Left to its own devices, your 90D can do an excellent job of providing the proper exposure for most scenes. But even a camera as smart as the 90D frequently can benefit from intelligent input. For example, when you shoot with the main light source behind the subject, you end up with backlighting, which can result in an overexposed background and/or an underexposed subject. The Canon 90D recognizes backlit situations nicely, and, in most cases, can properly base exposure on the main subject using the default Evaluative metering mode, producing a decent photo.

But, as a creative photographer, there will be many instances where you would rather not have automatic correction for backlighting. What if you want to underexpose the subject to produce a silhouette effect? The 90D does a poor job of exposing intentional silhouettes and will end up producing unwanted detail in what should have been inky black areas of your image. Fortunately, the camera has metering modes and other exposure options that allow you to produce the image you are looking for. If you’re looking for an extensive exposure range, options like the 90D’s built-in Highlight Tone Priority and Auto Lighting Optimizer features can adjust your exposure as you take photos, preserving detail in the highlights and shadows as required. Your Canon 90D also has the capability of fine-tuning exposure separately for each of the metering modes, so you can consistently add or subtract a little exposure to suit your creative tastes.

This chapter discusses using the full range of the camera’s various shooting modes and exposure controls, so you’ll be better equipped to override the default settings when you want to, or need to, and achieve spot-on exposures that produce the exact image you are looking for, every time.

The 90D gives you a great deal of control over all of these, although composition is entirely up to you. You must still frame the photograph to create an interesting arrangement of subject matter, but all the other parameters are basic functions of the camera. You can let your 90D set them for you automatically, you can fine-tune how the camera applies its automatic settings, or you can make them yourself, manually. The amount of control you have over exposure, sensitivity (ISO settings), color balance, focus, and image parameters like sharpness and contrast make the 90D a versatile tool for creating images.

In the next few pages, I’m going to give you a grounding in one of those foundations, and explain the basics of exposure, either as an introduction or as a refresher course, depending on your current level of expertise. When you finish this chapter, you’ll understand most of what you need to know to take well-exposed photographs creatively in a broad range of situations.

Getting a Handle on Exposure

This section explains the fundamental concepts that go into creating an exposure. If you already know about the role of f/stops, shutter speeds, and sensor sensitivity in determining an exposure, you might want to skip to the next section, which explains how the 90D calculates exposure.

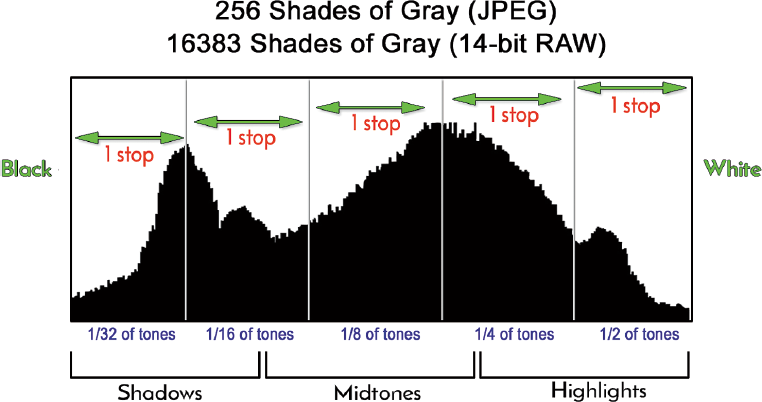

In the most basic sense, exposure is all about light. Exposure can make or break your photo. Correct exposure brings out the detail in the areas you want to picture, providing the range of tones and colors you need to create the desired image. Poor exposure can cloak important details in shadow or wash them out in glare-filled featureless expanses of white. However, getting the perfect exposure requires some intelligence—either that built into the camera or the smarts in your head—because digital sensors can’t capture all the tones we are able to see. If the range of tones in an image is extensive, embracing both inky black shadows and bright highlights, we often must settle for an exposure that renders most of those tones—but not all—in a way that best suits the photo we want to produce.

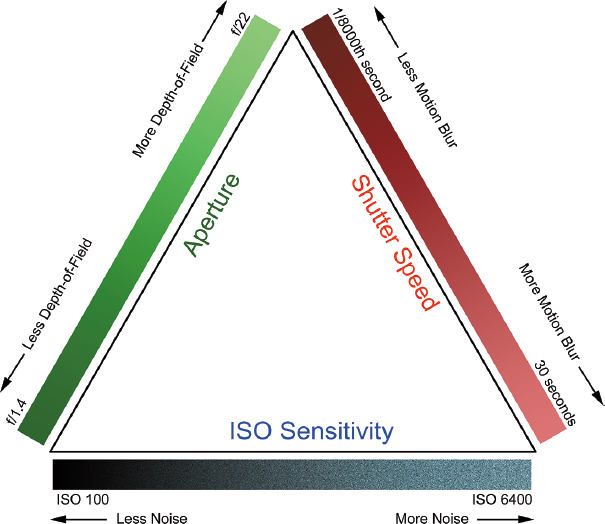

As the owner of a Canon EOS 90D, you’re probably well aware of the traditional “exposure triangle” of aperture (quantity of light, light passed by the lens), shutter speed (the amount of time the shutter is open), and the ISO sensitivity of the sensor—all working proportionately and reciprocally to produce an exposure. The trio is itself affected by the amount of illumination that is available to work with. So, if you double the amount of light, increase the aperture by one stop, make the shutter speed twice as long, or boost the ISO setting 2X, you’ll get twice as much exposure. Similarly, you can increase any one of these factors while decreasing one of the others by a similar amount to keep the same exposure.

Working with any of the three controls involves trade-offs. Larger f/stops provide less depth-of-field, while smaller f/stops increase depth-of-field (and potentially at the same time can decrease sharpness through a phenomenon called diffraction). Shorter shutter speeds do a better job of reducing the effects of camera/subject motion, while longer shutter speeds make that motion blur more likely. Higher ISO settings increase the amount of visual noise and artifacts in your image, while lower ISO settings reduce the effects of noise. (See Figure 4.1.)

Exposure determines the look, feel, and tone of an image, in more ways than one. Incorrect exposure can impair even the best-composed image by cloaking important tones in darkness, or by washing them out so they become featureless to the eye. You’ll often need to make choices about which details are important, and which are not, so that you can grab the tones that truly matter in your image. That’s part of the creativity you bring to bear in realizing your photographic vision.

For example, look at two bracketed exposures presented at top in Figure 4.2. For the image at upper left, there is plenty of detail in the interior of this country store/post office, but the exterior visible through the windows is completely washed out. In the version at top right, taken an instant later using a tripod-mounted camera, the scene outside is well exposed, but the store’s interior is murky and dark. The camera’s sensor simply can’t capture detail in both dark areas and bright areas in a single shot.

With digital camera sensors, it’s tricky to capture detail in both highlights and shadows in a single image, because the number of tones, the dynamic range of the sensor, is limited. The solution, in this particular case, was to resort to a technique called High Dynamic Range (HDR) photography, in which the two exposures from Figure 4.2 were combined in an image editor such as Photoshop, or a specialized HDR tool like Photomatix (about $100 from www.hdrsoft.com). The resulting shot is shown at bottom in Figure 4.2. I’ll explain more about HDR photography later in this chapter. For now, though, I’m going to concentrate on showing you how to get the best exposures possible without resorting to such tools, using only the features of your Canon 90D.

Figure 4.1 The traditional exposure triangle includes aperture, shutter speed, and ISO sensitivity.

Figure 4.2 At upper left, the exposure captures detail in the shadows, but the exterior highlights are washed out. When the image is exposed for the highlights, shadow detail is lost (upper right). Combining the two exposures produces the best compromise image (bottom).

To understand exposure, you need to understand the six aspects of light that combine to produce an image. Start with a light source—the sun, an interior lamp, or the glow from a campfire—and trace its path to your camera, through the lens, and finally to the sensor that captures the illumination. Here’s a brief review of the things within our control that affect exposure.

- Light at its source. Our eyes and our cameras—film or digital—are most sensitive to that portion of the electromagnetic spectrum we call visible light. That light has several important aspects that are relevant to photography, such as color and harshness (which is determined primarily by the apparent size of the light source as it illuminates a subject). But, in terms of exposure, the important attribute of a light source is its intensity. We may have direct control over intensity, which might be the case with an interior light that can be brightened or dimmed. Or, we might have only indirect control over intensity, as with sunlight, which can be made to appear dimmer by introducing translucent light-absorbing or reflective materials in its path.

- Light’s duration. We tend to think of most light sources as continuous. But, as you’ll learn in Chapter 11, the duration of light can change quickly enough to modify the exposure, as when the main illumination in a photograph comes from an intermittent source, such as an electronic flash.

- Light reflected, transmitted, or emitted. Once light is produced by its source, either continuously or in a brief burst, we are able to see and photograph objects by the light that is reflected from our subjects toward the camera lens; transmitted (say, from translucent objects that are lit from behind); or emitted (by a candle or television screen). When more or less light reaches the lens from the subject, we need to adjust the exposure. This part of the equation is under our control to the extent we can increase the amount of light falling on or passing through the subject (by adding extra light sources or using reflectors), or by pumping up the light that’s emitted (by increasing the brightness of the glowing object).

