How far we’ve come! My first professional job was as a reporter/sportswriter/photographer for a daily newspaper (back when a backslash really meant something), and focusing to achieve a sharp image was a manual process accomplished by turning a ring or knob on the camera or lens until, in one’s highly trained professional judgment, the image was satisfactorily in focus. Manual focus was particularly challenging when shooting sports.

Today, modern digital cameras like the EOS 90D can identify potential subject matter, lock in on human faces, if present, and automatically focus faster than the blink of an eye. Usually. Of course, sometimes a camera’s AF will zero in on the wrong subject, become confused by background pattern, or be totally unable to follow a fast-moving target like a bird in flight. While autofocus has come a long way in the last 30-plus years, it’s still a work-in-progress that relies heavily on input from the photographer. Your Canon EOS 90D can calculate and set focus for you quickly and with a high degree of accuracy, but you still need to make a few settings that provide guidance on three Ws of autofocus: what, where, and when. Your decisions in how you apply those choices supplies the fourth W: why. This chapter will provide you with everything you need to put all four to work.

I’ll even tell you when to abandon the autofocus system and turn to the ancient art of manual focus, too. I’m going to concentrate on what Canon calls “viewfinder shooting,” which is probably the mode most of us use most frequently to capture our still photos. However, I’ll also explain Dual Pixel CMOS AF, which is how the 90D achieves focus in Live View and Movie modes.

How Focus Works

This section describes the differences between contrast detection and phase detection autofocus, and details how linear and cross-type AF sensors work in the 90D’s advanced focusing system. Even those who are familiar with these concepts should still read this section carefully, because Canon has made some revolutionary changes in AF with the introduction of its Dual Pixel CMOS AF sensor design in which every single pixel used for autofocus is split into two photodiodes that can be used to provide advanced autofocus features in Live View and Movie modes.

Simply put, focus is the process of adjusting the camera so that parts of our subject that we want to be sharp and clear are, in fact, sharp and clear. We allow the camera to focus for us, automatically, or we can rotate the lens’s focus ring manually to achieve the desired focus. Manual focusing is especially problematic because our eyes and brains have poor memory for correct focus. That’s why your eye doctor conducting a refraction test must shift back and forth between pairs of lenses and ask, “Does that look sharper—or was it sharper before?” in determining your correct prescription. Too often, the slight differences are such that the lens pairs must be swapped multiple times.

Similarly, manual focusing involves jogging the focus ring back and forth as you go from almost in focus, to sharp focus, to almost focused again. The little clockwise and counterclockwise arcs decrease in size until you’ve zeroed in on the point of correct focus. What you’re looking for is the image with the most contrast between the edges of elements in the image.

The Canon 90D’s autofocus mechanism, like all such systems found in modern cameras, also evaluates these increases and decreases in sharpness, but it is able to remember the progression perfectly, so that autofocus can lock in much more quickly and, with an image that has sufficient contrast, more precisely. Unfortunately, while the camera’s focus system finds it easy to measure degrees of apparent focus at each of the focus points in the viewfinder, it doesn’t really know with any certainty which object should be in sharpest focus. Is it the closest object? The subject in the center? Something lurking behind the closest subject? A person standing over at the side of the picture? Using autofocus effectively involves telling the 90D exactly what it should be focusing on.

Learning to use the 90D’s modern autofocus system is easy, but you do need to fully understand how the system works to get the most benefit from it. Once you’re comfortable with autofocus, you’ll know when it’s appropriate to use the manual focus option, too.

As the camera collects focus information from the sensors, it then evaluates it to determine whether the desired sharp focus has been achieved. The calculations may include whether the subject is moving, and whether the camera needs to “predict” where the subject will be when the shutter release button is fully depressed, and the picture is taken. The speed with which the camera can evaluate focus and then move the lens elements into the proper position to achieve the sharpest focus determines how fast the autofocus mechanism is. Although your 90D will almost always focus more quickly than a human eye, there are types of shooting situations where that’s not fast enough. For example, if you’re having problems shooting a sport with many fast-moving players because the 90D’s autofocus system manically follows each moving subject, a better choice might be to switch Autofocus modes, or shift into Manual and prefocus on a spot where you anticipate the action will be, such as a goal line or soccer net.

Autofocus is generally achieved using two different technologies called contrast detection autofocus (CDAF) and phase detection autofocus (PDAF). I’m going to provide a quick overview of contrast detection first, and then devote much of the rest of this chapter to the complexities of the phase detection system used in the 90D both when framing through the optical viewfinder, and when focusing in Live View and Movie modes.

Contrast Detection

Contrast detection is a slower mode—even though it is inherently a highly accurate method—and was used exclusively by Canon dSLRs in Live View and Movie modes until 2013. That’s when Canon added a small number of special pixels to the sensor of a predecessor of your 90D, the Canon EOS 70D. That camera had pixels embedded in its sensor that allowed a limited type of phase detection autofocus. The Dual Pixel CMOS AF used by the Canon 90D goes much further, as I’ll explain later in this chapter. To appreciate that innovation, you need to understand traditional contrast detection first.

The relatively slow contrast detection method was necessary because, to allow live viewing of the sensor image, the camera’s mirror has to be flipped up out of the way so that the illumination from the lens can continue through the open shutter to the sensor. Your view through the viewfinder is obstructed, of course, and there is no partially silvered mirror to reflect some light down to the autofocus sensors. So, an alternate means of autofocus had to be used in Live View, and that method is contrast detection.

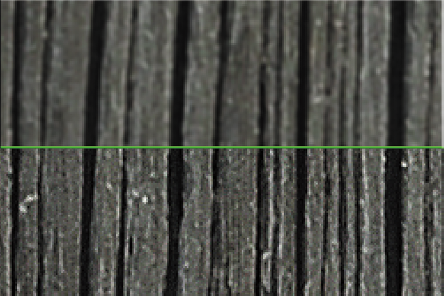

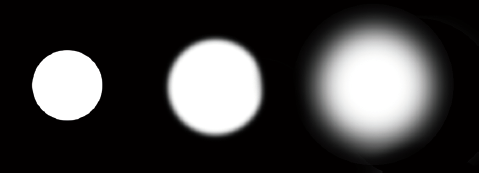

Contrast detection is a bit easier to understand and is illustrated by Figure 5.1, which uses an extreme enlargement of a shot of some wood siding (actually a 19th century outhouse). At top in the figure, the transitions between pixels are soft and blurred. When the image is brought into focus (bottom), the transitions are sharp and clear. Although this example is a bit exaggerated so you can see the results on the printed page, it’s easy to understand that when maximum contrast in a subject is achieved, it can be deemed to be in sharp focus.

Figure 5.1 Focus in contrast detection mode evaluates the increase in contrast in the edges of subjects, starting with a blurry image (top) and producing a sharp, contrasty image (bottom).

As I noted, contrast detection is used in Live View and Movie mode, even when Dual Pixel CMOS AF is also active. (In effect, you get two AF systems from one sensor.) Contrast detection works best and is very accurate with static subjects, but it is inherently slower and not well suited for tracking moving objects. Contrast detection works less well than phase detection in dim and diffuse light because its accuracy is determined by its ability to detect variations in brightness and contrast. You’ll find that contrast detection works better with faster lenses, too, because larger lens openings admit more light that can be used by the sensor to measure contrast. Although achieving focus with contrast detection is generally quite a bit slower, there are several advantages—and disadvantages—to this method:

- Works with more image types. Any subject that has edges will work with CDAF.

- Focus on any point. With contrast detection, any portion of the image can be used to focus: you don’t need dedicated AF sensors. Focus is achieved with the actual sensor image, so focus point selection is simply a matter of choosing which part of the sensor image to use. It’s easy to move the focus frame around to virtually any location.

- Potentially more accurate. Contrast detection is clear-cut. The camera can clearly see when the highest contrast has been achieved, as long as there is sufficient light to allow the camera to examine the image produced by the sensor. However, some “hunting” may be necessary. As the camera seeks the ideal plane of focus, it may overshoot and have to back up a little, then recorrect if the new focus plane is not optimal. Hunting can be frustrating for the photographer because you’re watching the focus change visually in real time. However, once CDAF settles on the ideal focus plane, the results are generally accurate.

Phase Detection

Like all digital SLRs that use an optical viewfinder and mirror system to preview an image (that is, when not in Live View mode), the Canon EOS 90D calculates focus using what is called a passive phase detection system. It’s passive in the sense that the ambient illumination in a scene (or that illumination augmented with a focus-assist beam) is used to determine correct focus.

