Up until this point, we’ve written applications with a single view controller. While there certainly is a lot you can do with a single view, the real power of the iOS platform emerges when you can switch out views based on user input. Multiview applications come in several different flavors, but the underlying mechanism is the same, regardless of how the app may appear on the screen.

In this chapter, we’re going to focus on the structure of multiview applications and the basics of swapping content views by building our own multiview application from scratch. We will write our own custom controller class that switches between two different content views, establishing a strong foundation for taking advantage of the various multiview controllers that Apple provides.

But before we start building our application, let’s see how multiple-view applications can be useful.

Common Types of Multiview Apps

Strictly speaking, we have worked with multiple views in our previous applications since buttons, labels, and other controls are all subclasses of UIView, and they can all go into the view hierarchy. But when Apple uses the term view in documentation, it is generally referring to a UIView or one of its subclasses that has a corresponding view controller. These types of views are also sometimes referred to as content viewsbecause they are the primary container for the content of your application.

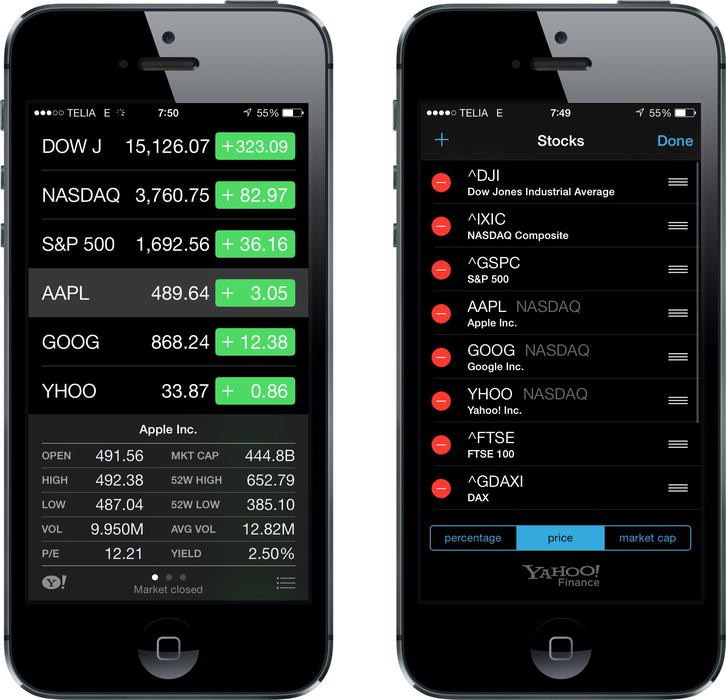

The simplest example of a multiview application is a utility application. A utility application focuses primarily on a single view, but offers a second view that can be used to configure the application or to provide more detail than the primary view. The Stocks application that ships with iPhone is a good example (see Figure 6-1). If you click the button in the lower-right corner, the view transitions to a configuration view that lets you configure the list of stocks tracked by the application.

Figure 6-1. The Stocks application that ships with iPhone has two views: one to display the data and another to configure the stock list

There are also several tab bar applications that ship with the iPhone, including the Phone application (see Figure 6-2) and the Clock application. A tab bar application is a multiview application that displays a row of buttons, called the tab bar, at the bottom of the screen. Tapping one of the buttons causes a new view controller to become active and a new view to be shown. In the Phone application, for example, tapping Contacts shows a different view than the one shown when you tap Keypad.

Figure 6-2. The Phone application is an example of a multiview application using a tab bar

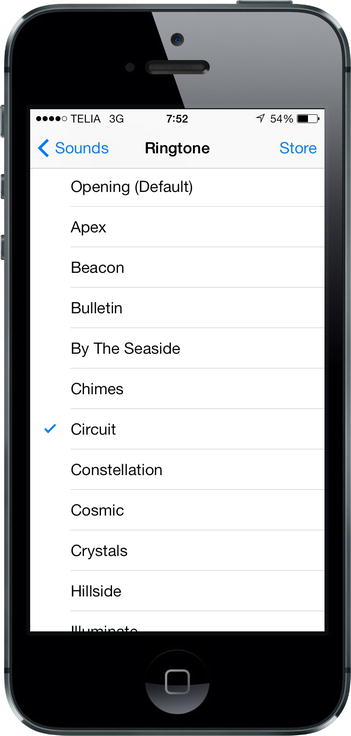

Another common kind of multiview iPhone application is the navigation-based application, which features a navigation controller that uses a navigation bar to control a hierarchical series of views. The Settings application is a good example. In Settings, the first view you get is a series of rows, each row corresponding to a cluster of settings or a specific app. Touching one of those rows takes you to a new view where you can customize one particular set of settings. Some views present a list that allows you to dive even deeper. The navigation controller keeps track of how deep you go and gives you a control to let you make your way back to the previous view.

For example, if you select the Sounds preference, you’ll be presented a view with a list of sound-related options. At the top of that view is a navigation bar with a left arrow labeled Settings that takes you back to the previous view if you tap it. Within the sound options is a row labeled Ringtone. Tap Ringtone, and you’re taken to a new view featuring a list of ringtones and a navigation bar that takes you back to the main Sounds preference view (see Figure 6-3). A navigation-based application is useful when you want to present a hierarchy of views.

Figure 6-3. The iPhone Settings application is an example of a multiview application using a navigation bar

On the iPad, most navigation-based applications, such as Mail, are implemented using a split view, where the navigation elements appear on the left side of the screen, and the item you select to view or edit appears on the right. You’ll learn more about split views and other iPad-specific GUI elements in Chapter 10.

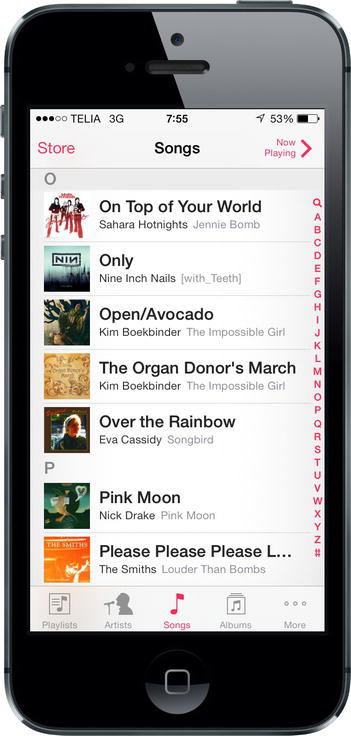

Because views are themselves hierarchical in nature, it’s even possible to combine different mechanisms for swapping views within a single application. For example, the iPhone’s Music application uses a tab bar to switch between different methods of organizing your music, and a navigation controller and its associated navigation bar to allow you to browse your music based on that selection. In Figure 6-4, the tab bar is at the bottom of the screen, and the navigation bar is at the top of the screen.

