Chapter 49

Cash management

A balancing act …

Cash management is the traditional role of the treasury function. It handles cash inflows and outflows, as well as intra-group fund transfers. With the development of information systems, this function is usually automated. As a result, the treasurer merely designs or chooses a model, and then supervises the day-to-day operations. Nonetheless, we need to take a closer look at the basic mechanics of the treasury function to understand the relevance and impact of the different options.

Sections 49.1 and 49.2 explain the basic concepts of cash management, as well as its main tools. These factors are common to both small companies and multinational groups. Conversely, the cash pooling units described in Section 49.3 remain the sole preserve of groups.

Section 49.1 The basics

1. Value dating

From the treasurer’s standpoint, the balance of cash flows is not the same as that recorded in the company’s accounts or that shown on a bank statement. An example can illustrate these differences.

Example: A, a company headquartered in Amsterdam, issues a cheque for €1000 on 15 April to its supplier R in Rotterdam. Three different people will record the same amount, but not necessarily on the same date:

- A’s accountant, for whom the issue of the cheque theoretically makes the sum of €1000 unavailable as soon as the cheque has been issued;

- A’s banker, who records the €1000 cheque when it is presented for payment by R’s bank. He then debits the amount from the company’s account based on this date;

- A’s treasurer, for whom the €1000 remains available until the cheque has been debited from the relevant bank account. The date of debit depends on when the cheque is cashed in by the supplier and how long the payment process takes.

There may be a difference of a few days between these three dates, which determines movements in the three separate balances.

Cash management based on value dates, in countries where this system is used,1 is built on an analysis from the treasurer’s standpoint. The company is interested only in the periods during which funds are actually available. Positive balances can then be invested or used, while negative balances generate real interest expense.

The date from which a bank makes incoming funds available to its customers does not always correspond exactly to the payment date. As a result, a value date can be defined as follows:

- for an interest-bearing account, it represents the date from which an amount credited to the account bears interest following a collection of funds; and the date from which an amount debited from the account stops bearing interest following a disbursement of funds;

- for a demand deposit account,2 it represents the date from which an amount credited to the account may be withdrawn without the account holder having to pay overdraft interest charges (in the event that the withdrawal would make the account show a debit balance) following a collection; and the date from which an amount debited from the account becomes unavailable following a disbursement.

Under this system, it is therefore obvious that:

- a credit amount is given a value date after the credit date for accounting purposes;

- a debit amount is given a value date prior to the debit date for accounting purposes.

Let us consider, for example, the deposit of the €1000 cheque received by R when the sum is paid into an account. We will assume that the cash in process is assigned a value date one banking day later, and that on the same day R makes a withdrawal of €300 in cash, with a similar value date.

Although the initial account balance is zero, R’s account is in debit on a value date basis and in credit from an accounting standpoint.

Although the account balance always remains in credit from an accounting standpoint, the balance from a value date standpoint shows a debit of €300 until D + 1. The company will therefore incur interest expense, even though its financial statements show a credit balance.

In the European Economic Area, only cheques still have a value date of a maximum of one working day (because of the time required to handle them physically) and other transactions are credited or debited on the day on which they are executed. The transaction may, however, be executed the following day if it is transmitted too late in the afternoon (after the cut-off time set by the bank).

2. Account balancing

Company bank current accounts are intended simply to cover day-to-day cash management. They offer borrowing and investment conditions that are far from satisfactory:

- the cost of an overdraft is much higher than that of any other type of borrowing;

- the interest rate paid on credit balances is low or zero and is well below the level that can be obtained on the financial markets.

It is therefore easy to understand why it makes little sense for the company to run a permanent credit or debit balance on a bank account. A company generally has several accounts with various different banks. An international group may have several hundred accounts in numerous different currencies, although the current trend is towards a reduction in the number of accounts operated by businesses.

