Chapter 20

Bonds

Fixing the interest

A debt security is a financial instrument representing the borrower’s obligation to the lender from whom he has received funds. If the maturity of the security is over one year, it will be called a bond.

This obligation provides for a schedule of cash flows defining the terms of repayment of the funds and the lender’s remuneration in the interval. The remuneration may be fixed during the life of the debt or floating if it is linked to a benchmark or index.

Unlike conventional bank loans, debt securities can be traded on secondary markets (stock exchanges, money markets, mortgage markets and interbank markets), but their logic is the same and all the reasoning presented in this chapter also applies for bank loans. Debt securities are bonds, commercial paper, Treasury bills and notes, certificates of deposit and mortgage-backed bonds or mortgage bonds. Furthermore, the current trend is to securitise loans to make them negotiable.

Disintermediation was not the only factor fuelling the growth of bond markets. The increasing difficulty of obtaining bank loans was another, as banks realised that the interest margin on such loans did not offer sufficient return on equity. This pushed companies to turn to bond markets to raise the funds that banks had become reluctant to advance. The increasingly burdensome solvency and liquidity constraints imposed on banks (Basel III and IV) should increase the share of financing insured by the debt capital markets even further.

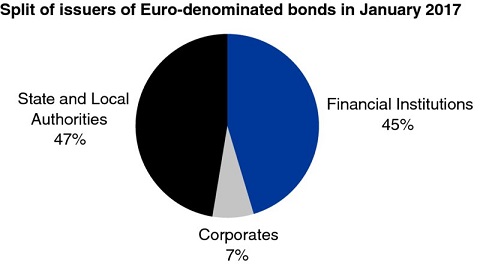

Companies accounted for 7% of euro-denominated bonds outstanding in 2017.

Source: European Central Bank

Investors have welcomed the emergence of corporate bonds offering higher yields than government bonds. Of course, these higher returns come at the cost of higher risks.

Many of the explanations and examples offered in this chapter deal with bonds, but they can easily be applied to all kinds of debt instruments. We shall take the example of the easyJet February 2023 bond issue with the following features:

Section 20.1 Basic concepts

1. The principal

(a) Nominal or face value

Loans that can be publicly traded are divided into a certain number of units giving the same rights for the same fraction of the debt. The nominal, face or par value is €100 000 in the easyJet case.

The nominal value is used to calculate the interest payments. In the simplest cases, it equals the amount of money the issuer received for each bond and that the issuer will repay upon redemption.

(b) Issue price

The issue price is the price at which the bonds are issued; that is, the price investors pay for each bond. The easyJet bond was issued on 9 February 2016 at a price of €99 850, i.e. 99.85% of its face value.

Depending on the characteristics of the issue, the issue price may be higher than the face value (issued at a premium), lower than the face value (issued at a discount) or equal to the face value (at par, which is the case for the easyJet issue).

(c) Redemption

When a loan is amortised, it is said to be redeemed. In Chapter 17 we looked at the various ways a loan can be repaid:

- redemption at maturity, or on a bullet repayment basis. This is the case in the easyJet issue;

- redemption in equal slices (or series), or constant amortisation;

- redemption in fixed instalments.

Other methods exist, such as determining which bonds are redeemed by lottery… there is no end to financial creativity!

A deferred redemption period is a grace period, generally at the beginning of the bond’s life, during which the issuer does not have to repay the principal.

The terms of the issue may also include provisions for early redemption (call options) or retraction (put options). A call option gives the issuer the right to buy back all or part of the issue prior to the maturity date, while a put option allows the bondholder to demand early repayment.

A redemption premium or discount arises where the redemption value is higher or lower than the nominal value.

(d) Maturity of the bond

The life of a bond extends from its issue date to its final redemption date. Where the bond is redeemed in several instalments, the average maturity of the bond corresponds to the average of each of the repayment periods.

where t is the variable for the year and N the total number of periods.

The easyJet bonds have a maturity of seven years.