Figure 6-4. The Music application uses both a navigation bar and a tab bar

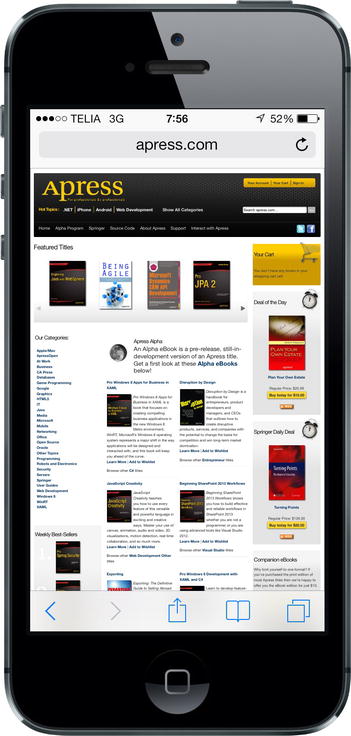

Some applications use a toolbar, which is often confused with a tab bar. A tab bar is used for selecting one and only one option from among two or more options. A toolbar can hold buttons and certain other controls, but those items are not mutually exclusive. A perfect example of a toolbar is at the bottom of the main Safari view (see Figure 6-5). If you compare the toolbar at the bottom of the Safari view with the tab bar at the bottom of the Phone or Music application, you’ll find the two pretty easy to tell apart. The tab bar has multiple segments, exactly one of which (the selected one) is highlighted with a tint color; but on a toolbar, normally every enabled button is highlighted.

Figure 6-5. Mobile Safari features a toolbar at the bottom. The toolbar is like a free-form bar that allows you to include a variety of controls

Each of these multiview application types uses a specific controller class from the UIKit. Tab bar interfaces are implemented using the class UITabBarController, and navigation interfaces are implemented using UINavigationController. We’ll describe their use in detail in the next few chapters.

The Architecture of a Multiview Application

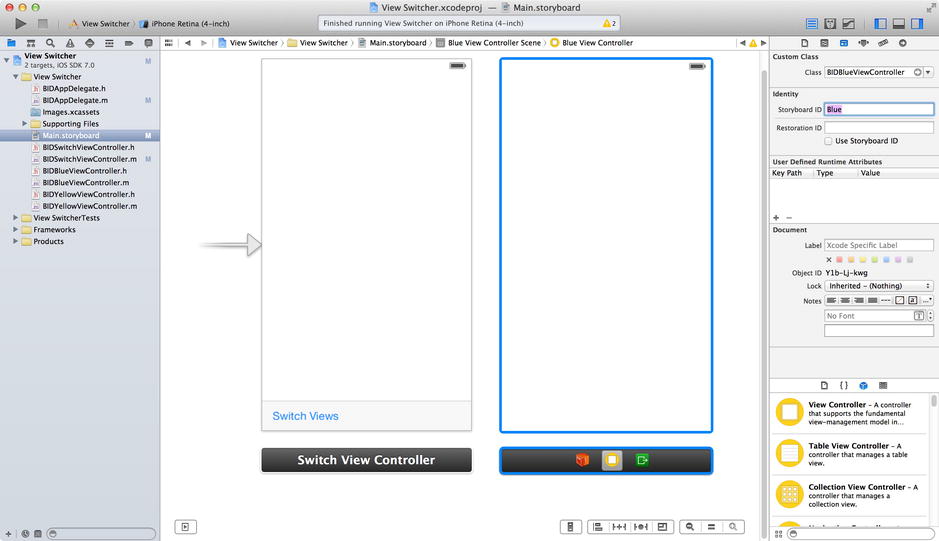

The application we’re going to build in this chapter, View Switcher, is fairly simple in appearance; however, in terms of the code we’re going to write, it’s by far the most complex application we’ve yet tackled. View Switcher will consist of three different controllers, a storyboard, and an application delegate.

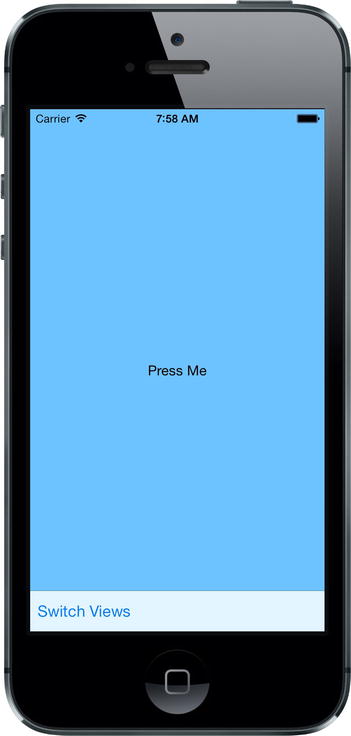

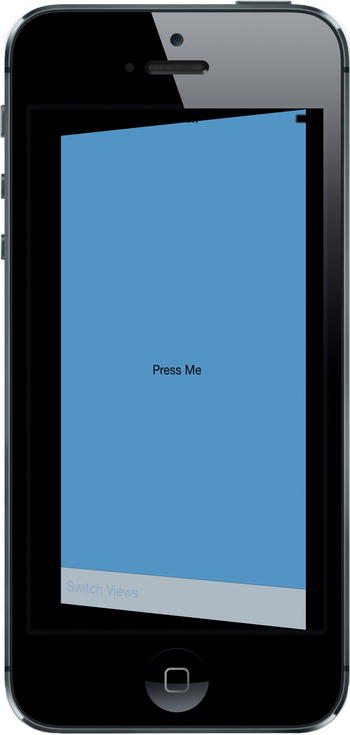

When first launched, View Switcher will look like Figure 6-6, with a toolbar at the bottom containing a single button. The rest of the view will contain a blue background and a button yearning to be pressed.

Figure 6-6. When you first launch the View Switcher application, you’ll see a blue view with a button and a toolbar with its own button

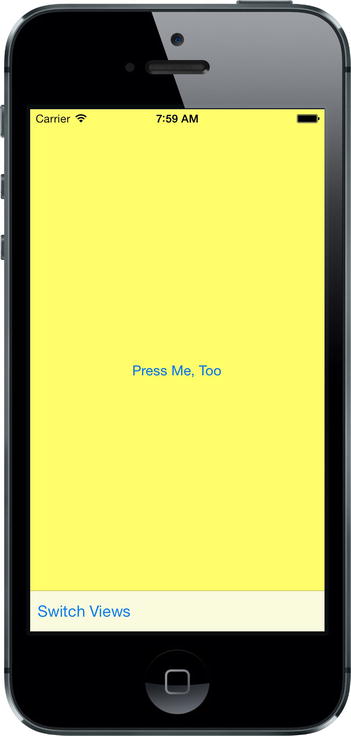

When the Switch Views button is pressed, the background will turn yellow, and the button’s title will change (see Figure 6-7).

Figure 6-7. When you press the Switch Views button, the blue view flips over to reveal the yellow view

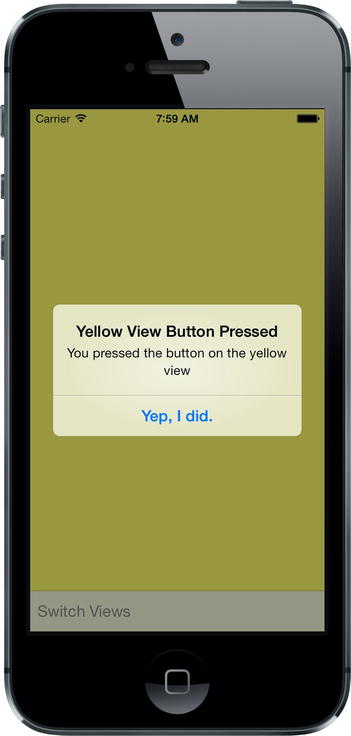

If either the Press Me or Press Me, Too button is pressed, an alert will pop up indicating which view’s button was pressed (see Figure 6-8).

Figure 6-8. When the Press Me or Press Me, Too button is pressed, an alert is displayed

Although we could achieve this same functionality by writing a single-view application, we’re taking this more complex approach to demonstrate the mechanics of a multiview application. There are actually three view controllers interacting in this simple application: one that controls the blue view, one that controls the yellow view, and a third special controller that swaps the other two in and out when the Switch Views button is pressed.

