CHAPTER 18

Security for Networked AV Applications

In this chapter, you will learn about

• Documenting security objectives

• Evaluating a client’s security posture

• Creating a risk register for an AV/IT network

• Implementing a risk response for common security risks

Consider how and why you protect your home, whether you use an alarm system or simply lock your doors. You secure your home for the same reason your customers protect their IT networks—to protect the valuables inside. As AV systems migrate to enterprise data networks, user organizations expect them to maintain a security posture in alignment with their overall information security goals. AV designers must understand their clients’ security requirements and take them into account when designing a system.

Every client’s security needs are unique and evolve over time. Like the all-important needs assessment that designers conduct before creating an AV system, there is a process they should follow to ensure they discover clients’ security needs and design a system that meets them.

Security Objectives

As AV systems migrate to enterprise data networks, clients expect those AV systems to be in alignment with their information security goals. In many cases, those goals may be more than just best practices; they may be required for regulatory compliance. Healthcare facilities in the United States must protect data in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Financial institutions in the United States must comply with the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, among others. Industrial companies and others around the world may seek to comply with ISO-27000, a security framework that is now required for all ISO-9000 series-certified companies. To the extent that an AV system interfaces with IT systems or handles data that falls under various compliance frameworks, design and integration choices that put them out of compliance may impede installation.

Even when regulatory compliance isn’t a central concern, most clients have a similar set of security objectives.

• Confidentiality Ensuring that people who shouldn’t have access to information don’t.

• Integrity Ensuring that people who are permitted to access information can trust that the information has not been changed or altered.

• Availability Ensuring that access to information is unimpeded. This extends to any type of information, including multimedia, video sources, and more.

Think of these objectives as the CIA triad. No security system is perfect, and each organization weighs these objectives differently. Some companies can trade off tighter security measures for easier access to files. Others can tolerate downtime if it means keeping their data secure. Typically, as you communicate with clients, you may find that two of the three legs of the CIA triad are most important.

Any technology that is connected to an enterprise network could potentially impact one or more of these security objectives. As an AV designer, you are not likely to specify or configure firewalls, intrusion detection devices, or other network security technologies. Your job is to be aware of a client’s security requirements, communicate that information to the AV team, and, where possible, address and mitigate security risk in your AV design.

Perhaps the most important aspect of discovering security objectives and requirements, regardless of how extensive they may be, is documenting them. During any security needs analysis, designers should document everything they can about security and risk. When planning a project, allocate more time than you think necessary to document security requirements, issues, and strategies. You’ll be glad you did.

Identifying Security Requirements

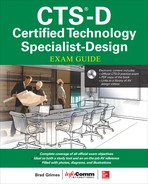

A recurring issue in the AV industry—and an impediment to getting paid—is that security requirements are often discovered during installation or commissioning. There is nothing worse than performing your final systems verification, expecting final sign-off, and finding there’s a security requirement you didn’t know about, rendering the project unacceptable. Therefore, it’s critical to identify security requirements and set expectations up front, before the client signs off on the initial design (see Figure 18-1). This will give you time to communicate the requirements and, if necessary, submit change orders to ensure equipment is specified that can support those requirements. You may also need to budget cost and time to complete International Organization for Standardization (ISO) surveys and risk mitigation plans.

Figure 18-1 Ideally, you should identify security requirements upfront. Typically, AV pros wait too late.

If possible, move the identification of security requirements into the needs analysis phase of the AV design. This may not always be possible; a company may not want to expose its security profile or requirements to just anyone who bids. But you can at least begin to understand what compliance frameworks the client operates under and which legs of the CIA triad are priorities.

At a minimum, designers should identify security requirements and address them in the design prior to sign-off. This is usually the last time in the process when it is reasonably easy to make changes without impacting schedules or equipment costs.

Security requirements and the steps needed to meet them should be appended to the statement of work and listed as system sign-off criteria. This is to protect both the client and the AV designer/integrator.

Determining a Security Posture

AV systems help facilitate communication, but they can also create vulnerabilities in your client’s system. The client’s security posture may limit what equipment can be in an AV installation. For example, some customers may forbid the use of wireless microphones because their signals can be intercepted. Other customers may not allow you to use a projector with nonvolatile memory (NVM) for fear that images could be retrieved from the projector if it were stolen.

With respect to networked AV systems, you have to consider whether the AV system provides a way to access the rest of the network or any other information the customer wants to protect. Can you guarantee that a hacker can’t use the digital signage outside the boardroom to access the chief executive officer’s (CEO’s) schedule or use the videoconferencing system to spy on confidential meetings? You need to understand the elements of a security posture that are relevant to your AV design.

