It’s not an overstatement to say that Canon has built its reputation on its expertise in lenses. Since the company began producing its own lenses for Canon cameras in mid-1947, it has pioneered many innovations, including the world’s first 10X zoom lens, the first lenses to include optical image stabilization, and the first super-telephoto lens to include a built-in tele-extender.

Indeed, it’s not widely known that Canon was one of the very first companies to offer autofocus lenses, even before the EOS system was introduced. The company produced a total of four AF lenses for its FD-mount cameras. Only one, the FD 35-70mm f/4 AF, worked on all Canon FD cameras; the other three (a 50mm f/1.8, a 35-70mm f/3.5-4.5, and a 75-200mm f/4.5) were compatible only with the Canon T80 camera.

Of course, in the ensuing years Canon has also developed even more advanced camera technology, too, combining its proficiency in both optical and digital arenas. Because of the quality of Canon optics, photographers who started out using Canon camera bodies and lenses have tended to hang onto their lenses for many years, even as they upgraded to newer camera bodies with more features. Indeed, many of us have stuck with the Canon brand at least partially because we were able to use our existing kit of lenses with our latest and greatest camera. After all, an enthusiast’s optics collection can easily have cost many times the price of the body itself. Canon has sold more than 140 million EF lenses, and millions more are available from third parties like Tamron, Sigma, and Tokina.

This chapter explains how to select the best lenses for the kinds of photography you want to do.

But Don’t Forget the Crop Factor

From time to time you’ve heard the term crop factor, and you’ve probably also heard the term lens multiplier factor. Both are misleading and inaccurate terms used to describe the same phenomenon: the fact that cameras like the 90D (and most other affordable digital SLRs) provide a field of view that’s smaller and narrower than that produced by certain other (usually much more expensive) cameras, when fitted with exactly the same lens.

Figure 6.1 quite clearly shows the phenomenon at work. The outer rectangle, marked 1X, shows the field of view you might expect with a 28mm lens mounted on a Canon EOS R, a so-called “full-frame” model in the company’s mirrorless camera line. The rectangle marked 1.6X shows the field of view you’d get with that 28mm lens installed on an 90D. It’s easy to see from the illustration that the 1X rendition provides a wider, more expansive view, while the other is, in comparison, cropped.

Figure 6.1 Canon offers digital SLRs with full-frame (1X) and 1.6X crops.

The cropping effect is produced because the sensor of the 90D is smaller than the sensor of the EOS R. The “full-frame” camera has a sensor that’s the size of the standard 35mm film frame, 24mm × 36mm. Your 90D’s sensor does not measure 24mm × 36mm; instead, it specs out at 22.3mm × 14.8mm, or about 62.5 percent of the area of a full-frame sensor, as shown by the yellow box in the figure. You can calculate the relative field of view by dividing the focal length of the lens by .625. Thus, a 100mm lens mounted on a 90D has the same field of view as a 160mm lens on the 5DS. We humans tend to perform multiplication operations in our heads more easily than division, so such field of view comparisons are usually calculated using the reciprocal of .625—1.6—so we can multiply instead (100 / .625 = 160; 100 × 1.6 = 160).

This translation is generally useful only if you’re accustomed to using full-frame cameras (usually of the film variety) and want to know how a familiar lens will perform on a digital camera. I strongly prefer crop factor over lens multiplier, because nothing is being multiplied; a 100mm lens doesn’t “become” a 160mm lens—the depth-of-field and lens aperture remain the same. (I’ll explain more about these later in this chapter.) Only the field of view is cropped. But crop factor isn’t much better, as it implies that the 24mm × 36mm frame is “full” and anything else is “less.” I get e-mails all the time from photographers who point out that they own full-frame cameras with 43.8mm × 32.9mm sensors (like the Hasselblad X1D II 50C medium-format digital model). By their reckoning, the “half-size” sensors found in cameras like the EOS R are “cropped.”

If you’re accustomed to using full-frame film cameras, you might find it helpful to use the crop factor “multiplier” to translate a lens’s real focal length into the full-frame equivalent, even though, as I said, nothing is actually being multiplied. Throughout most of this book, I’ve been using actual focal lengths and not equivalents, except when referring to specific wide-angle or telephoto focal length ranges and their fields of view.

Your First Lens

Back in ancient times (the pre-zoom, pre-autofocus era before the mid-1980s), choosing the first lens for your camera was a no-brainer: you had few or no options. Canon cameras (which used a different lens mount in those days) were sold with a 50mm f/1.4, a 50mm f/1.8, or, if you had deeper pockets, a super-fast 50mm f/1.2 lens. It was also possible to buy a camera as a body alone, which didn’t save much money back when a film SLR like the Canon A-1 sold for a street price of $435—with lens—in 1978. (Thanks to the era of relatively cheap optics, I still own a total of eight 50mm f/1.4 lenses; I picked one up each time I purchased a new or used body.)

Today, your choices are more complicated, and Canon lenses, which now include zoom, autofocus, and, more often than not, built-in image stabilization (IS) features, tend to cost a lot more compared to the price of a camera.

The Canon EOS 90D is frequently purchased with a lens, even now. I purchased my 90D with the Canon EF-S 18-55mm f/3.5-5.6 IS STM autofocus lens (see Figure 6.2). It added only about $150 to the price tag of the body alone and was thus an irresistible bargain. You can also purchase the 90D in a kit with the 18-135mm f/3.5-5.6 IS USM lens. It’s compatible with the PZ-E1 power zoom adapter, which offers more natural and controllable zooming performance, especially prized when shooting video. You’ll also find kits with the 18-55mm bundled with a 55-250mm f/4-5.6 IS STM lens for about $450 more than the body alone (although Canon has been known to offer rebates of up to $150 on the package). (See Figure 6.3.)

Those looking for a longer zoom range might opt to pay an additional $700 for the older Canon EF-S 18-200mm f/3.5-5.6 IS lens, which provides a very useful 11X zoom range. Some buyers don’t need quite that zoom range and save a few dollars by purchasing the Canon EF 28-135mm f/3.5-5.6 IS USM lens ($600). The latter lens has one advantage. EF lenses like the 28-135mm zoom can also be used with any full-frame camera you add/migrate to at a later date. You’ll learn the difference later in this chapter.

Figure 6.2 The Canon EF-S 18-55mm f/3.5-5.6 IS STM autofocus lens ships as a basic kit lens for entry-level Canon cameras, including the 90D.

Figure 6.3 Some vendors are including the Canon EF-S 55-250mm f/4-5.6 IS STM lens in a bundle with some kits.

So, depending on which category you fall into, you’ll need to make a decision about what kit lens to buy, or decide what other kind of lenses you need to fill out your existing complement of Canon optics. This section will cover “first lens” concerns, while later in the chapter we’ll look at “add-on lens” considerations.

When deciding on a first lens, there are several factors you’ll want to consider:

- Cost. You might have stretched your budget a bit to purchase your 90D, so you might want to keep the cost of your first lens fairly low. Fortunately, as I’ve noted, there are excellent lenses available that will add from $100 to $600 to the price of your camera if purchased at the same time.

- Zoom range. If you have only one lens, you’ll want a fairly long zoom range to provide as much flexibility as possible. Fortunately, the two most popular basic lenses for the 90D have 3X to 5X zoom ranges, extending from moderate wide-angle/normal out to medium telephoto. These are fine for everyday shooting, portraits, and some types of sports.

- Adequate maximum aperture. You’ll want an f/stop of at least f/3.5 to f/4 for shooting under fairly low-light conditions. The thing to watch for is the maximum aperture when the lens is zoomed to its telephoto end. You may end up with no better than an f/5.6 maximum aperture. That’s not great, but you can often live with it.

- Image quality. Your starter lens should have good image quality, befitting a camera with 33MP of resolution, because that’s one of the primary factors that will be used to judge your photos. Even at a low price, the several different lenses sold with the 90D as a kit include extra-low dispersion glass and aspherical elements that minimize distortion and chromatic aberration; they are sharp enough for most applications. If you read the user evaluations in the online photography forums, you know that owners of the kit lenses have been very pleased with their image quality.

