at various times throughout the forecast period, ABC will need a carefully prepared plan to monitor progress during implementation. To that end, we will prepare a plan to ensure that additional manufacturing resources and facilities are in place when and where they are needed to meet forecasted demand. The various steps in our implementation plan will be time-phased so that management will know precisely when additional capacity is required and when other managerial decisions and actions are needed.

Specifically, we will:

![]() define the tasks necessary to implement the selected option

define the tasks necessary to implement the selected option

![]() define the resources and responsibilities necessary to complete those tasks

define the resources and responsibilities necessary to complete those tasks

![]() develop a critical path to estimate the time required to complete all tasks

develop a critical path to estimate the time required to complete all tasks

As a result of this task, management will know all the tasks required to provide the additional manufacturing resources, when each task should be initiated and completed, and the skills required to complete each task. The implementation plan will provide you with a critical mechanism to monitor overall progress, to efficiently invest required capital and other resources when they are needed, and to take corrective actions if actual market demand differs significantly from that projected.

After completing this task and obtaining your agreement, we will work with you to immediately prepare a capital appropriations request that can be submitted directly to Consolidated for their timely consideration.

Because the closing P-slot for Task 5 discusses some of the project’s major outcomes (an implementation plan and a capital appropriations request), you decide to use it as well for the closing P-slot of the entire section.