CHAPTER 3

Aligning the Baseline Logic

This is the most difficult, perhaps the longest, and arguably the most important chapter in the book. If you skip this chapter, you won’t understand fully most of the book’s subsequent content. So find some blocks of time during which you’re not distracted, and forge on.

Why is this the most important chapter? First, because the baseline logic, introduced in Chapter 2, is the foundation of your proposal, and more than 95 percent of the proposals I’ve read, over the course of 30 years, have serious flaws in the baseline logic, causing serious cracks in their foundations. Second, this chapter demonstrates how you can fully align the baseline logic, as shown in Figure 3.1, and thereby:

![]() Identify substantial content for your proposal that you would otherwise miss

Identify substantial content for your proposal that you would otherwise miss

![]() Assess the clarity (or lack of clarity) in your thinking

Assess the clarity (or lack of clarity) in your thinking

![]() Understand the clarity (or lack of clarity) in my thinking

Understand the clarity (or lack of clarity) in my thinking

![]() Recognize where you and I view matters differently as a first step in having serious conversations about your proposed approach, scope, and projected outcomes

Recognize where you and I view matters differently as a first step in having serious conversations about your proposed approach, scope, and projected outcomes

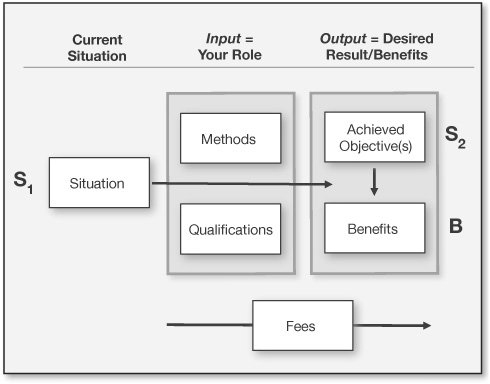

Note two things about Figure 3.1. First, all the new material is just an expansion of what we’ve already discussed: S1 (the current situation), S2 (the desired results), and B (the benefits). On the left side of Figure 3.1 are aspects of the current situation. That’s where you and your firm will begin the change process I desire. On the right side are major project outcomes, including the results I desire and the benefits my organization and I will enjoy. In the middle are the deliverables, those smaller outcomes you will provide along the way as you help us move from one state to the other.

FIGURE 3.1 The fully elaborated baseline logic and its 10 alignments

Second, as you enter content related to these elements into the worksheets (and as you watch the elements entered in this chapter’s work session) you must express the content from the potential client’s point of view, i.e., from my point of view. To help you enter that content, you will want to have next to you all six Logics Worksheet cells, which you can copy from Appendix B. Alternately, you can download and print out those cells as well as the complete Logics Worksheet from http://mhprofessional.com/freed.

What happens if your point of view differs from mine? What happens if my point of view differs from that of other members of the selection committee? What happens if your point of view differs from that of others on your own team? What happens if any of the baseline logic is not aligned? What happens if you don’t know the content to enter on the worksheet or aren’t certain about its accuracy?

The answer to all these questions is the same: You mark that difference, that discrepancy in understanding, with a red flag, which as the downloadable glossary indicates, signals “a weakness, vulnerability, gap in information, or, generally, something you don’t like.” Why should you begin by phrasing the content from my point of view? Because if you don’t, you’ll express your point of view and likely miss mine altogether. Start with me, your potential client, and remember this: You don’t invent red flags; they exist. Red flags don’t express your weaknesses. They signal an opportunity for resolving possible differences, so that, ideally, by the time you write your proposal, your understanding matches mine, and my team’s, and your team’s. Even if you can’t resolve a red flag by the time you need to submit your proposal, you will at least recognize that it exists and make, not a nondecision decision, but a strategic decision based on the flag’s existence.

What follows are crucial questions you need to ask yourself to help you fully align the various elements in Figure 3.1. Below these questions are subsections that discuss each question in some detail:

![]() Are the potential client’s strategic direction, triggering event, overriding problem, and effects/lack of benefits aligned?

Are the potential client’s strategic direction, triggering event, overriding problem, and effects/lack of benefits aligned?

![]() Are the overriding question(s), objective(s), and desired result(s) aligned?

Are the overriding question(s), objective(s), and desired result(s) aligned?

![]() Is the overriding problem aligned with the overriding question(s)?

Is the overriding problem aligned with the overriding question(s)?

![]() Are the deliverables aligned with the desired result(s)?

Are the deliverables aligned with the desired result(s)?

![]() Are the deliverables and desired result(s) aligned with the benefits?

Are the deliverables and desired result(s) aligned with the benefits?

![]() Are the benefits aligned with the effects/lack of benefits?

Are the benefits aligned with the effects/lack of benefits?

Are the Potential Client’s Strategic Direction, Triggering Event, Overriding Problem, and Effects/Lack of Benefits Aligned? (Logics Worksheet, Cells 1 and 2)

Regarding the left side of Figure 3.1, the current situation, you need to understand four vital elements and their alignments.

Strategic Direction

Why strategic direction? Because if you want to have a rich relationship with me, as opposed to just a “one-off” engagement, you want to work on projects that will help my firm achieve our strategic direction. In such projects, your fees will likely be greater (because such projects are more valuable to me), and you will be working at higher levels of my organization, with the very people with whom you wish to develop solid relationships. Accordingly, you want the overriding problem you will address to align with our strategic direction. If it doesn’t, red flag it.

Triggering Event

As defined in the downloadable glossary, the triggering event is that event (in some cases, events) that brought to our consciousness the existence of the overriding problem (or opportunity). A triggering event could be external (e.g., the entrance of a new competitor into my market) or internal (e.g., a change in top management that initiates a whole series of new agendas). Consider the ABC case in Appendix A. What brought to ABC’s consciousness the existence of their imminent shortfall in capacity? Probably Marcia Collins’s market forecast. That forecast triggered, brought to ABC’s consciousness, the need to take action to address the projected shortfall in capacity. If you don’t know the triggering event, you should place a red flag next to that phrase in Cell 2. If the triggering event and overriding problem are not aligned, use a red flag to signal that lack of alignment.

