[ 14 ]

Emotion: The Unspoken Reality

We might know what our customers are trying to do on a logical level (e.g., buy a car), but what are they trying to accomplish on a deeper level? What emotions do those goals or fears of failure illicit? Based on those emotions, how “Spock-like,” or analytical, will a person be in their decision making?

In this chapter, we return to the last of our Six Minds: emotion (Figure 14-1). As we discuss emotion, we’ll consider these questions:

- What immediate emotions are our users experiencing as they interact with our products or services?

- Which comments pertain to who this person is (i.e., their self-concept)?

- What are they trying to accomplish in life?

- What are they most afraid of having go wrong? Why?

- Who are our customers on a deeper level?

- What will make them feel accomplished?

Figure 14-1

Emotion often forms deep within the cortex and lower systems

Live a Little (Finding Reality, Essence)

When talking about emotion, I want you to be thinking about it on three planes:

- Appeal

What will draw customers in immediately? An exclusive offer? Some feature that ticks one of their microdecision-making boxes? During a customer experience, what specific events or stimuli (e.g., encountering a password prompt or using a search function) are associated with emotional reactions?

- Enhance

What will enhance customers’ lives and provide meaningful value over the next six months, and beyond?

- Awaken

Over time, what will help awaken your customers’ deepest goals and wishes (and support them in accomplishing those goals)? What are some of the underlying emotions they have about who they are and what they’re trying to become (e.g., a good father, a millionaire, a steady worker)? What are they afraid of?

Though quite different, all of these forms of emotion are extremely important to consider in our overall experience design. We want to know what our consumers are thinking about themselves at a deep level, what might make them feel accomplished in society, and what their biggest fears are. Our challenge is then to design products for both the immediate emotional responses as well as those deep-seated goals and fears.

|

[ Side note ] While it may be tempting to focus on the perks of our products, we have to go back to Daniel Kahneman, who tells us that humans dislike losses more than we like gains. As such, it’s extremely important to consider fear. There could be short-term fears, like not receiving a product in the mail on time, but there are also longer-term fears, like not being successful. By addressing not only what people are ultimately striving for but also what they are ultimately afraid of, we can provide ultimate value. |

Case Study: Credit Card Theft

Challenge: In talking about identification and identity theft on behalf of a financial institution, we met with a group of people whose identities had been stolen. For them, it was highly emotional to remember trying to buy the house of their dreams and being rejected because someone else had fraudulently taken out another mortgage using their identity. The house was tied to much deeper underlying notions, like their “forever home” where they wanted to grow old and raise kids, as well as the negative feelings of unfair rejection they had to experience. All in all, they had a lot of fear and mistrust of the process and of financial institutions due to their past experiences.

Outcome: In each of these cases, whether it was being denied a mortgage or having a credit card rejected at Staples, these consumers had deeply emotional associations with the idea of credit. For them, it was essential that we find ways to help shape not only their unique decision-making processes, but also their perceptions and mistrust of financial institutions on the whole. In this case we found that considering the products and services in such a way that they weren’t directly tied to financial institutions helped to distance them from the strong emotional experiences that could easily be elicited.

Analyzing Dreams (Goals, Life Stages, Fears)

The following case study is just one example of how dreams, goals, and fears can change by one’s stage in life.

