You can happily spend your entire shooting career using the techniques and features already explained in this book. Great exposures, sharp pictures, and creative compositions are all you really need to produce great shot after great shot. But those with enough interest in getting the most out of their Canon EOS 90D will be interested in going beyond those basics to explore some of the more advanced techniques and capabilities of the camera. So, in this chapter, I’m going to offer longer discussions of some of the more advanced techniques and capabilities that I like to put to work.

Continuous Shooting

Even a seasoned action photographer can miss the decisive instant when a crucial block is made, or a baseball superstar’s bat shatters and pieces of cork fly out. Kids or grandchildren at play can be difficult to photograph as they gleefully race around. And capturing a rambunctious pet can be challenging. Continuous shooting simplifies taking a series of pictures, either to ensure that one has more or less the exact moment you want to capture or to capture a sequence that is interesting as a collection of successive images. Fortunately, digital cameras have reusable “film,” so if you waste a few dozen shots on non-decisive moments, you can erase them and shoot more. Save only the best shots, like the series shown in Figure 13.1.

Continuous shooting is available in any Creative Zone or Basic Zone mode (and, in fact, is mandatory in Sports mode). To use the 90D’s Continuous shooting mode, press the Drive button on top of the camera and use the touch screen, Quick Control Dial, or multi-controller to select one of three Continuous shooting icons. Alternatively, you can press the Q button to pop up the Quick Control screen and use the touch screen or physical controls to specify the drive mode. When you partially depress the shutter button, the viewfinder will display a number representing the maximum number of shots you can take at the current quality settings. (If your battery is low, this figure will be lower.) The three Continuous shooting modes are Continuous High, Continuous Low, and Silent Continuous:

- Continuous High. When you hold down the shutter button, the 90D captures images at up to 10 frames per second with viewfinder shooting. In live view mode, you can capture up to 11 frames per second in One Shot AF mode, and 7.0 fps with Servo AF (as the camera will refocus between each shot).

Figure 13.1 Continuous shooting allows you to capture an entire sequence of exciting moments as they unfold.

The top speeds are achieved when your battery is fully charged, a shutter speed of 1/1000th second or faster is used, and the maximum (largest) aperture of the lens is specified. The frame rate may decrease when using flash, AI Servo or Servo AF focus mode, or when flicker reduction is enabled. Shooting may also slow when the 90D’s internal memory buffer fills, until some shots are transferred to your memory card.

- Continuous Low. At this setting, the camera grabs images at up to 3.0 fps in viewfinder mode and live view modes. If you are using the Panning scene mode, expect up to 5.7 fps in viewfinder shooting and 4.3 fps in live view.

- Silent Continuous. This mode is available only with viewfinder shooting and produces slightly quieter noises from shutter and mirror movement at up to 3 frames per second. With Silent Continuous operation, the mirror swings up more slowly. After each exposure, the mirror and shutter mechanisms will reset at a slower and quieter rate, producing the 3 fps maximum rate. It’s not silent, but it is a bit quieter. Note that the time lag between pressing the shutter button down all the way and the first picture taken may be slightly longer.

As noted above, Continuous shooting can be affected by the speed with which your 90D is able to focus. Lenses that inherently focus more slowly (see Chapter 6 for information on the various types of autofocus motors built into Canon lenses), and scenes that are poorly lit can also affect the frame rate, because such conditions also may slow down AF speed.

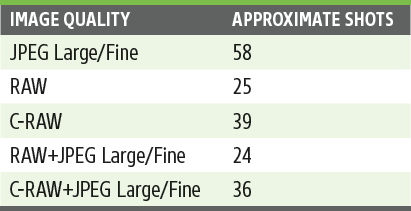

Table 13.1 shows the number of shots you can expect at the fastest frame rate before the buffer fills and capture begins to slow down. To increase these numbers, reduce the image-quality setting by switching to JPEG only (from JPEG+RAW), to a lower JPEG quality setting, or by reducing the 90D’s resolution from L to M or S.

TABLE 13.1 Shots until Buffer Fills

The reason the size of your bursts is limited by the buffer is that continuous images are first shuttled into the 90D’s internal memory, then doled out to the memory card as quickly as they can be written to the card. Technically, the 90D takes the RAW data received from the digital image processor and converts it to the output format you’ve selected—either JPG or CR3 (RAW), or both—and deposits it in the buffer ready to store on the card.

When the buffer fills, you can’t take any more continuous shots (a buSY indicator appears in the viewfinder) until the 90D has written some of them to the card, making more room in the buffer. (You should keep in mind that faster memory cards write images more quickly, freeing up buffer space faster.)

BURSTS NOT JUST FOR ACTION

I often use Continuous shooting mode even when I’m not busy shooting action. As I’ve mentioned before, bursts make sense when you’re shooting HDR or bracketing. But here’s a technique you might not have thought of—continuous shooting can give you sharper images!

When I’m photographing concerts, I most frequently use my 70-200mm f/2.8 IS zoom, handheld, with image stabilization turned on, and using the highest continuous frame rate at my disposal. I enjoy greater mobility by not using a monopod (and a tripod would be even more of a ball-and-chain, even if not forbidden by the venue). I’m generally shooting at around 1/180th second, which is usually fast enough to eliminate blur from the performers’ motion. IS has no effect on stopping their movement, of course, and it does a fairly good job of eliminating camera/photographer shake. However, I invariably find that if I shoot in Continuous, one of the middle frames in a sequence will be sharpest. Even the most seasoned photographer will add a little bump to the camera when they squeeze (not stab) the shutter release.