Overriding Problem

“Overriding” means at the highest level, and it means a single problem. My organization has lots of problems, just like yours. For your project with me, however, you need to identify not the major problems but the main one, the single highest-level problem your engagement will address or solve. In expressing that problem in Cell 2, be certain that you phrase the problem as a problem, rather than (as is all too typical) a question. And make certain that it is a single problem rather than “lack of X and insufficient Y.” Assuming that one of those is the overriding problem, the other is likely a cause or an effect. If you don’t know the overriding problem or are uncertain about any aspect of it, use a red flag.

Effects of the Overriding Problem

Problems create further problems. These are the problem’s effects, and your discussion of them in your proposal can be compelling, since we usually sense a problem’s severity by the effects it produces. (I might have the problem of a broken ankle, for example, but I really experience that problem as a result of its effects: pain, immobility, etc.) Use red flags to indicate any lack of alignment between the overriding problem and any of the effects. Also flag any effects that you believe exist but haven’t been confirmed by me.

Are the Overriding Question(s), Objective(s), and Desired Result(s) Aligned? (Logics Worksheet, Cells 4 and 5)

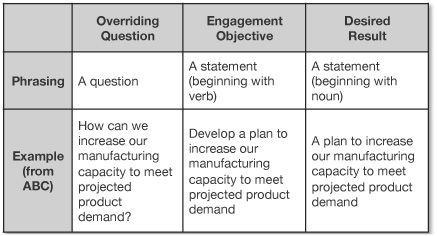

The overriding problem is the beginning point of your project; the three elements on the upper right of Figure 3.1 are the end points, where you will have answered my overriding question(s), achieved the project objective(s), and provided me my desired result(s). These three elements are three facets of the same diamond: They express the same content, differing only in their phrasing, as shown in Figure 3.2.

FIGURE 3.2 The overriding question, engagement objective, and desired result contain the same content, differently phrased.

I can’t tell you how important it is to get the overriding question right. Several years ago, I was playing the role of coach for a team of consultants submitting a proposal to my organization. Before we identified the single overriding question, we listed 24 possible versions, given that I, my colleagues, and the consulting team all had different agendas and conceptions of the overriding problem. Figure 3.3 should give you a good idea of what might happen if the overriding question is wrong. If it is, then the objective will be wrong. If the objective isn’t correct, as we’ll see in Chapter 5, the methodology will be wrong. See if you can answer correctly the question in Figure 3.3.

Given the ABC case in Appendix A, which of the two groupings below best expresses the desires of ABC’s management team?

• Desired Result: A plan to increase internal manufacturing capacity to meet projected product demand

• Overriding Question: How can we increase internal manufacturing capacity to meet projected product demand?

• Engagement Objective: Develop a plan to increase internal manufacturing capacity to meet projected product demand

• Desired Result: A plan to supply product to meet projected product demand

• Overriding Question: How can we supply product to meet projected product demand?

• Engagement Objective: Develop a plan to supply product to meet projected product demand

FIGURE 3.3 The engagement objective depends upon the overriding question.

If your answer is the first grouping, then you have closely read the case in Appendix A. ABC wants to increase its manufacturing capacity. It does not wish to do so in part by outsourcing some of its components. The latter objective would require a project of greater scope because it would involve an extra deliverable: determination of the feasibility of outsourcing. I can think of two of ABC’s responses to the latter objective: first, “You haven’t listened”; second, “You are proposing a more expensive study than what we have asked for.” It’s possible, of course, that ABC could have a positive response: “That’s an interesting objective that we hadn’t considered; perhaps we ought to consider increasing capacity by outsourcing some components rather than making them in-house.” But if you are going to propose the second objective, you had better be certain that, before the proposal has been submitted, you have obtained the required buy-in to avoid the negative responses.

Please note one final aspect concerning desired results, overriding questions, and project objectives. I have defined desired results as “the outcome of the engagement or its phases.” Depending on the type of project (i.e., insight, planning, implementation, or the various combinations) that you circle in the Logics Worksheet, Cell 3, there can be one, or more than one, overriding question and desired result.1,2 As we have already discussed and as is illustrated in Figure 3.4, single-step projects have one of each. As illustrated in Figure 3.5, multiple-step projects have two or more.

Is the Overriding Problem Aligned with the Overriding Question(s)? (Logics Worksheet, Cells 2 and 4)

If you and I don’t agree on the overriding problem and the overriding question(s), we will disagree about where you should begin and where you should end, and we will likely disagree about where you are at every point in the project. This is the territory not just of red flags but of blood-red flags. If you don’t know the overriding problem, that’s a red flag. If you don’t know the overriding question(s), that’s a red flag. If you know neither, you and I are in for a bloodbath. (By the way, this need for alignment is one reason that generic or boilerplate proposals are recipes for disaster.)

FIGURE 3.4 Overriding questions, objectives, and desired results for single-step engagements

FIGURE 3.5 Overriding questions, objectives, and desired results for multiple-step engagements

And even if you know both, they had better be aligned. Their lack of alignment causes more cost overruns (on your part) and more dissatisfied clients (on my part) than perhaps any other aspect of business development.

Are the Deliverables Aligned with the Desired Result(s)? (Logics Worksheet, Cell 5)

I have defined deliverables as the outcomes you produce along the way toward achieving my desired result, and since many people have trouble understanding what deliverables are, here’s an example.3 Assume that your child is a college student in her senior year and that she wants to attend graduate school. Like any good parent, you decide to do an insight study for her. Your desired result is a determination of the best graduate school. This desired result reflects your “study’s” objective: to determine the best graduate school for her to attend. Before you can achieve that objective and that desired result, before you can make that determination, you may desire other information along the way: the cost of tuition and fees; the percentage of graduates who obtain jobs in her academic area; ethnic and religious characteristics of the student body; the kind, availability, safety, and cost of housing; the school’s proximity to cultural activities; the cost and convenience of traveling home; and the like. These are deliverables, the outcomes of your study that you will produce along the way to achieving your desired result.