- Light passed by the lens. Not all the illumination that reaches the front of the lens makes it all the way through. Filters can remove some of the light before it enters the lens. Inside the lens barrel is a variable-sized diaphragm that dilates and contracts to vary the size of the aperture and control the amount of light that enters the lens. You, or the 90D’s autoexposure system, can control exposure by varying the size of the aperture. The relative size of the aperture is called the f/stop (see Figure 4.3).

- Light passing through the shutter. Once light passes through the lens, the amount of time the sensor receives it is determined by the 90D’s shutter, which can remain open for as long as 30 seconds (or even longer if you use the Bulb setting) or as briefly as 1/8000th second (or 1/16000th second when using the electronic shutter in Live View mode).

- Light captured by the sensor. Not all the light falling onto the sensor is captured. If the number of photons reaching a particular photosite doesn’t pass a set threshold, no information is recorded. Similarly, if too much light illuminates a pixel in the sensor, then the excess isn’t recorded or, worse, spills over to contaminate adjacent pixels. We can modify the minimum and maximum number of pixels that contribute to image detail by adjusting the ISO setting. At higher ISOs, the incoming light is amplified to boost the effective sensitivity of the sensor.

These factors all work proportionately and reciprocally to produce an exposure. That is, if you double the amount of light that’s available, increase the aperture by one stop, make the shutter speed twice as long, or boost the ISO setting 2X, you’ll get twice as much exposure.

F/STOPS AND SHUTTER SPEEDS

If you’re really new to more advanced cameras (and I realize that many soon-to-be-ambitious photographers do purchase the 90D as their first digital SLR), you might need to know that the lens aperture, or f/stop, is a ratio, much like a fraction, which is why f/2 is larger than f/4, just as 1/2 is larger than 1/4. However, f/2 is actually four times as large as f/4. (If you remember your high school geometry, you’ll know that to double the area of a circle, you multiply its diameter by the square root of two: 1.4.)

Lenses are usually marked with intermediate f/stops that represent a size that’s twice as much/half as much as the previous aperture. So, a lens might be marked f/2, f/2.8, f/4, f/5.6, f/8, f/11, f/16, or f/22, with each larger number representing an aperture that admits half as much light as the one before, as shown in Figure 4.3.

Shutter speeds are actual fractions (of a second), but the numerator is omitted, so that 60, 125, 250, 500, 1000, and so forth represent 1/60th, 1/125th, 1/250th, 1/500th, and 1/1000th second. To avoid confusion, Canon uses quotation marks to signify longer exposures: 2”, 2”5, 4”, and so forth representing 2.0-, 2.5-, and 4.0-second exposures, respectively.

Figure 4.3 Top row (left to right): f/4, f/5.6, f/8; bottom row: f/11, f/16, f/22.

Equivalent Exposure

One of the most important aspects in this discussion is the concept of equivalent exposure. This term means that exactly the same amount of light will reach the sensor at various combinations of aperture and shutter speed. Whether we use a small aperture (large f/number) with a long shutter speed or a wide aperture (small f/number) with a fast shutter speed, the amount of light reaching the sensor can be exactly the same. Table 4.1 shows equivalent exposure settings using various shutter speeds and f/stops; in other words, any of the combination of settings listed will produce exactly the same exposure.

Most commonly, exposure settings are made using the aperture and shutter speed, followed by adjusting the ISO sensitivity if it’s not possible to get the preferred exposure; that is, the one that uses the “best” f/stop or shutter speed for the depth-of-field (range of sharp focus) or action stopping we want (produced by short shutter speeds, as I’ll explain later).

TABLE 4.1 Equivalent Exposures

When the 90D is set for P (Program) mode, the metering system selects the correct exposure for you automatically, but you can change quickly to an equivalent exposure by locking the current exposure, and then spinning the Main Dial until the desired equivalent exposure combination is displayed. You can use this standard Program Shift feature more easily if you remember that you need to rotate the dial toward the left when you want to increase the amount of depth-of-field or use a slower shutter speed; rotate to the right when you want to reduce the depth-of-field or use a faster shutter speed. The need for more/less DOF and slower/faster shutter speed are the primary reasons you’d want to use Program Shift. I’ll explain Program mode exposure shifting options in more detail later in this chapter.

In Aperture-priority (Av) and Shutter-priority (Tv) modes, you can change to an equivalent exposure using a different combination of shutter speed and aperture, but only by either adjusting the aperture in Aperture-priority mode (the camera then chooses the shutter speed) or shutter speed in Shutter-priority mode (the camera then selects the aperture). I’ll cover all these exposure modes and their differences later in the chapter.

F/STOPS VERSUS STOPS

In photography parlance, f/stop always means the aperture or lens opening. However, for lack of a current commonly used word for one exposure increment, the term stop is often used. In the past, EV (Exposure Value) served this purpose, and was used as a measure of the total sensitivity range of a device such as a light meter, but exposure value and its abbreviation have since been inextricably intertwined with its use in describing exposure compensation. In this book, when I say “stop” by itself (no f/), I mean one whole unit of exposure, and am not necessarily referring to an actual f/stop or lens aperture. So, adjusting the exposure by “one stop” can mean changing to the next shutter speed increment (say, from 1/125th second to 1/200th second) or the next aperture (such as f/4 to f/5.6). Similarly, 1/3-stop or 1/2-stop increments can mean either shutter speed or aperture changes, depending on the context. Be forewarned.

How the 90D Calculates Exposure

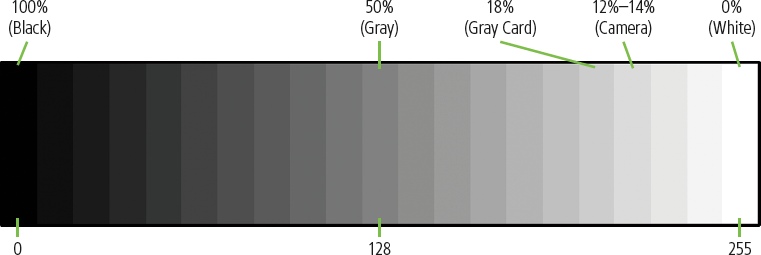

When using the optical viewfinder, your Canon 90D calculates exposure by measuring the light that passes through the lens and is bounced up by the mirror to a 220,000-pixel RGB plus IR-sensitive metering sensor located near the focusing surface. (Note: In live view, the sensor image is used instead, as I’ll explain later.) Light is evaluated using a pattern you can select (more on that later) and based on the assumption that each area being measured reflects about the same amount of light as a neutral gray card that reflects a “middle” gray of about 12 to 18 percent reflectance. (The photographic “gray cards” you buy at a camera store have an 18 percent gray tone, which does represent middle gray; however, your camera is calibrated to interpret a somewhat darker 12 percent gray; I’ll explain more about this later.) That “average” 12 to 18 percent gray assumption is necessary, because different subjects reflect different amounts of light. In a photo containing, say, a white cat and a dark gray cat, the white cat might reflect five times as much light as the gray cat. An exposure based on the white cat will cause the gray cat to appear to be black, while an exposure based only on the gray cat will make the white cat appear washed out.

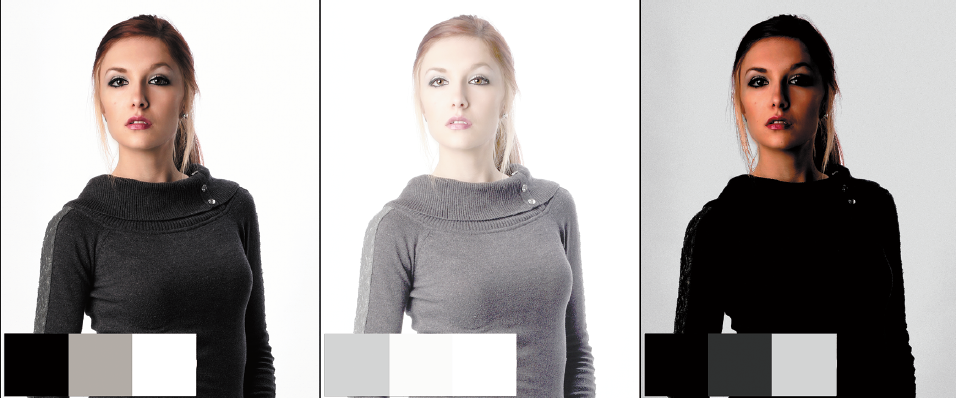

This is more easily understood if you look at some photos of subjects that are dark (they reflect little light), those that have predominantly middle tones, and subjects that are highly reflective. The next few figures show a simplified scale with a middle gray 18 percent tone, plus black and white patches, along with a human figure (not a cat) to illustrate how different exposure measurements actually do affect an exposure.

Correctly Exposed

The image shown in Figure 4.4, left, represents how a photograph might appear if you inserted the patches shown at bottom left into the scene, and then calculated exposure by measuring the light reflecting from the middle gray patch, which, for the sake of illustration, we’ll assume reflects approximately 12 to 18 percent of the light that strikes it. The exposure meter in the camera sees an object that it thinks is a middle gray (the middle patch), calculates an exposure based on that, and the patch in the center of the strip is rendered at its proper tonal value. Best of all, because the resulting exposure is correct, the black patch at left and white patch at right are rendered properly as well.

When you’re shooting pictures with your 90D camera, and the meter happens to base its exposure on a subject that averages that “ideal” middle gray, then you’ll end up with similar (accurate) results. The camera’s exposure algorithms are concocted to ensure this kind of result as often as possible, barring any unusual subjects (that is, those that are backlit, or have uneven illumination). The camera has five different metering modes (described in an upcoming section), each of which is equipped to handle certain types of unusual subjects, as I’ll outline.