One of the treasurer’s primary tasks is to avoid financial expense (or reduced financial income) deriving from the fact that some accounts are in credit while others show a debit balance. The practice of account balancing is based on the following two principles:

- avoiding the simultaneous existence of debit and credit balances by transferring funds from accounts in credit to those in debit;

- channelling cash outflows and cash inflows so as to arrive at a balanced overall cash position.

Banks offer account balancing services, whereby they automatically make the requisite transfers to optimise the balance of company accounts.

3. Bank charges

The return on equity3 generated by a bank from a customer needs to be analysed by considering all the services, loans and other products the bank offers, including some:

- not charged for and thus representing unprofitable activities for the bank (e.g. cheques deposited by retail customers);

- charged for over and above their actual cost, notably using charging systems that do not reflect the nature of the transaction processed.

Banks now tend to invoice companies the actual price of the financial flow management services provided, through ad hoc charges. This activity is no longer seen as one of the ways of compensating for an undervalued price of loans as part of an overall relationship (the business side in Section 39.1). Banks currently see managing the financial flows of companies as a strategic activity, enabling them to better understand their clients’ risks on the basis of their financial flows and to improve their own liquidity (Basel III ratios). It should be noted that fees charged by banks are not always transparent, and companies are lobbying for the standardisation of fees through electronic reporting, similar to the Bank Service Billing system in the USA.

Section 49.2 Cash management

1. Cash budgeting

The cash budget shows not only the cash flows that have already taken place, but also all the receipts and disbursements that the company plans to make. These cash inflows and outflows may be related to the company’s investment, operating or financing cycles.

The cash budget, showing the amount and duration of expected cash surpluses and deficits, serves two purposes:

- to ensure that the credit lines in place are sufficient to cover any funding requirements;

- to define the likely uses of loans by major categories (e.g. the need to discount based on the company’s portfolio of trade bills and drafts).

Planning cash requirements and resources is a way of adapting borrowing and investment facilities to actual needs and, first and foremost, of managing a company’s interest expense. It is easy to see that a better rate loan can be negotiated if the need is forecast several months in advance. Likewise, a treasury investment will be more profitable over a predetermined period, during which the company can commit not to use the funds.

The cash budget is a forward-looking management chart showing supply and demand for liquidity within the company. It allows the treasurer to manage interest expense as efficiently as possible by harnessing competition not only among different banks, but also with investors on the financial markets.

2. Forecasting horizons

Different budgets cover different forecasting horizons for the company. Budgets can be used to distinguish between the degree of accuracy users are entitled to expect from the treasurer’s projections.

Companies forecast cash flows by major categories over long-term periods and refine their projections as cash flows draw closer in time. Thanks to the various services offered by banks, budgets do not need to be 100% accurate, but can focus on achieving the relevant degree of precision for the period they cover.

An annual cash budget is generally drawn up at the start of the year based on the expected profit and loss account, which has to be translated into cash flows. The top priority at this point is for cash flow figures to be consistent and material in relation to the company’s business activities. At this stage, cash flows are classified by category rather than by type of payment.

These projections are then refined over periods ranging from one to six months to yield rolling cash budgets, usually for monthly periods. These documents are used to update the annual budgets based on the real level of cash inflows and outflows, rather than using expected profit and loss accounts.

Day-to-day forecasting represents the final stage in the process. This is the basic task of all treasurers and the basis on which their effectiveness is assessed. Because of the precision required, day-to-day forecasting gives rise to complex problems:

- it covers all the movements affecting the company’s cash position;

- each bank account needs to be analysed;

- it is carried out on a value date basis;

- it exploits the differences between the payment methods used;

- as far as possible, it distinguishes between cash flows on a category-by-category basis.

The following table summarises these various aspects:

Day-to-day forecasting has been made much easier by IT systems. Thanks to the ERP4 and other IT systems used by most companies, the information received by the various parts of the business is processed directly and can be used to forecast future disbursements instantaneously. As a result, cash budgeting is linked to the availability of information and thus of the characteristics of the payment methods used.