- Size matters. A good walking-around lens is compact in size and light in weight.

- Fast/close focusing. Your first lens should have a speedy autofocus system (which is where the ultrasonic motor/USM or STM system found in many moderately priced Canon lenses is an advantage). Close focusing (to 12 inches or closer) will let you use your basic lens for some types of macro photography.

You can find comparisons of the lenses discussed in the next section, as well as third-party lenses from Sigma, Tokina, Tamron, and other vendors, in online groups and websites. I’ll provide my recommendations but obtaining more information from these additional sources is always helpful when making a lens purchase, because, while camera bodies come and go, lenses may be a lifetime addition to your kit.

Buy Now, Expand Later

The 90D is commonly available with several good, basic lenses that can serve you well as a “walk-around” lens (one you keep on the camera most of the time, especially when you’re out and about without your camera bag). The number of options available to you is actually quite amazing, even if your budget is limited to about $100 to $500 for your first lens. The list that follows outlines your primary choices in Canon’s EF-S (APS-C) lineup. I’ll tell you more about your EF (full-frame) options later in this chapter.

- Canon EF-S 18-55mm f/4-5.6 IS STM lens. This lens, as well as the previous model with an f/3.5-5.6 aperture range (shown earlier in Figure 6.2), boasts the improved STM stepper motor technology that Canon video fans have found to be so useful. It has image stabilization that can counter camera shake by providing the vibration-stopping capabilities of a shutter speed four stops faster than the one you’ve dialed in. That is, with image stabilization activated, you can shoot at 1/30th second and eliminate camera shake as if you were using a shutter speed of 1/250th second. (At least, that’s what Canon claims; I usually have slightly less impressive results.) Of course, IS doesn’t freeze subject motion—that basketball player driving for a lay-up will still be blurry at 1/30th second, even though the effects of camera shake will be effectively nullified. But this lens is an all-around good choice if your budget is tight. If you don’t bundle it with the 90D body (for about a $100 premium), it can be purchased separately for roughly $250. Canon also offers the EF-S 18-55mm f/3.5-5.6 IS II version, with the less desirable DC micro motor for about $50 less.

- Canon EF-S 18-135mm f/3.5-5.6 IS USM lens. This one, priced at about $350 when purchased in a kit, or available separately for about $600, is light, compact (you can see it mounted on the 90D in Figure 6.4), and covers a useful range from true wide-angle to intermediate telephoto. As with Canon’s other affordable zoom lenses, image stabilization partially compensates for the slow f/5.6 maximum aperture at the telephoto end, by allowing you to use longer shutter speeds to capture an image under poor lighting conditions. You’ll want this lens if you’re shooting video, as it is compatible with the PZ-E1 power zoom adapter, as I mentioned earlier.

Figure 6.4 The EF-S 18-135mm f/3.5-5.6 IS USM lens is affordable and features near-silent autofocus that’s perfect for video shooting.

- Canon EF-S 18-200mm f/3.5-5.6 IS lens. This one, priced at about $700, has been popular as a basic lens for the 90D, because it’s light, compact, and covers a full range from true wide-angle to long telephoto. Image stabilization keeps your pictures sharp at the long end of the zoom range, allowing the longer shutter speeds that the f/5.6 maximum aperture demands at 200mm. Automatic panning detection turns the IS feature off when panning in both horizontal and vertical directions. An improved “Super Spectra Coating” minimizes flare and ghosting, while optimizing color rendition.

- Canon EF-S 17-85mm f/4-5.6 IS USM lens. This older lens (introduced in 2004 with the EOS 20D) is a very popular “basic” lens still sold for the 90D. It appears to be headed out to pasture as I write this, as some retailers are offering steep discounts from its MSRP $600 price tag. The allure here is the longer telephoto range, coupled with the built-in image stabilization, which allows you to shoot rock-solid photos at shutter speeds that are at least two or three notches slower than you’d need normally (say, 1/8th second instead of 1/30th or 1/60th second), as long as your subject isn’t moving. It also has a quiet, fast, reliable ultrasonic motor (more on that later, too).

- Canon EF-S 15-85mm f/3.5-5.6 IS USM lens. This successor to the 17-85mm lens has a slightly wider perspective (at 15mm) at a steeper price ($800). Optical quality is improved over the earlier lens, with three aspheric elements (versus one dual-sided aspheric element), and one ultra-low dispersion element which reduces chromatic aberration and offers better color fidelity.

- Canon EF-S 10-22mm f/3.5-4.5 USM lens. Priced at about $650, this lens is a general-purpose wide-angle that focuses as close as 9.5 inches, which I like for deliberate “perspective distortion” effects in which objects nearest to the lens are huge compared to those in the background. It features fast autofocus but offers full-time manual focus so you can fine-tune your plane of focus (which is often the case for close-up images).

- Canon EF-S 10-18mm f/4.5-5.6 IS STM lens. If Canon’s higher-end wide angle is too rich for your budget, you can find this bargain alternative for about $300. Its maximum aperture is only f/4.5 (vs. f/3.5) and its focal range extends only to 18mm (instead of 22mm), but it offers full-time manual focus for quick adjustments like its more expensive sibling, and optical quality is good even though it has two fewer aspherical elements. (I’ll cover this lens later in this chapter.)

- Canon EF-S 17-55mm f/2.8 ISM USM lens. This one is a definite step up from the 18-55mm kit lens, starting with its constant f/2.8 maximum aperture. That’s two stops faster than the kit lens at 55mm, so if you’re using this optic for a head-and-shoulders portrait (it is the full-frame equivalent of an 88mm lens), the f/2.8 aperture will allow you to blur the background more easily. (Bokeh—the rendition of out-of-focus highlights, is excellent, too.) Of course, at $880, it costs a significant fraction of the price of the 90D body alone, but it’s a great walk-around lens.

- Canon EF-S 55-250mm f/4-5.6 IS II/IS STM lens. Both these optics are image-stabilized EF-S lenses, providing the longest focal range in the EF-S range to date, and feature the Canon Image Stabilizer. The IS II version can set you back less than $300 (I’ve seen it for as little as $180), so it’s a bargain for a lens that includes stabilization. If you can afford only two lenses, this one and the 18-55mm kit lens make a good basic set.

Canon also offers the EF-S 55-250mm f/4-5.6 IS STM version, which has the desirable quiet STM motor in place of the other less expensive model’s noisier DC Micromotor. (I’ll address motor comparisons later in this chapter.)

- Canon EF-S 24mm f/2.8 STM lens. I love this lens for street photography, and at $150 it’s worth adding to your kit just for that. It’s thin (pancake style), has a fast f/2.8 aperture, and a quiet STM motor that’s unobtrusive for both still and video photography.

- Canon EF-S 35mm f/2.8 Macro IS STM lens. Most 90D owners will want to add a macro lens to their kit, and this $350 optic, with a built-in Macro Lite LED on its front, is a gem. It focuses down to 5.1 inches to provide life-size (1:1) magnification, and stops down to f/32 when you need extra depth-of-field (and can sacrifice a tiny bit of sharpness due to a phenomenon called diffraction, which is worst at a lens’s smallest apertures. When shooting close-ups, you’ll often want to fine-tune the focus plane, and this lens offers Canon’s full-time manual focus feature.

- Canon EF-S 60mm f/2.8 Macro USM lens. If you’re shooting skittish critters (such as insects), or need to put a little more distance between you and your subject to allow for more options for lighting, the longer focal length of this $470 lens can come in handy. It focuses down to 7.9” for 1:1 magnification. This lens uses an internal focusing design so your lens doesn’t get longer (and closer to your subject) as you focus closer.

What Lenses Can You Use?

The previous section helped you sort out what EF-S lenses you need to buy with your 90D (assuming you already didn’t own any Canon lenses). Now, you’re probably wondering what other lenses can be added to your growing collection (trust me, it will grow). You need to know which lenses are suitable and, most importantly, which lenses are fully compatible with your 90D.