Case Study: Psychographic Profile

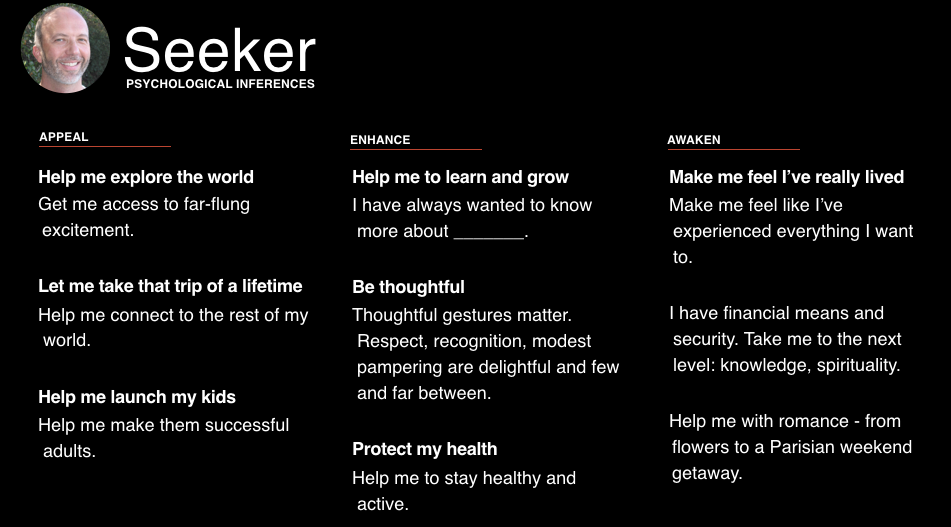

Challenge: In my line of work, sometimes we create “psychographic profiles” to segment (and better market to) groups of consumers. One artificial but representative example, is shown in Figure 14-2. It relates to the questions we asked on behalf of a credit card company, which I mentioned back in Chapter 6. In these interviews, we went from the short-term emotions to the longer-term emotions to what people were ultimately trying to accomplish. These types of interviews can be like therapy (for the participants, not us).

Figure 14-2

Example of a persona focused on what appeals to, enhances, and awakens a customer

Outcome: As you can see in the first column, the things that appealed to this group of consumers—older, possibly retired adults who might have grown children—were things they could do with their newly discovered free time. Things like taking that trip to Australia, or further supporting their kids in early adulthood by helping them launch their careers, buy houses, etc.

Over the course of the contextual interviews, we were able to go a bit further than the short-term goals (e.g., a trip to Australia) and get to what they were seeking to enhance. Things like learning to play the piano, receiving great service and respect when they stay at hotels, or maintaining/improving their health.

Then, going even longer term, we got to the notion of what they wanted to awaken in their lives. For many in this focus group, they were thinking beyond material success and were seeking things like knowledge, spirituality, service, or leaving a lasting impact on their community—the next level of fulfillment, awakening their deepest passions. As well as desire, we also observed a level of fear at not having these passions fulfilled. These were all emotions we wanted to address in our products and services for this group.

Getting the Zeitgeist (Person versus Persona-Specific)

In considering emotion, we’re also taking into account the distinct personalities of our end audience, the deeper undercurrent of who they are, and who it is they’re trying to become.

Case Study: Adventure Race

Challenge: It’s not every day you get to join in on a mud-filled adventure race for work. In the one pictured in Figure 14-3, many of the runners were members of the police force or former military—all very serious athletes; as you can imagine. Our client, however, saw an opportunity to attract families and “average Joes” too.

Outcome: In watching people participate in one of these races (truly engaging in contextual inquiry, covered in mud from head to toe, I might add), my team and I observed that the runners all had this amazing sense of accomplishment at the end of the race, as well as during the race. It was clear that they were each digging really deep into their psyche to push through some obstacle (be it running through freezing-cold water or crawling under barbed wire) to finish the race, and that these were metaphors for other obstacles in their lives that they might also overcome.

Figure 14-3

Passion at a Spartan Obstacle Race

By observing this emotional content, we saw that this was something we could harness not only for the dedicated race types, but ordinary people as well (I don’t mean that in a degrading way; even this humble psychologist ran the race, so there’s hope for everyone!). In our product and service design efforts going forward, we harnessed the emotional content like running for a cause (as was the case with a group of cancer survivors or ex-military who were overcoming PTSD), running with a friend for accountability, giving somebody a helping hand, or signing up with others from your family, neighborhood, or gym. We knew these deeper emotions would be crucial to people deciding to sign up and invite friends.

A Crime of Passion (In the Moment)

Remember the concept of satisficing? It’s somewhere between satisfactory and sufficing. Satisficing is all about emotion, and defaulting to the easiest or most obvious solution when we’re overwhelmed. There are many ways we do this, and our interactions with digital interfaces are no exception.

Maybe a web page is too busy, so we satisfice by leaving the page and going to a tried-and-true favorite. Maybe we’re presented with so many options for a product (or candidates on the ballot for our state’s primary elections?) that we just select the one that’s displayed the most prominently, not taking specifications into consideration. Maybe we buy something out of our price range simply because we’re feeling stressed out and don’t have time to keep searching. You get the idea.

