Chapter 6

Getting to grips with consolidated accounts

A group-building exercise

The purpose of consolidated accounts is to present the financial situation of a group of companies as if they formed one single entity. This chapter deals with the basic aspects of consolidation that should be understood by anyone interested in corporate finance.

An analysis of the accounting documents of each individual company belonging to a group does not serve as a very accurate or useful guide to the economic health of the whole group. The accounts of a company reflect the other companies that it controls only through the book value of its shareholdings (revalued or written down, where appropriate) and the size of the dividends that it receives.

The goal of this chapter is to familiarise readers with the problems arising from consolidation. Consequently, we present an example-based guide to the main aspects of consolidation in order to facilitate analysis of consolidated accounts.

Section 6.1 Consolidation methods

Any firm that controls other companies exclusively or that exercises significant influence over them should prepare consolidated accounts and a management report for the group.1

Consolidated accounts must be certified by the statutory auditors and, together with the group’s management report, made available to shareholders, debtholders and all other parties with a vested interest in the company.

Listed European companies have been required to use IFRS2 accounting principles for their consolidated financial statements since 2005 and groups from most other countries have been required or allowed to use these accounting standards since then.

The companies to be included in the preparation of consolidated accounts form what is known as the scope of consolidation. The scope of consolidation comprises:

- the parent company;

- the companies in which the parent company has a material influence (which is assumed when the parent company holds at least 20% of the voting rights).

However, a subsidiary should not be consolidated when its parent loses the power to govern its financial and operating policies, for example when the subsidiary becomes subject to the control of a government, a court or an administration. Such subsidiaries should be accounted for at fair market value.

For instance, let us consider a company with a subsidiary that appears on its balance sheet with an amount of 20. Consolidation entails replacing the historical cost of 20 with all or some of the assets, liabilities and equity of the company being consolidated.

There are two methods of consolidation which are used, depending on the strength of the parent company’s control or influence over its subsidiary:

| Type of relationship | Type of company | Consolidation method |

| Control | Subsidiary | Full consolidation3 |

| Significant influence | Associate | Equity method |

We will now examine each of these two methods in terms of its impact on sales, net profit and shareholders’ equity.

1. Full consolidation

The accounts of a subsidiary are fully consolidated if the latter is controlled by its parent. Control is defined as the ability to direct the strategic financing and operating policies of an entity so as to access benefits. It is presumed to exist when the parent company:

- holds, directly or indirectly, over 50% of the voting rights in its subsidiary;

- holds, directly or indirectly, less than 50% of the voting rights but has power over more than 50% of the voting rights by virtue of an agreement with other investors;

- has power to govern the financial and operating policies of the subsidiary under a statute or an agreement;

- has power to cast the majority of votes at meetings of the board of directors; or

- has power to appoint or remove the majority of the members of the board.

The criterion of exclusive control is the key factor under IFRS standards. It can encompass companies in which only a minority is held (or even no shares at all!) provided the subsidiary is deemed to be controlled by the parent company.

As its name suggests, full consolidation consists of transferring all the subsidiary’s assets, liabilities and equity to the parent company’s balance sheet and all the revenues and costs to the parent company’s income statement.

The assets, liabilities and equity thus replace the investments held by the parent company, which therefore disappear from its balance sheet.

That said, when the subsidiary is not controlled exclusively by the parent company, the claims of the other “minority” shareholders on the subsidiary’s equity and net income also need to be shown on the consolidated balance sheet and income statement of the group.

Assuming there is no difference between the book value of the parent’s investment in the subsidiary and the share of the book value of the subsidiary’s equity,4 full consolidation works as follows.

- On the balance sheet:

- the subsidiary’s assets and liabilities are added item by item to the parent company’s balance sheet;

- the historical cost amount of the shares in the consolidated subsidiary held by the parent is eliminated from the parent company’s balance sheet and the same amount is deducted from the parent company’s reserves;

- the subsidiary’s equity (including net income) is then added to the parent company’s equity and then allocated between the interests of the parent company (added to its reserves) and those of minority investors in the subsidiary (if the parent company does not hold 100% of the capital), which is added to a special minority interests line below the line item showing the parent company’s shareholders’ equity.

- On the income statement, all the subsidiary’s revenues and charges are added item by item to the parent company’s income statement. The parent company’s net income is then broken down into:

- the portion attributable to the parent company, which is added to the parent company’s net income on both the income statement and the balance sheet, to create the line net income attributable to shareholders or group share net income;

- the portion attributable to third-party investors, which is shown on a separate line of the income statement under the heading “minority interests”.

