APPENDIX G

Reading RFPs

If you want a quick sense of how many different kinds of proposals there are, you should search Amazon.com using the key words proposal writing, as I did a few months ago.1 Thirty-three of the three dozen bestselling books, including this one, focused on specific kinds of proposals: business proposals, consulting proposals, sales proposals, grant proposals for university researchers, grant proposals for notfor-profit community organizations, and dissertation proposals. You’d be amazed at the specific focus of these books—for example, an entire book on obtaining funding for nursing research and another on obtaining funding for spatial science research. These last two books were among the top-36 bestsellers! Many more scholarly nurses and spatial scientists must exist than I (and, I bet, you) ever imagined.

Only three books focused on proposals in general. One was clearly marketed as a textbook rather than a trade book. Another, The Zen of Proposal Writing, focused on a particular approach for writing proposals as well as, we can assume, everything else.

A good reason exists for the large number of books that focus on specific kinds of proposals rather than on proposals in general: Although all proposals have the generic structure slots SITUATION, OBJECTIVES, METHODS, QUALIFICATIONS, COSTS, and BENEFITS, the subgenres are very different. Writing Winning Business Proposals is incredibly helpful in writing business (and, more specifically, consulting) proposals, but only about 80 percent of this book’s content would help you write various kinds of grant proposals. Generalizations about proposals can be useful. They can also be dead wrong.

The same can be said for books and articles that generalize about requests for proposals (RFPs). A book on responding to guidelines from the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, or the National Endowment for the Humanities won’t be much help to you if you are a consultant who wants to know how to respond to an RFP from a prospective client. Books and articles that focus on specific kinds of RFPs in specific situations tend to overemphasize the importance of RFPs. The author of one of those books believes that by simply receiving an RFP, a firm is so advantaged that it should ask, why wouldn’t we devote the necessary resources to respond?

Well, for many reasons, not the least of which is that selling consulting work via RFPs is a relatively low-value, high-risk exercise. As an example, consider these two scenarios, in both of which you are a consultant. In Scenario 1, you build a trusted relationship with a senior-level potential client, working closely for weeks if not months with the prospect’s team to develop custom-made objectives and methods for addressing one of the firm’s agreed-to problems or opportunities. At the same time, you are creating barriers to entry for other consultancies, many of whom are unaware of this particular sales process in the first place. The eventual proposed engagement has a price tag of more than US$1M. If you win (and your hit rate in such situations is greater than 70 percent), you can expect considerable follow-on work because your pricing strategy builds in “face time” during the engagement to deepen your relationships, allowing you to uncover additional opportunities, perhaps none of which will require competitive bidding.

In Scenario 2, your consultancy receives on Monday an RFP “over the transom.” Not until Wednesday does that document get to you, the subject-matter expert who can address the objectives indicated in the RFP. Not until Friday can you assemble a team whose responsibility is to respond. Because the proposal is due the following Monday, your team writes it over the weekend and delivers it without a single conversation having taken place between you and the potential client. You are one of 15 bidders. The RFP was written by the incumbent, who tailored the requirements to the incumbent’s strengths. You and 13 other bidders are column fodder. That is, on the prospect’s evaluation sheet, the incumbent is listed in column one; every one else owes their existence to due diligence or legal requirements. Those consultancies in the other columns have little chance of winning. The engagement will be a “one off” with little likelihood of follow-on work. All the consultant-selection team are middle managers, and there will be no opportunity to sell upward, either during the current engagement or during subsequent ones, should they even exist. Given the relatively low-level scope of the work, your bid will be less than US$60K, and given the large number of competitors, your hit rate in such situations is at best less than 25 percent.

Of course, these are extreme scenarios, but they are not unlikely ones: They happen all the time, and I hope you’ve had considerable experience with the first one. Nevertheless, there are many reasons for responding to an RFP. First, business might be in a lull, and you have many people on the beach (i.e., unengaged) with little to do; therefore, you want them to acquire proposal-writing experience. Second, the RFP might have come from a firm that knows little about your consultancy, and although your odds of winning this opportunity are small, you wish to respond, using the proposal as a marketing tool. Third, assuming the Pareto Principle (the 80/20 rule), 80 percent of your revenues likely come from 20 percent of your clients (like the prospective client in Scenario 1), and much of that remaining 20 percent of revenues—in my experience, anyway—is RFP-driven (as in Scenario 2). Those revenues keep the lights on and get the garbage collected. Finally, RFPs have become increasingly important in consulting.

