CHAPTER 9

Writing the Situation and Objectives Slots

In Chapter 1, I said that a well-written proposal isn’t a collection of separate sections or chapters or slots but a coherent argument woven throughout the document or presentation. For this reason, it’s difficult for me, your potential client, to claim that one proposal slot is more important than another. In some situations, cost could be crucial; in others, your own or your firm’s reputation or qualifications; in still others, the methodology, especially when the tasks are numerous and the project’s management will be complex.

But let’s limit the variables. Let’s assume a competitive situation with multiple bidders whose objectives, methods, qualifications, and costs are all similar. Everything else being equal, your competitive edge could lie in the situation slot, which is often formed into a section called “Background” or “Business Issues” or “Our Understanding of Your Situation.”

SITUATION is usually my first significant contact with your proposal and, in some cases, with you. It may be my first significant opportunity to sense who you are, what you believe, how strongly you believe it, how knowledgeable and competent you are regarding my problem or opportunity, and how qualified you are to address it.

Later, you probably will discuss your firm’s qualifications, but from the first word in SITUATION, you’re already displaying (or not displaying) your abilities and projecting (or not projecting) a desirable image of you and your firm. You’re already demonstrating (or not demonstrating) that you know my industry, organization, issues, and culture and that you can come into my organization, interact with a wide variety of people, sift through masses of often conflicting information, and achieve our objectives. If you demonstrate all that, by the way, you’ll be displaying your qualifications much more persuasively than most qualifications sections can.

Here’s an example of a brief background section that contains three components that we’ll discuss below:

A long time ago, in a galaxy far far away, Darth Vader and the evil Empire sought to conquer all of galactic civilization, despite the efforts of the heroic Rebellion to thwart their attempts at every turn. Through the extraordinary efforts of Princess Leia and R2D2, we now have intelligence that the Empire is building a so-called Death Star capable of demolishing an entire planet within minutes. If the Death Star is not destroyed, the Empire will enslave every citizen of the galaxy.

Despite the Death Star’s blueprints brought to us by Leia, we still have many questions that must be answered:

![]() How will the Empire defend the Death Star?

How will the Empire defend the Death Star?

![]() What are its defenses?

What are its defenses?

![]() Where are those defenses vulnerable?

Where are those defenses vulnerable?

![]() What fighting force is required to exploit those vulnerabilities?

What fighting force is required to exploit those vulnerabilities?

To answer these questions, we will develop an implementable plan to destroy the Death Star. Subsequent to implementation, the Empire will lose its strangle-hold on galactic civilization, the Rebellion will triumph, and Harrison Ford will go on to become a bankable Hollywood star.

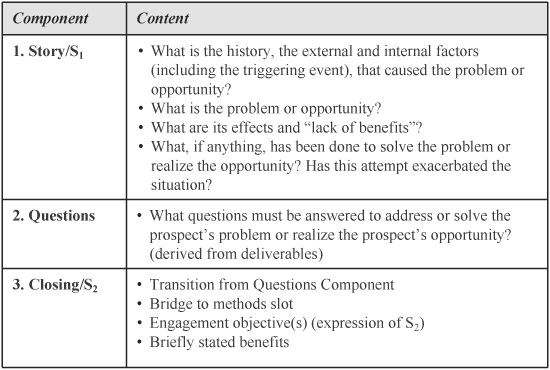

As Figure 9.1 illustrates, the background section above contains three components (one per paragraph): Story/s1, Questions, and Closing/s2.1 Each of these components offers you a significant opportunity to convince me that you understand my problem or opportunity and know what it takes to address it.

The Story Component

To describe your understanding of my current situation, your Story Component should tell me a compelling and engaging story by narrating a sequence of events. Why tell a story? Because I and my colleagues like stories and become involved in them. History is a story. So are biographies, plays, movies, novels, newspaper articles, soap operas, and even jokes. I like, read, and need stories so much that even when I sleep I can’t help but tell stories to and about myself: I dream. Stories are inherently interesting—I’ve never met anyone who didn’t like them. And inherently interesting to me and everyone else on the buying committee is a story about our organization and our current situation. That situation has a history—a past that led to and a present that is affected by the problem or opportunity and, implicitly, a future that will result in our problem or opportunity being addressed, solved, or realized. We have a sense of immediacy about our story, and we want our potential consultants to share it.