Before we start building our application, let’s talk about the way iPhone multiview applications are put together. Most multiview applications use the same basic pattern.

The Root Controller

The storyboard is a key player here since it will contain all the views and view controllers for our application. We’re going to make an empty storyboard, and then we’ll add an instance of a controller class that is responsible for managing which other view is currently being shown to the user. We call this controller the root controller (as in “the root of the tree” or “the root of all evil”) because it is the first controller the user sees and the controller that is loaded when the application loads. This root controller is often an instance of UINavigationController or UITabBarController, although it can also be a custom subclass of UIViewController.

In a multiview application, the job of the root controller is to take two or more other views and present them to the user as appropriate, based on the user’s input. A tab bar controller, for example, will swap in different views and view controllers based on which tab bar item was last tapped. A navigation controller will do the same thing as the user drills down and backs up through hierarchical data.

Note The root controller is the primary view controller for the application; and, as such, it is the view that specifies whether it is OK to automatically rotate to a new orientation. However, the root controller can pass responsibility for tasks like that to the currently active controller.

In multiview applications, most of the screen will be taken up by a content view, and each content view will have its own controller with its own outlets and actions. In a tab bar application, for example, taps on the tab bar will go to the tab bar controller, but taps anywhere else on the screen will go to the controller that corresponds to the content view currently being displayed.

Anatomy of a Content View

In a multiview application, each view controller controls a content view, and these content views are where the bulk of your application’s user interface is built. Taken together, each of these pairings is called a scene within a storyboard. Each scene consists of a view controller and a content view, which may be an instance of UIView or one of its subclasses. Unless you are doing something really unusual, your content view will always have an associated view controller and will sometimes subclass UIView. Although you can create your interface in code rather than using Interface Builder, few people choose that route because it is more time-consuming and the code is difficult to maintain.

In this project, we’ll be creating a new controller class for each content view. Our root controller controls a content view that consists of a toolbar that occupies the bottom of the screen. The root controller then loads a blue view controller, placing the blue content view as a subview to the root controller view. When the root controller’s Switch Views button (the button is in the toolbar) is pressed, the root controller swaps out the blue view controller and swaps in a yellow view controller, instantiating that controller if it needs to do so. Confused? If so, don’t worry because this will become clearer as we walk through the code.

Building View Switcher

Enough theory! Let’s go ahead and build our project. Select File ![]() New

New ![]() Project… or press

Project… or press ![]()

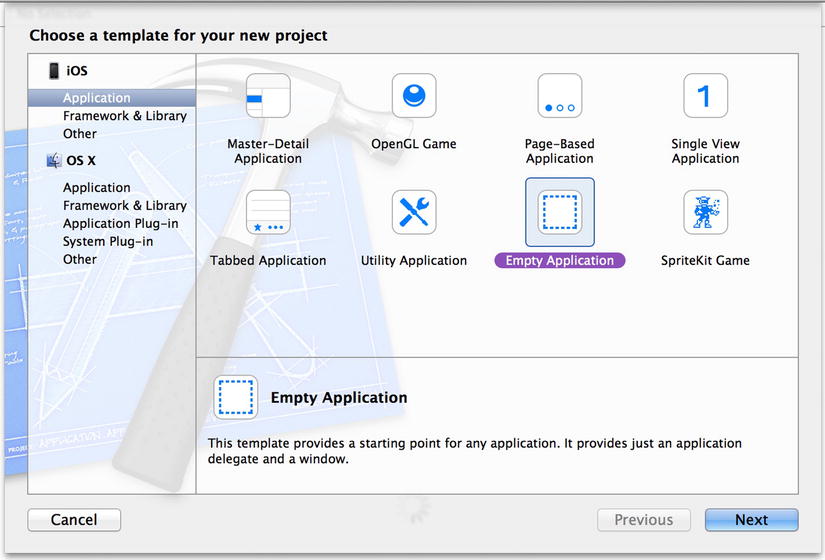

![]() N. When the template selection sheet opens, select Empty Application (see Figure 6-9), and then click Next. On the next page of the assistant, enter View Switcher as the Product Name, leave BID as the Class Prefix, and set the Device Family pop-up button to iPhone. Also make sure the checkbox labeled Use Core Data is unchecked. When everything is set up correctly, click Next to continue. On the next screen, navigate to wherever you’re saving your projects on disk and click the Create button to create a new project directory.

N. When the template selection sheet opens, select Empty Application (see Figure 6-9), and then click Next. On the next page of the assistant, enter View Switcher as the Product Name, leave BID as the Class Prefix, and set the Device Family pop-up button to iPhone. Also make sure the checkbox labeled Use Core Data is unchecked. When everything is set up correctly, click Next to continue. On the next screen, navigate to wherever you’re saving your projects on disk and click the Create button to create a new project directory.

Figure 6-9. Creating a new project using the Empty Application project template

The template we just selected is actually even simpler than the Single View Application template we’ve been using up to now. This template will give us an application delegate that creates its own window, an asset catalog, and nothing else—no views, no controllers, no nothing.

Note The window is the most basic container in iOS. Each app has exactly one window that belongs to it, though it is possible to see more than one window on the screen at a time. For example, if your app is running and your device receives an SMS or iMessage, you’ll see the message displayed in its own window, in front of your app’s window. Your app can’t access that overlaid window because it belongs to the Messages app.

You won’t use the Empty Application template very often when you’re creating applications; but by starting from nothing in this example, you’ll really get a feel for the way multiview applications are put together.

If they’re not expanded already, take a second to expand the View Switcher folder in the project navigator, as well as the Supporting Files folder it contains. Inside the View Switcher folder, you’ll find the two files that implement the application delegate. Within the Supporting Files folder, you’ll find the View Switcher-Info.plist file, the InfoPlist.strings file (which contains the localized versions of your Info.plist file), the standard main.m, and the precompiled header file (View Switcher-Prefix.pch). Everything else we need for our application, we must create.

Creating Our View Controller and Storyboard

One of the more daunting aspects of building a multiview application from scratch is that we need to create several interconnected objects. We’re going to create all the files that will make up our application before we do anything in Interface Builder and before we write any code. By creating all the files first, we’ll be able to use Xcode’s Code Sense feature to write our code faster. If a class hasn’t been declared, Code Sense has no way to know about it, so we would need to type its name in full every time, which takes longer and is more error-prone.

Fortunately, in addition to project templates, Xcode also provides file templates for many standard file types, which helps simplify the process of creating the basic skeleton of our application.

Single-click the View Switcher folder in the project navigator, and then press ![]() N or select File

N or select File ![]() New

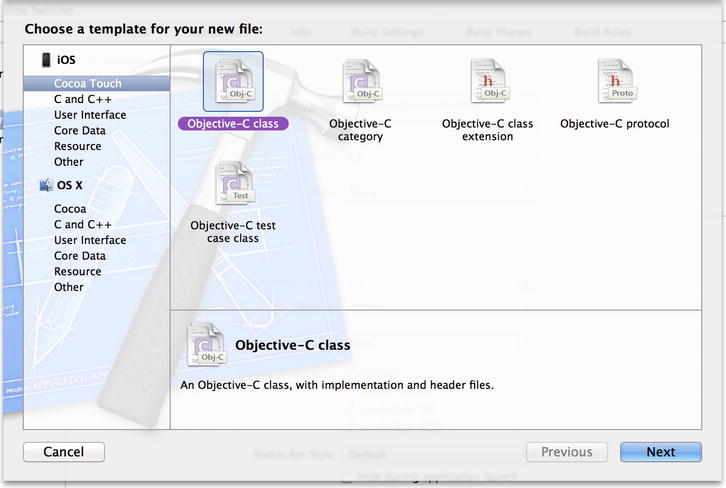

New ![]() File…. Take a look at the window that opens (see Figure 6-10).