In the late 1990s, one of the consulting industry’s most lucrative “products” was strategic sourcing, which helped clients to source required components through competitive bidding, thereby reducing costs for products and material they did not make in-house but outsourced from a variety of suppliers. The vehicle by which those components was sourced was the RFP. Ironically, during the first decade of this century, businesses began to apply to consultants similar practices taught them by the consultants themselves. Long a function in government contracting, procurement (which suddenly included procuring consultants) became an important function in the corporate sector.2

Given the growing importance of consulting RFPs, you need to learn how to respond to these documents and, therefore, how to read them strategically. I’ll show you how, if you’ll follow these three steps:

![]() Read for the logics.

Read for the logics.

![]() Read for the psychologics.

Read for the psychologics.

![]() Strip all the requirements, including those not named as requirements and not in the RFP’s section on requirements, and test your proposal’s content against those requirements.

Strip all the requirements, including those not named as requirements and not in the RFP’s section on requirements, and test your proposal’s content against those requirements.

Step 1: Read for the Logics

As you know, having read the first section of this book, the logics will involve many of the technical elements of the RFP and your team’s response to them in the proposal. I’m not going to talk about this step, for an obvious reason: If you don’t have the subject-matter expertise to understand and respond to the RFP’s technical requirements, you’re whistling in the dark and have little reason to bid.

Step 2: Read for the Psychologics

As you also know, the psychologics includes those elements of persuasion other than logic itself—the heart rather than the head, the emotional rather than the technical—and a key element of the psychologics is your buyers’ hot buttons, which I have defined as an individual’s desires or concerns that can affect the engagement. In Scenario 1 above, as in the ABC case, hot buttons are not often written and not always articulated. You have to intuit them, ferret them out, read between the lines of the spoken.

In RFPs, your buyers’ hot buttons can be identified thematically as repeated words and phrases that express their desires or concerns. Here’s an example:

A European office of a major consultancy, call it ACME, was doing poorly, and many of its consultants were on the beach. A nearby teaching hospital had issued an RFP to 15 firms, but not to ACME, which had no health-care practice. Hearing about the RFP by chance, ACME decided to bid, for two reasons. First, many of its currently unengaged consultants would acquire important experience in proposal writing. Second, the office’s strategic direction involved establishing a health-care practice; if, by chance, they were awarded this lucrative contract (more than US$1M), they would be able to hire sufficient experts to build a practice.

In reading the RFP carefully, ACME’s consultants noticed a subtle but frequent refrain suggested by phrases like professional development and knowledge transfer. Recognizing that a hot button can be addressed by changing the project’s methodology and/or its project staffing, they built into their methodology significant training and knowledge-transfer components, and they included in their project staffing two U.S. subject-matter experts who would relocate during the entire engagement.

Several years and millions of dollars of follow-on work later, ACME asked why their initial proposal was accepted. Because, they were told, none of the other 15 bidders had proposed a methodology with such a comprehensive professional-development component. This hot button had been expressed in the RFP; ACME had not made it up. But everyone else had failed to see it.

In just a minute, we’ll analyze in some detail how one consulting team responded to an RFP, but first some caveats. When reading an RFP, it’s important to think of yourself as an anthropologist and to consider the RFP document a cultural artifact. You need to ask, “Whose culture?” and “Whose artifact?” That is, addressing possible hot buttons could create serious problems if:

![]() The RFP was written by lower-level staff whose desires and concerns are different from those of the buyers.

The RFP was written by lower-level staff whose desires and concerns are different from those of the buyers.

![]() The RFP was written by an incumbent, and the document reflects the incumbent’s rather than the buyers’ culture.

The RFP was written by an incumbent, and the document reflects the incumbent’s rather than the buyers’ culture.

Only if the RFP is written by the buyers, or by those who correctly express the buyers’ desires and concerns, can you be relatively sanguine that identifying and analyzing the hot buttons will help you. That was the case in the RFP we’ll talk about now, as we examine what the consultants did—or didn’t do—in responding.

The RFP requested consulting support for a pharmaceutical company that wanted to improve the analysis of its marketing mix (in this case, its portfolio of drugs) so that its brand teams (those responsible for selling the drugs) could use their resources (for example, their sales teams) to maximize sales.