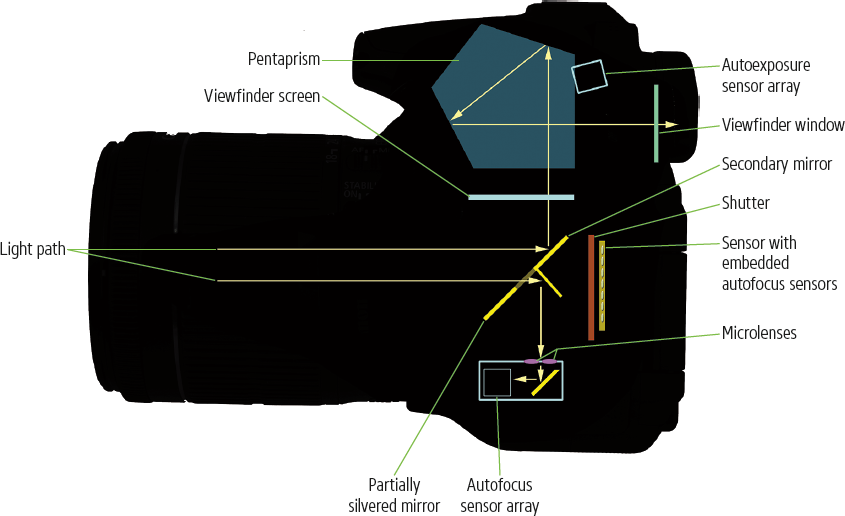

Parts of the image from two opposite sides of the lens are directed through a partially silvered area in the mirror, down to the floor of the camera’s mirror box, where an autofocus sensor array resides; the rest of the illumination from the lens bounces upward toward the optical viewfinder system and the autoexposure sensors. Figure 5.2 is a wildly over-simplified illustration that may help you visualize what is happening.

SIMPLIFICATION MADE OVERLY SIMPLE

To reduce the complexity of the diagram, it doesn’t show the actual path of the light passing through the lens, as it converges to the point of focus. That point is either the viewfinder screen when the mirror is down or the sensor plane when the mirror is flipped up and the shutter has opened. Nor does it show the path of the light directed to the autoexposure sensor. Only two of the pairs of autofocus microlenses are shown, and they are greatly enlarged so you can see their approximate position. All we’re concerned about here is how light reaches the autofocus sensor.

As light emerges from the rear element of the lens, most of it is reflected upward toward the focusing screen, where the relative sharp focus (or lack of it) is displayed (and which can be used to evaluate manual focus). It then bounces off two more reflective surfaces in the pentaprism (in the 90D; other cameras may use a less expensive and less bright pentamirror system instead) emerging at the optical viewfinder correctly oriented left/right and up/down. (The image emerges from the lens reversed.) Some of the illumination is directed to the autoexposure sensor at the top of the pentaprism housing.

Figure 5.2 Part of the light is bounced downward to the autofocus sensor array and split into two images, which are compared and aligned to create a sharply focused image.

A small portion of the illumination passes through that partially silvered center of the main mirror, and is directed downward to the autofocus sensor array, which includes 45 separate autofocus “detectors.” Conceptually, these function as shown in Figure 5.3, another simplified illustration. The illumination arrives from opposite sides of the lens surface and is directed through separate microlenses, producing two half images. These images are compared with each other, much like (actually, exactly like) a two-window rangefinder used in surveying, weaponry, and non-SLR cameras like the venerable Leica M film models.

When the image is out of focus—or out of phase—as in Figure 5.4 (top), the two halves, each representing a slightly different view from opposite sides of the lens, don’t line up. Sharp focus is achieved when the images are “in phase,” and aligned, as in Figure 5.4 (bottom).

Figure 5.3 In phase detection, parts of an image are split in two and compared.

Figure 5.4 When the image is in focus, the two halves of the image align, as with a rangefinder.

This process tells the camera when the image pair are “in phase” and aligned. The rangefinder approach of phase detection tells the 90D exactly how out of focus the image is, and in which direction (focus is too near, or too far) thanks to the amount and direction of the displacement of the split image. The camera can quickly and precisely snap the image into sharp focus and match the lines.

As with any rangefinder-like function, accuracy is better when the “base length” between the two images is larger. (Think back to your high school trigonometry; you could calculate a distance more accurately when the separation between the two points where the angles were measured was greater.) For that reason, phase detection autofocus is more accurate with larger (wider) lens openings than with smaller lens openings and may not work at all when the f/stop is smaller than f/5.6 or f/8. Obviously, the “opposite” edges of the lens opening are farther apart with a lens having an f/2.8 maximum aperture than with one that has a smaller, f/5.6 maximum f/stop, and the base line is much longer. The 90D can perform these comparisons and then move the lens elements directly to the point of correct focus very quickly, in milliseconds.

Unfortunately, while the 90D’s focus system finds it easy to measure degrees of apparent focus at each of the focus points in the viewfinder, it doesn’t really know with any certainty which object should be in sharpest focus. Is it the closest object? The subject in the center? Something lurking behind the closest subject? A person standing over at the side of the picture? Many of the techniques for using autofocus effectively involve telling the EOS 90D exactly what it should be focusing on, by choosing a focus zone or by allowing the camera to choose a focus zone for you. I’ll address that topic shortly.

Dual Pixel CMOS AF

So far, we’ve explored how the 90D autofocuses with phase detection when using the optical view-finder. I’ll tell you more about autofocus in “viewfinder” photography shortly. However, a completely different AF system comes into play when you’re capturing stills or movies in live view. Understanding contrast and phase detection helps you appreciate the technology of Canon’s Dual Pixel CMOS AF system. Used in Live View mode while shooting stills and movies, it works much more quickly than the camera’s more traditional contrast detection system alone.

An array of special pixels, which cover 88 percent of the frame horizontally and virtually 100 percent vertically, provide the same type of split-image rangefinder phase detection AF that is available when using the optical viewfinder. The most important aspect of the system is that it doesn’t rob the camera of any imaging resolution. It would have been possible to place AF sensors between the pixels used to capture the image, but that would leave the sensor with less area with which to capture light. Keep in mind that CMOS sensors, unlike earlier CCD sensors, have more on-board circuitry which already consumes some of the light-gathering area. Microlenses are placed above each photosensitive site to focus incoming illumination on the sensor and to correct for the oblique angles from which some photons may approach the imager. (Older lenses, designed for film, are the worst offenders in terms of emitting light at severely oblique angles; newer “digital” lenses do a better job of directing photons onto the sensor plane with a less “slanted” approach.)

With the Dual Pixel CMOS AF system, the same photosites capture both image and autofocus information. Each pixel is divided into two photodiodes, facing left and right when the camera is held in horizontal orientation (or above and below each other in vertical orientation; either works fine for autofocus purposes). Each pair functions as a separate AF sensor, allowing a special integrated circuit to process the raw autofocus information before sending it on to the 90D’s digital image processor, which handles both AF and image capture. For the latter, the information grabbed by both photodiodes is combined, so that the full photosensitive area of the sensor pixel is used to capture the image.

The double-duty pixels are allocated to 143 different zones within the frame and can be used with Face+Tracking, Spot AF, 1-Point AF, and Zone AF area modes. When you’ve chosen the 1-Point AF mode, you can use the directional controls to move the focus area in tiny increments to any of 5,481 different points of the sensor. Those points don’t represent actual dual pixels but, rather, the regions you can specify as the current “focus” of the autofocus system (so to speak).

While traditional contrast detection frequently involves frustrating “hunting” as the camera continually readjusts the focus plane trying to find the position of maximum contrast, adding Dual Pixel CMOS AF phase detection allows the 90D to focus smoothly, which is important for speed, and especially essential when shooting movies (where all that hunting is unfortunately captured for posterity). Movie Servo AF tracking is improved, allowing shooting movies of subjects in motion. The system works with (at this writing) more than 100 different lenses, both current and previously available optics, and works especially well with lenses that have speedy USM or STM motors. I’ll explain the 90D’s AF operation in live view and movie shooting in more detail in Chapter 10.

Cross-Type Focus Point

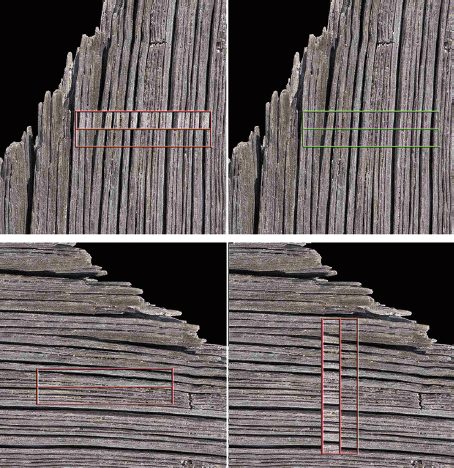

Returning to the optical viewfinder’s AF system, we’re going to explore one special aspect next. So far, we’ve only looked at focus sensors that calculate focus in a single direction. Figure 5.5 (top left and right) illustrates a horizontally oriented linear focus sensor evaluating a subject that is made up, predominantly, of vertical lines. But what does such a sensor do when it encounters a subject that isn’t conveniently aligned at right angles to the sensor array? You can see the problem in Figure 5.5 (bottom left), which pictures the same weathered wood siding rotated 90 degrees. The horizontal grain of the wood isn’t divided as neatly by the split image, so focusing using phase detection is more difficult. The lines in the grain don’t cross the AF sensor at right angles anymore.

