APPENDIX D

Internal Proposals (Make Certain They’re Not Reports)

Let’s consider a situation that might have occurred at the ABC Company, the appliance manufacturer we’ve discussed throughout the work sessions. Let’s assume that Marcia Collins, Vice President of Marketing, has completed her market forecast and therefore believes that ABC will soon run out of manufacturing capacity. Consequently, she has several meetings with Paul Morrison, the Chief Industrial Engineer, to discuss manufacturing and distribution costs, customer service as it relates to capacity utilization, and various scenarios for increasing capacity. As a result of these discussions, Collins decides to “propose” a different way of utilizing existing capacity, and so she meets with Anil Gupta, Vice President of Operations, to discuss her ideas. Very much interested in and intrigued by that discussion, Gupta suggests that Collins develop a proposal that the two of them could present to President Ray Armstrong.

Gupta suggested a proposal. Will Collins, in fact, be preparing one? To answer that question, we need to understand the major difference between proposals and reports. Proposals argue: “This is how we would go about answering your overriding question.” Reports (more specifically, final or recommendation reports) argue: “This is our answer to your overriding question.” That is, proposals look ahead to a methodology that will be performed; reports look back to a methodology that has been performed. Therefore, to determine whether the product of Collins’s efforts will be a proposal or a report, we need to know what Armstrong’s overriding question is and whether Collins’s presentation will answer it or already has answered it.

Let’s assume that Armstrong’s overriding question is similar to the one Paramount Consulting has defined: “How should ABC provide the additional manufacturing capacity needed within the next few years to meet forecasted demand?” Will Collins’s presentation answer that question? Because she has already determined “a different way of utilizing existing capacity,” the answer is “Yes.” Armstrong’s question is “How?” Collins’s answer is, “This is how.” Collins will be preparing a report, not a proposal.

Why is all of this important to you? Because proposals and reports are tools that attempt to achieve very different purposes: for proposals, to explain how you will answer a question; for reports, to present the answer. You would no less want to write a proposal that actually answers a reader’s overriding question than you’d want to use a chain saw to pound in a nail. Unfortunately, many people confuse these two common genres (or kinds of communications) for at least three reasons.

First, the two genres share several common elements. Proposals and reports both contain situation, objectives, methods, and benefits slots, though the tense in these slots is different. For example, a proposal presents me with your understanding of what the situation is; a report reminds me what that situation was. A proposal presents the objective yet to be achieved; a report reminds me what that objective was. A proposal describes the methods that will be used to achieve the objective; a report describes the methods that were used to achieve it.

People also confuse the two genres for a second reason: the similarities between the terms propose and recommend. You can propose a solution, and you can recommend a solution. However, given the concepts we have discussed throughout this book, you can’t really “propose” a solution; you can only recommend one. If you propose a solution, you’ve already found one, and therefore you’re not proposing at all; you’re reporting. You are recommending, on the basis of some analysis or study that you have already completed, the answer to a question. You are not, as you would be in a proposal, proposing a method—before a study—that will derive the answer. Because of the similarities between the terms propose and recommend, many managers ask their subordinates for a proposal even though they are, in fact, requesting a report. So if you’re asked to prepare a proposal, as Gupta asked Collins to do, consider whether your task is to cut down a tree or to sink a nail. Then you can decide whether you need a chain saw or a hammer.

Third, people confuse the two genres because although they have completed a study and answered an overriding question, they’re often not aware of having done so. For example, suppose that you work in my firm and our organizational structure is less effective than you believe it could be. In your spare time, you’ve been thinking about this problem off and on for months—as you daydream at work, when you shower at home, and so on. And over these months, you’ve doodled several possible organizational structures, one of which you believe is better than the current one. You decide to write a document to me that “proposes” the new structure.

I didn’t tell you to do your little study; no one did. And you really didn’t tell yourself to do it, either. You “studied” our current organizational structure by having lived within it. You observed it and analyzed your observations, and you did so probably without realizing that you had. But clearly, you have answered a question: “How can my company more effectively organize itself to achieve our various goals?” If that is also my question and you can support your answer logically and persuasively, you have a good chance of convincing me of your report’s recommended solution. But you’ll be less successful if you try to write a proposal. To take just one example, you’ll spend much time trying to figure out how to construct a methodology that will answer the overriding question you’ve already answered.

In summary, then, reports and proposals are different because they serve different purposes, but they are also similar enough that people sometimes request one when they really want the other, and writers sometimes try to write one when they ought to be composing the other.