3. The impact of payment methods

The various payment methods available raise complex problems and may give rise to uncertainties that are inherent in day-to-day cash forecasting. There are two main types of uncertainty:

- Is the forecast timing of receipts correct? A cheque may have been collected by a sales agent without having immediately been paid into the relevant account. It may not be possible to forecast exactly when a client will pay down its debt by bank transfer.

- When will expenditure give rise to actual cash disbursements? It is impossible to say exactly when the creditor will collect the payment that has been handed over (e.g. cheque, bill of exchange or promissory note).

From a cash budgeting standpoint, payment methods are more attractive where one of the two participants in the transaction possesses the initiative both in terms of setting up the payment and triggering the transfer of funds. Where a company has this initiative, it has much greater certainty regarding the value dates for the transfer.

The following table shows an analysis of the various payment methods used by companies from this standpoint. It does not take into account the risk of non-payment by a debtor (e.g. not enough funds in the account, insufficient account details, refusal to pay). This risk is self-evident and applies to all payment methods.

| Initiative for setting up transfer | Initiative for completing fund transfer | Utility for cash budgeting | |

| Cheque | Debtor | Creditor | None |

| Paper bill of exchange5 | Creditor | Creditor | Helpful to both parties insofar as the deadlines are met by the creditors |

| Electronic bill of exchange6 | Creditor | Creditor | |

| Paper promissory note7 | Debtor | Creditor | |

| Electronic promissory note8 | Debtor | Creditor | |

| Transfer9 | Debtor | Debtor | Debtor |

| Debit10 | Creditor | Creditor | Creditor |

From this standpoint, establishing the actual date on which cheques will be paid represents the major problem facing treasurers. Postal delays and the time taken by the creditor to record the cheque in its accounts and to hand it over to its bank affect the debit date. Consequently, treasurers endeavour to:

- process cheques for small amounts globally, to arrive at a statistical rule for collection dates, if possible by periods (10th, 20th, end-of-month);

- monitor large cheques individually to get to know the collection habits of the main creditors, e.g. public authorities (social security, tax, customs, etc.), large suppliers and contractors.

Although their due date is generally known, domiciled bills11 and notes can also cause problems. If the creditor is slow to collect the relevant amounts, the debtor, which sets aside sufficient funds in its account to cover payment on the relevant date, is obliged to freeze the funds in an account that does not pay any interest. Once again, it is in the interests of the debtor company to work out a statistical rule for the collection of domiciled bills and notes and to get to know the collection habits of its main suppliers.

Aside from the problems caused by forecasting uncertainties, payment methods do not all have the same flexibility in terms of domiciliation, i.e. the choice of account to credit or debit. The customer cheques received by a company may be paid into an account chosen by the treasurer. The same does not apply to standing orders and transfers, where the account details must usually be agreed in advance and for a certain period of time. This lack of flexibility makes it harder to balance accounts. Lastly, the various payment methods have different value dates. The treasurer needs to take the different value dates into account very carefully in order to manage his account balances on a value date basis.

Each country has its own history and payment habits in Europe; these are far from being unified.

Source: European Central Bank, 2016

Harmonisation of payment methods in the eurozone (Single Euro Payment Area, or SEPA) has allowed companies or individuals to transfer money and debits as easily and as quickly and at the same cost as if the transfer were between two towns in the same country.

New payment methods that take advantage of the SEPA standard have been developed, such as SEPAmail, the main service of which is an email transfer for paying invoices at radically reduced processing costs, much faster processing periods and reduced risks of fraud. This is what Blockchain will be able to do on a very large scale, once it is developed beyond the hype and the buzz surrounding it today.

4. Optimising cash management

Our survey of account balancing naturally leads us to the concept of zero cash, the nirvana of corporate treasurers, which keeps interest expense down to a minimum (even though in the current climate of very low, even negative, short-term interest rates, this is becoming a worry of the past).

Even so, this aim can never be completely achieved. A treasurer always has to deal with some unpredictable movements, be they disbursements or collections. The greater the number or volume of unpredictable movements, the more imprecise cash budgeting will be and the harder it is to optimise. That said, several techniques may be used to improve cash management significantly.

