Chapter 45

Mergers and demergers

When the financial manager celebrates a wedding (or a divorce!)

At first glance, this chapter might seem to repeat the previous ones in that selling a company almost always leads to linking it up with another. In everyday language we often talk of the merger of two companies, when in reality one company typically takes control of the other, using the methods described in Chapter 44. In fact, all that we have previously said about synergies and company valuations will be used in this chapter. The only fundamental difference we introduce here is that 100% of the seller’s consideration will be in shares of the acquiring company and not in cash.

In addition, because markets nowadays prefer “pure-play” companies, demergers have come back into fashion. We will take a look at them in Section 45.3.

Section 45.1 All-share deals

In this section, we will examine the general case of two separate companies that decide to pool their operations and redistribute roles. Before the business combination can be consummated, questions of valuation and power-sharing among the shareholders of the new entity must be resolved. Financially, the essential distinguishing feature among mergers and acquisitions is the nature of the consideration paid: 100% cash, a combination of cash and shares or 100% shares. Our discussion will focus on the last of these forms. Finally, we will not address the case of a company that merges with an already wholly owned subsidiary, which raises only accounting, tax and legal issues and no financial issues.

1. The different techniques

(a) Legal merger

A legal merger is a transaction by which two or more companies combine to form a single legal entity. In most cases, one company absorbs the other. The shareholders of the acquired company become shareholders of the acquiring company and the acquired company ceases to exist as a separate legal entity.

From legal and tax points of view, this type of business combination is treated as a contribution of assets and liabilities, paid in new shares issued to the ex-shareholders of the acquired company.

(b) Contribution of shares

Consider the shareholders of Companies A and B. Shareholders of Company B, be they individuals or legal entities, can enter into a deal with Company A wherein they exchange their shares of B for shares of A. In this case, Companies A and B continue to exist, with B becoming a subsidiary of A and the shareholders of B becoming shareholders of A.

Financially and economically, the transaction is very close to the sale of all or part of Company B funded by an equivalent issue of new Company A shares, reserved for the shareholders of Company B.

For listed companies, the most common approach for achieving this result is a share exchange offer, as described in Chapter 44.

(c) Asset contribution

In a contribution (or transfer) of assets, Company B contributes a portion (or sometimes all) of its assets (and liabilities) to Company A in return for shares issued by Company A.

In a legal merger, the shareholders of Company B receive shares of Company A. In a transfer of assets, however, Company B, not the shareholders thereof, receives the shares of Company A. The position of Company B shareholders is therefore substantially different, depending on whether the transaction is a legal merger or a simple transfer of assets. In the transfer of assets, Company B remains and becomes a shareholder of Company A. Shareholders of B do not become direct shareholders of A. In the legal merger, shareholders of B become direct shareholders of A.

If Company B contributes all of its assets to A, B becomes a holding company and, depending on the amount of the assets it has contributed, can take control of A. This procedure is often used in corporate restructurings to transfer certain activities to subsidiaries.

Economically, there is no difference between these transactions. The group created by bringing together A and B is economically identical regardless of how the business combination is effected.

As an example of asset contribution, you can have a look at the EssilorLuxottica transaction in 2017. Delfin, controlled by Leonardo Del Vecchio, contributed its 61% stake in Luxottica to Essilor in exchange for 31% of the new EssilorLuxottica.

2. Analysis of the different techniques

For simplicity’s sake, we will assume that the shares of both companies are fairly priced and that the merger does not create any industrial or commercial synergies. Consequently, there is no value creation as a result of the merger.

(a) From the point of view of the company

Companies A and B have the following characteristics:

| (€m) | Enterprise value | Value of shareholders’ equity agreed in the merger |

| Company A | 900 | 450 |

| Company B | 500 | 375 |

Depending on the method used, the post-transaction situation is as follows:

| (€m) | A acquires B shares for cash1 | A merges with B | A issues new shares in exchange for B shares and B becomes a 100% subsidiary of A | A issues new shares in exchange for assets and liabilities of B |

| Value of A’s new capital employed (now A + B) | 1400 | 1400 | 1400 | 1400 |

| Value of A’s shareholders’ equity | 450 | 825 | 825 | 825 |

| Percentage of A held by A shareholders | 100% | 54.5% | 54.5% | 54.5% |

| Percentage of A held by B shareholders | — | 45.5% | 45.5% | 45.5%2 |

Enterprise value and consolidated operating income are the same in each scenario. Economically, each transaction represents the same business combination of Companies A and B.