A security posture describes what an organization is trying to protect and how vigorously it needs to protect it. When it comes to AV systems, the security posture should be set by the client. AV designers don’t create security postures; they make their systems compliant with an existing posture.

Security postures will likely be unique to each job because each customer will have different requirements. You might hear security postures described as lax, realistic, or paranoid. Security postures are often influenced by external oversight, such as an industry or regulatory authority that sets security standards, or internal operations, such as a company security policy.

There are several steps to determining a security posture.

• Learn the client’s mission. The AV system you’re designing should help achieve an organization’s mission. Knowing the vision or goals of the organization will help you see the value of the AV system from the client’s perspective and prioritize which aspects the client needs to secure.

• Learn the concept of operations. The concept of operations describes how the client fulfills its mission. How does the organization function? How will the AV system help the organization function better? Examine its current security processes and procedures. Can any of them be applied to the AV system? Will any of them have to change?

• Assess the data’s importance. Specifically, this concerns data traveling through the AV system. Where does the information in your AV system fit into the organization’s mission and concept of operations? Is the AV system essential to operations, or does it simply carry casual information among departments? Is there an existing system that carries similar information that can be used for reference?

• Learn the client’s risk profile. This may involve signing a nondisclosure agreement. A risk profile is how tolerant a customer is of risk. How worried is the customer about security breaches? A customer’s risk profile may vary for different content. What type of intrusions does the customer worry about most? For instance, a university may not care much if an outsider hacks into its streaming video server and watches all the recorded lectures. It may be concerned, however, about protecting the content servers that store footage from its medical research facility. The organization’s security policies will be a reflection of its risk profile.

• Identify stakeholders. This especially includes those with the power to approve and negotiate. The project stakeholders are the best sources of information about security posture. Document the role of each stakeholder so that various members of the project team know whom they can contact to learn different information about security posture. Negotiation is an integral part of the security and risk management process. Within your stakeholders, you will need to identify who has approval authority or negotiation power.

• Identify governance structure. You need to know at least the sections that apply to your AV system, which will probably need to exist within the customer’s IT framework. Because of the complexity of IT systems, mature organizations create control objectives that govern how to run the system. They may adhere to a standardized IT governance structure, such as Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL) or Control Objectives for Information and Related Technology (COBIT). Even if the client doesn’t use a specific standardized governance structure, its IT policies should cover similar categories, including the following:

• How do the systems and processes help the organization meet its mission?

• What are the usage policies, and which best practices does your customer follow?

• Who are your user groups, and will any of them use the system remotely?

• What are the audit guidelines and processes?

• How does the system compare to industry best practices for similar systems?

• How does your customer measure the success of a system?

• Identify project constraints. Constraints include budget, time for completion, and policies that affect the eventual installation. The client’s security policies may impose certain constraints on the project. For example, there may be a policy against using Wi-Fi. In that case, you may only select devices without Wi-Fi or with the capability to disable Wi-Fi. Constraints will likely impose financial burdens on the project. A cost-benefit analysis of those burdens may result in the revision of policies or requirements. For instance, the client might agree that, given the cost of running new cable, a few encrypted Wi-Fi devices are OK after all.

Stakeholder Input

Information security always supports business goals, and not every department in an organization has the same business goals. The amount of time, effort, and cost spent on security depends on those goals. There is no one-size-fits-all, “secure enough” system. Designers need to come to agreement with various parties on what security requirements are important.

Verify that you have input from all relevant stakeholders. Typically, an AV designer/integrator needs to address three areas of security, so it is important to speak to stakeholders with experience in each area.

• Operational These are the stakeholders who own data. They determine what needs to be protected and how vigorously. The other two areas support operational security.

• Network These are the IT stakeholders who specify and administrate network policies. There are generally two types of IT network stakeholders: those responsible for the ports and protocols, firewalls, and routers in a network; and those responsible for access control (see “The Triple-A of Access Control”).

• Physical These are traditional security stakeholders, responsible for physical access to gear, spaces, and more. They can help you create policies on how to secure gear and cabinets to prevent theft.

Here is an example of an AV-specific operational security concern that may not involve network security: Say your client just finished renovating their office building. They have a beautiful conference room on their lobby level with three glass walls. If the CEO displays the company’s three-year financial plan on the conference room videowall, anyone in the lobby could read it. These are the types of security concerns an AV designer must be aware of.

Assessing Risk

Put yourself in this position: You are considering for your design an AV device that supports a bunch of standard network protocols, including Telnet, Secure Shell (SSH), HTTP Secure (HTTPS), Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP), and File Transfer Protocol (FTP). It has a default password of “password” and only one user account named “admin,” which can’t be changed. Here are some potential vulnerabilities:

• HTTP, Telnet, and FTP are clear-text protocols, meaning anyone with access and a simple network analyzer can see exactly what’s going across the wire, including usernames and passwords.