Now that we understand how reports differ from proposals, you probably want to know how to write them better. Unfortunately, that would require another book, something like Writing Winning Business Reports. I don’t have time to write that book right now. But I can offer you some tips that build on the concepts I’ve already presented to help you logically structure proposals.

Organizing the Body of Your Report: The Single Recommendation

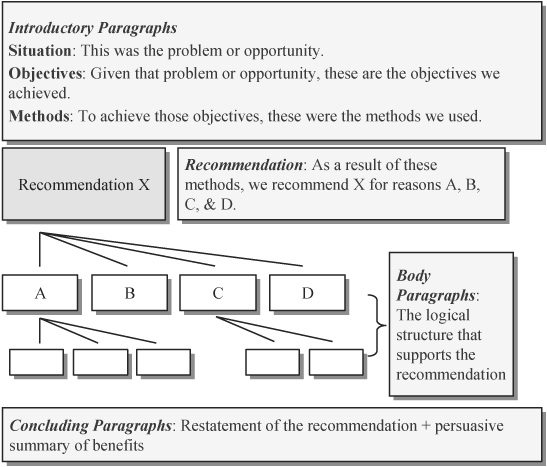

You already know the best tool you can use to organize your report: a logic tree. As we discussed in Chapter 5, a “how” logic tree can be used to organize the actions in your proposal’s methodology. As we discussed in Chapter 11, a “why” logic tree can organize a qualifications section. Reports use both kinds of logic trees. Whereas logic trees can be helpful in organizing a proposal’s entire qualifications section or a part of the methodology, a single logic tree can help you structure the entire body of a report. The examples in this appendix all use “why” logic trees. Be aware, however, that although most recommendation or final reports support their claims by answering “Why?” at the top level of the logic tree, lower levels can answer other questions, such as “How?” and “What kind of?”

To understand how to build a logic tree for a report, let’s assume that Collins has decided to recommend that ABC increase capacity at the current site by expanding the current facility (call this Option A). As Figure D.1 illustrates, the entire body of her report could be a “Why?” logic tree organized to provide evidence and support for that recommendation.

The logic tree is designed to answer Armstrong’s questions as he engages in the report’s dialogue. His first question is the overriding one, related to how best to provide additional capacity. The top box, the report’s major recommendation, supplies the answer: “Expand the current facility to increase capacity.” This recommendation, however, generates another question: “Why?” In Figure D.1, the boxes on the next line provide the answer, in the form of three good reasons. The report’s major argument, then, comprises the recommendation and the good reasons that justify and support it. Each of these good reasons, however, probably necessitates an additional argument, because in his dialogue with the report, each good reason again causes Armstrong to ask “Why?” for justification. If Armstrong needs no further justification, the logic tree below will suffice. If he does need further justification and desires to search more deeply for the underlying rationale, the report would continue building arguments at lower levels. When do the arguments end? When Collins believes that all of Armstrong’s questions have been answered.

No matter how far down the logic tree goes, each box on every level contributes to validating the logic tree’s major claim: Option A is the most appropriate possible recommendation.

FIGURE D.1 In a report, the top lines of a logic tree usually answer the question “Why?”

Now, let’s look at a much more traditional and frequently presented structure that I have seen in many reports submitted to me and that, perhaps, you have used. Note how this reporting structure, in Figure D.2, is much more difficult to understand using the writing patterns typically found in most reports.

Here, the boxes on the second level don’t answer any clear-cut question that could be posed after hearing or reading the recommendation. The body of the report contains separate buckets for findings, conclusions, and recommendations. The findings bucket typically consists of a data dump of facts and figures. The conclusions bucket usually contains a large number of conclusions that are difficult to connect to the previously discussed findings. To make matters worse, in reading some reports, I don’t even know the recommended answer until I’ve been overwhelmed with findings and conclusions. Then I’m subjected to a recommendations bucket and forced to tie together previously presented information to determine whether the recommendation is supported.

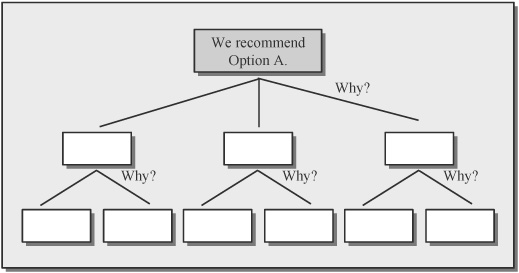

When you use a logic tree, however, the categories of findings and conclusions are irrelevant. Instead, you just focus on answering at any level my question on the level above. Embedded within the argument may be the notion of “better” or “best.” That is, Option A may be preferred because it is at least better in some ways than other options, and overall it’s the best of all possible options. Therefore, the boxes on your second line, as shown in Figure D.3, might express these comparisons: “A is more cost-effective” or “A is easier to implement.” Even if your argument is that “A is cost-effective,” the implication may remain that Option A is more cost-effective than something else. Therefore, you should be certain that the argument supporting the claim “A is cost-effective” considers the relative, not just the absolute, value of the recommended alternative.