From a solvency standpoint, minority interests certainly represent shareholders’ equity. But from a valuation standpoint, they add no value to the group since minority interests represent shareholders’ equity and net profit attributable to third parties and not to shareholders of the parent company.

Right up until the penultimate line of the income statement, financial analysis assumes that the parent company owns 100% of the subsidiary’s assets and liabilities and implicitly that all the liabilities finance all the assets. This is true from an economic, but not from a legal, perspective.

To illustrate the full consolidation method, consider the following example assuming that the parent company owns 75% of the subsidiary company.

The original balance sheets are as follows:

| Parent company’s balance sheet | Subsidiary’s balance sheet | ||||||

| Investment in the subsidiary5 | 15 | Shareholders’ equity | 70 | Assets | 28 | Shareholders’ equity | 20 |

| Other assets | 57 | Liabilities | 2 | Liabilities | 8 | ||

In this scenario, the consolidated balance sheet would be as follows:

| Consolidated balance sheet | |||

| Investment in the subsidiary (15 − 15) | 0 | Shareholders’ equity (70 + 20 − 15) | 75 |

| Assets (57 + 28) | 85 | Liabilities (2 + 8) | 10 |

Or, in an alternative form:

| Consolidated balance sheet | |||

| Assets | 85 | Shareholders’ equity group share (75 − 5) | 70 |

| Minority interests (20 × 25%) | 5 | ||

| Liabilities | 10 | ||

Group assets and liabilities thus correspond to the sum of the assets and liabilities of the parent company and those of its subsidiary. Group equity is equal to the equity of the parent company increased by the share of the subsidiary’s net income not paid out as dividends since the parent company started consolidating this subsidiary. Minority interests correspond to the share of minority shareholders in the equity and net income of the subsidiary.

The original income statements are as follows:

| Parent company’s income statement | Subsidiary’s income statement | ||||||

| Costs | 80 | Net sales | 100 | Costs | 30 | Net sales | 38 |

| Net income | 20 | Net income | 8 | ||||

In this scenario, the consolidated income statement would be as follows:

| Consolidated income statement | |||

| Costs (80 + 30) | 110 | Net sales (100 + 38) | 138 |

| Net income (20 + 8) | 28 | ||

Or, in a more detailed form:

| Consolidated income statement | |||

| Costs | 110 | Net sales | 138 |

| Net income: | |||

| Group share | 26 | ||

| Minority interest (8 × 25%) | 2 | ||

2. Equity method of accounting

When the parent company exercises significant influence over the operating and financial policy of its associate, the latter is accounted for under the equity method. Significant influence over the operating and financial policy of a company is assumed when the parent holds, directly or indirectly, at least 20% of the voting rights. Significant influence may be reflected by participation on the executive and supervisory bodies, participation in strategic decisions, the existence of major intercompany links, exchanges of management personnel and a relationship of dependence from a technical standpoint.

Most companies that were consolidated under the proportionate method are now consolidated under the equity method, since the former method has been banned by IFRS.

Equity accounting consists of replacing the carrying amount of the shares held in an associate (also known as an equity affiliate or associated undertaking) with the corresponding portion of the associate’s shareholders’ equity (including net income).

This method is purely financial. Both the group’s investments and aggregate profit are thus reassessed on an annual basis. Accordingly, the IASB regards equity accounting as being more of a valuation method than a method of consolidation.

From a technical standpoint, equity accounting takes place as follows:

- the historical cost amount of shares held in the associate is subtracted from the parent company’s investments and replaced by the share attributable to the parent company in the associate’s shareholders’ equity including net income for the year;

- the carrying value of the associate’s shares is subtracted from the parent company’s reserves, to which is added the share in the associate’s shareholders’ equity, excluding the associate’s income attributable to the parent company;

- the portion of the associate’s net income attributable to the parent company is added to its net income on the balance sheet and the income statement.

The equity method of accounting therefore leads to an increase each year in the carrying amount of the shareholding on the consolidated balance sheet, by an amount equal to its share of the net income transferred to reserves by the associate.

However, from a solvency standpoint, this method does not provide any clue to the group’s risk exposure and liabilities vis-à-vis its associate. The implication is that the group’s risk exposure is restricted to the value of its shareholding.

