Chapter 35

Working out details: the design of the capital structure

Steering a course between Scylla and Charybdis

By way of conclusion to the part on capital structure policy, we would like to reflect once again on the thread that runs throughout this set of chapters: the choice of a source of financing.

We begin by restating for the reader an obvious truth that is too often forgotten: If the objective is value creation, then the choice of investments is much more important than the choice of capital structure. Because financial markets are liquid, situations of disequilibrium do not last. Arbitrage inevitably takes place to erase them. For this reason, it is very difficult to create value by issuing securities at a price higher than their value. In contrast, industrial markets are much more viscous. Regulatory, technological and other barriers make arbitrage – building a new plant, launching a rival product, and so on – far slower and harder to implement than on a financial market, where all it takes is a telephone call or an online order.

In other words, a company that has made investments at least as profitable as its providers of funds require will never have insurmountable financing problems. If need be, it can always restructure the liability side of its balance sheet and find new sources of funds. Inversely, a company whose assets are not sufficiently profitable will, sooner or later, have financing problems, even if it initially obtained financing on very favourable terms. How fast its financial position deteriorates will depend simply on the size of its debt.

Section 35.1 The major concepts

1. COST OF A SOURCE OF FINANCING

Several simple ideas can be stated in this context.

The required rate of return is basically independent of the method of financing and the nationality of the investor. It depends solely on the risk of the investment itself.

This presents the following consequences:

- it is generally not possible to link the financing to the investment;

- no “portfolio effect” can reduce this cost;

- only the bearing of systematic risk will be rewarded.

It is therefore shortsighted to choose a source of financing based on what it appears to cost. To do so is to forget that all sources of financing will cost the same, given the risk.

We have too often heard it said that the cost of a capital increase was low, because the dividend yield on the shares was low, that internal financing costs nothing, that convertible bonds can lower a company’s cost of financing, and so on. Statements of this kind confuse the accounting cost with the true financial cost.

A source of financing is a bargain only if, for whatever reason, it brings in more than its market value. A convertible bond can be a good deal for the issuer not because it carries a low coupon rate, but only if the option embedded in it can fetch more than its market value.

Let us dwell briefly on the error one commits by confusing apparent cost and true financial cost.

- The difference is minor for debt. It may arise from changes in market interest rates or, more rarely, from changes in default risk. In matters of financial organisation, debt has the merit that its accounting cost is close to its true cost; furthermore, that cost is visible on the books, since interest payments are an accounting expense.

- The error is greater for equity, inasmuch as the dividend yield on the share needs to be augmented for prospective growth.

- The error is extreme for internal financing, where, as we have seen, the apparent cost of reinvested cash flow is nil.

- The error is hard to evaluate for all forms of hybrid securities – and this is often the explanation for their success. But let the reader beware: the fact that such securities carry low yields does not mean their financial cost is low. As we have shown in the foregoing chapters, an analysis of the hybrid security using both present value and option valuation techniques is needed to identify the true cost of this financing source.

Debt, by virtue of the liability that it represents for timely payments of interest and principal, has a direct consequence on the company’s cash flow. Debt can plunge the company into the ditch if it runs into difficulties; on the other hand, it can turn out to be a turbocharger that enables the company to take off at high speed if it is successful.

| Source | Instrument | Theoretical cost to be used in investment valuation | Cost according to financial theory | Apparent or explicit cost (accountability, cash flow) | Difference | Determinants of the difference |

| (A) | (B) | (A)–(B) | ||||

| Debt | The same for all products, it is a function of the systematic (non-diversifiable) risk of the investment | Market rate at which the company can refinance | Contractual rate | Small | Evolution of market interest rates; evolution of default risk | |

| Equity | Share issue | Expected return required by the market on shares with the same risk profile | Nil in income statement; apparent cost measured by the return | Significant | Expected dividend growth rate | |

| Self-financing | Nil in the income statement; no apparent cost | Very significant | Total absence of apparent cost | |||

| Hybrid products | Convertible bonds | Yield to maturity + value of the conversion option | Low yield to maturity (restated according to IFRS) | Medium | Value of conversion option | |

| Preference shares | Return should be slightly lower than the ordinary shares | Higher than ordinary shares and fixed throughout the life of the instrument | Small | They are shares for which a part of the value is guaranteed (present value of fixed dividends) | ||

| Subordinated bonds | Rate higher than the cost of debt | Mostly linked to the periodical income | Variable according to results | Variability of results |