(e) Guarantees

Repayment of the principal (and interest) on a bond borrowing can be guaranteed by the issuer, the parent company and less often for corporates by collateral (i.e. mortgages), pledges or warranties. Bonds are rarely secured, while commercial paper and certificates of deposit can, in theory, be secured but in fact never are.

The bonds issued by easyJet plc benefit from the guarantee provided by easyJet Airline Company Ltd.

2. Income

(a) Issue date

The issue date is the date on which interest begins to accrue. It may or may not coincide with the settlement date, when investors actually pay for the bonds purchased.

Interest on the easyJet bond begins to accrue on the settlement date.

(b) Interest rate

The coupon or nominal rate is used to calculate the interest (or coupon, in the case of a bond) payable to the lenders. Interest is calculated by multiplying the nominal rate by the nominal or par value of the bond.

On the easyJet issue, the coupon rate is 1.75% and the coupon payment is €1750.

In addition to coupon payments, investors may also gain additional remuneration if the issue price is lower than the par value.

(c) Periodicity of coupon payments

Coupon payments can be made every year, half-year, quarter, month or even more frequently. On certain borrowings, the interval is longer, since the total compounded interest earned is paid only upon redemption. Such bonds are called zero-coupon bonds.

In some cases, the interest is prepaid; that is, the company pays the interest at the beginning of the period to which it relates. In general, however, the accrued interest is paid at the end of the period to which it relates.

The easyJet issue pays accrued interest on an annual basis.

Section 20.2 The yield to maturity

The actual return on an investment (or the cost of a loan for the borrower) depends on a number of factors: the difference between the settlement date and the issue date, the issue premium/discount, the redemption premium/discount, the deferred redemption period and the coupon payment interval. As a result, the nominal rate is not very meaningful.

We have seen that the yield to maturity (Chapter 17) cancels out the bond’s present net value; that is, the difference between the issue price and the present value of future flows on the bond. Note that for bonds, the yield to maturity (y) and the internal rate of return are identical. This yield is calculated on the settlement date when investors pay for their bonds, and is always indicated in the prospectus for bond issues. The yield to maturity takes into account any timing differences between the right to receive income and the actual cash payment.

In the case of the easyJet bond issue:

The yield to maturity, before taxation and intermediaries’ fees, represents:

- for investors, the rate of return they would receive by holding the bonds until maturity, assuming that the interest payments are reinvested at the same yield to maturity, which is a very strong assumption;

- for the issuer, the pre-tax actuarial cost of the loan.

From the point of view of the investor, the bond schedule must take into account intermediation costs and the tax status of the income earned. For the issuer, the gross cost to maturity is higher because of the commissions paid to intermediaries. This increases the actuarial cost of the borrowing. In addition, the issuer pays the intermediaries (paying agents) in charge of paying the interest and reimbursing the principal. Lastly, the issuer can deduct the coupon payments from its corporate income tax, thus reducing the actual cost of the loan.

1. Spreads

The spread is the difference between the rate of return on a bond and that on a benchmark used by the market. In the euro area, the benchmark for long-term debt is most often the interest rate swap (IRS) rate; sometimes the spread to government bond yields is also mentioned. For floating-rate bonds and bank loans (which are most often with floating rates), the spread is measured to a short-term rate, the three- or six-month Euribor in the eurozone.

The easyJet bond was issued with a spread of 147 basis points (1.47%) to mid swap rate, meaning that easyJet had to pay 1.47% more per year than the risk-free rate to raise funds.

The spread is a key parameter for valuing bonds, particularly at the time of issue. It depends on the perceived credit quality of the issuer and the maturity of the issue, which are reflected in the credit rating and the guarantees given. Spreads are, of course, a relative concept, depending on the bonds being compared. The stronger the creditworthiness of the issuer and the market’s appetite for risk, the lower the margin will be.1

2. The secondary market

Once the subscription period is over, the price at which the bonds were sold (their issue price) becomes a thing of the past. The value of the instrument begins to fluctuate on the secondary market. Consequently, the yield to maturity published in the prospectus applies only at the time of issue; after that, it fluctuates in step with the value of the bond.

Theoretically, changes in the bond’s yield to maturity on the secondary market do not directly concern the borrower, since the cost of the debt was fixed when it was contracted.