To illustrate the equity method of accounting, let us consider the following example based on the assumption that the parent company owns 20% of its associate:

The original balance sheets are as follows:

Parent company’s balance sheet

Associate’s balance sheet

Investment in the

associate

5

Shareholders’

equity

60

Assets

45

Shareholders’

equity

35

Other assets

57

Liabilities

2

Liabilities

10

In this scenario, the consolidated balance sheet would be as follows:

| Consolidated balance sheet | ||||

| Investment in the associate (5 − 5 + 20% × 35) | 7 | Shareholders’ equity (60 + 7 − 5) | 62 | |

| Other assets | 57 | Liabilities | 2 | |

The original income statements are as follows:

| Parent company’s income statement | Associate’s income statement | ||||||

| Costs | 80 | Net sales | 100 | Costs | 30 | Net sales | 35 |

| Net income | 20 | Net income | 5 | ||||

In this scenario, the consolidated income statement would be as follows:

| Consolidated income statement | |||

| Costs | 80 | Net sales | 100 |

| Net income (20 + 5 × 20%) | 21 | Minority interest (5 × 20%) | 1 |

Section 6.2 Consolidation-related issues

1. Scope of consolidation

The scope of consolidation, i.e. the companies to be consolidated, is determined using the rules we presented in Section 6.1. To determine the scope of consolidation, one needs to establish the level of control exercised by the parent company over each of the companies in which it owns shares.

(a) Level of control and ownership level

The level of control6 measures the strength of direct or indirect dependence that exists between the parent company and its subsidiaries, joint ventures or associates. Although control is assessed in a broader way in IFRS (see page 71), the percentage of voting rights that the parent company controls (what we call here “level of control”) will be a key indication to determine whether the subsidiary is controlled or significantly influenced.

To calculate the level of control, we must look at the percentage of voting rights held by all group companies in the subsidiary provided that the group companies are controlled directly or indirectly by the parent company.

Control is assumed when the percentage of voting rights held is 50% or higher or when a situation of de facto control exists at each link in the chain.

It is important not to confuse the level of control with the level of ownership. Generally speaking, these two concepts are different. The ownership level7 is used to calculate the parent company’s claims on its subsidiaries, joint ventures or associates. It reflects the proportion of their capital held directly or indirectly by the parent company. It is a financial concept, unlike the level of control, which is a power-related concept.

The ownership level is the sum of the product of the direct and indirect percentage stakes held by the parent company in a given company. The ownership level differs from the level of control, which considers only the controlled subsidiaries.

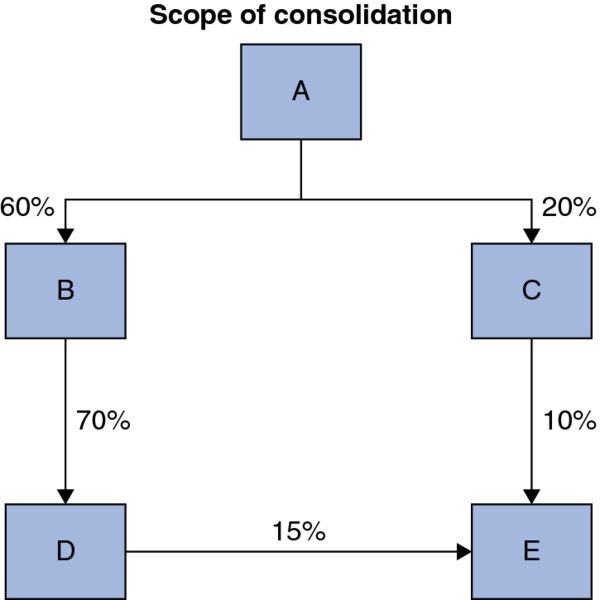

Consider the following example:

A controls 60% of B, B controls 70% of D, so A controls 70% of D. D and B are therefore considered as controlled and thus fully consolidated by A. But A does not own 70%, but 42% of D (i.e. 60% × 70%). The ownership level of A over D is then 42%: only 42% of D’s net income is attributable to A.

Since C owns just 10% of E, C will not consolidate E. Neither will D as it only owns 15% of E. But since A controls 20% of C, A will account for C under the equity method and will show 20% of C’s net income in its income statement.

The ownership level of A over E is 20% × 10% + 60% × 70% × 15% = 8.3%. The percentage of control of A over E is 15%.

How the ownership level is used varies from one consolidation method to another:

- with full consolidation, the ownership level is used only to allocate the subsidiary’s reserves and net income between the parent company and minority interests in the subsidiary;

- with the equity method of accounting, the ownership level is used to determine the portion of the subsidiary’s shareholders’ equity and net income attributable to the parent company.