File…. Take a look at the window that opens (see Figure 6-10).

Figure 6-10. The template we’ll use to create a new view controller subclass

If you select Cocoa Touch from the left pane, you will be given templates for a number of common Objective-C constructs, such as classes, categories, and so on. Select Objective-C Class and click Next. On the next page of the assistant, you’ll see two fields labeled Class and Subclass of. In the Subclass of field, enter UIViewController to tell Xcode which existing class should be the parent of our new class. You’ll see that Xcode starts to fill in a value in the Class text field. Change that value to BIDSwitchViewController, and then direct your attention to the other controls that let you configure the subclass:

- The second is a checkbox labeled Targeted for iPad. If it’s checked by default, you should uncheck it now (since we’re not making an iPad GUI).

- The third is another checkbox, labeled With XIB for user interface. If that box is checked, uncheck it as well. If you left that checkbox checked, Xcode would create a nib file that corresponds to this controller class. We’re going to define our entire GUI in one storyboard file instead, so leave this unchecked.

Click Next. A window appears that lets you choose a particular directory in which to save the files and pick a group and target for your files. By default, this window will show the directory most relevant to the folder you selected in the project navigator. For the sake of consistency, you’ll want to save the new class into the View Switcher folder, which Xcode set up when you created this project; it should already contain the BIDAppDelegate class. That’s where Xcode puts all of the Objective-C classes that are created as part of the project, and it’s as good a place as any for you to put your own classes.

About halfway down the window, you’ll find the Group pop-up list. You’ll want to add the new files to the View Switcher group. Finally, make sure the View Switcher target is selected in the Targets list before clicking the Create button.

Xcode should add two files to your View Switcher folder: BIDSwitchViewController.h and BIDSwitchViewController.m. BIDSwitchViewController will be your root controller—the controller that swaps the other views in and out. Now, we need to create the controllers for the two content views that will be swapped in and out. Repeat the same steps two more times to create BIDBlueViewController.m, BIDYellowViewController.m, and their .h counterparts, adding them to the same spot in the project hierarchy.

Caution Make sure you check your spelling, as a typo here will create classes that don’t match the source code later in the chapter.

Our next step is to create a storyboard, where we’ll later configure a scene for each of the content views we just created. Single-click the View Switcher folder in the project navigator, and then press ![]() N or select File

N or select File ![]() New

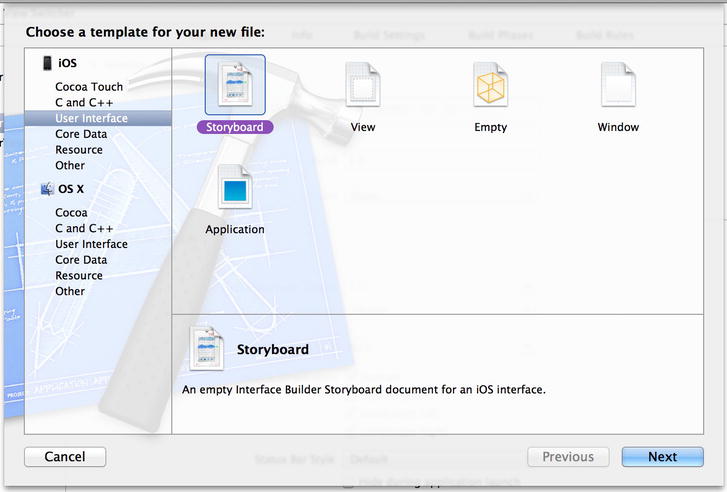

New ![]() File…. again. This time, select User Interface under the iOS heading in the left pane (see Figure 6-11). Next, select the icon for the Storyboard template, which will create an empty storyboard. Click Next. On the next screen, select iPhone from the Device Family pop-up, and then click the Next button.

File…. again. This time, select User Interface under the iOS heading in the left pane (see Figure 6-11). Next, select the icon for the Storyboard template, which will create an empty storyboard. Click Next. On the next screen, select iPhone from the Device Family pop-up, and then click the Next button.

Figure 6-11. We’re creating a new storyboard, using the View template in the User Interface section

When prompted for a file name, type Main.storyboard. Just as you did earlier, you should choose the View Switcher folder as the save location next to the Where pop-up menu. Make sure that View Switcher is selected from the Group pop-up menu and that the View Switcher target is checked, and then click Create. You’ll know you succeeded when the file Main.storyboard appears in the View Switcher group in the project navigator.

After you’ve done that, you have all the files you need. It’s time to start hooking everything together. The first step in doing so is letting Xcode know that it should use the storyboard you just created as the starting point from which it should bootstrap the app’s GUI. To do this, select the uppermost View Switcher item in the project navigator, and then switch to the General tab in the editing area. This brings up a multi-section configuration view. In the Deployment Info section, use the Main Interface pop-up menu to choose Main.storyboard. With that in place, the app will automatically create its initial interface from the contents of the storyboard when it launches. We haven’t gone over this before, but every project we’ve created before this one had the exact same configuration from the start, thanks to Xcode’s Single View Application project template.

Modifying the App Delegate

Our first stop on the multiview express is the application delegate. Single-click the file BIDAppDelegate.m in the project navigator (make sure it’s the app delegate and not BIDSwitchViewController.m) and make the following changes to that file:

- (BOOL)application:(UIApplication *)application

didFinishLaunchingWithOptions:(NSDictionary *)launchOptions

{

self.window = [[UIWindow alloc] initWithFrame:

[[UIScreen mainScreen] bounds]];

// Override point for customization after application launch.

self.window.backgroundColor = [UIColor whiteColor];

[self.window makeKeyAndVisible];

return YES;

}

What you want to do is delete the lines shown with a line drawn through them. In a completely empty application like the one we started off with, it’s necessary to manually create the application window in code. Since we’re going to load our GUI from the storyboard, that code is unnecessary and can be deleted.

Modifying BIDSwitchViewController.m

Because we’re going to be setting up an instance of BIDSwitchViewController in Main.storyboard, now is the time to add any needed outlets or actions to the BIDSwitchViewController.m file.

We’ll need one action method to toggle between the blue and yellow views. We won’t create any outlets, but we will need two other pointers: one to each of the view controllers that we’ll be swapping in and out. These don’t need to be outlets because we’re going to create them in code rather than in the storyboard. Add the following code to the upper part of BIDSwitchViewController.m:

#import "BIDSwitchViewController.h"

#import "BIDYellowViewController.h"

#import "BIDBlueViewController.h"

@interface BIDSwitchViewController ()

@property (strong, nonatomic) BIDYellowViewController *yellowViewController;

@property (strong, nonatomic) BIDBlueViewController *blueViewController;

@end

Next, add the following empty action method toward the end of the file, just before the final @end line:

- (IBAction)switchViews:(id)sender

{

}

@end

In the past, we’ve added action methods directly within Interface Builder, but here you’ll see that we can work the other way around just as well, since IB can see what outlets and actions are already defined in our source code. Now that we’ve declared the action we need, we can set this controller up in our storyboard.