More Exposure Options

In Chapter 4, you learned techniques for getting the right exposure, but I haven’t explained all your exposure options just yet. You’ll want to know about the kind of exposure settings that are available to you with the Canon EOS 90D. There are options that let you control when the exposure is made, or even how to make an exposure that’s out of the ordinary in terms of length (time or bulb exposures). The sections that follow explain your camera’s special exposure features, and even discuss a few it does not have (and why it doesn’t).

A Tiny Slice of Time

Exposures that seem impossibly brief can reveal a world we didn’t know existed. In the 1930s, Dr. Harold Edgerton, a professor of electrical engineering at MIT, pioneered high-speed photography using a repeating electronic flash unit he patented called the stroboscope. As the inventor of the electronic flash, he popularized its use to freeze objects in motion, and you’ve probably seen his photographs of bullets piercing balloons and drops of milk forming a coronet-shaped splash.

Electronic flash freezes action by virtue of its extremely short duration—as brief as 1/50000th second or less. Although the EOS 90D’s built-in flash unit can give you these ultra-quick glimpses of moving subjects, an external flash, such as one of the Canon Speedlites, offers even more versatility. You can read more about using electronic flash to stop action in Chapter 11.

Of course, the 90D is fully capable of immobilizing all but the fastest movement using only its shutter speeds, which range all the way up to 1/8000th second. Indeed, you’ll rarely have need for such a brief shutter speed in ordinary shooting. If you wanted to use an aperture of f/2.8 at ISO 100 outdoors in bright sunlight, for some reason, a shutter speed of 1/4000th second would more than do the job. You’d need a faster shutter speed only if you moved the ISO setting to a higher sensitivity (but why would you do that?). Under less than full sunlight, 1/4000th second is more than fast enough for any conditions you’re likely to encounter, so you’re unlikely to ever need the top shutter speed built into your camera.

Most sports action can be frozen at 1/2000th second or slower, and for many sports a slower shutter speed is actually preferable—for example, to allow the wheels of a racing automobile or motorcycle, or the propeller on a classic aircraft to blur realistically.

But if you want to do some exotic action-freezing photography without resorting to electronic flash, the 90D’s top shutter speed is at your disposal. Here are some things to think about when exploring this type of high-speed photography:

- You’ll need a lot of light. High shutter speeds cut very fine slices of time and sharply reduce the amount of illumination that reaches your sensor. To use 1/4000th second at an aperture of f/6.3, you’d need an ISO setting of 800—even in full daylight. To use an f/stop smaller than f/6.3 or an ISO setting lower than 800, you’d need more light than full daylight provides. (That’s why electronic flash units work so well for high-speed photography when used as the sole illumination; they provide both the effect of a brief shutter speed and the high levels of illumination needed.)

- Don’t combine high shutter speeds with electronic flash. You might be tempted to use an electronic flash with a high shutter speed. Perhaps you want to stop some action in daylight with a brief shutter speed and use electronic flash only as supplemental illumination to fill in the shadows. Unfortunately, under most conditions you can’t use flash in subdued illumination with your 90D at any shutter speed faster than 1/250th second. That’s the fastest speed at which the camera’s focal plane shutter is fully open: at shorter speeds, the “slit” described above comes into play, so that the flash will expose only the small portion of the sensor exposed by the slit during its duration. (Check out “Avoiding Sync Speed Problems” in Chapter 11 if you want to see how you can use shutter speeds shorter than 1/250th second with certain Canon Speedlites, albeit at much-reduced effective power levels.)

Working with Short Exposures

You can have a lot of fun exploring the kinds of pictures you can take using very brief exposure times, whether you decide to take advantage of the action-stopping capabilities of your built-in or external electronic flash or work with the Canon EOS 90D’s faster shutter speeds. Here are a few ideas to get you started:

- Take revealing images. Fast shutter speeds can help you reveal the real subject behind the façade, by freezing constant motion to capture an enlightening moment in time. Legendary fashion/portrait photographer Philippe Halsman used leaping photos of famous people, such as the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, Richard Nixon, and Salvador Dali to illuminate their real selves. Halsman said, “When you ask a person to jump, his attention is mostly directed toward the act of jumping and the mask falls so that the real person appears.” Try some high-speed portraits of people you know in motion to see how they appear when concentrating on something other than the portrait. (See Figure 13.2.)

- Create unreal images. High-speed photography can also produce photographs that show your subjects in ways that are quite unreal. A helicopter in mid-air with its rotors frozen makes for an unusual picture. Figure 13.3 shows a pair of pictures. At top, a shutter speed of 1/1000th second virtually stopped the rotation of the chopper’s rotors, while the bottom image, shot at 1/200th second, provides a more realistic view of the blurry blades as they appeared to the eye.