With the Canon 90D, the compatibility issue is a simple one: It accepts any lens with the EF-S designation, as well as Canon’s EF full-frame lenses, with full availability of all autofocus, auto aperture, autoexposure, and image-stabilization features (if present). It’s comforting to know that any EF (for full-frame or cropped sensors) or EF-S (for cropped sensor cameras only) lens will work as designed with your camera. As I noted at the beginning of the chapter, that’s more than 140 million lenses!

But wait, there’s more. You can also attach Nikon F-mount, Leica R, Olympus OM, and M42 (“Pentax screw mount”) lenses with a simple adapter, if you don’t mind losing automatic focus and aperture control. If you use one of these lenses, you’ll need to focus manually (even if the lens operates in Autofocus mode on the camera it was designed for) and adjust the f/stop to the aperture you want to use to take the picture. That means that lenses that don’t have an aperture ring (such as Nikon G-series lenses) must be used only at their maximum aperture if you use them with a simple adapter. However, Novoflex makes expensive adapter rings (the Nikon-Lens-on-Canon-Camera version is called EOS/NIK NT) with an integral aperture control that allows adjusting the aperture of lenses that do not have an old-style aperture ring. Expect to pay $250 to $300 for an adapter of this type. Should you decide to pick up a new Canon EOS-M mirrorless camera, you’ll be able to get double-duty with your EF and EF-S lenses, too, with an adapter that will allow you to use the same lenses on your 90D and companion EOS-M cameras.

Because of the limitations imposed on using “foreign” lenses on your 90D, you probably won’t want to make extensive use of them, but an adapter can help you when you really, really need to use a particular focal length but don’t have a suitable Canon-compatible lens. For example, I occasionally use an older 400mm lens that was originally designed for the Nikon line on my 90D. The lens needs to be mounted on a tripod for steadiness, anyway, so its slower operation isn’t a major pain. Another good match is the 105mm Micro-Nikkor I sometimes use with my Canon 90D. Macro photos, too, are most often taken with the camera mounted on a tripod, and manual focus makes a lot of sense for fine-tuning focus and depth-of-field. Because of the contemplative nature of close-up photography, it’s not much of an inconvenience to stop down to the taking aperture just before exposure.

The restrictions on use of lenses within Canon’s own product line (as well as lenses produced for earlier Canon SLRs by third-party vendors) are fairly clear-cut. The 90D cannot be used with any of Canon’s earlier lens mounting schemes for its film cameras, including the immediate predecessor to the EF mount, the FD mount (introduced with the Canon F1 in 1964 and used until the Canon T60 in 1990), FL (1964–1971), or the original Canon R mount (1959–1964). While you’ll find FD-to-EF adapters for about $40, you’ll lose so many functions that it’s rarely worth the bother.

In retrospect, the switch to the EF mount seems like a very good idea, as the initial EOS film cameras can now be seen as the beginning of Canon’s rise to eventually become the leader in film and (later) digital SLR cameras. By completely revamping its lens mounting system, the company was able to take advantage of the latest advances in technology without compromise.

WHY SO MANY LENS MOUNTS?

Four different lens mounts in 40-plus years (five, if you count the EF-M mount for the new EOS-M cameras) might seem like a lot of different mounting systems, especially when compared to the Nikon F mount of 1959, which retained quite a bit of compatibility with that company’s film and digital camera bodies during that same span. However, in digital photography terms, the EF mount itself is positively ancient, having remained reasonably stable for more than 25 years. Lenses designed for the EF system work reliably with every EOS film and digital camera ever produced.

However, at the time, yet another lens mount switch, especially a change from the traditional breech system to a more conventional bayonet-type mount, was indeed a daring move by Canon. One of the reasons for staying with a particular lens type is to “lock” current users into a specific camera system. By introducing the EF mount, Canon in effect cut loose every photographer in its existing user base. If they chose to upgrade, they were free to choose another vendor’s products and lenses. Only satisfaction with the previous Canon product line and the promise of the new system would keep them in the fold.

For example, when the original EF bayonet mount was introduced in 1987, the system incorporated new autofocus technology (EF actually stands for “electro focus”) in a more rugged and less complicated form. A tiny motor was built into the lens itself, eliminating the need for mechanical linkages with the camera. Instead, electrical contacts are used to send power and the required focusing information to the motor. That’s a much more robust and resilient system that made it easier for Canon to design faster and more accurate autofocus mechanisms just by redesigning the lenses.

EF vs. EF-S

Today, in addition to its original EF lenses, Canon offers lenses that use the EF-S (the S stands for “short back focus”) mount, with the chief difference being (as you might expect) lens components that extend farther back into the camera body of some of Canon’s latest digital cameras (specifically those with smaller than full-frame sensors), such as the 90D. As I’ll explain next, this refinement allows designing more compact, less-expensive lenses especially for those cameras, but not for models that include current full-frame cameras.

Canon’s EF-S lens mount variation was born in 2003, when the company virtually invented the consumer-oriented digital SLR category by introducing the original EOS 300D/Digital Rebel, a dSLR that cost less than $1,000 with lens at a time when all other interchangeable-lens digital cameras (including the 90D’s “grandparent,” the original EOS 10D) were priced closer to $2,000 with a basic lens. Like the EOS 10D, the EOS 90D features a smaller-than-full-frame sensor with a 1.6X crop factor (Canon calls this format APS-C). But the EOS Digital Rebel accepted lenses that took advantage of the shorter mirror found in APS-C cameras, with elements of shorter focal length lenses (wide angles) that extended into the camera, space that was off limits in other models because the mirror passed through that territory as it flipped up to expose the shutter and sensor. (Canon even calls its flip-up reflector a “half mirror.”)

In short (so to speak), the EF-S mount made it easier to design less-expensive wide-angle lenses that could be used only with 1.6X-crop cameras, and featured a simpler design and reduced coverage area suitable for those non-full-frame models. The new mount made it possible to produce lenses like the ultra-wide EF-S 10-22mm f/3.5-4.5 USM lens, which has the equivalent field of view as a 16mm-35mm zoom on a full-frame camera. (See Figure 6.5.)

Suitable cameras for EF-S lenses include all recent non-full-frame models. The EF-S lenses cannot be used with any of Canon’s full-frame dSLR cameras, nor with a few older models, including the APS-C-sensor EOS 10D, and the discontinued Canon dSLRs that used the APS-H format with a 1.3X crop factor. However, EF-S lenses can be safely used on Canon’s full-frame mirrorless models, such as the Canon EOS R, when used with one of the three EF-to-RF mount adapters.

It’s easy to tell an EF lens from an EF-S lens: The latter incorporate EF-S into their name! Plus, EF lenses have a raised red dot on the barrel that is used to align the lens with a matching dot on the camera when attaching the lens. EF-S lenses and compatible bodies use a white square instead. Some EF-S lenses also have a rubber ring at the attachment end that provides a bit of weather/dust sealing and protects the back components of the lens if a user attempts to mount it on a camera that is not EF-S compatible.

Figure 6.5 The EF-S 10-22mm f/3.5-4.5 USM ultra-wide lens was made possible by the shorter back-focus difference offered by the original Digital Rebel and subsequent Canon 1.6X “cropped-sensor” models.

Ingredients of Canon’s Alphanumeric Soup

The actual product names of individual Canon lenses are fairly easy to decipher; they’ll include either the EF or EF-S designation (or RF for mirrorless models), the focal length or focal length range of the lens, its maximum aperture, and some other information. Additional data may be engraved or painted on the barrel or ring surrounding the front element of the lens. Here’s a decoding of what the individual designations mean:

- EF/EF-S/RF. RF lenses are those designed for the EOS R and RP. They cannot be mounted on any other EOS cameras, other than future mirrorless models not yet announced. If the lens is marked EF, it can safely be used on any Canon EOS dSLR or SLR, film or digital, but requires a mount adapter to use with the EOS R and RP. If it is an EF-S lens, it should be used only on an EF-S-compatible camera, or an EOS mirrorless model with a mount adapter.

- Focal length. Given in millimeters or a millimeter range, such as 60mm in the case of a popular Canon macro lens, or 24-105mm, used to describe a medium-wide to short-telephoto zoom.