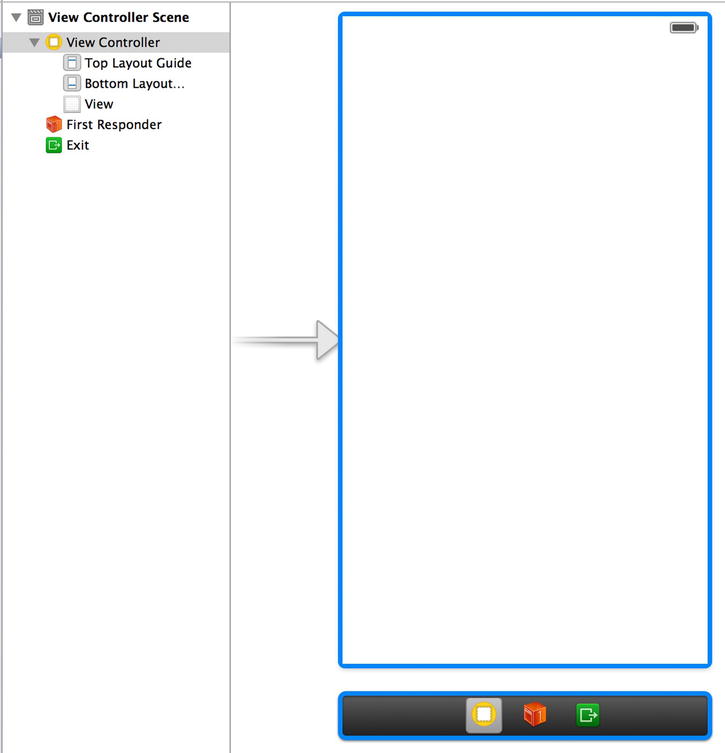

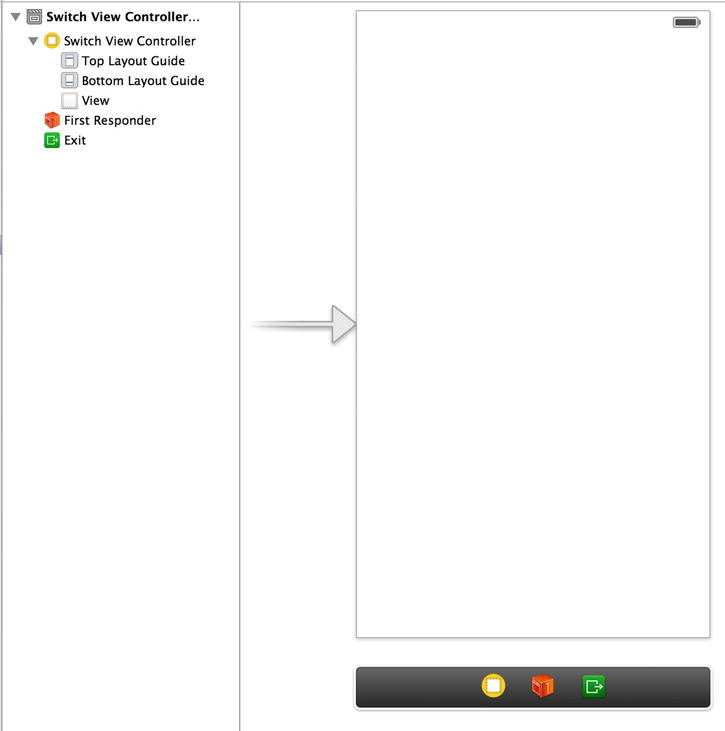

Save your source code and click Main.storyboard to edit the GUI for this app.You’ll see a completely blank editing area, with no views or controllers in sight. Use the object library to find a View Controller and drag it into the editing area. You’ll now see the familiar view of an iPhone-sized rectangle with a row of icons below it.

Figure 6-12. Main.storyboard, showing the first scene this app will use

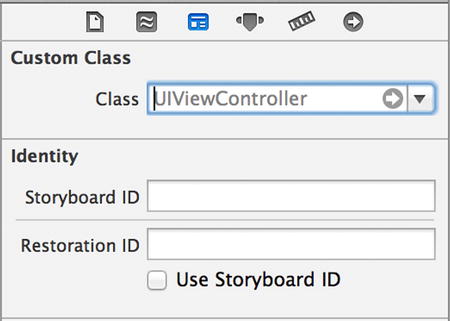

By default, the view controller in this scene is configured to be an instance of UIViewController. We’ll need to change that to BIDSwitchViewController so that Interface Builder allows us to build connections to the BIDSwitchViewController outlets and actions. Single-click the View Controller icon at the bottom of the scene and press ![]()

![]() 3 to open the identity inspector (see Figure 6-13).

3 to open the identity inspector (see Figure 6-13).

Figure 6-13. Notice that the Custom Class field is currently set to UIViewController in the identity inspector. We’re about to change that to BIDSwitchViewController

The identity inspector allows you to specify the class of the currently selected object. Our view controller is currently specified as a UIViewController, and it has no actions defined. Click inside the combo box labeled Class in the Custom Class section, which is at the top of the inspector and currently reads UIViewController. Change this to BIDSwitchViewController.

Once you make that change, press ![]()

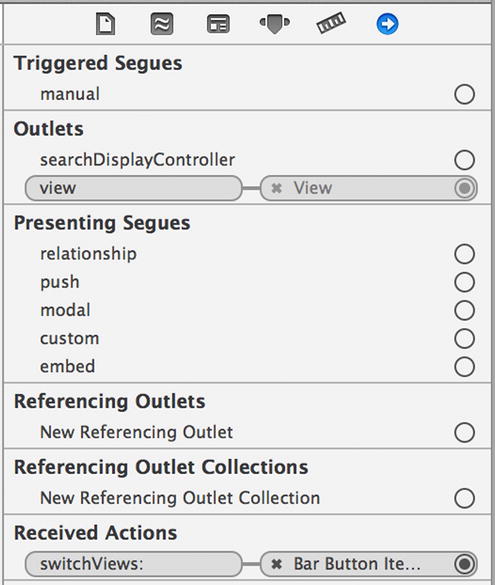

![]() 6 to switch to the connections inspector, where you will see that the switchViews: action method now appears in the section labeled Received Actions (see Figure 6-14). The connection inspector’s Received Actions section shows all the actions defined for the current class. When we changed our view controller to a BIDSwitchViewController, the BIDSwitchViewController action switchViews: became available for connection. You'll see how to use this action in the next section.

6 to switch to the connections inspector, where you will see that the switchViews: action method now appears in the section labeled Received Actions (see Figure 6-14). The connection inspector’s Received Actions section shows all the actions defined for the current class. When we changed our view controller to a BIDSwitchViewController, the BIDSwitchViewController action switchViews: became available for connection. You'll see how to use this action in the next section.

Figure 6-14. The connections inspector showing that the switchViews: action has been added to the Received Actions section

Caution If you don’t see the switchViews: action as shown in Figure 6-14, check the spelling of your class file names. If you don’t get the name exactly right, things won’t match up. Watch your spelling!

Save your storyboard and move to the next step.

