Chapter 11

Working capital and capital expenditures

Building the future

As we saw in the standard financial analysis, all value creation requires investment. In finance, investment means creating either new fixed assets or working capital. The latter, often high in Continental Europe, deserves some explanation.

Section 11.1 The nature of working capital

Every analyst intuitively tries to establish a percentage relationship between a company’s working capital and one or more of the measures of the volume of its business activities. In most cases, the chosen measure is annual turnover or sales.

The ratio:

reflects the fact that the operating cycle generates an operating working capital that includes:

- capital “frozen” in the form of inventories, representing procurement and production costs that have not yet resulted in the sale of the company’s products;

- funds “frozen” in customer receivables, representing sales that customers have not yet paid for;

- accounts payable that the company owes to suppliers.

The balance of these three items represents the net amount of money tied up in the operating cycle of the company. In other words, if the working capital turnover ratio is 25% (which is high), this means that 25% of the company’s annual sales volume is “frozen” in inventories and customer receivables not financed by supplier credit. This also means that, at any moment, the company needs to have on hand funds equal to a quarter of its annual sales to pay suppliers and employee salaries for materials and work performed on products or services that have not yet been manufactured, sold or paid for by customers.

Since the beginning of this century, the working capital of large listed European groups has had a tendency to shrink, as illustrated in the following table:

WORKING CAPITAL EXPRESSED AS A % OF SALES (EUROPEAN LISTED GROUPS)

| Sector | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2016e | 2017e |

| Aerospace & Defence | −1% | −16% | −21% | −16% | −18% | −17% |

| Automotive | 4% | 2% | 2% | −2% | −2% | −1% |

| Building Materials | 15% | 15% | 9% | 8% | 8% | 8% |

| Capital Goods | 5% | 11% | 7% | 9% | 9% | 9% |

| Consumer Goods | 25% | 19% | 16% | 17% | 17% | 17% |

| Food Retail | −5% | −6% | −8% | −8% | −8% | −8% |

| IT Services | 19% | −3% | 2% | −2% | −1% | 0% |

| Luxury Goods | 22% | 15% | 17% | 24% | 23% | 23% |

| Media | −9% | −17% | −16% | −11% | −10% | −10% |

| Mining | 10% | 11% | 11% | 8% | 9% | 9% |

| Oil & Gas | 1% | 4% | 4% | 5% | 7% | 7% |

| Pharmaceuticals | 22% | 12% | 12% | 9% | 10% | 10% |

| Steel | 26% | 19% | 23% | 16% | 17% | 17% |

| Telecom Operators | −9% | −17% | −12% | −7% | −6% | −6% |

| Utilities | 4% | −6% | 2% | 2% | 3% | 3% |

Source: Exane BNP Paribas

As we will see in Section 11.2, working capital is often expressed as a number of days of sales. This figure is derived by multiplying a percentage ratio by 365. In our example, a ratio of 25% indicates that working capital totals around 90 days of the company’s sales.

1. Steady business, permanent working capital

Calculated from the balance sheet, a company’s working capital is the balance of the accounts directly related to the operating cycle. According to traditional financial theory, these amounts are very liquid; that is, they will either be collected or paid within a very short period of time. But in fact, although it is liquid, working capital also reflects a permanent requirement.

No matter when the books are closed, the balance sheet always shows working capital, although the amount changes depending on the statement date. The only exceptions are the rare companies whose operating cycle actually generates cash rather than absorbs it.

Working capital is liquid in the sense that every element of it disappears in the ordinary course of business. Raw materials and inventories are consumed in the manufacturing process. Work in progress is gradually transformed into finished products. Finished products are (usually) sold. Receivables are (ordinarily) collected and become cash, bank balances, etc. Similarly, debts to suppliers become outflows of cash when they are paid.

As a result, if the production cycle is less than a year (which is usually the case), all of the components of working capital at the statement date will disappear in the course of the following year. But at the next statement date, other operating assets will have taken their place. This is why we view working capital as a permanent requirement.