- Maximum aperture. The largest f/stop available with a particular lens is given in a string of numbers that might seem confusing at first glance. For example, you might see 1:1.8 for a fixed-focal length (prime) lens, and 1:4.5-5.6 for a zoom. The initial 1: signifies that the f/stop given is actually a ratio or fraction (in regular notation, f/replaces the 1:), which is why a 1:2 (or f/2) aperture is larger than a 1:4 (or f/4) aperture—just as 1/2 is larger than 1/4. With most zoom lenses, the maximum aperture changes as the lens is zoomed to the telephoto position, so a range is given instead: 1:4.5-5.6. (Some zooms, called constant aperture lenses, keep the same maximum aperture throughout their range.)

- DS (Defocus Smoothing). This is Canon’s terminology for technology that allows improved bokeh (out-of-focus highlights).

- Autofocus type. Most newer Canon lenses that aren’t of the bargain-basement type use Canon’s ultrasonic motor autofocus system (more on that later) and are given the USM designation. If USM does not appear on the lens or its model name, the lens may use the less sophisticated AFD (arc-form drive) autofocus system or the micromotor (MM) drive mechanism. The newer STM designation indicates a stepper-motor drive, which is quieter and especially useful for video.

- Series. Canon adds a Roman numeral to many of its products to represent an updated model with the same focal length or focal length range, so some lenses will have a II or III added to their name. The revamped EF 24-70mm f/2.8L II USM lens is an example of a series update.

SORTING THE MOTOR DRIVES

Incorporating the autofocus motor inside the lens was an innovative move by Canon, and this allowed the company to produce better and more sophisticated lenses as technology became available to upgrade the focusing system. As a result, you’ll find four different types of motors in Canon-designed lenses, each with cost and practical considerations. Some RF lenses are hybrids, incorporating both USM and STM technology.

- AFD (Arc-form drive) and Micromotor (MM) drives are built around tiny versions of electromagnetic motors, which generally use gear trains to produce the motion needed to adjust the focus of the lens. Both are slow, noisy, and not particularly effective with larger lenses. Manual focus adjustments are possible only when the motor drive is disengaged.

- Micromotor ultrasonic motor (USM) drives use high-frequency vibration to produce the motion used to drive the gear train, resulting in a quieter operating system at a cost that’s not much more than that of electromagnetic motor drives. Except for a couple lenses that have a slipping clutch mechanism, manual focus with this kind of system is possible only when the motor drive is switched off and the lens is set in Manual mode. This is the kind of USM system you’ll find in lower-cost lenses.

- Ring ultrasonic motor (USM) drives, available in two different types (electronic focus ring USM and ring USM), also use high-frequency movement, but generate motion using a pair of vibrating metal rings to adjust focus. Both variations allow a feature called Full Time Manual (FTM) focus, which lets you make manual adjustments to the lens’s focus even when the autofocus mechanism is engaged. With electronic focus ring USM, manual focus is possible only when the lens is mounted on the camera and the camera is turned on; the focus ring of lenses with ring USM can be turned at any time.

- Stepper motor (STM) drives. In autofocus mode, the precision motor of STM lenses, along with a new aperture mechanism, allows lenses equipped with this technology to focus quickly, accurately, silently, and with smooth continuous increments. If you think about video capture, you can see how these advantages pay off. Silent operation is a plus, especially when noise from autofocusing can easily be transferred to the camera’s built-in microphones through the air or transmitted through the body itself. In addition, because autofocus is often done during capture, it’s important that the focus increments are continuous. USM motors are not as smooth but are better at jumping quickly to the exact focus point. You can adjust focus manually, using a focus-by-wire process. As you rotate the focus ring, that action doesn’t move the lens elements; instead, your rotation of the ring sends a signal to the motor to change the focus.

- Pro quality. Canon’s more expensive lenses with more rugged construction and higher optical quality, intended for professional use, include the letter L (for “luxe” or “luxury”) in their product name. You can further differentiate these lenses visually by a red ring around the lens barrel and the off-white color of the metal barrel itself in virtually all telephoto L-series lenses. (Some L-series lenses have shiny or textured black plastic exterior barrels.) Internally, every L lens includes at least one lens element that is built of ultra-low dispersion glass, is constructed of expensive fluorite crystal, or uses an expensive ground (not molded) aspheric (non-spherical) lens component.

- Filter size. You’ll find the front lens filter thread diameter in millimeters included on the lens, preceded by a Ø symbol, as in Ø67 or Ø77. One advantage of Canon’s L lenses is that many of them use 77mm filters, so you don’t have to purchase a new set (or step-up/step-down adapter rings) each time you buy a lens.

- Special-purpose lenses. Some Canon lenses are designed for specific types of work, and they include appropriate designations in their names. For example, close-focusing lenses incorporate the word Macro into their name. Lenses with perspective control features preface the lens name with T-S (for tilt-shift). Lenses with built-in image-stabilization features, such as the nifty EF 28-300mm f/3.5-5.6L IS USM Telephoto Zoom include IS in their product names.

Select EF Lenses

If the APS-C lenses available from Canon and other vendors aren’t sufficient, you can always consider EF lenses, which work equally well on both crop-sensor models like the 90D, as well as any full-frame Canon cameras you may own or buy in the future. One important thing to re-emphasize is that Canon has been producing EF lenses for a very long time, and some excellent lenses have been replaced with newer models or dropped from the Canon lineup entirely. If you want to choose from the broadest variety of lenses at reduced prices, you should consider buying gently used optics.

I highly recommend KEH Camera in Smyrna, Georgia, as a source for affordable used gear. I’ve purchased many lenses from their website (www.keh.com). Their prices may not be the lowest available, but you’ll save significantly from the new price for the same lens, and the company is famous for exceeding their own lens grading standards: the lenses I’ve purchased from them listed as Excellent were difficult to tell from new, and their “Bargain” optics often show only minor wear and near-perfect glass. For each lens you’re considering, you can usually select from three or more different grades, plus choose lenses with or without hoods and/or front and rear caps. Because of the ready availability of used and discontinued lenses for Canon full-frame models, I’m going to cast a broad net when making my recommendations for lenses you should consider. Canon’s best-bet lenses are as follows:

- Canon EF 17-40mm f/4L USM lens. Not everyone needs a wide-angle to medium telephoto lens, and this $799 optic is perfect for those who tend to see the world from a wide-angle perspective. It provides a broader 104-degree field of view than your typical walk-around lens (which usually starts at around 24mm) and zooms only to a near-normal 40mm. Its f/4 constant maximum aperture (it delivers f/4 at every zoom position) is large enough for much low-light shooting, particularly since it is sharp wide open. It focuses down to about 11 inches.

- Canon Zoom Wide-Angle Telephoto EF 24-70mm f/2.8L II USM lens. I couldn’t leave the latest version of this premium lens out of the mix, even though it costs $1,700. As part of Canon’s L-series line, it offers better sharpness over its focal range than many of the other lenses in this list. Best of all, it’s fast (for a zoom), with an f/2.8 maximum aperture that doesn’t change as you zoom out. Unlike some other lenses, which may offer only an f/5.6 maximum f/stop at their longest zoom setting, this is another constant aperture lens, which retains its maximum f/stop. The added sharpness, constant aperture, and ultra-smooth USM motor are what you’re paying for with this lens.

- Canon EF 24-85mm f/3.5-4.5 USM Autofocus Wide-Angle Telephoto Zoom lens. If you can get by with wide-angle to short telephoto range, this older (“classic”) consumer-grade lens might suit you. It can often be found used in the $300 price range and offers a useful range of focal lengths.

- Canon EF 28-105mm f/3.5-4.5 II USM Autofocus Wide-Angle Telephoto Zoom lens. Discontinued only a few years ago, this lens is a little slower than its 28-105mm L-class counterpart, but it’s priced roughly in the range of the 24-85mm lens mentioned earlier and offers more reach.