- Capture unseen perspectives. Some things are never seen in real life, except when viewed in a stop-action photograph. MIT scientist Dr. Harold Edgerton’s balloon bursts were only a starting point. Freeze a hummingbird in flight for a view of wings that never seem to stop. Or capture the splashes as liquid falls into a bowl, as shown in Figure 13.4. No electronic flash was required for this image (and wouldn’t have illuminated the water in the bowl as evenly). Instead, a clutch of high-intensity lamps and an ISO setting of 1600 allowed the 90D to capture this image at 1/2000th second.

Figure 13.2 When your subjects leap, the real person inside emerges.

Figure 13.3 Top: the chopper’s blades are frozen at 1/1000th second; bottom: a more realistic blurry rendition at 1/200th second shutter speed.

Figure 13.4 A large amount of artificial illumination and an ISO 1600 sensitivity setting allowed capturing this shot at 1/2000th second without use of an electronic flash.

- Vanquish camera shake and gain new angles. Here’s an idea that’s so obvious it isn’t always explored to its fullest extent. A high-enough shutter speed can free you from the tyranny of a tripod, making it easier to capture new angles, or to shoot quickly while moving around, especially with longer lenses. I tend to use a monopod or tripod for almost everything when I’m not using an image-stabilized lens, and I end up missing some shots because of a reluctance to adjust my camera support to get a higher, lower, or different angle. If you have enough light and can use an f/stop wide enough to permit a high shutter speed, you’ll find a new freedom to choose your shots. I have a favored 170mm-500mm lens that I use for sports and wildlife photography, almost invariably with a tripod, as I don’t find the “reciprocal of the focal length” rule particularly helpful in most cases. (I would not handhold this hefty lens at its 500mm setting with a 1/500th second shutter speed under most circumstances.) However, at 1/2000th second or faster, and with a sufficiently high ISO setting (I recommend ISO 800 to 1600) to allow such a speed, it’s entirely possible for a steady hand to use this lens without a tripod or monopod’s extra support, and I’ve found that my whole approach to shooting animals and other elusive subjects changes in high-speed mode. Selective focus allows dramatically isolating my prey wide open at f/6.3, too.

Long Exposures

Longer exposures are a doorway into another world, showing us how even familiar scenes can look much different when photographed over periods measured in seconds. At night, long exposures produce streaks of light from moving, illuminated subjects like automobiles or amusement park rides. Extra-long exposures of seemingly pitch-dark subjects can reveal interesting views using light levels barely bright enough to see by. At any time of day, including daytime (in which case you’ll often need the help of neutral-density filters, which reduce the amount of light passing through the lens, to make the long exposure practical), long exposures can cause moving objects to vanish entirely, because they don’t remain stationary long enough to register in a photograph.

Three Ways to Take Long Exposures

There are three common types of lengthy exposures: timed exposures, bulb exposures, and bulb/time exposures. Because of the length of the exposure, all of the following techniques should be used with a tripod to hold the camera steady.

- Timed exposures. These are long exposures from 1 second to 30 seconds, measured by the camera itself. To take a picture in this range, simply use Manual or Tv modes and use the Main Dial to set the shutter speed to the length of time you want, choosing from preset speeds of 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 6.0, 8.0, 10.0, 15.0, 20.0, or 30.0 seconds (if you’ve specified 1/2-stop increments for exposure adjustments), or 1.0, 1.3, 1.6, 2.0, 2.5, 3.2, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0, 8.0, 10.0, 13.0, 15.0, 20.0, 25.0, and 30.0 seconds (if you’re using 1/3-stop increments). The advantage of timed exposures is that the camera does all the calculating for you. There’s no need for a stopwatch. If you review your image on the LCD and decide to try again with the exposure doubled or halved, you can dial in the correct exposure with precision. The disadvantage of timed exposures is that you can’t take a photo for longer than 30 seconds. For longer exposures, you’ll need to use the Bulb or Bulb Timer options described next.

- Bulb exposures. This type of exposure is so-called because in the olden days the photographer squeezed and held an air bulb attached to a tube that provided the force necessary to keep the shutter open. Traditionally, a bulb exposure is one that lasts as long as the shutter release button is pressed; when you release the button, the exposure ends. To make a bulb exposure with the 90D, rotate the Mode Dial to the B position. Then, press the shutter to start the exposure, and release it to close the shutter. The elapsed time appears on the monochrome top-panel LCD. You can also shoot bulb exposures with the optional Remote Switch RS-60E3 or Remote Controller RC-6.

- Bulb Timer. This is a setting found on some cameras, including the 90D, to produce longer exposures. Some cameras call the feature time exposure, but that nomenclature is easily confused with ordinary timed exposures. To use this facility with the 90D, set the Mode Dial to B. Then access the Bulb Timer entry in the Shooting 5 menu and choose SET. In the screen that appears, highlight Enable, and then press the INFO. button. You can then select an exposure time up to 99 hours, 59 minutes, and 59 seconds. A TIMER warning will be displayed on the top-panel LCD. Press the shutter button down to start the exposure, which will end automatically when the set time has elapsed. The elapsed time is shown on the monochrome LCD. The Bulb Timer setting will remain until you Disable it in the Shooting 5 menu, or power down the camera.

Note that hours-long exposures aren’t practical. Long before you reach 99 hours the 90D’s battery will be depleted, your image will likely be overexposed, the sensor may overheat, or your final image will suffer from either excessive conventional or amp noise, described next.