FIGURE 9.1 The three components of the situation slot

You be the judge. Here are two sentences that began the situation slots in proposals I received when I was working in the health care industry. Which has more power, more force, more reader interest?

![]() Mercy is a 300-bed hospital in Chicago, Illinois.

Mercy is a 300-bed hospital in Chicago, Illinois.

![]() As Mercy grew to 300 beds, its business objectives began to change.

As Mercy grew to 300 beds, its business objectives began to change.

The first sentence contains unnecessary (and redundant) information: I already know that Mercy is a hospital in Chicago, since the proposal was addressed to Mercy in the first place and I went to work there almost every day. That sentence also portrays all the research abilities and problem-solving skills of a fourth-grader. It demonstrates only that you can find information from an annual report or a company brochure; it doesn’t offer you a good opportunity to begin demonstrating your understanding of my, the reader’s, situation. But even all that doesn’t get to the heart of the matter. The plain truth is that the first sentence is dead. Lifeless. Uninteresting. Boring. Why? Because there’s no time in it, no sequence of causes and effects, actions and reactions. It’s static. It doesn’t move. It’s more like a rock, changeless, than an organization that, like my organization and yours, is a living, breathing organism that constantly changes—and whose changes need to be managed, which will be your job if you win the proposed project.

The first sentence, then, is static; the second, dynamic. The first is inanimate, outside of time. The second is animate; it moves because it contains time and the passage of time—like life. The first contains only facts (facts I already know); the second subordinates the facts to a story. As the beginning of a story, the sentence compels my interest because I want to know what will happen next. I want to know the rest of the plot. Your strategy, then, should be to include in your Story Component the necessary information, the facts, about my organization, but to subordinate that information to your story about my problem or opportunity.

Too often, situation slots are written with the goal of feeding back information to me so that I will know that you have listened. But I want you to do far more than just listen. I want you to demonstrate not only that you have listened but that you have understood—that you can take the information I have given you and analyze it, synthesize it, place it in some context, and even educate me in the process. To demonstrate to me that your project won’t be a data dump of undigested information, there are four questions germane to the Story Component that you can answer:

![]() Causes: What is the history, the external and internal factors (for example, those related to our markets, competition, costs, and processes), that gave rise to our problem or opportunity?

Causes: What is the history, the external and internal factors (for example, those related to our markets, competition, costs, and processes), that gave rise to our problem or opportunity?

![]() Problem/Opportunity: What is the problem or opportunity?

Problem/Opportunity: What is the problem or opportunity?

![]() Effects: What are its effects on me and my organization (the actual ones of not solving the problem, the potential ones of not realizing the opportunity)?

Effects: What are its effects on me and my organization (the actual ones of not solving the problem, the potential ones of not realizing the opportunity)?

![]() Attempted Solutions: What, if anything, has been done to solve the problem or realize the opportunity?

Attempted Solutions: What, if anything, has been done to solve the problem or realize the opportunity?

Answering the first question, about the background, the history, of the situation, allows you to begin your story as you narrate the events that caused the problem or opportunity. These factors can be internal (new company initiatives, changes in management) or external (aggressive moves by competitors, advances in technology, changes in the economic environment). By discussing the internal factors, you can demonstrate your understanding of my company, people, and cultural issues. By analyzing the external factors, you can demonstrate your knowledge of my industry, projects, markets, and competition. When possible and appropriate, you want to educate me about my organization, my market, and my perspectives on the situation. By sharing nonproprietary, comparative information about these factors, you pique our interest and imply your qualifications.

In answering the first question, as well as the second and third, you must keep in mind that my perception of our current situation, and its causes and effects may be different from the perceptions of others on the buying committee. Your goal is to weave a coherent story that incorporates all the buyers’ individual stories. That is, your Story Component needs to narrate the individual perceptions of S1 and their causes and effects. This isn’t an easy task, especially if our individual stories differ significantly. The danger is that the buying committee’s lack of agreement could result in your Story Component’s lack of coherence or consistency.