- Canon EF 28-135mm f/3.5-5.6 IS USM Image-Stabilized Autofocus Wide-Angle Telephoto Zoom lens. Image stabilization is especially useful at longer focal lengths, which makes this lens worth its $479 price tag. Several retailers are packing this lens with the EOS R as a kit.

- Canon EF 28-200mm f/3.5-5.6 USM Autofocus Wide-Angle Telephoto Zoom lens. If you want one affordable lens to do everything except ultra-wide-angle photography, this discontinued 7X zoom lens can be found used for around $250.

- Canon EF 55-200mm f/4.5-5.6 II USM Telephoto Zoom lens. This one goes from normal to medium-long focal lengths. It features a desirable ultrasonic motor. Best of all, it’s very affordable at an MSRP of $349.

- Canon EF 40mm f/2.8 STM lens. This fast prime lens (less than $200) has the quiet STM motor, making it perfect as a wide/normal lens for video. It’s cheap enough to keep around as a “pancake” walk-around lens for street photography, even if you already own the Canon EF-S 24mm f/2.8 STM described earlier. It’s a bit longer and gives you more reach for capturing slightly more distant subjects discreetly. (See Figure 6.6.)

- Canon EF 50mm f/1.8 STM lens. If the 50mm-range short telephoto look is not your cup of tea for everyday use, you can skip Canon’s f/1.4 and f/1.2 options, and add this $125 lens to your kit for less than you might pay for a high-quality 77mm polarizing filter.

Figure 6.6 A fast “pancake” lens like Canon’s EF-S 24mm f/2.8 or EF 40mm f/2.8 STM (shown) make great lenses for street photography.

More Winners

Although all the five or six dozen readily available Canon lenses are beyond the scope of this book, the company makes a variety of other interesting lenses. Here are some of my favorites.

- EF 8-15mm f/4L Fish-eye USM lens. Yup, a fish-eye zoom. For a mere $1,249 you can buy the coolest lens you’ll own, and start capturing some mind-bending images, or just add some interest to a simple landscape shot, like the one in Figure 6.7.

Figure 6.7 Because lines at the center of the frame aren’t bent, some fish-eye shots don’t look like fish-eye images on first glance.

- EF 100-400mm f/4.5-5.6L II USM lens. A 400mm lens really comes in handy when shooting field sports, wildlife, and other distant subjects. This $2,199 lens is long enough and fast enough to prove useful in a variety of demanding situations. And it’s a lot more affordable than Canon’s “exotic” lenses in this range, such as the EF 400mm f/2.8L II USM lens ($11,999). Although, at three pounds, this lens isn’t really the boat anchor you might think it is; you’ll want to mount it on a sturdy tripod (for wildlife) or monopod (for sports) to get the sharpest images.

- EF 85mm f/1.2L II USM lens. This exquisite lens is the perfect optic for head-and-shoulders portraits, with its remarkable bokeh, excellent sharpness, and shallow depth-of-field for selective focus effects. The $1,999 MSRP lens’s huge maximum aperture means you can hand-hold it for sports, portraits, or other types of shooting. As I write this, there are rumors that Canon is about to introduce an updated 85mm f/1.4L lens. Price and other specs are unknown, but the new lens is sharper wide open and has comparable bokeh; many photographers will be willing to give up the f/1.2 version’s slight maximum aperture advantage for an all-new design.

- TS-E 90mm f/2.8 lens (or any other tilt-shift lens). Manual focus won’t bother you with this lens, because the most exciting capability of any tilt-shift lens is to let you manipulate the plane of focus in useful and/or interesting ways. Whether you want to correct the focal plane for architectural images, create “miniature” special effects, or produce unusual selective focus in portraits, these lenses offer interesting capabilities. The 90mm f/2.8 optic at $1,399 is relatively affordable, but Canon also offers 17mm, 24mm, and 45mm TS-E lenses for around $1,399 to $2,149.

- A macro. Canon offers an assortment of full-frame macro lenses, priced at less than $400 to less than $1,399, including the unique MP-E 65mm f/2.8 1-5X macro for close-up use only (it doesn’t focus to infinity). All are non-zooms and they range in focal length from 50mm to 180mm, and one (the EF 100mm f/2.8L Macro IS USM) includes image stabilization for hand-held work. Choose your lens based on how close you want to work from your subject, and their closest focusing distance. Everybody needs a macro, especially for a rainy day when you want to photograph your collection of saltshakers rather than venture out into the elements.

What Lenses Can Do for You

A saner approach to expanding your lens collection is to consider what each of your options can do for you and then choosing the type of lens that will really boost your creative opportunities. Here’s a general guide to the sort of capabilities you can gain by adding a lens to your repertoire.

- Wider perspective. Your 18-55mm f/3.5-5.6 or 17-85mm f/4-5.6 or 18-200mm lens has served you well for moderate wide-angle shots. Now you find your back is up against a wall and you can’t take a step backward to take in more subject matter. Perhaps you’re standing on the rim of the Grand Canyon, and you want to take in as much of the breathtaking view as you can. You might find yourself just behind the baseline at a high school basketball game and want an interesting shot with a little perspective distortion tossed in the mix. There’s a lens out there that will provide you with what you need, such as the EF-S 10-22mm f/3.5-4.5 USM zoom (about $650). If you want to stay in the sub-$800 price category, you’ll need something like the Sigma Super Wide-Angle 10-20mm f/4-5.6 EX DC HSM autofocus lens. The two lenses provide the equivalent of a 16mm to 32/35mm wide-angle view. For a distorted view, there is the Canon Fish-eye EF 15mm f/2.8 autofocus, with a similar lens available from Sigma, which offers an extra-wide circular fish-eye, and the Sigma Fish-eye 8mm f/3.5 EX DG Circular Fish-eye. Your extra-wide choices may not be abundant, but they are there. Figure 6.8, top, shows the perspective you get from a wide-angle, non-fish-eye lens.

Figure 6.8 An ultra-wide-angle lens provided this view (top). The center photo, taken from roughly the same distance, shows the view using a short telephoto lens. A longer telephoto lens captured this closer view from approximately the same shooting position (bottom).

- Bring objects closer. A long lens brings distant subjects closer to you, offers better control over depth-of-field, and avoids the perspective distortion that wide-angle lenses provide. They compress the apparent distance between objects in your frame. In the telephoto realm, Canon is second to none, with a dozen or more offerings in the sub-$650 range, including the Canon EF 100-300mm f/4.5-5.6 USM autofocus and Canon EF 70-300mm f/4-5.6 IS USM autofocus telephoto zoom lenses, and a broad array of zooms and fixed-focal length optics if you’re willing to spend up to $1,000 or a bit more. Don’t forget that the 90D’s crop factor narrows the field of view of all these lenses, so your 70-300mm lens looks more like a 112-480mm zoom through the viewfinder. Figures 6.8 (center) and 6.8 (bottom) were taken from the same position as Figure 6.8, top, but with an 85mm and 500mm lens, respectively.

- Bring your camera closer. Macro lenses allow you to focus to within an inch or two of your subject. Canon’s best close-up lenses are all fixed focal length optics in the 50mm to 180mm range (including the well-regarded Canon EF-S 60mm f/2.8 compact and Canon EF 100mm f/2.8 USM macro autofocus lenses). But you’ll find macro zooms available from Sigma and others. They don’t tend to focus quite as close, but they provide a bit of flexibility when you want to vary your subject distance (say, to avoid spooking a skittish creature).

- Look sharp. Many lenses, particularly Canon’s luxury “L” line, are prized for their sharpness and overall image quality. While your run-of-the-mill lens is likely to be plenty sharp for most applications, the very best optics are even better over their entire field of view (which means no fuzzy corners), are sharper at a wider range of focal lengths (in the case of zooms), and have better correction for various types of distortion.