Even if each component of working capital has a relatively short lifetime, the operating cycles are such that the contents of each are replaced by new contents. As a result, if the level of business activity is held constant, the various working capital accounts remain at a constant level.

All in all, at any given point in time, a company’s working capital is indeed liquid. It represents the difference between certain current assets and certain current liabilities. But thinking in terms of “permanent working capital” introduces a radically different concept. It suggests that if business is stable, current (liquid) operating assets and current operating liabilities will be renewed and new funds will be tied up, constituting a permanent capital requirement as surely as fixed assets are a permanent capital requirement.

2. Seasonal business activity, partly seasonal requirement

When a business is seasonal, purchases, production and sales do not take place evenly throughout the year. As a result, working capital also varies during the course of the year, expanding then contracting.

The working capital of a seasonal business never falls to zero. Whether the company sells canned vegetables or raincoats, a minimum level of inventories is always needed to carry the company over to the next production cycle.

In our experience, companies in seasonal businesses often pay too much attention to the seasonal aspect of their working capital and ignore the fact that a significant part of it is permanent. As some costs are fixed, so are some parts of the working capital.

We have observed that in some very seasonal businesses, such as toys, the peak working capital is only twice the minimum. This means that half of the working capital is permanent, the other half is seasonal.

3. Conclusion: permanent working capital and the company’s ongoing needs

Approximately 30% of all companies close their books at a date other than 31 December. They choose these dates because that is when the working capital requirement shown on their balance sheets is lowest. This is pure window dressing. Bordeaux vineyards close on 30 September, Caribbean car rental companies on 30 April.

A company in trouble uses trade credit to the maximum possible extent. In this case, you must restate working capital by eliminating trade credit that is in excess of normal levels. Similarly, if inventory is unusually high at the end of the year because the company speculated that raw material prices would rise, then the excess over normal levels should be eliminated in the calculation of permanent working capital. Lastly, to avoid giving the impression that the company is too cash-rich, some companies make an extra effort to pay their suppliers before the end of the year. This is more akin to investing cash balances than to managing working capital.

Although the working capital on the balance sheet at year end can usually not be used as an indicator of the company’s permanent requirement, its year-to-year change can still be informative. Calculated at the same date every year, there should be no seasonal impact. Analysing how the requirement has changed from year end to year end can shed light on whether the company’s operations are improving or deteriorating.

You are therefore faced with a choice:

- if the company publishes quarterly financial statements, you can take the permanent working capital to be the lowest of the quarterly balances and the average working capital to be the average of the figures for each of the four quarters;

- if the company publishes only year-end statements, you must reason in terms of year-to-year trends and comparisons with competitors.1

Section 11.2 Working capital turnover ratios

As financial analysis consists of uncovering hidden realities, let’s simulate reality to help us understand the analytical tools.

Working capital accounts are composed of uncollected sales, unsold production and unpaid-for purchases, in other words, the business activities that took place during the days preceding the statement date. Specifically:

- if customers pay in 15 days, receivables represent the last 15 days of sales;

- if the company pays suppliers in 30 days, accounts payable represent the last 30 days of purchases;

- if the company stores raw materials for three weeks before consuming them in production, the inventory of raw materials represents the last three weeks of purchases.

These are the principles. Naturally, the reality is more complex, because:

- payment periods can change;

- business is often seasonal, so the year-end balance sheet may not be a real picture of the company;

- payment terms are not the same for all suppliers or all customers;

- the manufacturing process is not the same for all products.

Nevertheless, working capital turnover ratios calculated on the basis of accounting balances represent an attempt to see the reality behind the figures. But let’s not delude ourselves. At the very best the external analyst will arrive at an approximate estimation of the company’s payment periods rather than its actual payment periods. Nevertheless, the development of these ratios over several years will provide a reliable trend.

