Chapter 10. Advanced Form Techniques

IN THIS CHAPTER

- Why This Chapter Is Important

- What Are the Form Events, and When Do You Use Them?

- What Are the Section and Control Events, and When Do You Use Them?

- Referring to

Me - What Types of Forms Can I Create, and When Are They Appropriate?

- Using Built-In Dialog Boxes

- Taking Advantage of Built-In, Form-Filtering Features

- Including Objects from Other Applications: Linking Versus Embedding

- Using

OpenArgs - Switching a Form’s

RecordSource - Learning Power Combo Box and List Box Techniques

- Learning Power Subform Techniques

- Using Automatic Error Checking

- Viewing Object Dependencies

- Using AutoCorrect Options

- Propagating Field Properties

- Synchronizing a Form with Its Underlying Recordset

- Creating

CustomProperties and Methods - Practical Examples: Applying Advanced Techniques to Your Application

Why This Chapter Is Important

Given Access’s graphical environment, your development efforts are often centered on forms. Therefore, you must understand all the Form and Control events and know which event you should code to perform each task. You should also know what types of forms are available and how you can get the look and behavior you want in them.

Often, you won’t need to design your own form because you can make use of one of the built-in dialog boxes that are part of the Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) language. Whatever types of forms you create, you should take advantage of all the tricks and tips of the trade covered throughout this chapter.

What Are the Form Events, and When Do You Use Them?

Microsoft Access traps (responds to) for over 30 Form events (excluding those specifically related to pivot tables), each of which has a distinct purpose. Access also traps events for Form sections and controls. The following sections cover the Form events and when you should use them.

Current

A form’s Current event is one of the more commonly coded events. It happens each time focus moves from one record to another. The Current event is a great place to put code that you want to execute whenever the user displays a record. For example, you might want the cursor to move to the contact first name control if the user moves to a new client. The following code is placed in the Current event of the frmClients form that’s part of the hypothetical time and billing application that you’ve been building in the previous chapters:

This code moves focus to the txtContactFirstName control if the txtClientID control of the record that the user is moving to happens to be Null; this happens if the user is adding a new record.

BeforeInsert

The BeforeInsert event occurs when the first character is typed in a new record but before the new record is actually created. If the user is typing in a text or combo box, the BeforeInsert event occurs even before the Change event of the text or combo box. The frmProjects form of the time and billing application has an example of a practical use of the BeforeInsert event:

The frmProjects form is always called from the frmClients form. The BeforeInsert event of frmProjects sets the value of the txtClientID text box equal to the value of the txtClientID text box on frmClients.

AfterInsert

The AfterInsert event occurs after the record has actually been inserted. You can use it to requery a recordset after a new record is added.

Note

Here’s the order of form events when a user begins to type data into a new record:

BeforeInsert->BeforeUpdate->AfterUpdate->AfterInsert

The BeforeInsert event occurs when the user types the first character, the BeforeUpdate event happens when the user updates the record, the AfterUpdate event takes place when the record is updated, and the AfterInsert event occurs when the record that’s being updated is a new record.

BeforeUpdate

The BeforeUpdate event runs before a record is updated. It occurs when the user tries to move to a different record (even a record on a subform) or when the Records, Save Record command is executed. You can use the BeforeUpdate event to cancel the update process when you want to perform complex validations. When a user adds a record, the BeforeUpdate event occurs after the BeforeInsert event. The frmClients form in the CHAP10EX sample database provides an example of using a BeforeUpdate event:

This code determines whether the first name, last name, company name, or phone number contains Null. If any of these fields contains Null, the code displays a message, and the Cancel parameter is set to True, canceling the update process. As a convenience to the user, focus is placed in the txtFirstName control.

AfterUpdate

The AfterUpdate event occurs after the changed data in a record is updated. You might use this event to requery combo boxes on related forms or perhaps to log record changes. Here’s an example:

![]()

This code requeries the cboSelectProduct combo box after the user updates the current record.

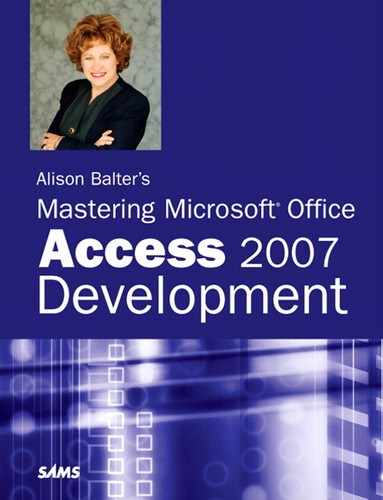

Dirty

The Dirty event occurs when the contents of the form, or of the text portion of a combo box, change. It also occurs when you programmatically change the Text property of a control. Here’s an example:

This code, located in the frmClients form of the time and billing application, calls FlipEnabled to flip the command buttons on the form. This has the effect of enabling the Save and Cancel command buttons and disabling the other command buttons on the form. The code also removes the navigation buttons, prohibiting the user from moving to other records while the data is in a “dirty” state.

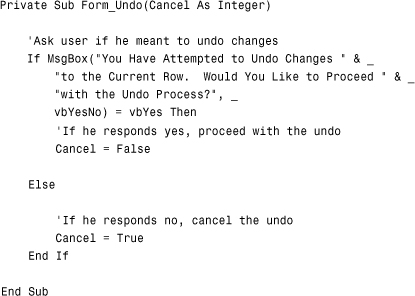

Undo

The Undo event executes before changes to a row are undone. The Undo event initiates when the user clicks the Undo button on the Quick Access toolbar, presses the Esc key, or executes code that attempts to undo changes to the row. If you cancel the Undo event, the changes to the row are not undone. Here’s an example:

This code, located in the frmProjects form of the time and billing application, displays a message to the user, asking him if he really wants to undo his changes. If he responds Yes, the Undo process proceeds. If he responds No, the Undo process is canceled.

Delete

The Delete event occurs when a user tries to delete a record but before the record is removed from the table. This is a great way to place code that allows deleting a record only under certain circumstances. If the Delete event is canceled, the BeforeDelConfirm and AfterDelConfirm events (covered next) never execute, and the record is never deleted.

Tip

When the user deletes multiple records, the Delete event happens after each record is deleted. This allows you to evaluate a condition for each record and decide whether to delete each record.

BeforeDelConfirm

The BeforeDelConfirm event takes place after the Delete event but before the Delete Confirm dialog box is displayed. If you cancel the BeforeDelConfirm event, the record being deleted is restored from the delete buffer, and the Delete Confirm dialog box is never displayed.

AfterDelConfirm

The AfterDelConfirm event occurs after the record is deleted or when the deletion is canceled. If the code does not cancel the BeforeDelConfirm event, the AfterDelConfirm event takes place after Access displays the Confirmation dialog box.

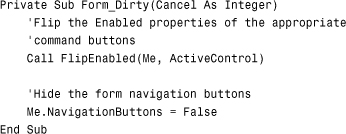

Open

The Open event occurs when a form is opened but before the first record is displayed. With this event, you can control exactly what happens when the form first opens. The Open event of the time and billing application’s frmProjects form looks like this:

This code checks to make sure the frmClients form is loaded. If it isn’t, it displays a message box and sets the Cancel parameter to True, which prohibits the form from loading.

Load

The Load event happens when a form opens, and the first record is displayed; it occurs after the Open event. A form’s Open event can cancel the loading of a form, but the Load event can’t. The following routine is placed in the Load event of the time and billing application’s frmExpenseCodes form:

This routine looks at the string that’s passed as an opening argument to the form. If the OpenArgs string is not Null, and the form is opened in Data Entry mode, the txtExpenseCode text box is set equal to the opening argument. In essence, this code allows the form to be used for two purposes. If the user opens the form from the database container, no special processing occurs. On the other hand, if the user opens the form from the fsubTimeCardsExpenses subform, the form is opened in Data Entry mode, and the expense code that the user specified is placed in the txtExpenseCode text box.

Resize

The Resize event takes place when a form is opened or whenever the form’s size changes.

Unload

The Unload event happens when a form is closed but before Access removes the form from the screen. It’s triggered when the user closes the form, quits the application by choosing End Task from the task list or quits Windows, or when your code closes the form. You can place code that makes sure it’s okay to unload the form in the Unload event, and you can also use the Unload event to place any code you want executed whenever the form is unloaded. Here’s an example:

This code is in the Unload event of the frmClients form from the time and billing application. It checks whether the Save button is enabled. If it is, the form is in a dirty state. The user is prompted as to whether she wants to save changes to the record. If she responds yes, the code saves the data, and the form is unloaded. If she responds no, the code cancels changes to the record, and the form is unloaded. Finally, if she opts to cancel, the value of the Cancel parameter is set to False, and the form is not unloaded.