Overexposed

Figure 4.4, center, shows what would happen if the exposure were calculated based on metering the leftmost, black patch, which is roughly the same tonal value of the darkest areas of the subject’s hair. The light meter sees less light reflecting from the black square than it would see from a gray middle-tone subject, and so figures, “Aha! I need to add exposure to brighten this subject up to a middle gray!” That lightens the “black” patch, so it now appears to be gray.

But now the patch in the middle that was originally middle gray is overexposed and becomes light gray. And the white square at right is now seriously overexposed and loses detail in the highlights, which have become a featureless white. Our human subject is similarly overexposed. You should always be aware when overexposure occurs but note that it’s not always a bad thing. Some slight overexposures add a dreamy look to an image; once you know how the rules are derived, you’ll know how and when to break them.

Figure 4.4 Exposure based on the middle-gray tone in the center of the card is accurate (left). Metering the black square, the black patch looks gray, the gray patch appears to be a light gray, and the white square is seriously overexposed (center). With exposure calculated from the white patch, the photo is underexposed (right).

Underexposed

The third possibility in this simplified scenario is that the light meter might measure the illumination bouncing off the white patch and try to render that tone as a middle gray. A lot of light is reflected by the white square, so the exposure is reduced, bringing that patch closer to a middle-gray tone. The patches that were originally gray and black are now rendered too dark. Clearly, measuring the gray card—or a substitute that reflects about the same amount of light—is the only way to ensure that the exposure is precisely correct. (See Figure 4.4, right.)

As you can see, the ideal way to measure exposure is to meter from a subject that reflects 12 to 18 percent of the light that reaches it. If you want the most precise exposure calculations, the solution is to use a stand-in, such as the evenly illuminated gray card I mentioned earlier. But, because the standard Kodak gray card reflects 18 percent of the light that reaches it and, as I said, your camera is calibrated for a somewhat lighter 12 percent tone, you would need to add about one-half stop more exposure than the value metered from the card. Of course, in most situations, it’s not necessary to do this. Your camera’s light meter will do a good job of calculating the right exposure, especially if you use the exposure tips in the next section. But I felt that explaining exactly what is going on during exposure calculation would help you understand how your camera’s metering system works.

In some very bright scenes (like a snowy landscape or a lava field), you won’t have a mid-tone to meter. Another substitute for a gray card is the palm of a human hand (the backside of the hand is too variable). But a human palm, regardless of ethnic group, is even brighter than a standard gray card, so instead of one-half stop more exposure, you need to add one additional stop. That is, if your meter reading is 1/500th of a second at f/11, use 1/500th second at f/8 or 1/200th second at f/11 instead. (Both exposures are equivalent.)

Or you might want to resort to using an evenly illuminated gray card mentioned earlier. Small versions are available that can be tucked in a camera bag. Place it in your frame near your main subject, facing the camera, and with the exact same even illumination falling on it that is falling on your subject. Then, use the Spot metering function (described in the next section) to calculate exposure.

In serious photography, you’ll want to choose the metering mode (the pattern that determines how brightness is evaluated) and the exposure mode (determines how the appropriate shutter speed and aperture is set). I’ll describe both aspects in later sections.

ORIGIN OF THE 18 PERCENT “MYTH”

Why are so many photographers under the impression that camera light meters are calibrated to the 18 percent “standard,” rather than the true value, which may be 12 to 14 percent, depending on the vendor? You’ll find this misinformation in an alarming number of places. I’ve seen the 18 percent “myth” taught in camera classes; I’ve found it in books, and even been given this wrong information from the technical staff of camera vendors. (They should know better—the same vendors’ engineers who design and calibrate the cameras have the right figure.)

The most common explanation is that during a revision of Kodak’s instructions for its gray cards in 1977, the advice to open up an extra half stop was omitted, and a whole generation of shooters grew up thinking that a measurement off a gray card could be used as-is. Kodak restored the proviso in 1997 during the next update of the instructions but by then it was too late.

EXTERNAL METERS CAN BE CALIBRATED

The light meters built into your 90D are calibrated at the factory. But if you use a handheld incident or reflective light meter, you can calibrate it, using the instructions supplied with your meter. Because a handheld meter can be calibrated to the 18 percent gray standard (or any other value you choose), my rant about the myth of the 18 percent gray card doesn’t apply.

The Importance of ISO

Another essential concept when discussing exposure, ISO control allows you to change the sensitivity of the camera’s imaging sensor. Sometimes photographers forget about this option, because the common practice is to set the ISO once for a particular shooting session (say, at ISO 100 or 200 for bright sunlight outdoors, or ISO 800 or 1600 when shooting indoors) and then forget about ISO. Or some shooters simply leave the camera set to ISO Auto. That enables the camera to change the ISO it deems necessary, setting a low ISO in bright conditions or a higher ISO in a darker location. That’s fine, but sometimes you’ll want to set a specific ISO yourself. That will be essential sometimes, since ISO Auto cannot set the highest ISO levels that are available when you use manual ISO selection.

TIPWhen shooting in the Program (P), Aperture-priority (Av), and Shutter-priority (Tv) modes, all discussed soon, changing the ISO does not change the exposure. If you switch from using ISO 100 to ISO 1600 in Av mode, for example, the camera will simply set a different shutter speed. If you change the ISO in Tv mode, the camera will set a different aperture, and in P mode, it will set a different aperture and/or shutter speed. In all of these examples, the camera will maintain the same exposure. If you want to make a brighter or a darker photo in P, Av, or Tv mode, you will need to set + or – exposure compensation, as discussed later.

However, when you use the Manual (M) mode, changing the ISO also changes the exposure, as discussed shortly.

The camera provides the best possible image quality in the ISO 100 to 400 range. We use higher ISO levels such as ISO 1600 in low light and ISO 6400 in a very dark location because it allows us to shoot at a faster shutter speed. That’s often useful for minimizing the risk of blurring caused by camera shake, which can occur even with lenses that include image stabilization (IS). And, of course, you must also contend with movement of the subject, which no amount of image stabilization will fix.

Although you can set a desired ISO level yourself, the 90D also offers an ISO Auto option. When enabled, the camera will select an ISO that should be suitable for the conditions: a low ISO on a sunny day and a high ISO in a dark location.

Over the past few years, there has been something of a competition among the manufacturers of digital cameras to achieve the highest ISO ratings. The highest announced ISO numbers have been rising annually, from 1600 to 3200 and 6400; a few cameras even allow you to choose a sensitivity setting that tops 3.2 million. Canon is a bit more conservative, but the 90D offers all the ISO options you’re ever likely to need, up to 25600, expandable to H, the equivalent of ISO 51200. Obviously, the loftiest numbers come at the cost of increased contrast and grain.

Choosing a Metering Method

To calculate exposure automatically, you need to tell the 90D where in the frame to measure the light (this is called the metering method) and what controls should be used (aperture, shutter speed, or both) to set the exposure. That’s called exposure mode and includes Program (P), Shutter-priority (Tv), Aperture-priority (Av), or Manual (M) options, plus Auto and Creative Auto. I’ll explain all these next.

But first, I’m going to introduce you to the four metering methods. You can select any of the four if you’re working with P, Tv, Av, or M exposure modes; if you’re using Auto or Creative Auto, Evaluative metering is selected automatically and cannot be changed.

- 1. Press the Metering Mode button on the top of the camera. You can also press the Q button or tap the Q icon on the shooting settings screen to access the Quick Control menu, where a Metering Mode icon resides. (The Metering Mode button is a lot faster.)

- 2. Use the touch screen or left/right multi-controller buttons to highlight Evaluative, Partial, Spot, or Center-weighted averaging.

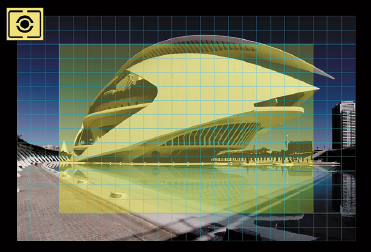

- Evaluative. This mode is the best all-purpose metering method for most pictures. See Figure 4.5 for an example of a scene that can be easily interpreted by the Evaluative metering mode. This mode operates in two different ways:

- When using the viewfinder. The 90D uses its 220,000-pixel exposure sensor, which detects a full range of RGB colors, plus infrared. (The RGB capability is important for face detection, as I’ll explain shortly.) A 216-zone array, covering roughly 56 percent of the frame (represented by the yellow shading in Figure 4.5), is analyzed.

- In Live View and Movie mode. Exposure is measured directly from the sensor instead, using a 384-zone array that covers the full frame.

In either case, the individual zones used are linked to the autofocus points currently in use. The camera evaluates the data, giving extra emphasis to the metering zones that indicate sharp focus to make an educated guess about what kind of picture you’re taking, based on examination of thousands of different real-world photos. For example, if the top sections of a picture are much lighter than the bottom portions, the algorithm can assume that the scene is a landscape photo with lots of sky.

- Evaluative. This mode is the best all-purpose metering method for most pictures. See Figure 4.5 for an example of a scene that can be easily interpreted by the Evaluative metering mode. This mode operates in two different ways:

Figure 4.5 Evaluative metering uses multiple zones linked to the autofocus points.