Building a View with a Toolbar

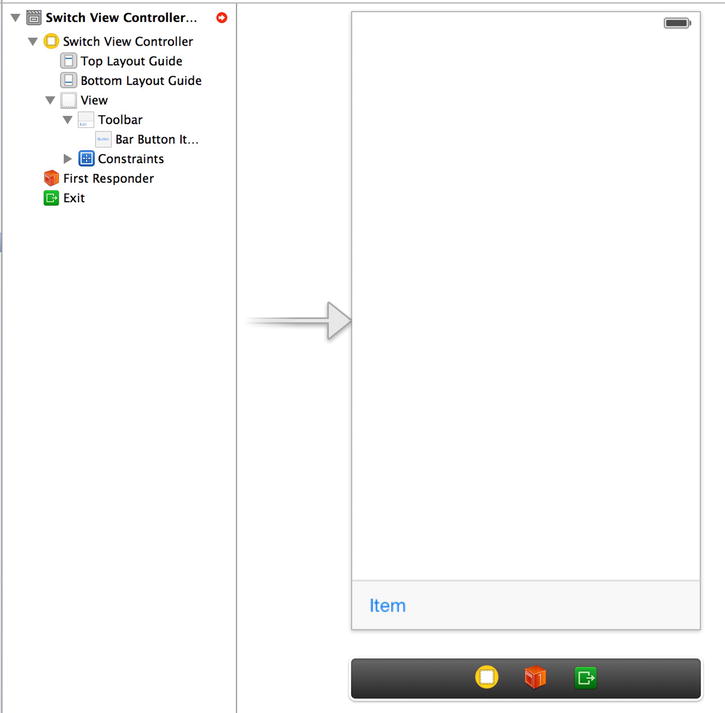

We now need to set up the view for BIDSwitchViewController. As a reminder, this new view controller will be our root view controller—the controller that is in play when our application is launched. BIDSwitchViewController’s content view will consist of a toolbar that occupies the bottom of the screen. Its job is to switch between the blue view and the yellow view, so it will need a way for the user to change the views. For that, we’re going to use a toolbar with a button. Let’s build the toolbar view now.

In the IB editor view, click the view for the scene you just added. The view is an instance of UIView, and as you can see in Figure 6-15, it’s currently empty and quite dull. This is where we’ll start building our GUI.

Figure 6-15. The new empty view contained within our storyboard, just waiting to be filled with interesting stuff

Now, let’s add a toolbar to the bottom of the view. Grab a Toolbar from the library, drag it onto your view, and place it at the bottom, so that it looks like Figure 6-16. We want to keep this toolbar at the bottom of the view no matter what size the view has. To do so, select Editor ![]() Pin

Pin ![]() Bottom Space to Superview. This creates a constraint that makes that happen.

Bottom Space to Superview. This creates a constraint that makes that happen.

Figure 6-16. We dragged a toolbar onto our view. Notice that the toolbar features a single button, labeled Item

Now, to make sure you’re on the right track, click the Run button to make this app launch in the iOS Simulator. You should see a plain white app start up, with a pale gray toolbar at the bottom containing a lone button. If not, go back and retrace your steps to see what you missed.

The toolbar features a single button. We’ll use that button to let the user switch between the different content views. Double-click the button and change its title to Switch Views. Press the Return key to commit your change.

Now we can link the toolbar button to our action method. Before doing that, though, you should be aware that toolbar buttons aren’t like other iOS controls. They support only a single target action, and they trigger that action only at one well-defined moment—the equivalent of a touch up inside event on other iOS controls.

Selecting a toolbar button in Interface Builder can be tricky. Click the view so we are all starting in the same place. Now single-click the toolbar button. Notice that this selects the toolbar, not the button. Click the button a second time. This should select the button itself. You can confirm you have the button selected by switching to the object attributes inspector (![]()

![]() 4) and making sure the top group name is Bar Button Item.

4) and making sure the top group name is Bar Button Item.

Once you have the Switch Views button selected, control-drag from it over to the Switch View Controller icon at the bottom of the scene, and select the switchViews: action. If the switchViews: action doesn’t pop up, and instead you see an outlet called delegate, you’ve most likely control-dragged from the toolbar rather than the button. To fix it, just make sure you have the button rather than the toolbar selected, and then redo your control-drag.

Tip Remember that you can always view the document outline by clicking the button in the lower-left corner of IB’s editor area or by selecting Editor ![]() Show Document Outline from the menu. In the document outline, you can use the disclosure triangles to drill down through the hierarchy to get to any element in the view hierarchy.

Show Document Outline from the menu. In the document outline, you can use the disclosure triangles to drill down through the hierarchy to get to any element in the view hierarchy.

We have one more thing to point out in this scene, which is BIDSwitchViewController’s view outlet. This outlet is already connected to the view in the scene. The view outlet is inherited from the parent class, UIViewController and gives the controller access to the view it controls. When we dragged out a View Controller scene from the object library, IB created both the controller and the view, and hooked them up for us. Nice.

That’s all we need to do here, so save your work. Next, let’s get started implementing BIDSwitchViewController.

Writing the Root View Controller

It’s time to write our root view controller. Its job is to switch between the blue view and the yellow view whenever the user clicks the Switch Views button.

In the project navigator, select BIDSwitchViewController.m and modify the viewDidLoad method to set some things up by adding the lines shown here in bold:

- (void)viewDidLoad

{

[super viewDidLoad];

// Do any additional setup after loading the view.

self.blueViewController = [self.storyboard

instantiateViewControllerWithIdentifier:

@"Blue"];

[self.view insertSubview:self.blueViewController.view atIndex:0];

}

Now fill in the switchViews: method you created earlier by adding the cold shown in bold:

- (IBAction)switchViews:(id)sender

{

if (!self.yellowViewController.view.superview) {

if (!self.yellowViewController) {

self.yellowViewController = [self.storyboard

instantiateViewControllerWithIdentifier:@"Yellow"];

}

[self.blueViewController.view removeFromSuperview];

[self.view insertSubview:self.yellowViewController.view atIndex:0];

} else {

if (!self.blueViewController) {

self.blueViewController = [self.storyboard

instantiateViewControllerWithIdentifier:@"Blue"];

}

[self.yellowViewController.view removeFromSuperview];

[self.view insertSubview:self.blueViewController.view atIndex:0];

}

}

Also, add this code to the existing didReceiveMemoryWarning method:

- (void)didReceiveMemoryWarning {

[super didReceiveMemoryWarning];

// Dispose of any resources that can be recreated.

if (!self.blueViewController.view.superview) {

self.blueViewController = nil;

} else {

self.yellowViewController = nil;

}

}

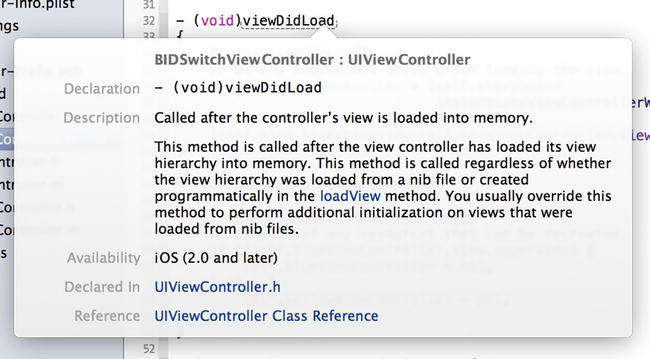

The first method we modified, viewDidLoad, overrides a UIViewController method that is called when the storyboard is loaded. How could we tell? Hold down the ![]() key (the Option key) and single-click the method name viewDidLoad. A documentation pop-up window will appear (see Figure 6-17). Alternatively, you can select View

key (the Option key) and single-click the method name viewDidLoad. A documentation pop-up window will appear (see Figure 6-17). Alternatively, you can select View ![]() Utilities

Utilities ![]() Show Quick Help Inspector to view similar information in the Quick Help panel. viewDidLoad is defined in our superclass, UIViewController, and is intended to be overridden by classes that need to be notified when the view has finished loading.