Frequently, however, you can turn our lack of agreement to your advantage, since lack of agreement on the buyers’ part underscores the problematic nature of our situation and reinforces our need to reconcile disagreement to achieve our desired result, which will remove each buyer’s pain or uncertainty. That is, lack of agreement on the buyers’ part can reinforce our need for an objective third party sensitive to differing perceptions and desires.

The fourth question, on attempted solutions, applies only if we previously have attempted to move from S1 to s2, through either internal efforts or those of consultants. Given that you are being considered for the project, our attempt quite likely was unsuccessful. In this part of the Story Component, you can demonstrate your understanding of what went wrong and, implicitly, what pitfalls therefore need to be avoided.

The following paragraphs contain a brief Story Component from a proposal written some years ago. Note how the writer discusses the external factors that have caused a transition to a deregulated banking environment as well as the opportunities this transition affords. Should she also have discussed the effects? By understanding that the Story Component can contain causes, problem/opportunity, effects, and attempted solutions, you know what you can write into the component, and you can check what you might have unintentionally omitted.

Background

As international standards for capital requirements force liberalization of financial regulations, your organization is challenged by the tremendous transition currently occurring in the Japanese banking industry. Deregulation is leading to heightened competition for domestic banks, and small community and regional banks are threatened by larger, more capital-rich financial institutions. These institutions have already started to increase market share through mergers and acquisitions. To remain competitive, regional banks now face new challenges to obtain new retail customer accounts and to maintain the loyalty of their existing customer base. Through your organization, these regional banks seek innovative ways to differentiate themselves and cope with deregulation to compete profitably against the super-regional Japanese banks.

With this transition to a deregulated banking environment, your community bank consortium has the opportunity to become more innovative and differentiated among the competition in providing products and services not formerly available in the regulated atmosphere.

Where do you get the content for your Story Component? As you might already have guessed (and as you’ll see near the end of this chapter), from Cells 1 and 2 of the Logics Worksheet.

The Questions Component

The Story Component grabs my interest by involving me in a narrative about my organization’s current situation and about how we got to where we are today. It also demonstrates your problem-solving skills by presenting your analysis of my organization’s problem or opportunity. Now, by your asking questions, the Questions Component helps maintain my interest and continues to demonstrate your analytical skills. This component should answer the following question: What key questions must be answered to address the problem or opportunity?

Questions encourage my interest because they help you create a dialogue with me; they invite my engagement and my participation. A spoken statement such as “It’s cloudy today” leaves little room for my response, but a question such as “Is it cloudy today?” invites a response. A statement is convergent; it closes things off. A question is divergent; it creates an invitational pause, allowing me to respond and participate in the dialogue. Because reading or listening is a participatory rather than a passive activity, questions encourage involvement and help me move more thoughtfully through your document or presentation.

One of the most important qualities of a good problem solver (that’s one of the characteristics I want you to possess) is the ability to ask the right questions. As long as scientists believed malaria was caused by bad air (in Italian, that’s what the word means), they were asking the wrong questions and couldn’t determine the cause of the disease. When, however, they asked, “Could it be caused by a microorganism?” they could begin to identify a specific organism and the process of transmission. By identifying the salient issues of our situation and by phrasing them as questions, you demonstrate to me that you can identify those issues and formulate those questions whose answers will help direct us to ensure a successful project.

Questions can provide yet another strategic advantage: They allow you to address a buyer’s issue without your having to take a position on that issue. Consider the situation at ABC. Metzger wants to expand at the current site. Of course, you don’t know at the proposal stage if expanding there is ABC’s best option, but you can let Metzger know that you’re sensitive to that option, that you have heard him, if you use a question like this: “How much expansion potential exists at the current facility?”