WATCH OUT FOR AMP NOISE

When exposures extend past 30 seconds into the realm of several minutes—or more—all digital cameras are theoretically susceptible to a phenomenon called amp noise, which manifests itself as a purplish glow, often around the edges of an image, creating an aurora borealis–style ghost effect. Amp noise happens when the sensor heats up during a long exposure, and some cameras fall victim more readily than others. The 90D resists this phenomenon better than most dSLRs, but you should be aware it exists, even if you’d need to use an uncommon exposure (on the order of 30 minutes or so) to create the effect with your camera.

Working with Long Exposures

Because the 90D produces such good images at longer exposures, and there are so many creative things you can do with long-exposure techniques, you’ll want to do some experimenting. Get yourself a tripod or another firm support and take some test shots with long exposure noise reduction both enabled and disabled using the entry in the Shooting 4 menu, as explained in Chapter 8 (to see whether you prefer low noise or high detail) and get started.

- Make people invisible. One very cool thing about long exposures is that objects that move rapidly enough won’t register at all in a photograph, while the subjects that remain stationary are portrayed in the normal way. That makes it easy to produce people-free landscape photos and architectural photos at night or, even, in full daylight if you use a neutral-density filter (or two or three) to allow an exposure of at least a few seconds. At ISO 100, f/22, and a pair of 8X (three-stop) neutral-density filters, you can use exposures of nearly two seconds; overcast days and/or more neutral-density filtration would work even better if daylight people-vanishing is your goal. They’ll have to be walking very briskly and across the field of view (rather than directly toward the camera) for this to work. At night, it’s much easier to achieve this effect with the 20- to 30-second exposures that are possible, as you can see in Figure 13.5.

- Create streaks. If you aren’t shooting for total invisibility, long exposures with the camera on a tripod or monopod can produce some interesting streaky effects, as you can see in Figure 13.6. You don’t need to limit yourself to indoor photography, however. Even a single 8X ND (neutral-density) filter will let you shoot at f/22 and 1/6th second in full daylight at ISO 100.

- Produce light trails. At night, car headlights and taillights and other moving sources of illumination can generate interesting light trails. Your camera doesn’t even need to be mounted on a tripod; handholding the 90D for longer exposures adds movement and patterns to your trails. If you’re shooting fireworks, a longer exposure of several seconds may allow you to combine several bursts into one picture, as shown in Figure 13.7, which was shot with a tripod-mounted camera.

Figure 13.5 This alleyway is thronged with people, as you can see in this two-second exposure using only the available illumination (left). With the camera still on a tripod, a 30-second exposure rendered the passersby almost invisible (right).

Figure 13.6 These dancers produced a swirl of movement during the 1/8th-second exposure.

Figure 13.7 A long exposure and a tripod allow capturing several bursts of fireworks in one image.

- Blur waterfalls, etc. You’ll find that waterfalls and other sources of moving liquid produce a special type of long exposure blur, because the water merges into a fantasy-like veil that looks different at different exposure times, and with different waterfalls. Cascades with turbulent flow produce a rougher look at a given longer exposure than falls that flow smoothly. Although blurred waterfalls have become almost a cliché, there are still plenty of variations for a creative photographer to explore, as you can see in Figure 13.8.

- Show total darkness in new ways. Even on the darkest nights, there is enough starlight or glow from distant illumination sources to see by, and, if you use a long exposure, there is enough light to take a picture, too. Figure 13.9 shows San Juan, Puerto Rico late at night.

Figure 13.8 A 1/4-second exposure blurred the falling water.

Figure 13.9 A 20-second exposure revealed this view of San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Delayed Exposures

Sometimes it’s desirable to have a delay of some sort before a picture is taken. Perhaps you’d like to get in the picture yourself and would appreciate it if the camera waited 10 seconds after you press the shutter release to take the picture. Maybe you want to give a tripod-mounted camera time to settle down and damp any residual vibration after the release is pressed to improve sharpness for an exposure with a relatively slow shutter speed. It’s possible you want to explore the world of time-lapse photography. The next sections present your delayed exposure options.

Self-Timer

The 90D has a built-in self-timer with 10-second and 2-second delays. Activate the timer by pressing the Drive button and press the left directional buttons until the drive modes appear on the LCD status panel. Press the shutter release button halfway to lock in focus on your subjects (if you’re taking a self-portrait, focus on an object at a similar distance and use focus lock). When you’re ready to take the photo, continue pressing the shutter release the rest of the way. The lamp on the front of the camera will blink slowly for eight seconds (when using the 10-second timer) and the beeper will chirp (if you haven’t disabled it in the Shooting menu, as described in Chapter 7). During the final two seconds, the beeper sounds more rapidly, and the lamp remains on until the picture is taken.

You can also use the Self-timer (Continuous) option from the Drive mode menu. Rotate the QCD to specify from 2 to 9 shots taken at the end of the self-timer delay. I use this when shooting self-portraits and group shots, as it offers the opportunity to change expressions between shutter clicks and improve chances of capturing everyone in a group with their eyes open.