(a) Behavioural analysis

The same type of analysis as performed for payment methods can also yield direct benefits for cash management. The company establishes collection times based on the habits of its suppliers. A statistical average for collection times is then calculated. Any deviations from the normal pattern are usually offset where an account sees a large number of transactions. This enables the company to manage the cash balance on each account to “cover” payments forecast with a certain delay of up to four or five days for value date purposes.

In any case, payments will always be covered by the overdraft facilities agreed with the bank, the only risk for the company being that it will run an overdraft for some limited period and thus pay higher interest expense.

(b) Intercompany agreements

Since efficient treasury management can unlock tangible savings, it is normal for companies that have commercial relationships to get together to maximise these gains. Various types of contract have been developed to facilitate and increase the reliability of payments between companies. Some companies have attempted to demonstrate to their customers the mutual benefits of harmonisation of their cash management procedures and negotiated special agreements. In a bid to minimise interest expense attributable to the use of short-term borrowings, others offer discounts to their customers for swift payment. Nonetheless, this approach has drawbacks because, for obvious commercial reasons, it is hard to apply the stipulated penalties when contracts are not respected.

(c) Lockbox systems

Under the lockbox system, the creditor asks its debtors to send their payments directly to a PO box that is emptied regularly by its bank. The funds are immediately paid into the banking system, without first being processed by the creditor’s accounting department.

When the creditor’s and debtor’s banks are located in the same place, cheques can easily be cleared on the spot. Such clearing represents another substantial time saving.

(d) Checking bank terms

The complexity of bank charges and the various different items on which they are based makes them hard to check. This task is thus an integral part of a treasurer’s job.

Companies implement systematic procedures to verify all the aspects of bank charges. The conditions used to calculate interest payments and transaction charges may be verified by reconciling the documents issued by the bank (particularly interest-rate scales and overdraft interest charges) with internal cash monitoring systems. Flat-rate charges may be checked on a test basis.

Section 49.3 Cash management within a group

Managing the cash position of a group adds an additional layer of data-processing and decision-making based on principles that are exactly the same as those explained in Sections 49.1 and 49.2 for individual companies (i.e. group subsidiaries or SMEs12).

1. Centralised cash management

The methods explained in the previous sections show the scale of the task facing a treasury department. It therefore seems natural to centralise cash management on a group-wide basis, a technique known as cash pooling, since it allows a group to take responsibility for all the liquidity requirements of its subsidiaries.

The cash positions of the subsidiaries (lenders or borrowers) can thus be pooled in the same way as the various accounts of a single company, thereby creating a genuine internal money market. The group will thus save on all the additional costs deriving from the inefficiencies of the financial markets (bank charges, brokerage fees, differences between lending and borrowing rates, etc.). In particular, cash pooling enables a group to hold on to the borrowing/lending margin that banks are normally able to charge.

This is not the only benefit of pooling. It gives a relatively big group comprising a large number of small companies the option of tapping financial markets. Information-related costs and brokerage fees on an organised market may prevent a large number of subsidiaries from receiving the same financing or investment conditions as the group as a whole. With the introduction of cash pooling, the corporate treasurer can address the financing needs of the entire group by going to market. The treasurer then organises an internal refinancing of each subsidiary on the same financing terms that the group receives.

Cash pooling has numerous advantages. The manager’s workload is not proportional to the number of transactions or the size of the funds under management. Consequently, there is no need to double the size of a department handling the cash needs of twice the number of companies. The skills of existing teams will nevertheless need to be enhanced. Likewise, investment in systems (hardware, software, communication systems, etc.) can be reduced when they are pooled within a single central department. Information-gathering costs can yield the same type of saving. Consequently, cash pooling offers scope for genuine “industrial” economies of scale.