- More speed. Your Canon EF 100-300mm f/4.5-5.6 telephoto zoom lens might have the perfect focal length and sharpness for sports photography, but the maximum aperture won’t cut it for night baseball or football games, or, even, any sports shooting in daylight if the weather is cloudy or you need to use some unusually fast shutter speed, such as 1/4000th second. You might be happier with the Canon EF 100mm f/2 medium telephoto for close-range stuff, or even the pricier Canon EF 135mm f/2L. If money is no object, you can spring for Canon’s 400mm f/2.8 and 600mm f/4 L-series lenses (both with image stabilization and priced in the four- and five-figure stratosphere). Or, maybe you just need the speed and can benefit from an f/1.8 or f/1.4 lens in the 20mm-85mm range. They’re all available in Canon mounts (there’s even an 85mm f/1.2 and 50mm f/1.2 for the real speed demons). With any of these lenses you can continue photographing under the dimmest of lighting conditions without the need for a tripod or flash.

- Special features. Accessory lenses give you special features, such as tilt/shift capabilities to correct for perspective distortion in architectural shots. Canon offers four of these TS-E lenses in 17mm, 24mm, 45mm, and 90mm focal lengths, at more than $1,300 to $2,000 (and up) each. You’ll also find macro lenses, including the MP-E 65mm f/2.8 1-5x macro photo lens, a manual focus lens which shoots only in the 1X to 5X life-size range. If you want diffused images, check out the EF 135mm f/2.8 with two soft-focus settings. The fish-eye lenses mentioned earlier, and all IS (image-stabilized) lenses also count as special-feature optics. The recent Canon EF 8-15mm f/4L Fish-eye USM ultra-wide zoom lens is highly unusual in offering a zoomable fish-eye range. Tokina’s 10-17mm fish-eye zoom is its chief competitor; I’ve owned one and it is not in the same league in terms of sharpness and speed as the Canon optic.

Zoom or Prime?

Zoom lenses have changed the way serious photographers take pictures. One of the reasons that I own 12 SLR film bodies is that in ancient times it was common to mount a different fixed focal length prime lens on various cameras and take pictures with two or three cameras around your neck (or tucked in a camera case) so you’d be ready to take a long shot or an intimate close-up or wide-angle view on a moment’s notice, without the need to switch lenses. It made sense (at the time) to have a half dozen or so bodies (two to use, one in the shop, one in transit, and a couple backups). Zoom lenses of the time had a limited zoom range, were heavy, and not very sharp (especially when you tried to wield one of those monsters handheld).

That’s all changed today. Lenses like the razor-sharp Canon EF 28-300mm f/3.5-5.6L IS USM can boast 10X or longer zoom ranges, in a package that’s about 7 inches long, and while not petite at 3.7 pounds, it is quite usable handheld (especially with IS switched on). Although such a lens might seem expensive at close to $2,500, it’s much less costly than the six or so lenses it replaces.

When selecting between zoom and prime lenses, there are several considerations to ponder. Here’s a checklist of the most important factors. I already mentioned image quality and maximum aperture earlier, but those aspects take on additional meaning when comparing zooms and primes.

- Logistics. As prime lenses offer just a single focal length, you’ll need more of them to encompass the full range offered by a single zoom. More lenses mean additional slots in your camera bag, and extra weight to carry. Just within Canon’s line alone you can select from about a dozen general-purpose prime lenses in 28mm, 35mm, 50mm, 85mm, 100mm, 135mm, 200mm, and 300mm focal lengths, all of which are overlapped by the 28-300mm zoom I mentioned earlier. Even so, you might be willing to carry an extra prime lens or two in order to gain the speed or image quality that lens offers.

- Image quality. Prime lenses usually produce better image quality at their focal length than even the most sophisticated zoom lenses at the same magnification. Zoom lenses, with their shifting elements and f/stops that can vary from zoom position to zoom position, are in general more complex to design than fixed focal length lenses. That’s not to say that the best prime lenses can’t be complicated as well. However, the exotic designs, aspheric elements, low-dispersion glass, and Canon’s diffraction optics (DO) technology (a three-layer diffraction grating to better control how light is captured by a lens) can be applied to improving the quality of the lens, rather than wasting a lot of it on compensating for problems caused by the zoom process itself.

- Maximum aperture. Because of the same design constraints, zoom lenses usually have smaller maximum apertures than prime lenses, and the most affordable zooms have a lens opening that grows effectively smaller as you zoom in. The difference in lens speed verges on the ridiculous at some focal lengths. For example, the 18mm-55mm basic zoom gives you a 55mm f/5.6 lens when zoomed all the way out, while prime lenses in that focal length commonly have f/1.8 or faster maximum apertures. Indeed, the fastest f/2, f/1.8, f/1.4, and f/1.2 lenses are all primes, and if you require speed, a fixed focal length lens is what you should rely on. Figure 6.9 shows an image taken with a Canon 85mm f/1.8 Series EF USM telephoto lens.

- Speed. Using prime lenses takes time and slows you down. It takes a few seconds to remove your current lens and mount a new one, and the more often you need to do that, the more time is wasted. If you choose not to swap lenses, when using a fixed focal length lens, you’ll still have to move closer or farther away from your subject to get the field of view you want. A zoom lens allows you to change magnifications and focal lengths with the twist of a ring and generally saves a great deal of time.

- Special features. Prime lenses often have special features not found in zoom lenses, such as the tilt-shift capabilities of the Canon TS series lenses I mentioned earlier. For example, the EF 40mm f/2.8 STM lens boasts that smooth, silent autofocus motor described earlier in this chapter.

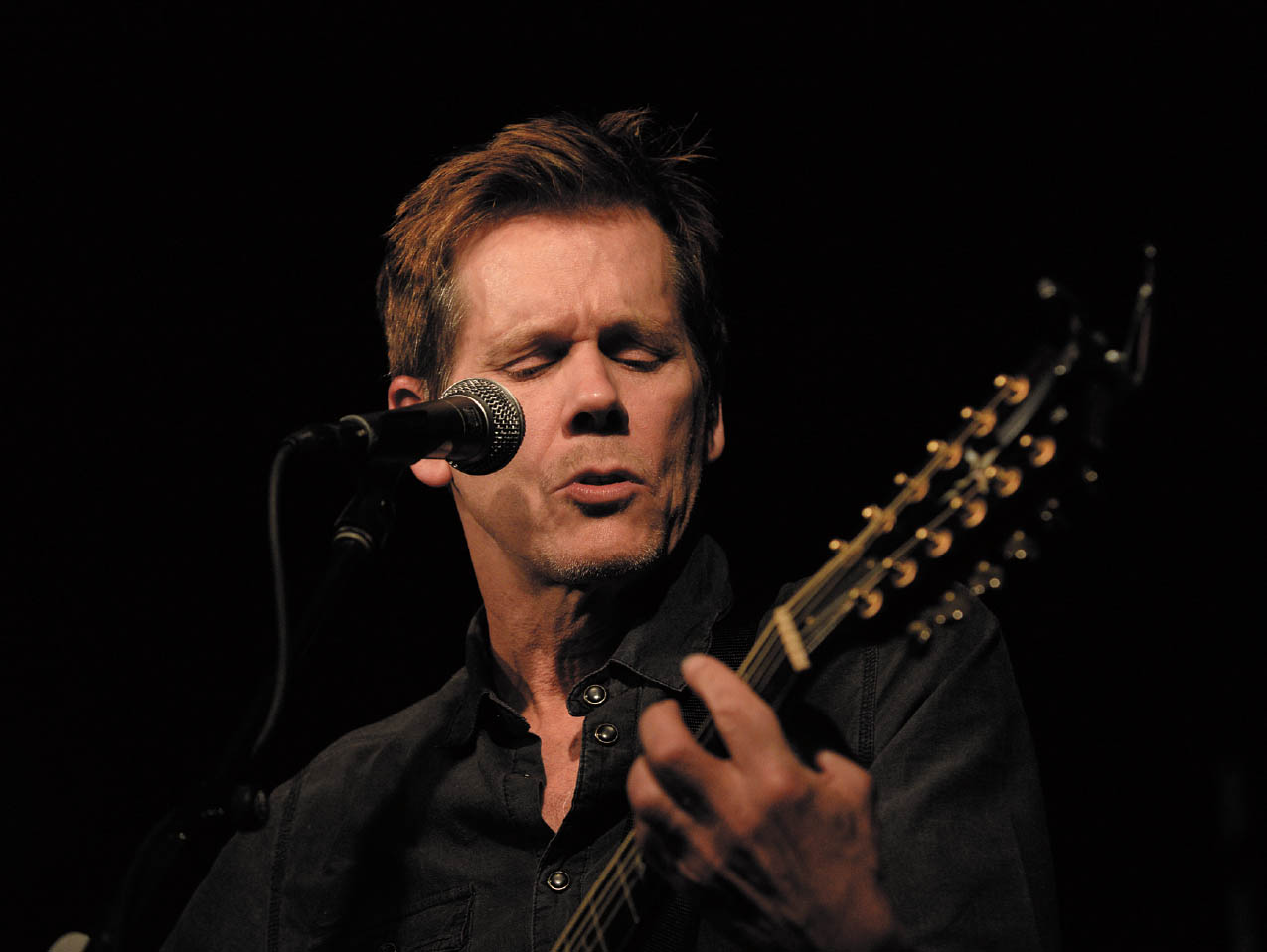

Figure 6.9 An 85mm f/1.8 lens was perfect for this handheld photo of the most obscure member of the Bacon Brothers Band.