If a company is successful, the cost of a share issue will appear to be much higher, as shareholders will receive much higher dividends than they initially expected. They will notice, looking backwards, that the price of the share was cheap. On the contrary, if the firm is in financial distress, the cost of the share issue will be close to nil, as the company will not be able to pay the expected dividends. The same is rarely true for debt, as it only occurs if the firm’s financial distress leads debtholders to forgive part of their loans.

2. Is there a “once-and-for-all” optimal capital structure?

The answer is clear: no, the optimal capital structure is a firm-specific policy and changes across time.

At the same time, there are a few loose ideas on the subject that the reader will have absorbed. Otherwise, how could one explain why the notion of what constitutes a “good” or “balanced” capital structure should have “changed” so much, and so often, over the course of time?

- In the 1980s, a good capital structure needed to reflect a rebalancing of the structure of the business, characterised by gradual diminution of debt, improved profitability and heightened reliance on internal financing.

- In the early 1990s, in an environment of low investment and high real interest rates, there was no longer a choice: being in debt was not an option. Share buy-backs appear in Europe.

- In the late 1990s, though, debt was back in favour if used either to finance acquisitions or to reduce equity. The reason: nominal interest rates were at their lowest level in 30 years.

- The 2000s started with a financial crisis (the bursting of the Internet bubble) followed by an economic crisis that led to a closure of financial markets. This prevented firms from rebalancing their financial structure towards more equity. The lesson was learnt, as when the second economic crisis of the decade arrived in 2007–2008, corporates were lowly geared, except for groups involved in leveraged buyouts who suffered first. In all sectors, firms are trying to lower their debt level (by lowering capex and reducing working capital) to maintain flexibility as the timing of the upturn remains uncertain.

- In the middle of the 2010s, the companies which have hoarded cash launch share buy-back operations or distribute large dividends, sometimes even going back to external growth operations.

The great majority of companies had been paying down their debt for more than 10 years, thereby giving them considerable borrowing capacity they could use to get them through a difficult period.

Source: Datastream, Factset, Exane BNP Paribas – Euro Stoxx 50; S&P 100

3. Capital structure, inflation and growth

Because inflation is always a disequilibrium phenomenon, it is quite difficult to analyse from a financial standpoint. We can observe, however, that during a period of inflation and negative real interest rates, overinvestment and excessive borrowing lead to a general degradation of capital structures. Companies that invest, reap the benefit of inflated profits; adjusted for inflation, the cost of financing is low. Shareholders can benefit from this phenomenon as well: a low rate of return on investment will be offset by the low cost of financing.

Companies’ inclination to take on debt depends a great deal on the real interest rate and the real growth rate of the economy.

Source: INSEE, Factset

4. What is equity for?

Equity capital thus plays two roles. Its first function is, of course, to finance part of the investment in the business. Another purpose, just as important, though, is to serve as a guarantee to the company’s creditors who finance the other part of the investment. For this reason, the cost of equity includes a risk premium.

Whence the insurance aspect of equity capital (cf. discussion in Chapter 34 of equity as an option): like insurance, equity financing always costs too much until the crisis happens, in which case one is happy to have a lot of it. As we will see later, when a crisis does come, having considerable equity on the balance sheet gives a company time – time to survive and restructure when earnings are depressed, to introduce new products, to seize opportunities for external growth, and so on.

By comparison, a company with considerable debt suffers greatly because it has fixed expenses (interest payments) and fixed maturities (principal repayment) that will drag it down further.