Although the creation of a cash pooling unit may be justified for very good reasons, it may also lead to an unwise financial strategy and possibly even management errors. Notably, cash pooling will give rise to an internal debt market totally disconnected from the assets being financed. Certain corporate financiers may still be heard to claim that they have secured better financing or investment terms by leveraging the group’s size or the size of the funds under management.

Let’s not confuse two situations which are different. On the one hand, we have integration within a much larger set of smaller companies in the same sector, which immediately enjoy better financial terms that the group has access to thanks to its size and strong negotiating position. On the other hand, the integration of higher-risk entities, which, if they are able to get better financial terms, owe this either to the shortsightedness of lenders and rating agencies (which won’t last) or to the detriment of the cost of financing of the whole (which will rise). We should not forget that in a market economy, only the level of risk of each investment determines its cost of financing. Any other line of reasoning is not tenable over the long term.

A prerequisite for cash pooling is the existence of an efficient system transmitting information between the parent company and its subsidiaries (or between the head office and decentralised units). The system requires the subsidiaries to send their forecasts to the head office in real time. The rapidity of fund movements – i.e. the unit’s efficiency – depends on the quality of these forecasts, as well as on that of the corporate information system.

Lastly, a high degree of centralisation can reduce the risks of fraud but also reduces the subsidiaries’ ability to take initiatives. The limited responsibilities granted to local cash managers may encourage them not to optimise their own management when it comes to either conducting behavioural analysis of payments or controlling internal parameters. Local borrowing opportunities at competitive rates may therefore go begging. To avoid demotivating the subsidiaries’ treasurers, they may be given greater responsibility for local cash management.

2. The different types and degrees of centralisation

Looking beyond its unifying nature in theory, there are many different ways of pooling a group’s cash resources in practice, ranging from the outright elimination of the subsidiaries’ cash management departments to highly decentralised management. There are two major types of organisation, which reflect two opposite approaches:

- Most common is the centralisation of balances and liquidity, which involves the group-wide pooling of cash from the subsidiaries’ bank accounts. The group balances the accounts of its subsidiaries just as the subsidiaries balance their bank accounts. There are a number of different variations on this system.

- Significantly rarer is the centralisation of cash flows, under which the group’s cash management department not only receives all incoming payments, but may also even make all the disbursements. The department deals with issues such as due dates for customer payments and customer payment risks, reducing the role of any subsidiary to providing information and forecasting. This type of organisation may be described as hypercentralised.

The centralisation of cash balances can be dictated from above or carried out upon request of the subsidiary. In the latter case, each subsidiary decides to use the group’s cash or external resources in line with the rates charged, thereby creating competition between the banks, the market and internal funds. This flexibility can help alleviate any demotivation caused by the centralisation of cash management.

In addition, coherent cash management requires the definition of uniform banking terms and conditions within a group.

Notional pooling provides a relatively flexible way of exploiting the benefits of cash pooling. With notional pooling, subsidiaries’ account balances are never actually balanced, but the group’s bank recalculates credit or debit interest based on the fictitious balance of the overall entity. This method yields exactly the same result as if the accounts had been perfectly balanced, but the fund transfers are never carried out in practice. As a result, this method leaves subsidiaries some room for manoeuvre and does not impact on their independence.

A high-risk subsidiary thus receives financing on exactly the same terms as the group as a whole, while the group can benefit from limited liability from a legal standpoint by declaring its subsidiary bankrupt. Notional pooling prevents a bank from adjusting its charges, thus introducing additional restrictions and setting reciprocal guarantees between each of the companies participating in the pooling arrangements. This often takes the form of a guarantee given by the parent company (parent company guarantee, PCG).

Consequently, cash balances are more commonly pooled by means of the daily balancing of the subsidiaries’ positions. The zero balance account (ZBA) concept requires subsidiaries to balance their position (i.e. the balance of their bank accounts) each day by using the concentration accounts managed at group or subgroup level. The banks offer automated balancing systems and can perform all these tasks on behalf of companies. The use of ZBA requires a set of legal agreements between the parent company and each subsidiary (cash management agreements), which must be negotiated at arm’s length so as not to raise any legal or tax issues.