Close

The Close event occurs after the Unload event, when a form is closed and removed from the screen. Remember, you can cancel the Unload event but not the Close event.

The following code is located in the Close event of the frmClients form that’s part of the time and billing database:

When the frmClients form is closed, the code tests whether the frmProjects form is open. If it is, the code closes it.

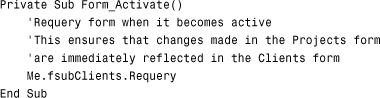

Activate

The Activate event takes place when the form gets focus and becomes the active window. It’s triggered when the form opens, when a user clicks on the form or one of its controls, and when the SetFocus method is applied by using VBA code. The following code, found in the Activate event of the time and billing application’s frmClients form, requeries the fsubClients subform whenever the frmClients main form activates:

Deactivate

The Deactivate event occurs when the form loses focus, which happens when a table, query, form, report, macro, module, or the Navigation Pane becomes active. However, the Deactivate event isn’t triggered when a dialog box, pop-up form, or another application becomes active.

GotFocus

The GotFocus event happens when a form gets focus, but only if there are no visible, enabled controls on the form. This event is rarely used for a form.

LostFocus

The LostFocus event occurs when a form loses focus, but only if there are no visible, enabled controls on the form. This event, too, is rarely used for a form.

Click

The Click event takes place when the user clicks on a blank area of the form, on a disabled control on the form, or on the form’s record selector.

DblClick

The DblClick event happens when the user double-clicks on a blank area of the form, on a disabled control on the form, or on the form’s record selector.

MouseDown

The MouseDown event occurs when the user clicks on a blank area of the form, on a disabled control on the form, or on the form’s record selector. However, it happens before the Click event fires. You can use it to determine which mouse button was pressed.

MouseMove

The MouseMove event takes place when the user moves the mouse over a blank area of the form, over a disabled control on the form, or over the form’s record selector. It’s generated continuously as the mouse pointer moves over the form. The MouseMove event occurs before the Click event fires.

MouseUp

The MouseUp event occurs when the user releases the mouse button. Like the MouseDown event, it happens before the Click event fires. You can use the MouseUp event to determine which mouse button was pressed.

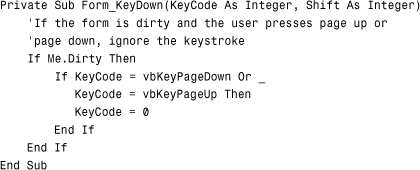

KeyDown

The KeyDown event happens if there are no controls on the form or if the form’s KeyPreview property is set to Yes. If the latter condition is true, all keyboard events are previewed by the form and occur for the control that has focus. If the user presses and holds down a key, the KeyDown event occurs repeatedly until the user releases the key. Here’s an example:

This code, found in the frmClients form that is part of the time and billing application, tests to see if the form is in a dirty state. If it is, and the user presses the Page Down or Page Up key, Access ignores the keystroke. This prevents the user from moving to other records without first clicking the Save or Cancel command buttons.

KeyUp

Like the KeyDown event, the KeyUp event occurs if there are no controls on the form, or if the form’s KeyPreview property is set to Yes. The KeyUp event takes place only once, though, regardless of how long the user presses the key. You can cancel the keystroke by setting KeyCode to 0.

KeyPress

The KeyPress event occurs when the user presses and releases a key or key combination that corresponds to an ANSI code. It takes place if there are no controls on the form, or if the form’s KeyPreview property is set to Yes. You can cancel the keystroke by setting KeyCode to 0.

Error

The Error event triggers whenever an error happens while the user is in the form. Access Database Engine errors are trapped, but Visual Basic errors aren’t. You can use this event to suppress the standard error messages. You must handle Visual Basic errors using standard On Error techniques. Both the Error event and handling Visual Basic errors are covered in Chapter 17, “Error Handling: Preparing for the Inevitable.”

Filter

The Filter event takes place whenever the user selects the Filter By Form or Advanced Filter/Sort options. You can use this event to remove the previous filter, enter default settings for the filter, invoke your own custom filter window, or prevent certain controls from being available in the Filter By Form window. The later section “Taking Advantage of Built-In, Form-Filtering Features” covers filters in detail.

ApplyFilter

The ApplyFilter event occurs when the user selects the Apply Filter/Sort, Filter By Selection, or Remove Filter/Sort options. It also takes place when the user closes the Advanced Filter/Sort window or the Filter By Form window. You can use this event to make sure that the applied filter is correct, to change the form’s display before the filter is applied, or to undo any changes you made when the Filter event occurred. The later section “Taking Advantage of Built-In, Form-Filtering Features” covers filters in detail.

Timer

The Timer event and a form’s TimerInterval property work hand in hand. You can set the TimerInterval property to any value between 0 and 2,147,483,647. The value used determines the frequency, expressed in milliseconds, at which the Timer event will occur. For example, if the TimerInterval property is set to 0, the Timer event will not occur at all; if set to 5000 (5000 milliseconds), the Timer event will occur every five seconds. The following example uses the Timer event to alternate the visibility of a label on the form. This produces a flashing effect. The TimerInterval property can be initially set to any valid value other than 0 but will be reduced by 50 milliseconds each time the code executes. This has the effect of making the control flash faster and faster. The Timer events continue to occur until the TimerInterval property is finally reduced to 0.

Understanding the Sequence of Form Events

One of the mysteries of events is the order in which they occur. One of the best ways to figure this out is to place Debug.Print statements in the events you want to learn about. This technique is covered in Chapter 16, “Debugging: Your Key to Successful Development.” Keep in mind that event order isn’t an exact science; it’s nearly impossible to guess when events will happen in all situations. It’s helpful, though, to understand the basic order in which certain events do take place.

What Happens When a Form Is Opened?

When a user opens a form, the following events occur:

Open->Load->Resize->Activate->Current

After these Form events take place, the Enter and GotFocus events of the first control occur. Remember that the Open event provides the only opportunity to cancel opening the form.

What Happens When a Form Is Closed?

When a user closes a form, the following events take place:

Unload->Deactivate->Close

Before these events occur, the Exit and LostFocus events of the active control trigger.

What Happens When a Form Is Sized?

When a user resizes a form, what happens depends on whether the form is minimized, restored, or maximized. When the form minimizes, here’s what happens:

Resize->Deactivate

When a user restores a minimized form, these events take place:

Activate->Resize

When a user maximizes a form or restores a maximized form, just the Resize event occurs.

What Happens When Focus Shifts from One Form to Another?

When a user moves from one form to another, the Deactivate event occurs for the first form; then the Activate event occurs for the second form. Remember that the Deactivate event doesn’t take place if focus moves to a dialog box, a pop-up form, or another application.

What Happens When Keys Are Pressed?

When a user types a character, and the form’s KeyPreview property is set to True, the following events occur:

KeyDown->KeyPress->Dirty->KeyUp

If you trap the KeyDown event and set the KeyCode to 0, the remaining events never happen. The KeyPress event captures only ANSI keystrokes. This event is the easiest to deal with. However, you must handle the KeyDown and KeyUp events when you need to trap for non-ANSI characters, such as Shift, Alt, and Ctrl.

What Happens When Mouse Actions Take Place?

When a user clicks the mouse button, the following events occur:

MouseDown->MouseUp->Click

What Are the Section and Control Events, and When Do You Use Them?

Sections have only five events: Click, DblClick, MouseDown, MouseMove, and MouseUp. These events rarely play significant roles in your application.

Each control type has its own set of events to which it responds. Many events are common to most controls, but others are specific to certain controls. Furthermore, some controls respond to very few events. The following sections cover most of the Control events and the controls they apply to.

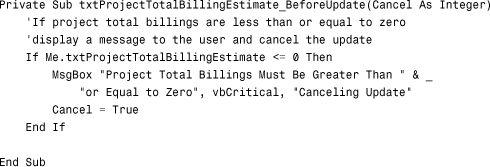

BeforeUpdate

The BeforeUpdate event applies to text boxes, option groups, combo boxes, list boxes, and bound object frames. It occurs before changed data in the control updates. You can find the following code example in the BeforeUpdate event of the txtProjectTotalBillingEstimate control on the frmProjects form in the sample database:

This code tests whether the value of the CustomerID control is less than or equal to zero. If it is, the code displays a message box, and the Update event is canceled.