Another way to use the self-timer is with the mirror lockup feature (which can be enabled using the entry in the Shooting 5 menu, as explained in Chapter 7). This is something you might want to do if you’re shooting close-ups, landscapes, or other types of pictures using the self-timer, to trip the shutter in the most vibration-free way possible. Forget to bring along your tripod, but still want to take a close-up picture with a precise focus setting? Set your digital camera to the self-timer function, then put the camera on any reasonably steady support, such as a fence post or a rock. When you’re ready to take the picture, press the shutter release. The camera might teeter back and forth for a second or two, but it will settle back to its original position before the self-timer activates the shutter. The self-timer remains active until you turn it off—even if you power down the 90D—so remember to turn it off when finished.

Time-Lapse Movies

Who hasn’t marveled at a time-lapse movie of a flower opening, a series of shots of the moon marching across the sky, or one of those extreme interval photography picture sets showing something that takes a very, very long time, such as a building under construction.

You probably won’t be shooting such construction shots, unless you have a spare 90D you don’t need for a few months (or are willing to go through the rigmarole of figuring out how to set up your camera in precisely the same position using the same lens settings to shoot a series of pictures at intervals). However, other kinds of time-lapse photography are entirely within reach.

The 90D has built-in features that allow you to shoot time-lapse movies easily and create a set of still photographs taken at intervals you specify. Before I explain how to use these features, here are a few things to keep in mind:

- Use AC power. If you’re shooting a long sequence, consider connecting your camera to an AC adapter, as leaving the 90D on for long periods of time will rapidly deplete the battery. The optional Canon DC Coupler DR-E6 and AC Adapter AC-6N are perfect for this application. While shooting time-lapse movies, auto power off will not take place.

- Make sure you have enough storage space. Unless your memory card has enough capacity to hold all the images you’ll be taking, you might want to change to a higher compression rate or reduced resolution to maximize the image count.

- Use a tripod. Hand-held time-lapse movies are stomach-churning experiences.

- Protect your camera. If your camera will be set up for an extended period (longer than an hour or two), make sure it’s protected from weather, earthquakes, animals, young children, innocent bystanders, and theft.

- Vary intervals. Experiment with different time intervals. You don’t want to take pictures too often or less often than necessary to capture the changes you hope to image in your movies or still series.

The 90D’s time-lapse movie facility is actually a still photography mode that shoots images at intervals you specify, and then stitches them together automatically to create an MP4-format movie in both 4K and Full HD resolutions at a playback rate of 30/25 fps. Time-lapse movies are silent. To create a time-lapse movie, just follow these steps:

- 1. Set Mode Dial. Rotate the Mode Dial to the Scene Intelligent Auto, Program, Shutter-priority, Aperture-priority, or Bulb positions.

- 2. Set the Live View/Movie switch to the Movie position. Even though time-lapse clips are a series of stills, you must be in Movie mode to access the feature. Even though individual images are still photographs, no stills are stored; the 90D converts them to a movie file even if you take only one shot in time-lapse mode.

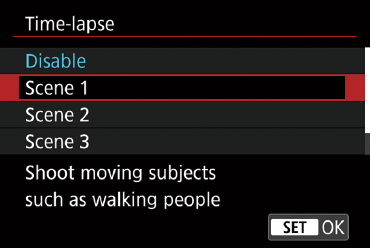

- 3. Navigate to the Shooting 1 (Movie) menu. Select Time-Lapse Movie and choose SET. (See Figure 13.10, left.)

- 4. Enable Time-Lapse. Highlight the Time-Lapse entry (see Figure 13.10, right) and choose SET. The screen shown in Figure 13.11 appears.

Figure 13.10 Choose Time-lapse Movie (left); the Time-lapse Movie menu.

Figure 13.11 Select a Scene or Custom parameters.

- 5. Select Scene. Choose the type of time-lapse movie you want to capture:

- Scene 1: Moving subjects such as walking people. The camera sets an interval of 3 seconds between shots, and a total of 300 shots. When played back at 30 fps, your time-lapse movie will last 30 seconds.

- Scene 2: Subjects that are moving, but which change relatively slowly. The march of clouds across the sky is a good example. The camera specifies a longer 5-second interval between exposures, and captures a total of 240 frames, producing a 40-second movie.

- Scene 3. Subjects that change very slowly. A longer 15-second interval between shots and a total of 240 shots will be used to capture a 2-minute long video clip.

- Custom. You’ll need to scroll down the list to access the Custom option. Choose your own number of shots and interval between them. Intervals as long as 60 minutes between shots and as many as 3,600 frames can be captured, producing a movie that spans 150 days—but still will play back in two minutes. (3,600 frames divided by the playback speed of 30 fps will always equal 120 seconds/two minutes.)

The custom option gives you the most flexibility. Shooting 3,600 frames at 10-second intervals would cover the motion of a flower blooming over the course of 10 hours. Changing to one shot each 12 minutes would capture 30 days of progress at a construction site.

- 6. Exit Time-lapse Scene/Custom screen. When you’ve selected Scene 1–3 or Custom, choose SET. You’ll be returned to the main screen shown earlier in Figure 13.10, left. The default settings for the Scene you’ve select will be displayed. If they are satisfactory, skip to Step 8. If you want to change the Scene settings or specify a Custom set, continue with Step 7.

- 7. Adjust Interval/Shots. Highlight Interval/Shots and choose SET.

- Scenes 1–3. You can change the default settings for Scenes 1–3 within a restricted range suitable for each scene type. Highlight Interval and No. of Shots in turn, choose SET, and use the left/right controls to tweak each of those in the allowable range. Press INFO. to return to the default set for that scene. Choose SET to confirm and exit.