Collins and Morrison, in contrast, are more concerned about service levels and distribution costs, which probably would improve if ABC built a new facility closer to the company’s growing markets. You can let Collins and Morrison know that you’re sensitive to their concerns and that you have heard them, if you use questions like these: “Even if resources can be provided at the present location, does it make economic sense to add them there or to make the investment elsewhere? For example, will service levels increase and transportation costs decrease at a new geographic location?” Through these questions, you haven’t come down on Metzger’s side or on Collins’s or Morrison’s. You haven’t alienated any of them by taking a position. In fact, you likely will have satisfied all of them by demonstrating that you’ve listened.

Where do you get the questions for your Questions Component? From either of these:

![]() the deliverables in Cell 5 of the Logics Worksheet

the deliverables in Cell 5 of the Logics Worksheet

![]() the logic tree for your methodology

the logic tree for your methodology

As you saw in Chapter 5, the Logics Worksheet’s deliverables likely found their way into your logic tree, each of whose actions need to express a deliverable. So if you have already constructed your logic tree, you can derive your questions from it. For example, consider the logic trees for the proposal to XYZ in Chapter 5 (which I’ve included again as Figure 9.2).

The second row of the figure implies that you would answer five key questions to achieve the project’s objectives:

![]() What opportunities exist for XYZ in the information service market?

What opportunities exist for XYZ in the information service market?

![]() What capabilities and resources are required to capitalize on those opportunities?

What capabilities and resources are required to capitalize on those opportunities?

![]() What gaps exist between those required capabilities and resources, on the one hand, and XYZ’s, on the other?

What gaps exist between those required capabilities and resources, on the one hand, and XYZ’s, on the other?

![]() What actions are required to close those gaps?

What actions are required to close those gaps?

![]() What resources and how much time are necessary to close the gaps?

What resources and how much time are necessary to close the gaps?

Note the strategy here. A Questions Component like this not only provides evidence for your problem-solving ability, it also prepares me for your methodology. If I buy into the questions in your situation slot, you have gone a long way toward preselling your methodology.

Of course, this component could include other questions. You may want to use questions that respond to hot buttons, evaluation criteria, and counters to the competition. Even if you don’t, you could phrase the questions derived from your logic tree so that they address hot buttons and other thematic material. For example, if urgency were a theme, the fourth question above could be phrased like this: “What actions are required to close these gaps within the limited time frame required?”

FIGURE 9.2 Using your logic tree as a source for the Questions Component

The following passage, which continues the “background” section about the Japanese banking industry, contains a Questions Component:

However, the transition necessary to change from traditional marketing protocols to new ways of marketing bank services will require a structured investigation that answers the following questions:

![]() What are the essential customer needs and requirements that will attract new business opportunities for retail banks?

What are the essential customer needs and requirements that will attract new business opportunities for retail banks?

![]() What product, pricing, and promotional tools are necessary to implement and support effective marketing plans, new product development, and delivery systems?

What product, pricing, and promotional tools are necessary to implement and support effective marketing plans, new product development, and delivery systems?

![]() What types of technology and systems support are necessary to administer new products, services, and marketing efforts?

What types of technology and systems support are necessary to administer new products, services, and marketing efforts?

![]() What marketing strategies have successful regional banks in the United States used since deregulation, and what performance levels have resulted from implementing those strategies?

What marketing strategies have successful regional banks in the United States used since deregulation, and what performance levels have resulted from implementing those strategies?

Before I can make the transition from S1 to S2, your project will have to answer important questions. Articulating them in the Questions Component suggests to me that you will be able to do that. Framing these questions also forces you to think hard about your project’s issues, assumptions, and hypotheses.

![]() What are the key issues that must be resolved?

What are the key issues that must be resolved?

![]() Which issues are crucial, and which are tangential?

Which issues are crucial, and which are tangential?

![]() Given the crucial issues, how will your methodology be designed to resolve them?

Given the crucial issues, how will your methodology be designed to resolve them?

![]() In resolving them, what benefits will accrue to me and my organization?

In resolving them, what benefits will accrue to me and my organization?

The last two questions suggest an important function of the Questions Component: It helps SITUATION speak to other proposal slots, in this case, to METHODS and BENEFITS.