Spreads tend to widen markedly during a crisis (like in 2008–2010), both in absolute terms and relative to each other.

Source: Datastream/Factset

The situation of European countries during the euro crisis has generated some peculiar cases whereby, for example, the German government could borrow at negative interest rates.

Source: Datastream/Factset

For the borrower, the yield on the secondary market is merely an opportunity cost; that is, the cost of refunding for issuing new bonds. It represents the “real” cost of debt, but is not shown in the company accounts where the debt is recorded at its historical cost, regardless of any fluctuations in its value on the secondary market. The market value of debt can only be found in the notes to IFRS accounts.

3. Listing techniques

The price of bonds listed on stock markets is expressed as a percentage of the nominal value. In fact, they are treated as though the nominal value of each bond were €100. Thus, a bond with a nominal value of €50 000 will not be listed at €49 500 but at 99% (49 500/50 000 × 100). Similarly, a bond with a nominal value of €10 000 will be listed at 99%, rather than €9900. This makes it easier to compare bond prices.

For the comparison to be relevant, the prices must not include the fraction of annual interest already accrued. Otherwise, the price of a bond with a 15% coupon would be 115 just before its coupon payment date and 100 just after. This is why bonds are quoted net of accrued interest. Bond tables thus show both the price expressed as a percentage of the nominal value and the fraction of accrued interest, which is also given as a percentage of the nominal value.

On 7 April 2016, the easyJet bond traded at 104.890% with 0.288% accrued interest. Buying the easyJet bond then would have cost (excl. any trading fee or tax) €105 178: €100 000 × (104.890% + 0.288%).

Certain debt securities, mainly fixed-rate Treasury notes with annual interest payments, are quoted at their yield to maturity. The two listing methods are rigorously equivalent and only require a simple calculation to switch from one to the other.

By now you have probably realised that the price of a bond does not reflect its actual cost. A bond trading at 105% may be more or less expensive than a bond trading at 96%. The yield to maturity is the most important criterion, allowing investors to evaluate various investment opportunities according to the degree of risk they are willing to accept and the length of their investment. However, it merely offers a temporary estimate of the promised return; this may be different from the expected return, which incorporates the probability of default of the bond.

4. Further issues and assimilation

Having made one bond issue, the same company can later issue other bonds with the same features (time to maturity, coupon rate, coupon payment schedule, redemption price and guarantees, etc.), so that they are interchangeable. This enables the various issues to be grouped as one for a larger total amount. Assimilation makes it possible to reduce administrative expenses and enhance liquidity on the secondary market.

Nevertheless, the drawback for the issuer is that it concentrates maturity on one date, which is not in line with sound financial policy.

Bonds assimilated are issued with the same features as the bonds with which they are interchangeable. The only difference is in the issue price,2 which is shaped by market conditions that are very likely to have changed since the original issue.

Section 20.3 Floating-rate bonds

So far we have looked only at fixed-income debt securities. The cash flow schedule for these securities is laid down clearly when they are issued, whereas the securities that we will be describing in this section give rise to cash flows that are not totally fixed from the very outset, but follow preset rules.

Source: Dealogic

1. The mechanics of the coupon

The coupon of a floating-rate bond (floating rate note, FRN or “floats”) is not fixed, but is indexed to an observable market rate, generally a short-term rate, such as a six-month Euribor. In other words, the coupon rate is periodically reset based on some reference rate plus a spread. When each coupon is presented for payment, its value is calculated as a function of the market rate, based on the formula:

This cancels out the interest rate risk, since the issuer of the security is certain of paying interest at exactly the market rate at all times. Likewise, the investor is assured at all times of receiving a return in line with the market rate. Consequently, there is no reason for the price of a variable-rate bond to move very far from its par value unless the issuer’s solvency becomes a concern.

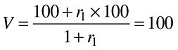

Let’s take the simple example of a fixed-rate bond indexed to the one-year rate that pays interest annually. On the day following payment of the coupon and in the year prior to its maturity date, the price of the bond can be calculated as follows (as a percentage of par value):

where r 1 is the one-year rate.