Financially, however, the situation is very different, even putting aside accounting issues. If A pays for the acquisition in shares, then the shareholders’ equity of A is increased by the shareholders’ equity of B. If A purchases B for cash, then the value of A’s shareholders’ equity does not increase.

It can be noted that when the target is a listed company, a 100% successful share exchange offer is financially equivalent to a legal merger.

We reiterate that our reasoning here is strictly arithmetic and we are not taking into account any impact the transaction may have on the value of the two companies. If the two companies were already correctly priced before the transaction and there are no synergies, their value will remain the same. If not, there will be a change in value. The financial mechanics (sale, share exchange, etc.) have no impact on the economics of a business combination.

That said, there is one important financial difference: an acquisition paid for in cash does not increase a group’s financial clout (i.e. future investment capacity), but an all-share transaction creates a group with financial means, which tends to be the sum of that of the two constituent companies.

In terms of value creation, our rules still hold, unless there are synergies or market inefficiencies.

(b) From the point of view of shareholders

A cash acquisition changes the portfolio of the acquired company’s shareholders, because they now hold cash in place of the shares they previously held.

Conversely, it does not change the portfolio of the acquiring company’s shareholders, nor their stake in the company.

An all-share transaction is symmetrical for the shareholders of A and B. No one receives any cash. When the dust settles, they all hold claims on a new company born out of the two previous companies. Note that their claims on the merged company would have been exactly the same if B had absorbed A. In fact, who absorbs whom is not so important; it is the percentage ownership the shareholders end up with that is important. Moreover, it is common for one company to take control of another by letting itself be “absorbed” by its “target”.

Merger synergies are not shared in the same way. In a cash acquisition, selling shareholders pocket a portion of the value of synergies immediately (depending on the outcome of the negotiation). The selling shareholders do not bear any risk of implementation of the synergies. In an all-share transaction, however, the value creation (or destruction) of combining the two businesses will be shared according to the relative values negotiated by the two sets of shareholders.

For the shareholders of Company B, a contribution of shares, with B remaining a subsidiary of A, has the same effect as a legal merger of the two companies. An asset contribution of Company B to Company A is also very similar to a legal merger. The only difference is that, in an asset contribution, the claim of Company B’s ex-shareholders on Company A is via Company B, which becomes a holding company of Company A.

3. Pros and cons of paying in shares

In contrast to a cash acquisition, there is no cash outflow in an all-share deal, be it an exchange of shares, an asset contribution in return for shares or a demerger with a distribution of shares in a new company. The transaction does not generate any cash that can be used by shareholders of the acquired company to pay capital gains taxes. For this reason, it is important for these transactions to be treated as “tax-free”.

What is the advantage of paying in shares? Sometimes company managers want to change the ownership structure of the company so as to dilute an unwelcome shareholder’s stake, constitute a group of core shareholders or increase their power by increasing the company’s size or prestige. More importantly, paying in shares enables the company to skirt the question of financing and merge even with very large companies. Some critics say that companies paying in shares are paying for their acquisitions with “funny money”; we think that depends on the post-merger ownership structure and share liquidity. Most importantly, it depends on the ability of the merged company to harness anticipated synergies and create value. In Chapter 44, we provide a table setting out the pros and cons of payment in shares vs. cash.

Section 45.2 The mechanics of all-share transactions

1. Exchange ratio and relative value ratio

To carry out a merger, you need to determine the exchange ratio, i.e. the ratio of the number of shares of one company to be issued for each share of the other company received.

When both companies have similar activities, the ratios of their earnings per share, cash flow per share, dividend per share, book equity per share, shares prices (when they are listed) are computed. Some even compute ratios of sales per share, EBITDA per share, EBIT per share. This is relevant only if the capital structures of both companies are similar.

