[ 6 ]

Decision Making and Problem Solving: Enter Consciousness, Stage Left

most of the processes I’ve introduced so far, like attentional shifts and associating words with their meanings, occur automatically, even if they’re influenced by consciousness. In contrast, this chapter focuses on the very deliberate and conscious process of decision making and problem solving. Relative to other processes, this is the one that you’re the most aware of and in control of. Right now as you are reading this, you’re aware that you’re thinking about thinking and decision making.

In this chapter we will focus on how we, as decision makers, define where we are now and our goal state, and make decisions to get us closer to our desired goal. Designers rarely think in these terms, but I hope to change that.

What Is My Problem (Definition)?

When you’re problem solving and decision making, you have to answer a series of questions. The first one is, “What is my problem?” By this I mean “What is the problem you’re trying to solve?” Where are you now (current state), and where do you want to go (goal state)?

For example, consider Escape Room, an adventure game where you have to solve a series of riddles as quickly as possible to get out of a room (Figure 6-1). While unlocking the door may be your ultimate goal, there are subgoals you’ll need to accomplish before that (e.g., finding the key) in order to get to your end goal. For example, you may need to open a locked glass cabinet that appears to hold the key, find clues about how to unlock the cabinet, etc. (I’m making these up; no spoiler alerts here!).

Figure 6-1

People searching for clues in an escape room

Chess is another example of building subgoals within larger goals. Your ultimate goal is to checkmate the opponent’s king. As the game progresses, however, you’ll need to create subgoals to help you reach your ultimate goal. Your opponent’s king is protected by his queen and a bishop, so a subgoal (to the ultimate goal of putting the opponent’s king into checkmate) could be eliminating the bishop. To do this, you may want to use your own bishop, which then necessitates another subgoal of moving a pawn out of the way to free up that piece. Your opponent’s moves will also trigger new subgoals for you—such as getting your queen out of a dangerous spot, or transforming a pawn by moving it across the board. In each of these instances, subgoals are necessary to reach the desired end goal.

How Might Problems Be Framed Differently?

Remember when we talked about experts and novices in the last chapter, and the unique words each group uses? When it comes to decision making, experts and novices are often thinking about (or “framing”) the problem very differently, too.

Let’s consider buying a house, for example. The novice home buyer might be thinking, “What amount of money do we need to offer for the owner to accept our bid?” Experts, however, might be thinking about several more things: Can this buyer qualify for a loan? What is their credit score? Have they had any prior issues with credit? Do the buyers have the cash needed for a down payment? Will this house pass an inspection? What are the likely repairs that will need to be made before the buyers might accept the deal? Is this owner motivated to sell? Is the title of the property free and clear of any liens or other disputes?

So while the novice home buyer might frame the problem as just one challenge (convincing the buyer to sell their house at a specific price), the expert is thinking about many other things as well (e.g., a “clean” title, building inspection, credit scores, seller motivations, etc.). From these different perspectives, the problem definition is very different, and the decisions the two groups make and actions they might take will also likely be very different.

In many cases, novices (e.g., first-time home buyers or car buyers) don’t define the problem that they really need to solve because they don’t understand all the complexities and decisions they need to make. Their knowledge of the problem might be overly simplistic relative to reality.

This is why the first thing we need to understand as product designers is how our customers define the problem they are solving. We need to meet them there, and, over time, help to redirect them to what their actual (and likely more complex) problem is and help them along the way. This is known as redefining the problem space.