The 11-page, single-spaced RFP included the following elements:

![]() the history of the existing problem and the ongoing attempts to solve it (pp. 1–3)

the history of the existing problem and the ongoing attempts to solve it (pp. 1–3)

![]() the existing problem and its ramifications (pp. 3–5)

the existing problem and its ramifications (pp. 3–5)

![]() the engagement’s objectives (pp. 5–7)

the engagement’s objectives (pp. 5–7)

![]() the requirements to be met, divided into five sections, such as “project administration” and “products to be covered” (pp. 7–11)

the requirements to be met, divided into five sections, such as “project administration” and “products to be covered” (pp. 7–11)

Some of the possible hot buttons were “consistency,” “empowerment,” and “collaboration,” and they could be combined into this narrative: The consultants had to work collaboratively with the buyers to develop a consistent framework across the organization that would empower the brand teams to make effective decisions in allocating their resources. These words and their variations (for example, empowering, collaborative, and consistent) occurred on the following pages, none of them among the sections listing requirements:

![]() consistency: pp. 2, 3 (twice), 4, 5, 6 (twice)

consistency: pp. 2, 3 (twice), 4, 5, 6 (twice)

![]() empowerment: pp. 3, 4 (twice), 5

empowerment: pp. 3, 4 (twice), 5

![]() collaboration: pp. 2, 3 (twice), 4 (twice), 5, 6 (twice)

collaboration: pp. 2, 3 (twice), 4 (twice), 5, 6 (twice)

You already know that such hot buttons can be developed into themes and placed strategically throughout your proposal: for example, in the background section, the expression of the need for consistency; in the opening P-slot of methods, a rationale for how the methodology is designed to ensure consistency; and similarly for the qualifications and benefits sections.

Step 3: Strip All Requirements in the RFP, and Test Them Against the Proposal

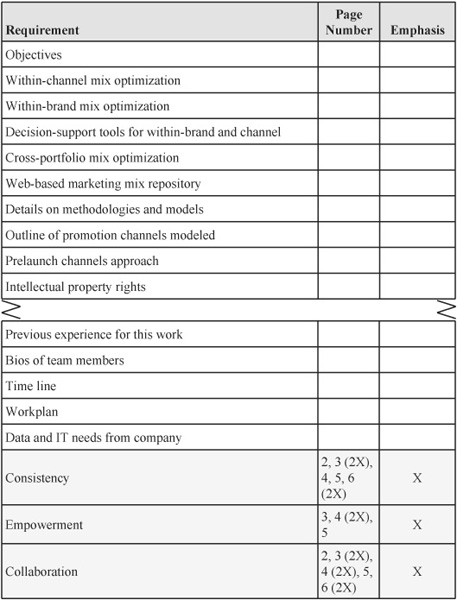

In this step, you need to identify every requirement in the RFP, including requirements not labeled as such, and “strip” them from the RFP by placing them in the first column of a spreadsheet similar to the table in Figure G.1. In additional columns, you can include the RFP’s page number(s) where the requirements are listed and the degree—high (H), medium (M), low (L), or not at all (X)—to which they are emphasized in the draft of your proposal and, if appropriate, in the slide deck for the oral presentation.

All but Figure G.1’s first row and its last three contain requirements from the RFP’s actual requirements sections (which, in total, included more than 50 requirements). The first row’s content comes from the RFP’s objectives section. The last three rows contain the three hot buttons and their degree of emphasis (which was “not at all”!) in the proposal. I’ve added those three rows to illustrate these points:

![]() Although hot buttons aren’t technical requirements important for executing a successful project, they are (de facto) requirements, not only for conducting the project but for selling it, even if the RFP’s writers don’t consider them requirements.

Although hot buttons aren’t technical requirements important for executing a successful project, they are (de facto) requirements, not only for conducting the project but for selling it, even if the RFP’s writers don’t consider them requirements.

![]() The consulting team should have considered them as requirements and addressed them in their proposal.

The consulting team should have considered them as requirements and addressed them in their proposal.

As mentioned often in this book, on a hundred-point scale, the difference between winning and coming in second is frequently as little as two to five points. If the consultants had considered the prospect’s hot buttons as requirements, would they have gained a few points? If they had addressed those hot buttons, would they have won? (They didn’t.)

These questions don’t have easy answers, but this one does: Would it have been worth the consultants’ time and effort to address the hot buttons, thereby increasing the likelihood of their winning and decreasing the odds of their placing a close second?

In the consulting game, even great proposals lose, and even awful proposals win. In fact, in situations like Scenario 1—that is, when RFPs are not involved—great business developers will tell you that proposals themselves rarely win. They either clinch or lose, because the engagement should have been won, or substantially won, before the proposal was even submitted, as a result of relationships and upfront selling. In such situations, the proposal is pro forma, in effect, a legal document serving as a contract. In RFP situations, however, proposals play a critical role in winning the work. As I mentioned above, they also can be responsible for much of the 20 percent of the revenues that keep on the lights. And we know how important that is, since only very few things get done in the dark.

FIGURE G.1 An example of requirements, even those not labeled as requirements, stripped from an RFP