Case Study: Mad Men (and Women)

Challenge: Let me tell you a story about a group of young ad executives with whom we did contextual inquiry. Their first job out of college was with a prestigious ad agency in downtown New York City. They thought it was all very cool and were excited about their career possibilities. Often, they were put in charge of buying a lot of ads for a major client, and they literally were tasked with spending $10 million on ads in one day. In observing this group of young ad-men and – women, we saw emotions were running high. They were fearful because this task—picking which ads to run and on which stations—if done incorrectly, could end not only their careers, but also the “big city ad executive” lifestyles and personas they had cultivated for themselves. Making one wrong click would end their whole dream and send them packing in shame (or so they believed). There was an analytics tool in place for this group of ad buyers, but because they were so nervous, they would default to old habits (satisfice) and simply wouldn’t trust the automated system (even if it outperformed their own performance).

Outcome: We tweaked the analytics tool to show all the ad campaign stats the buyers would need at a glance. We made them very simple to understand and used visual attributes like bar graphs and colors to grab their attention. With so many emotions weighing in on their decisions, we wanted to make sure this tool made it clear what needed to be done next.

Real-World Examples

Let’s take a look at the sticky notes relevant to emotion (Figures 14-4 through 14-7):

“Loves that the product reviews are sorted by popularity.”

Comments that use words like “love” or “hate” shouldn’t necessarily be grouped into emotion, since their meaning always depends on context. This comment is talking about a specific design feature, so you could consider vision, wayfinding, or even memory if it’s meeting an expectation the user had. I’m still a bit torn, but I think the emotion of delight could be the strongest factor in this case.

Figure 14-4

Research observation: emotional terms do not always suggest an emotional source to response

“Wants his clothes to hint at his position (Senior Vice President).”

The comment we just looked at related to an immediate emotion tied to a specific stimulus. This one, however, exemplifies the deeper type of emotion I’ve been talking about (albeit perhaps with more possibility for nobility). Sure, you could argue it’s more of a surface-level comment—that this person is merely browsing for a certain type of clothing. But I would argue it speaks to a deep-seated desire to display a certain persona or image, and be perceived by others in that light. I think it encompasses a desire to look powerful, be treated a certain way, drive a certain type of car—or whatever this person envisions as representing “success.”

Figure 14-5

Research observation: hints at deeper motivations for decision

“Says ‘reviews are a scam, the store makes them up. I don’t trust them!’”

This one reads like pure emotion to me. Credibility and trust when it comes to ecommerce sites seem to be big hurdles for this user. What are some ways to present reviews such that these fears would be allayed?

Figure 14-6

Research observation: strong emotional response could be caused by something outside the product

|

[ Side Note ] Remember to take your users’ feedback in totality. In addition to this comment about reviews, this customer also remarked that he was afraid of “getting burned again” and that he wanted a way to compare products the way Consumer Reports does. Taken in totality, we can surmise that this person might have issues working up trust for any ecommerce system. With feedback like this, we want to think about what we could do to make our site trustworthy for our more nervous customers. |

“Afraid she might buy something by accident.”

This comment doesn’t include anything specific about interaction issues leading to this fear of accidentally buying something, so I would label it as an immediate emotional consideration, rather than anything more deep-seated.

Figure 14-7

Research observation: straightforward emotional comment

Concrete Recommendations

- Build up a set of questions throughout the interview that systematically go from the innocuous to the most meaningful (e.g., What credit cards are in your wallet? What do you like to do on the weekends? What makes you happiest? What are your goals this year? What would make you a success? What are you most fearful about that would stop you from getting there?).

- Determine how the customer’s goals in this case (e.g., shopping for clothes) fit into the larger picture of their life (e.g., excited to find someone to marry, want to feel young again, want to feel professional and be taken seriously).

- When building a persona, ensure that life stage and major fears are captured (e.g., older and fearful of having to search for a new job). Fears are powerful drivers away from logic.

- Estimate how much is on the line with the decision the customers are making (picking the right gum won’t get you fired, but getting the analysis wrong for the election will).