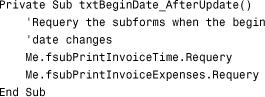

AfterUpdate

The AfterUpdate event applies to text boxes, option groups, combo boxes, list boxes, and bound object frames. It occurs after changed data in the control updates. The following code example is from the AfterUpdate event of the txtBeginDate control on the frmPrintInvoice form found in the time and billing database:

This code requeries both the fsubPrintInvoiceTime subform and the fsubPrintInvoiceExpenses subform when the txtBeginDate control updates. This ensures that the subforms display the time and expenses appropriate for the selected date range.

Updated

The Updated event applies to a bound object frame only. It occurs when the object linking and embedding (OLE) object’s data is modified.

Change

The Change event applies to text and combo boxes and takes place when data in the control changes. For a text box, this event occurs when the user types a character; for a combo box, it happens when a user types a character or selects a value from the list. You use this event when you want to trap for something happening on a character-by-character basis.

NotInList

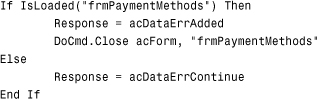

The NotInList event applies only to a combo box and happens when a user enters a value in the text box portion of the combo box that’s not in the combo box list. By using this event, you can allow the user to add a new value to the combo box list. For this event to be triggered, the LimitToList property must be set to Yes. Here’s an example from the time and billing application’s frmPayments form:

This code executes when a user enters a payment method that’s not in the cboPaymentMethodID combo box. It asks the user if he wants to add the entry. If he responds yes, the frmPaymentMethods form displays. Otherwise, the user must select another entry from the combo box. The NotInList event is covered in more detail later in the “Handling the NotInList Event” section.

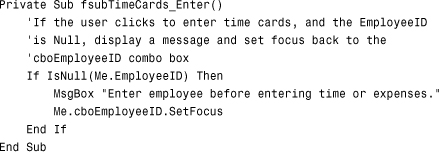

Enter

The Enter event applies to text boxes, option groups, combo boxes, list boxes, command buttons, object frames, and subforms. It occurs before a control gets focus from another control on the same form and before the GotFocus event. Here’s an example from the time and billing application’s frmTimeCards form:

When the user moves into the fsubTimeCards subform control, its Enter event tests whether the EmployeeID has been entered on the main form. If it hasn’t, a message box displays, and focus is moved to the cboEmployeeID control on the main form.

Exit

The Exit event applies to text boxes, option groups, combo boxes, list boxes, command buttons, object frames, and subforms. It occurs just before the LostFocus event.

GotFocus

The GotFocus event applies to text boxes, toggle buttons, option buttons, check boxes, combo boxes, list boxes, and command buttons. It takes place when focus moves to a control in response to a user action or when the SetFocus, SelectObject, GoToRecord, GoToControl, or GoToPage method is issued in code. Controls can get focus only if they’re visible and enabled.

LostFocus

The LostFocus event applies to text boxes, toggle buttons, option buttons, check boxes, combo boxes, list boxes, and command buttons. It occurs when focus moves away from a control in response to a user action or when your code issues the SetFocus, SelectObject, GoToRecord, GoToControl, or GoToPage methods.

Note

The difference between GotFocus/LostFocus and Enter/Exit lies in when they occur. If focus is lost (moved to another form) or returned to the current form, the control’s GotFocus and LostFocus events are triggered. The Enter and Exit events don’t take place when the form loses or regains focus. Finally, it is important to note that none of these events take place when the user makes menu selections or clicks ribbon buttons.

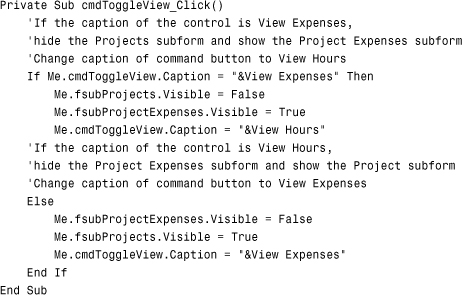

Click

The Click event applies to labels, text boxes, option groups, combo boxes, list boxes, command buttons, and object frames. It occurs when a user presses and then releases a mouse button over a control. Here’s an example from the time and billing application’s frmProjects form:

This code checks the caption of the cmdToggleView command button. If the caption reads "&View Expenses" (with the ampersand indicating a hotkey), the fsubProjects subform is hidden, the fsubProjectExpenses subform is made visible, and the caption of the cmdToggleView command button is modified to read "&View Hours". Otherwise, the fsubProjectExpenses subform is hidden, the fsubProjects subform is made visible, and the caption of the cmdToggleView command button is modified to read "&View Expenses".

Note

The Click event is triggered when the user clicks the mouse over an object, as well as in the following situations:

- When the user presses the spacebar while a command button has focus

- When the user presses the Enter key and a command button’s

Defaultproperty is set toYes - When the user presses the Escape key and a command button’s

Cancelproperty is set toYes - When an accelerator key for a command button is used

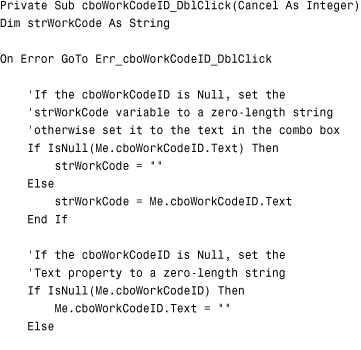

DblClick

The DblClick event applies to labels, text boxes, option groups, combo boxes, list boxes, command buttons, and object frames. It occurs when a user presses and then releases the left mouse button twice over a control. Here’s an example from the time and billing application’s fsubTimeCards form:

In this example, the code evaluates the cboWorkCodeID combo box control to see whether it’s Null. If it is, the text of the combo box is set to a zero-length string. Otherwise, a long integer variable is set equal to the combo box value, and the combo box value is set to Null. The frmWorkCodes form is opened modally. When it’s closed, the cboWorkCodeID combo box is requeried. If the long integer variable doesn’t contain a zero, the combo box value is set equal to the long integer value.

MouseDown

The MouseDown event applies to labels, text boxes, option groups, combo boxes, list boxes, command buttons, and object frames. It takes place when a user presses the mouse button over a control, before the Click event fires.

MouseMove

The MouseMove event applies to labels, text boxes, option groups, combo boxes, list boxes, command buttons, and object frames. It occurs as a user moves the mouse over a control.

MouseUp

The MouseUp event applies to labels, text boxes, option groups, combo boxes, list boxes, command buttons, and object frames. It occurs when a user releases the mouse over a control, before the Click event fires.

KeyDown

The KeyDown event applies to text boxes, toggle buttons, option buttons, check boxes, combo boxes, list boxes, and bound object frames. It happens when a user presses a key while within a control; the event occurs repeatedly until the user releases the key. You can cancel it by setting KeyCode equal to 0.

KeyUp

The KeyUp event applies to text boxes, toggle buttons, option buttons, check boxes, combo boxes, list boxes, and bound object frames. It occurs when a user releases a key within a control. It occurs only once, no matter how long the user presses a key.

KeyPress

The KeyPress event applies to text boxes, toggle buttons, option buttons, check boxes, combo boxes, list boxes, and bound object frames. It occurs when a user presses and releases an ANSI key while the control has focus. You can cancel it by setting KeyCode equal to 0.

Understanding the Sequence of Control Events

Just as Form events take place in a certain sequence when the form is opened, activated, and so on, Control events occur in a specific sequence. You need to understand this sequence to write the event code for a control.

What Happens When Focus Is Moved to or from a Control?

When focus is moved to a control, the following events occur:

Enter->GotFocus

If focus is moving to a control as the form is opened, the Form and Control events take place in the following sequence:

Open(form)->Activate(form)->Current(form)->Enter(control)_

GotFocus(control)

When focus leaves a control, the following events occur:

Exit->LostFocus

When focus leaves the control because the form is closing, the following events happen:

Exit(control)->LostFocus(control)->Unload(form)->Deactivate(form)_

Close(form)

What Happens When the Data in a Control Is Updated?

When you change data in a control and then move focus to another control, the following events occur:

BeforeUpdate->AfterUpdate->Exit->LostFocus

After every character that’s typed in a text or combo box, the following events take place before focus is moved to another control:

KeyDown->KeyPress->Change->KeyUp

For a combo box, if the NotInList event is triggered, it occurs after the KeyUp event.