Figure 4.6 Partial metering allows measuring exposure from the central area of the image, while giving less emphasis to the darker areas at top and bottom.

-

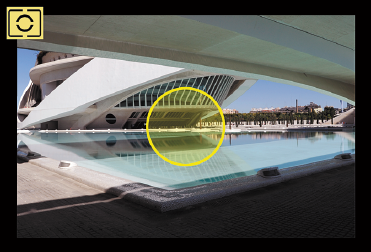

- Partial. Use this mode if the background is much brighter or darker than the subject, as in Figure 4.6. This is a faux spot mode, using the center of the frame and encompassing roughly 6.5 percent of the total image area (4.5 percent when using Live View) to calculate exposure, which, as you can see in Figure 4.6, is a rather large spot, represented by the yellow circle. The status LCD icon is shown in the upper-left corner.

Figure 4.7 Spot metering allows calculating exposure exclusively from the middle gray structural components.

-

- Spot. This mode is useful when you want to base exposure on a small area in the frame, such as a spot-lit performer, or an image with multiple bright and dark areas like the scene shown in Figure 4.7. This mode confines the reading to a limited area in the center of the viewfinder, as shown in the figure, making up only 2 percent of the image (2.6 percent in live view). If that area is in the center of the frame, so much the better. If not, you’ll have to make your meter reading and then lock exposure by pressing the shutter release halfway, or by pressing the AE lock button.

Figure 4.8 Center-weighted averaging is useful for images with the most important detail in the center of the frame.

-

- Center-weighted averaging. Center-weighted averaging works best for portraits, architectural photos, and other pictures in which the most important subject is located in the middle of the frame, as in Figure 4.8. In this mode, the exposure meter emphasizes a zone in the center of the frame to calculate exposure, as shown in the figure, on the theory that, for most pictures, the main subject will be located in the center. As the name suggests, the light reading is weighted toward the central portion, but information is also used from the rest of the frame. If your main subject is surrounded by very bright or very dark areas, the exposure might not be exactly right. However, this scheme works well in many situations if you don’t want to use one of the other modes.

- 3. Choose SET to confirm your choice.

Choosing an Exposure Method

You’ll find four Creative Zone methods for choosing the appropriate shutter speed and aperture: Program (P), Shutter-priority (Tv), Aperture-priority (Av), and Manual (M). To select one of these modes, just spin the Mode Dial (located at the top-left side of the camera) to choose the method you want to use. You can also select from the Basic Zone exposure methods, which provide much less control.

Your choice of which exposure method is best for a given shooting situation will depend on things like your need for lots of (or less) depth-of-field, a desire to freeze action or allow motion blur, or how much noise you find acceptable in an image. Each of the 90D’s exposure methods emphasizes one of those aspects of image capture or another. This section introduces you to all of them.

Basic Zone Exposure Methods

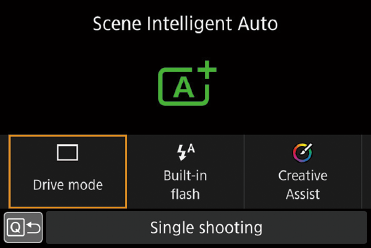

When using Basic Zone modes, you have little control over exposure. In any of these modes, the 90D sets Evaluative metering for you, and chooses the shutter speed and aperture automatically. Indeed, when using Scene modes, you can’t change any of the other shooting settings (other than image quality).

In Scene Intelligent Auto mode, the 90D selects an appropriate ISO sensitivity setting, color (white) balance, Picture Style, color space, noise reduction features, and use of the Auto Lighting Optimizer. (All of these will be discussed in Chapter 7.)

Aperture-Priority

In Av mode, you specify the lens opening used, and the 90D selects the shutter speed. Aperture-priority is especially good when you want to use a particular lens opening to achieve a desired effect. Perhaps you’d like to use the smallest f/stop possible to maximize depth-of-field in a close-up picture. Or you might want to use a large f/stop to throw everything except your main subject out of focus, as in Figure 4.9. Maybe you’d just like to “lock in” a particular f/stop smaller than the maximum aperture because it’s the sharpest available aperture with that lens. Or, you might prefer to use, say, f/2.8 on a lens with a maximum aperture of f/1.4, because you want the best compromise between speed and sharpness.

Figure 4.9 Use Aperture-priority to “lock in” a large f/stop when you want to blur the background.

Aperture-priority can even be used to specify a range of shutter speeds you want to use under varying lighting conditions, which seems almost contradictory. But think about it. You’re shooting a soccer game outdoors with a telephoto lens and want a relatively high shutter speed, but you don’t care if the speed changes a little should the sun duck behind a cloud. Set your 90D to Av, and adjust the aperture until a shutter speed of, say, 1/1000th second is selected at your current ISO setting. (In bright sunlight at ISO 400, that aperture is likely to be around f/11.) Then, go ahead and shoot, knowing that your 90D will maintain that f/11 aperture (for sufficient DOF as the soccer players move about the field), but will drop down to 1/750th or 1/500th second if necessary should the lighting change a little.

A blinking 30 or 8000 in the viewfinder indicates that the 90D is unable to select an appropriate shutter speed at the selected aperture and that over- and underexposure will occur at the current ISO setting. That’s the major pitfall of using Av: you might select an f/stop that is too small or too large to allow an optimal exposure with the available shutter speeds. For example, if you choose f/2.8 as your aperture and the illumination is quite bright (say, at the beach or in snow), even your camera’s fastest shutter speed might not be able to cut down the amount of light reaching the sensor to provide the right exposure. Or, if you select f/8 in a dimly lit room, you might find yourself shooting with a very slow shutter speed that can cause blurring from subject movement or camera shake. Aperture-priority is best used by those with a bit of experience in choosing settings. Many seasoned photographers leave their 90D set on Av all the time.

When to use Aperture-priority:

- General landscape photography. The 90D is a great camera for landscape photography, of course, because its 32.5 MP of resolution allows making huge, gorgeous prints, as well as smaller prints that are filled with eye-popping detail. Aperture-priority is a good tool for ensuring that your landscape is sharp from foreground to infinity, if you select an f/stop that provides maximum depth-of-field.

If you use Av mode and select an aperture like f/11 or f/16, it’s your responsibility to make sure the shutter speed selected is fast enough to avoid losing detail to camera shake, or that the 90D is mounted on a tripod. One thing that new landscape photographers fail to account for is the movement of distant leaves and tree branches. When seeking the ultimate in sharpness, go ahead and use Aperture-priority, but boost ISO sensitivity a bit, if necessary, to provide a sufficiently fast shutter speed, whether shooting handheld or with a tripod.

- Specific landscape situations. Aperture-priority is also useful when you have no objection to using a long shutter speed, or, particularly, want the 90D to select one. Waterfalls are a perfect example. You can use Av mode, set your camera to ISO 100, use a small f/stop, and let the camera select a longer shutter speed that will allow the water to blur as it flows. Indeed, you might need to use a neutral-density filter to get a sufficiently long shutter speed. But Aperture-priority mode is a good start.

- Portrait photography. Portraits are the most common applications of selective focus. A medium-large aperture (say, f/5.6 or f/8) with a longer lens/zoom setting (in the 85mm–135mm range) will allow the background behind your portrait subject to blur. A very large aperture (I frequently shoot wide open with my 85mm f/1.2 lens) lets you apply selective focus to your subject’s face. With a three-quarters view of your subject, as long as their eyes are sharp, it’s okay if the far ear or their hair is out of focus.

- When you want to ensure optimal sharpness. All lenses have an aperture or two at which they perform best, providing the level of sharpness you expect from a camera with the resolution of the 90D. That’s usually about two stops down from wide open, and thus will vary depending on the maximum aperture of the lens. My 85mm f/1.2 is good wide open, but it’s even sharper at f/2.8 or f/4; I shoot my 70-200mm f/2.8 wide open at concerts, but, if I can use f/4 instead, I’ll get better results. Aperture-priority allows me to use each lens at its very best f/stop.

- Close-up/Macro photography. Depth-of-field is typically very shallow when shooting macro photos, and you’ll want to choose your f/stop carefully. Perhaps you need the smallest aperture you can get away with to maximize DOF. Or you might want to use a wider stop to emphasize your subject, as I did with the photo of the roseate spoonbill in Figure 4.9. Av mode comes in very useful when shooting close-up pictures. Because macro work is frequently done with the 90D mounted on a tripod, and your close-up subjects, if not living creatures, may not be moving much, a longer shutter speed isn’t a problem. Aperture-priority (Av mode) can be your preferred choice.

Shutter-Priority

Shutter-priority (Tv) is the inverse of Aperture-priority: you choose the shutter speed you’d like to use, and the camera’s metering system selects the appropriate f/stop. Perhaps you’re shooting action photos and you want to use the absolute fastest shutter speed available with your camera; in other cases, you might want to use a slow shutter speed to add some blur to a ballet photo that would be mundane if the action were completely frozen. Shutter-priority mode gives you some control over how much action-freezing capability your digital camera brings to bear in a particular situation, as you can see in Figure 4.10.

You’ll also encounter the same problem as with Aperture-priority when you select a shutter speed that’s too long or too short for correct exposure under some conditions. I’ve shot outdoor soccer games on sunny fall evenings and used Shutter-priority mode to lock in a 1/1000th second shutter speed, which triggered the blinking warning, even with the lens wide open.