Of course, some of these deliverables might be important to your daughter and not to someone else who, for example, might not care about cultural activities or ethnic affiliations. And some of these deliverables might be more important to you (or your daughter) than others. Nevertheless, for your and your daughter’s situations, the deliverables must constitute that set of outcomes, no more and no less, that will achieve S2. In other words, the deliverables must be aligned with the desired result.

The project you did for your daughter was an insight study, and, as a result, the deliverables you identified were insight deliverables. It should come as no surprise that there are also planning and implementation deliverables:

![]() Insight deliverables are, generally, something tangible, something you can hold in your hand, such as:

Insight deliverables are, generally, something tangible, something you can hold in your hand, such as:

ο learning objectives for a training program

ο the results of a competitive assessment

ο forecasts

ο specifications

ο validated assumptions

![]() Planning deliverables include the wide range of outcomes necessary for producing a conceptual or implementable plan, such as:

Planning deliverables include the wide range of outcomes necessary for producing a conceptual or implementable plan, such as:

ο arrangements made to conduct a training program

ο resource requirements

ο implementation timetables

![]() Implementation deliverables are something you can readily witness or observe, often capable of being measured and evaluated, such as:

Implementation deliverables are something you can readily witness or observe, often capable of being measured and evaluated, such as:

ο a program for training consultants

ο trained consultants (or sales forces, etc.)

ο improved targeting efforts on the part of a sales force

Are the Deliverables and Desired Result(s) Aligned with the Benefits? (Logics Worksheet, Cells 5 and 6)

As the simplified baseline logic illustrates (Figure 3.6), benefits come from two elements: deliverables and desired result(s). Accordingly, benefits are the good things that accrue (1) while the project’s objectives are being achieved (that is, those generated from deliverables) and (2) after the project’s objectives have been achieved (that is, the direct result of achieved objectives).

Benefits flow from my desired result because once you have moved me from a less desirable state to a more desirable state, I am better off than I was before. Benefits flow from deliverables because at each juncture along the transition from one state to another, I am relatively better off than I was before. As an example, let’s consider the story about “your” daughter. Assume that (1) she is attending undergraduate school at home, where she has many friends, (2) she has a close relationship with you and would want to come home from graduate school during major holidays and school vacations, and (3) she has a medical condition that could require unexpected hospitalization. Clearly, a deliverable such as “cost and convenience of traveling home” would be important, and its existence would provide you and your daughter with many benefits in terms of knowledge, comfort, and the ability to plan appropriately. Every deliverable is beneficial. Each deliverable should generate at least one benefit. If it doesn’t, then why are you even including it in your project?

Benefits are usually of three kinds:

![]() An insight benefit is usually something you hold in your head—for example, understanding, awareness, or knowledge (unlike an insight deliverable, which you can often hold in your hand). An example is the benefit derived from a forecast (a deliverable) that allows me and my organization to determine the likely revenue for a new drug and, therefore, the level of investment justified for launching that pharmaceutical product.

An insight benefit is usually something you hold in your head—for example, understanding, awareness, or knowledge (unlike an insight deliverable, which you can often hold in your hand). An example is the benefit derived from a forecast (a deliverable) that allows me and my organization to determine the likely revenue for a new drug and, therefore, the level of investment justified for launching that pharmaceutical product.

FIGURE 3.6 The simplified baseline logic

![]() A planning benefit (which also can often involve understanding or knowledge) can be:

A planning benefit (which also can often involve understanding or knowledge) can be:

ο An enabler for achieving a result—for example, “a road map for . . . ,” “an understanding of the magnitude of the effort,” “direction . . . ,” and so on. An example is the benefit of a revised call and targeting plan that allows me to know how much of the sales force needs to be deployed when and where.

ο Group buy-in—for example, “commitment,” “consensus,” or “confirmation.” An example is the benefit from training my sales force in the value of a revised customer-targeting program, so they both believe in it and execute it fully, rather than continuing to call on their existing and familiar contacts.

![]() An implementation benefit often is a measurable or tangible result—for example, a change in my organization’s business performance—and should be quantified whenever possible to help determine the basis for calculating return on consulting investment (ROCI). Examples include the ROCI achieved from a higher value on a drug for which I am executing a licensing deal; a more productive sales force; a greater return on promotional spend through better target marketing.

An implementation benefit often is a measurable or tangible result—for example, a change in my organization’s business performance—and should be quantified whenever possible to help determine the basis for calculating return on consulting investment (ROCI). Examples include the ROCI achieved from a higher value on a drug for which I am executing a licensing deal; a more productive sales force; a greater return on promotional spend through better target marketing.

In general, deliverables are more specific than benefits (implementation benefits sometimes excepted), but that doesn’t mean they are more important. In fact, deliverables are only instrumental. A list of specifications, such as in the graduate school example, is only useful and relevant if it leads to something more important, like knowledge or understanding, which is ultimately what I pay you for.

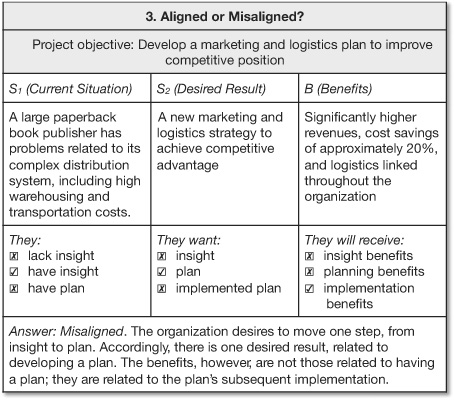

In proposal after proposal that I have read (and, possibly, in some of the proposals you have written), the benefits are not aligned with the deliverables and desired result, as is the case with the following two examples.