1. The menu of ratios

(a) Days’ sales outstanding (DSO)

The days’ sales outstanding (or days/receivables) ratio measures the average payment terms the company grants its customers (or the average actual payment period). It is calculated by dividing the receivables balance by the company’s average daily sales, as follows:

As the receivables on the balance sheet are shown inclusive of VAT, for consistency, sales must be shown on the same basis. But the sales shown on the profit and loss statement are exclusive of VAT. You must therefore increase them by the applicable VAT rate for the products the company sells or by an average rate if it sells products taxed at different rates.

Receivables are calculated as follows:

Customer receivables and related accounts + Outstanding bills discounted (if not already included in receivables) − Advances and deposits on orders being processed = Total receivables

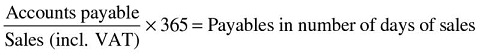

(b) Days’ payables outstanding (DPO)

The days/payables ratio measures the average payment terms granted to the company by its suppliers (or the average actual payment period). It is calculated by dividing accounts payable by average daily purchases, as follows:

Accounts payable are calculated as follows:

Accounts payable and related accounts + Advances and deposits paid on orders = Total accounts payable

To ensure consistency, purchases are valued inclusive of VAT. They are calculated as follows:

| Purchase of goods held for resale (incl. VAT) | |

| + | Purchase of raw materials (incl. VAT) |

| + | Other external costs (incl. VAT) |

| = | Total purchases |

The amounts shown on the profit and loss statement must be increased by the appropriate VAT rate.

When the figure for annual purchases is not available (mainly when the income statement is published in the by-function format), the days’ payables ratio is approximated as:

(c) Days’ inventory outstanding (DIO)

The significance of the inventory turnover ratios depends on the quality of the available accounting information. If it is detailed enough, you can calculate true turnover ratios. If not, you will have to settle for approximations that compare dissimilar data.

You can start by calculating an overall turnover ratio, not meaningful in an absolute sense, but useful in analysing trends:

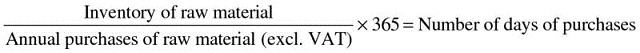

Depending on the available accounting information, you can also calculate the turnover of each component of inventory, in particular raw materials and goods held for resale, and distil the following turnover ratios:

-

Days of raw material, reflecting the number of days of purchases the inventory represents or, viewed the other way round, the number of days necessary for raw materials on the balance sheet to be consumed:

-

Days of goods held for resale, reflecting the period between the time the company purchases goods and the time it resells them:

-

Days of finished goods inventory, reflecting the time it takes the company to sell the products it manufactures, and calculated with respect to cost of goods sold:

-

If cost of goods sold is unavailable, it is calculated with respect to the sales price:

Days of work in progress, reflecting the time required for work in progress and semi-finished goods to be completed – in other words, the length of the production cycle:

For companies that present their profit and loss statement by nature, this last ratio can be calculated only from internal sources as cost of goods sold does not appear as such on the P&L. The calculation is therefore easier for companies that use the by-function presentation for their profit and loss statement.

2. The limits of ratio analysis

Remember that, in calculating the foregoing ratios, you must follow two rules:

- make sure the basis of comparison is the same: sales price or production cost, inclusive or exclusive of VAT;

- compare outstandings in the balance sheet with their corresponding cash flows.

Turnover ratios have their limitations:

- they can be completely misleading if the business of the company is seasonal. In this case, the calculated figures will be irrelevant. To take an extreme example, imagine a company that makes all of its sales in a single month. If it grants payment terms of one month, its number of days’ receivables at the end of that month will be 365;

- they provide no breakdown – unless more detailed information is available – of the turnover of the components of each asset (or liability) item related to the operating cycle. For example, receivables might include receivables from private-sector customers, international customers and government agencies. These three categories can have very different collection periods (government agencies, for instance, are known to pay late).

You must ask yourself what degree of precision you want to achieve in your analysis of the company. If a general idea is enough, you might be satisfied with average ratios, as calculated above, after verifying that:

- the business is not too seasonal;

- if it is seasonal, then the available data refer to the same point in time during the year. If this is the case, we advise you to express the ratios in terms of a percentage (receivables/sales), which does not imply a direct link with actual payment conditions.