The Closing Component

The function of the Closing Component is to provide a smooth transition from the text above it to the text below it, to state the project’s objective(s), and to conclude SITUATION with a closing oriented toward me, your potential client.

The Closing Component can include briefly stated themes related to hot buttons, evaluation criteria, and counters to the competition. These themes could emphasize your experience, expertise, past performance, or previous relationship with me or others in my organization or industry. Or they could sell certain aspects of your methodology. Depending on the overall length of the proposal, the Closing Component might be two or more paragraphs or a single sentence. Whatever its length, it contains these elements:

![]() Backward transition from the Questions Component

Backward transition from the Questions Component

![]() Forward transition to METHODS

Forward transition to METHODS

![]() Project objective(s)

Project objective(s)

![]() Briefly stated benefits if they are not immediately apparent in the objectives

Briefly stated benefits if they are not immediately apparent in the objectives

For content related to the third bullet above, your project’s objectives, rephrase the overriding question(s) from Cell 4 of your Logics Worksheets or the desired result(s) from Cell 5. For content related to the fourth bullet above, look to the benefits you have included in Cell 6, choosing two to four powerful selling points of your project. Note how the following sentence, which completes the sample background section we have been considering, contains those four elements:

To answer these questions, we have designed an approach for developing a plan that, after implementation, will enable the community retail bank consortium to achieve the benefits of increased competitiveness in the deregulated market.

Putting It All Together: Composing the “Background” Section from Your Logics Worksheet

If you’ve done all the work in Parts 1 and 2, your proposal or presentation is almost ready to write itself slot by slot. First, I’ll show you and explain the “map” (Figure 9.3) for writing your background section. Then, I will follow that map, constructing the first draft of a background section.

For the Story Component

![]() Create the history of the problem from the content of Cell 1.

Create the history of the problem from the content of Cell 1.

![]() Follow with the triggering event, the problem, and its effects from Cell 2.

Follow with the triggering event, the problem, and its effects from Cell 2.

FIGURE 9.3 Using the Logics Worksheet to construct your background section

For the Questions Component

![]() Turn appropriate deliverables from Cell 5 into questions.

Turn appropriate deliverables from Cell 5 into questions.

For the Closing Component

![]() For the objective(s), rephrase the overriding question(s) from Cell 4.

For the objective(s), rephrase the overriding question(s) from Cell 4.

![]() For the benefits, choose two to four appropriate ones from Cell 6.

For the benefits, choose two to four appropriate ones from Cell 6.

By following the map in Figure 9.3, I will “write” ABC’s background section in the next six figures (Figures 9.4–9.9). Each figure has two parts: on the left, the information from a cell of the Logics Worksheet; on the right, the part of the background section I’m writing directly from that cell.

FIGURE 9.4 Writing the Story Component

FIGURE 9.5 Writing the Story Component (cont.)

FIGURE 9.6 Writing the Questions Component

FIGURE 9.7 Writing the Closing Component

FIGURE 9.8 Writing the Closing Component (cont.)

FIGURE 9.9 Writing the Closing Component (cont.)

There you have it: a background section in five minutes! Although what I’ve written is just a first draft, please note these two important points. First, I could “write” the section as quickly as I did because I wasn’t starting from a “blank page.” Second, the page I was starting from contained fully aligned, well-strategized information that, together with my map, I could use to construct a persuasive section.

The Situation Slot and Competitive Advantage

The Story, Questions, and Closing Components allow you to present not only an interesting story but, more important, a thoughtful, logical and persuasive argument. They can help you project an image of yourself as competent, organized, logical, analytical, knowledgeable, thorough, relevant, coherent, insightful, and creative. These are generic attributes of a good problem solver, characteristics that can be presented to me long before a logically written METHODS validates them and a relevant QUALIFICATIONS reinforces them. You are showing me, not telling me, your capabilities within the context of my situation. Showing always trumps telling.

Moreover, after using these components in proposal after proposal, you’ll find that you can compose the situation and objectives slots more easily and quickly because you will have developed a schema, an internal formula or “script,” just as you probably have developed a script for proposals in general. Many proposal writers have difficulty writing background sections because they haven’t developed such a formula. The preceding structure supplies you with that formula. While not a rule, it provides a guideline regarding what kind of information to consider and where to place it.