Figure 5.5 A horizontally oriented sensor handles vertical lines easily (top). A horizontal sensor has problems with subjects that have parallel horizontal lines (bottom left). A vertically oriented sensor is really needed for that type of subject (bottom right).

You can see the “solution” at bottom right in Figure 5.5, in the form of a vertical linear sensor, which does a better job of interpreting horizontal lines. By mixing both types in a focusing system, the vertical sensors could detect differences in horizontal lines, while the horizontal sensors took care of the vertical lines. Both varieties are equally adept at handling diagonal lines, which crossed each type of line sensor at a 45-degree angle.

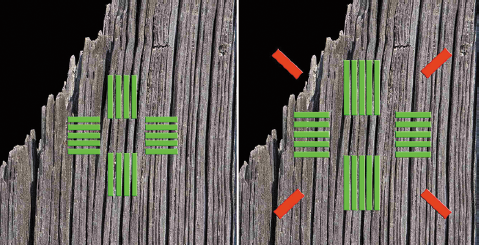

However, a better solution is the use of a cross-type sensor, which is a merger of vertical and horizontal linear sensors, thus including sensitivity to horizontal, vertical, and lines at any diagonal angle. In lower light levels, with subjects that are moving, or with subjects that have no pattern and less contrast to begin with, the cross-type sensor not only works faster but can focus subjects that a horizontal- or vertical-only sensor can’t handle at all.

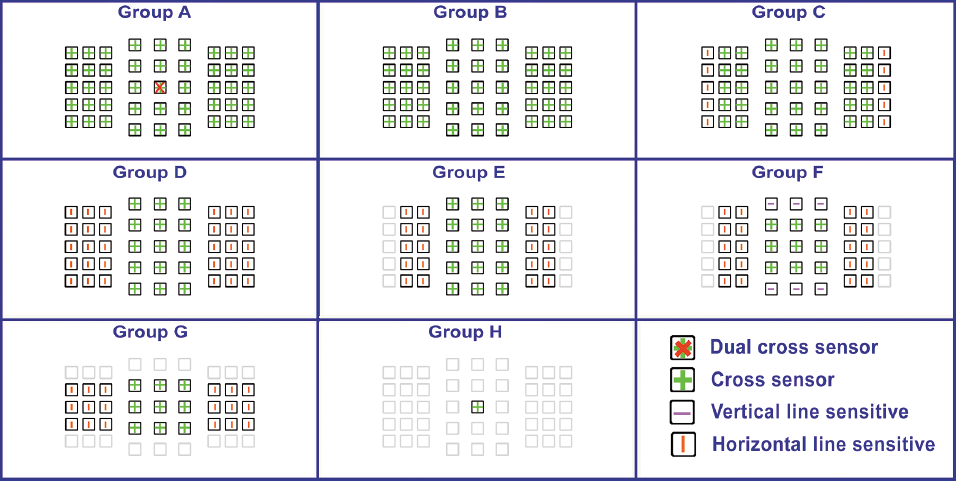

In practice, these sensors consist of an array of lines and, in the 90D, none of them are strictly horizontal or vertical in orientation. Instead, the AF points are arranged as shown at left in Figure 5.6, using what are called cross-type sensors that form a plus-sign shape. All 45 AF points in the 90D are potentially cross sensors. The number available will depend on the aspect ratio you select, which can “crop out” some of the sensors, and the lens mounted on your camera (some AF points cannot function in cross mode with certain lenses, as I’ll explain shortly). All 45 AF sensors function with lenses that have a maximum aperture of f/5.6 or larger (remember that smaller numbers equal larger apertures; f/4 is larger than f/5.6, for example). So, if you’re using a lens with an f/stop from, say, f/1.2 through f/5.6, all 45 AF points will function as cross-type sensors. (Some may function in cross mode with a few f/8 lenses.) If your maximum aperture is even larger—f/2.8 or greater—the center AF point will also use a pair of diagonal sensors, represented in red at right in Figure 5.6. Note that the baseline of these diagonal AF points is much larger than that of the green vertically/horizontally oriented sensors. Coupled with the larger baseline of lenses with, say, f/1.2 to f/2.8 maximum apertures, the center AF sensors are significantly more accurate than those at the other 44 locations in the frame.

Figure 5.6 Cross-type sensors can achieve sharp focus with horizontal, vertical, and diagonal lines (left). The center focus point (right) has additional diagonal sensors (in red) that function with lenses with an f/2.8 or larger maximum aperture.

Usable AF Points and Lens Groups

The 45 AF points in your camera all function as cross-type sensors with the majority of lenses that you are likely to own. However, if you are using certain slower lenses, or use a teleconverter to multiply your lens’s focal length, some of the focus points revert to line sensor behavior or may become totally unavailable for autofocus.

Canon makes sorting out how usable AF points are affected by your choice of lenses and lens+extender combinations easy, by classifying them in groups, labeled A through H. Pages 7 to 11 of Canon’s 90D Supplemental Information PDF can be downloaded from Canon’s website. It lists the lenses available at the time the 90D was introduced and assigns a group to each. If you own lenses introduced since then, I urge you to visit the Canon website for the definitive group for your optics.

The lens and lens/teleconverter combinations in the Group A and Group B categories allow all 45 AF points to function as cross-type sensors, with Group A entries enabling the dual-cross center focus point. With Group C and Group D lenses, some or all the AF points at the left and right flanks of the center array revert to horizontal line sensitive behavior. With Group E and Group F lenses, the two groups of five points at the far left and right edges of the array are not available, and Group G lens combinations disable the upper and lower row of points, leaving only 27 usable AF points. Group G lenses allow only one cross-type point in the center of the array.

Figure 5.7 provides a quick reference to the function of each AF sensor within a given lens grouping. Dual cross, cross-type, horizontal, and vertical sensors are all represented. If an AF point is grayed out in a group, that sensor is not used and is not displayed as you shoot. When you press either AF point selection button, the disabled points will blink, while the enabled points will stay lit. Here’s a more detailed listing of the AF point behaviors you can expect:

- Group A. Autofocusing with all 45 points is possible, so you can choose any of the AF area selection modes (described later in this chapter). However, with all lenses in this group, the center AF point functions as a high-precision dual cross sensor if that lens has a maximum aperture of f/2.8 or larger. The other 44 AF points are cross-type sensors. (See Figure 5.7, upper left.)

- Group B. This group of lens/lens+extender combinations is virtually identical in function to Group A, except that the center AF point serves as a conventional cross-type sensor, rather than a dual cross sensor. Autofocusing with all 45 points is possible. (See Figure 5.7, upper center.)

- Group C. This group of lens/lens+extender combinations uses all 45 AF points, but the outermost 5 sensors on each side are sensitive only to horizontal lines, as you can see represented by orange lines in Figure 5.7, upper right.

Figure 5.7 Dual cross, cross-type, horizontal, and vertical sensors.

- Group D. This fourth group uses all 45 AF points like the previous three, but only the 15 points in the center function as cross-type sensors. The outer sensors all are sensitive only to horizontal lines. (See Figure 5.7, center left.)

- Group E. Only 35 AF points are used with this group of lens/lens+extender combinations. The center 15 function as cross-type sensors, while two columns of sensors on either side of the center (20 in all) are sensitive only to horizontal lines. (See Figure 5.7, center.)

- Group F. Just 35 AF points are available with this next group of lens/lens+extender combinations. Only the 9 sensors at the very center are of the cross type. The rows above and below the center are sensitive to vertical lines, while the two columns on either side of the center are sensitive to horizontal lines. (See Figure 5.7, center right.)

- Group G. Only 27 AF points are available with this group. The nine center points function as cross-type sensors; the nine points to the left and nine to the right are sensitive to horizontal lines. The other points are disabled. (See Figure 5.7, lower left.)

- Group H. Only the center cross-type focus point can be used. (See Figure 5.7, bottom center.)

Focus Modes

Focus modes tell the camera when to evaluate and lock in focus. They don’t determine where focus should be checked; that’s the function of other autofocus features. Focus modes tell the camera whether to lock in focus once, say, when you press the shutter release halfway (or use some other control, such as the AF-ON button), or whether, once activated, the camera should continue tracking your subject and, if it’s moving, adjust focus to follow it.