If you need a more detailed analysis, you will have to look at the actual business volumes in the period just prior to the statement date. In this case, the daily sales figure will not be the annual sales divided by 365, but the last quarter’s sales divided by 90, the last two months divided by 60, etc.

If you must perform an in-depth audit of outstandings in the balance sheet, averages are not enough. You must compare outstandings with the transactions that gave rise to them.

Section 11.3 Reading between the lines of working capital

Evaluating working capital is an important part of an analyst’s job in Continental Europe, because intercompany financing plays a prominent role in the economy. In Anglo-Saxon countries this analysis is less important, because working capital is much lower, either because it is usual practice to offer a discount for prompt payments (USA) or because for decades companies have been used to paying promptly.

1. Growth of the company

In principle, the ratio of working capital to annual sales should remain stable.

If the permanent requirement equals 25% of annual sales and sales grow from €100m to €140m, the working capital requirement should grow by €10m (€40m × 25%).

Growth in business volume causes an increase in working capital. This increase appears, either implicitly or explicitly, in the cash flow statement.

We might be tempted to think that working capital does not grow as fast as sales because certain items, such as minimum inventory levels, are not necessarily proportional to the level of business volume. Experience shows, however, that growth very often causes a sharp, sometimes poorly controlled, increase in working capital at least proportional to the growth in the company’s sales volume.

In fact, a growing company is often confronted with working capital that grows faster than sales, for various reasons:

- management sometimes neglects to manage working capital rigorously, concentrating instead on strategy and on increasing sales;

- management often tends to integrate vertically, both upstream and downstream. Consequently, structural changes to working capital are introduced as it starts growing much more rapidly than sales, as we will explain later on.

When a company is growing, the increase in working capital constitutes a real use of funds, just as surely as capital expenditures do. For this reason, increases in working capital must be analysed and projected with equal care.

Efficient companies are characterised by controlled growth in working capital. Indeed, successful expansion often depends on the following two conditions:

- ensuring that the growth in working capital tracks the growth in sales rather than zooming ahead of it;

- creating a corporate culture that strives to contain working capital. If working capital grows unchecked, sooner or later it will lead to serious financial difficulties and compromise the company’s independence.

Today, companies faced with slower growth in business manage working capital strictly through just-in-time inventory management, greater use of outsourcing, reorganisation of internal payment circuits, financial incentives for salespeople linked to customers’ payments, etc. (as we will see in Chapter 48).

2. Recession

By analysing the working capital of a company facing a sudden drop in its sales, we can see that it reacts in stages.

Initially, the company does not adjust its production levels. Instead, it tries other ways to shore up sales. The recession also leads to difficulty in controlling accounts receivable, because customers start having financial difficulties and stretch out their payments over time. The company’s cash situation deteriorates, and it has trouble honouring its commercial obligations, so it secures more favourable payment terms from its suppliers. At the end of this first phase, working capital – the balance between the various items affected by divergent forces – stabilises at a higher level. This situation was experienced in particular by car manufacturers in late 2008.

In the second phase, the company begins to adopt measures to adjust its operating cycle to its new level of sales. It cuts back on production, trims raw material inventories and ratchets customer payment terms down to normal levels. By limiting purchases, accounts payable also decline. These measures, salutary in the short term, have the paradoxical effect of inflating working capital because certain items remain stubbornly high while accounts payable decline.

As a result, the company produces (and sells) below capacity, causing unit costs to rise and the bottom line to deteriorate.

Finally, in the third phase, the company returns to a sound footing:

- sales surpass production;

- the cap on purchases has stabilised raw material inventories. When purchases return to their normal level, the company again benefits from a “normal” level of supplier credit.

Against this background, working capital stabilises at a low level that is once again proportional to sales, but only after a crisis that might last as long as a year.