Like Av mode, it’s possible to choose an inappropriate shutter speed. If that’s the case, the maximum aperture of your lens (to indicate underexposure) or the minimum aperture (to indicate overexposure) will blink.

When to use Shutter-priority:

- To reduce blur from subject motion. Set the shutter speed of the 90D to a higher value to reduce the amount of blur from subjects that are moving. The exact speed will vary depending on how fast your subject is moving and how much blur is acceptable. You might want to freeze a basketball player in mid-dunk with a 1/1000th second shutter speed, or use 1/250th second to allow the spinning wheels of a motocross racer to blur a tiny bit to add the feeling of motion.

- To add blur from subject motion. There are times when you want a subject to blur, say, when shooting waterfalls with the camera set for a one- or two-second exposure in Shutter-priority mode.

- To add blur from camera motion when you are moving. Say you’re panning to follow a pair of relay runners. You might want to use Shutter-priority mode and set the 90D for 1/60th second, so that the background will blur as you pan with the runners. The shutter speed will be fast enough to provide a sharp image of the athletes.

- To reduce blur from camera motion when you are moving. In other situations, the camera may be in motion, say, because you’re shooting from a moving train or auto, and you want to minimize the amount of blur caused by the motion of the camera. Shutter-priority is a good choice here, too.

Figure 4.10 Lock the shutter at a slow speed to introduce a little blur into a shot, as seen here in the flying fingers of ukulele virtuoso Jake Shimabukuro.

- Landscape photography handheld. If you can’t use a tripod for your landscape shots, you’ll still probably want the sharpest image possible. Shutter-priority can allow you to specify a shutter speed that’s fast enough to reduce or eliminate the effects of camera shake. Just make sure that your ISO setting is high enough that the 90D will select an aperture with sufficient depth-of-field, too.

- Concerts and stage performances. I shoot a lot of concerts with my 70-200mm f/2.8 lens, and have discovered that, when image stabilization is taken into account, a shutter speed of 1/180th second is fast enough to eliminate the effects of camera shake from handholding the 90D with this lens, and also to avoid blur from the movement of all but the most energetic performers. I use Shutter-priority and set the ISO so the camera will select an aperture in the f/4–5.6 range.

Program Mode

Program mode (P) uses the 90D’s built-in smarts to select the correct f/stop and shutter speed using a database of picture information that tells it which combination of shutter speed and aperture will work best for a particular photo. If the correct exposure cannot be achieved at the current ISO setting, the shutter speed or aperture indicator in the viewfinder will blink, indicating under- or overexposure. You can then boost or reduce the ISO to increase or decrease sensitivity.

The 90D’s recommended exposure can be overridden if you want. Use the EV setting feature (described later, because it also applies to Tv and Av modes) to add or subtract exposure from the metered value. And, as I mentioned earlier in this chapter, you can change from the recommended setting to an equivalent setting (as shown in Table 4.1) that produces the same exposure, but using a different combination of f/stop and shutter speed. To accomplish this:

- 1. Press the shutter release halfway to lock in the current base exposure, or press the AE lock button (*) on the back of the camera (in which case the * indicator will illuminate in the viewfinder to show that the exposure has been locked).

- 2. Spin the Main Dial to change the shutter speed (the 90D will adjust the f/stop to match).

Your adjustment remains in force for a single exposure; if you want to change from the recommended settings for the next exposure, you’ll need to repeat those steps.

When to use Program mode priority:

- When you’re in a hurry to get a grab shot. The 90D will do a pretty good job of calculating an appropriate exposure for you, without any input from you.

- When you hand your camera to a novice. Set the 90D to P, hand the camera to your friend, relative, or trustworthy stranger you meet in front of the Eiffel Tower, point to the shutter release button and viewfinder, and say, “Look through here, and press this button.”

- When no special shutter speed or aperture settings are needed. If your subject doesn’t require special anti- or pro-blur techniques, and depth-of-field or selective focus aren’t important, use P as a general-purpose setting. You can still make adjustments to increase/decrease depth-of-field or add/reduce motion blur with a minimum of fuss.

Manual Exposure

Part of being an experienced photographer comes from knowing when to rely on your 90D’s automation (including Scene Intelligent Auto or P mode), when to go semi-automatic (with Tv or Av), and when to set exposure manually (using M). Some photographers actually prefer to set their exposure manually, as the 90D will be happy to provide an indication of when its metering system judges your settings provide the proper exposure, using the analog exposure scale at the bottom of the view-finder and on the status LCD.

Manual exposure can come in handy in some situations. You might be taking a silhouette photo and find that none of the exposure modes or EV correction features give you exactly the effect you want. For example, when I photographed the sunset shot in Figure 4.11, there was no way any of my 90D’s exposure modes would be able to interpret the scene the way I wanted to shoot it, even with Spot metering, which didn’t have a narrow enough field-of-view from my position. So, I took a couple test exposures, and set the exposure manually using the exact shutter speed and f/stop I needed. You might be working in a studio environment using multiple flash units. The additional flash are triggered by slave devices (gadgets that set off the flash when they sense the light from another flash, or, perhaps from a radio or infrared remote control). Your camera’s exposure meter doesn’t compensate for the extra illumination, and can’t interpret the flash exposure at all, so you need to set the aperture manually.

Depending on your proclivities you might not need to set exposure manually very often, but you should still make sure you understand how it works. Fortunately, the 90D makes setting exposure manually very easy. Just set the Mode Dial to M, turn the Main Dial to set the shutter speed, and rotate the Quick Control Dial to adjust the aperture. Press the shutter release halfway or press the AE lock button, and the exposure scale in the viewfinder shows you how far your chosen setting diverges from the metered exposure.

When to use Manual exposure:

- When working in the studio. If you’re working in a studio environment, you generally have total control over the lighting and can set exposure exactly as you want. The last thing you need is for the 90D to interpret the scene and make adjustments of its own. Use M, and shutter speed, aperture, and (as long as you don’t use ISO-Auto) the ISO setting are totally up to you.

- When using non-dedicated flash. External Canon-dedicated flash units are cool and can even be used to coordinate use of your 90D’s internal flash. But if you’re working with a non-compatible flash unit, particularly studio flash plugged into a PC/X sync adapter mounted on the hot shoe, the camera has no clue about the intensity of the flash, so you’ll have to dial in the appropriate aperture manually.

- If you’re using a handheld light meter. Determining that appropriate aperture, both for flash exposures and shots taken under continuous lighting, can be determined by a handheld light meter, flash meter, or combo meter that measures both kinds of illumination. With an external meter, you can measure highlights, shadows, backgrounds, or additional subjects separately, and use Manual exposure to make your settings.

Figure 4.11 Manual exposure allows selecting both f/stop and shutter speed, especially useful when you’re experimenting, as with this silhouetted sunset shot.

- When you want to outsmart the metering system. Your 90D’s metering system is “trained” to react to unusual lighting situations, such as backlighting, extra-bright illumination, or low-key images with murky shadows. In many cases, it can counter these “problems” and produce a well-exposed image. But what if you don’t want a well-exposed image? Manual exposure allows you to produce silhouettes in backlit situations, wash out all the middle tones to produce a luminous look, or underexpose to create a moody or ominous dark-toned photograph. See Figure 4.11 for an example of an image that required manual exposure to produce the silhouette effect.

Adjusting Exposure with ISO Settings

Another way of adjusting exposures is by changing the ISO sensitivity setting. Sometimes photographers forget about this option, because the common practice is to set the ISO once for a particular shooting session (say, at ISO 100 or 200 for bright sunlight outdoors, or ISO 800 when shooting indoors) and then forget about ISO. ISOs higher than ISO 100 or 200 are seen as “bad” or “necessary evils.” However, changing the ISO is a valid way of adjusting exposure settings, particularly with the Canon EOS 90D, which produces good results at ISO settings that create grainy, unusable pictures with some other camera models.

Indeed, I find myself using ISO adjustment as a convenient alternate way of adding or subtracting EV when shooting in Manual mode, and as a quick way of choosing equivalent exposures when in Auto or semi-automatic modes. For example, I’ve selected a Manual exposure with both f/stop and shutter speed suitable for my image using, say, ISO 200. I can change the exposure in full-stop increments by pressing the ISO button on top of the camera and spinning the Main Dial one click at a time. Rotating to the right increases the ISO sensitivity; to the left reduces it; and spinning all the way to the left selects Auto ISO. The difference in image quality/noise at the base setting of ISO 200 is negligible if I dial in ISO 100 to reduce exposure a little or change to ISO 400 to increase exposure. I keep my preferred f/stop and shutter speed, but still adjust the exposure.

Or, perhaps, I am using Tv mode and the metered exposure at ISO 200 is 1/500th second at f/11. If I decide on the spur of the moment, I’d rather use 1/500th second at f/8, I can press the ISO button and spin the Main Dial to switch to ISO 100. Of course, it’s a good idea to monitor your ISO changes, so you don’t end up at ISO 25600 accidentally. ISO settings can, of course, also be used to boost or reduce sensitivity in particular shooting situations. The 90D can use ISO settings from ISO 100 up to 1600. You can also activate ISO expansion in the ISO Speed Settings entry of the Shooting 2 menu (as described in Chapter 7) to enable settings up to H (ISO 25600 equivalent).