In summary, the degree of centralisation of cash management and the method used by a group do not depend on financial criteria only. The three key factors are as follows:

- the group’s managerial culture, e.g. notional pooling, is more suited to highly decentralised organisations than daily position balancing;

- regulations and tax systems in the relevant countries;

- the cost of banking services. While position balancing is carried out by the group, notional pooling is the task of the bank.

3. International cash management

The problems arising with cash pooling are particularly acute in an international environment. That said, international cash management techniques are exactly the same as those used at national level, i.e. pooling on demand, notional pooling, account balancing.

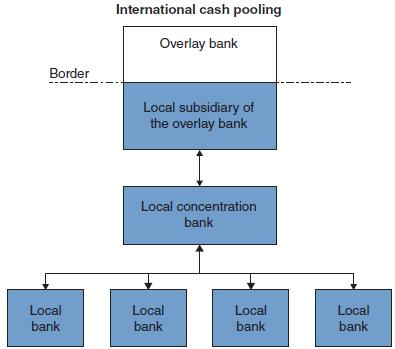

Regulatory differences make the direct pooling of account balances of foreign subsidiaries a tricky task. Indeed, many groups find that they cannot do without the services of local banks, which are able to collect payments throughout a given zone. Consequently, multinational groups tend to apply a two-tier pooling system. A local concentration bank performs the initial pooling process within each country, and an international banking group, called an overlay bank, then handles the international pooling process.

The international bank sends the funds across the border,13 as shown in the chart above, which helps to dispense with a large number of regulatory problems.

At the local level, centralisation can be tailored to the specific regulatory requirements in each country, while at a higher level the international bank can carry out both notional pooling and daily account balancing. Lastly, it can manage the subsidiaries’ interest and exchange rate risks (see Chapter 50) by offering exchange-rate and interest-rate guarantees. The structure set up can be used to manage all the group’s financial issues rather than just the cash management aspects.

Within the eurozone, the interconnection of payment systems under the aegis of the European Central Bank has made it possible to carry out fund transfers in real time, more cheaply and without having to face the issue of value dating. In the eurozone, cash pooling may thus be carried out with the assistance of a single concentration bank in each country with cross-border transfers not presenting any problems.

More and more groups have created a payment factory which pays off all the group’s suppliers on behalf of all the subsidiaries, which reduces the number of transfers when subsidiaries have common suppliers.

4. Cash management of a group experiencing financial difficulties

We ought to mention that all of the techniques and products discussed in this chapter work best for a group in good financial health and which accordingly has easy access to the debt market.

The treasurer of a group whose finances are stretched also has to manage its cash with as much, if not more, care and attention, although the goals of such a treasurer will obviously be a lot different from those of the treasurer of a more financially sound group. Instead of seeking to optimise financial expenses, the treasurer will want to secure the group’s financing.

Accordingly, he will maximise the amount of loans granted, even if this means taking out more short-term debt than is actually needed to meet short-term requirements.

When the going gets tough, the group will be able to draw on all of its credit lines, as long as it is still meeting its financial covenants,14 and place the funds in short-term investments. So, if the situation gets worse, the group will not run the risk of having its credit lines cut off by the banks. The banks will be forced to work with the company in order to turn it around financially.

Looking after a company’s cash turns out to be more of an operational monitoring job than an optimisation one. In fact, and paradoxically, the treasurer succeeds in managing the company’s cash only thanks to its short-term investments.

This situation could raise the cost of debt for the company, but this additional cost is no more than a form of insurance against a liquidity risk!

Section 49.4 Investing cash balances

Financial novices may wonder why debt-burdened companies do not use their cash to reduce debt. There are two good reasons for this:

- Paying back debt in advance can be costly because of early repayment penalties, or unwise if the debt was contracted at a rate that is lower than the rates prevailing today.