- Custom. If you’ve selected Custom, you have full control over Interval and Number of Shots. The Interval between shots can range from 2 seconds to 60 minutes. The total number of shots can range from 2 shots to 3,600 shots. Choose SET to confirm each value.

The total time that will be captured and the playback time are displayed at near the bottom of the screen. (See Figure 13.12.) Highlight OK and choose SET to confirm and exit.

Note: If the Playback Time is displayed in red, that particular combination of Interval/Shots is not available with your current memory card. For example, if the card does not have enough free space or the card is not formatted using exFAT and the movie file is larger than 4GB, capture will stop when the movie reaches that size.

- 8. Choose movie recording size. Choose Movie Recording Size. Time-lapse movies can be captured in 4K (3840 × 2160 pixels) at 30 fps for NTSC (25 fps for PAL); or Full HD (1920 × 1080 pixels) at the same frame rates. (I explained NTSC and PAL formats in Chapter 10.)

Figure 13.12 Make individual settings.

- 9. Set Auto Exposure. You can choose Fixed 1st Frame or Each Frame. The difference:

- Fixed 1st Frame. The exposure is set automatically for the first frame, and then that exposure is used for the rest of the time-lapse sequence. You might want to use this option when shooting under changing lighting conditions when you want the exposure to reflect that variation. A sunset sequence might appear more dramatic if the scene gradually gets darker and darker as the sun drops below the horizon.

- Each Frame. Use this option to compensate for changing lighting conditions during capture. Outdoors, for example, clouds may cloak the sun’s illumination. Changing the exposure for each frame will keep the brightness the same for the entire sequence. It’s up to you to decide whether that’s the “look” you want for your time-lapse movie. A time-lapse showing a flower blooming might look best with even illumination as the sunlight changes throughout the day.

- 10. Screen Auto Off. Choose Disable, and the screen will not turn off during shooting for up to 30 minutes. That will let you monitor the shooting to make sure your movie is framed and exposed correctly. After 30 minutes have elapsed, the screen will turn off, saving battery power. Choose Enable, and the screen turns off automatically 10 seconds after shooting has started. Use this option when you don’t need to monitor shooting. Note: If you do want to view the screen during time-lapse capture, you can turn it on/off by pressing the INFO. button. In all cases, the screen turns off while a frame is being exposed.

- 11. Set Beeper. Scroll down to access the Beep as Image Taken option. Choose Enable, and the 90D’s beeper will sound as each frame is captured. Select Disable to keep it silent.

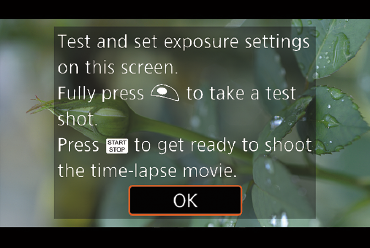

- 12. Check your settings. When you’ve finished setting your options, review them. Press MENU to confirm. Press MENU again and the screen shown in Figure 13.13 appears. You can take a test shot in JPEG format by pressing the shutter button down all the way.

- 13. Press START/STOP button. The 90D will be ready to begin recording your time-lapse movie.

- 14. Capture movie. Press the shutter button all the way to begin capturing your movie. Press it a second time to stop capture.

- 15. Exit Time-lapse. Set Time-lapse to Disable when you want to stop recording time-lapse movies.

Figure 13.13 Test your settings before beginning capture.

Here are some additional tips:

- Cautions. Avoid pointing the camera at a very bright light, zooming the lens, panning the camera, or recording under flickering illumination.

- Your interval cannot be longer than the shutter speed used. For example, you can’t capture one image every two seconds when your shutter speed is four seconds. If the time to record a frame to a memory card exceeds the interval, or if the 90D is unable to capture the next frame for any other reason, that frame will be skipped.

- Disabled functions. While capturing time-lapse movies, shooting and menu functions and playback are disabled, along with Movie Servo AF. You can’t shoot time-lapse movies if digital zoom is enabled, and sound is not recorded. Built-in or external flash and image stabilization are disabled.

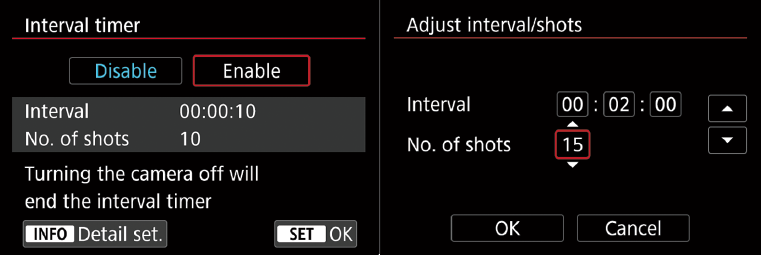

Interval Timer Shooting

The 90D also allows you to shoot a series of still shots at intervals you specify. The function is like time-lapse movie shooting in many respects but must be done in viewfinder still photography mode. Nor can you shoot movies or use Bulb exposures. Here are some other things to consider:

- Interval timing can be combined with other functions. You can use autoexposure and white balance bracketing, shoot multiple exposures, or access HDR mode. I particularly like to shoot multiple exposures combined with interval shots when doing manual HDR work. For example, I’ve set my 90D on a tripod and configured it to shoot bracketed shots of a sunset at intervals, so I ended up with groups of pictures taken over a span of time that I could combine in Photoshop.