When companies have dissimilar activities, like a diversified group and a one-product group or a holding company and an industrial group, then a full valuation of the two companies to be merged is generally performed according to the methods described in Chapter 31. Such a valuation is usually done on a standalone basis, with synergies valued separately. As far as possible, the same valuation methods should be used to value each company.

Let us take another look at Companies A and B, with the following key figures:

| Earnings per share | Share price | Dividend per share | |

| A (acquirer) | €3.33 | €100 | €1 |

| B (acquiree) | €9.33 | €176 | €2.3 |

| Exchange ratio | 2.80 | 1.76 | 2.30 |

The final exchange ratio agreed upon may be 2.

Let’s now move from the per-share level, which has allowed us to compute the exchange ratio, to the level of shareholders’ equity value agreed in the merger. The ratio of shareholders’ equity value of Company A to shareholders’ equity value of Company B is called the relative value. A relative value of 0.8333 (B’s value being equal to 0.833 A’s value) gives to the current B shareholders a stake of 0.833/(0.833 + 1) = 45.5% in the merged entity. Hence, A shareholders will get a stake of 1/(0.8333 + 1) = 54.5%. 0.833 corresponds to the ratio of the values of shareholders’ equity agreed in the merger, €450m and €375m, respectively.

If the relative value ratio agreed in the merger had been 0.9, A shareholders would have obtained a stake of 52.6% in the merger entity and B shareholders a stake of 47.4%.

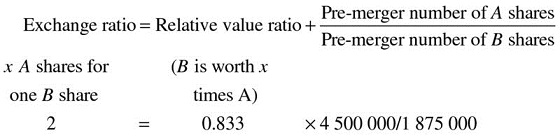

Once relative values are determined, calculating the exchange ratio is a simple matter:

The 1 875 000 B shares will be exchanged for 1 875 000 × 2 = 3 750 000 new A shares issued by A to remunerate B shareholders. After the merger the outstanding share capital of A will be made up of 4 500 000 + 3 750 000 = 8 250 000 shares.

2. Dilution or accretion criteria

To help refine our analysis, let us suppose that Companies A and B have the following key financial elements:

| (€m) | Sales | Net income | Book equity | Value of shareholders’ equity3 |

| A | 1500 | 15 | 250 | 450 |

| B | 2500 | 17.5 | 225 | 330 |

Putting aside for one moment potential industrial and commercial synergies, the financial elements of the new Company A + B resulting from the merger with B are as follows:

| (€m) | Sales | Net income | Book equity | Value of shareholders’ equity |

| Group A + B | 4000 | 32.5 | 475 | 780 |

In theory, the value of the new entity’s shareholders’ equity should be the sum of the value of the shareholders’ equity of A and B. In practice, it is higher or lower than this amount, depending on how advantageous investors believe the merger is.

Using the agreed relative value ratio of 0.833 (B value is 0.833 the value of A), our performance measures for the new group are as follows:

| (€m) | Group net income | Group book equity | Theoretical value of group shareholders’ equity |

The ex-shareholders of A have a claim on: vs. before the transaction: |

17.7 15 |

259 250 |

425 450 |

| The ex-shareholders of B have a claim on: vs. before the transaction: |

14.8 17.5 |

216 225 |

355 330 |

| TOTAL Before transaction: After transaction: |

32.5 32.5 |

475 475 |

780 780 |

Turning our attention now to the earnings per share of Companies A and B, we observe the following:

| Value of shareholders’ equity (€m) | Net income (€m) | P/E5 | Number of shares (million) | Earnings per share (€) | |

| Company A | 450 | 15 | 30 | 4.5 | 3.33 |

| Company B | 330 | 17.5 | 18.9 | 1.875 | 9.33 |

On the basis of the relative value ratio agreed in the merger of 0.833 (375/450), the earnings per share of the new group A now stands at (15 + 17.5)/(4.5 + 3.75), or €3.94 per share. EPS has risen from 3.33 to 3.94, representing an increase of slightly less than 20%. The reason is that the portion of earnings deriving from ex-Company B is purchased with shares valued at A’s P/E multiple of 30 (450/15), whereas B is valued at a P/E multiple of 21 (375/17.5). Company A has issued a number of shares that are relatively low compared with the additional net income that B has contributed to A’s initial net income.