• The default password could be found easily on Google.

• The default username can’t be changed.

• The client can’t set up multiple accounts for nonrepudiation.

• The client can’t set up accounts with different user permissions.

Now you’re in a meeting with representatives of the client. You bring up the possible vulnerabilities of your proposed AV device and engage the client in the question of “Big deal or not a big deal?” What you’re doing is helping identify risk or possible threats to the AV system.

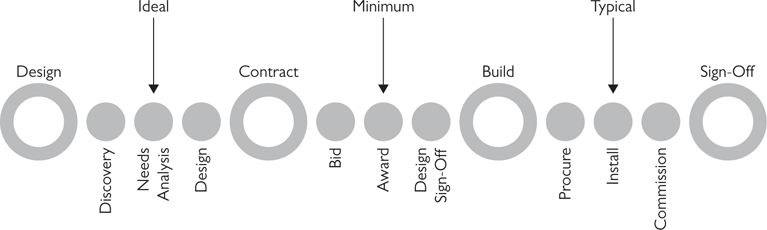

A threat usually requires a vulnerability and someone or something that might want to exploit that vulnerability. In most cases, if there’s a vulnerability, you should assume someone will want to exploit it. Depending on the value of what the client must protect or the ease by which a vulnerability might be exploited, you may determine that a threat is larger or smaller and requires commensurate protective measures.

AV designers should attend risk-response meetings with a list of potential vulnerabilities. This is not necessarily a list of bugs and exploits but rather a list of services and functions handled by AV devices that may need a security policy. Depending on the security posture and any required procedures within the organization, this may be a general list of functions or a list of specific gear.

Risk Registers

Once you’re aware of the threats and risks to an AV system, you should create a risk register. A risk register is a methodology for prioritizing the threats that you can mitigate. It usually takes the form of a comprehensive table or spreadsheet and helps you assign value to risks depending on two factors: probability (how likely something bad will happen) and impact (how bad things will be if it does).

Risk registers are used across all forms of business, not just security. There are many methodologies and templates for assigning risk, and the process can be simple or complex, depending on the details and the client’s security posture. A risk register might include information such as a description of the risk, the type of risk, the likelihood it will occur, the severity of its effects, a current status of the risk, and any internal stakeholders responsible for managing the risk. In general, if your client already has a risk management process or template, use theirs.

A risk register also includes an entry for countermeasures—basically how the risk might be handled. Typically, there are four ways to handle a risk.

• Avoid it. Limit or avert the risky activity.

• Accept it. Because the probability or impact is low enough, the client is willing to take the risk.

• Transfer it. The client can purchase insurance or maintenance plans or adopt cloud-based technology services.

• Mitigate it. Make changes to design, configuration, or operational procedures to lower the probability or impact of a risk to the point where it’s acceptable.

Designers should consult with clients about their options and assign a response to each risk in the risk register.

Mitigation Planning

The most common risk response is mitigation, one of the final steps in a security strategy (see Figure 18-2). A mitigation plan includes the action proposed to mitigate a risk, a contingency (what to do if something bad happens even after you’ve mitigated the risk), the name of someone responsible for the mitigation plan, and a due date.

Figure 18-2 Planning for AV system security involves many steps.

The responsible party and due date will usually come from the client, not the designer/integrator. For example, let’s assume you have a projector that can be controlled only via Telnet. The vulnerability is that Telnet usernames and passwords are sent via clear text and can therefore be discovered and the system accessed. The potential impact is fairly low because the worst thing a hacker could do is turn off a projector. But the probability it will happen is fairly high because of how easy it is to find out the password and break in.

A mitigation plan for this system may be to create an AV-specific virtual LAN (VLAN) for just the projector and the devices that need to talk to it, such as a control system. Then create an access-control list on the router to that VLAN that blocks all Telnet traffic. That way, only a computer or device that is physically connected to that VLAN can see the network traffic and Telnet into the vulnerable projector. Typically, the job of creating the VLAN would be assigned to the client’s network team, with a due date before the installation date.

In general, you may find that segregating AV applications onto separate VLANs is a good mitigation strategy for a variety of situations. In most cases, this is a design-level consideration, rather than a configuration task, so address it early.

The following are some other risk-mitigation strategies.

Change Default Passwords

Default passwords should never be left in a system. This is a huge security risk that is easy to fix. Before integration, change all default passwords to a job-specific password. You can use some standard combination of numbers and job name. For example, 246*InfoComm could be your job password. This gives you a measure of security and makes it easy for project team members to access the system.

After systems verification and commissioning, when you turn over systems documentation to the client, give them a list of devices with usernames, job passwords, and instructions for changing the passwords. That way, they can implement password security that meets their own company policy.