It is important to recognise that any contraction strategy, regardless of the method chosen, requires a certain period of psychological adjustment. Management must be convinced that the company is moving from a period of expansion to a period of recession. This psychological change may take several weeks, but once it is accomplished, the company can:

- decrease purchases;

- adjust production to actual sales;

- reduce supplier credit which the company had tried to maximise. Of course, this slows down the reduction in working capital.

We have seldom seen a company take less than nine months to significantly reduce its working capital and improve the bottom line (unless it liquidates inventories at fire-sale prices).

3. Value chain integration strategies

Companies that expand vertically by acquiring suppliers or distributors lengthen their production cycle. In so doing, they increase their value added. But this very process also increases their working capital because the increased value added is incorporated in the various line items that make up working capital, notably receivables and finished goods inventories. Conversely, accounts payable reflect purchases made further upstream and therefore contain less value added. So they become proportionately lower.

4. Negative working capital

The operating cycles of companies with negative working capital are such that, thanks to a favourable timing mismatch, they collect funds prior to disbursing some payments. There are two basic scenarios:

- supplier credit is much greater than inventory turnover, while at the same time customers pay quickly, in some cases in cash: food retailing, e-commerce companies, motorways, companies with very short production cycles like newspaper or bread companies, companies whose suppliers are in a position of such weakness – printers or hauliers that face stiff competition, for example – that they are forced to offer inordinately long payment terms to their customers;

- customers pay in advance. This is the case for companies that work on military contracts, collective catering companies, companies that sell subscriptions, etc. Nevertheless, these companies are sometimes required to lock up their excess cash for as long as the customer has not yet “consumed” the corresponding service. In this case, negative working capital offers a way of earning significant investment income rather than presenting a source of funding that can be freely used by the firm to finance its operations.

A low or negative working capital is a boon to a company looking to expand without recourse to external capital. Efficient companies, in particular in mass-market retailing, all benefit from low or negative working capital. Put another way, certain companies are adept at using intercompany credit to their best advantage.

The presence of negative working capital can, however, lead to management errors. We once saw an industrial group that was loathe to sell a loss-making division because it had a negative working capital. Selling the division would have shored up the group’s profitability but would also have created a serious cash management problem, because the negative working capital of the unprofitable division was financing the working capital of the profitable divisions. Short-sightedness blinded the company to everything but the cash management problem it would have had immediately after the disposal. Recurring losses were disregarded.

We have seen companies with negative working capital, losing money at the operating level, that were able to survive because of a strong growth in sales. Consequently, inflows generated by increasingly negative working capital with growth in revenues allowed them to pay for the operating deficit. The wake-up call is pretty tough when growth slows down and payment difficulties appear. Unsurprisingly, no banker is keen to lend money in this scenario.

5. Working capital as an expression of balance of power

Economists have tried to understand the theoretical justification for intercompany credit, as represented by working capital. To begin with, they have found that there are certain minimum technical turnaround times. For example, a customer must verify that the delivery corresponds to his order and that the invoice is correct. Some time is also necessary to actually effect the payment.

But this explains only a small portion of intercompany credit, which varies greatly from one country to another:

Source: Intrum Justitia

Source: Intrum JustitiaSeveral factors can explain the disparity:

- Cultural differences: in Germanic countries, the law stipulates that the title does not pass to the buyer until the seller is paid. This makes generous payment terms much less attractive for the buyer, because as long as his supplier is not paid, he cannot process the raw material.

- Historical factors: in France, Italy and Spain, bank credit was restricted for a long time. Companies whose businesses were not subject to credit restrictions (building, exports, energy, etc.) used their bank borrowing capacity to support companies subject to the restrictions by granting them generous payment terms. Tweaking payment terms was also a way of circumventing price controls in the Mediterranean countries.

- Technical factors: in the USA, suppliers often offer two-part trade credit, where a substantial discount is offered for relatively early payment, such as a 2% discount for payment made within 10 days. Most buyers take this discount. This discount explains the low level of accounts payable in US groups’ balance sheets. As a by-product, failure of a buyer to take this discount could serve as a very strong and early signal of financial distress.