(b) Changes in the scope of consolidation

It is important to analyse the scope of consolidation, especially with regard to what has changed and what is excluded. A decision not to consolidate a company means:

- neither its losses nor its shareholders’ equity will appear on the balance sheet8 of the group;

- its liabilities will not appear on the balance sheet of the group.

Certain techniques can be used to remove subsidiaries still controlled by the parent company from the scope of consolidation. These techniques have been developed to make certain consolidated accounts look more attractive. These techniques frequently involve a special-purpose vehicle (SPV). The SPV is a separate legal entity created specially to handle a venture on behalf of a company. In many cases, from a legal standpoint the SPV belongs to banks or to investors rather than to the company. That said, the company must consolidate the SPV if it controls it, as explained in the first paragraph of Section 6.1. These rules make it very difficult to use this type of scheme under IFRS or US GAAP.

Changes in the scope of consolidation require the preparation of pro forma financial statements. Pro forma statements enable analysts to compare the company’s performances on a consistent basis. In these pro forma statements, the company may either:

- restate past accounts to make them comparable with the current scope of consolidation; or

- remove from the current scope of consolidation any item that was not present in the previous period to maintain its previous configuration. This latter option is, however, less interesting for financial analysts.

2. Goodwill

It is very unusual for one company to acquire another for exactly its book value.

Generally speaking, there is a difference between the acquisition price, which may be paid in cash or in shares, and the portion of the target company’s shareholders’ equity attributable to the parent company. In most cases, this difference is positive as the price paid exceeds the target’s book value.

(a) What does this difference represent?

In other words, why should a company agree to pay out more for another company than its book value? There are several possible explanations:

- the assets recorded on the acquired company’s balance sheet are worth more than their carrying cost. This situation may result from the prudence principle, which means that unrealised capital losses have to be taken into account, but not unrealised capital gains;

- it is perfectly conceivable that assets such as patents, licences and market shares that the company has accumulated over the years without wishing to, or even being able to, account for them, may not appear on the balance sheet. This situation is especially true if the company is highly profitable;

- the merger between the two companies may create synergies, either in the form of cost reductions and/or revenue enhancement. The buyer is likely to partly reflect them in the price offered to the seller;

- the buyer may be ready to pay a high price for a target just to prevent a new player from buying it, entering the market and putting the current level of the buyer’s profitability under pressure;

- finally, the buyer may quite simply have overpaid for the deal.

(b) How is goodwill accounted for?

When first consolidated, the identifiable assets of the new subsidiary, joint venture or associate are valued at their fair value and are recorded on the group’s balance sheet in these amounts. Intangible assets in particular are valued even if they weren’t recognised on the acquired company’s balance sheet: brands concerned, patents, software, emissions permits or landing rights, customer lists, etc. Accordingly, the equity capital of the newly consolidated company will be revalued.

The difference between the price paid by the parent company for its shares in the acquired company and the parent company’s share in the revalued equity of the acquired company is called goodwill. It appears on the asset side of the new group’s balance sheet as intangible assets.

Under IFRS and US GAAP, goodwill is assessed each year to verify whether its value is at least equal to its net book value as shown on the group’s balance sheet. This assessment is called an impairment test. If the market value of goodwill is below its book value, then goodwill is written down to its fair market value and a corresponding impairment loss is recorded in the income statement.9 This impairment loss cannot be reversed in the future.

To illustrate the purchase method, let’s analyse now how Holcim accounted for the acquisition of Lafarge in 2015.

Prior to the acquisition, Holcim’s balance sheet (in millions of CHF) can be summarised as follows:

Intangible assets

6 238

Shareholders’ equity

19 279

Other fixed assets

20 465

Provisions

1 016

Working capital

1 046

Net debt

7 454

While Lafarge’s balance sheet (in millions of EUR) was as follows:

| Intangible assets | 11 412 | Shareholders’ equity | 17 563 |

| Other fixed assets | 15 318 | Provisions | 674 |

| Working capital | 111 | Net debt | 8 604 |

Holcim acquired 100% of Lafarge for CHF19 483m paid for in shares (CHF18 590m) and cash (CHF893m). Therefore, Holcim paid CHF1920m10 more than Lafarge equity. This amount is not equal to goodwill, as Holcim proceeded to a revaluation of assets and liabilities of Lafarge as follows:

|

−CHF10 382m +CHF7315m +CHF909m +CHF424m +CHF1971m |

Total adjustments amount to −CHF4553m (−10 382 + 7315 + 909 – 424 − 1971). Consequently, the amount of goodwill created was CHF1920m – (–CHF4553m) = CHF6473m. The simplified balance sheet of the combined entity was therefore as follows:

| Intangible assets | 6238 + 11 412 − 10 382 = 7268 | Shareholders’ equity | 19 279 + 18 590 = 37 869 |

| Goodwill | 6473 | Net debt | 7454 + 8604 + 1971 + 893 = 18 922 |

| Other fixed assets | 20 465 + 15 318 + 7315 = 43 098 | Provisions | 1016 + 674 + 424 = 2114 |

| Working capital | 1046 + 111 + 909 = 2066 |

Finally, transactions may give rise to negative goodwill under certain circumstances. Under IFRS, negative goodwill is immediately recognised as a profit in the income statement of the new groups.

(c) How should financial analysts treat goodwill?

From a financial standpoint, it is sensible to regard goodwill as an asset like any other, which may suffer sudden falls in value that need to be recognised by means of an impairment charge. We advise our readers to treat impairment charges as non-recurring items and to exclude them for the computation of returns (see Chapter 13) or earnings per share (see Chapter 22).

Can it be argued that goodwill impairment losses do not reflect any decrease in the company’s wealth because there is no outflow of cash? We do not think so.

Granted, goodwill impairment losses are a non-cash item, but it would be wrong to say that only decisions giving rise to cash flows affect a company’s value. For instance, setting a maximum limit on voting rights or attributing 10 voting rights to certain categories of shares does not have any cash impact, but definitely reduces the value of shareholders’ equity.

Recognising the impairment of goodwill related to a past acquisition is tantamount to admitting that the price paid was too high. But what if the acquisition was paid for in shares? This makes no difference whatsoever, irrespective of whether the buyer’s shares were overvalued at the same time.

Had the company carried out a share issue rather than overpaying for an acquisition, it would have been able to capitalise on its lofty share price to the great benefit of existing shareholders. The cash raised through the share issue would have been used to make acquisitions at much more reasonable prices once the wave of euphoria had subsided.

It is essential to remember that shareholders in a company which pays for a deal in shares suffer dilution in their interest. They accept this dilution because they take the view that the size of the cake will grow at a faster rate (e.g. by 30%) than the number of guests invited to the party (e.g. by over 25%). Should it transpire that the cake grows at merely 10% rather than the expected 30% because the purchased assets prove to be worth less than anticipated, then the number of guests at the party will unfortunately stay the same. Accordingly, the size of each guest’s slice of the cake falls by 12% (110/125 − 1), so shareholders’ wealth has certainly diminished.

(d) How should financial analysts treat “adjusted income”?

Some groups (particularly in the pharmaceutical sector) like Pfizer or Sanofi, following an acquisition, publish an “adjusted income” to neutralise the P&L impact of the revaluation of assets and liabilities of its newly acquired subsidiary. Naturally, a P&L account is drawn up under normal standards, but it carries an audited table showing the impact of the switch to adjusted income on operating income and net income.

As a matter of fact, by virtue of the revaluation of the target’s inventories to their market value, the normal process of selling the inventories generates no profit. So how relevant will the P&L be in the first year after the merger? This issue becomes critical only when the production cycle is very long and therefore the revaluation of inventories (and potentially research and development capitalised) is material.

We believe that for those specific cases, groups are right to show this adjusted P&L.

Section 6.3 Technical aspects of consolidation

1. Harmonising accounting data

Since consolidation consists of aggregating accounts give or take some adjustments, it is important to ensure that the accounting data used are consistent, i.e. based on the same principles.

Usually, the valuation methods used in individual company accounts are determined by accounting or tax issues specific to each subsidiary, especially when some of them are located outside the group’s home country. This is particularly true for provisions, depreciation and amortisation, fixed assets, inventories and work in progress, deferred charges and shareholders’ equity.

These differences need to be eliminated upon consolidation. This process is facilitated by the fact that most of the time consolidated accounts are not prepared to calculate taxable income, so groups may disregard the prevailing tax regulations.

Prior to consolidation, the consolidating company needs to restate the accounts of the to-be-consolidated companies. The consolidating company applies the same valuation principles and makes adjustments for the impact of the valuation differences that are justified on tax grounds, e.g. tax-regulated provisions, accelerated depreciation for tax purposes and so on.