The components also help you make SITUATION speak to other slots in the proposal. The questions you present relate directly to your stated objectives and your approach to achieving them. The three components will provide implied but convincing evidence regarding your qualifications as a problem solver.

Finally, like an overture in a symphony, SITUATION can initiate the themes developed later, in subsequent slots of the proposal. As a result, your situation slot gets you and your proposal off to a good start as you begin at the beginning to convince me of one of your proposal’s major claims: You know my industry; you know me; you know my organization and its challenges, problems, and opportunities; and you can address them—maybe not as inexpensively as someone else but better.

CHAPTER 9 REVIEW

Writing the Situation and Objectives Slots

The situation slot has three components that help answer a series of questions, as summarized in Figure 9.10.

FIGURE 9.10 The three components of the situation slot

WORK SESSION 7:

Writing the Situation and Objectives Slots for ABC

Before you actually begin to strategize the proposal, Gilmore sends you a memo concerning the formatting, page layout, and other such “requirements” about which he wants you to adhere. You expect this memo because it is his standard operating procedure.

Requirements for the Proposal’s “Look and Feel”

In almost every project, you have heard, Gilmore engages one or more of the buyers in a discussion of the quality of writing in the prospect’s organization. He does so for two reasons.

First, it allows him to understand the culture better. An organization’s documents, he knows, are like cultural artifacts, and embedded in them are important aspects of the prospect’s culture. Are their decision-making documents composed in PowerPoint or in Word? How powerful are the Format Police, those individuals, usually in Marketing, who have spent months developing a consistent document “look and feel” that harmonizes rather than conflicts with the organization’s attempts to support the firm’s branding? To what extent and how often does the prospect, in this case Anil Gupta, use the format requirements, and if he doesn’t, why doesn’t he? What seems to be the expected length of decision-making documents and the reaction to documents whose length exceeds those expectations? For example, does President Armstrong get frustrated by having to read more than an executive summary (as, in Gilmore’s experience, is typical of many CEOs and presidents)?

Second, this discussion invariably leads the prospect to show Gilmore some of the firm’s decision-making documents and, if he is fortunate, some proposals and reports submitted by external consultants for previous projects. By having Gupta comment on such documents and their formatting and quality, Gilmore can make strategic decisions about the format and design of your proposal.

Here are the key points from Gilmore’s memo to you:

![]() Although most of the previous consultants’ proposals and reports were written in PowerPoint and designed in landscape, as are ours, ABC’s internal decision-making documents are in Word and designed in portrait. Their default font appears to be 11 pt. Century Old Style, and the content in their charts appears to be 9 pt. Helvetica Neue. The captions in those charts, however, appear to be 8 pt. Myriad Pro.

Although most of the previous consultants’ proposals and reports were written in PowerPoint and designed in landscape, as are ours, ABC’s internal decision-making documents are in Word and designed in portrait. Their default font appears to be 11 pt. Century Old Style, and the content in their charts appears to be 9 pt. Helvetica Neue. The captions in those charts, however, appear to be 8 pt. Myriad Pro.

![]() Given the above, we need to write our document in Word and in portrait, with 11 pt. Century Old Style as the “normal” font and 9 pt. Helvetica Neue for charts and figures and 8 pt. Myriad Pro for captions. As much as possible, our color schemes/palette should harmonize with their own. To help reinforce the good relationships we’ve developed with ABC’s buyers, the document should be a letter proposal that therefore will allow us to address ABC directly and to use second-person pronouns.

Given the above, we need to write our document in Word and in portrait, with 11 pt. Century Old Style as the “normal” font and 9 pt. Helvetica Neue for charts and figures and 8 pt. Myriad Pro for captions. As much as possible, our color schemes/palette should harmonize with their own. To help reinforce the good relationships we’ve developed with ABC’s buyers, the document should be a letter proposal that therefore will allow us to address ABC directly and to use second-person pronouns.