The amount of equity capital in a business is also an indicator of the level of risk shareholders are willing to run. In a crisis, the companies with the most leverage are the first to disappear.

It is true also that financing geared towards equity does not lead management to react quickly when a crisis happens… and can sometimes mean that non-performing firms survive for a long time.

Section 35.2 How to choose a capital structure

Graham and Harvey (2001) surveyed top executives and finance directors to determine what criteria they use in taking a financing decision. According to their study, the tax saving on debt was not an essential criterion in the choice of capital structure, nor was fear of substantial bankruptcy costs. Rather, concern about downgrading of the company’s credit rating came top of the list. It is reassuring to see that the conclusions of the second Modigliani–Miller article (1963) are not prompting companies to focus on tax considerations in deciding whether or not to take on debt.

Even if companies say they have a fairly precise target for the level of their debt, more than half of all finance directors base their choice of financing on preserving flexibility. Although some theoreticians and some finance professors emphasise the limitations of EPS dilution as a criterion (it is not automatically synonymous with destruction of value), among practitioners it remains the most important factor in deciding whether or not to undertake a capital increase. This criterion seems to us a bit outmoded, but we will address it nonetheless in a following section.

The reader will by now have grasped that capital structure is the result of complex compromises between the following elements:

- need to keep flexibility, i.e. keeping some financing capacity in case positive events (investment opportunities) or negative events (crises) happen;

- need to maintain an adequate rating;

- lifecycle of the company and the economic characteristics of the company’s sector;

- risk aversion of shareholders and their wish not to be diluted;

- existence of opportunities or constraints on financial markets;

- the capital structure of competitors;

- and finally the character of management.

1. Financial flexibility

Having and retaining flexibility is of strong concern to finance directors. They know that the choice of financing is a problem to be evaluated over time, not just at a given moment; a choice today can reduce the spectrum of possibilities for another choice to be made tomorrow.

Thus, taking on debt now will reduce borrowing capacity in the future, when a major investment – perhaps foreseeable, perhaps not – may be needed. If borrowing capacity is used up, the company will have no choice but to raise fresh equity. From time to time, though, the primary market in equities is closed because of depressed share prices (or can be accessed at such high price conditions, as was the case at the end of 2008, that most issuers are discouraged from tapping this market). If this should be the case when the company needs funds, it may have to forego the investment.

True, the markets for high-yield debt securities react as the equity markets do and may at times be closed to new issues or, equally, require such high interest rates that they are de facto closed.

Raising money today with a share issue, however, does not preclude another capital increase at a later time. Moreover, an equity financing today will increase the borrowing capacity that can be mobilised tomorrow.

The desire to retain flexibility prompts the company to carry less debt than the maximum level it deems bearable, so that it will at all times be in a position to take advantage of unexpected investment opportunities. Here again, we find the option concept applied to corporate finance.

In addition, the CFO will have taken pains to negotiate undrawn lines of credit with the company’s bank; to have in hand all the shareholder authorisations needed to issue new debt or equity securities; and to have effective corporate communication on financial matters with rating agencies, financial analysts and investors.

Going beyond the debt–equity dichotomy, the quest for financial flexibility will require the CFO to open up different capital markets to the company. A company that has already issued securities on the bond market and keeps a dialogue going with bond investors can come back to this market very quickly if an investment opportunity appears.

The proliferation of financing sources – bilateral or syndicated bank loans, securitised receivables, factoring schemes, bonds, convertibles, shares, and so on – allows the company to enhance its financial flexibility even further.

2. The rating of the company

Ratings agencies have clearly gained in importance – especially in Europe – due mostly to the transition from an economy based mostly on banking intermediaries to one where the financial markets are becoming predominant.