Create Multiple User Roles

If a piece of AV equipment is going to be accessed over the network for day-to-day use—as opposed to just configuration—create separate accounts for users and administrators with only the permissions required to perform their job functions. It’s bad practice to allow anyone who might need to use or schedule an AV system to have configuration rights, too.

Accounts for Every User

The most secure password management strategy is to set an account for every user and then assign individual roles based on their access requirements. The challenge is scalability. What if you have 100 projectors that require two admins and eight users each? And what if the eight users are different based on where each projector is used? And what if somebody quits?

This is where directory servers come in handy. Directory servers are a centralized system used to keep, change, and store passwords. Most clients usually have a directory server for enforcing company password policies on laptops or other computing devices. You can integrate AV systems with an existing directory server for authentication and authorization.

Authentication is the username and password that proves the person requesting access to a system is who they say they are. Authorization takes that identity and matches it to a group membership. By being a member of the group, the person inherits the group’s permissions. Say a member group is called projector admins. If someone wants to administer a projector, the projector authenticates that person and then checks to see whether the person is a member of the projector admin group. If so, the projector grants access.

The following are among the advantages of using a centralized directory:

• It greatly lowers the amount of administration required. You can administer policies for 100 projectors in one place.

• It is much more likely that password policy will be adhered to because users have to change only one password for every device.

• Because you may be able to leverage directory servers that are already in place for IT purposes, you can hand off password policy to the organization.

Keep in mind, however, the ability to use a centralized directory is not universally supported by all AV products.

Disable Unnecessary Services

AV devices tend to be “Swiss army knives,” with many different functions and connection capabilities, which may or may not be used on a given job. Best practice is to disable services such as Telnet, FTP, or HTTP when they are not being used for a particular installation. This gives a potential attacker fewer doors to try to break into.

Enable Encryption and Auditing

Use encryption where possible. This prevents people from reading passwords and potentially compromising data. Use HTTPS instead of HTTP, SSH instead of Telnet, and so on. Then, disable the nonencrypted version.

Plus, any systems that have an audit function, which tracks access and security failures, should be enabled. This offers a record of who logged in when, any failed login attempts, and more. Such an audit report not only can help catch and punish bad guys, but it can also help the client figure out how they got into a system to further mitigate risk down the road.

Chapter Review

AV designers aren’t necessarily in the business of securing their clients’ systems. But it is their job to understand and document clients’ security requirements, recognize threats and vulnerabilities, help assess risk, and offer plans for mitigating or otherwise address risk as part of their designs.

In this chapter, you learned how to identify a client’s security objectives, requirements, and posture. You also learned how to use a risk register not only to describe the possible threats to a client’s information systems but also to plan for ways of addressing those threats. If you come away with nothing else from this chapter, remember always to document everything about a client’s security requirements and how they might be impacted by your AV design. You never want to learn too late that you’ve created an insecure AV system.

Review Questions

The following questions are based on the content covered in this chapter and are intended to help reinforce the knowledge you have assimilated. These questions are not extracted from the CTS-D exam nor are they necessarily CTS-D practice exam questions. For an official CTS-D practice exam, download the Total Tester as described in Appendix D.

1. A client’s security objectives can often be described with respect to the CIA triad. CIA stands for:

A. Central Intelligence Agency

B. Confidentiality, integrity, availability

C. Confidentiality, information, access

D. Communication, infrastructure, authorization

2. Which of the following is not a step in assessing a client’s security posture?

A. Assessing how important the client’s data is

B. Testing the client’s network for vulnerabilities

C. Identifying stakeholders

D. Understanding project constraints

3. When you’ve identified a security risk, you can avoid it, accept it, transfer it, or __________.

A. Eliminate it

B. Change it

C. Mitigate it

D. Reconfigure it

4. Which is an important consideration for AV designers concerning a client’s wireless network?

A. QoS could be minimized.

B. Integration of POS equipment into the system.

C. Data security/encryption issues.

D. Variable bandwidth dynamics issues.

5. Which of the following is a mitigation strategy for addressing security risks introduced by AV systems?

A. Building a firewall

B. Setting all passwords to “password”

C. Hiring a security expert

D. Putting AV systems on a VLAN

Answers

1. B. A client’s security objectives can often be described with respect to confidentiality, integrity, and availability.

2. B. When assessing a client’s security posture, it’s important to assess the importance of the client’s data, identify stakeholders, and understand project constraints. Testing the network for vulnerabilities is not a designer’s job.

3. C. When you’ve identified a security risk, you can avoid it, accept it, transfer it, or mitigate it.

4. C. With respect to a client’s wireless network, AV designers need to consider data security and encryption issues.

5. D. To mitigate security issues introduced by AV systems, consider putting those systems on a virtual LAN (VLAN).