The reasoning is similar for other performance metrics, such as cash flow per share.

3. Synergies

As an all-share merger consists conceptually of a purchase followed by a reserved capital increase, the sharing of synergies is a subject of negotiation just as it is in the case of a cash purchase.

In our example, let us suppose that synergies between A and B will increase the after-tax income of the merged group by €10m from the first year onwards.

The big unknown is the credit and the value investors will ascribe to these synergies:

- €300m – i.e. a valuation based on A’s P/E multiple of 30;

- €189m – i.e. a valuation based on B’s P/E multiple of 18.9;

- €240m – i.e. a valuation based on a P/E multiple of 24, the average of the P/Es of A and B (780/32.5);

- some other value.

Two factors lead us to believe that investors will attribute a value that is lower than these estimates:

- The amount of synergies announced at the time of the merger is only an estimate and the announcers have an interest in maximising it to induce shareholders to approve the transaction. In practice, making a merger or an acquisition work is a managerial challenge. You have to motivate employees who may previously have been competitors to work together, create a new corporate culture, avoid losing customers who want to maintain a wide variety of suppliers, etc. Experience has shown that:

- more than half of all mergers fail on this score;

- actual synergies are slower in coming;

- the amount of synergies is lower than originally announced.

- Sooner or later, the company will not be the only one in the industry to merge. Because mergers and acquisitions tend to come in waves, rival companies will be tempted to merge for the same reasons: to unlock synergies and remain competitive. As competition also consolidates, all market participants will be able to lower prices or refrain from raising them, to the joy of the consumer. As a result, the group that first benefited from merger synergies will be forced to give back some of its gains to its customers, employees and suppliers.

A study of the world’s largest mergers and acquisitions shows that the P/E multiple at which the market values synergies when they are announced is well below that of both the acquiring company and the target.

Based on this information, let’s assume that the investors in our example value the €10m p.a. in synergies at a P/E of 12, or €120m. The value of shareholders’ equity of the new group is therefore:

Value is created in the amount of 900 − 780 = €120m. This is not financial value creation, but the result of the merger itself, which leads to cost savings and/or revenue enhancements, i.e. synergies. The €120m synergy pie will be shared between the shareholders of A and B.

At the extreme, the shareholders of A might value B at €450m. In other words, they might attribute the full present value of the synergies to the shareholders of B. The relative value ratio would then be at its maximum, 1.6 Note that in setting the relative value ratio at 0.833, they had already offered the ex-shareholders of B 66%3 of the value of the synergies!

The relative value ratios of 0.579 (330/(450 + 120)) and 1 constitute the upper and lower financial boundaries of the negotiable range. If they agree on 0.579, the shareholders of A will have kept all of the value of the synergies for themselves. Conversely, at 1, all of the synergies accrue to the shareholders of B.

The relative value choice determines the relative ownership stake of the two groups of shareholders, A’s and B’s, in the post-merger group, which ranges from 36.7%/63.3% to 50%/50%, and consequently the value of their respective stakes.

Determining the value of potential synergies is a crucial negotiating stage. It determines the maximum merger premium that Company A will be willing to pay to the shareholders of Company B:

- large enough to encourage shareholders of B to approve the merger;

- small enough to still be value-creating for A’s shareholders.

4. The “bootstrap game”

Until now, we have assumed that the market capitalisation of the new group will remain equal to the sum of the two initial market capitalisations. In practice, a merger often causes an adjustment in the P/E, called a rerating (or a derating!). As a result, significant transfers of value occur to and between the groups of shareholders. These value transfers often offset a sacrifice with respect to the post-merger ownership stake or a post-merger performance metric.