Ratings are becoming one of the main concerns of CFOs. Financial decisions are thus frequently taken based partly on their rating impact; or, more precisely, decisions having a negative rating impact will be adjusted accordingly. Some companies even set rating targets (Pepsi, Diageo and Vivendi, for example). This can seem paradoxical in two ways:

- although all financial communication is based on creating shareholder value, companies are much less likely to set share price targets than rating targets;

- in setting rating targets, companies have a new objective: that of preserving value for bondholders! This is praiseworthy and, in a financial market context, understandable, but has never been part of the bargain with shareholders.

We see several possible explanations for this paradox. First of all, a debt rating downgrade is clearly a major event for a group and goes well beyond bondholder information. A downgrade is traumatic and messy and almost always leads to a fall in the share price. So, in seeking to preserve a financial rating, it is also shareholder value that management is protecting, at least in the short term.

A downgrade can also have an immediate cost if the company has issued a bond with a step-up in the coupon, i.e. a clause stating that the coupon will be increased in the event of a rating downgrade.

A good debt rating guarantees a higher degree of financial flexibility. The higher the rating, the easier it is to tap the bond markets, as transactions are less dependent on market fluctuations. An investment grade company, for example, can almost always issue bonds, whereas market windows close regularly for companies that are below investment grade.

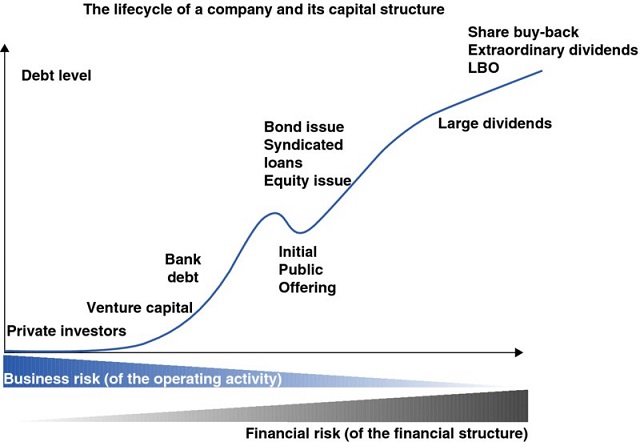

3. Lifecycle of the company and the economic characteristics of the company’s sector

A start-up will have a hard time getting any debt financing. It has no past and thus no credit history, and it generally has no tangible assets to pledge as security. The technological environment around it is probably quite unsettled, and its free cash flow is going to be negative for some time. For a lender, the level of specific risk is very high. The start-up consequently has no choice but to seek equity financing.

At the other extreme, an established company in a market that has been around for years and is reaching maturity will have no difficulty attracting lenders. Its credit history is there, its assets are real and it is generating free cash flows (predictable with low forecast error), which are all the greater if the major investments have already been made. In short, it has everything a creditor craves. In contrast, an equity investor will find little to be enthusiastic about: not much growth, not much risk, thus not much profitability.

Similarly, in an industry with high fixed costs, a company will seek to finance itself mostly with equity, so as not to pile the fixed costs of debt (interest payments) on top of its fixed operating costs and to reduce its sensitivity to cyclical downswings. But sectors with high fixed costs – steel, cement, paper, energy, telecoms, etc. – are generally highly capital-intensive and thus require large investments, inevitably implying borrowing as well.

An industry such as retailing with high variable costs, on the other hand, can make the bet that debt entails, as the fixed costs of borrowing come on top of low fixed operating costs.

Lastly, the nature of the asset can influence the availability of financing to acquire it. A highly specific asset — that is, one with little value outside of a given production process — will be hard to finance with debt. Lenders will fear that if the company goes under, the asset’s market value will not be sufficient to pay off their claims.

In their study, Frank and Goyal (2009) put forward six factors that have an impact on the debt level of a firm. The first factor is the business sector. The others are the proportion of fixed assets, the level of earnings, the size, the price-to-book and inflation. They show that the bigger the company, the higher the debt level.

Source: Datastream, Exane – Euro Stoxx 50; S&P 100.