Categories of Lenses

Lenses can be categorized by their intended purpose—general photography, macro photography, and so forth—or by their focal length. The range of available focal lengths is usually divided into three main groups: wide-angle, normal, and telephoto. Prime lenses fall neatly into one of these classifications. Zooms can overlap designations, with a significant number falling into the catch-all, wide-to-telephoto zoom range. This section provides more information about focal length ranges, and how they are used.

Any lens with an equivalent focal length of 10mm to 20mm is said to be an ultra-wide-angle lens; from about 20mm to 40mm (equivalent) is said to be a wide-angle lens. Normal lenses have a focal length roughly equivalent to the diagonal of the film or sensor, in millimeters, and so fall into the range of about 45mm to 60mm (on a full-frame camera). Telephoto lenses usually fall into the 75mm and longer focal lengths, while those from about 300mm to 400mm and longer often are referred to as super-telephotos.

Using Wide-Angle and Wide-Zoom Lenses

To use wide-angle prime lenses and wide zooms, you need to understand how they affect your photography. Here’s a quick summary of the things you need to know.

- More depth-of-field. Practically speaking, wide-angle lenses offer more depth-of-field at a particular subject distance and aperture. (But see the sidebar below for an important note.) You’ll find that helpful when you want to maximize sharpness of a large zone, but not very useful when you’d rather isolate your subject using selective focus (telephoto lenses are better for that).

- Stepping back. Wide-angle lenses have the effect of making it seem that you are standing farther from your subject than you really are. They’re helpful when you don’t want to back up or can’t because there are impediments in your way.

- Wider field of view. While making your subject seem farther away, as implied above, a wide-angle lens also provides a larger field of view, including more of the subject in your photos.

- More foreground. As background objects retreat, more of the foreground is brought into view by a wide-angle lens. That gives you extra emphasis on the area that’s closest to the camera. Photograph your home with a normal lens/normal zoom setting, and the front yard probably looks fairly conventional in your photo (that’s why they’re called “normal” lenses). Switch to a wider lens and you’ll discover that your lawn now makes up much more of the photo. So, wide-angle lenses are great when you want to emphasize that lake in the foreground, but problematic when your intended subject is located farther in the distance.

- Super-sized subjects. The tendency of a wide-angle lens to emphasize objects in the foreground, while de-emphasizing objects in the background, can lead to a kind of size distortion that may be more objectionable for some types of subjects than others. Shoot a bed of flowers up close with a wide angle, and you might like the distorted effect of the larger blossoms nearer the lens. Take a photo of a family member with the same lens from the same distance, and you’re likely to get some complaints about that gigantic nose in the foreground.

- Perspective distortion. When you tilt the camera so the plane of the sensor is no longer perpendicular to the vertical plane of your subject, some parts of the subject are now closer to the sensor than they were before, while other parts are farther away. So, buildings, flagpoles, or NBA players appear to be falling backward, as you can see in Figure 6.10. While this kind of apparent distortion (it’s not caused by a defect in the lens) can happen with any lens, it’s most apparent when a wide angle is used.

Figure 6.10 Tilting the camera back produces this “falling back” look in architectural photos.

- Steady cam. You’ll find that you can better handhold a wide-angle lens at slower shutter speeds, without need for image stabilization, than you can with a telephoto lens. The reduced magnification of the wide-lens or wide-zoom setting doesn’t emphasize camera shake like a telephoto lens does.

- Interesting angles. Many of the factors already listed combine to produce more interesting angles when shooting with wide-angle lenses. Raising or lowering a telephoto lens a few feet probably will have little effect on the appearance of the distant subjects you’re shooting. The same change in elevation can produce a dramatic effect for the much-closer subjects typically captured with a wide-angle lens or wide-zoom setting.

DOF IN DEPTH

The depth-of-field (DOF) advantage of wide-angle lenses is diminished when you enlarge your picture; believe it or not, a wide-angle image enlarged and cropped to provide the same subject size as a telephoto shot would have the same depth-of-field. Try it: take a wide-angle photo of a friend from a fair distance, and then zoom in to duplicate the picture in a telephoto image. Then, enlarge the wide shot so your friend is the same size in both. The wide photo will have the same DOF (and will have much less detail, too).

Avoiding Potential Wide-Angle Problems

Wide-angle lenses have a few quirks that you’ll want to keep in mind when shooting so you can avoid falling into some common traps. Here’s a checklist of tips for avoiding common problems:

- Symptom: converging lines. Unless you want to use wildly diverging lines as a creative effect, it’s a good idea to keep horizontal and vertical lines in landscapes, architecture, and other subjects carefully aligned with the sides, top, and bottom of the frame. That will help you avoid undesired perspective distortion. Sometimes it helps to shoot from a slightly elevated position, so you don’t have to tilt the camera up or down.

- Symptom: color fringes around objects. Lenses are often plagued with fringes of color around backlit objects, produced by chromatic aberration, which comes in two forms: longitudinal/axial, in which all the colors of light don’t focus in the same plane, and lateral/transverse, in which the colors are shifted to one side. Axial chromatic aberration can be reduced by stopping down the lens, but transverse chromatic aberration cannot. Both can be reduced by using lenses with low diffraction index glass (or UD elements, in Canon nomenclature) and by incorporating elements that cancel the chromatic aberration of other glass in the lens. For example, a strong positive lens made of low-dispersion crown glass (made of a soda-lime-silica composite) may be mated with a weaker negative lens made of high-dispersion flint glass, which contains lead. The 90D’s Lens Aberration Correction features, discussed in Chapter 8, can help correct for this and the next two problems in this list.

- Symptom: lines that bow outward. Some wide-angle lenses cause straight lines to bow outward, with the strongest effect at the edges. In fish-eye (or curvilinear) lenses, this defect is a feature. When distortion is not desired, you’ll need to use a lens that has corrected barrel distortion. Manufacturers like Canon do their best to minimize or eliminate it (producing a rectilinear lens), often using aspherical lens elements (which are not cross-sections of a sphere). You can also minimize less severe barrel distortion simply by framing your photo with some extra space all around, so the edges where the defect is most obvious can be cropped out of the picture.

- Symptom: dark corners and shadows in flash photos. The Canon EOS 90D’s built-in electronic flash is designed to provide even coverage for lenses as wide as 17mm. If you use a wider lens, you can expect darkening, or vignetting, in the corners of the frame. At wider focal lengths, the lens hood of some lenses (my 17mm-85mm lens is a prime offender) can cast a semi-circular shadow in the lower portion of the frame when using the built-in flash. Sometimes removing the lens hood or zooming in a bit can eliminate the shadow. Mounting an external flash unit, such as the mighty Canon Speedlite 600EX-RT II, can solve both problems, as it has zoomable coverage up to 114 degrees with the included adapter, sufficient for a 15mm rectilinear lens. Its higher vantage point eliminates the problem of lens hood shadow, too.