![]() Given the need to adapt the document to different readers with different attention spans (e.g., Armstrong on the short end and the detail-oriented Morrison on the other), we should keep our methods section relatively brief and place our full-blown methodology in an appendix.

Given the need to adapt the document to different readers with different attention spans (e.g., Armstrong on the short end and the detail-oriented Morrison on the other), we should keep our methods section relatively brief and place our full-blown methodology in an appendix.

![]() Bottom line: When they read our proposal, we want them to feel as if it’s one of their own internal documents, as if we and they are partners sharing the same culture.

Bottom line: When they read our proposal, we want them to feel as if it’s one of their own internal documents, as if we and they are partners sharing the same culture.

In your experience, and to his credit, you believe, Gilmore is the only consultant you know who engages in such strategies. A form of Neuro-Linguistic Programming, these strategies certainly help him avoid situations where the buyers expect parchment and the consultants deliver stone tablets.

Writing the Story Component

Before beginning to write the Story Component, you review the Logics Worksheet that you filled out in Chapter 3, especially Cell 1 (Prospect Profile) and Cell 2 (Prospect’s Current Situation). You also consider the large amount of Story Component material from your and Gilmore’s notes as well as from the extensive in-house research that you’ve conducted. From these notes and research, you know, for example:

![]() Industry unit sales have been fairly stable, and total market forecasts indicate only modest growth.

Industry unit sales have been fairly stable, and total market forecasts indicate only modest growth.

![]() Despite stable industry sales, demand for ABC’s products has been growing consistently, with associated (though modest) increases in market share, because of well-designed, high-quality, and competitively priced products, as well as good customer service.

Despite stable industry sales, demand for ABC’s products has been growing consistently, with associated (though modest) increases in market share, because of well-designed, high-quality, and competitively priced products, as well as good customer service.

![]() Projected demand will soon exceed available capacity.

Projected demand will soon exceed available capacity.

![]() Lack of adequate manufacturing capacity could certainly stall ABC’s growth.

Lack of adequate manufacturing capacity could certainly stall ABC’s growth.

![]() Geographic shifts in both population and households have changed patterns of demand and suggest that to maintain or improve customer service some manufacturing capacity should perhaps be located closer to high-growth areas.

Geographic shifts in both population and households have changed patterns of demand and suggest that to maintain or improve customer service some manufacturing capacity should perhaps be located closer to high-growth areas.

![]() Several expansion alternatives have been proposed, though little agreement exists among ABC’s management.

Several expansion alternatives have been proposed, though little agreement exists among ABC’s management.

![]() A major area of disagreement could be the issue of control versus risk as it relates to expanding at the major facility only, as opposed to increasing capacity at one of the regional facilities or at a new location.

A major area of disagreement could be the issue of control versus risk as it relates to expanding at the major facility only, as opposed to increasing capacity at one of the regional facilities or at a new location.

![]() Consensus exists about ABC’s needing a plan and soon.

Consensus exists about ABC’s needing a plan and soon.

Your task is to paint a picture of the various buyers’ combined perceptions of the current situation as well as their combined perceptions of the related causes and effects. In doing so, you want to be certain that you address several of the buyers’ concerns: Collins’s on customer service and its impact on market share; Armstrong’s on the relationship with Consolidated; Morrison’s on distribution costs and potential use of his model; Gupta’s on the threat of increased operating costs; and Metzger’s on expanding in other than the major facility. You also want to initiate some themes: “Urgency” comes to mind, as does “complexity.” After several drafts, and in a fairly forceful voice cognizant of the threats to ABC’s market share and position within Consolidated, you come up with the following:

The Situation at ABC

Over the past five years, household appliance shipments by ABC and your competitors have been fairly stable, and only modest growth is projected over the next five years in your mature industry. Despite the relative stability of these shipments industry-wide, ABC has managed to increase its share of the household appliance market primarily by producing high-quality products at competitive costs and by being responsive to customers’ needs. As a result, ABC has become a leader in the market and one of the premier divisions within Consolidated Industries.