- Keeping cash on hand enables the company to seize investment opportunities quickly and without constraints or to withstand changes in the economic environment. Some research papers15 have demonstrated that companies with strong growth or volatile cash flows tend to have more available cash than average. Conversely, companies that have access to financial markets or excellent credit ratings have less cash than average.

Obviously, all financing products used by companies have a mirror image as investment products, since the two operations are symmetrical. The corporate treasurer’s role in investing the company’s cash is nevertheless somewhat specific, because the purpose of the company is not to make profits by engaging in risky financial investments. This is why specific products have been created to meet this criterion.

Remember that all investment policies are based on anticipated developments in the bank balances of each account managed by the company or, if it is a group, on consolidated, multicurrency forecasts. The treasurer cannot decide to make an investment without first estimating its amount and the duration. Any mistake, and the treasurer is forced to choose between two alternatives:

- either resort to new loans to meet the financial shortage created if too much cash was invested, thus generating a loss (negative margin) on the difference between lending and borrowing rates (i.e. the interest rate spread); or

- retrieve the amounts invested and incur the attendant penalties, lost interest or (in certain cases such as bond investments) risk of a capital loss.

Since corporate treasurers rarely know exactly how much cash they will have available for a given period, their main concern when choosing an investment is its liquidity – that is, how fast it can be converted back into cash. For an investment to be cashed in immediately, it must have an active secondary market or a redemption clause that can be activated at any time.

Of course, if an investment can be terminated at any time, its rate of return can be uncertain since the exit price can be uncertain. A 91-day Treasury bill at a nominal rate of 4% can be sold at will, but its actual rate of return will depend on whether the bill was sold for more or less than its nominal value. However, if the rate of return is set in advance, it is virtually impossible to exit the investment before its maturity, since there is no secondary market or redemption clause, or if there is, only at a prohibitive cost.

Within the context of this liquidity-security, the treasurer should not forget that:

- accounting standards strictly define investments that can be classified as cash equivalents: they must be short term (in general less than three months), very liquid, easily convertible into a known amount of cash and subject to a negligible risk of any change in value. This classification has consequences for the definition of net debt in terms of banking covenants;

- the risk of a bank collapsing is not just a theoretical risk. A bank that offers substantially higher interest on deposits than its competitors may do so because it’s having trouble finding cash, which is not a good sign. Counterparty risk also means that companies should diversify the banks they place their cash with and not put all of their eggs into one basket;

- readily available products may fall under a different tax regime.

1. Investment products with no secondary market

Interest-bearing current accounts are offered by banks in order to be able to capture liquidity so as to improve their regulatory solvency ratios. Interest may be fixed or rise over time (extending the life of these deposits).

Time deposits are fixed-term deposits on an interest-bearing bank account that are governed by a letter signed by the account holder. The interest on deposits with maturity of at least one month is negotiated between the bank and the client. It can be at a fixed rate or indexed to the money market. No interest is paid if the client withdraws the funds before the agreed maturity date.

Cash certificates are time deposits that take the physical form of a bearer or registered certificate.

Repos (repurchase agreements) are agreements whereby institutional investors or companies can exchange cash for securities for a fixed period of time (a securities for cash agreement is called a “reverse repo”). At the end of the contract, which can take various legal forms, the securities are returned to their original owner. All title and rights to the securities are transferred to the buyer of the securities for the duration of the contract. The only risk is that the borrower of the cash (the repo seller) will default.

Repo sellers hold equity or bond portfolios, while repo buyers are looking for cash revenues. From the buyer’s point of view, a repo is basically an alternative solution when a time deposit is not feasible, for example for periods of less than one month. A repo allows the seller to obtain cash immediately by pledging securities with the assurance that it can buy them back.

Since the procedure is fairly unwieldy, it is only used for large amounts, well above €2m. This means that it competes with negotiable debt securities, such as commercial paper. However, the development of money market mutual funds investing in repos has lowered the €2m threshold and opened up the market to a larger number of companies.