2. Eliminating intra-group transactions

Consolidation entails more than the mere aggregation of accounts. Before the consolidation process as such can begin, intra-group transactions and their impact on net income have to be eliminated from the accounts of both the parent company and its consolidated companies.

Assume, for instance, that the parent company has sold to subsidiaries products at cost plus a margin. An entirely fictitious gain would show up in the group’s accounts if the relevant products were merely held in stock by the subsidiaries rather than being sold on to third parties. Naturally, this fictitious gain, which would be a distortion of reality, needs to be eliminated.

Intra-group transactions to be eliminated upon consolidation can be broken down into two categories:

- Those that are very significant because they affect consolidated net income. It is therefore vital for such transactions to be reversed. The goal is to avoid showing two profits or showing the same profit twice in two different years. The reversal of these transactions upon consolidation leads primarily to the elimination of:

- intra-group profits included in inventories;

- capital gains arising on the transfer or contribution of investments;

- dividends received from consolidated companies;

- impairment losses on intra-group loans or investments; and

- tax on intra-group profits.

- Those that are not fundamental because they have no impact on consolidated net income or those affecting the assets or liabilities of the consolidated entities. These transactions are eliminated through netting, so as to show the real level of the group’s debt. They include:

- parent-to-subsidiary loans (advances to the subsidiary) and vice versa;

- interest paid by the parent company to the consolidated companies (financial income of the latter) and vice versa.

3. Translating the accounts of foreign subsidiaries

(a) The problem

The translation of the accounts of foreign companies is a tricky issue because of exchange rate fluctuations and the difference between inflation rates, which may distort the picture provided by company accounts.

For instance, a parent company located in the eurozone may own a subsidiary in a country with a soft currency.12

Using year-end exchange rates to convert the assets of its subsidiary into the parent company’s currency understates their value. From an economic standpoint, all the assets do not suffer depreciation proportional to that of the subsidiary’s home currency.

On the one hand, fixed assets are protected to some extent. Inflation means that it would cost more in the subsidiary’s local currency to replace them after the devaluation in the currency than before. All in all, the inflation and devaluation phenomena may actually offset each other, so the value of the subsidiary’s fixed assets in the parent company’s currency is roughly stable. On the other hand, inventories, receivables and liabilities (irrespective of their maturity) denominated in the devalued currency all depreciate in tandem with the currency.

If the subsidiary is located in a country with a hard currency (i.e. a stronger one than that of the parent company), then the situation is similar but the implications are reversed.

To present an accurate image of developments in the foreign subsidiary’s situation, it is necessary to take into account:

- the impact on the consolidated accounts of the translation of the subsidiary’s currency into the parent company’s currency;

- the adjustment that would stem from translation of the foreign subsidiary’s fixed assets into the local currency.

(b) Methods

Several methods may be used at the same time to translate different items in the balance sheet and income statement of foreign subsidiaries, giving rise to currency translation differences.

The most frequently used method is called the closing rate method: all assets and liabilities are translated at the closing rate, which is the rate of exchange at the balance sheet date.13 Revenues and charges on the income statement are translated at the average rate over the fiscal year.14 Currency translation differences are recorded under shareholders’ equity, with a distinction being made between the group’s share and that attributable to minority investors. This translation method is used under IFRS and it is relatively comparable to the US standard.

The temporal method consists of translating:

- monetary items (i.e. cash and sums receivable or payable denominated in the foreign company’s currency and determined in advance) at the closing rate;

- non-monetary items (fixed assets and the corresponding depreciation and amortisation,15 inventories, prepayments, shareholders’ equity, investments, etc.) at the exchange rate at the date to which the historical cost or valuation pertains;

- revenues and charges on the income statement theoretically at the exchange rate prevailing on the transaction date. In practice, however, they are usually translated at an average exchange rate for the period.

Under the temporal method, the difference between the net income on the balance sheet and that on the income statement is recorded on the income statement under foreign exchange gains and losses.

(c) Translating the accounts of subsidiaries located in hyperinflationary countries

A hyperinflationary country is one where inflation is both chronic and out of control. In such circumstances, the previous methods are not suitable for translating the effects of inflation into the accounts.

Hence the use of a specific method based on restatements made by applying a general price index. Elements such as monetary items that are already stated at the measuring unit at the balance sheet date are not restated. Other elements are restated based on the change in the general price index between the date those items were acquired or incurred and the balance sheet consolidation. A gain or loss on the net monetary position is included in net income. IFRS prescribes this method, which is not allowed in the US where the temporal method is applied.

Summary

Questions

Exercises

Answers

Notes

Bibliography