With the 90D, Canon has given you a great deal of control over the ISO settings available for manual or automatic selection:

- Range for Stills. In the ISO Speed Settings entry in the Shooting 2 menu, you can select this option to define the range of sensitivity settings you can choose manually. You can select minimum ISO values from 100 up to 12800 (or a minimum of ISO 200 when Highlight Tone Priority is enabled). A value of 12800 would mean you could not select an ISO setting of less than 12800, which is highly unlikely. More commonly you might want to choose an ISO of 400 or slightly higher minimum when shooting under dim lighting conditions, which would block you from accidentally selecting a lower number. You can also select the highest ISO setting available for manual selection. While ISO 25600 is the default value, you can choose values between 200 and H (25600) in whole stop increments (that is, 200, 400, 800, and so forth). The H setting enables ISO expansion, which may produce excessive noise, irregular colors, banding, and lower resolution. Use H with caution.

- Auto Range. Defining the range used by ISO Auto allows you to put this automated feature to work with some limitations that help avoid unwanted surprises. You can select a minimum value of ISO 100 to ISO 3200, and a maximum of ISO 200 to ISO 25600, and no higher, even when ISO Expansion is enabled. The ISO Auto feature will choose an appropriate ISO setting for you, and display that value on the top-panel LCD when you press the shutter release halfway.

- Minimum Shutter Speed. This setting specifies the minimum shutter speed used for ISO Auto, and not for any other shooting modes. It allows you to select the lowest shutter speed you want used before ISO Auto kicks in.

You can select Auto for shutter speed selection; press SET and then rotate the Main Dial to choose Slower (up to –3) or Faster (up to +3). At the middle (0) value, the minimum shutter speed will be the reciprocal of the lens focal length, i.e., 1/30th second with a 30mm zoom setting. Each value plus or minus 1 to 3 specifies a shutter speed one stop faster or slower, respectively.

Choose Manual, instead, and you can select a minimum shutter speed from 1 second to 1/8000th second using the Main Dial.

When ISO Auto is enabled, the camera can adjust the ISO automatically as appropriate for various lighting conditions. In Basic Zone modes, ISO is normally set between ISO 100 and ISO 6400, except in Landscape mode, where only ISO 100 to ISO 1600 is used, and Handheld Night Scene mode, which uses ISO 100 to ISO 12800.

When using flash, Auto ISO produces a setting of ISO 400 automatically, except when overexposure would occur (as when shooting subjects very close to the camera), in which case a lower setting (down to ISO 100) will be used. If you have an external dedicated flash attached, the 90D can set ISO in the range of 400 to 1600 automatically when using Creative Auto, Portrait, Landscape, Close-Up, Sports, or P exposure modes. That capability can be useful when shooting outdoor field sports at night and other “long distance” flash pictures, particularly with a telephoto lens, because you want to extend the “reach” of your external flash as far as possible (to dozens of feet or more), and boosting the ISO does that. Remember that if the Auto ISO ranges aren’t suitable for you, individual ISO values can also be selected in any of the Creative Zone modes.

TIPFind yourself locked out of ISO settings lower than 200 or higher than 12800? You’ve probably set Highlight Tone Priority to Enable in the Shooting 2 menu, as described in Chapter 7.

Dealing with Visual Noise

Visual image noise is that random grainy effect that some like to use as a special effect, but which, most of the time, is objectionable because it robs your image of detail even as it adds that “interesting” texture. Noise is caused by two different phenomena: high ISO settings and long exposures.

High ISO noise commonly first appears when you raise your camera’s sensitivity setting above ISO 800. With Canon cameras, which are renowned for their good ISO noise characteristics, noise may become visible at ISO 1600, and it is usually fairly noticeable at ISO 3200. At the H setting (ISO 25600 equivalent), noise is usually quite bothersome, which is why that lofty sensitivity rating is disabled by default and must be activated using an option in the ISO Speed Settings entry of the Shooting 2 menu (discussed again in Chapter 7). This kind of noise appears as a result of the amplification needed to increase the sensitivity of the sensor. While higher ISOs do pull details out of dark areas, they also amplify non-signal information randomly, creating noise.

A similar noisy phenomenon occurs during long time exposures, which allow more photons to reach the sensor, increasing your ability to capture a picture under low-light conditions. However, the longer exposures also increase the likelihood that some pixels will register random phantom photons, often because the longer an imager is “hot,” the warmer it gets, and that heat can be mistaken for photons. There’s also a special kind of noise that CMOS sensors like the one used in the 90D are potentially susceptible to. With a CCD, the entire signal is conveyed off the chip and funneled through a single amplifier and analog-to-digital conversion circuit. Any noise introduced there is, at least, consistent. CMOS imagers, on the other hand, contain millions of individual amplifiers and A/D converters, all working in unison. Because all these circuits don’t necessarily process in precisely the same way all the time, they can introduce something called fixed-pattern noise into the image data.

Fortunately, Canon’s electronics geniuses have done an exceptional job minimizing noise from all causes in the 90D. Even so, you might still want to apply the optional long exposure noise reduction. This type of noise reduction involves the 90D taking a second, blank exposure, and comparing the random pixels in that image with the photograph you just took. Pixels that coincide in the two represent noise and can safely be suppressed. This noise reduction system, called dark frame subtraction, effectively doubles the amount of time required to take a picture, and is used only for exposures longer than one second. Noise reduction can reduce the amount of detail in your picture, as some image information may be removed along with the noise. So, you might want to use this feature with moderation. Some types of images don’t require noise reduction, because the grainy pattern tends to blend into the overall scene.

To activate your 90D’s long exposure noise reduction features, go to the Shooting 4 menu, as explained further in Chapter 7.

You can also apply noise reduction to a lesser extent using Photoshop, and when converting RAW files to some other format, using your favorite RAW converter, or an industrial-strength product like Noise Ninja (www.picturecode.com) to wipe out noise after you’ve already taken the picture.

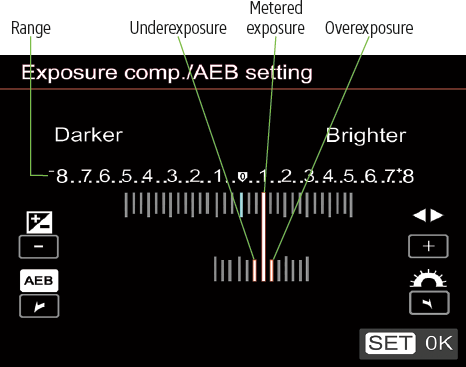

Making EV Changes

Sometimes you’ll want more or less exposure than indicated by the 90D’s metering system. Perhaps you want to underexpose to create a silhouette effect or overexpose to produce a high-key look. It’s easy to use the 90D’s Exposure Compensation system to override the exposure recommendations, available in any Creative Zone mode except Manual. There are two ways to make exposure value (EV) changes with the 90D. One method is fast but limited to display of plus/minus three stops of compensation. The second method is slower but allows setting up to 5 stops of compensation in either 1/3- or full-stop increments.

Fast EV Changes

Activate the exposure meters by tapping the shutter release button. Then, rotate the QCD while looking through the viewfinder or at the back-panel LCD monitor when the Quick Control screen is visible (press the INFO. button to cycle to it, if necessary). Spin to the right to make the image brighter (add exposure), and to the left to make the image darker (subtract exposure). The exposure scale in the viewfinder and on the LCD indicates the EV change you’ve made. The EV change you’ve made remains for the exposures that follow, until you manually zero out the EV setting with the AV button + Main Dial. EV changes are ignored when using M or any of the Basic Zone modes. (If you’re unable to make an adjustment, you may have set the Lock switch to the locked position. Rotate it downward to reactivate the Quick Control Dial.)

Slower EV Changes

You can also use the second method for making EV changes with the 90D. It can be a little slower but allows you to set up to plus/minus five stops of adjustment. You also have the option of setting exposure bracketing at the same time:

- 1. Press the MENU button and navigate to the Expo. Comp./AEB entry in the Shooting 2 menu.

- 2. When the screen appears, use the touch screen, rotate the Quick Control Dial, or press the left/right multi-controller buttons to add or subtract EV adjustment. The screen has helpful labels (Darker on the left and Brighter on the right) to make sure you’re adding/subtracting when you really want to. (See Figure 4.12.) Note that you can also set exposure bracketing, as discussed in Chapter 7, by rotating the Main Dial while viewing this screen. (See Figure 4.13.)

- 3. Choose SET to confirm your choice.

Figure 4.12 EV changes are displayed on the scale in the LCD when using the Shooting 3 menu.

Figure 4.13 The Main Dial can be used to bracket exposures.