Here the price of the bond is 100%, since the discount rate is the same as the rate used to calculate the coupon. Likewise, we could demonstrate that the price of the bond is 100% on each coupon payment date. The price of the bond will fluctuate in the same way as a short-term instrument in between coupon payment dates.

If the reference rate covers a period which is not the same as the interval between two coupon payments, then the situation becomes slightly more complex. That said, since there is rarely a big difference between short-term rates, the price of the bond will clearly not fluctuate much over time.

The main factor that can push the price of a variable-rate bond well below its par value is a deterioration in the solvency of the issuer.

2. The spread

Like those issuing fixed-rate securities, companies issuing floating-rate securities need to pay investors a return that covers the counterparty (credit) risk. Consequently, a fixed margin (spread) is added to the variable percentage when the coupon is calculated. For instance, a company may issue a bond at three-month Euribor + 0.45% (or 45 basis points). The size of this margin basically depends on the company’s financial creditworthiness.

The spread is set once and for all when the bond is issued, but of course the company’s risk profile may vary over time. This factor, which does not depend on interest rate trends, slightly increases the volatility of variable-debt securities.

The issue of credit risk is the same for a fixed-rate security as for a variable-income security.

3. Index-linked securities

Floating rates, as described in the first paragraph of this section, are indexed to a market interest rate. Broadly speaking, however, a bond’s coupons may be indexed to any index or price provided that it is clearly defined from a contractual standpoint. Such securities are known as index-linked securities.

For instance, most European countries have issued bonds indexed to inflation. The coupon paid each year, as well as the redemption price, is reset to take into account the rise in the price index since the bond was launched. As a result, the investor benefits from complete protection against inflation. With the advent of the euro, for example, the UK government issued a bond indexed to the rate of inflation in the UK. Likewise, Mexican companies have brought to market bonds linked to oil prices, while other companies have issued bonds indexed to their own share price.

To value this type of security, projections need to be made about the future value of the underlying index, which is never an easy task.

The following table shows the main reference rates in Europe.

REFERENCE RATES IN EUROPE

| Reference rate | Definition | As at April 2017 |

| EONIA (Euro Overnight Index Average) | European money-market rate. This is an average rate weighted by overnight transactions reported by a representative sample of European banks. Computed by the European Central Bank and published by Reuters. | −0.360% |

| EURIBOR (European Interbank Offered Rate) | European money-market rate corresponding to the arithmetic mean of offered rates on the European banking market for a given maturity (between 1 week and 12 months). Sponsored by the European Banking Federation and published by Reuters, it is based on daily quotes provided by 64 European banks. | −0.331% (3 months) |

| LIBOR (London Interbank Offered Rate) | Money-market rate observed in London corresponding to the arithmetic mean of offered rates on the London banking market for a given maturity (between 1 and 12 months) and a given currency (euro, sterling, dollar, etc.). | −0.376% (euro 3 months) |

| IRS | The IRS rate indicates the fixed interest rate that will equate the present value of the fixed-rate payments with the present value of the floating-rate payments in an interest rate swap contract. The convention in the market is for the swap market makers to set the floating leg – normally at Euribor – and then quote the fixed rate that is payable for that maturity. |

Section 20.4 Socially responsible bonds

Green bonds are, from a purely financial point of view, standard bonds. Their green status comes from the commitment that the issuer makes to use the funds raised to finance positive projects for the environment (as defined by the firm, generally together with the assistance of an independent consultant).

Monitoring spending on a specific use requires an organisation that is not typical for the finance department. This has a cost. When investors are not ready to acquire green bonds at a higher price than traditional bonds (which is often the case), this induces a higher cost for the firm. Green bonds are (even though companies sometimes deny this) a communication tool. A number of green bond issuers are active in sectors that are not typically environmentally friendly: energy (EDF, Engie); automotive (Toyota).

Volumes of issues are growing rapidly but remain relatively modest (10%) in the overall bond market.

In the same spirit as green bonds, some issuers have issued social bonds to finance projects or, more generally, sustainability bonds.