|

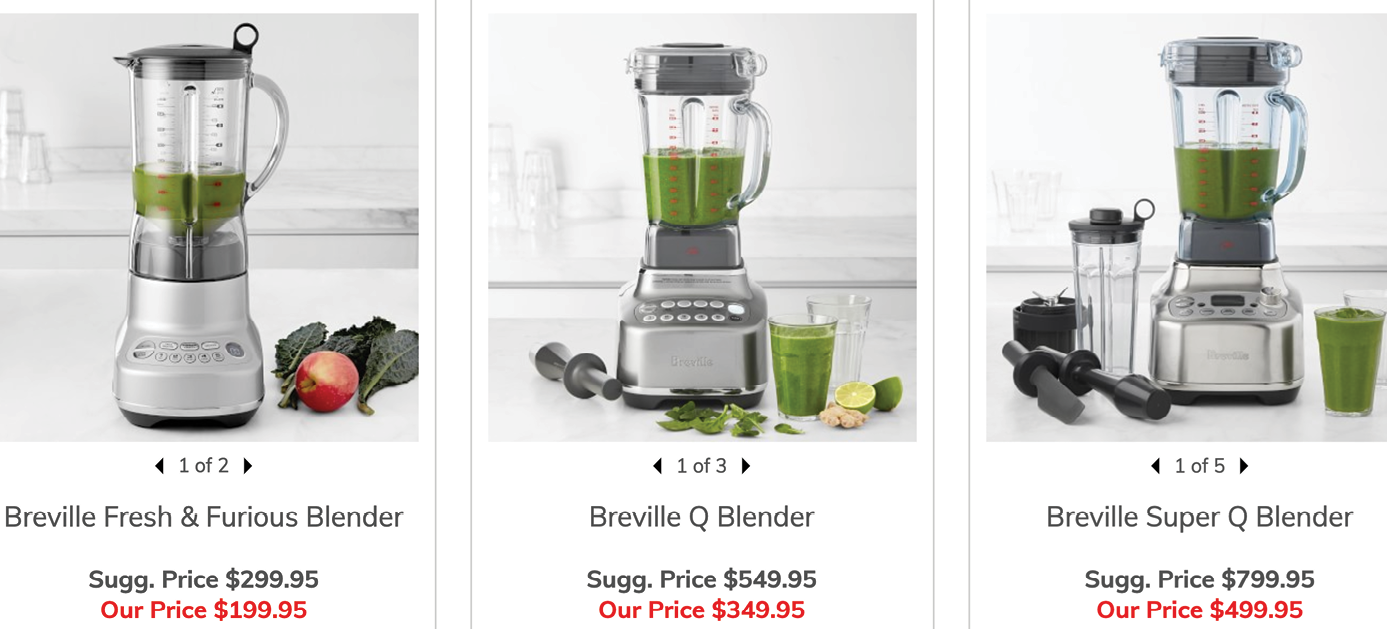

[ side note ] Framing and defining the problem are very different, but both apply to this section. To boost a product’s online sales, you may place it in between two higher- and lower-priced items. You will have successfully framed your product’s pricing (see Figure 6-2). Instead of viewing it on its own, as a $349 blender, users will now see it as a “middle-of-the-road” option, not too cheap but not $499, either. As a consumer, be aware of how the art of framing a price can influence your decision-making skills. And as a designer, be aware of the power of framing. |

Figure 6-2

Mutilated Checkerboard Problem

A helpful example of redefining a problem space comes from the so-called “mutilated checkerboard problem,” as defined by cognitive psychologists Craig Kaplan and Herbert Simon. The basic premise is this: imagine you have a checkerboard. (If you’re in the US, you’re probably imagining intermittent red and black squares; if in the UK, you might call this a chessboard, with white and black squares. Either version works in this example.) It’s a normal checkerboard, except for the fact that you’ve removed the two opposite black corner squares from the board, leaving you with 62 squares instead of 64. You also have a bunch of dominoes, which cover two squares each (see Figure 6-3).

Figure 6-3

Mutilated checkerboard

Your challenge: Arrange 31 dominoes on the checkerboard such that each domino lies across its own pair of red/black squares (no diagonals).

Moving around the problem space: When you challenge someone with this problem, they inevitably start putting dominoes onto the checkerboard to solve it. Near the end of that process, they inevitably get stuck and try repeating the process. (If you are able to solve the problem without breaking the dominoes, be sure to send me your solution!)

The problem definition challenge: The problem as posed is unsolvable. If every domino has to go on one red and one black square, and there are no longer an equal number of red and black squares on the board (since we removed two black squares and no red squares), the problem can’t be solved. To the novice, the definition of the problem, and the way to move around in the problem space, is to lay out all the dominoes and figure it out. Each time they put down a domino they believe they are getting closer to the end goal. They’ve likely calculated that since there are now 62 squares, and 31 dominoes, and each domino covers 2 spaces, the math works. An expert, however, instantly knows that you need equal numbers of red and black squares to make this work, and won’t bother to try to lay dominoes on the checkerboard.

Finding the Yellow Brick Road to Problem Resolution

I’ve mentioned moving around in the problem space from your starting state to the goal state. Let’s look at that component more closely.

First, it’s really important that as product or service designers, we make no assumptions about what the problem space looks like for our customers. As experts in the problem space, we know all the possible moves around that space that can be taken, and it often seems obvious what decisions need to be made and what jobs need to be done. That same problem may look very different to our (less expert) customers.

In games like chess, it’s clear to all parties involved what their possible moves are, if not all the consequences of their moves. In other realms, like getting health care, the steps aren’t always so clear. As designers of these processes, we need to learn what our audiences see as their “yellow brick road.” What do they think the path is that will take them from their beginning state to their goal state? What do they see as the critical decisions to make? The road they’re envisioning may be very different from what an expert would envision, or what is even possible. But once we understand their perspective, we can work to create a product or service that serves to gradually morph their novice mental models into a more educated one so that they make better decisions and understand what might be coming next.

When You Get Stuck En Route: Subgoals

We’ve talked about problem definition for our target audiences, but what about when they get stuck? How do they get around the things that may block them (“blockers”)? Many users see their end goal, but what they don’t see, and what we product and service designers can help them see, are the subgoals they must have—and the steps, options, and possibilities for solving those subgoals.

One way to get around blockers is through creating subgoals, like those we discussed in the Escape Room example. You realize that you need a certain key to unlock the door. You can see that the key is in a glass box with a padlock on it. Your new subgoal is opening the padlock (to unlock the cabinet to get the key to unlock the door).

We can also think of these subgoals in terms of questions the user needs to answer. To lease a car, the customer will need to answer many subquestions (How old are you?, How is your credit?, Can you afford the monthly payments?, Can you get insurance?) before the ultimate question (Can I lease this car?) can be answered. In service design, we want to address all of these potential subgoals and subquestions for our user so they feel prepared for what they’re going to get from us. It’s important that we address these microquestions in a logical progression.

Ultimately, you as a product or service designer need to understand:

- The actual steps to solve a problem or make a decision

- What your audience thinks the problem or decision is and how to solve it

- The subgoals your audience might create to get around “blockers”

- How to help the target audience shift their thinking from that of a novice to that of an expert in the field (changing their view of the problem space and subgoals) to be more successful

Now that we have considered decision making and problem solving from a logical, rational, “Does this make sense?” level, in the next chapter we’ll consider how emotions and decision making are inherently intertwined.

Further Reading

Ariely, D. (2008). Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces that Shape Our Decisions. New York: HarperCollins.

Pink, D. H. (2009). Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us. New York: Riverhead Books.

Thaler, R. & Sunstein, C. (2008). Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth and Happiness. New York: Penguin Books.