2. Investment products with a secondary market

Treasury bills and notes are issued by governments at monthly or weekly auctions for periods ranging from two weeks to five years. They are the safest of all investments given the creditworthiness of the issuer (governments), but their other features make them less flexible and competitive. However, the substantial amount of outstanding negotiable Treasury bills and notes ensures sufficient liquidity, even for large volumes. These instruments can be a fairly good vehicle for short-term investments.

Certificates of deposit (CDs) are quite simply time deposits represented by a dematerialised negotiable debt security in the form of a bearer certificate or order issued by an authorised financial institution. Certificates of deposit are issued in minimum amounts for periods ranging from one day to one year with fixed maturity dates. In fact, they are a form of short-term investment. CDs are issued by banks, for which they are a frequent means of refinancing, on a continuous basis depending on demand. Before the financial crisis of 2008, their yield was very close to that of the money market, and their main advantage is that they can be traded on the secondary market, thus avoiding the heavy penalties of cashing in time deposits before their maturity date. The flip side is that they carry an interest-rate risk.

We described the main characteristics of commercial paper and medium-term negotiable notes in Chapter 21.

Money-market or cash mutual funds are funds that issue or buy back their shares at the request of investors at prices that must be published daily. The return on a money-market capitalisation mutual fund arises from the daily appreciation in net asset value (NAV). This return is similar to that of the money market. Depending on the mutual fund’s stated objective, the increase in NAV is more or less steady. A very regular progression can only be obtained at the cost of profitability.

In order to meet its objectives, each cash mutual fund invests in a selection of Treasury bills, certificates of deposit, commercial paper, repos and variable or fixed-rate bonds with a short residual maturity. Its investment policy is backed by quite sophisticated interest-rate risk management.

The subprime crisis was a healthy (but costly!) reminder for some treasurers that an increase in return cannot be obtained without an increase in risk. Some money-market funds, nicknamed “turbo” or “dynamic”, had invested part of their portfolio in subprime securities to boost their returns. During the summer of 2007 and thereafter, their performances suffered severely and the majority of them lost most of their customers.

Securitisation vehicles are special-purpose vehicles created to take over the claims sold by a credit institution or company engaging in a securitisation transaction (see Chapter 21). In exchange, these vehicles issue units that the institution sells to investors.

In theory, bond investments should yield higher returns than money-market or money-market-indexed investments. However, interest-rate fluctuations generate capital risks on bond portfolios that must be hedged, unless the treasurer has opted for short-maturity bonds or floating-rate bonds. Investing in bonds therefore calls for a certain degree of technical know-how and constant monitoring of the market. Only a limited number of treasurers have the resources to invest directly in bonds.

The high yields arising from investing surplus cash in the equity market over long periods become far more uncertain on shorter horizons, when the capital risk exposure is very high. Equity investments are theoretically only used very marginally and only for surplus cash over the long term. However, treasurers may be charged with monitoring portfolios of equity interests.

The current context of very low or even negative interest rates is forcing treasurers to think about the maximum level of acceptable risk. Some banks are starting to decline deposits so that they don’t have to impose negative rates, others have taken the plunge and are applying negative interest rates to deposits!

Section 49.5 The changing role of the treasurer

Technological developments have resulted in greater integration and automation in the management of a company’s cash, and have also facilitated the centralisation of the process.

Large groups appear to be centralising cash management as much as they possibly can (which has no impact outside the group). However, this was just a start, and many groups have now also started centralising trade payables. In Europe, thanks to SEPA, we are seeing the centralisation of both payables and receivables. This would be rather more difficult to set up as it requires the cooperation of customers who will have to send their payment, not to the company that has supplied it with the goods or services it has ordered, but to another company.

Some groups view cash management as a strategic function. Others see it as a complex administrative function that generates additional risks. Some large groups have, quite simply, outsourced the cash management function, either to banks or to consulting firms offering off-the-shelf solutions for outsourced cash management. However, since the early 2000s, there has also been an increase in the number of groups centralising their cash management.

With the development and greater security of the Internet, SMEs that do a lot of business on the international market have been able to set up efficient systems at a lower cost.