Referring to Me

The Me keyword is like an implicitly declared variable; it’s available to every procedure in a Form or Report module. Using Me is a great way to write generic code in a form or report. You can change the name of the form or report, and the code will be unaffected. Here’s an example:

Me.RecordSource = "qryProjects"

This code changes the RecordSource property of the current form or report to qryProjects.

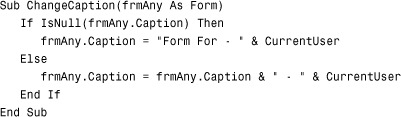

It’s also useful to pass Me (the current form or report) to a generic procedure in a module, as shown in the following example:

Call ChangeCaption(Me)

The ChangeCaption procedure looks like this:

The ChangeCaption procedure in a Code module receives any form as a parameter. It evaluates the caption of the form that was passed to it. If the caption is Null, ChangeCaption sets the caption to "Form For -", concatenated with the user’s name. Otherwise, it takes the existing caption of the form passed to it and appends the user’s name.

What Types of Forms Can I Create, and When Are They Appropriate?

You can design a variety of forms with Microsoft Access. By working with the properties available in Access’s form designer, you can create forms with many different looks and types of functionality. This chapter covers all the major categories of forms, but remember that you can create your own forms. Of course, don’t forget to maintain consistency with the standards for Windows applications.

Single Forms: Viewing One Record at a Time

One of the most common types of forms, the Single form, allows you to view one record at a time. The Single form shown in Figure 10.1, for example, lets the user view one customer record and then move to other records as needed.

Creating a Single form is easy: Simply set the form’s Default View property to Single Form (see Figure 10.2).

Figure 10.2. Setting the form’s Default View property.

Continuous Forms: Viewing Multiple Records at a Time

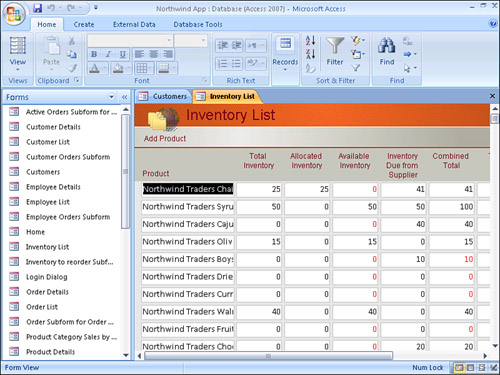

Often, the user wants to be able to view multiple records at a time, which requires creating a Continuous form, like the one shown in Figure 10.3. To do this, just set the Default View property to Continuous Forms.

Figure 10.3. A Continuous form.

A subform is a common use for a Continuous form; generally, you should show multiple records in a subform. The records displayed in the subform are all the records that relate to the record displayed in the main form. Figure 10.4 shows a subform, with its Default View property set to Continuous Forms. The subform shows all the products relating to a specific supplier.

Figure 10.4. A form containing a Continuous subform.

Multipage Forms: Finding Solutions When Everything Doesn’t Fit on One Screen

Scarcity of screen real estate is a never-ending problem, but a multipage form can be a good solution. Figures 10.5 and 10.6 show the two pages of a multipage Employees form. When looking at the form in Design view, you can see a Page Break control placed just at the 3½-inch mark on the form (see Figure 10.7). To insert a Page Break control, select it from the Controls group of the Design tab and then click and drag to place it on the form.

Figure 10.5. The first page of a multipage form.

Figure 10.6. The second page of a multipage form.

Figure 10.7. A multipage form in Design view, showing a Page Break control just before the 3½-inch mark on the form.

When creating a multipage form, remember a few important steps:

- Set the

Default Viewproperty of the form toSingle Form. - Set the

Scrollbarsproperty of the form toNeitherorHorizontal Only. - Set the

Auto Resizeproperty of the form toNo. - Place the Page Break control exactly halfway down the form’s Detail section if you want the form to have two pages. If you want more pages, divide the total height of the Detail section by the number of pages and place Page Break controls at the appropriate positions on the form.

- Size the Form window to fit exactly one page of the form.

Tabbed Forms: Conserving Screen Real Estate

A tabbed form is an alternative to a multipage form. Access 2007 includes a built-in Tab control that allows you to easily group sets of controls. A tabbed form could, for example, show customers on one tab, orders for a selected customer on another tab, and order detail items for the selected order on a third tab.

The form shown in Figure 10.8 uses a Tab control. This form, called Employee Details, is included in the Northwind database. It shows an employee’s general information on one tab and his orders on the second tab. No code is needed to build the example.

Adding a Tab Control and Manipulating Its Pages

To add a Tab control to a form, simply select it from the Controls group on the Design tab and drag and drop it onto the form. By default, two tab pages appear. To add more tabs, right-click the control and select Insert Page. To remove tabs, right-click the page you want to remove and select Delete Page. To change the order of pages, right-click any page and select Page Order.

Adding Controls to the Pages of a Tab Control

You can add controls to each tab just as you would add them directly to the form. Remember to select a tab by clicking it before you add the controls. If you don’t select a specific tab, the controls you add will appear on every tab.

Modifying the Tab Order of Controls

The controls on each page have their own tab order. To modify their tab order, right-click the page and select Tab Order. You can then reorder the controls in whatever way you want.

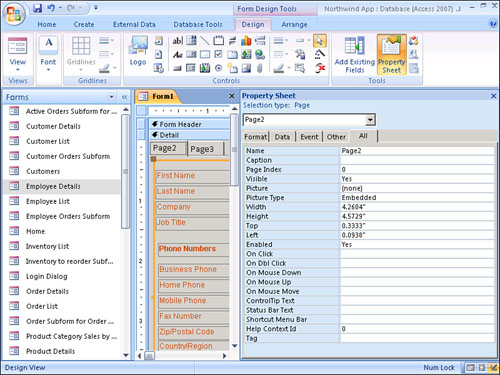

Changing the Properties of the Tab Control

To change the properties of the Tab control, click to select it rather than a specific page. You can tell whether you’ve selected the Tab control because the words Tab Control appear in the upper-left corner of the title bar of the property sheet. A Tab control’s properties include its name, whether it is visible, the text font on the tabs, and more (see Figure 10.9).

Figure 10.9. Viewing properties of a Tab control.

Changing the Properties of Each Page

To change the properties of each page, select a specific page of the Tab control. You can tell whether you’ve selected a specific page because the word Page is displayed in the upper-left corner of the title bar of the property page. Here, you can select a name for the page, the page’s caption, a picture for the page’s background, and more (see Figure 10.10).

Figure 10.10. Viewing properties of a Tab page.

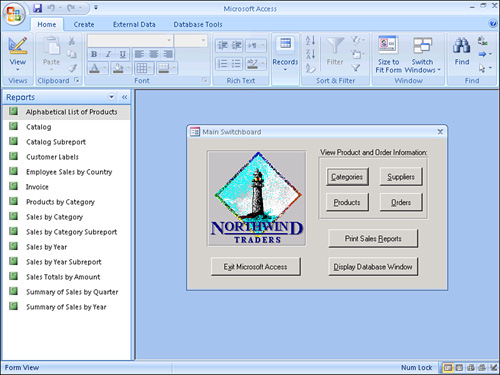

Switchboard Forms: Controlling Your Application

Using a Switchboard form is a great way to control your application. A Switchboard form is simply a form with command buttons that allow you to navigate to other Switchboard forms or to the forms and reports that make up your system.

Figure 10.11 shows a Switchboard form. It lets a user work with different components of the database. What differentiates a Switchboard form from other forms is that its purpose is limited to navigating through the application. It usually has a border style of Dialog, and it has no scrollbars, record selectors, or navigation buttons. Other than these characteristics, a Switchboard form is a normal form. There are many styles of Navigation forms; which one you use depends on your users’ needs.

Figure 10.11. An example of a Switchboard form.

Splash Screen Forms: Creating a Professional Opening to Your Application

Splash screens add professional polish to your applications and give your users something to look at while your programming code is setting up the application. Just follow these steps to create a Splash Screen form:

- Create a new form.

- Set the

Scrollbarsproperty toNeither, theRecord Selectorsproperty toNo, theNavigation Buttonsproperty toNo, theAuto Resizeproperty toYes, theAuto Centerproperty toYes, and theBorder StyletoNone. - Make the form pop-up and modal by setting the Pop Up and Modal properties of the form to Yes.

- Add a picture to the form and set the picture’s properties.

- Add any text you want on the form.