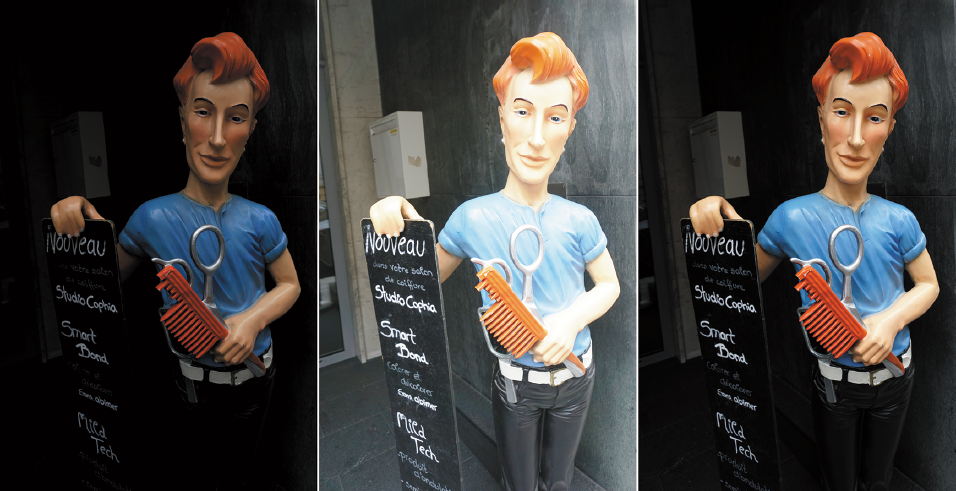

Bracketing Parameters

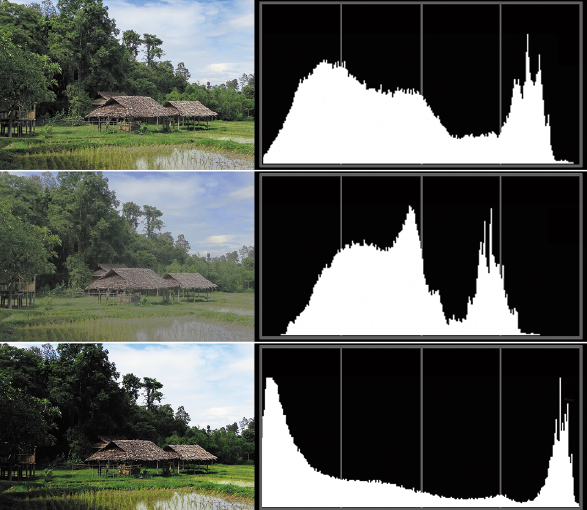

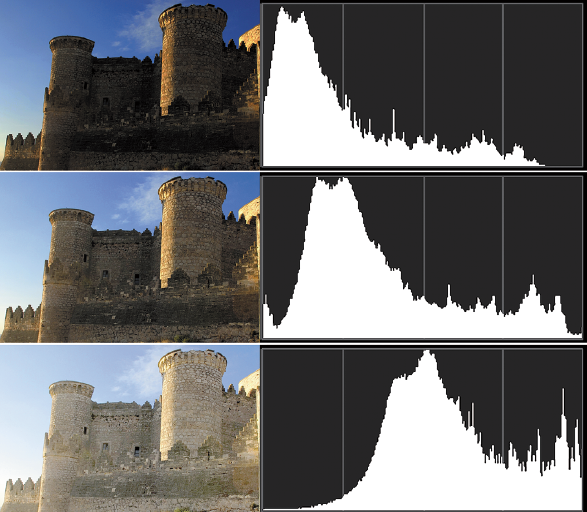

Bracketing is a method for shooting several consecutive exposures using different settings, as a way of improving the odds that one will be exactly right. Before digital cameras took over the universe, it was common to bracket exposures, shooting, say, a series of three photos at 1/125th second, but varying the f/stop from f/8 to f/11 to f/16. In practice, smaller than whole-stop increments were used for greater precision. Plus, it was just as common to keep the same aperture and vary the shutter speed, although in the days before electronic shutters, film cameras often had only whole increment shutter speeds available. Figure 4.14 shows a typical bracketed series.

Today, cameras like the 90D can bracket exposures much more precisely, and bracket white balance as well (using the WB Shift/Bkt entry found in the Shooting 3 menu and described in Chapter 7). While WB bracketing is sometimes used when getting color absolutely correct in the camera is important, autoexposure bracketing (AEB) is used much more often. When this feature is activated, the 90D takes three (and only three) consecutive bracketed photos (immediately if continuous shooting is enabled; otherwise, one at a time as you press the shutter release). It takes one photo at the metered “correct” exposure, one with less exposure, and one with more exposure, using an increment of your choice up to plus 2/minus 2 stops. (Choose between increments by setting Custom Function (C.Fn) I-1 to 0 [1/3 stop] or 1 [1/2 stop].) In Av mode, the shutter speed will change, while in Tv mode, the aperture will change.

Figure 4.14 In this bracketed series you can see underexposure (left), overexposure (center), and metered exposure (right).

Bracketing Auto Cancel

The final relevant entry in the C.Fn I: Exposure menu is 3: Bracketing Auto Cancel. When you activate bracketing (in the Shooting 2 menu, described shortly), the 90D continues to shoot bracketed exposures until you manually turn the bracket feature off, assuming you have this setting disabled. That’s a good thing. If you’re out shooting a series of bracketed exposures (especially for HDR), it’s convenient to have your bracket setting be “sticky” and still be active even if you turn your camera off. Some shooters like to bracket virtually everything and like to leave bracketing on routinely.

However, much of the time you’ll want to turn bracketing off, and you may not want to visit the Shooting 2 menu to deactivate it manually. Set Bracketing Auto Cancel to On, and bracketing is cancelled when you turn the 90D off, change lenses, use the flash, or change memory cards. When this setting is set to Off, bracketing remains in effect until you manually turn it off or use the flash. The flash still cancels bracketing, but your settings are retained.

Bracketing Sequence

Also in the Custom Function menu, you’ll find the C.Fn I-4: Bracketing Sequence entry, which allows you to specify the order in which the autoexposure bracketing series are exposed. Your choice will depend both on personal preference, and what you intend to do with the bracketed shots. The options include:

- 0 - +: The exposure sequence is standard exposure, decreased exposure, increased exposure. With this default value, your base exposure will be captured and saved first on your memory card, followed by the progressively reduced exposure images, then the shots with increased exposure. You might prefer this order if you expect your standard exposure will be the preferred image and arranged first in the queue of each bracket set and want the alternate exposures to follow.

- - 0 +: The sequence is decreased exposure, standard exposure, increased exposure. This order is the most logical to use if you’re shooting with the intention to combine images using HDR (high dynamic range) techniques in your image editor or HDR utility. The final bracketed array is stored on your memory card starting with the most underexposed shot, and progressing to the best exposed, and then on to the overexposures. That makes it easy to use all your bracketed shots in the HDR sequence, or to select only some of them to combine.

- + 0 -: This sequence is the inverse of the last one, progressing from increased exposure to standard exposure and decreased exposure. You might prefer this order if you expect to see your best exposures on the plus side of the exposure sequence and want them to be displayed first.

Number of Exposures

The C.Fn I-5: Number of Bracketed Shots entry allows you to elect to bracket 2, 3, 5, or 7 shots:

- 2 shots. The 90D will capture one image at the base or standard exposure (which can be the metered exposure, or one that’s more or less than the metered exposure, as I’ll explain shortly). It then takes one additional shot that provides either more or less exposure relative to that “base” image. Rotate the QCD to the right to specify more exposure for the second shot, or to the left to specify less exposure. The amount of additional/less exposure is determined by the increment you select. (Read on! I’ll tie all the parameters together in an upcoming section.)

- 3, 5, 7 shots. The camera captures one image at the base exposure, and then two, four, or six shots bracketed around that exposure, respectively. That translates to one over/one under at the 3-shot setting, two over/two under at the 5-shot setting, and three over/three under when using the 7-shot option.

Increment Between Exposures

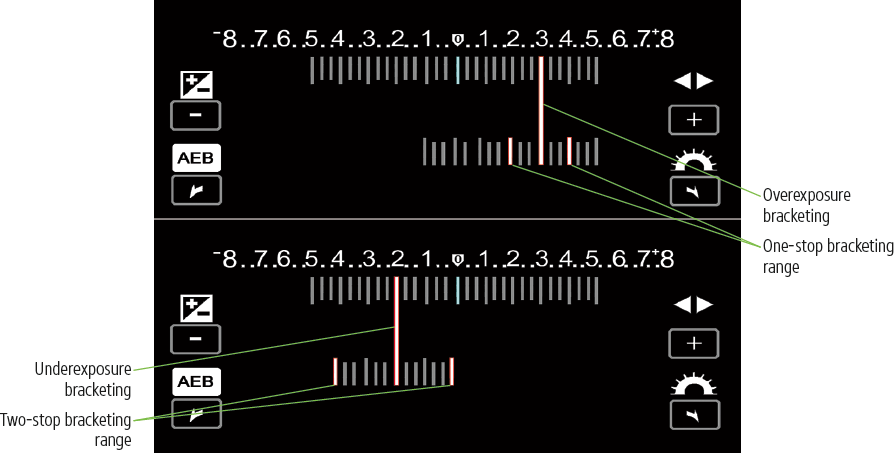

You can choose the size of the jump between each of the bracketed exposures. To do that, you’ll need to visit the Expo. Comp/AEB entry in the Shooting 2 menu. There, you can select from plus/minus 1/3 to 3 full stops in 1/3-stop increments, by rotating the Main Dial. The next section provides instructions for producing a bracketed set.

Using AEB is trickier than it needs to be, but it has been made more flexible than it was with earlier models. With the 90D you can now choose to bracket only overexposures or underexposures—a very useful improvement! Just follow these steps:

- 1. Activate the Expo. Comp./AEB screen. Press the MENU button and navigate to the Shooting 2 menu, where you’ll find the Expo. Comp./AEB option. Choose SET to select this choice.

- 2. Set the bracket range. Rotate the Main Dial to spread out or contract the three bars to include the desired range you want to cover. For example, in Figure 4.15 (top), the red highlighted bars are separated from the center bar by a full f/stop, so the bracketing will produce one image at one stop less than the zero point (the large center bar), one at the zero point, and one at one stop more than that. Figure 4.15 (bottom) shows the bars more widely separated, for a bracketed set two stops under and two stops over the midpoint.