Furthermore, Delaunay and Dietsch (1999) have shown that supplier credit acts as a financial shock absorber for companies in difficulty. For commercial reasons, suppliers feel compelled to support companies whose collateral or financial strength is insufficient (or has become insufficient) to borrow from banks. Suppliers know that they will not have complete control over payment terms. They have unwittingly become bankers and, like bankers, they attempt to limit payment terms on the basis of the back-up represented by the customer’s assets and capital.

That said, it is unhealthy for companies to offer overly generous payment terms to their customers. By so doing, they run a credit risk. Even though the corporate credit manager function is more and more common, even in small companies, credit managers are not in the best position to appreciate and manage this risk. Moreover, intercompany credit is one of the causes of the domino effect in corporate bankruptcies.

How else can we explain why 39% of industrial groups in the Euro Stoxx 50 (i.e. the largest listed European groups) enjoy negative working capital (Airbus, Unilever, SAP, etc.)?

Section 11.4 Analysing capital expenditures (capex)

The following three questions should guide your analysis of the company’s investments:

- What is the state of the company’s plant and equipment?

- What is the company’s capital expenditure policy?

- What are the cash flows generated by these investments?

1. Analysing the company’s current production capacity

The current state of the company’s fixed assets is measured by the ratio2

A very low ratio (less than 30%) indicates that the company’s plant and equipment are probably worn out. In the near term, the company will be able to generate robust margins because depreciation charges will be minimal. But don’t be fooled, this situation cannot last forever. In all likelihood, the company will soon have trouble because its manufacturing costs will be higher than those of its competitors who have modernised their production facilities or innovated. Such a company will soon lose market share and its profitability will decline.

If the ratio is close to 100%, the company’s fixed assets are relatively new, and it will probably be able to reduce its capital expenditure in the next few years.

2. Analysing the company’s investment policy

Through the production process, fixed assets are used up. The annual depreciation charge is supposed to reflect this wearing out. By comparing capital expenditure with depreciation charges, you can determine whether the company is:

- expanding its industrial base by increasing production capacity. In this case, capital expenditure is higher than depreciation as the company invests more than simply to compensate for the annual wearing-out of fixed assets;

- maintaining its industrial base, replacing production capacity as necessary. In this case, capital expenditure approximately equals depreciation as the company invests just to compensate for the annual wearing-out of fixed assets;

- underinvesting or divesting (capital expenditure below depreciation). This situation can only be temporary or the company’s future will be in danger, unless the objective is to liquidate the company.

Comparing capital expenditure with net fixed assets at the beginning of the period gives you an idea of the size of the investment programme with respect to the company’s existing production facilities. A company that invests an amount equal to 50% of its existing net fixed assets is building new facilities worth half what it has at the beginning of the year. This strategy carries certain risks:

- the risk that economic conditions will take a turn for the worse;

- the risk that production costs will be difficult to control (productivity deteriorates);

- technology risks, etc.

3. Analysing the cash flows generated by investments

The theoretical relationship between capital expenditures on the one hand and the cash flow from operating activities on the other is not simple. New fixed assets are combined with those already on the balance sheet, and together they generate the cash flow of the period. Consequently, there is no direct link between operating cash flow and the capital expenditure of the period.

Comparing cash flow from operating activities with capital expenditure makes sense only in the context of overall profitability and the dynamic equilibrium between sources and uses of funds.

The only reason to invest in fixed assets is to generate profits, i.e. positive cash flows. Any other objective turns finance on its head. You must therefore be very careful when comparing the trends in capital expenditure, cash flow and cash flow from operating activities. This analysis can be done by examining the cash flow statement.

Be on the lookout for companies that, for reasons of hubris, grossly overinvest, despite their cash flow from operating activities not growing at the same rate as their investments. Management has lost sight of the all-important criterion that is profitability.