4. Shareholder preferences

If the company’s shareholder base is made up of influential shareholders, majority or minority, their viewpoints will certainly have an impact on financing choices.

Some holders will block share issues that would dilute their stake because they are unable to take up their share of the rights. A company in this situation must then go deeply into debt. Others may have a marked aversion to debt because they have no desire to increase the level of risk they are bearing.

The most ambitious shareholders will accept both dilution of their control and risk linked to a high level of debt. Their control and the survival of the firm will only be possible thanks to the success of the strategy (Pernod Ricard, for example).

5. Opportunities

Since markets are not systematically in equilibrium, opportunities can arise at a given moment. A steep run-up in share prices will enable a company to undergo a capital increase on the cheap (by selling shares at a very high price). The folly of a bank that says yes to every loan application and the sudden infatuation of investors for a particular kind of stock (renewable energy companies in 2005–2008, Hong Kong listings in 2010–2011, start-ups listing on the stock exchange at the beginning of 2014), a high volatility together with a limited volume of new issues making the issue of convertible bonds attractive are other examples.

Furthermore, if the company at some point in time is enjoying exceptionally low-cost financing, investors, for their part, will have made a bad mistake. In their fury, they risk tarnishing the company’s image, and it will be a long time before they can be counted on to put up new money. The start-up that went public on the stock market in the first semester of 2014, benefiting from the small caps/start-ups frenzy, will surely have raised money at low cost, but how will it raise more capital a year later, after its share price has fallen by 70%?

6. Capital structure of competitors

To have higher net debt than one’s rivals is to bet heavily on the company’s future profitability – that is, on the economy, the strategy, and so forth. It is therefore to be more vulnerable to a cyclical downturn, one that could lead to a shake-out in the sector and extinction of the weakest.

Experience shows that business leaders are loath to imperil an industrial strategy by adopting a financing policy substantially different from their competitors’. If they have to take risks, they want them to be industrial or commercial risks, not financial risks.

With the analyses in hand, the person or body taking the financing decision will be able to do so with full knowledge of the facts. The investor will bear in mind that, statistically (and thus for his diversified portfolio), his dream of multiplying his wealth through judicious use of debt will be the nightmare of the company in financial distress. The financial success of a few tends to make one forget the failure of companies that did not survive because they were too much in debt.

7. Managers’ character

The character of managers will materially influence the capital structure of the firm. Managers averse to risk choose a capital structure with low leverage, whereas those with high self-confidence adopt a highly geared financial structure. Malmendier et al. (2011) have shown that managers who experienced the Great Depreciation favour self-financing and are very prudent towards raising debt.

This may seem obvious, but it reminds us that choices in corporate finance can be highly subjective; behavioural finance is not to be underestimated.

Section 35.3 Effects of the financing choice on accounting and financial criteria

With this description of the key ideas in mind, the time has come for the reader to implement a choice of capital structure as part of a financing plan. To this end, we suggest that the following documents be at hand:

- past financial statements: income statements, balance sheets, cash flow statements;

- forecast financial statements and financing plan, constructed in the same form as past cash flow statements. These can either be mean forecasts or simulations based on several assumptions; the latter strikes us as the better solution. A simulation model will be very useful for establishing the probable future course of the company’s capital structure, profitability, business conditions, and so on, given a set of assumptions. This kind of exercise is facilitated by using spreadsheet software and simulation assumptions that allow for a dynamic analysis;

- to be fully prepared, the analyst will also want to have sector average ratios, which can be obtained from various industry studies.

1. Impact on liquidity

The liquidity of the company is its ability to meet its financial obligations on time in the ordinary course of business, obtain new sources of financing and thereby ensure balance at all times between its income and expenditure.

In a truly serious financial crisis, companies can no longer obtain the financing they need, no matter how good they are. This is the case in a crash brought on by a panic. It is not possible to protect oneself against this risk, which fortunately is altogether exceptional. The more common liquidity risk occurs when a company is in trouble and can no longer issue securities that financial markets or banks will accept; investors have no confidence in the company at all, regardless of the merit of its investment projects.