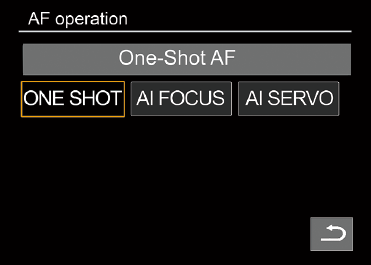

The 90D has three AF modes: One-Shot AF (also known as single autofocus), AI Servo (continuous autofocus), and AI Focus AF (which switches between the two as appropriate). I’ll explain all of these in more detail later in this section. But first, some confusion . . .

MANUAL FOCUS

With manual focus activated by sliding the AF/MF switch on the lens, your 90D lets you set the focus yourself. There are some advantages and disadvantages to this approach. While your batteries will last longer in manual focus mode, it will take you longer to focus the camera for each photo, a process that can be difficult. Modern digital cameras, even dSLRs, depend so much on autofocus that the viewfinders are no longer designed for optimum manual focus. Pick up any film camera and you’ll see a bigger, brighter viewfinder with a focusing system that’s a joy to focus on manually.

Adding Circles of Confusion

You know that increased depth-of-field brings more of your subject into focus. But more depth-of-field also makes autofocusing (or manual focusing) more difficult because the contrast is lower between objects at different distances. This is an added factor beyond the rangefinder aspects of lens opening size in phase detection. An image that’s dimmer is more difficult to focus with any type of focus system, phase detection, contrast detection, or manual focus.

So, focus with a 200mm lens (or zoom setting) may be easier in some respects than at a 28mm focal length (or zoom setting) because the longer lens has less apparent depth-of-field. By the same token, a lens with a maximum aperture of f/1.8 will be easier to autofocus (or manually focus) than one of the same focal length with an f/4 maximum aperture, because the f/4 lens has more depth-of-field and a dimmer view. That’s yet another reason why lenses with a maximum aperture smaller than f/5.6 can give your 90D’s autofocus system fits—increased depth-of-field joins forces with a dimmer image that’s more difficult to focus using phase detection.

To make things even more complicated, many subjects aren’t polite enough to remain still. They move around in the frame, so that even if the 90D is sharply focused on your main subject, it may change position and require refocusing. An intervening subject may pop into the frame and pass between you and the subject you meant to photograph. You (or the 90D) have to decide whether to lock focus on this new subject or remain focused on the original subject. Finally, there are some kinds of subjects that are difficult to bring into sharp focus because they lack enough contrast to allow the 90D’s AF system (or our eyes) to lock in. Blank walls, a clear blue sky, or other subject matter may make focusing difficult.

If you find all these focus factors confusing, you’re on the right track. Focus is, in fact, measured using something called a circle of confusion. An ideal image consists of zillions of tiny little points, which, like all points, theoretically have no height or width. There is perfect contrast between the point and its surroundings. You can think of each point as a pinpoint of light in a darkened room. When a given point is out of focus, its edges decrease in contrast and it changes from a perfect point to a tiny disc with blurry edges (remember, blur is the lack of contrast between boundaries in an image). (See Figure 5.8.)

Figure 5.8 When a pinpoint of light (left) goes out of focus, its blurry edges form a circle of confusion (center and right).

If this blurry disc—the circle of confusion—is small enough, our eye still perceives it as a point. It’s only when the disc grows large enough that we can see it as a blur rather than a sharp point that a given point is viewed as out of focus. You can see, then, that enlarging an image, either by displaying it larger on your computer monitor or by making a large print, also enlarges the size of each circle of confusion. Moving closer to the image does the same thing. So, parts of an image that may look perfectly sharp in a 5 × 7–inch print viewed at arm’s length, might appear blurry when blown up to 11 × 14 and examined at the same distance. Take a few steps back, however, and it may look sharp again.

To a lesser extent, the viewer also affects the apparent size of these circles of confusion. Some people see details better at a given distance and may perceive smaller circles of confusion than someone standing next to them. For the most part, however, such differences are small. Truly blurry images will look blurry to just about everyone under the same conditions.

Technically, there is just one plane within your picture area, parallel to the back of the camera (or sensor, in the case of a digital camera), that is in sharp focus. That’s the plane in which the points of the image are rendered as precise points. At every other plane in front of or behind the focus plane, the points show up as discs that range from slightly blurry to extremely blurry until the out-of-focus areas become one large blur that de-emphasizes the background.

In practice, the discs in many of these planes will still be so small that we see them as points, and that’s where we get depth-of-field. Depth-of-field is just the range of planes that include discs that we perceive as points rather than blurred splotches. The size of this range increases as the aperture is reduced in size and is allocated roughly one-third in front of the plane of sharpest focus and two-thirds behind it. The range of sharp focus is always greater behind your subject than in front of it.

Your Autofocus Mode Options

Choosing the right autofocus mode and the way in which focus points are selected is your key to success. Using the wrong mode for a particular type of photography can lead to a series of pictures that are all sharply focused—on the wrong subject. When I first started shooting sports with an autofocus SLR (back in the film camera days), I covered one game alternating between shots of base runners and outfielders with pictures of a promising young pitcher, all from a position next to the third-base dugout. The base runner and outfielder photos were great because their backgrounds didn’t distract the autofocus mechanism. But all my photos of the pitcher had the focus tightly zeroed in on the fans in the stands behind him. Because I was shooting film instead of a digital camera, I didn’t know about my gaffe until the film was developed. A simple change, such as locking in focus or focus zone manually, or even manually focusing, would have done the trick.

To save battery power, unless Continuous Autofocus is activated, your 90D doesn’t start to focus the lens until you partially depress the shutter release or AF-ON button. But autofocus isn’t some mindless beast out there snapping your pictures in and out of focus with no feedback from you after you press that button. There are several settings you can modify that return at least a modicum of control to you. Your first decision should be whether you set the 90D to One-Shot, AI Servo AF, or AI Focus AF. With the camera set for one of the Creative Zone modes, press the AF button on the top panel and use the Main Dial or QCD to select the focus mode you want (see Figure 5.9). Press SET to confirm your choice. (The AF/M switch on the lens must be set to AF before you can change autofocus mode.)

Figure 5.9 Press the AF button and then rotate the Main Dial or Quick Control Dial until the AF choice you want is selected.

One-Shot AF

In this mode, also called single autofocus, focus is set once and remains at that setting until the button is fully depressed, taking the picture, or until you release the shutter button without taking a shot. For non-action photography, this setting is usually your best choice, as it minimizes out-of-focus pictures (at the expense of spontaneity). The drawback here is that you might not be able to take a picture at all while the camera is seeking focus; you’re locked out until the autofocus mechanism is happy with the current setting. One-Shot AF/Single Autofocus is sometimes referred to as focus priority for that reason. Because of the small delay while the camera zeroes in on correct focus, you might experience slightly more shutter lag. This mode uses less battery power.

When sharp focus is achieved, the selected focus point will flash red in the viewfinder, and the focus confirmation light at the lower right will illuminate and remain lit as long as focus is maintained and you continue to hold down the shutter release. The exposure will be locked at the same time. By keeping the shutter button depressed halfway, you’ll find you can reframe the image while retaining the focus (and exposure) that’s been set. You can also use the AE lock/FE lock button to retain the exposure calculated from the center AF point while reframing.

AI Servo AF

This mode, also known as continuous autofocus, is the mode to use for sports and other fast-moving subjects. In this mode, once the shutter release is partially depressed, the camera sets the focus but continues to monitor the subject, so that if it moves or you move, the lens will be refocused to suit. Focus and exposure aren’t really locked until you press the shutter release down all the way to take the picture. You’ll often see continuous autofocus referred to as release priority. If you press the shutter release down all the way while the system is refining focus, the camera will go ahead and take a picture, even if the image is slightly out of focus. You’ll find that AI Servo AF produces the least amount of shutter lag of any autofocus mode: press the button and the camera fires. It also uses the most battery power, because the autofocus system operates as long as the shutter release button is partially depressed. With C.Fn II-4 and C.Fn II-5 you can specify autofocus priority separately for the first and subsequent shots in a continuous sequence, giving priority to shooting speed, best focus, or equal weight, as explained in Chapter 9.

AI Servo AF uses a technology called predictive AF, which allows the 90D to calculate the correct focus if the subject is moving toward or away from the camera at a constant rate. It uses either the automatically selected AF point or the point you select manually to set focus.