Your consistent record of success, however, may be threatened. Although your market forecasts indicate that ABC can continue to increase market share, even the conservative forecast clearly shows that projected product demand will exceed your available manufacturing capacity in less than three years. Without adequate capacity, your competitive position will certainly suffer as a result of declining delivery performance, deteriorating product quality, and increasing operating costs.

Complicating the picture, demographic shifts are moving demand farther away from your existing midwestern production facilities. Population and household growth in three geographic regions remote from these facilities have far exceeded that of the Midwest, as well as the nation as a whole.

Undoubtedly, these geographic shifts have contributed to ABC’s increased distribution costs, a major factor in the total landed cost of household appliances. In jeopardy are not only ABC’s operating objectives but your status as a premier division within Consolidated.

Recognizing these threats, your management group has suggested several options for increasing capacity, but little agreement exists about how that capacity should be deployed, and no agreement exists about the amount of capacity required. Consensus does exist, however, in two areas: Additional capacity will be needed, and the time when it will be needed is fast approaching.

Writing the Questions Component

The Questions Component, you now know, provides you with an opportunity to demonstrate your qualifications as a problem solver, as someone who can demonstrate the ability to ask the right questions (the better to supply the correct answers). It also provides an opportunity to address key questions that you believe are on the minds of the various buyers. These questions allow you to indicate to each buyer that his or her desires or concerns have been heard without your having to take a position one way or another. Consider the question “How much expansion potential exists at the current facility?” In posing that question, you would address Metzger’s desire to expand at the current facility without having to indicate at this point whether such a strategy is desirable. Equally important, the Questions Component “speaks” to and prepares the way for your methodology because this component presents key questions related to deliverables expressed as important actions in your logic tree.

You begin with a transition that continues the themes of “complexity” and “urgency” and that also initiates the themes of “thoroughness” and “comprehensiveness”:

Complicating the need to move quickly is the need to carefully develop a thorough, convincing, and comprehensive plan accepted by both ABC’s and Consolidated’s management. This plan should answer questions like these:

![]() Based upon the long-term forecast, how much total factory space, equipment, and human resources are required and when?

Based upon the long-term forecast, how much total factory space, equipment, and human resources are required and when?

![]() What opportunities exist to better utilize current equipment, space, and new technology?

What opportunities exist to better utilize current equipment, space, and new technology?

![]() What manufacturing factory configuration option or options will provide the required space? For example, how much expansion potential exists at the current facility, and what, if any, make/buy scenarios as well as changes in factory roles and locations can provide additional space?

What manufacturing factory configuration option or options will provide the required space? For example, how much expansion potential exists at the current facility, and what, if any, make/buy scenarios as well as changes in factory roles and locations can provide additional space?

![]() Even if resources can be added at the present location, does it make more economic sense to add them there or to make the investment elsewhere? For example, will service levels increase and transportation costs decrease at a new geographic location closer to growth markets?

Even if resources can be added at the present location, does it make more economic sense to add them there or to make the investment elsewhere? For example, will service levels increase and transportation costs decrease at a new geographic location closer to growth markets?

![]() Which option is most appropriate considering the qualitative and quantitative factors identified in our methodology below?

Which option is most appropriate considering the qualitative and quantitative factors identified in our methodology below?

Writing the Closing Component

The Closing Component is rather simple: a short, prospect-oriented paragraph that

(provides a backward transition from the Questions Component . . .) To answer questions like these,

(provides a forward transition that anticipates the methods section . . .) I and my colleagues at Paramount Consulting have designed a methodology

(states the project’s objective . . .) that will develop a manufacturing strategy to provide the capacity necessary for meeting forecasted demand

(and ends with some briefly stated benefits . . .) as well as a concrete plan for implementing that strategy to improve your position within the marketplace and solidify your position within Consolidated Industries.

In rereading all the components together, you’re reasonably satisfied. You’ve supplied good transitions to bridge the junctures between components. You’ve not only initiated the themes, but by doing so, you also have addressed various buyers’ hot buttons while attempting to counter the competition. In general, you believe you’ve been responsive to ABC’s needs. You’ve not only told a good story, you’ve told their story. And, you hope, they will begin to see you as part of it.