If we assume that the new Group A continues to enjoy a P/E ratio of 30 (ignoring synergies), as did the pre-merger Company A, its market capitalisation will be €975m. The ex-shareholders of A, who appeared to give up some relative value with regard to the post-merger market cap metric, see the value of their share of the new group rise to €531m,4 whereas they previously owned 100% of a company that was worth only €450m. As for the ex-shareholders of B, they now hold 45.5% of the new group, a stake worth €444m, vs. 100% of a company previously valued at only €330m.

Whereas it seemed A’s shareholders came out losing, in fact it’s a win–win situation. The transaction is a money machine! The limits of this model are clear, however. A’s pre-merger P/E of 30 was the P/E ratio of a growth company. Group A will maintain its level of growth after the merger only if it can light a fire under B and convince investors that the new group also merits a P/E ratio of 30.

This model works only if Company A keeps growing through acquisition, “kissing” larger and larger “sleeping beauties” and bringing them back to life. If not, the P/E ratio of the new group will simply correspond to the weighted average of the P/E ratios of the merged companies.

You have probably noticed by now that it is advantageous to have a high share price, and hence a high P/E ratio. They allow you to issue highly valued paper to carry out acquisitions at relatively low cost, all the while posting automatic increases in earnings per share. You undoubtedly also know how to recognise an accelerating treadmill when you see one.

The potential immediate rerating after the merger does not guarantee creation of shareholder value. In the long run, only the new group’s economic performance will enable it to maintain its high P/E multiple.

5. Which way should the merger go?

Is A going to absorb B or the reverse? Several factors have to be taken into account.

Whether the company is listed or not is a factor, since in a merger between a listed and an unlisted company, it is likely that the listed company will take over the unlisted one in order to simplify administrative procedures and to avoid an exchange of shares for the hundreds, thousands or even hundreds of thousands of shareholders of the listed company.

There are, of course, legal considerations when agreements signed by the acquired company contain a change-of-control clause, for example in the concessions sector or for loan agreements, with some loans falling due immediately.

There are also psychological reasons why sometimes it makes more sense to continue trading under the name or structure of an entity which has been in existence for a very long time and which has great sentimental value for management and shareholders. In such cases, it is the oldest structure that becomes the acquiring company (although the name of the acquiring company could also just be changed).

There are also some managers who believe that they will be in a better position within the new structure if their company is the acquiring company rather than the acquired company. There are others who wish to make a symbolic statement about where the power lies.

Then there are those who are obsessed with EPS, who are keen for the acquiring company to be the one with the highest P/E ratio so the merger will be accretive in terms of EPS. Our readers know how cautious we are when it comes to EPS.5

In some countries, the tax issue is the main factor in deciding which way the merger should go. The acquired company loses all of its tax-loss carryforwards, while the acquiring company is allowed to hold onto its own. Elsewhere, it is possible for the company resulting from the merger of two companies to hold onto the tax-loss carryforwards of the company that is acquired, provided that the merger is not being carried out solely for tax reasons. This reduces the importance of the tax issue in deciding who should take over whom.

6. Cross-border mergers in Europe

Cross-border mergers between companies (joint-stock companies, limited liability companies, European companies, simplified joint-stock companies) in EU member states are made possible by a European Directive which does not, however, cover partnerships.

Rules that have been harmonised at a European level apply to the cross-border merger procedure itself, which makes provision for prior checks to ensure that the merger is compliant, carried out by the registrar of the court that has jurisdiction over each company, and checks that it is legal by a notary or court registrar. Subsequently, local law applies for each of the parties involved in as far as they are specifically concerned. So, for the acquisition of a French company, French law will apply with regard to the consultation and rights of minority shareholders, the right of creditors who are not bondholders to raise objections and the right of bondholders.

Intra-European combinations are made much easier if the companies are set up as or adopt the status of European companies, as in the case of Airbus, LVMH, Allianz, Porsche and others.

Section 45.3 Demergers and split-offs

Demergers are not uncommon in countries where their tax treatment is not punitive.

1. Principles

The principle of a demerger is simple. A group with several divisions, in most cases two, decides to separate them into distinct companies. The shares of the newly created companies are distributed to the shareholders in exchange for shares of the parent group. The shareholders, who are the same as the shareholders of the original group, now own shares in two or more companies and can buy or sell them as they see fit.