AI Focus AF

This setting is a combination of the first two. When selected, the camera focuses using One-Shot AF and locks in the focus setting. But, if the subject begins moving, it will switch automatically to AI Servo AF and change the focus to keep the subject sharp. AI Focus AF is a good choice when you’re shooting a mixture of action pictures and less dynamic shots and want to use One-Shot AF when possible. The camera will default to that mode yet switch automatically to AI Servo AF when it would be useful for subjects that might begin moving unexpectedly, such as children or pets.

Manual Focus

With manual focus activated by sliding the AF/MF switch on the lens, your 90D lets you set the focus yourself, both using the eye-level optical viewfinder and on the LCD monitor in Live View mode. There are some advantages and disadvantages to this approach. While your batteries will last longer in manual focus mode through the optical viewfinder, it will take you longer to focus the camera for each photo, a process that can be difficult. Modern digital cameras, even dSLRs, depend so much on autofocus that the viewfinders of models that have less than full-frame-sized sensors are no longer designed for optimum manual focus.

Selecting an AF Area Selection Mode

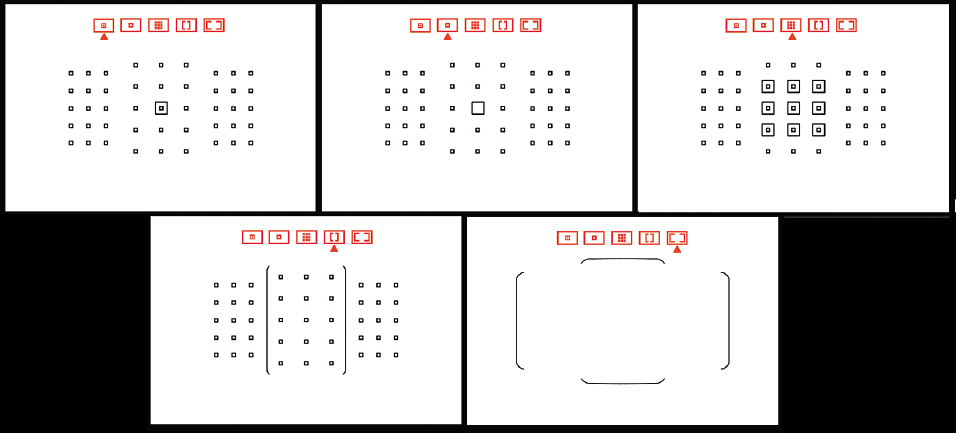

The Canon EOS 90D uses 45 different focus points to calculate correct focus. In any of the Basic Zone shooting modes, the focus point is selected automatically by the camera. In the Creative Zone modes, you can allow the camera to select the focus point automatically, or you can specify which focus point should be used. There are four AF Area Selection modes, plus Automatic Selection. They are shown in Figure 5.10:

- Spot AF (Manual Selection). You can move the small focus point (represented by the smallest boxes shown at upper left in Figure 5.10) to any of the pinpoint zones.

- 1-Point AF (Manual Selection). You can choose one AF point for focus, represented by the larger box in Figure 5.10, upper center.

- Zone AF (Manual Zone Selection). Select any of nine different focus zones, each with a 3 × 3–point array of nine points, illustrated at upper right in Figure 5.10.

- Large Zone AF (Manual Selection of Zone). You can choose the clusters of 15 focus points at left, right, or middle of the focus point array (lower left, Figure 5.10).

- 45-point Automatic Selection AF. The camera will choose the focus point for you. This mode is always used in Basic Zone exposure modes. The focus area used is shown at lower right in the figure.

To choose the AF Area, just follow these steps:

- 1. Make sure the lens AF/MF switch is set to AF.

- 2. Tap the shutter release to activate the focus system.

Figure 5.10 The AF Area Selection modes are Spot AF (Manual Selection), upper left; 1-Point AF (upper center); Zone AF (Manual Zone Selection), upper right; Large Zone AF (Manual Selection of Zone), lower left; and 45-point Automatic Selection AF, lower right.

- 3. Press the AF Area Selection Mode button located northwest of the Main Dial. The current focus selection indicators will be highlighted in red.

- 4. Continue pressing, if necessary, until the method has an up-pointing triangle underneath it in the viewfinder (or is highlighted on the LCD monitor).

As explained in Chapter 9, you can use C.Fn II-8 to limit the AF area selection modes available, and C.Fn II-9 to adjust the controls used to choose the selection mode. When choosing a focus point manually, the viewfinder indicator will display SEL [ ] (for Spot or 1-point selection) or [ ] AF (for the other three modes) at the bottom of the frame.

In the Spot or 1-point manual selection mode, press the focus point selection button (in the upper-right corner of the back of the camera) or the AF Area Selection mode button. Then, use the multi-controller to move the active focus point around the frame. If you press SET, the AF center point will be selected. You can also rotate the Main Dial to move the focus point to the left or right in the middle row of sensors and rotate the QCD to move up and down rows. In zone AF mode, rotating either the Main Dial or Quick Control Dial will switch from zone to zone in a loop.

While automatic point selection works well and is often best for moving subjects, manual point selection can be quite useful when you have time to zero in on a subject. This mode is certainly your best choice when you want to focus precisely on a subject that is surrounded by fine detail, as shown in Figure 5.11. The heron was not moving and my camera and 400mm lens were mounted on a sturdy tripod, so it was easy to place the focus spot exactly where I wanted it. Keep in mind that the portion of the sensor used to autofocus is not precisely represented by the rectangle shown in the viewfinder, so if you’re focusing on, say, the near eye of a portrait subject turned at a 45-degree angle with a wide aperture, you might end up focusing on the bridge of their nose instead. You’ll want to keep the actual focus area in mind in situations where focus is that critical.

Figure 5.11 Manual point selection allowed focusing precisely on the heron, despite the surrounding detail.

AF with Color Tracking

Face and eye detection used to enhance autofocus are all the rage right now, because a hefty percentage of the photos most of us take involve human beings. The greatest leaps forward in this technology have come with mirrorless cameras, like the Canon EOS R, because photos are always composed using the actual sensor image used to take the picture. Every pixel used in a mirrorless sensor can be deployed to look for faces (of any skin tone) and their distinguishing features (such as eyes or mouths) in high resolution. A traditional autofocus sensor for an optical viewfinder that has say, 45 different focus points, is incapable of such precision.

As you might expect, Canon has worked hard to overcome this challenge, and your 90D can deploy powerful color tracking and face detection features when you’re working with the optical view-finder. Moreover, the camera adds even more sophisticated eye detection when using Live View. The key to the optical viewfinder’s color tracking and face detection prowess stems from the new 220,000-pixel RGB+infrared exposure sensor mentioned in Chapter 4. The color information gathered by the exposure sensor is shared with the 90D’s AF system to enhance autofocus by helping the camera identify what kinds of subjects are within the frame. For example, the color data acquired can recognize colors equivalent to skin tones, and thus enhance AF sensitivity when shooting still photos of human subjects. (Eye detection, however, still requires the sensor-based precision of Live View.)

To use this function for viewfinder shooting, your AF area selection mode should be set to Zone AF (Manual Selection), Large Zone AF (Manual Selection), or Automatic Selection AF (the camera selects). You can activate color tracking/face detection for those AF area modes using C.Fn II-12: Auto AF Point Selection: EOS iTR AF, as described in Chapter 9. There are three options:

- 0: EOS iTR AF (Face Priority). In either Zone AF mode or Automatic Selection mode, the camera will give the highest priority to face detection but will focus on other subjects if no faces are found. Once focus is achieved, the 90D continues to focus on any faces that were initially in sharp focus, even if they move around within the frame. It does an excellent job of tracking human subjects. Focusing will take slightly longer than if face detection were disabled.

- 1: Enable. In either Zone AF or Automatic Selection mode, the camera tries to focus on faces recognized, or on the nearest subject if no faces are found. Once focus is achieved, autofocus tracks using the color of the area initially focused on. Again, focusing takes slightly longer than if you had chosen 2: Disable, described next.

- 2: Disable. No color or face information is used for autofocus. AF points are selected using only the information from the 45-point autofocus system.

Color tracking works well in One-Shot mode to lock in focus; in AI Servo AF mode, focusing on humans is enhanced (if no skin tones are detected, the camera will focus on the nearest object). As AI Servo AF continues to refocus as required until the shutter release is pressed down all the way, the 90D continues to select focus points representing the colors of the subject first focused on. Under lighting conditions dim enough to trigger the AF-assist beam, color information is not used.

Other Important AF Parameters

To this point, I’ve covered the most essential components of autofocus during viewfinder shooting with the 90D. There are several other parameters used to fine-tune the 90D’s AF behavior, all found under the Custom Functions II menu. Some are minor tweaks, enabling you, for example, to specify whether AF points are shown in red in the viewfinder after focus is achieved. I’m going to list them next, and you can check Chapter 9 for instructions on how to select the options available with each of these additional features.