- Set the form’s timer interval property to the number of seconds you want the splash screen to be displayed.

- Code the form’s

Timerevent forDoCmd.Close. - Code the form’s

Unloadevent to open your main Switchboard form.

Because the Timer event of the Splash Screen form closes the form after the amount of time specified in the timer interval, the Splash Screen form unloads itself. While it’s unloading, it loads a Switchboard form. The Splash Screen form included in CHAP10EX.ACCDB is called frmSplash. When it unloads, it opens the frmSwitchboard form.

You can implement a Splash Screen form in many other ways. For example, you can call a Splash Screen form from a Startup form; its Open event simply needs to open the Splash Screen form. The problem with this method is that if your application loads and unloads the Switchboard while the application is running, the Splash Screen is displayed again.

Tip

You can also display a splash screen by including a bitmap file with the same name as your database (ACCDB) in the same directory as the database file. When the application is loaded, the splash screen is displayed for a couple of seconds. The only disadvantage to this method is that you have less control over when, and how long, the splash screen is displayed.

Dialog Forms: Gathering Information

Dialog forms are typically used to gather information from the user. What makes them Dialog forms is that they’re modal, meaning that the user can’t go ahead with the application until the form is handled. You generally use Dialog forms when you must get specific information from your user before your application can continue processing. A custom Dialog form is simply a regular form that has a Dialog border style and has its Modal property set to Yes. Remember to give users a way to close the form; otherwise, they might close your modal form with the famous “Three-Finger Salute” (Ctrl+Alt+Del) or, even worse, by using the PC’s Reset button. The frmArchivePayments form in CHAP10EX.ACCDB is a custom Dialog form.

Tip

Although opening a form with its BorderStyle property set to Dialog and its Modal property set to Yes will prevent the user from clicking outside the form (thereby continuing the application), it does not halt the execution of the code that opened the form. Suppose the intent is to open a Dialog form to gather parameters for a report and then open a report based on those parameters. In this case, the OpenForm method used to open the form must include the acDialog option in its Windowmode argument. Otherwise, the code will continue after the OpenForm method and open the report before the parameters are collected from the user.

Using Built-In Dialog Boxes

Access comes with two built-in dialog boxes: the standard Windows message box and the input box. The FileDialog object introduced with Access 2002 gives you access to other commonly used dialog boxes.

Message Boxes

A message box is a predefined dialog box that you can incorporate into your applications; however, you can customize it by using parameters. The VBA language has a MsgBox statement, which just displays a message, and a MsgBox function, which can display a message and return a value based on the user’s response.

The message box in the VBA language is the same message box that is standard in most Windows applications, so most Windows users are already familiar with it. Rather than create your own dialog boxes to get standard responses from your users, you can use an existing, standard interface.

The MsgBox Function

The MsgBox function receives five parameters. The first parameter is the message that you want to display. The second is a numeric value indicating which buttons and icons you want to display. Tables 10.1 and 10.2 list the values that you can numerically add to create the second parameter. You can substitute the intrinsic constants in the table for the numeric values, if you want.

Table 10.1. Values Indicating the Buttons That a Message Box Can Display

Table 10.2. Values Indicating the Icons That a Message Box Can Display

You must numerically add the values in Table 10.1 to one of the values in Table 10.2 if you want to include an icon other than the dialog box’s default icon.

MsgBox’s third parameter is the message box’s title. Its fourth and fifth parameters are the Help file and context ID that you want available if the user selects Help while the dialog box is displayed. The MsgBox function syntax looks like this:

MsgBox "This is a Message", vbInformation, "This is a Title"

This example displays the message "This is a Message" and the information icon. The title for the message box is "This is a Title". The message box also has an OK button that’s used to close the dialog box.

The MsgBox function is normally used to display just an OK button, but it can also be used to allow a user to select from a variety of standard button combinations. When used in this way, it returns a value indicating which button the user selected.

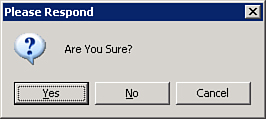

In the following example, the message box displays Yes, No, and Cancel buttons:

This message box also displays the Question icon (see Figure 10.12). The Function call returns a value stored in the Integer variable intAnswer.

Figure 10.12. The dialog box displayed by the MsgBox function.

After you have placed the return value into a variable, you can easily introduce logic into your program to respond to the user’s selection, as shown in this example:

This code evaluates the user’s response and displays a message based on her answer. Of course, in a real-life situation, the code in the Case statements would be more practical. Table 10.3 lists the values returned from the MsgBox function, depending on which button the user selected.

Table 10.3. Values Returned from the MsgBox Function

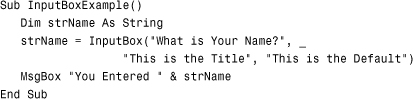

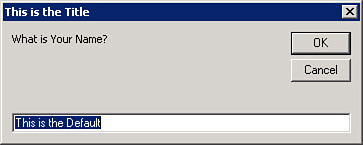

Input Boxes

The InputBox function displays a dialog box containing a simple text box. It returns the text that the user typed in the text box and looks like this:

This subroutine displays the input box shown in Figure 10.13. Notice that the first parameter is the message, the second is the title, and the third is the default value. The second and third parameters are optional.

Figure 10.13. An example of using the InputBox function to gather information.

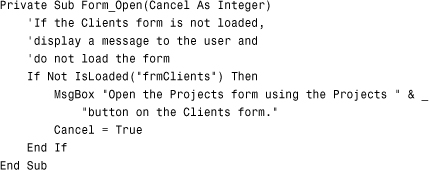

The FileDialog Object

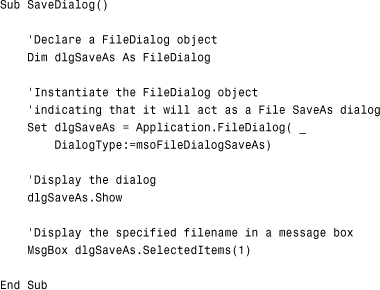

The FileDialog object was introduced with Access 2002. This object allows you to easily display the common dialog boxes previously available only by using the Common Dialog ActiveX control. Here’s an example of how FileDialog works:

The code in the example declares a FileDialog object. It instantiates the object, setting its type to a File Save As dialog box. It shows the dialog box and then displays the first selected file in a message box. Here’s another example:

This code once again declares a FileDialog object. When the code instantiates the object, it designates the dialog box type as a File Open dialog box. It sets the AllowMultiSelect property of the dialog box to allow multiple selections in the dialog box. It displays the dialog box and then displays the first selected file in a message box.

Taking Advantage of Built-In, Form-Filtering Features

Access has several form-filtering features that are part of the user interface. You can opt to include these features in your application, omit them from your application entirely, or control their behavior. For your application to control their behavior, it needs to respond to the Filter event, which it does by detecting when a filter is placed on the data in the form. When it has detected a filter, the code in the Filter event executes.

Sometimes you might want to alter the standard behavior of a filter command. You might want to display a special message to a user, for example, or take a specific action in your code. You might also want your application to respond to a Filter event because you want to alter the form’s display before the filter is applied. For example, if a certain filter is in place, you might want to hide or disable certain fields. When the filter is removed, you could then return the form’s appearance to normal.

Fortunately, Access not only lets you know that the Filter event occurred, but it also lets you know how the filter was invoked. Armed with this information, you can intercept and change the filtering behavior as needed.

When a user chooses Filter By Form or Advanced Filter/Sort, the FilterType parameter is filled with a value that indicates how the filter was invoked. If the user invokes the filter by selecting Filter By Form, the FilterType parameter equals the constant acFilterByForm; however, if she selects Advanced Filter/Sort, the FilterType parameter equals the constant acFilterAdvanced. The following code demonstrates how to use these constants:

This code, placed in the form’s Filter event, evaluates the filter type. If the user selected Filter By Form, the code displays a message box, and the filtering proceeds as usual. However, if the user selected Advanced Filter/Sort, she’s told she can’t do this, and the filter process is canceled.

You can not only check how the filter was invoked, but you can also intercept the process when the filter is applied. You do this by placing code in the form’s ApplyFilter event, as shown in this example:

This code evaluates the value of the ApplyType parameter. If it’s equal to the constant acApplyFilter, a message box is displayed, verifying that the user wants to apply the filter. If the user responds Yes, the filter is applied; otherwise, the filter is canceled.