All the above does not mean that capital expenditure should be financed by internal sources only. Our point is simply that a good investment policy grows cash flow at the same rate as capital expenditure. This leads to a virtuous circle of growth, a necessary condition for the company’s financial equilibrium, as shown in graph A in this figure:

Graphs B, C and D illustrate other corporate situations. In D, investment is far below the company’s cash flow from operations. You must compare investment with depreciation charges so as to answer the following questions:

- Is the company living off the assets it has already acquired (profit generated by existing fixed assets)?

- Is the company’s production equipment ageing?

- Are the company’s current capital expenditures appropriate, given the rate of technological innovation in the sector?

Naturally, the risk in this situation is that the company is resting on its laurels, and that its technology is falling behind that of its competitors. This will eat into the company’s profitability and, as a result, into its cash flow from operating activities at the very moment it will most need cash in order to make the investments necessary to close the gap vis-à-vis its rivals.

Generally speaking, you must understand that there are certain logical inferences that can be made by looking at the company’s investment policy. If its capital expenditure is very high, then the company is embarking on a project to create significant new value rather than simply growing. Accordingly, future cash flow from operating activities will depend on the profitability of these new investments and is thus highly uncertain.

Lastly, ask yourself the following questions about the company’s divestments: do they represent recurrent transactions, such as the gradual replacement of a rental car company’s fleet of vehicles, or are they one-off disposals? In the latter case, is the company’s insufficient cash flow forcing the company to divest? Or is the company selling old, outdated assets in order to turn itself into a dynamic, strategically rejuvenated company? Is this asset-pruning?

4. Analysing investment carried out through external growth

Companies can grow their fixed asset base either through outright purchases (internal growth) or through acquisition of other companies owning fixed assets (external growth).

There are three main risks behind an external growth policy:

- That of integrating assets and people, which is always easier on paper than in real life. This is the first reason why so many mergers fail to deliver on promises (see Chapter 44).

- That of regular changes in the group perimeter, which complicates its analysis and can hide real difficulties.

- That of having overpaid for acquired companies. By carrying out an analysis of prices paid (see Chapter 31), the external analyst can detect overpayments only if he is provided with enough information by the acquirer.

The frequency of acquisition of other companies gives clues about the concentration inside a sector. The higher the latter, the lower the former.

Section 11.5 Case study: ArcelorMittal3

1. Working capital analysis

The average VAT rate of ArcelorMittal is not disclosed, so we have taken a rate of 20%.

| In days of net sales | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

|

58d | 52d | 54d | 46d | 39d |

|

93d | 88d | 94d | 86d | 81d |

|

55d | 34d | 39d | 33d | 35d |

|

46d | 44d | 51d | 48d | 45d |

ArcelorMittal’s operating working capital has declined sharply in days of sales since 2011, from 58 days in 2011 to 39 days in 2015. This fall of €8bn would only have amounted to €5bn if working capital had been in line with sales. This very good performance is explained by a change in inventories, which account for the whole of this €8bn. 2015 in particular saw the largest drop in sales (−20%) when inventories corrected by write-downs fell as quickly as sales, which shows the great speed at which ArcelorMittal adapted its production in a context that had suddenly deteriorated.

The trade receivables and payables making up working capital remain stable in relative terms. Payment periods are very respectable (35 and 45 days, respectively) and seem to be reliable because the sector in which ArcelorMittal operates is not very seasonal.

2. Capital expenditure analysis

Unsurprisingly, given what’s been happening in the steel industry, which has reduced ArcelorMittal’s cash flow and does nothing to encourage investment, the ratio of net fixed assets to gross assets has fallen from 67% in 2011 to 57% in 2015, although it is not worrying at this stage.

Although in 2011 and 2012 annual investments were about equal to depreciation (around $4.7bn), since 2013, they have stagnated and only represented around three-quarters, mainly allocated to maintenance and improving productivity.

Summary

Questions

Exercises

Answers

Notes

1 Provided competitors have the same balance sheet closing date.

2 Net fixed assets are gross fixed assets minus cumulative depreciation.

3 Financial statements for ArcelorMittal are shown on pages 53, 65 and 155.