- Tracking Sensitivity (C.Fn II-1). This option determines how quickly the 90D stops tracking the original subject and switches to a new one that intervenes in the frame.

- Acceleration/Deceleration Tracking (C.Fn II-2). Use this to set tracking sensitivity for subjects that change speed significantly or start or stop suddenly.

- AF Point Auto Switching (C.Fn II-3). Use this to set the sensitivity of AF point switching when a subject moves quickly away from or toward the camera, or in the up/down/left/right directions.

- AI Servo 1st Image Priority (C.Fn II-4). This option sets focus priority, release priority, or balance priority for the first shot in a sequence when AI Servo AF is active.

- AI Servo 2nd Image Priority (C.Fn II-5). Use this option to set focus priority, release priority, or balance priority for the subsequent images when shooting continuously when AI Servo AF is active.

- Lens Drive When AF Impossible (C.Fn II-6). If the 90D is having difficulty achieving focus, this setting tells the camera either to stop or continue.

- Select AF Area Selection Mode (C.Fn II-7). This setting allows you to enable or disable Zone AF, Large Zone AF, or Auto Section AF for viewfinder shooting. (1-Point AF cannot be disabled.)

- Limit AF Methods (C.Fn II-8). If you find you seldom use one or more AF Methods in Live View, you can hide any or all of them except for 1-Point AF using this setting.

- AF Area Selection Method (C.Fn II-9). This option allows you to choose the AF Area Selection control—either presses of the AF selection/AF area selection buttons or a single press of those buttons followed by rotation of the Main Dial.

- Orientation Linked AF Point (C.Fn II-10). Use this option to specify using the same AF point in vertical and horizontal orientations, or choose separate area modes and points, or separate points only when holding the camera in vertical or horizontal positions.

- Initial Servo AF Point (C.Fn II-11). This allows you to determine the initial AF point when AF area selection mode is set to 45-point AF (Auto Selection).

- Auto AF point Selection: EOS iTR AF (C.Fn II-12). This entry activates or deactivates face detection using color information during autofocus, described earlier in the AF with Color Tracking section.

- AF Point Selection Movement (C.Fn II-13). When manually selecting a point, you can choose whether the point selection stops at the edges of the frame or wraps around to the opposite edge.

- AF Point Display During Focus (Viewfinder Shooting) (C.Fn II-14). Use this setting to choose which AF points are displayed during focus.

- Viewfinder Display Illumination (C.Fn II-15). Use this option to select whether AF points in the view-finder are illuminated in red once focus is achieved.

- AF Microadjustment (C.Fn II-16). Use this to adjust the viewfinder AF system to correct front/back focus problems. I’ll detail how to use this feature later in this chapter.

Back-Button Focus

Once you’ve been using your camera for a while, you’ll invariably encounter the terms back focus and back-button focus and wonder if they are good things or bad things. Actually, they are two different things, and are often confused with each other. Back focus is a bad thing and occurs when a lens consistently autofocuses on a plane that’s behind your desired subject. This malady may be found in some of your lenses, or all your optics may be free of the defect. The good news is that if the problem lies in a particular lens (rather than a camera misadjustment that applies to all your lenses), it can be fixed. I’ll show you how to do that using the AF Microadjustment feature later in this chapter.

Back-button focus, on the other hand, is a tool you can use to separate two functions that are commonly locked together—exposure and autofocus—so that you can lock in exposure while allowing focus to be attained at a later point, or vice versa. It’s a good thing, although using back-button focus effectively may require you to unlearn some habits and acquire new ways of coordinating the action of your fingers.

As you have learned, the default behavior of your Canon 90D is to set both exposure and focus (when AF is active) when you press the shutter release down halfway. When using One-Shot mode, that’s that: both exposure and focus are locked and will not change until you release the shutter button, or press it all the way down to take a picture and then release it for the next shot. In AI Servo mode, exposure is locked and focus is set when you press the shutter release halfway, but the camera will continue to refocus if your subject moves for as long as you hold down the shutter button halfway. Focus isn’t locked until you press the button down all the way to take the picture. In AI Focus AF mode, the camera will start out in One-Shot mode, but switch to AI Servo AF if your subject begins moving.

What back-button focus does is decouple or separate the two actions. You can retain the exposure lock feature when the shutter is pressed halfway but assign autofocus start and/or autofocus lock to a different button. So, in practice, you can press the shutter button halfway, locking exposure, and reframe the image if you like (perhaps you’re photographing a backlit subject and want to lock in exposure on the foreground, and then reframe to include a very bright background as well).

But, in this same scenario, you don’t want autofocus locked at the same time. Indeed, you may not want to start AF until you’re good and ready, say, at a sports venue as you wait for a ballplayer to streak into view in your viewfinder. With back-button focus, you can lock exposure on the spot where you expect the athlete to be and activate AF the moment your subject appears. The 90D gives you a great deal of flexibility, both in the choice of which button to use for AF, and the behavior of that button. You can start autofocus, lock autofocus at a button press, or lock it while holding the button. That’s where the learning of new habits and mind-finger coordination comes in. You need to learn which back-button focus techniques work for you, and when to use them.

Back-button focus lets you avoid the need to switch from One-Shot to AI Servo AF when your subject begins moving unexpectedly. Nor do you need to use AI Focus AF mode and hope the camera switches from One-Shot to AI Servo appropriately. You retain complete control. It’s great for sports photography when you want to activate autofocus precisely based on the action in front of you. It also works for static shots. You can press and release your designated focus button, and then take a series of shots using the same focus point. Focus will not change until you once again press your defined back button.

Want to focus on a spot that doesn’t reside under one of the camera’s 45 focus areas? Use back-button focus to zero in focus on that location, then reframe. Focus will not change. Don’t want to miss an important shot at a wedding or a photojournalism assignment? With back-button focus, you can focus first, and wait until the decisive moment to press the shutter release and take your picture. The 90D will respond immediately and not bother with refocusing at all.

Back-button focus can also save battery power. Ordinarily, your IS lens will begin adjusting for camera shake as soon as you begin focusing. Constantly refocusing can consume a lot of power. With back-button focus, the IS isn’t switched on until you decide to autofocus on your subject.

Activating Back-Button Focus

You’ll find the key control for enabling back-button focus at the very bottom of the C.Fn III-4 Custom Controls entry. Just follow these steps:

- 1. Access Custom Functions. Press the MENU button and use the Main Dial to navigate to the Custom Function menus, located between the Set-up (wrench icon) and My Menu (star icon) tabs.

- 2. Select C.Fn III: Operation/Others. Press SET.

- 3. Navigate to C.Fn III-3: Custom Controls. Press SET.

- 4. Highlight the top entry in the left-most column, “Shutter Butt. Half-Press” and press SET.

- 5. Set Shutter Button to Metering Start. A screen will appear with three choices (from left to right): Metering and AF Start; Metering Start; and AE lock (* button is pressed). The default value is Metering and AF Start, which you want to uncouple. Select Metering Start instead, and press SET to confirm.

- 6. Set AF-ON button to activate autofocus. You’ll be returned to the Custom Controls menu. Scroll down to the next entry, AF-ON Button, and press SET. Select Metering and AF Start (if it’s not already selected; it’s the default value). Press SET to confirm.

- 7. Exit. Press the MENU button twice to exit (or just tap the shutter release button).

Use back-button focus. Henceforth, press the shutter release halfway to meter, and all the way to take a picture, and press the AF-ON button to activate autofocus.

Fine-Tuning the Autofocus of Your Lenses

The Canon EOS 90D has a feature called AF Microadjustment, which I hope you never need to use, because it is applied only when you find that a lens is not focusing properly. If the lens happens to focus a bit ahead or a bit behind the actual point of sharp focus, and it does that consistently, you can use the microadjustment feature to “calibrate” the lens’s focus.

Microadjustment may be needed because the autofocus mechanism in the floor of the mirror box has become slightly misaligned. In that case you’ll want to use the Adjust All By Same Amount option in the Custom Function II-16 screen. Or, an individual lens may be a little off-kilter, and you can use the separate Adjust By Lens option. I’ll describe both. Note that AF Microadjustment is theoretically required only for viewfinder shooting; autofocus in Live View and Movie mode use the sensor image to calculate focus and don’t rely on the mirror-box AF components.

Caution! Use this control, which allows you to tweak the point of focus of individual lenses, with care. Well-intentioned, but inaccurate adjustments can turn slight focus problems into major ones. I’ll cover this drastic correctional step in detail next.