Including Objects from Other Applications: Linking Versus Embedding

Microsoft Access is an ActiveX client application, meaning that it can contain objects from other applications. All versions of Access subsequent to Access 97 are also ActiveX server applications. Using Access as an ActiveX server is covered in Chapter 24, “Automation: Communicating with Other Applications.” Access’s capability to control other applications with programming code is also covered in Chapter 24. In the following sections, you learn how to link to and embed objects in your Access forms.

Bound OLE Objects

Bound OLE objects are tied to the data in an OLE field within a table in your database. An example is the Picture field that’s part of the Categories table in the Northwind database. The field type of the Categories table that supports multimedia data is of the OLE Object field type. This means that each record in the table can contain a unique OLE object. The Categories form contains a bound OLE control, whose control source is the Picture field from the Categories table.

If you double-click the picture associated with a category, you can edit the OLE object in-place. The picture associated with the category is actually embedded in the Categories table. This means that the data associated with the OLE object is stored as part of the Access database (ACCDB) file, within the Categories table. Embedded objects, if they support the OLE 2.0 standard, can be modified in-place. This Microsoft feature is called In-Place activation.

To insert a new object, take the following steps:

- Move to the record that will contain the OLE object.

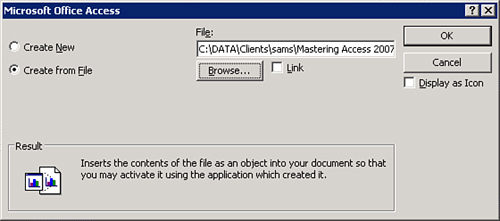

- Right-click the OLE Object control and select Insert Object to open the Insert Object dialog box.

- Select an object type. Select Create New if you want to create an embedded object or select Create from File if you want to link to or embed an existing file.

- If you select Create from File, the Insert Object dialog box changes to look like the one shown in Figure 10.14.

Figure 10.14. The Insert Object dialog box as it appears when you select Create from File.

- Select Link if you want to link to the existing file. Don’t check Link if you want to embed the existing file. If you link to the file, the Access table will have a reference to the file as well as to the presentation data (a bitmap) for the object. If you embed the file, Access copies the original file, placing the copy in the Access table.

- Click Browse and select the file you want to link to or embed.

- Click OK.

Access returns you to the record that you were working with, and you can continue working with that record or move to another record.

If you double-click a linked object, you launch its source application; you don’t get In-Place activation (see Figure 10.15).

Figure 10.15. Editing a linked object.

Unbound OLE Objects

Unbound OLE objects aren’t stored in your database. Instead, they are part of the form they were created in. Like bound OLE objects, unbound OLE objects can be linked or embedded. You create an unbound OLE object by adding an unbound object frame to the form.

Using OpenArgs

The OpenArgs property gives you a way to pass information to a form as it’s being opened. The OpenArgs argument of the OpenForm method is used to populate a form’s OpenArgs property at runtime. It works like this:

This code is found in the time and billing application’s frmPayments form. It opens the frmPaymentMethods form when a new method of payment is added to the cboPaymentMethodID combo box. It sends the frmPaymentMethods form an OpenArg of whatever data is added to the combo box. The Load event of the frmPaymentMethods form looks like this:

This code sets the txtPaymentMethod text box value to the value passed as the opening argument. This occurs only when the frmPaymentMethods form is opened from the frmPayments form.

Switching a Form’s RecordSource

Many developers don’t realize how easy it is to switch a form’s RecordSource property at runtime. This is a great way to use the same form to display data from more than one table or query containing the same fields. It’s also a great way to limit the data that’s displayed in a form at a particular moment. Using the technique of altering a form’s RecordSource property at runtime, as shown in Listing 10.1, you can dramatically improve performance, especially for a client/server application. This example is found in the frmShowSales form of the CHAP10EX database (see Figure 10.16).

Figure 10.16. Changing the RecordSource property of a form at runtime.

Listing 10.1. Altering a Form’s RecordSource at Runtime

Listing 10.1 begins by storing the value of the optSales option group on the frmShowSales main form into a Long Integer variable. It calls the ShowSalesValue function, which declares three constants; then it evaluates the parameter that was passed to it (the Long Integer variable containing the option group value). Based on this value, it builds a selection string for the subtotal value. This selection string becomes part of the SQL statement used for the subform’s record source and limits the range of sales values displayed on the subform.

The ShowSales routine builds a string containing a SQL statement, which selects all required fields from the tblCustomers table and qryOrderSubtotals query. It builds a WHERE clause that includes the txtBeginningDate and txtEndingDate from the main form as well as the string returned from the ShowSalesValue function.

After the SQL statement has been built, the RecordSource property of the fsubShowSales subform control is set equal to the SQL statement. The RecordCount property of the RecordsetClone (the form’s underlying recordset) is evaluated to determine whether any records meet the criteria specified in the RecordSource. If the record count is zero, no records are displayed in the subform, and the user is warned that no records met the criteria. However, if records are found, the form’s Detail section is enabled, and focus is moved to the subform.

Learning Power Combo Box and List Box Techniques

Combo and list boxes are very powerful. Being able to properly respond to a combo box’s NotInList event, to populate a combo box by using code, and to select multiple entries in a list box are essential skills of an experienced Access programmer. They’re covered in detail in the following sections.

Handling the NotInList Event

As previously discussed, the NotInList event occurs when a user types a value in the text box portion of a combo box that’s not found in the combo box list. This event takes place only if the LimitToList property of the combo box is set to True. It’s up to you whether you respond to this event.

You might want to respond with something other than the default error message when the LimitToList property is set to True and the user tries to add an entry. For example, if a user is entering an order and she enters the name of a new customer, you could react by displaying a message box asking whether she really wants to add the new customer. If the user responds affirmatively, you can display a customer form.

After you have set the LimitToList property to True, any code you place in the NotInList event is executed whenever the user tries to type an entry that’s not found in the combo box. The following is an example:

When you place this code in the NotInList event procedure of your combo box, it displays a message asking the user whether she wants to add the payment method. If the user responds No, she is returned to the form without the standard error message being displayed, but she still must enter a valid value in the combo box. If the user responds Yes, she is placed in the frmPaymentMethods form, ready to add the payment method whose name she typed.

The NotInList event procedure accepts a response argument, which is where you can tell VBA what to do after your code executes. Any one of the following three constants can be placed in the response argument:

acDataErrAdded—This constant is used if your code adds the new value into the record source for the combo box. This code requeries the combo box, adding the new value to the list.acDataErrDisplay—This constant is used if you want VBA to display the default error message.acDataErrContinue—This constant is used if you want to suppress VBA’s error message, using your own instead. Access still requires that a valid entry be placed in the combo box.

Working with a Pop-Up Form

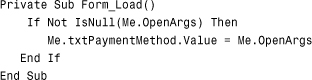

The NotInList technique just described employs the pop-up form. When the user opts to add the new payment method, the frmPaymentMethods form displays modally. This halts execution of the code in the form that loads the frmPaymentMethods form (in this case, the frmPayments form). The frmPaymentMethods form is considered a pop-up form because the form is modal, it uses information from the frmPayments form, and the frmPayments form reacts according to whether the OK or Cancel button is selected. The code in the Load event of the frmPaymentMethods form in the time and billing database appears as follows:

![]()

This code uses the information received as an opening argument to populate the txtPaymentMethod text box. No further code executes until the user clicks either the OK or the Cancel command button. If the user clicks the OK button, the following code executes:

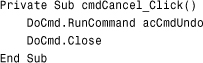

![]()

Notice that the preceding code hides, rather than closes, the frmPaymentMethods form. If the user clicks the Cancel button, this code executes:

The code under the Cancel button first undoes the changes that the user made. It then closes the frmPaymentMethods form. Once back in the NotInList event of the cboPaymentMethod combo box on the frmPayments form, the following code executes:

The code evaluates whether the frmPaymentMethods form is still loaded. If it is, the user must have clicked OK. The Response parameter is set to acDataErrAdded, designating that the new entry has been added to the combo box and to the underlying data source. The code then closes the frmPaymentMethods form.

If the frmPaymentMethods form is not loaded, the user must have clicked Cancel. The user is returned to the combo box where he must select another combo box entry. In summary, the steps are as follows:

- Open the pop-up form modally (with the

WindowModeparameter equal toacDialog). - Pass an

OpenArgsparameter, if desired. - When control returns to the original form, check to see whether the pop-up form is still loaded.

- If the pop-up form is still open, use its information and then close it.