Liquidity is therefore related to the term structure of financial resources. It is analysed both at the short-term level and at the level of repayment capacity for medium- and long-term debt. This leads to the use of traditional concepts and ratios that we have already seen: working capital, equity, debt, current assets/current liabilities, and so on.

For analysing the impact on liquidity, the simulation must bear on free cash flows. The analyst will need to simulate different levels of debt and repayment terms and test whether free cash flows are sufficient to pay off the borrowings without having to reschedule them. This is also a method used by rating agencies to determine their rating and by bankers to assess whether they want to lend to a firm or not.

If the company bears a high level of debt, the analyst will consider worst-case scenarios to assess when the liquidity situation will become critical. The analyst will then be focused on the volatility of free cash flows compared to the central scenario.

2. Impact on solvency

Debt increases the company’s risk of becoming insolvent. We refer the reader to the development of this topic in Chapter 14.

3. Impact on earnings

Indeed, interest payments constitute a fixed cost that cannot be reduced except by renegotiating the terms of the loan or filing for bankruptcy. Take, as an example, a company with fixed costs of 40 and variable costs of 0.5 per unit sold. If the selling price is 1, the breakeven point is 80 units. If the company finances an investment of 50 with debt at 4%, the breakeven point rises to 84 units because fixed costs have increased by 2 (interest expense on the borrowing). If the investment is financed with equity, the breakeven point stays at 80.

The problem is trickier when the interest rate is indexed to market rates but the interest payments are still a fixed cost in the sense of being independent of the level of activity. Typically, interest rates rise when general economic activity is weakening. In such a case, it is important to test the sensitivity of the company’s earnings to changes in interest rates.

4. Impact on return on equity

For a company with no debt, the return on equity is equal to the rate of return on capital employed. For a company with debt, one must add to the former a supplement (sometimes negative) for the effect of financial leverage (the difference between ROCE and cost of debt, multiplied by the debt–equity ratio; see Chapter 14).

The analysis of the return on equity must therefore distinguish the part due to the economic return on capital employed from the part due to leverage. However, a static analysis is not sufficient. What is needed is to determine the sensitivity of return on equity to any change in financial leverage, cost of debt or return on capital employed.

5. Impact on earnings per share

An investment financed by debt increases the company’s net profit, and thus earnings per share, only if the after-tax return generated by its investments is greater than the after-tax cost of debt. If this is not the case, the company should not make the investment. If an investment is particularly sizeable and long-term, it may happen that its rate of return is less than the cost of debt for a period of time, but this must be a temporary situation.

To study these phenomena, companies are accustomed to analysing changes in earnings per share relative to operating profit (EBIT).

| Period 1 | Period 2 | ||||

| Period 0 | Case A | Case B | Case A | Case B | |

| Operating profit (EBIT) | 300 | 300 | 300 | 370 | 370 |

| − Interest expense at 6% | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 12 |

| = Pre-tax profit | 300 | 300 | 288 | 370 | 358 |

| − Income tax at 35% | 105 | 105 | 101 | 130 | 125 |

| = Net profit | 195 | 195 | 187 | 242 | 233 |

| Number of shares | 100 | 120 | 100 | 120 | 100 |

| Earnings per share | 1.95 | 1.62 | 1.87 | 1.85 | 2.33 |

In period 2, earnings per share will be greater if the investment is financed by debt. In case B, the interest expense reduces EPS, but by less than the dilution due to the capital increase in case A.

This conclusion cannot be generalised, however. The following chart simulates various levels of EPS as a function of operating profit in period 2.

In short: beware! The faster growth of EPS with debt financing is a purely arithmetic result; it does not indicate greater value creation. It is due simply to the leverage effect, the counterpart of which is a higher level of risk to the shareholder.

The reader will be able to verify that if operating profit is less than 340, the preceding assertion is reversed. However, a steep decline in earnings is required to produce this result.