Show Quick Help Inspector to view similar information in the Quick Help panel. viewDidLoad is defined in our superclass, UIViewController, and is intended to be overridden by classes that need to be notified when the view has finished loading.

Figure 6-17. This documentation window appears when you option-click the viewDidLoad method name

This version of viewDidLoad creates an instance of BIDBlueViewController. We use the instantiateViewControllerWithIdentifier: method to load the BIDBlueViewController instance from the same storyboard that contains our root view controller. To access a particular view controller from a storyboard, we use a string as an identifier—in this case “Blue” —which we’ll set up when we configure our storyboard a little more. Once the BIDBlueViewController is created, we assign this new instance to our blueViewController property:

self.blueViewController = [self.storyboard

instantiateViewControllerWithIdentifier:@"Blue"];

Next, we insert the blue view as a subview of the root view. We insert it at index zero, which tells iOS to put this view behind everything else. Sending the view to the back ensures that the toolbar we created in Interface Builder a moment ago will always be visible on the screen, since we’re inserting the content views behind it:

[self.view insertSubview:self.blueViewController.view atIndex:0];

Now, why didn’t we load the yellow view here also? We’re going to need to load it at some point, so why not do it now? Good question. The answer is that the user may never tap the Switch Views button. The user might just use the view that’s visible when the application launches, and then quit. In that case, why use resources to load the yellow view and its controller?

Instead, we’ll load the yellow view the first time we actually need it. This is called lazy loading, and it’s a standard way of keeping memory overhead down. The actual loading of the yellow view happens in the switchViews: method, so let’s take a look at that.

switchViews: first checks which view is being swapped in by seeing whether yellowViewController’s view’s superview is nil. This will return true if one of two things is true:

- If yellowViewController exists but its view is not being shown to the user, that view will not have a superview because it’s not presently in the view hierarchy, and the expression will evaluate to true.

- If yellowViewController doesn’t exist because it hasn’t been created yet or was flushed from memory, it will also return true.

We then check to see whether yellowViewController exists:

if (!self.yellowViewController.view.superview) {

If it’s a nil pointer, that means there is no instance of yellowViewController, and we need to create one. This could happen because it’s the first time the button has been pressed or because the system ran low on memory and it was flushed. In this case, we need to create an instance of BIDYellowViewController, as we did for the BIDBlueViewController in the viewDidLoad method:

if (!self.yellowViewController) {

self.yellowViewController = [self.storyboard

instantiateViewControllerWithIdentifier:@"Yellow"];

}

At this point, we know that we have a yellowViewController instance because either we already had one or we just created it. We then remove blueViewController’s view from the view hierarchy and add the yellowViewController’s view:

[self.blueViewController.view removeFromSuperview];

[self.view insertSubview:self.yellowViewController.view atIndex:0];

If self.yellowViewController.view.superview is not nil, then we need to do the same thing, but for blueViewController. Although we create an instance of BIDBlueViewController in viewDidLoad, it is still possible that the instance has been flushed because memory got low. Now, in this application, the chances of memory running out are slim, but we’re still going to be good memory citizens and make sure we have an instance before proceeding:

} else {

if (!self.blueViewController) {

self.blueViewController = [self.storyboard

instantiateViewControllerWithIdentifier:@"Blue"];

}

[self.yellowViewController.view removeFromSuperview];

[self.view insertSubview:self.blueViewController.view atIndex:0];

}

In addition to not using resources for the yellow view and controller if the Switch Views button is never tapped, lazy loading also gives us the ability to release whichever view is not being shown to free up its memory. iOS will call the UIViewController method didReceiveMemoryWarning, which is inherited by every view controller, when memory drops below a system-determined level.

Since we know that either view will be reloaded the next time it is shown to the user, we can safely release either controller. We do this by adding a few lines to the existing didReceiveMemoryWarning method:

- (void)didReceiveMemoryWarning {

[super didReceiveMemoryWarning];

// Release any cached data, images, etc, that aren't in use

if (!self.blueViewController.view.superview) {

self.blueViewController = nil;

} else {

self.yellowViewController = nil;

}

}

This newly added code checks to see which view is currently being shown to the user and releases the controller for the other view by assigning nil to its property. This will cause the controller, along with the view it controls, to be deallocated, freeing up its memory.

Tip Lazy loading is a key component of resource management on iOS, and you should implement it anywhere you can. In a complex, multiview application, being responsible and flushing unused objects from memory can be the difference between an application that works well and one that crashes periodically because it runs out of memory.

Implementing the Content Views

The two content views that we are creating in this application are extremely simple. They each have one action method that is triggered by a button, and neither one needs any outlets. The two views are also nearly identical. In fact, they are so similar that they could have been represented by the same class. We chose to make them two separate classes because that’s how most multiview applications are constructed.

The two action methods we’re going to implement do nothing more than show an alert (as we did in Chapter 4’s Control Fun application), so go ahead and add this code to BIDBlueViewController.m:

#import "BIDBlueViewController.h"

@implementation BIDBlueViewController

- (IBAction)blueButtonPressed {

UIAlertView *alert = [[UIAlertView alloc]

initWithTitle:@"Blue View Button Pressed"

message:@"You pressed the button on the blue view"

delegate:nil

cancelButtonTitle:@"Yep, I did."

otherButtonTitles:nil];

[alert show];

}

...

Save the file. Next, switch over to BIDYellowViewController.m and add this very similar code to that file:

#import "BIDYellowViewController.h"

@implementation BIDYellowViewController

- (IBAction)yellowButtonPressed {

UIAlertView *alert = [[UIAlertView alloc]

initWithTitle:@"Yellow View Button Pressed"

message:@"You pressed the button on the yellow view"

delegate:nil

cancelButtonTitle:@"Yep, I did."

otherButtonTitles:nil];

[alert show];

}

Save this file, as well.

Next, select Main.storyboard to open it in Interface Builder, so we can make a few changes. First, we need to add a new scene for BIDBlueViewController. Up until now, each storyboard we’ve dealt with contained just a single controller-view pairing, but the storyboard has more tricks up its sleeve, and holding multiple scenes is one of them. From the object library, drag out another View Controller and drop it in the editing area next to the existing one. Now your storyboard has two scenes, each of which can be loaded dynamically and independently while your application is running. In the row of icons at the bottom of the new scene, single-click the View Controller icon and press ![]()

![]() 3 to bring up the identity inspector. In the Custom Class section, Class defaults to UIViewController; change it to BIDBlueViewController.

3 to bring up the identity inspector. In the Custom Class section, Class defaults to UIViewController; change it to BIDBlueViewController.

We also need to create an identifier for this new view controller, so that our code can find it inside the storyboard. Just below the Custom Class in the identity inspector, you’ll see a Storyboard ID field. Click there and type Blue to match what we used in our code.

So now you have two scenes. We showed you earlier how to configure your app to load this storyboard at launch time, but we didn’t mention anything about scenes there. How will the app know which of these two views to show? The answer lies in the big arrow pointing at the first scene, as shown in Figure 6-18. That arrow points out the storyboard’s default scene, which is what the app shows when it starts up. If you want to choose a different default scene, all you have to do is drag the arrow to point at the scene you want.

Figure 6-18. We just added a second scene to our storyboard. The big arrow points at the default scene

Single-click the big rectangular view in the new scene you just added, and then press ![]()

![]() 4 to bring up the object attributes inspector. In the inspector’s View section, click the color well that’s labeled Background, and use the pop-up color picker to change the background color of this view to a nice shade of blue. Once you are happy with your blue, close the color picker.