- Symptom: light and dark areas when using polarizing filter. If you know that polarizers work best when the camera is pointed 90 degrees away from the sun and have the least effect when the camera is oriented 180 degrees from the sun, you know only half the story. With lenses having a focal length of 10mm to 18mm (the equivalent of 16mm–28mm), the angle of view (107 to 75 degrees diagonally, or 97 to 44 degrees horizontally) is extensive enough to cause problems. Think about it: when a 10mm lens is pointed at the proper 90-degree angle from the sun, objects at the edges of the frame will be oriented at 135 to 41 degrees, with only the center at exactly 90 degrees. Either edge will have much less of a polarized effect. The solution is to avoid using a polarizing filter with lenses having an actual focal length of less than 18mm (or 28mm equivalent).

Using Telephoto and Tele-Zoom Lenses

Telephoto lenses also can have a dramatic effect on your photography, and Canon is especially strong in the long-lens arena, with lots of choices in many focal lengths and zoom ranges. You should be able to find an affordable telephoto or tele-zoom to enhance your photography in several different ways. Here are the most important things you need to know. In the next section, I’ll concentrate on telephoto considerations that can be problematic—and how to avoid those problems.

- Selective focus. Long lenses have reduced depth-of-field within the frame, allowing you to use selective focus to isolate your subject. You can open the lens up wide to create shallow depth-of-field (see Figure 6.11) or close it down a bit to allow more to be in focus. The flip side of the coin is that when you want to make a range of objects sharp, you’ll need to use a smaller f/stop to get the depth-of-field you need. Like fire, the depth-of-field of a telephoto lens can be friend or foe.

- Getting closer. Telephoto lenses bring you closer to wildlife, sports action, and candid subjects. No one wants to get a reputation as a surreptitious or “sneaky” photographer (except for paparazzi), but when applied to candids in an open and honest way, a long lens can help you capture memorable moments while retaining enough distance to stay out of the way of events as they transpire.

- Reduced foreground/increased compression. Telephoto lenses have the opposite effect of wide angles: they reduce the importance of things in the foreground by squeezing everything together. This compression even makes distant objects appear to be closer to subjects in the foreground and middle ranges. You can use this effect as a creative tool.

Figure 6.11 A wide f/stop helped isolate this Key deer.

- Accentuates camera shakiness. Telephoto focal lengths hit you with a double whammy in terms of camera/photographer shake. The lenses themselves are bulkier, more difficult to hold steady, and may even produce a barely perceptible see-saw rocking effect when you support them with one hand halfway down the lens barrel. Telephotos also magnify any camera shake. It’s no wonder that image stabilization is popular in longer lenses.

- Interesting angles require creativity. Telephoto lenses require more imagination in selecting interesting angles, because the “angle” you do get on your subjects is so narrow. Moving from side to side or a bit higher or lower can make a dramatic difference in a wide-angle shot but raising or lowering a telephoto lens a few feet probably will have little effect on the appearance of the distant subjects you’re shooting.

Avoiding Telephoto Lens Problems

Many of the “problems” that telephoto lenses pose are really just challenges and not that difficult to overcome. Here is a list of the seven most common picture maladies and suggested solutions.

- Symptom: flat faces in portraits. Head-and-shoulders portraits of humans tend to be more flattering when a focal length of 50mm to 85mm is used. Longer focal lengths compress the distance between features like noses and ears, making the face look wider and flat. A wide-angle might make noses look huge and ears tiny when you fill the frame with a face. So stick with 50mm to 85mm focal lengths, going longer only when you’re forced to shoot from a greater distance, and wider only when shooting three-quarters/full-length portraits, or group shots.

- Symptom: blur due to camera shake. Use a higher shutter speed (boosting ISO if necessary), consider an image-stabilized lens, or mount your camera on a tripod, monopod, or brace it with some other support. Of those three solutions, only the first will reduce blur caused by subject motion; an IS lens or tripod won’t help you freeze a race car in mid-lap.

- Symptom: color fringes. Chromatic aberration is the most pernicious optical problem found in telephoto lenses. There are others, including spherical aberration, astigmatism, coma, curvature of field, and similarly scary-sounding phenomena. The best solution for any of these is to use a better lens that offers the proper degree of correction or stop down the lens to minimize the problem. But that’s not always possible. Your second-best choice may be to correct the fringing in your favorite RAW conversion tool or image editor. The 90D’s own Lens Aberration Correction feature and Photoshop’s Lens Correction filter can help minimize both red/cyan and blue/yellow fringing.

- Symptom: lines that curve inward. Pincushion distortion is found in many telephoto lenses. You might find after a bit of testing that it is worse at certain focal lengths with your particular zoom lens. Like chromatic aberration, it can be partially corrected using tools like the 90D’s correction options, Photoshop’s Lens Correction filter, and Photoshop Elements’ Correct Camera Distortion filter.

- Symptom: low contrast from haze or fog. When you’re photographing distant objects, a long lens shoots through a lot more atmosphere, which generally is muddied up with extra haze and fog. That dirt or moisture in the atmosphere can reduce contrast and mute colors. Some feel that a skylight or UV filter can help, but this practice is mostly a holdover from the film days. Digital sensors are not sensitive enough to UV light for a UV filter to have much effect. So, you should be prepared to boost contrast and color saturation in your Picture Styles menu or image editor if necessary.

- Symptom: low contrast from flare. Lenses are furnished with lens hoods for a good reason: to reduce flare from bright light sources at the periphery of the picture area or completely outside it. Because telephoto lenses often create images that are lower in contrast in the first place, you’ll want to be especially careful to use a lens hood to prevent further effects on your image (or shade the front of the lens with your hand).

- Symptom: dark flash photos. Edge-to-edge flash coverage isn’t a problem with telephoto lenses as it is with wide angles. The shooting distance is. A long lens might make a subject that’s 50 feet away look as if it’s right next to you, but your camera’s flash isn’t fooled. You’ll need extra power for distant flash shots, and probably more power than your 90D’s built-in flash provides. The shoe-mount Canon 580EX II or 600EX-RT Speedlites, for example, can automatically zoom its coverage down to that of a medium telephoto lens, providing a theoretical full-power shooting aperture of about f/8 at 50 feet and ISO 400. (Try that with the built-in flash!)

Telephotos and Bokeh

Bokeh describes the aesthetic qualities of the out-of-focus parts of an image and whether out-of-focus points of light—circles of confusion—are rendered as distracting fuzzy discs or smoothly fade into the background. Boke is a Japanese word for “blur,” and the h was added to keep English speakers from rendering it monosyllabically to rhyme with broke. Although bokeh is visible in blurry portions of any image, it’s of particular concern with telephoto lenses, which, thanks to the magic of reduced depth-of-field, produce more obviously out-of-focus areas.

Bokeh can vary from lens to lens, or even within a given lens depending on the f/stop in use. Bokeh becomes objectionable when the circles of confusion are evenly illuminated, making them stand out as distinct discs, or, worse, when these circles are darker in the center, producing an ugly “doughnut” effect. (See Figure 6.12, left.) A lens defect called spherical aberration may produce out-of-focus discs that are brighter on the edges and darker in the center, because the lens doesn’t focus light passing through the edges of the lens exactly as it does light going through the center. (Mirror or catadioptric lenses also produce this effect.)

Other kinds of spherical aberration generate circles of confusion that are brightest in the center and fade out at the edges, producing a smooth blending effect, as you can see at right in Figure 6.12. Ironically, when no spherical aberration is present at all, the discs are a uniform shade, which, while better than the doughnut effect, is not as pleasing as the bright center/dark edge rendition. The shape of the disc also comes into play, with round smooth circles considered the best, and nonagonal or some other polygon (determined by the shape of the lens diaphragm) considered less desirable.

Figure 6.12 Bokeh is less pleasing when the discs are prominent (left), and less obtrusive when they blend into the background (right).

If you plan to use selective focus a lot, you should investigate the bokeh characteristics of a lens before you buy. Canon user groups and forums will usually be full of comments and questions about bokeh, so the research is easy.