For the first example, assume that I know that my customer service levels are too low to be competitive. That’s my current situation, my S1 state. What I have is insight; I know I have a problem. What I don’t have, but desire, is a plan for acting on that insight.

Therefore, my desired result, S2, is a plan for improving customer service, and your objective would be related to developing that improvement plan. The benefits to me in this effort would not be those advantages accruing from achieving improved levels of customer service. My desired result, at least for now, at the completion of this project, is not improved customer service but a plan to improve it. Therefore, the benefits to me of your support are those advantages related to my having the plan you propose to develop. Those benefits, of course, could be considerable. At the beginning of your involvement, I had a problem that I didn’t know how to fix. At the end of your efforts, I have a plan for fixing it. I now know how to improve the levels of my organization’s customer service.

In proposal situation after proposal situation, I have asked for a plan (e.g., to improve customer service) only to get a proposal filled with benefits related to improved customer service. These are benefits I’d receive only after the plan was implemented. In specifying implementation benefits from a Planning Project, the consultants placed themselves in considerable jeopardy. Because the proposal is a contract, I could have made them deliver those “promised” implementation benefits by requiring an implementation phase at a cost to them of several hundred thousand dollars or more.

Now, as we’ll see in the next chapter, your proposal could—and probably should—discuss the benefits related to subsequent implementation, especially if you can estimate those benefits. For example: “Subsequent to implementation, we expect your customer service to improve by X percent, thereby enabling you to do good things 1, 2, and 3.” But if those implementation benefits are the only ones you discuss, you are missing significant opportunities to persuade me of the advantages of your developing the plan itself. These advantages—learning what we need to do better or faster, assessing our current organization’s capabilities, selling the capital requirements to corporate management, evaluating our probability of success, training our people—provide me and my organization with significant benefits. With this plan, we can compare our options and decide to implement, wait, or whatever else may be appropriate given our resources and all the other plans we are considering in areas beyond the one you are studying.

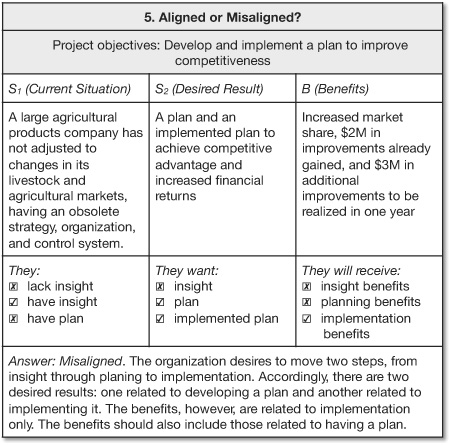

Here’s a second example of misalignment. Assume again that I know my customer service is less effective than is desirable. Again, what I have is insight. In this case, however, assume that what I desire is not only a plan but also an implemented plan that actually improves my customer service.

Therefore, your project’s desired results and objectives (note the plural) need to express both your developing that plan and implementing it. Likewise, the benefits you express need to be those related both to my having the kind of plan you develop and to having that plan implemented. Again and again, in proposal situations like this one, the proposals indicate only the benefits of having the plan implemented. What they fail to do, or at least to communicate to me, is that the quality of the implementation often depends on the quality of the plan. Therefore, they miss important opportunities to persuade. They fail to indicate the benefits aligned with the first objective: developing the plan itself.

To test your understanding of the alignment between the desired result(s) and the benefits, I’d like you to evaluate the six situations found in Figures 3.7 through 3.12. Each table takes information from a different proposal I’ve had presented to me. Each table summarizes the current situation, the desired result(s), and the benefits as they were defined in the proposal. In the S1 column, I’ve included the three possible current situations; in the S2 column, the three possible desired results; in the Benefits column, the three kinds of benefits: insight, planning, and implementation. The checked boxes in each column indicate which current situation, desired result(s), and benefits are being described. By comparing those boxes, you should be able to detect misalignments. The bottom of each table explains whether the desired results and benefits are aligned or misaligned.

Are the Benefits Aligned with the Effects/Lack of Benefits? (Logics Worksheet, Cells 2 and 6)

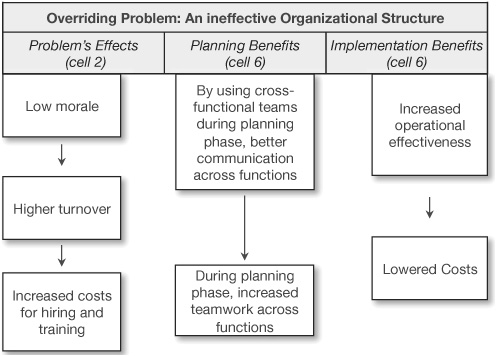

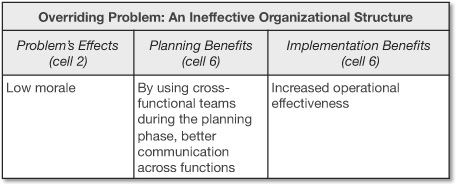

By answering this question, you will not only assure alignment; you will also be able to generate additional possible benefits and additional possible effects that characterize and broaden your and my understanding of my current situation. The process of aligning benefits with the effects/lack of benefits is suggested by the graphic in the Logic Worksheet’s second and sixth cells and in Figure 3.13, on page 40.

Here’s an example of how you can use this process. Assume that yours is a proactive lead with my organization. That is, you haven’t received an RFP (request for proposal) from us, and you haven’t been asked in any way to submit a proposal: You have initiated the lead.

FIGURE 3.7 Aligned or misaligned?

FIGURE 3.8 Aligned or misaligned?

FIGURE 3.9 Aligned or misaligned?

FIGURE 3.10 Aligned or misaligned?

FIGURE 3.11 Aligned or misaligned?

FIGURE 3.12 Aligned or misaligned?

Step 1: List

Along with your team:

![]() You used the Logics Worksheet to strategize what my overriding problem might be, what effects it might be having on my firm, and what benefits could accrue from your efforts.