There are two basic types of transactions, depending on whether, once approved, the transaction applies to all shareholders or gives shareholders the option of participating.

- A demerger is a separation of the activities of a group: the original shareholders become the shareholders of the separated companies. The transaction can be carried out by distributing the shares of a subsidiary in the form of a dividend (a spin-off), or by dissolving the parent company and distributing the shares of the ex-subsidiaries to the shareholders (a split-up). Immediately after the transaction, the shareholders of the demerged companies are the same, but ownership evolves very quickly thereafter.

- In a split-off, shareholders have the option to exchange their shares in the parent company for shares in a subsidiary. To avoid unnecessary holdings of treasury shares, the shares tendered are cancelled. A split-off is a share repurchase paid for with shares in a subsidiary rather than in cash. If all shareholders tender their shares, the split-off is identical to a demerger. If the offer is relatively unsuccessful, the parent company remains a shareholder of the subsidiary.

2. Why demerge?

Broadly speaking, studies on demergers have shown that the shares of the separated companies outperform the market, both in the short and long term.

In the context of the efficient markets hypothesis and agency theory, demergers are an answer to conglomerate discounts (see Chapter 41) or groups that are too diversified. In this sense, a demerger creates value because it solves the following problems:

- Allocation of capital within a conglomerate is suboptimal, benefiting divisions in difficulty and penalising healthy ones, making it harder for the latter to grow.

- The market values primary businesses correctly but undervalues secondary businesses. A demerger can also help a group to dispose of an asset that is hard to sell (South 32 for BHP Billiton).

- The market has trouble understanding conglomerates, a problem made worse by the fact that virtually all financial analysts are specialised by industry. With the number of listed companies constantly growing and investment possibilities therefore expanding, investors prefer simplicity. In addition, large conglomerates communicate less about smaller divisions, thus increasing the information asymmetry.

- Lack of motivation of managers of non-core divisions.

- Small base of investors interested by all the businesses of the group.

- The conglomerate has operating costs that add to the costs of the operating units without creating value.

Demergers expose the newly created companies to potential takeovers. Prior to the demerger, the company might have been too big or too diverse. Potential acquirers might not have been interested in all of its businesses, and the process of acquiring the entire company and then selling off the unwanted businesses is cumbersome and risky. A demerger creates smaller, pure-play companies, which are more attractive in the takeover market. Empirically, it has been shown that demerged subsidiaries do not always outperform. This is the case when the parent company has completely divested its interest in the new company or has itself become subject to a takeover bid.

Lastly, lenders are not great fans of demergers. By reducing the diversity of activities and consequently potentially increasing the volatility of cash flows, they increase the risk for lenders. At one extreme, the value of their debt decreases if the transaction is structured in such a way that one of the new companies carries all the debt, while the other is financed by equity capital only.

In practice, however, debtholders are rarely spoiled that way. Loan agreements and bond indentures generally stipulate that, in the event of a demerger, the loan or the bonds become immediately due and payable.

Consequently they are in a position to negotiate demerger terms that are not unfavourable to them. This explains why empirical studies have shown that, on average, demergers lead to no transfer of value from creditors to shareholders.

Because of their complexity and the detailed preparation they require (over at least six months), demergers are less frequent than mergers. Examples of demergers include News Corp (newspapers) and 21st Century Fox (TV and movies), Accor (hotels) and Edenred (prepaid corporate services) and for split-offs, Pfizer/Zoetis (animal health), Procter & Gamble and Folger (coffee), Sequana (paper) and SGS (certification).

Demerging is not a panacea. If one of the demerged businesses is too small, its shares will suffer a deep liquidity discount. In emerging countries where access to financial markets is tougher than in mature economies, the diversification of groups seems to be a success factor (Tata or Reliance in India, Argos in Columbia, Fosun in China, etc.). There, the word demerger is unknown … for the moment.

If we wanted to be cynical, we might say that demergers represent the triumph of sloth (investors and analysts do not take the time to understand complex groups) and selfishness (managers want to finance only the high-performance businesses).