- The 90D is smart enough to override auto power-off settings. After powering down, it will turn itself on roughly one minute before the next shot is taken.

- You don’t have to use the menu to disable interval shooting. Just turn the 90D off.

- Use manual focus if you can. If the camera is unable to autofocus, the shot will not be captured.

- Watch your intervals. As with time-lapse movies, the interval between shots cannot be shorter than the shutter speed.

- Flash is okay. But make sure the interval between shots is longer than the flash’s normal recycling time.

Just follow these steps:

- 1. Access Interval Timer. Visit the Shooting 5 menu and choose Interval Timer, the first entry on the screen. Choose SET.

- 2. Enable. Highlight Enable and choose SET. The screen shown at left in Figure 13.14 appears.

- 3. Access settings. Press the INFO. button to produce the Adjust Interval/Shots screen, which is shown in Figure 13.14, right.

Figure 13.14 Enable Interval Timer shooting (left); choose the interval between shots and number of shots (right).

- 4. Choose an interval between exposures, in hours, minutes, and seconds, from 00:00:01 to 99:59:59.

- 5. Specify number of shots. Choose from 01 to 99, or you can select Unlimited (00) and the camera will continue to capture stills until you stop the timer, the memory card fills, or the battery runs out of juice.

- 6. Confirm. Highlight OK and choose SET.

- 7. Exit. When finished setting up, press the MENU button to exit.

- 8. Press the shutter release button to begin. The Timer indicator on the top-panel LCD status panel will blink. If the camera powers down automatically, it will turn on again automatically about one minute before the next shot. You can combine interval shooting with autoexposure or white balance bracketing, multiple exposures, and HDR mode.

- 9. Stopping. Turn the power switch to off to cancel the interval timer. Otherwise, once the series is complete, the 90D will cancel interval timer shooting automatically.

Focus Bracketing

As I mentioned in Chapter 10, focus bracketing (also called focus stacking or focus shift shooting) is a great technique that allows combining a series of photos each taken using a different plane of focus, so that they can be combined in an image editor to produce a single image with greatly enhanced depth-of-field. You can use Photoshop or an application that supports depth compositing, such as Canon’s own Digital Photo Professional.

If you are doing macro (close-up) photography of flowers, or other small objects at short distances, the depth-of-field often will be extremely narrow. In some cases, it will be so narrow that it will be impossible to keep the entire subject in focus in one photograph. Although having part of the image out of focus can be a pleasing effect for a portrait of a person, it is likely to be a hindrance when you are trying to make an accurate photographic record of a flower, or small piece of precision equipment. One solution to this problem is focus stacking (which Canon calls “Focus Shift Shooting”), a procedure that can be considered like HDR translated for the world of focus—taking multiple shots with different settings, and, using software as explained below, combining the best parts from each image in order to make a whole that is better than the sum of the parts. Focus stacking requires a non-moving object, so some subjects, such as flowers, are best photographed in a breezeless environment, such as indoors.

With the 90D’s Focus Bracketing feature, the camera takes a series of pictures, adjusting the focus slightly between each image, refocusing from closest to your subject to the farthest point that needs to appear sharp. You end up with a series of up to 300 different images that can be combined using two simple Photoshop commands, which I will describe shortly.

You can visualize how focus stacking works if you examine Figure 13.15, which is cropped versions of three actual frames from one of my own focus shift series. All three used an exposure of 1/30th second at f/5.6 with my EF-S 60mm f/2.8 macro lens. At top is the original exposure, with the lens focused on the nearest domino. The center image shows the 35th exposure in the series, in which the focus bracketing feature had adjusted focus on the last row of dominoes. In between were 33 intermediate-focus shots that I merged in Photoshop to produce the finished image at right. Here are the detailed steps you can take to use Focus Bracketing for your own deep-focus images:

- 1. Set the camera firmly on a solid tripod. A tripod or other equally firm support is essential for this procedure. You don’t want the camera (or the subject) to move at all during the exposures.

- 2. Attach a remote release. You want to be able to trigger the camera without moving it. However, the procedure does pause for a short period of time once you activate it, perhaps giving your tripod/camera time to settle down.

- 3. Attach a lens with an appropriate focus range. Focus Bracketing uses the lens’s built-in autofocus motor, so you cannot use a manual focus lens. At the time I wrote this, the EF-S lenses that were compatible are the EF-S 35mm f/2.8 Macro IS STM, EF-S 60mm f/2.8 Macro USM, and EF-S 18-135 f/3.5-5.6 IS USM. Additional full-frame lenses can be used; you can find an updated list at Canon’s website for your country.

- 4. Make exposure settings. You don’t want the aperture to change during the series, so select Aperture-priority (Av) exposure mode. For best results, choose an aperture in the range f/5.6–f/11. Choose an appropriate ISO sensitivity. The 90D determines the exposure for the series with the first shot and does not change thereafter. Unfortunately, you cannot use electronic flash with focus bracketing.