4 to bring up the object attributes inspector. In the inspector’s View section, click the color well that’s labeled Background, and use the pop-up color picker to change the background color of this view to a nice shade of blue. Once you are happy with your blue, close the color picker.

Drag a Button from the library over to the view, using the guidelines to center the button in the view, both vertically and horizontally. We want to make sure that the button stays centered no matter what, so make two constraints to that effect. First select Editor ![]() Align

Align ![]() Horizontal Center in Container from the menu. Then click the new button again, and select Editor

Horizontal Center in Container from the menu. Then click the new button again, and select Editor ![]() Align

Align ![]() Vertical Center in Container from the menu.

Vertical Center in Container from the menu.

Double-click the button and change its title to Press Me. Next, with the button still selected, switch to the connections inspector (by pressing ![]()

![]() 6), drag from the Touch Up Inside event to the File’s Owner icon, and connect to the blueButtonPressed action method. You’ll notice that the text of the button is a blue color by default. Since our background is also blue, there’s a pretty big risk that this button’s text will be hard to see! Switch to the attributes inspector with

6), drag from the Touch Up Inside event to the File’s Owner icon, and connect to the blueButtonPressed action method. You’ll notice that the text of the button is a blue color by default. Since our background is also blue, there’s a pretty big risk that this button’s text will be hard to see! Switch to the attributes inspector with ![]()

![]() 4, and then use the combined color-picker/pop-up button to change the Text Color value to something else. Depending on how dark your background color is, you might want to choose either white or black.

4, and then use the combined color-picker/pop-up button to change the Text Color value to something else. Depending on how dark your background color is, you might want to choose either white or black.

Now it’s time to do pretty much the same set of things for BIDYellowViewController. Grab yet another View Controller from the object library and drag it into the editor area. Don’t worry if things are getting crowded; you can stack those scenes on top of each other, and no one will mind! Click the View Controller icon in the dock and use the identity inspector to change its class to BIDYellowViewController and its Storyboard ID to Yellow.

Next, select the view and switch to the object attributes inspector. There, click the Background color well, select a bright yellow, and then close the color picker.

Next, drag out a Button from the library and use the guidelines to center it in the view. Use the menu actions to create constraints aligning its horizontal and vertical center, just like for the last button. Now change its title to Press Me, Too. With the button still selected, use the connections inspector to drag from the Touch Up Inside event to the View Controller icon, and connect to the yellowButtonPressed action method.

When you’re finished, save the storyboard and get ready to take this bad boy for a spin. Hit the Run button in Xcode, and your app should start up and present you with a full screen of blue.

When our application launches, it shows the blue view we built. When you tap the Switch Views button, it will change to show the yellow view that we built. Tap it again, and it goes back to the blue view. If you tap the button centered on the blue or yellow view, you’ll get an alert view with a message indicating which button was pressed. This alert shows that the correct controller class is being called for the view that is being shown.

The transition between the two views is kind of abrupt, though. Gosh, if only there were some way to make the transition look nicer.

Of course, there is a way to make the transition look nicer! We can animate the transition to give the user visual feedback of the change.

UIView has several class methods we can call to indicate that the transition between views should be animated, to indicate the type of transition that should be used, and to specify how long the transition should take.

Go back to BIDSwitchViewController.m and enhance your switchViews: method by adding the lines shown here in bold:

- (IBAction)switchViews:(id)sender

{

[UIView beginAnimations:@"View Flip" context:NULL];

[UIView setAnimationDuration:0.4];

[UIView setAnimationCurve:UIViewAnimationCurveEaseInOut];

if (!self.yellowViewController.view.superview) {

if (!self.yellowViewController) {

self.yellowViewController = [self.storyboard

instantiateViewControllerWithIdentifier:@"Yellow"];

}

[UIView setAnimationTransition:UIViewAnimationTransitionFlipFromRight

forView:self.view cache:YES];

[self.blueViewController.view removeFromSuperview];

[self.view insertSubview:self.yellowViewController.view atIndex:0];

} else {

if (!self.blueViewController) {

self.blueViewController = [self.storyboard

instantiateViewControllerWithIdentifier:@"Blue"];

}

[UIView setAnimationTransition:UIViewAnimationTransitionFlipFromLeft

forView:self.view cache:YES];

[self.yellowViewController.view removeFromSuperview];

[self.view insertSubview:self.blueViewController.view atIndex:0];

}

[UIView commitAnimations];

}

Compile this new version and run your application. When you tap the Switch Views button, instead of the new view just snapping into place, the old view will flip over to reveal the new view, as shown in Figure 6-19.

Figure 6-19. One view transitioning to another, using the flip style of animation

To tell iOS that we want a change animated, we need to declare an animation block and specify how long the animation should take. Animation blocks are declared by using the UIView class method beginAnimations:context:, like so:

[UIView beginAnimations:@"View Flip" context:NULL];

[UIView setAnimationDuration:0.4];

beginAnimations:context: takes two parameters. The first is an animation block title. This title comes into play only if you take more direct advantage of Core Animation, the framework behind this animation. For our purposes, we could have used nil. The second parameter is a (void *) that allows you to specify an object (or any other C data type) whose pointer you would like associated with this animation block. We used NULL here, since we don’t need to do that. We also set the duration of the animation, which tells UIView how long (in seconds) the animation should last.

After that, we set the animation curve, which determines the timing of the animation. The default, which is a linear curve, causes the animation to happen at a constant speed. The option we set here, UIViewAnimationCurveEaseInOut, specifies that the animation should start slow but speed up in the middle, and then slow down again at the end. This gives the animation a more natural, less mechanical appearance:

[UIView setAnimationCurve:UIViewAnimationCurveEaseInOut];

Next, we need to specify the transition to use. At the time of this writing, four iOS view transitions are available:

- UIViewAnimationTransitionFlipFromLeft

- UIViewAnimationTransitionFlipFromRight

- UIViewAnimationTransitionCurlUp

- UIViewAnimationTransitionCurlDown

We chose to use two different effects, depending on which view was being swapped in. Using a left flip for one transition and a right flip for the other makes the view seem to flip back and forth.

The cache option speeds up drawing by taking a snapshot of the view when the animation begins and using that image, rather than redrawing the view at each step of the animation. You should always cache the animation unless the appearance of the view may need to change during the animation:

[UIView setAnimationTransition:UIViewAnimationTransitionFlipFromRight

forView:self.view cache:YES];

Next, we remove the currently shown view from our controller’s view and instead add the other view.

When we’re finished specifying the changes to be animated, we call commitAnimations on UIView. Everything between the start of the animation block and the call to commitAnimations will be animated together.

Thanks to Cocoa Touch’s use of Core Animation under the hood, we’re able to do fairly sophisticated animation with only a handful of code.

Whoo-boy! Creating our own multiview controller was a lot of work, wasn’t it? You should have a very good grasp on how multiview applications are put together, now that you’ve built one from scratch.

Although Xcode contains project templates for the most common types of multiview applications, you need to understand the overall structure of these types of applications, so you can build them yourself from the ground up. The delivered templates are incredible time-savers; but at times, they simply won’t meet your needs.

In the next few chapters, we’re going to continue building multiview applications to reinforce the concepts from this chapter and to give you a feel for how more complex applications are put together. In Chapter 7, we’ll construct a tab bar application. Let’s get going!