You used the Logics Worksheet to strategize what my overriding problem might be, what effects it might be having on my firm, and what benefits could accrue from your efforts.

![]() You listed that information (which I’ve displayed in Figure 3.14).

You listed that information (which I’ve displayed in Figure 3.14).

![]() You briefly discussed that information during a phone call with me to arrange a meeting so that we could discuss the “lead” further.

You briefly discussed that information during a phone call with me to arrange a meeting so that we could discuss the “lead” further.

As in most proactive leads, you are the triggering event, in this case making me conscious that I might have an overriding problem and that a Planning and Implementation Project might be needed.

FIGURE 3.13 The process for aligning effects and benefits

FIGURE 3.14 The “list” step of aligning effects and benefits

Step 2: Expand

After listing the effects and benefits above, you can use the power of the baseline logic to increase your depth of understanding of my probable situation by expanding the listed items. To do so, you keep asking yourself, “What is the effect of this effect?” “What is the effect of that new effect?” “What is the effect of this benefit?” “What does or might it lead to?” As you examine column 1, you decide that lowered morale could lead to higher turnover, which could lead to increased costs related to hiring and training. As you examine column 2, you decide that a plan using cross-functional teams could lead to increased teamwork across the organization. As you examine column 3, you decide that increased operational effectiveness and customer responsiveness could lead to lowered costs. Your expanded list looks like Figure 3.15.

Step 3: Align

Typically, the “expand” step takes you down the columns, as you continually ask, “What is the effect of this effect?” and “What benefit would accrue from this benefit?” For the “align” step, you move across the columns, in both directions. In moving left to right: For every effect in column 1, you want to include a related benefit in column 2 and/or column 3. In moving right to left: For every benefit in column 2 or 3, you want to include an effect in column 1.

FIGURE 3.15 The “expand” step of aligning effects and benefits

Let’s move left to right, first by aligning effects with benefits and then by aligning planning benefits with implementation benefits. If your project involves implementation, many of your potential implementation benefits are the converse of the overriding problem’s effects. If an overriding problem’s effect is decreasing market share, once the overriding problem is solved, as it would be in an Implementation Project, a likely implementation benefit would be maintained or increased market share (or at least the deceleration of share loss). At the top of Figure 3.16, note the two (horizontal) alignments between effects and implementation benefits as well as the two alignments between planning benefits and implementation benefits.

Now let’s move right to left, identifying planning and/or implementation benefits that are not aligned with effects. If subsequent to implementation, my firm has increased teamwork across functions, it’s possible that my current situation is characterized by less teamwork. If subsequent to implementation, my firm has more shared knowledge because of fewer functional silos, it’s possible that my current situation is characterized by less shared knowledge because of larger or more numerous functional silos. On the bottom of Figure 3.16, note these two alignments (dashed arrows), between implementation benefits and effects.

FIGURE 3.16 The “align” step of aligning effects and benefits

When aligning right to left, from benefits to effects, you usually do not generate new effects of the overriding problem. You generate what I call “lack of benefits.” They are not the primary reason why I’m thinking about engaging you, but they might be important aspects of my current situation, which involves more than just a problem and its effects. It also includes a lack of benefits. That is, I want to reach S2 because being there is inherently better, and I do not want to be at S1 because certain aspects of that situation are not beneficial. The current situation is undesirable not only because it includes an unaddressed or unsolved problem and its effects but also because it lacks benefits (such as, in the ABC case, consensus among the management team).

By checking the alignment of the overriding problem’s effects and the benefits, you can generate a good deal of additional content to be used in your situation and benefits slots. You can use the alignment as a powerful discovery process to deepen your understanding of my problem or opportunity and the benefits that would accrue from your helping me solve or realize it. Just as important, the benefits you decide to include in your proposal will look all the more beneficial if they are compared to my current lack of benefits, as demonstrated in Figure 3.17.

My guess is that you could have generated Figure 3.16’s information in about five minutes. In 15 minutes, you probably could fill several pages of effects and benefits, identifying them through the process of alignment. Nevertheless, nearly every one of those effects and benefits would need to be red flagged. In the phone call to arrange our meeting, you mentioned four items that I appeared to ratify. Everything else is your conjecture, and even those four items might be as well. My focus during our phone conversation was on scheduling the meeting. I might have been “nodding my head” at everything else. In a brief phone call, I certainly could not have thought deeply about your four items. They might just have been interesting enough for me to accept a meeting.

So everything should be red flagged, and that’s a good thing. Now you have talking points for our meeting. You have points for discussion, items to be confirmed or rejected. During our meeting, you will have caused me to define more precisely my current situation and the potential benefits from improving it. You will have added value, a “richness” of logical thinking, in the business-development process, even though before the meeting I had no idea that you had already begun to “write” your proposal.

One last point about alignment: Once you’ve aligned effects and benefits, you are not finished with all the alignments we have discussed. Unless you wish to throw logic to the wind, there is no end to the iterative alignment process, on the Logics Worksheet and in your head, until your final proposal has been submitted. Every element of the Logics Worksheet is logically related with every other element. Therefore, when you change one element, that change cascades through the entire system (like altering a cell in a spreadsheet), potentially affecting every other element and providing you (and potentially me) new points of view through informed discussion. That discussion adds value, building our relationship and demonstrating your qualifications long before the proposal might be due.

You should be realigning constantly, after every discussion with me and my team and after every discussion between you and your team—whenever new information must be added to the Logics Worksheet. As a result of this iterative process, you may well differentiate yourself from your competition because it shows me you really are thinking about me and my organization’s situation and needs.

FIGURE 3.17 When compared to the lack of benefits, benefits will look even more beneficial.