- 3. Adjust zero point. By default, the bracketing is zeroed around the center of the scale, which represents the correct exposure as metered by the 90D. But you might want to have your three bracketed shots all biased toward overexposure or underexposure. Perhaps you feel that the metered exposure will be too dark or too light, and you want the bracketed shots to lean in the other direction. Rotate the QCD or use the left/right multi-controller buttons to move the bracket spread toward one end of the scale or the other. Figure 4.15 (top) shows the bracketing biased toward overexposure, while in 4.15 (bottom), the zero point is clustered around underexposure. (Actually, the exposure bar at left will be four stops under the metered exposure, the center bar two stops under, and the right bar at the metered value.)

Figure 4.15 Use the left/right multi-controller buttons to bias the bracketing toward more or less exposure, and the Main Dial to set the bracket range.

NON-BRACKETING IS EXPOSURE COMPENSATION

When the three bracket indicators aren’t separated, using the left/right multi-controller buttons simply, in effect, adds or subtracts exposure compensation. You’ll be shooting a “bracketed” set of one picture, with the zero point placed at the portion of the scale you indicated. Until you rotate the Main Dial to separate the three bracket indicators by at least one indicator, this screen just supplies EV adjustment. Also keep in mind that the increments shown will be either 1/3 stop or 1/2 stop, depending on how you’ve set C.Fn I-1.

- 4. Confirm your choice. Choose SET to enter the settings.

- 5. Take your three photos. You can use Single shooting mode to take the trio of pictures yourself, use the self-timer (which will expose all three pictures after the delay), or switch to Continuous shooting mode to take the three pictures in a burst.

- 6. Monitor your shots. As the images are captured, three indicators will appear on the exposure scale in the viewfinder, with one of them flashing for each bracketed photo, showing when the base exposure, underexposure, and overexposure are taken.

- 7. Turn bracketing off when done. If you haven’t specified automatic bracket cancel, as described above, bracketing remains in effect when the set is taken so you can continue shooting bracketed exposures until you use the electronic flash, turn off the camera, or return to the menu to cancel bracketing.

NOTEAEB is disabled when you’re using Multi Shot Noise Reduction, taking long time exposures with the Bulb setting, or have enabled the Auto Lighting Optimizer in the Shooting 2 menu (in which case the optimizer will probably override and nullify bracketing).

Working with HDR

High dynamic range (HDR) photography is quite the rage these days, and entire books have been written on the subject. It’s not really a new technique—film photographers have been combining multiple exposures for ages to produce a single image of, say, an interior room while maintaining detail in the scene visible through the windows.

Suppose you wanted to photograph a dimly lit room that had a bright window showing an outdoors scene. Proper exposure for the room might be on the order of 1/60th second at f/2.8 at ISO 200, while the outdoors scene probably would require f/11 at 1/400th second. That’s almost a 7 EV step difference (approximately 7 f/stops) and well beyond the dynamic range of any digital camera, including the Canon 90D.

Until camera sensors gain much higher dynamic ranges (which may not be as far into the distant future as we think), special tricks like Highlight Tone Priority and HDR photography will remain basic tools. With the Canon 90D, you can create in-camera HDR exposures, or shoot HDR the old-fashioned way—with separate bracketed exposures that are later combined in a tool like Photomatix, the Nik HDR Efex Pro 2 (part of DxO’s Nik Collection), or Adobe’s Merge to HDR Pro image-editing feature. I’m going to show you how to use both methods.

Using HDR Mode

Here are some tips for using this built-in feature, found in the Shooting 3 menu:

- Use a tripod if possible. Because there may be some camera movement between the continuous shots, you’ll get better results if you mount the 90D on a tripod.

- Moving objects may produce ghosts. In this case, there may be some subject motion between shots, producing “ghost” effects.

- Misalignment. If you don’t use a tripod, when Auto Image Align is activated, this mode does a good job of realigning your multiple images when they are merged. However, it can’t do a perfect job, particularly with repetitive patterns that are difficult for the camera’s “brains” to sort out. Some misalignment is possible.

- Shutter speeds vary. The camera brackets by adjusting the shutter speed within the increment range selected, even if you’re using Tv or M modes and have specified a shutter speed.

- Unwanted cropping. Because the processor needs to be able to shift each individual image slightly in any (or all) of four directions in Auto Align mode (described next), it needs to crop the image slightly to trim out any non-image areas that result. Your final image will be slightly smaller than one shot in other modes.

- Weird colors. Some types of lighting, including fluorescent and LED illumination, “cycle” many times a second, and colors can vary between shots. You may not even notice this when single shooting, but it becomes more obvious when using any continuous shooting mode, including HDR mode. The combined images may have strange color effects.

- Can’t use any RAW mode, or ISOs higher than 25600. Your image will be recorded as a Large JPEG only, and HDR is disabled when you’re using ISO expansion to enable sensitivity settings higher than 12800. While you can use HDR mode if Auto Lighting Optimizer has been enabled, the camera will disable it while shooting your HDR images, then re-enable it when you turn HDR mode off.

- The process takes time. Forget about firing off a large number of HDR shots in a row. After the 90D captures its three images, it takes a few seconds to process them and save your final image. Be patient.

Access HDR mode from the Shooting 4 menu, and you’ll be taken to a menu with four entries:

- Adjust Dynamic Range. There are five choices in this entry. Select Disable HDR to turn HDR completely off. The others select the number of stops of dynamic range improvement the HDR feature will provide. Choose Auto to allow the 90D to examine your scene and select an appropriate EV range. As you gain experience you might want to select the range yourself, in order to achieve a particular look. You can choose plus/minus 1, 2, or 3 EV.

- Effect. You can select Natural (the default), Art Standard, Art Vivid, Art Bold, and Art Embossed. These choices overcome one of the key shortcomings found in other cameras’ built-in HDR features: the ability to select exactly how you want the HDR effect applied. The differences don’t show up well on the printed page, so I urge you to experiment with these options with typical subject matter so you can decide on your own which is most suitable for your particular subjects. My recommendation: I strongly prefer Natural, because for the type of photography I do, if you can tell that I used HDR, I’ve overprocessed my image. If you want a more drastic effect, however, go for it.

- Continuous HDR. Choose 1 Shot Only if you plan to take just a single HDR exposure and want the feature disabled automatically thereafter, or Every Shot to continue using HDR mode for all subsequent exposures until you turn it off.

- Auto Image Align. HDR images are ideally produced with the camera on a tripod, in order to reduce the ghosting effects from a series of pictures that each aren’t perfectly aligned with the other. You can choose Enable to have the camera attempt to align all three HDR exposures or select Disable when using a tripod. The success of the automatic alignment will vary, depending on the shutter speed used (higher is better), and the amount of camera movement (less is better!).

HDR Backlight Control

The 90D’s in-camera HDR Backlight Control feature, available as a Special Scene option when the Mode Dial is in the SCN position, is simple, not particularly flexible, but still surprisingly effective in creating high dynamic range images. It’s also remarkably easy to use. It combines three images to create a single HDR photograph, and it’s not as effective as the HDR mode feature already discussed, or as powerful as the manual HDR method I’ll describe in the section after this one.

Figure 4.16 shows you a typical situation in which you might want to use this setting. When the exposure is set for the interior of the cathedral, the beautiful backlit stained-glass windows (top left) are washed out and have no detail. When the exposure is adjusted to produce detail in the glass panes (top right), the rest of the cathedral goes dark. The quickie solution is to use the 90D’s HDR Backlight Control. It captures three consecutive images, including similar to the two at top, plus a third with an exposure between the two, and then merges them to preserve both highlight and shadow detail, as you can see at bottom in the figure, which has a much fuller range of tones.

Here are some tips for using this feature (these also apply to the Handheld Night Scene mode, which also merges multiple shots to create a single improved image):

- Use a tripod if possible. Because there may be some camera movement between the continuous shots, you’ll get better results if you mount the 90D on a tripod.

- Moving objects may produce ghosts. In this case, there may be some subject motion between shots, producing “ghost” effects.

Figure 4.16 Exposing for the interior produces overexposed backlit stained-glass windows (top left), while exposing for the windows captures a murky interior (top right). The 90D’s HDR Backlight Control mode captures a full range of tones (bottom).

- Misalignment. If you don’t use a tripod, this scene mode does a good job of realigning your multiple images when they are merged. However, it can’t do a perfect job, particularly with repetitive patterns that are difficult for the camera’s “brains” to sort out. Some misalignment is possible.

- Unwanted cropping. Because the processor needs to be able to shift each individual image slightly in any (or all) of four directions, it needs to crop the image slightly to trim out any non-image areas that result. Your final image will be slightly smaller than one shot in other modes.

- Can’t use any RAW or RAW+ JPEG setting. Your image will be recorded as a Large JPEG only.

- The process takes time. Forget about firing off a large number of HDR Backlight Control shots in a row. The camera display of the number of exposures taken will blink while the images are processing. After the 90D captures its three images, it takes a few seconds to process them and save your final image. Be patient.

Bracketing and Merge to HDR

Creating HDR images manually is not difficult. You simply shoot individual images either by manually bracketing or using the camera’s auto bracketing modes, described earlier in this chapter.