Why is the focus “off” for some lenses in the first place? There are lots of factors, besides alignment of the AF mechanism itself, including the age of the lens (an older lens may focus slightly differently), temperature effects on certain types of glass, humidity, and tolerances built into a lens’s design that all add up to a slight misadjustment, even though the components themselves are, strictly speaking, within specs. A very slight variation in your lens’s mount can cause focus to vary slightly. With any luck (if you can call it that), a lens that doesn’t focus exactly right will at least be consistent. If a lens always focuses a bit behind the subject, the symptom is back focus. If it focuses in front of the subject, it’s called front focus.

You’re almost always better off sending your camera or lens into Canon to have them make it right. But that’s not always possible. Perhaps you need your system recalibrated right now, or you purchased a used lens that is long out of warranty. If you want to do it yourself, the first thing to do is determine whether your lens has a back-focus or front-focus problem.

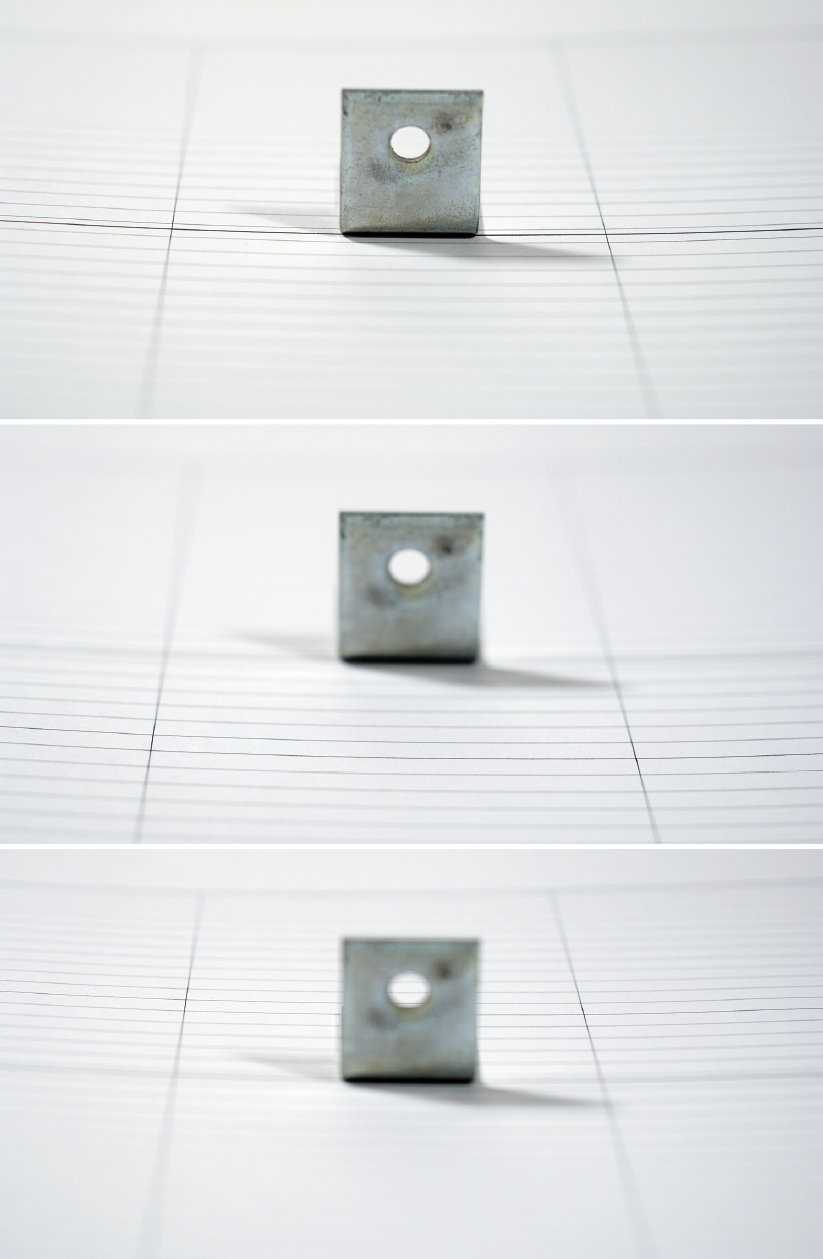

For a quick-and-dirty diagnosis (not a calibration; you’ll use a different target for that), lay down a piece of graph paper on a flat surface, and place an object on the line at the middle, which will represent the point of focus (we hope). Then, shoot the target at an angle using your lens’s widest aperture and the autofocus mode you want to test. Mount the camera on a tripod so you can get accurate, repeatable results.

If your camera/lens combination doesn’t suffer from front or back focus, the point of sharpest focus will be the center line of the chart, as you can see in Figure 5.12. If you do have a problem, one of the other lines will be sharply focused instead. Should you discover that your lens consistently front or back focuses, it needs to be recalibrated. Unfortunately, it’s only possible to calibrate a lens for a single focusing distance. So, if you use a lens (such as a macro lens) for close focusing, calibrate for that. If you use a lens primarily for middle distances, calibrate for that. Close-to-middle distances are most likely to cause focus problems, anyway, because as you get closer to infinity, small changes in focus are less likely to have an effect.

Figure 5.12 Correct focus (top), front focus (middle), and back focus (bottom).

Lens Tune-Up

The key tool you can use to fine-tune your lens is the AF Microadjustment entry, C.Fn II-16. You’ll find the process easier to understand if you first run through this quick overview of the menu options:

- 0: Disable. Deactivates autofocus microadjustment. You might want to use this if you’ve mounted a different copy of a lens you’ve registered for adjustment. For example, a photojournalist might make an adjustment for his or her personal lens, and then need to borrow a different copy of the exact same lens from a friend or a department’s equipment pool. The 90D can’t tell the two lenses apart, so it’s probably best to disable the microadjustment feature while using that “foreign” lens.

- 1: Adjust all by same amount. The same adjustment is applied to all your lenses. You’d use this if your camera, rather than just a lens or two, requires calibration. (In this case, I particularly recommend sending the camera back to Canon for repair.)

- 2: Adjust by lens. You can set an adjustment individually for up to 40 different lens combinations (lens+teleconverter combinations are registered separately). If you discover you don’t care for the calibrations you make in certain situations (say, it works better for the lens you have mounted at middle distances, but is less successful at correcting close-up focus errors), or, as described above, are using a different copy of the exact same lens, you can deactivate the feature as you require. Adjustment values range from –20 to +20.

Evaluate Current Focus

The first step is to capture a baseline image that represents how the lens you want to fine-tune autofocuses at a particular distance. You’ll often see advice for photographing a test chart with millimeter markings from an angle, and the suggestion that you autofocus on a point on the chart. Supposedly, the markings that actually are in focus will help you recalibrate your lens. The problem with this approach is that the information you get from photographing a test chart at an angle doesn’t actually tell you what to do to make a precise correction. So, your lens back focuses three millimeters behind the target area on the chart. So what? Does that mean you change the value –3 increments? Or –15 increments? Angled targets are a “shortcut” that don’t save you time.

Instead, you’ll want to photograph a target that represents what you’re actually trying to achieve: a plane of focus locked in by your lens that represents the actual plane of focus of your subject. For that, you’ll need a flat target, mounted precisely perpendicular to the sensor plane of the camera. Then, you can take a photo, see if the plane of focus is correct, and if not, dial in a bit of fine-tuning in the AF Microadjustment menu, and shoot again. Lather, rinse, and repeat until the target is sharply focused.