The Baseline Logic and Your Value Proposition

In using the baseline logic, you are identifying and aligning key elements of your value proposition. As you probably know, your value proposition is a concise statement of your offering. As such, it contains at least five elements:

1. Where I am now: S1, my current situation

2. Where I want to be: my desired result(s), S2, as expressed by your project’s objective(s)

3. When I will get there (the duration of your project)

4. How much it will cost (your fees and expenses)

5. The benefits (B) of achieving my desired result(s)

The first, second, and fifth of these elements are part of the baseline logic, which you can readily see within the partial value proposition developed for a major airline (Figure 3.18). Clearly, your value proposition is vitally important as you are discussing with me major elements of your proposed project. It is the executive summary of the executive summary of your offering. As such, you can use the elements of the baseline logic in a follow-up email or conversation that can help you confirm that you and I agree on the foundational elements of your potential offering.

The Relationship Among the Generic Structure Slots, the Baseline Logic, and Your Proposed Project

Figure 3.19 provides a high-level summary of what I have been discussing in this and the previous chapter. The foundation of Figure 3.19 is the baseline logic, on top of which are mapped the six generic structure slots, and those slots are sequenced based upon what your project proposes to do:

FIGURE 3.18 The baseline logic and your value proposition

![]() Your project begins by addressing my current situation, S1, which you discuss in your proposal’s situation slot.

Your project begins by addressing my current situation, S1, which you discuss in your proposal’s situation slot.

![]() To move me and my organization to something better, you will employ two inputs—the methodology you will use supported by your qualifications for conducting it. You discuss your methodology in the methods slot, and your qualifications in the qualifications slot.

To move me and my organization to something better, you will employ two inputs—the methodology you will use supported by your qualifications for conducting it. You discuss your methodology in the methods slot, and your qualifications in the qualifications slot.

![]() As a result of those inputs, you will provide me with two major outputs, or outcomes—the achievement of my desired result(s) and the benefits of my having made the transition from one situation to another. You discuss the desired result(s) in the objectives slot. You discuss the benefits in the benefits slot.

As a result of those inputs, you will provide me with two major outputs, or outcomes—the achievement of my desired result(s) and the benefits of my having made the transition from one situation to another. You discuss the desired result(s) in the objectives slot. You discuss the benefits in the benefits slot.

![]() Because the transition takes time and because time costs money, I will pay you for the value you deliver. Your fees are discussed in the costs slot.

Because the transition takes time and because time costs money, I will pay you for the value you deliver. Your fees are discussed in the costs slot.

Chapter 5 will discuss how to construct a logical methodology that will convince me that you can move me from S1 to S2. Before we can turn to methodologies, however, I need to discuss in the next chapter other matters related to objectives. But first, I want to commend you, dear reader, for your perseverance in almost finishing the most difficult chapter in this book. I can assure you that mastering the baseline logic gets far easier with practice and is well worth the effort. You’ll see the “richness” created in aligning the ABC situation in the upcoming work session, where you’ll be able to watch “yourself” fill out a Logics Worksheet for the proposal to the ABC Company.

FIGURE 3.19 The relationship among generic structure slots, baseline logic, and the project

Hang in there: nothing ahead is as difficult as what is now behind you.

CHAPTER 3 REVIEW

Aligning the Baseline Logic

To test the alignment of the elements within the baseline logic:

![]() Be certain that the project objective(s) are aligned with S2.

Be certain that the project objective(s) are aligned with S2.

If S1 → S2 = one step, the project will have one objective.

If S1 → S2 = two steps, the project will have two objectives.

If S1 → S2 = three steps, the project will have three objectives.

![]() Be certain that the potential client’s strategic direction, triggering event, overriding problem, and effects are aligned.

Be certain that the potential client’s strategic direction, triggering event, overriding problem, and effects are aligned.

![]() As shown in Figure 3.1, be certain to align the following:

As shown in Figure 3.1, be certain to align the following:

1. The strategic direction and the triggering event

2. The triggering event and the overriding problem

3. The strategic direction and the overriding problem

4. The overriding problem and its effects/lack of benefits

5. The overriding problem and the overriding question(s)

6. The overriding question(s) and the objective(s)

7. The overriding question(s) and the desired result(s)

8. The objective(s) and the desired result(s)

9. The desired result(s) and the deliverables

10. The desired result(s) and the benefits

11. The deliverables and the benefits

12. The benefits and the effects/lack of benefits

![]() The baseline logic contains three important elements of your value proposition, explaining, in the highest-level summary of your offering, where I am (S1), where I want to be (S2), and how I will benefit by getting and being there (B).

The baseline logic contains three important elements of your value proposition, explaining, in the highest-level summary of your offering, where I am (S1), where I want to be (S2), and how I will benefit by getting and being there (B).

WORK SESSION 2: Aligning the Baseline Logic for the Situation at ABC

You approach the subject of your proposal’s baseline logic with a good deal of care because you know that it provides the foundation for your entire proposal and because you also know that you can use its alignment to help you think more strategically about ABC’s current situation, desired result, and potential benefits. Everything else in your proposal will build on this foundation, and mistakes in thinking and understanding at this point will have dire consequences later. Similarly, good strategy and analytical thinking at this point will pay great dividends later on (for example, making the writing process more efficient and extending even to the project’s execution after you win). To ensure that you construct a solid baseline logic, you use the cells in the Logics Worksheet, shown in Appendix B, or the complete worksheet itself, which can be downloaded from http://mhprofessional.com/freed.

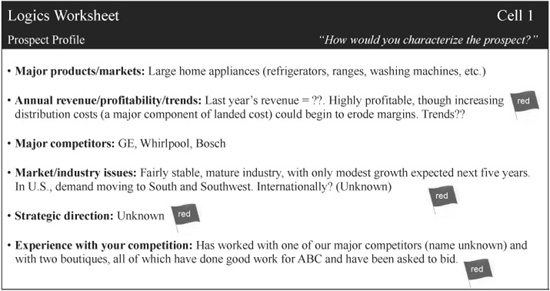

The Logics Worksheet: Cell 1 (See Figure 3.20.)