Section 20.5 The volatility of debt securities

The holder of a debt security may have regarded himself as protected having chosen this type of security, but he actually faces three types of risk:

- interest rate risk and coupon reinvestment risk, which affect almost solely fixed-rate securities;

- credit risk, which affects fixed-rate and variable-rate securities alike. We will consider this at greater length in the following section.

1. Changes in the price of a fixed-rate bond caused by interest rate fluctuations

(a) Definition

What would happen if, at the end of the subscription period for the easyJet 1.75% bond, the market interest rate rose to 2.25% (scenario 1) or fell to 1.25% (scenario 2)? In the first scenario, the bondholder would obviously attempt to sell the easyJet bond to buy securities yielding 2.25%. The price of the bond would fall such that the bond offered its buyer a yield to maturity of 2.25%. Conversely, if the market rate fell to 1.25%, holders of the easyJet bond would hold onto their bonds, which yield 1.75%, while the market interest rate for the same risk level is now 1.25%. Other investors would attempt to buy them, and the price of the bond would rise to a level at which the bond offered its buyer a yield to maturity of 1.25%.

An upward (or downward) change in interest rates therefore leads to a fall (or rise) in the present value of a fixed-rate bond, irrespective of the issuer’s financial condition.

As we have seen, if the yield on our easyJet bond is 1.75%, its price is 100%.

But if its yield to maturity rises to 2.25% (a 0.5 point increase), its price will change to:

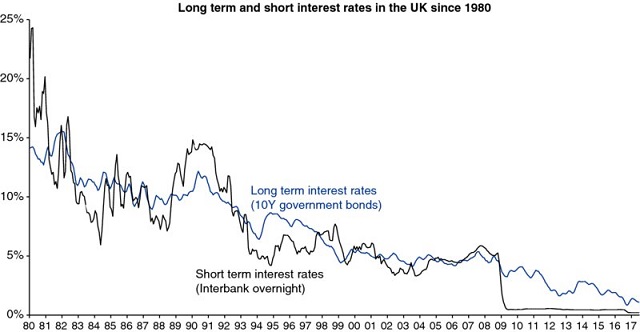

This shows that holders of bonds face a risk to their capital, and this risk is by no means merely theoretical given the fluctuations in interest rates over the medium term.

Source: Datastream/Bank of England

(b) Measures: modified duration and convexity

The modified duration of a bond measures the percentage change in its price for a given change in interest rates. The price of a bond with a modified duration of 4 will increase by 4% when interest rates fall from 7% to 6%, while the price of another bond with a modified duration of 3 will increase by just 3%.

From a mathematical standpoint, modified duration can be defined as the absolute value of the first derivative of a bond’s price with respect to interest rates, divided by the price:

where r is the market rate and Ft the cash flows generated by the bond.

Turning back to the example of the easyJet bond at its issuance date, we arrive at a modified duration of 6.535.

Modified duration is therefore a way of calculating the percentage change in the price of a bond for a given change in interest rates. It simply involves multiplying the change in interest rates by the bond’s modified duration. A rise in interest rates from 1.75% to 2.25% therefore leads to a price decrease of 0.5% × 6.535 = 3.267%, i.e. from 100% to 100 × (1 − 3.267%) = 96.733%.

We note a discrepancy of 0.062% with the price calculated previously (96.795%). Modified duration is valid solely at the point where it is calculated (i.e. 1.75% here). The further we move away from this point, the more skewed it becomes. For instance, at a yield of 2.25% it is 6.494 rather than 6.535. This will skew calculation of the new price of the bond, but the distortion will be small if the fluctuation in interest rates is also limited in size. From a geometrical standpoint, the modified duration is the first derivative of price with respect to interest rates and it reflects the slope of the tangent to the price/yield curve. Since this forms part of a hyperbolic curve, the slope of the tangent is not constant and moves in line with interest rates.