Note: Even though you’ll be effectively increasing depth-of-field through focus bracketing, you should still avoid the widest apertures of your lens, as they are rarely the sharpest f/stops. By f/5.6, which Canon recommends as the largest to use, lenses produce considerably better results. Shutter speed is not as important, because the camera is on a tripod, but I tend to avoid very slow speeds anyway. You can manually set a slightly higher ISO sensitivity, if needed, to obtain the shutter speed/aperture combination you want to use.

Figure 13.15 Closest focus (top), farthest focus (center), merged image (bottom).

- 5. Set the focus modes. Activate One Shot (single focus) as your focus mode and 1-Point AF as your AF-area mode. The lens switch must be set to Autofocus.

- 6. Set the quality of the images to JPEG Large. Use the Shooting 1 menu to make this adjustment.

- 7. Turn off image stabilization. If you lens has IS, turn it off.

- 8. Set focus point to nearest object. Use the directional buttons to position the red focus box on the subject nearest the camera lens.

- 9. In Live View, access the Focus Bracketing entry. You’ll find it in the Shooting 5 menu. It’s shown at left in Figure 13.16. Select an appropriate setting for each of the following four parameters, using my guidelines:

- Focus Bracketing. Choose Enable.

- Number of Shots. You can choose from 2 to 999 individually refocused shots. The number of images captured will depend on how finely you want to have the 90D change focus between shots (and you’ll combine this with the focus increment (step width) option described next). Seriously, unless you’re attempting some sort of super deep-focus shot over a larger area, you’ll rarely need more than 50 shots, and I used only 35 for the example shown earlier in Figure 13.15.

- Focus increment. You can specify values from 1 (a narrow slice per adjustment) and 10 (a much wider focus change). {See Figure 3.16, right.) Canon does not specify how much each increment changes the focus, for a very good reason: it can’t. Depending on the focal length of your lens and your f/stop, the effective plane of apparent focus may vary from narrow, to very narrow, to super-narrow in macro shooting environments. (If you’re confused, see “Circles of Confusion” in Chapter 5.) You may need some trial-and-error to choose the correct number of shots and focus step width. For example, with 50 shots and a wide focus step, the first 10 may encompass your entire subject and the last 40 may be wasted on completely out-of-focus images. It’s often worthwhile to take a test shot, view a slide show of all your images, and decide whether to increase/decrease the number of shots and/or focus step width.

- Exposure Smoothing. The Focus Bracketing feature uses the same exposure settings for each shot in the series, so I recommend shooting under a steady, constant source of illumination. However, as focus changes the relative aperture size of the lens changes slightly as well. Turn Exposure Smoothing On and allow the 90D to account for the difference of the actual aperture value (what cinematographers call a T-stop) relative to the constant exposure desired.

Figure 13.16 Focus Bracketing Shooting options (left). Choose a focus increment (right).

- 10. Confirm settings and Exit. When satisfied with your settings, press MENU twice to return to the live view image on the LCD screen. Your settings will appear overlaid on the screen.

- 11. Starting Storage Folder. At the lower-right edge of the screen you’ll find a Folder+ icon. Tap it, and a Create Folder screen appears. Highlight OK and tap OK or press SET to create a new folder that will be used to store your sequence. I can’t think of a reason you would not want to do that. This makes it easier to find and differentiate between the first, last, and in-between images of your set.

- 12. Capture images. Focus at the close end of your focus range and then trigger the shutter with your remote (or by pressing the shutter release button). The camera will take pictures continuously and shift the focus plane from the nearest point you specified outward toward infinity, for as many shots as you specified. Shooting ends when your number of shots or the far end of the focal range is reached.

- 13. Combine your images. I’ll describe the steps for that next.

The next step is to process the images you’ve taken in Photoshop (the most popular option) or Digital Photo Pro. I’m going to outline the steps for Photoshop:

- 1. In Photoshop, select File > Scripts > Load Files into Stack. In the dialog box that then appears, navigate on your computer to find the files for the photographs you have taken, and highlight them all.

- 2. At the bottom of the next dialog box that appears, check the box that says, “Attempt to Automatically Align Source Images,” then click OK. The images will load; it may take several minutes for the program to load the images and attempt to arrange them into layers that are aligned based on their content.

- 3. Once the program has finished processing the images, go to the Layers panel and select all the layers. You can do this by clicking on the top layer and then Shift-clicking on the bottom one.

- 4. While the layers are all selected, in Photoshop go to Edit > Auto-Blend Layers. In the dialog box that appears, select the two options, Stack Images and Seamless Tones and Colors, then click OK. The program will process the images, possibly for a considerable length of time.

- 5. If the procedure worked well, the result will be a single image made up of numerous layers that have been processed to produce a sharply focused rendering of your subject. If it did not work well, you may have to take additional images the next time, focusing very carefully on small slices of the subject as you move progressively farther away from the lens.

- 6. You’ll want to flatten the final image before saving it. Given the 30MP resolution of the 90D, the stack of individual shots will easily be more than 2GB, which exceeds the maximum file size of some storage media and/or OS file systems.

Although this procedure can work very well in Photoshop, you also may want to try it with other programs that were developed more specifically for focus stacking and related procedures, such as Helicon Focus (www.heliconsoft.com), PhotoAcute (www.photoacute.com), or CombineZP (http://extreme-macro.co.uk/downloads/).