Most of the information for the “Prospect Profile” you can gather from Gilmore’s notes (see Appendix A for the people involved), but some crucial information is lacking. Although you know that ABC is profitable, you don’t know its last year’s revenue or the trends related to profitability and revenue. These you decide to red flag, using that symbol to mark an uncertainty, vulnerability, gap in information, or anything that you just plain don’t like. In addition, you find nothing in Gilmore’s notes about ABC’s strategic direction. You feel comfortable that the proposed project is very much in line with ABC’s strategic direction, but, it seems to you, the proposal will be stronger if it has some discussion about this topic. Finally, you yourself are unaware of who among your competitors ABC has used before, and nothing in Gilmore’s notes helps you complete this part of Cell 1.

FIGURE 3.20 ABC Logics Worksheet, Cell 1, completed

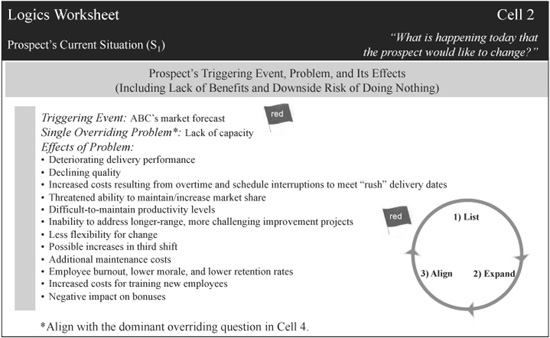

The Logics Worksheet: Cell 2 (See Figure 3.21.)

You know that this cell asks you to define several elements of the “problem bundle”—the overriding problem your project will address or solve, the triggering event or events that brought that problem to the prospect’s consciousness, and the effects of the problem itself. Clearly, the triggering event is ABC’s market forecast, and its overriding problem, at least from ABC’s point of view, is a looming lack of capacity. However, you don’t necessarily see the overriding problem as they do (for the same reasons related to the discussion in Figure 3.22). So you red flag this item, as well as the effects of the problem. Many of these effects (and lack of benefits) were generated by your aligning them with benefits. And while they seem to fit ABC’s situation, many of them are not addressed in Gilmore’s notes. Those that aren’t, you believe, will lead to fruitful follow-up discussions with Ray Armstrong, the president, and his team.

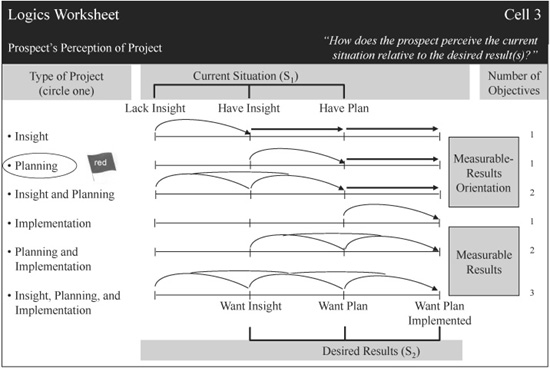

The Logics Worksheets: Cell 3 and Cell 4 (See Figures 3.22 and 3.23.)

The first of these cells asks you to identify the kind of project; the second, ABC’s overriding question(s).

FIGURE 3.21 ABC Logics Worksheet, Cell 2, completed

ABC, you believe, has insight about its current situation—they know they have a production capacity problem, and they desire a plan to address that problem. On the face of it, then, it would appear that you will be proposing a planning study. However, you’re not certain that ABC has the right insight. For example, although they do have a sales forecast—and one in which Marcia Collins, the vice president of marketing, has considerable confidence—you believe that any forecast must be validated, since it provides the basis for all further analysis.

A validated forecast might reveal that ABC doesn’t need quite as much capacity as they now believe or that the timing for implementing additional capacity will be sooner or later than is now anticipated. Furthermore, although Gilmore’s inspection of the main manufacturing facility revealed good workflow and housekeeping and excellent equipment utilization, your experience tells you that various marginal improvements at that facility (and perhaps at the satellite facilities) could provide some additional capacity, perhaps without ABC’s having to invest in bricks and mortar so soon.

Finally, there’s the issue of outsourcing. At present, ABC appears to manufacture most of its components rather than relying on outside suppliers to provide them. Various make-versus-buy scenarios could provide capacity that ABC does not currently enjoy and thus eliminate or certainly delay the need for additional capacity.

FIGURE 3.22 ABC Logics Worksheet, Cell 3, completed

FIGURE 3.23 ABC Logics Worksheet, Cell 4, completed

In short, this might be a classic insight and planning study. Like many such combination studies, this one could involve phasing, a possible “go/no go” decision point at the end of the insight piece. That is, the first phase of the study might supply ABC with the insight it needs to determine whether it indeed requires additional capacity as soon as it believes it does (and, if so, how much by when).

On the other hand, you don’t believe that you could sell an insight and planning study to ABC or that ABC senses a decision point. All the buyers seem to believe that additional capacity is necessary, although the amount and timing are uncertain. More specifically, Collins would certainly object to an insight study and, depending on her influence, so might others. So you decide to characterize this opportunity as a planning study. It will certainly have an insight element, in the form of a deliverable validating Collins’s forecast, but it will have only one objective: to develop a plan. Therefore, because there will be no decision point after validating the forecast, you decide to call the project what in your mind ABC believes it to be: a study to develop a plan for increasing production capacity. You do, however, assign a red flag indicating a potential disagreement between how you and ABC view the kind of study this should be. Because of this uncertainty, you also need to red flag Cell 4 (Figure 3.23), since in your mind, the study could very well have both an insight and a planning question.

Because you have now circled “Planning” in Cell 3, you know that you will use the Planning column in Cells 4, 5, and 6. That is, you are continuing to complete the cells from ABC’s point of view, red flagging whenever your point of view differs. From ABC’s point of view, this is a planning study. Consequently, you will use the Planning (rather than the Insight or Implementation) column to enter information related to the overriding question, desired result, deliverables, and benefits.