(c) Parameters influencing modified duration

Let’s consider the following three bonds:

| Bond | A | B | C |

| Coupon | 5% | 5% | 0% |

| Price | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Yield to maturity | 5% | 5% | 5% |

| Redemption price | 100 | 100 | 432.2 |

| Residual life | 5 years | 15 years | 30 years |

How much are these bonds worth in the event of interest rate fluctuations?

| Market interest rates (%) | A | B | C |

| 1 | 119.4 | 155.5 | 320.7 |

| 5 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 10 | 81.0 | 62.0 | 24.8 |

| 15 | 66.5 | 41.5 | 6.5 |

Note that the longer the maturity of a bond, the greater its sensitivity to a change in interest rates.

Modified duration is primarily a function of the maturity date. The closer a bond gets to its maturity date, the closer its price moves towards its redemption value and the more its sensitivity to interest rates decreases. Conversely, the longer it is until the bond matures, the greater its sensitivity to interest rate fluctuations.

Modified duration also depends on two other parameters, which are nonetheless of secondary importance to the time-to-maturity factor:

- the bond’s coupon rate: the lower the coupon rate, the higher its modified duration;

- market rates: the lower the level of market rates, the higher a bond’s modified duration.

Modified duration represents an investment tool used systematically by fixed-income portfolio managers. If they anticipate a decline in interest rates, they opt for bonds with a higher modified duration, i.e. a longer time to maturity and a very low coupon rate, or even zero-coupon bonds, to maximise their capital gains.

Conversely, if portfolio managers expect a rise in interest rates, they focus on bonds with a low modified duration (i.e. due to mature shortly and carrying a high coupon) in order to minimise their capital losses.

Convexity is the second derivative of price with respect to interest rates. It measures the relative change in a bond’s modified duration for a small fluctuation in interest rates. Convexity expresses the speed of appreciation or the sluggishness of depreciation in the price of the bond if interest rates decline or rise.

2. Coupon reinvestment risk

As we have seen, the holder of a bond does not know at what rate its coupons will be reinvested throughout the bond’s lifetime. Only zero-coupon bonds afford protection against this risk, simply because they do not carry any coupons!

First of all, note that this risk factor is the mirror image of the previous one. If interest rates rise, then the investor suffers a capital loss but is able to reinvest coupon payments at a higher rate than the initial yield to maturity. Conversely, a fall in interest rates leads to a loss on the reinvestment of coupons and to a capital gain.

Intuitively, it seems clear that for any fixed-income debt portfolio or security, there is a period over which:

- the loss on the reinvestment of coupons will be offset by the capital gain on the sale of the bond if interest rates decline;

- the gain on the reinvestment of coupons will be offset by the capital loss on the sale of the bond if interest rates rise.

All in all, once this period ends, the overall value of the portfolio (i.e. bonds plus reinvested coupons) is the same, and the investors will have achieved a return on investment identical to the yield to maturity indicated when the bond was issued.

In such circumstances, the portfolio is said to be immunised, i.e. it is protected against the risk of fluctuations in interest rates (capital risk and coupon reinvestment risk). This time period is known as the duration of a bond. It may be calculated at any time, either at issue or throughout the whole life of the bond.

For instance, an investor who wants to be assured of achieving a certain return on investment over a period of three years will choose a portfolio of debt securities with a duration of three years.

Note that the duration of a zero-coupon bond is equal to its remaining life.

In mathematical terms, duration is calculated as follows:

Duration can be regarded as being akin to the discounted average life of all the cash flows of a bond (i.e. interest and capital). The numerator comprises the discounted cash flows weighted by the number of years to maturity, while the denominator reflects the present value of the debt.

The easyJet bond has a duration of 6.64 years at issue.

We can see that 6.535 × (1 + 1.75%) = 6.64 years.

Turning our attention back to modified duration, we can say that it is explained by the duration of a bond, which brings together in a single concept the various determinants of modified duration, i.e. time to maturity, coupon rate and market rates.

Section 20.6 Default risk and the role of rating

Default risk can be measured on the basis of a traditional financial analysis of the borrower’s situation or by using credit scoring, as we saw in Chapter 08. Specialised agencies, which analyse the risk of default, issue ratings which reflect the quality of the borrower’s signature. There are three agencies that dominate the market – Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s and Fitch – but with the rise of a debt capital market for mid-sized companies, new rating agencies have emerged (e.g. Spread Research, Scope Credit Rating).