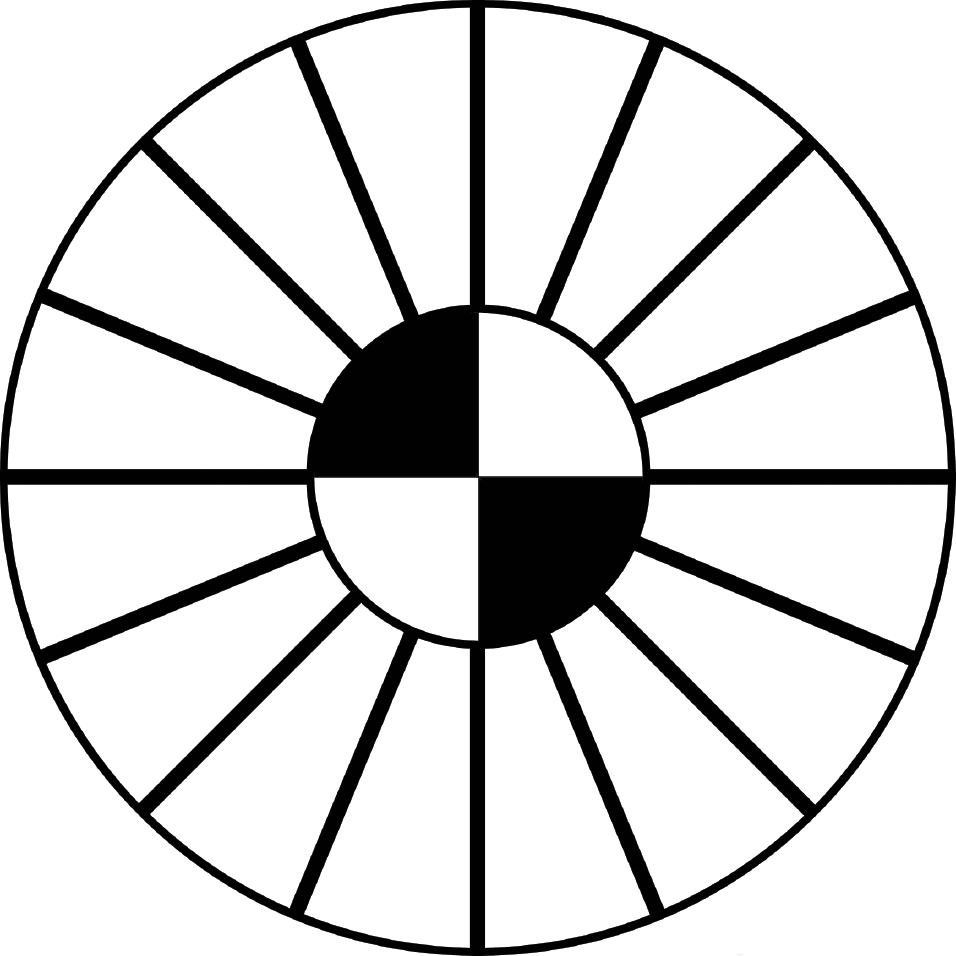

You can use the focus target shown in Figure 5.13, or you can use a chart of your own, as long as it has contrasty areas that will be easily seen by the autofocus system, and without very small details that are likely to confuse the AF. Download your own copy of my chart from www.dslrguides.com/FocusChart.pdf. (The URL is case sensitive.) Then print out a copy on the largest paper your printer can handle. (I don’t recommend just displaying the file on your monitor and focusing on that; it’s unlikely you’ll have the monitor screen lined up perfectly perpendicular to the camera sensor.)

© 2016 DSLRGuides.com

Figure 5.13 Use this focus test chart or create one of your own.

- 1. Position the camera. Place your camera on a sturdy tripod with a remote release attached, positioned at roughly eye-level at a distance from a wall that represents the distance you want to test for. Keep in mind that autofocus problems can be different at varying distances and lens focal lengths, and that you can enter only one correction value for a particular lens. So, choose a distance (close-up or mid-range) and zoom setting with your shooting habits in mind.

- 2. Set the autofocus mode. Choose the autofocus mode (One-Shot AF or AI Servo AF) you want to test. (Because AI Auto mode just alternates between the two, you don’t need to test that mode.)

- 3. Level the camera (in an ideal world). If the wall happens to be perfectly perpendicular, you can use a bubble level, plumb bob, or other device of your choice to ensure that the camera is level to match. Many tripods and tripod heads have bubble levels built in. Avoid using the center column if you can. When the camera is properly oriented, lock the legs and tripod head tightly.

- 4. Level the camera (in the real world). If your wall is not perfectly perpendicular, use this old trick. Tape a mirror to the wall, and then adjust the camera on the tripod so that when you look through the viewfinder at the mirror, you see directly into the reflection of the lens. Then, lock the tripod and remove the mirror.

- 5. Mount the test chart. Tape the test chart on the wall so it is centered in your camera’s viewfinder.

- 6. Photograph the test chart using AF. Allow the camera to autofocus, and take a test photo, using the remote release to avoid shaking or moving the camera.

- 7. Make an adjustment and rephotograph. Make a fine-tuning adjustment (described next) and photograph the target again.

- 8. Evaluate the image. If you have the camera connected to your computer with a USB cable or through a Wi-Fi connection, so much the better. You can view the image after it’s transferred to your computer. Otherwise, carefully open the camera card door and slip the memory card out and copy the images to your computer.

- 9. Evaluate focus. Which image is sharpest? That’s the setting you need to use for this lens. If your initial range doesn’t provide the correction you need, repeat the steps between –20 and +20 until you find the best fine-tuning.

Make Adjustments

Making the adjustments is simple. From the AF Microadjustment entry, C.Fn II-16, select AF Micro-adjustment, and choose from Adjust All By Same Amount, Adjust By Lens, or Disable.

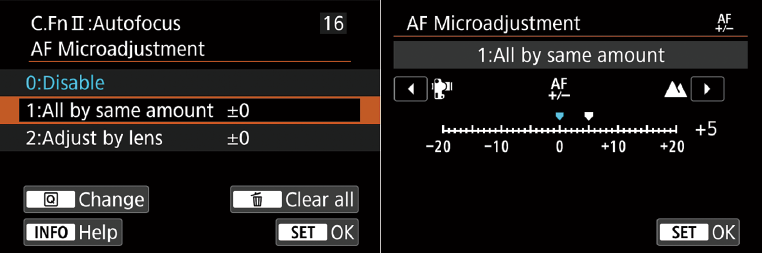

- Adjust All By Same Amount. Use this if all your lenses appear to front focus or back focus all the time, and consistently. Highlight the entry (see Figure 5.14, left) and press the SET button. You can clear current adjustment settings by pressing the Trash button. Or, press the Q button to produce a screen with a scale from –20 to +20. (See Figure 5.14, right.) Use the Quick Control Dial to choose a value, and press SET to confirm.

Figure 5.14 Choose All By Same Amount (left). Adjustments toward the left move the focus plane closer to the camera; adjustments to the right move it farther away (right).

Figure 5.15 Choose Adjust By Lens (left). For zoom lenses, adjust for telephoto and wide-angle settings, or both (right). Non-zoom lenses display only a single scale.

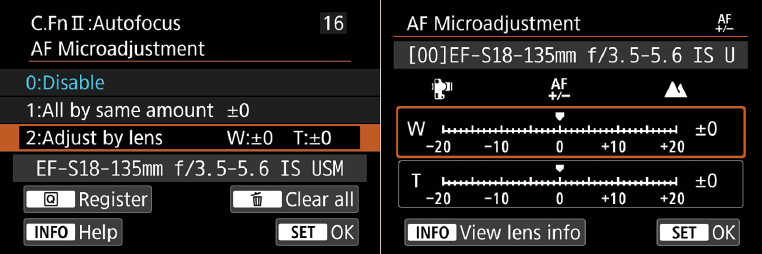

- Adjust By Lens. Follow these steps:

- 1. Highlight Adjust By Lens and press the Q button. (See Figure 5.15, left.) A screen like the one shown in Figure 5.15, right, will appear. For a prime lens, there will be only a single adjustment scale; for a zoom lens, there will be one scale for W (wide-angle) and one for T (telephoto) focal lengths.

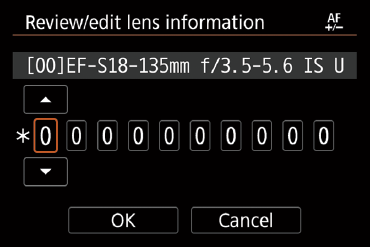

- 2. Press the INFO. button. The Review/Edit lens information screen appears. (See Figure 5.16.) It shows the name of the currently mounted lens and a 10-digit serial number (or 0000000000 if the number cannot be obtained). Note that while the 90D can differentiate among various lenses, it “sees” all copies of the exact same lens as identical. If you own two copies of the same 50mm f/1.4 lens, the identical adjustment will be applied to both.

Figure 5.16 Press the INFO. button to view information about the lens mounted on the camera.

- 3. If the serial number is obtained, you can select OK to move on to the next step. If you need to edit the serial number, you can use the QCD to highlight any digit, then press SET to edit that digit. Rotate the QCD to increase or decrease the value of the digit. Select OK when finished.

- 4. Select the scale and then rotate the QCD to adjust between –20 and +20 (no letters required). Moving the indicator to the right moves the focus point to the rear of the standard point of focus. Adjusting to the left moves the focus point to a position in front of the default focus point.

- 5. Press SET to confirm your changes. The 90D has enough memory to store values for 40 different lenses or lens+tele-extender combinations (handy!). If you want to register more than 40 lenses, select a lens with an adjustment that can be deleted, mount it on the camera, and reset its adjustment to 0. That will free up a slot for a different lens.

NOTEThe –20/+20 increments are not fixed values: they are based on the amount of depth-of-field available with the lens at its widest aperture. Canon states that each increment represents one-eighth of the available depth-of-field at the focal length being adjusted. That means that the increments are not only very fine but produce different amounts of adjustment based on whether you are tweaking a wide-angle or telephoto focal length.