The Logics Worksheet: Cell 5 (See Figure 3.24.)

This cell asks you to specify the desired result or results to be produced by your project and the deliverables that, taken together, will produce them. The desired result, you know, should be a simple rephrasing of the overriding question, and it should express your project’s objective, which, in this case, would be to develop a plan to increase capacity to meet the market forecast. Because the overriding question is flagged, the desired result also must be flagged.

You know that the deliverables are outcomes produced during the project. They are the key outputs that will move ABC from its current situation to its desired result. Although you are comfortable with most of the deliverables you have identified, you are concerned about two matters. First, all the deliverables should be, by definition, red flagged since the desired result also is flagged. If the overriding question and desired result changed, the deliverables would change as well. Second, two of the deliverables are particularly worrisome. The first, the “validated market forecast,” could anger Collins, who developed the forecast and appears to be confident of its validity and reliability. The phrasing, you realize, reflects your point of view rather than Collins’s.

FIGURE 3.24 ABC Logics Worksheet, Cell 5, completed

You believe, of course, it’s essential to validate the forecast; the whole study could depend on it. Perhaps what you really want to say is “updated market forecast to reflect current market conditions.” The fifth deliverable, “make versus buy options,” is also troublesome because it’s not really aligned with ABC’s understanding of capacity, which tends to focus on bricks and mortar and on additional equipment.

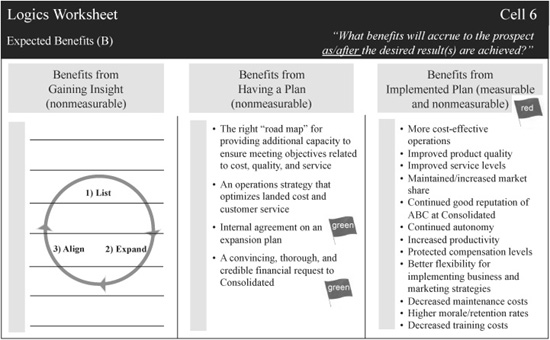

The Logics Worksheet: Cell 6 (See Figure 3.25.)

You know that this cell allows you to align many elements of the baseline logic and, while doing so, to identify additional benefits and effects that could very well deepen your understanding of ABC’s current situation and the advantages of changing it. After considering the “list/expand/align” procedure in Cells 2 and 6 (and the material in the next chapter), you know the following:

![]() You should complete the benefits in the Planning column.

You should complete the benefits in the Planning column.

![]() To indicate to ABC the likely benefits of implementing the plan you will develop, you should indicate the likely benefits that will accrue subsequent to implementation. This “measurable-results orientation” strategy not only will provide ABC a good sense of the “end game,” it also could position you well to be chosen to conduct the Implementation Project.

To indicate to ABC the likely benefits of implementing the plan you will develop, you should indicate the likely benefits that will accrue subsequent to implementation. This “measurable-results orientation” strategy not only will provide ABC a good sense of the “end game,” it also could position you well to be chosen to conduct the Implementation Project.

![]() Benefits flow from the achievement of the desired result and from the deliverables produced along the way. Therefore, you should attempt to identify one or more benefits from the stated desired result as well as from each deliverables in Cell 5.

Benefits flow from the achievement of the desired result and from the deliverables produced along the way. Therefore, you should attempt to identify one or more benefits from the stated desired result as well as from each deliverables in Cell 5.

![]() For each benefit you list, you should then expand by asking yourself, “What likely benefits will accrue if this listed benefit occurs.”

For each benefit you list, you should then expand by asking yourself, “What likely benefits will accrue if this listed benefit occurs.”

![]() You should align each expanded benefit by asking the following questions:

You should align each expanded benefit by asking the following questions:

ο Is there at least one deliverable that will generate this benefit? If not, you should add one and consider whether this new deliverable is aligned with the desired result.

ο Is there an effect (or a lack of benefits) aligned with this benefit? If not, you should add at least one in Cell 2.

![]() After completing the alignment process, you should red flag any newly generated benefit, deliverable, effect, or lack of benefit that has not been discussed with ABC and/or that appears “out of scope.”

After completing the alignment process, you should red flag any newly generated benefit, deliverable, effect, or lack of benefit that has not been discussed with ABC and/or that appears “out of scope.”

When you are finished, your efforts look like those in Figure 3.25, with most of the implementation benefits red flagged and two of the planning benefits green flagged, a symbol you are using to indicate a particular strength. These green-flagged items, you believe, will be particularly persuasive to ABC, given the situation described to you by Gilmore. You realize that you could go on ad infinitum generating additional effects and benefits. However, you decide for now that you have enough to show to Gilmore, who can confirm what you have or seek additional confirmation from the major players at ABC. Just as important, you feel confident that the foundation to your proposal is indeed sound and logical—and much more extensive than you had realized. You have used the alignment process to develop ideas that could help ABC better understand their own situation as well as differentiate you from your competitors.

FIGURE 3.25 ABC Logics Worksheet, Cell 6, completed

Your Value Proposition

After all this hard work, you find that your value proposition practically writes itself. Taking information from the worksheets related to the current situation, the desired results, and the benefits, you write the following in less than five minutes, which also includes the overriding problem’s effects:

ABC’s market forecast indicates that you will exceed manufacturing capacity in as little as two years, potentially leading to declining quality, deteriorating delivery performance, and threatened market share. Accordingly, Paramount Consulting will develop a thorough and comprehensive plan to increase capacity, providing a solid “road map” ensuring that you meet your objectives related to cost, quality, and service. Subsequent to implementation, we expect that your operations will be more cost-effective and that your product quality and service levels will improve, significantly helping you maintain your standing as Consolidated Industries’ premier division.

This paragraph, you realize, will make a solid contribution to the proposal’s introduction. Given what you know of Gilmore’s business-development process, you expect that he will e-mail the value proposition to each of ABC’s buyers, well before the proposal is due, with the aim of validating the triggering event, overriding problem, effects, objective, and benefits.