Rating agencies provide ratings for companies, banks, sovereign states and municipalities. They can decide to rate a specific issue or to give an absolute rating for the issuer (rating given to first-ranking debt). Rating agencies also distinguish between short- and long-term prospects.

Some examples of short-term debt ratings:

| Moody’s | Standard & Poor’s and Fitch | Definition | Examples (July 2017) |

| Prime 1 | A–1 | Superior ability to meet obligations | Sanofi, Nestlé, France |

| Prime 2 | A–2 | Strong ability to repay obligations | Deutsche Telekom, Santander |

| Prime 3 | A–3 | Acceptable ability to repay obligations | Pernod Ricard, Morocco |

| Not Prime | B | Speculative | Senegal, ArcelorMittal |

| C | Vulnerable | Venezuela | |

| D | Insolvent |

Some examples of long-term debt ratings:

| Moody’s | Standard & Poor’s and Fitch | Definition | Examples (July 2017) |

| Aaa | AAA | Best quality, lowest risk | Germany, Johnson & Johnson, Microsoft |

| Aa | AA | High quality. Very strong ability to meet payment obligations | Nestlé, Austria, Sanofi, Apple |

| A | A | Upper-medium grade. Issuer has strong capacity to meet its obligations | BASF, BNP Paribas, LVMH, Ireland |

| Baa | BBB | Medium grade. Issuer has satisfactory capacity to meet its obligations | Morocco, Vivendi, Telefónica |

| Ba | BB | Speculative. Uncertainty of issuer’s capacity to meet its obligations | Tereos, Portugal, Attijariwafa Bank |

| B | B | Issuer has poor capacity to meet its obligations | Banijay, Congo, Europcar |

| Caa | CCC | Poor standing. Danger with respect to payment of interest and return of principal | Sears, Venezuela, CMA CGM |

| Ca | CC | Highly speculative. Often in default | |

| C | C | Close to insolvency | |

| D or SD | Insolvent! | CGG |

Rating services also add an outlook to the rating they give – stable, positive or negative – which indicates the likely trend of the rating over the two to three years ahead.

Short- and medium-term ratings may be modified by a + or − or a numerical modifier, which indicates the position of the company within its generic rating category. The watchlist alerts investors that an event such as an acquisition, disposal or merger, once it has been weighed into the analysis, is likely to lead to a change in the rating. A company on the watchlist is likely to be upgraded when the expected outcome is positive, downgraded when the expected outcome is negative and, when the agency is unable to determine the outcome, it indicates an unknown change.

Short-term ratings are not independent of long-term ratings, as seen in the following diagram.

Source: Standard & Poor’s

Ratings between AAA and BBB− are referred to as investment grade, and those between BB+ and D as speculative grade (or non-investment grade). The distinction between these two types of risk is important to investors, especially institutional investors, who often are not permitted to buy the risky speculative grade bonds!

From the sample of international issuers rated by Standard & Poor’s over 15 years, 0.9% of issuers rated AAA failed to pay an instalment on a loan, while 29% of issuers rated B defaulted.

Source: Standard & Poor’s 2017

Bonds rated between BBB and BB (potentially with a + or a −) are called crossover bonds. This is an intermediate category that links the investment grade and non-investment grade categories.

In Europe, rating agencies generally rate companies at their request, which enables them to access privileged information (medium-term plans, contacts with management). Rating agencies very rarely rate companies without management cooperation. When they do, the accuracy of the rating depends on the quality of the information about the company available on the market. If the company does not require a public rating immediately (or if it does not like the rating allocated!), it may request that it be kept confidential, and it is then referred to as a shadow rating. The cost for a firm to get a first rating is quite high (over €500 000 on average, to which should be added an annual cost of over €100 000).

The rating process differs from the scoring process as it is not only a quantitative analysis. The agency will also take into account:

- the positioning of the company in its sector;

- the analysis of the financial data;

- the current capital structure but also the financing strategy (which is perceived mainly through meetings with management).