Adding Items to a Combo Box or List Box at Runtime

Prior to Access 2002, it was very difficult to add and remove items from list boxes and combo boxes at runtime. Access 2002, Access 2003, and Access 2007 list boxes and combo boxes support two powerful methods that make it easier to programmatically manipulate these boxes at runtime. The AddItem method allows you to easily add items to a list box or a combo box. The RemoveItem method allows you to remove items from a combo box or a list box. Here’s an example:

This code is found in the frmSendToExcel form that’s part of the CHAP10EX database. It loops through all tables in the database, adding the name of each table to the lstTables list box. It then loops through each query in the database, once again adding each to the list box.

Handling Multiple Selections in a List Box

List boxes have a Multiselect property. When set to True, this property lets the user select multiple elements from the list box. Your code can then evaluate which elements are selected and perform some action based on the selected elements. The frmReportSelection form, found in the CHAP10EX database, illustrates the use of a multiselect list box. The code under the Click event of the Run Reports button looks like that shown in Listing 10.2.

Listing 10.2. Evaluating Which Items Are Selected in the Multiselect List Box

This code first checks to ensure that the list box is a multiselect list box. If it is, and at least one report is selected, the code loops through all the selected items in the list box. It prints each report that is selected.

Learning Power Subform Techniques

Many new Access developers don’t know the ins and outs of creating and modifying a subform and referring to subform controls, so here are some important points you should know when working with subforms:

- The easiest way to add a subform to a main form is to open the main form and then drag and drop the subform onto the main form.

- The subform control’s

LinkChildFieldsandLinkMasterFieldsproperties determine which fields in the main form link to which fields in the subform. A single field name, or a list of fields separated by semicolons, can be entered into these properties. When they are properly set, these properties make sure all records in the child form relate to the currently displayed record in the parent form.

Referring to Subform Controls

Many developers don’t know how to properly refer to subform controls. You must refer to any objects on the subform through the subform control on the main form, as shown in this example:

Forms.frmCustomer.fsubOrders

This example refers to the fsubOrders control on the frmCustomer form. If you want to refer to a specific control on the fsubOrders subform, you can then point at its controls collection. Here’s an example:

Forms.frmCustomer.fsubOrders!txtOrderID

You can also refer to the control on the subform implicitly, as shown in this example:

Forms!frmCustomer!subOrders!txtOrderID

Both of these methods refer to the txtOrderID control on the form in the fsubOrder control on the frmCustomer form. To change a property of this control, you would extend the syntax to look like this:

Forms.frmCustomer.fsubOrders!txtOrderID.Enabled = False

This code sets the Enabled property of the txtOrderID control on the form in the fsubOrders control to False.

Using Automatic Error Checking

In Access 2007, you can enable automatic error checking of forms. Error checking not only points out errors in a form but also provides suggestions for correcting them.

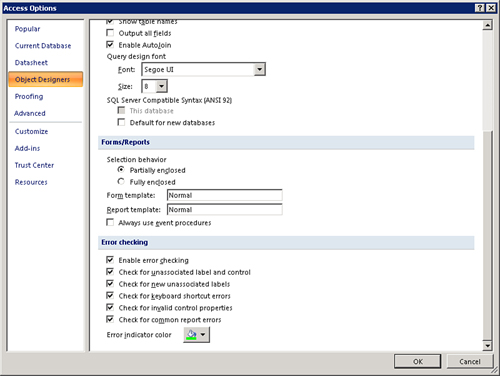

To activate error checking, click to select the Microsoft Access button and then click Access Options. Click to select the Object Designers tab (see Figure 10.17). Click the Enable Error Checking check box within the Error checking group of options to enable error checking. After you enable error checking, indicators appear on your form, letting you know that something is wrong (see Figure 10.18). You then click the indicator, and an explanation and suggestions appear for correcting the error (see Figure 10.19).

Figure 10.17. You can activate error checking from the Object Designers tab of the Access Options dialog box.

Figure 10.18. Indicators appear on your form, letting you know that something is wrong.

Figure 10.19. A menu appears, providing you with an explanation and suggestions for correcting the error.

The error checker will identify several categories of errors. They are shown in Table 10.4.

Table 10.4. Categories of Errors Identified by the Error Checker

If Access identifies several errors for the same control, the error indicator remains until all errors are corrected. If you choose to ignore an error, simply select the Ignore Error option on the Error Checking Options menu. This will clear the error indicator until you close and open the form again. Remember that via the Access Options, you can turn off error checking entirely (although I find this feature to be extremely valuable).

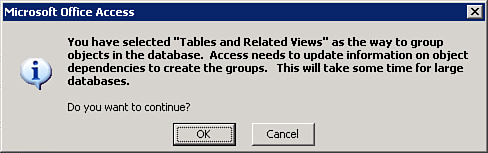

Viewing Object Dependencies

Microsoft added a wonderful feature to Access 2003. It enables you to view information about object dependencies. Here’s how it works:

- To invoke the Object Dependency feature, select Tables and Related Views from the Navigation Pane drop-down. The first time you perform this task for a database, a dialog box appears, prompting you to update object dependency information for the database (see Figure 10.20). After you click OK, Access updates the dependency information for the database and displays the object dependencies within the Navigation Pane (see Figure 10.21). In Figure 10.21, you can see all the objects that depend on the Categories table.

Figure 10.20. The first time you attempt to display object dependencies within a database, Access prompts you to update dependency information for that database.

Figure 10.21. The Navigation Pane shows you the objects that depend on the selected object.

Using AutoCorrect Options

The AutoCorrect feature minimizes the problems that occur when you rename tables, fields, queries, forms, reports, text boxes, or other controls. You enable AutoCorrect on the Current Database tab of the Access Options dialog box (see Figure 10.22).

Figure 10.22. You enable AutoCorrect on the Current Database tab of the Access Options dialog box.

You can enable AutoCorrect at one of three levels:

- Track Name AutoCorrect Info—Access simply keeps track of the name changes. It does not fix errors caused by renaming.

- Perform Name AutoCorrect—Access keeps track of changes and fixes all changes as they are made.

- Log Name Autocorrect Changes—In addition to tracking changes and fixing errors, this option provides you with a table that logs all changes made to the names of objects.

Propagating Field Properties

When you make a change to an inherited property in a table’s Design view, you can opt to propagate that change to the controls on your forms that are bound to that field. Here’s how it works:

- Open the table whose design you want to modify in Design view.

- Click in the field whose property you want to change.

- Click in the property whose value you want to change.

- Change the property and press Enter. If the property that you changed is inheritable, the Property Update Options button appears (see Figure 10.23).

Figure 10.23. The Property Update Options button appears for inheritable properties.

- Open the menu and select Update (see Figure 10.24). The Update Properties dialog box appears (see Figure 10.25). Select the forms and reports that contain the controls that you want to update. Click Yes to complete the process.

Figure 10.24. Open the menu and select Update.

Figure 10.25. The Update Properties dialog box allows you to select the forms and reports that you want to update.

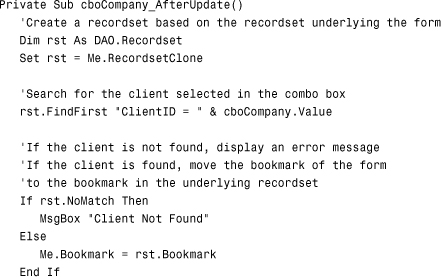

Synchronizing a Form with Its Underlying Recordset

You use a form’s RecordsetClone property to refer to its underlying recordset. You can manipulate this recordset independently of what’s currently being displayed on the form. Here’s an example:

This code creates an object variable that points at the form’s RecordsetClone. The recordset object variable can then be substituted for Me.RecordsetClone because it references the form’s underlying recordset. The example then uses the object variable to execute the FindFirst method. It searches for a record in the form’s underlying recordset whose ClientID is equal to the current combo box value. If a match is found, the form’s bookmark is synchronized with the bookmark of the form’s underlying recordset.

The RecordsetClone property allows you to navigate or operate on a form’s records independently of the form. This capability is often useful when you want to manipulate the data behind the form without affecting the appearance of the form. On the other hand, when you use the Recordset property of the form, the act of changing which record is current in the recordset returned by the form’s Recordset property also sets the current record of the form. Here’s an example:

Notice that you do not need to set the Bookmark property of the form equal to the Bookmark property of the recordset. They are one and the same.

Creating Custom Properties and Methods

Forms and reports are Class modules, which means they act as templates for objects you create instances of at runtime. Public procedures of a form and report become Custom properties and methods of the form object at runtime. Using VBA code, you can set the values of a form’s Custom properties and execute its methods.