FIGURE D.2 The traditional structure of a report

FIGURE D.3 Sometimes your arguments need to be relative rather than absolute.

Organizing the Body of Your Report: Multiple Recommendations

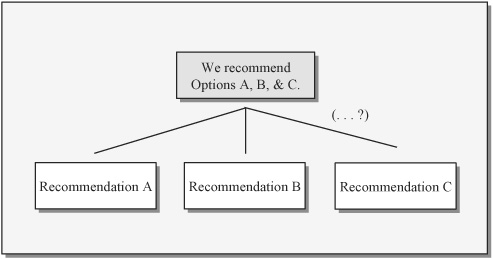

Let’s assume that Collins’s answer to Armstrong’s overriding question is not to increase capacity at the current facility only. Instead, her recommendation has three parts: Increase capacity at the current facility, increase capacity at one of the satellite facilities, and outsource certain components from suppliers. Faced with this three-part recommendation, Collins may have a tendency to build a logic tree like the one in Figure D.4.

FIGURE D.4 An illogically constructed logic tree for a multipart recommendation

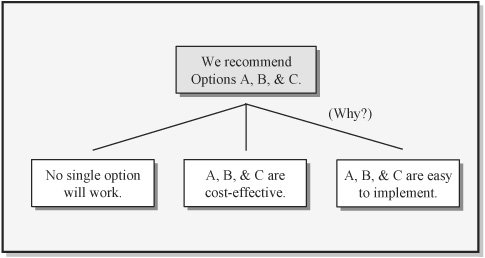

Here, the same problem exists that affected the logic tree organized by findings, conclusions, and recommendations: The logic tree provides Armstrong with no clear answer after he reads or hears the recommendation. This logic tree could prove the validity of Recommendation A, the validity of Recommendation B, and the validity of Recommendation C. However, it does not answer the question, “Why the combination of A, B, and C?” That is: “Why this combination of actions?” The logic tree in Figure D.5 does provide an answer.

Organizing the Whole Report

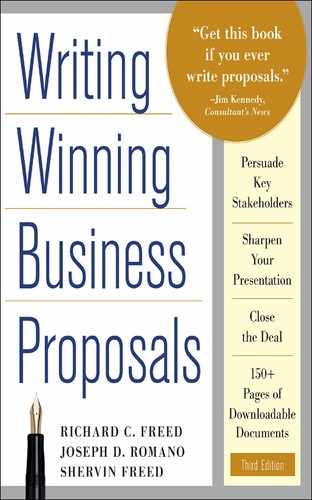

As Figure D.6 illustrates, every logic tree row after the recommendation organizes the body of your report, not the whole document or presentation. The recommendation itself, along with its supporting claims, can end the introduction. When the supporting claims are bulleted, they provide a good forecast of the content and organization of the body, which in a longer report would contain sections corresponding to each of the claims on the second row of the logic tree. Before the recommendation, other slots typically are provided in what can be considered the report’s introduction. These slots explain the problem or opportunity necessitating the study, as well as the study’s objectives and methodology. The concluding part of the document or presentation can restate the recommendation and summarize the benefits of acting on it.

Many of the techniques and strategies we’ve discussed relative to proposals are also useful in preparing reports. Generally speaking, a proposal attempts to “sell” a future service; a report “sells” the ideas gained from that service having been provided. Therefore, you still have buyers, not of your proposed future service (because that’s been performed) but of the ideas generated by that service having been performed. As in proposal situations, these buyers play different buying roles in evaluating your report, and they will perceive different benefits based in part on their different roles. These buyers also will have hot buttons, and they will use various criteria to evaluate your recommendation. You might even have competition, in the form of alternative initiatives being recommended by others in your organization: These initiatives might be competing for the same funding you are seeking. In short, in preparing your report, you should find helpful the same concepts and some of the same worksheet cells that are so useful in completing a proposal. There is no magic in writing effective reports. The key is a logical structure that answers the overriding question.

FIGURE D.5 A logically constructed logic tree for a multipart recommendation

FIGURE D.6 In a recommendation report, the logic tree forms the body of the document or presentation.