Creating Custom Properties

You can create Custom properties of a form or report in one of two ways:

- Create

Publicvariables in the form or report. - Create

PropertyLetandPropertyGetroutines.

Creating and Using a Public Variable as a Form Property

The following steps are used to create and access a Custom form or report property based on a Public variable. The example is included in CHAP10EX.ACCDB in the forms frmPublicProperties and frmChangePublicProperty.

- Begin by creating the form that will contain the

Customproperty (Publicvariable). - Place a

Publicvariable in the General Declarations section of the form or report (see Figure 10.26).Figure 10.26. Creating a

Publicvariable in the General Declarations section of a Class module.

- Place code in the form or report that accesses the

Publicvariable. The code in Figure 10.26 creates aPublicvariable calledCustomCaption. The code behind theClickevent of thecmdChangeCaptioncommand button sets the form’s (frmPublicProperties)Captionproperty equal to the value of thePublicvariable. - Create a form, report, or module that modifies the value of the

Customproperty. Figure 10.27 shows a form calledfrmChangePublicProperty.Figure 10.27. Viewing the

frmChangePublicPropertyform.

- Add the code that modifies the value of the

Customproperty. The code behind theChangeCaptionbutton, as shown in Figure 10.26, modifies the value of theCustomproperty calledCustomCaptionthat’s found on thefrmPublicPropertiesform.

To test the Custom property created in the preceding example, run the frmPublicProperties form, which is in the CHAP10EX.MDB database on the sample code website. Click the Change Form Caption command button. Nothing happens because the value of the Custom property hasn’t been set. Open the frmChangePublicProperty form and click the Change Form Property command button. Return to frmPublicProperties and again click the Change Form Caption command button. The form’s caption should now change.

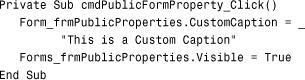

Close the frmPublicProperties form and try clicking the Change Form Property command button. A runtime error occurs, indicating that the form you’re referring to is not open. You can eliminate the error by placing the following code in the Click event of cmdPublicFormProperty:

This code modifies the value of the Public property by using the syntax Form_FormName.Property. If the form isn’t loaded, this syntax loads the form but leaves it hidden. The next command sets the form’s Visible property to True.

Creating and Using Custom Properties with PropertyLet and PropertyGet Routines

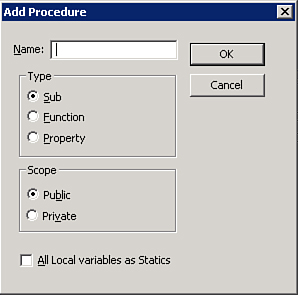

A PropertyLet routine is a special type of subroutine that automatically executes whenever the property’s value is changed. A PropertyGet routine is another special subroutine that automatically executes whenever the value of the Custom property is retrieved. Instead of using a Public variable to create a property, you insert two special routines: PropertyLet and PropertyGet. This example is found in CHAP10EX.ACCDB in the frmPropertyGetLet and frmChangeWithLet forms. To insert the PropertyLet and PropertyGet routines, follow these steps:

- Choose Insert, Procedure. The dialog box shown in Figure 10.28 appears.

Figure 10.28. Starting a new procedure with the Add Procedure dialog box.

- Type the name of the procedure in the Name text box.

- Select Property from the Type option buttons.

- Select Public as the Scope so that the property is visible outside the form.

- Click OK. The

PropertyGetandPropertyLetsubroutines are inserted in the module (see Figure 10.29).Figure 10.29. The

PropertyGetandPropertyLetsubroutines inserted in the module.

Notice that the Click event code for the cmdChangeCaption command button hasn’t changed. The PropertyLet routine, which automatically executes whenever the value of the CustomCaption property is changed, takes the uppercase value of what it’s being sent and places it in a Private variable called mstrCustomCaption. The PropertyGet routine takes the value of the Private variable and returns it to whoever asked for the value of the property. The following code is placed in the form called frmChangeWithLet:

This routine tries to set the value of the Custom property called CustomCaption to the value "This is a Custom Caption". Because the property’s value is being changed, the PropertyLet routine in frmPropertyGetLet is automatically executed. It looks like this:

![]()

The PropertyLet routine receives the value "This is a Custom Caption" as a parameter. It uses the UCase function to manipulate the value it was passed and convert it to uppercase. It then places the manipulated value into a Private variable called mstrCustomCaption. The PropertyGet routine isn’t executed until the user clicks the cmdChangeCaption button in the frmPropertyGetLet form. The Click event of cmdChangeCaption looks like this:

![]()

Because this routine needs to retrieve the value of the Custom property CustomCaption, the PropertyGet routine automatically executes:

![]()

The PropertyGet routine takes the value of the Private variable, set by the PropertyLet routine, and returns it as the value of the property.

You might wonder why this method is preferable to declaring a Public variable. Using the UCase function within PropertyLet should illustrate why. Whenever you expose a Public variable, you can’t do much to validate or manipulate the value you receive. The PropertyLet routine gives you the opportunity to validate and manipulate the value to which the property is being set. By placing the manipulated value in a Private variable and then retrieving the Private variable’s value when the property is returned, you gain full control over what happens internally to the property.

Note

This section provides an introduction to custom properties and methods. You can find a comprehensive discussion of custom classes, properties, and methods in Chapter 14, “Exploiting the Power of Class Modules.”

Creating Custom Methods

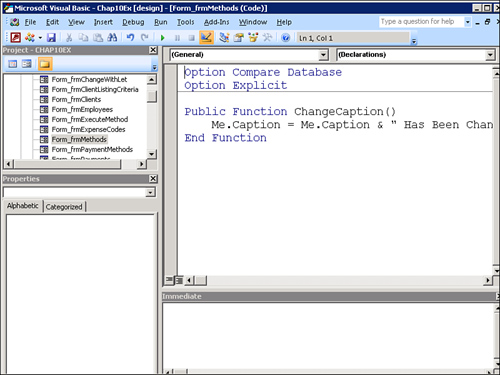

Custom methods are simply Public functions and subroutines placed in a Form module or a Report module. As you will see, they can be called by using the Object.Method syntax. Here are the steps involved in creating a Custom method; they are found in CHAP10EX.ACCDB in the forms frmMethods and frmExecuteMethod:

- Open the form or report that will contain the

Custommethod. - Create a

Publicfunction or subroutine (see Figure 10.30).Figure 10.30. Using the custom method

ChangeCaption.

- Open the Form module, Report module, or Code module that executes the

Custommethod. - Use the

Object.Methodsyntax to invoke theCustommethod (see Figure 10.31).Figure 10.31. The

Clickevent code behind the Execute Method button.

Figure 10.30 shows the Custom method ChangeCaption found in the frmMethods form. The method changes the form’s caption. Figure 10.31 shows the Click event of cmdExecuteMethod found in the frmExecuteMethod form. It issues the ChangeCaption method of the frmMethods form and then sets the form’s Visible property to True.

Practical Examples: Applying Advanced Techniques to Your Application

You can use many examples in this chapter in all the applications that you build. To polish your application, build a startup form that displays a splash screen and then performs some setup functions. The CHAP10EX.ACCDB file contains these examples.

Getting Things Going with a Startup Form

The frmSwitchboard form is responsible both for displaying the splash screen and for performing the necessary setup code. The code in the Load event of the frmSwitchboard form looks like this:

The Form_Load event first invokes an hourglass. It then opens the frmSplash form. Next, it calls the GetCompanyInfo routine to fill in the CompanyInfo type structure that is eventually used throughout the application. (Type structures are covered in Chapter 13, “Advanced VBA Techniques.”) Finally, Form_Load turns off the hourglass.

Building a Splash Screen

The splash screen, shown in Figure 10.32, is called frmSplash. Its timer interval is set to 3,000 milliseconds (3 seconds), and its Timer event looks like this:

Figure 10.32. Using an existing form as a splash screen.

The Timer event unloads the form. The frmSplash Pop-up property is set to Yes, and its border is set to None. Record selectors and navigation buttons have been removed.

Summary

Forms are the centerpiece of most Access applications, so it’s vital that you are able to fully harness their power and flexibility. This chapter showed you how to work with Form and Control events. You saw many examples illustrating when and how to leverage the event routines associated with forms and specific controls. You also learned about the types of forms available, their uses in your applications, and how you can build them. Finally, you learned several power techniques that will help you develop complex forms.